Transparency as a Trust Catalyst: How Self-Disclosure Strategies Reshape Consumer Perceptions of Unhealthy Food Brands on Digital Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

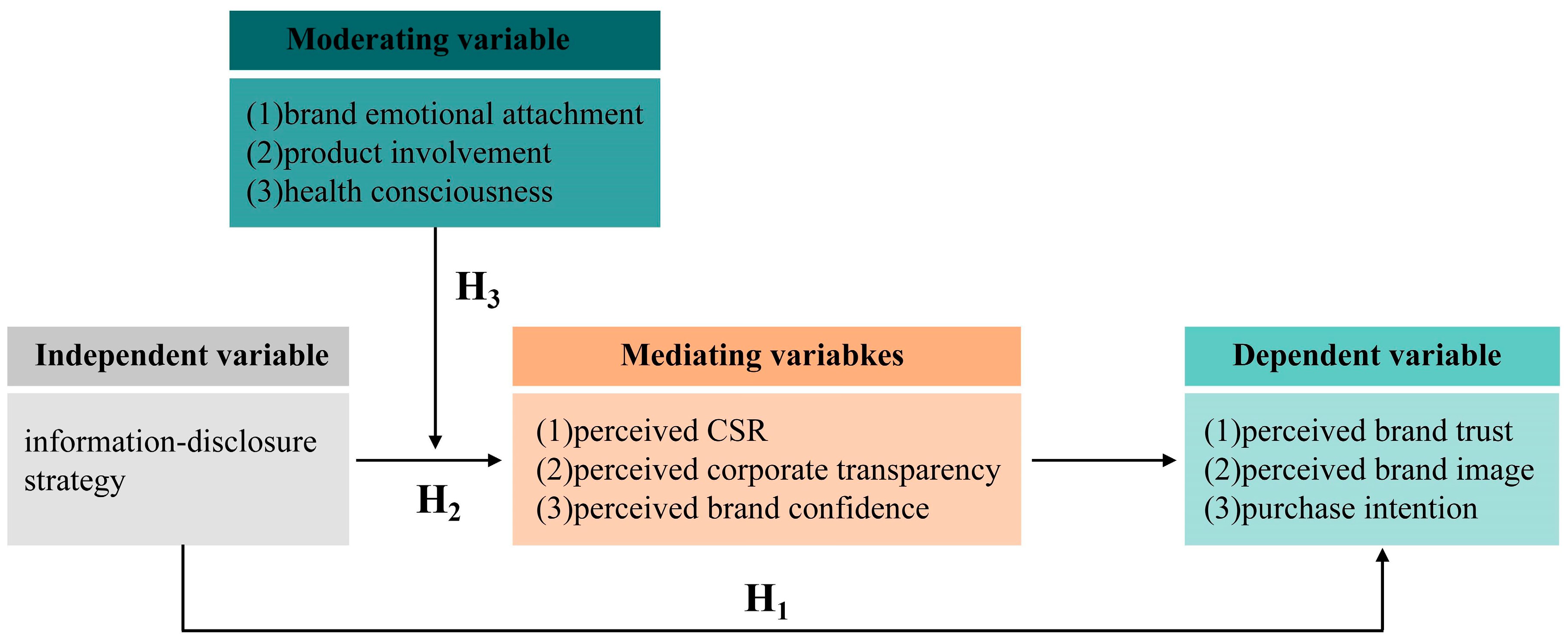

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Digital Marketing and Consumer Behavior

2.2. Transparent Communication, Information Asymmetry, and Signaling Theory

2.3. Proactive Negative Disclosure (Self-Disclosure) in Marketing

2.4. Attribution Theory and Consumer Psychology

2.5. Hypothesis Development

3. Study 1: Foundational Effects of Disclosure Strategies

3.1. Sample and Methods

3.1.1. Participants in Study 1

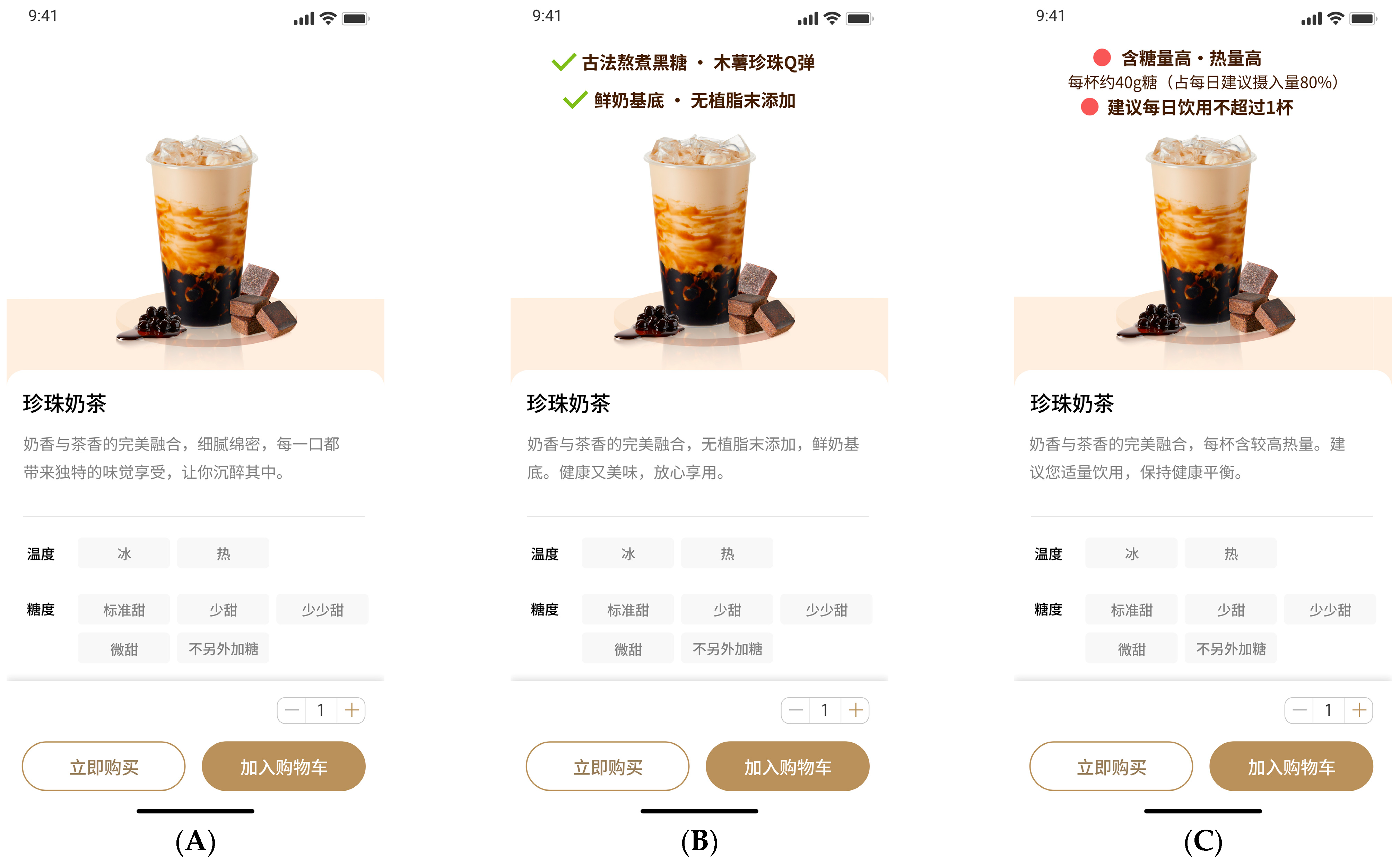

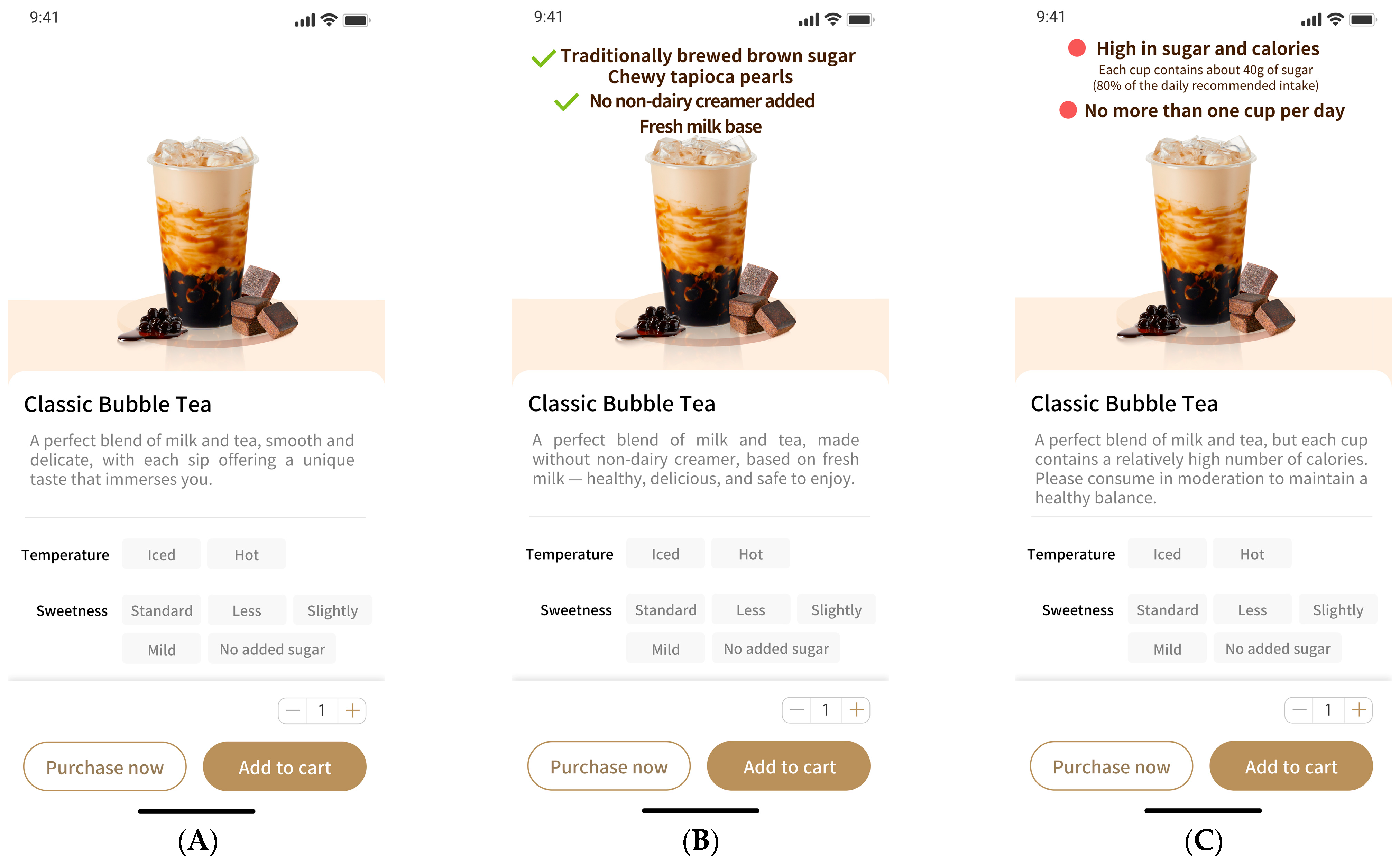

3.1.2. Experimental Design and Materials

- (1)

- Control group (no special disclosure) described the product neutrally as “a perfect blend of milk and tea flavors, delicate and creamy, offering a unique taste experience”, without health-related disclosures.

- (2)

- Self-promotion group (highlighting positive attributes) emphasized “traditionally cooked brown sugar with chewy tapioca pearls” and “fresh milk, no creamer added”, accompanied by the promotional statement, “A perfect blend of milk and tea flavors, fresh milk-based, healthy, delicious, and reassuring”.

- (3)

- Self-disclosure group (transparently disclosing negative attributes) clearly labeled “high sugar and calories”, with guidance recommending “limit to one cup per day”, and the following explanatory note: “A perfect blend of milk and tea flavors, containing higher calories. Enjoy in moderation to maintain a healthy balance”.

3.1.3. Procedure

3.1.4. Measures

- (1)

- Brand Trust

- (2)

- Brand Image

- (3)

- Purchase Intention

- (4)

- Manipulation Check

3.2. Results of Study 1

3.2.1. Manipulation Check of Study 1

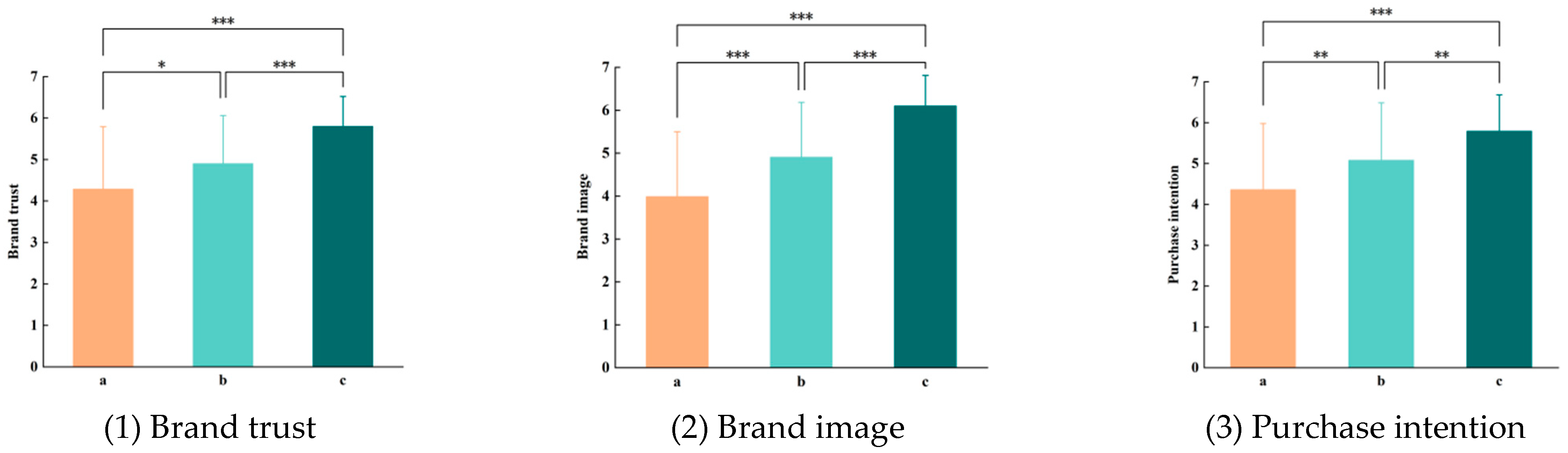

3.2.2. Main Effects Test

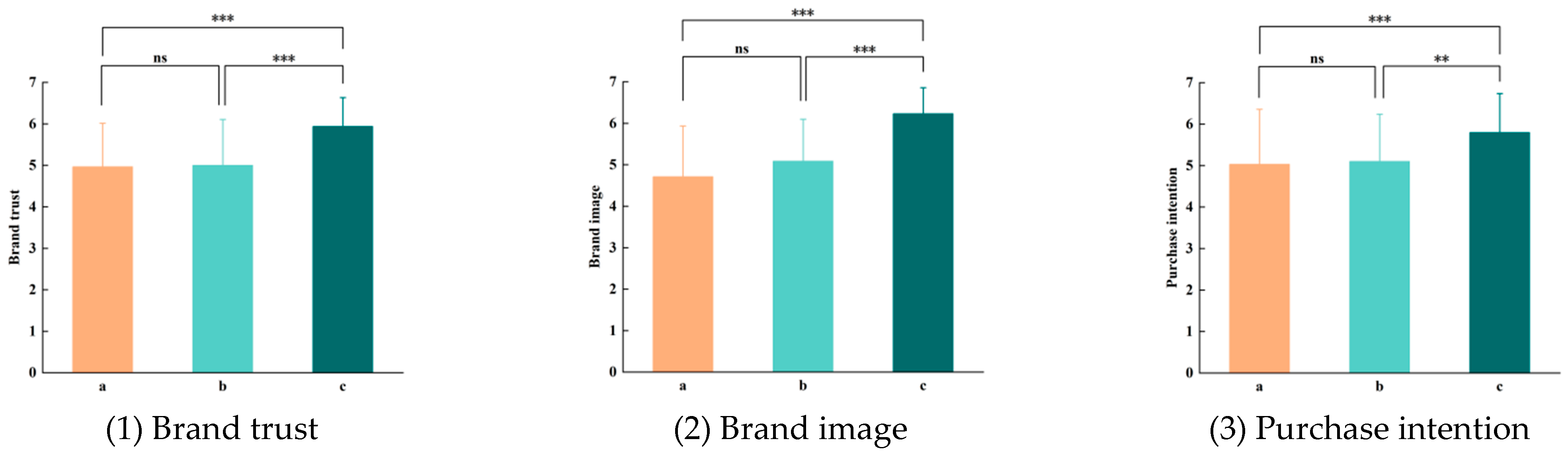

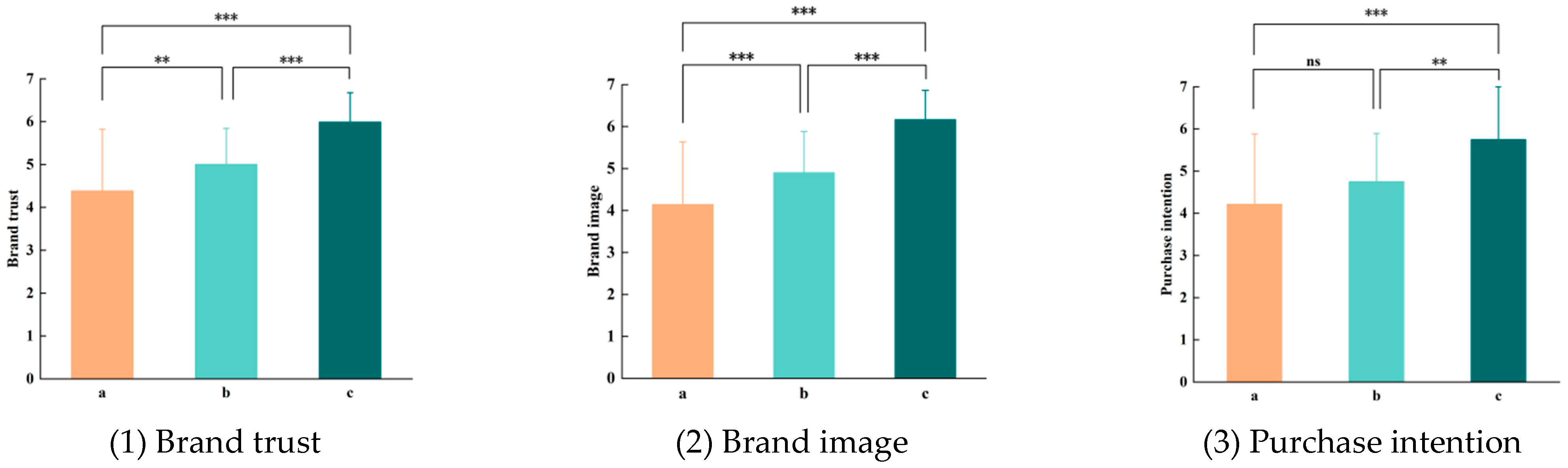

- (1)

- Brand Trust

- (2)

- Brand Image

- (3)

- Purchase Intention

3.3. Discussion of Study 1

4. Study 2: Unpacking the Trust-Building Mechanisms

4.1. Research Objective of Study 2

4.2. Participants in Study 2

4.3. Research Design and Experimental Materials

4.3.1. Research Design

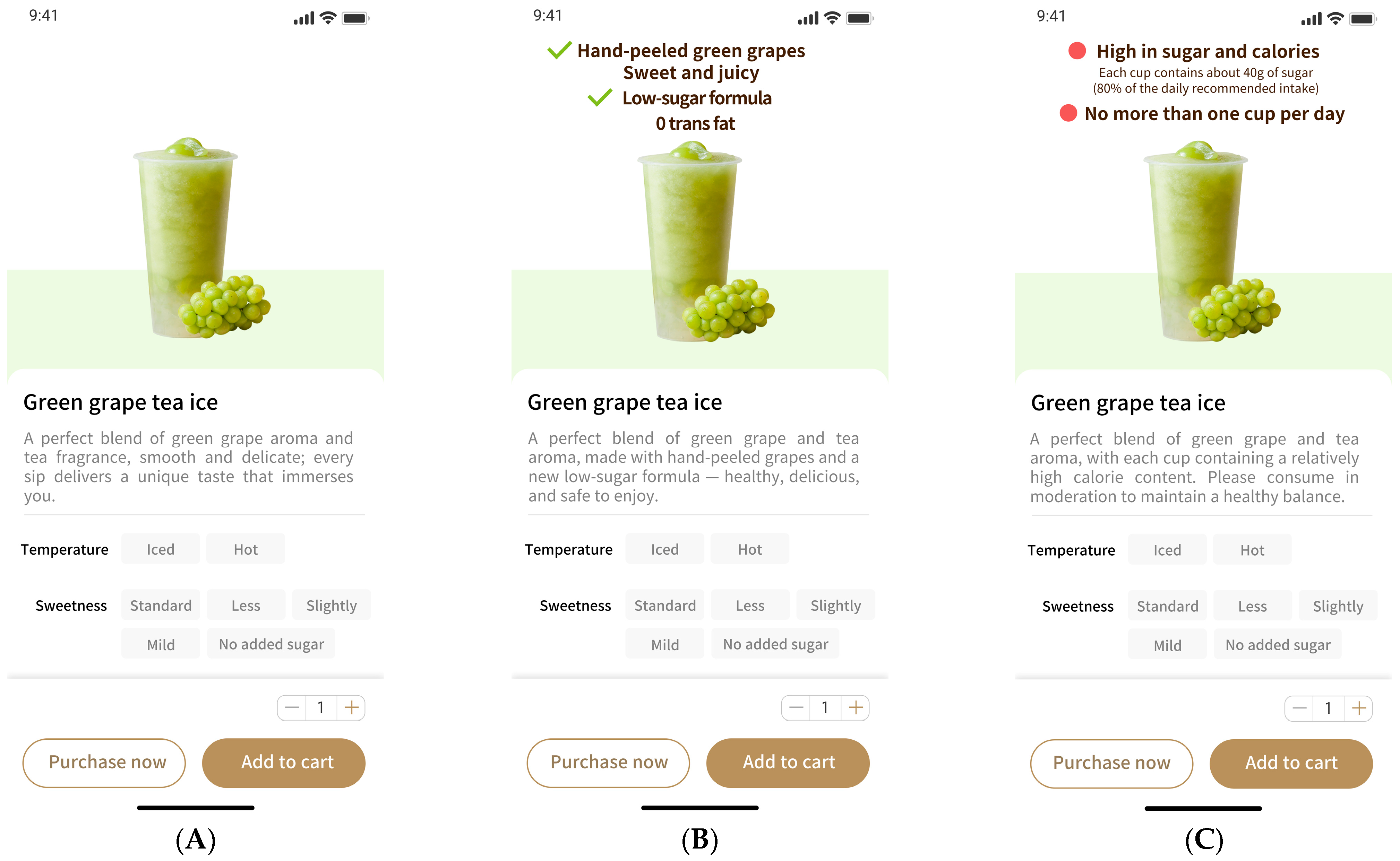

4.3.2. Stimuli and Scenario Setting

- (1)

- Control group (no health information disclosure): General description provided: “A perfect blend of grape and tea flavors, delicate and creamy, offering a unique taste experience”, without mention of any health-related attributes.

- (2)

- Self-promotion group (highlighting positive health attributes): Labels emphasized “hand-peeled grapes, juicy sweetness”, and “low-sugar recipe, zero trans-fat”, with promotional text stating “A perfect blend of grape and tea flavors, hand-peeled grapes, all-new low-sugar recipe. Healthy, delicious, and reassuring”.

- (3)

- Self-disclosure group (explicit negative health disclosure): Labels clearly indicated “High sugar and calories”, with recommendations to “Limit to one cup per day”, accompanied by explanatory text: “A perfect blend of grape and tea flavors, containing higher calories. Enjoy in moderation to maintain a healthy balance”.

4.4. Procedure and Operational Flow

- (1)

- (2)

- Perceived transparency based on Schnackenberg et al. (2016) [70], assessing openness, clarity, and authenticity in brand information disclosure. Example item: “The brand’s product disclosure makes me feel it is honest and trustworthy”. Scale reliability was high (Cronbach’s α > 0.85).

- (3)

- Brand confidence modified from Erdem et al. (1998) [71] to evaluate overall consumer confidence in brand quality and reputation. Example item: “I believe this brand consistently offers reliable quality”, rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Pretesting confirmed strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

4.5. Data Analysis and Results

4.5.1. Manipulation Check of Study 2

4.5.2. Main Effects Analysis in Study 2

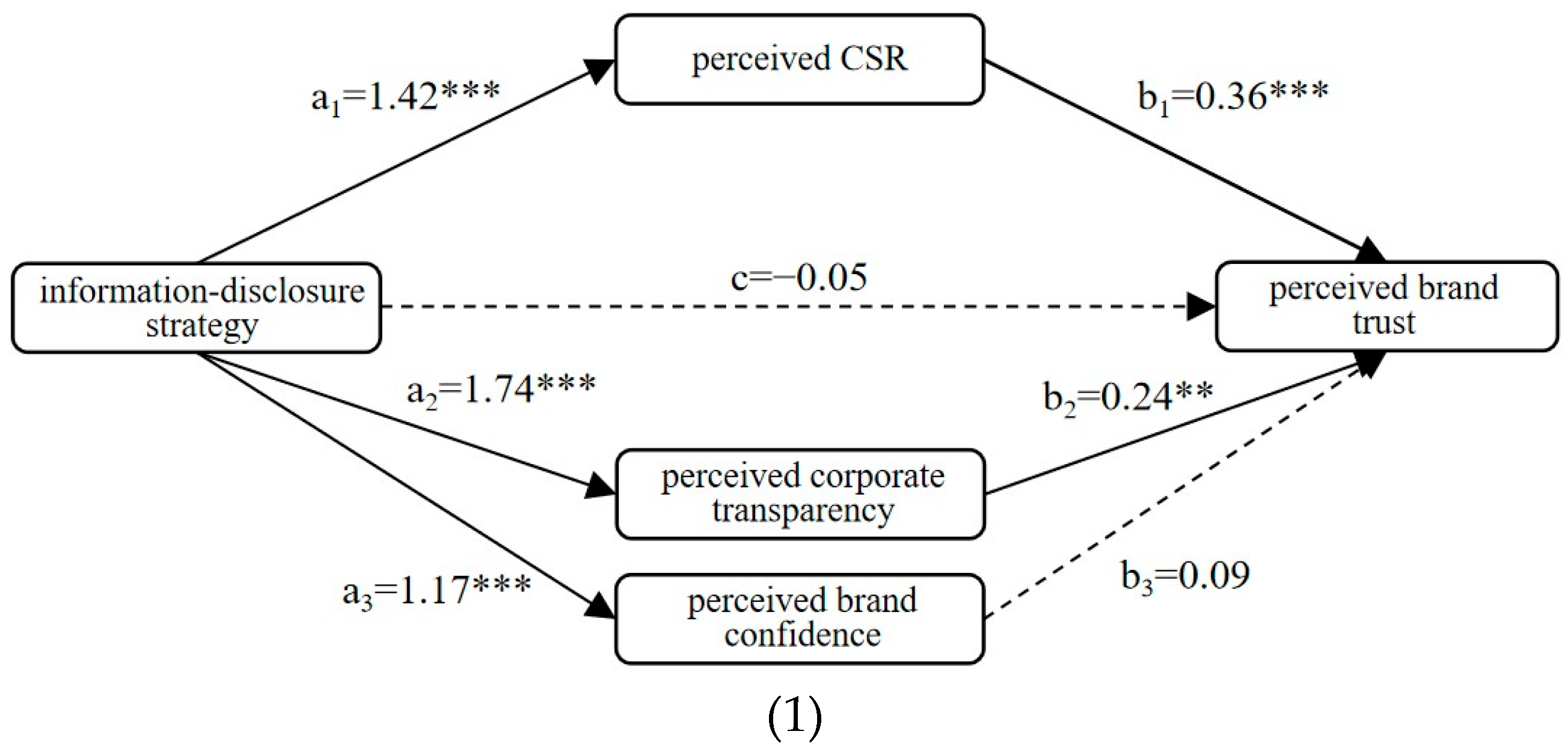

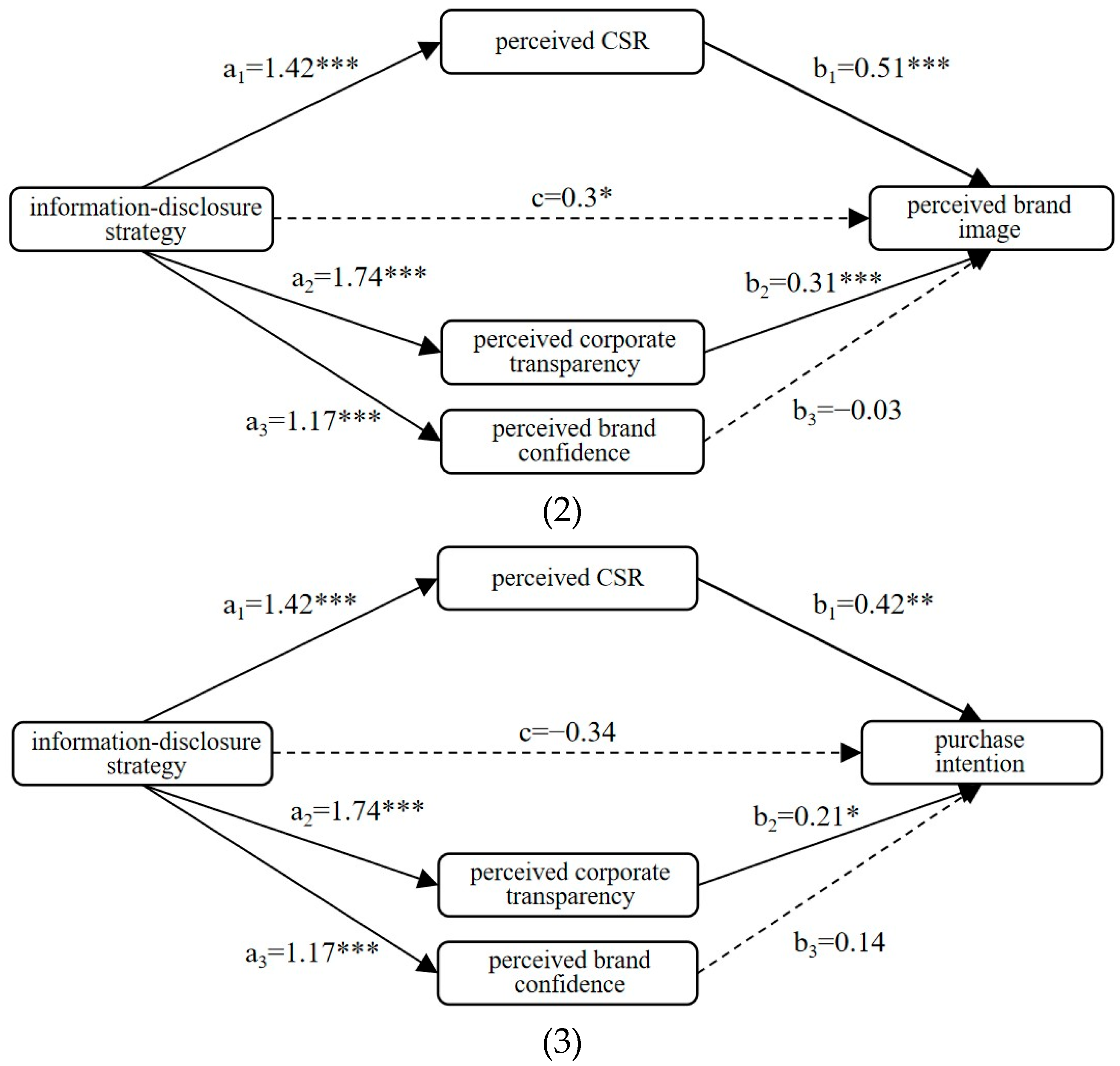

4.5.3. Mediation Analysis

4.6. Discussion of Study 2

5. Study 3: Consumer Attachment and Involvement as Boundary Conditions

5.1. Research Objective of Study 3

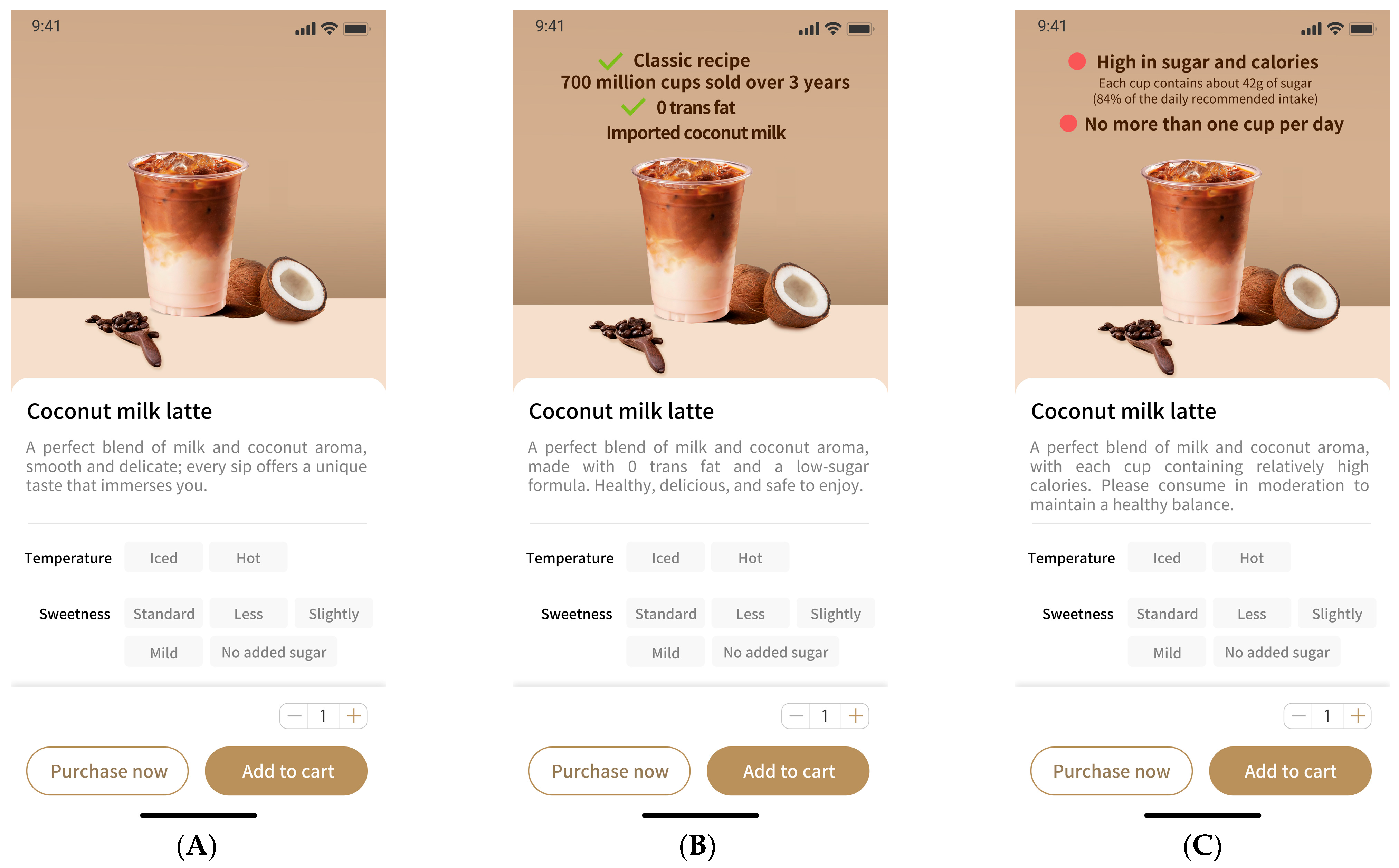

5.2. Research Design and Procedures

- (1)

- Control group (no additional health disclosure) had a basic flavor description provided—”A perfect blend of milk and coconut flavors, delicate and creamy, offering a unique taste experience”, without mentioning health-related attributes.

- (2)

- Self-promotion group (highlighting positive attributes) labels emphasized “classic Recipe—over 700 million cups sold in 3 years”, “zero trans-fat”, “imported coconut milk”, with the promotional statement ”A perfect blend of milk and coconut flavors, zero trans-fat, low-sugar recipe. Healthy, delicious, and reassuring”.

- (3)

- Self-disclosure group (explicit negative disclosure) labels clearly stated “high sugar and calories”, with the advice to “limit to one cup per day”, accompanied by the explanatory statement ”A perfect blend of milk and coconut flavors, containing higher calories. Enjoy in moderation to maintain a healthy balance”.

5.3. Results of Study 3

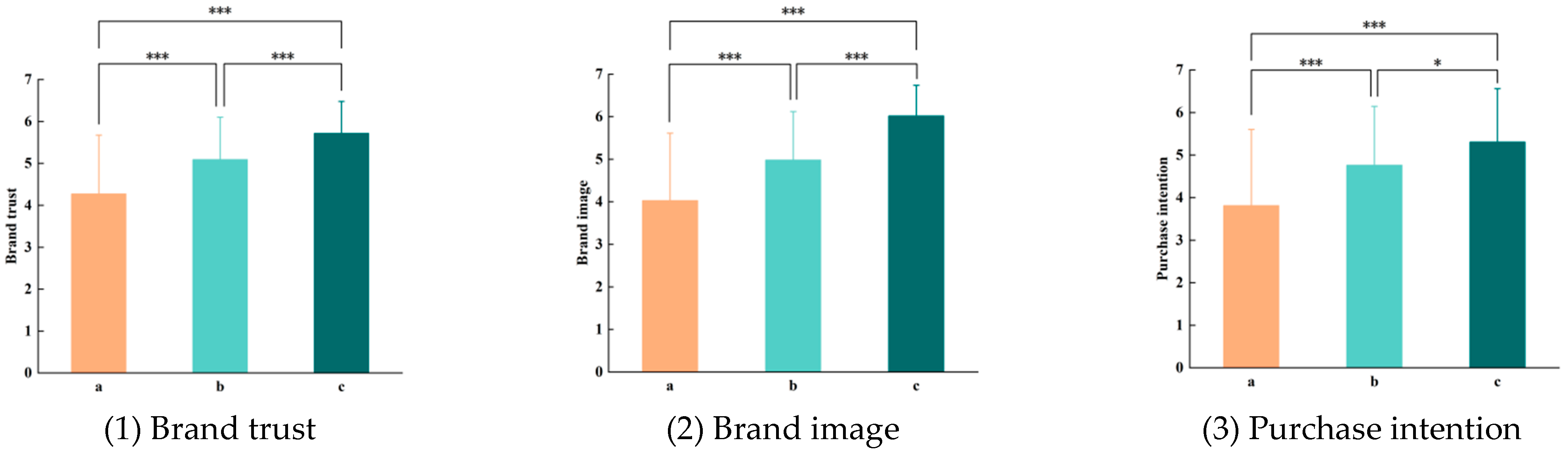

5.3.1. Main Effects Analysis in Study 3

- (1)

- Brand Trust

- (2)

- Brand Image

- (3)

- Purchase Intention

5.3.2. Test of Moderated Mediation Effects

- (1)

- The Moderating Role of Product Involvement

- (2)

- The Moderating Role of Emotional Brand Attachment

5.4. Discussion of Study 3

6. Study 4a: Health Consciousness Effects—Scale Measurement Approach

6.1. Experimental Design and Procedure

6.2. Results of Study 4a

6.2.1. Main Effects Analysis in Study 4a

6.2.2. Test of the Moderating Effect of Health Consciousness

7. Study 4b: Reassessing Health Consciousness Through Priming Methodology

7.1. Research Objective of Study 4b

7.2. Experimental Design

- (1)

- For the low-health-consciousness condition, participants were presented with the following passage:

- (2)

- For the high-health-consciousness condition, participants were shown the following text:

7.3. Results of Study 4b

7.3.1. Manipulation Checks of Study 4b

- (1)

- Information Disclosure Manipulation

- (2)

- Health Consciousness Manipulation

7.3.2. Main Effects Analysis in Study 4b

7.3.3. Testing the Moderation of Health Consciousness

7.4. Discussion of Study 4b

- (1)

- Self-Licensing Account

- (2)

- Hedonic–Dominance Account

8. Conclusions and Discussion

8.1. General Conclusions

8.2. Theoretical Contribution

- (1)

- Redefining Transparency for “Negative Categories”

- (2)

- Attribution-Based Mechanism Insights

- (3)

- Boundary Conditions of Trust Building

8.3. Practical and Regulatory Implications

8.3.1. Implications for Regulators

8.3.2. Real-World Validation 1: Domino’s Cal-O-Meter

8.3.3. Real-World Validation 2: Heytea’s Caffeine Transparency Initiative

8.4. Limitations and Future Research Prospects

- (1)

- Sample Composition and Cultural Generalizability

- (2)

- Product Category Limitations

- (3)

- Absence of Behavioral Data

- Platform A/B tests, which collaborate with delivery apps (e.g., Meituan, Uber Eats) to vary disclosure formats while monitoring click-through and conversion rates;

- Eye-tracking studies, which capture whether transparency cues secure visual attention amid competing on-screen elements;

- Spillover analyses, which xamine whether upfront honesty about a focal item increases basket size or add-on purchases in digital carts.

- (4)

- Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Dai, X.; Wu, L.; Hu, W. Nutritional Quality and Consumer Health Perception of Online Delivery Food in the Context of China. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, U.; Ansari, A.R.; Fu, G.; Junaid, M. Feeling Hungry? Let’s Order through Mobile! Examining the Fast Food Mobile Commerce in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, A.; Ashour, A.; Tawfik Mohamed, D. Public Awareness, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Food Labeling, Alexandria, Egypt. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, M.; Annunziata, E.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M. Exploring the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Domains on Consumers’ Loyalty: An Experiment in BRICS Countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukabri, M.; Chaouachi, M. Exploring the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility, Blockchain Transparency, and Cultural Alignment on Consumer Trust and Premium Pricing Willingness for Local Food in Saudi Arabia. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2025, 13, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystallis, A.; Maglaras, G.; Mamalis, S. Motivations and Cognitive Structures of Consumers in Their Purchasing of Functional Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C.; Burton, S.; Howlett, E. It’s Only Natural: The Mediating Impact of Consumers’ Attribute Inferences on the Relationships between Product Claims, Perceived Product Healthfulness, and Purchase Intentions. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 698–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Fan, Z.-P.; Chen, Z. Implications of On-Time Delivery Service with Compensation for an Online Food Delivery Platform and a Restaurant. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 262, 108896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, W. The Effect of Information Overload on Consumer Choice Quality in an On-line Environment. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-H.; Lee, J. eWOM Overload and Its Effect on Consumer Behavioral Intention Depending on Consumer Involvement. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakály, Z.; Szente, V.; Kövér, G.; Polereczki, Z.; Szigeti, O. The Influence of Lifestyle on Health Behavior and Preference for Functional Foods. Appetite 2012, 58, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaylock, J.; Smallwood, D.; Kassel, K.; Variyam, J.; Aldrich, L. Economics, Food Choices, and Nutrition. Food Policy 1999, 24, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Araújo, R.; Lopes, F.; Ray, S. Nutrition and Food Literacy: Framing the Challenges to Health Communication. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. The Role of Health-Related, Motivational and Sociodemographic Aspects in Predicting Food Label Use: A Comprehensive Study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B.; Levy, A.S.; Derby, B.M. The Impact of Health Claims on Consumer Search and Product Evaluation Outcomes: Results from FDA Experimental Data. J. Public Policy Mark. 1999, 18, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Chandon, P. Can “Low-Fat” Nutrition Labels Lead to Obesity? J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozup, J.C.; Creyer, E.H.; Burton, S. Making Healthful Food Choices: The Influence of Health Claims and Nutrition Information on Consumers’ Evaluations of Packaged Food Products and Restaurant Menu Items. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Norman, P.; Webb, T.L. Using Temporal Self-Regulation Theory to Understand Healthy and Unhealthy Eating Intentions and Behaviour. Appetite 2017, 116, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Fu, Y.-K.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Information Asymmetry Evaluation in Hotel E-Commerce Market: Dynamics and Pricing Strategy under Pandemic. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanova, T.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Koufaris, M. Signaling Theory and Information Asymmetry in Online Commerce. Inf. Manag. 2012, 49, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Löbell-Behrends, S.; Böse, W.; Marx, G. Does European Union Food Policy Privilege the Internet Market? Suggestions for a Specialized Regulatory Framework. Food Control 2013, 30, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, Z. Public Health Risks Related to Food Safety Issues in the Food Market: A Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, D.L.; Dapko, J.L.; Arnold, R.W.; Arnold, D. Exploring Transparency: A New Framework for Responsible Business Management. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ferguson, M.A.T. Dimensions of Effective CSR Communication Based on Public Expectations. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 24, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, T.H. Strategic CSR Communication: A Moderating Role of Transparency in Trust Building. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Chau, P.Y.K. Does Altruism Matter on Online Group Buying? Perspectives from Egotistic and Altruistic Motivation. Inf. Technol. People 2015, 28, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D. Social Reporting and New Governance Regulation. Bus. Ethics Q. 2007, 17, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Swenson, R.; Anderson, B. What Happens When Brands Tell the Truth? Exploring the Effects of Transparency Signaling on Corporate Reputation for Agribusiness. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2019, 47, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, B.M.; Stroebe, W. Softening the Blow: Company Self-Disclosure of Negative Information Lessens Damaging Effects on Consumer Judgment and Decision Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A.P.; Miller, G.S.; Skinner, D.J. The Role of Supplementary Statements with Management Earnings Forecasts. J. Account. Res. 2003, 41, 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D.; Bourgeois, M.J.; Croyle, R.T. The Effects of Stealing Thunder in Criminal and Civil Trials. Law Hum. Behav. 1993, 17, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.S. Up Close and Personal on Social Media: When Do Politicians’ Personal Disclosures Enhance Vote Intention? Journal. Mass Commun. 2018, 95, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, L.; Espinosa, J.A.; Langenderfer, J.; Ortinau, D.J. Did You Hear Our Brand Is Hated? The Unexpected Upside of Hate-Acknowledging Advertising for Polarizing Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.H.; Hwang, C.Y. Nondisclosure and Adverse Disclosure as Signals of Firm Value. Rev. Financ. Stud. 1991, 4, 283–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, J.; Brühl, R. Can Bad News Be Good? On the Positive and Negative Effects of Including Moderately Negative Information in CSR Disclosures. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, I. Disclosure Strategies Regarding Ethically Questionable Business Practices. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. In The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, H.H. The Processes of Causal Attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. The Impact of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Commitment and the Moderating Role of Collectivism and Masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Khan, W.; Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, M.A.S. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Attributions on Employee’s Extra-Role Behaviors: Moderating Role of Ethical Corporate Identity and Interpersonal Trust. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Verma, S. The Intellectual Contours of Corporate Social Responsibility Literature: Co-Citation Analysis Study. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 1551–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginder, W.; Kwon, W.-S.; Byun, S.-E. Effects of Internal–External Congruence-Based CSR Positioning: An Attribution Theory Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.R.; Cheng, Y.; Hung-Baesecke, C.-J.F.; Jin, Y. Engaging International Publics via Mobile-Enhanced CSR (mCSR): A Cross-National Study on Stakeholder Reactions to Corporate Disaster Relief Efforts. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 1603–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Guo, Y. Perceived CSR Impact on Purchase Intention: The Roles of Perceived Effectiveness, Altruistic Attribution, and CSR-CA Belief. Acta Psychol. 2024, 248, 104414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidler, S.; Edinger-Schons, L.M. Partners in Crime? The Impact of Consumers’ Culpability for Corporate Social Irresponsibility on Their Boycott Attitude. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansome, K.; Wilkie, D.; Conduit, J. Beyond Information Availability: Specifying the Dimensions of Consumer Perceived Brand Transparency. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, N.; Dietz, G. Trust Repair After An Organization-Level Failure. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.; Gillespie, N.; Priem, R. Repairing Trust in Organizations and Institutions: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Organ. Stud. 2015, 36, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.-M.; Yeo, J. Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.; Vohs, K.D.; Mogilner, C. Nonprofits Are Seen as Warm and For-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Garbinsky, E.N.; Vohs, K.D. Cultivating Admiration in Brands: Warmth, Competence, and Landing in the “Golden Quadrant”. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Ahuvia, A.C. Some Antecedents and Outcomes of Brand Love. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K.; Chan, K.W. Strengthening Customer Loyalty through Intimacy and Passion: Roles of Customer–Firm Affection and Customer–Staff Relationships in Services. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrington, P.; Shim, S. An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship between Product Involvement and Brand Commitment. Psychol. Mark. 2000, 17, 761–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wei, X.; Lee, H. Revisiting the Elaboration Likelihood Model in the Context of a Virtual Influencer: A Comparison between High- and Low-Involvement Products. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 1638–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The Role of Health Consciousness, Food Safety Concern and Ethical Identity on Attitudes and Intentions towards Organic Food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Flores, B.; Chang, J.; Hwang, J. Communication through Restaurant Menus: Labeling and Psychology. Bus. Commun. Res. Pract. 2020, 3, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, C.; Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Yin, J.; Feng, H.; Dou, Z. COVID-19 Affected the Food Behavior of Different Age Groups in Chinese Households. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xue, L.; Jiang, Y.; Song, M.; Wei, D.; Liu, G. Food Delivery Waste in Wuhan, China: Patterns, Drivers, and Implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Luis Munuera-Alemán, J. Brand Trust in the Context of Consumer Loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Morwitz, V.G.; Kumar, V. Sales Forecasts for Existing Consumer Products and Services: Do Purchase Intentions Contribute to Accuracy? Int. J. Forecast. 2000, 16, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Sheeran, P. Does Changing Behavioral Intentions Engender Behavior Change? A Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-analytic Review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, J.; Nevin, J.R. Communication Strategies in Marketing Channels: A Theoretical Perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnackenberg, A.K.; Tomlinson, E.C. Organizational Transparency: A New Perspective on Managing Trust in Organization-Stakeholder Relationships. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1784–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T. An Empirical Analysis of Umbrella Branding. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Scharkow, M. The Relative Trustworthiness of Inferential Tests of the Indirect Effect in Statistical Mediation Analysis: Does Method Really Matter? Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, Z.; Phillipson, L. Are Big Food’s Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies Valuable to Communities? A Qualitative Study with Parents and Children. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 3372–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Kim, G.; Miao, L.; Behnke, C.; Almanza, B. Consumer Inferences of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Claims on Packaged Foods. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the Involvement Construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malär, L.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Nyffenegger, B. Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Personality: The Relative Importance of the Actual and the Ideal Self. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Consumer Attitudes Toward Health and Health Care: A Differential Perspective. J. Consum. Aff. 1988, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papies, E.K.; Potjes, I.; Keesman, M.; Schwinghammer, S.; Van Koningsbruggen, G.M. Using Health Primes to Reduce Unhealthy Snack Purchases among Overweight Consumers in a Grocery Store. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, B.; Lusk, J.L.; Davis, D. Looking at the Label and beyond: The Effects of Calorie Labels, Health Consciousness, and Demographics on Caloric Intake in Restaurants. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phy. 2013, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.; Dhar, R. Licensing Effect in Consumer Choice. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, S.; Evers, C.; De Ridder, D.T.D. Justified Indulgence: Self-Licensing Effects on Caloric Consumption. Psychol. Health 2019, 34, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebnitz, N.; Grunert, K.G. Impact of Self-Health Awareness and Perceived Product Benefits on Purchase Intentions for Hedonic and Utilitarian Foods with Nutrition Claims. Food Qual. Preference 2018, 64, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhart, F.; Malär, L.; Guèvremont, A.; Girardin, F.; Grohmann, B. Brand Authenticity: An Integrative Framework and Measurement Scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.S. Recent Attribution Research in Consumer Behavior: A Review and New Directions. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 14, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R.; Burnkrant, R.E.; Unnava, H.R. Consumer Response to Negative Publicity: The Moderating Role of Commitment. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 28050-2025; Food Safety National Standard for Nutrition Labelling of Prepackaged Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Mytton, O.T.; Boyland, E.; Adams, J.; Collins, B.; O’Connell, M.; Russell, S.J.; Smith, K.; Stroud, R.; Viner, R.M.; Cobiac, L.J. The Potential Health Impact of Restricting Less-Healthy Food and Beverage Advertising on UK Television between 05.30 and 21.00 Hours: A Modelling Study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Heytea: Revolutionizing the Beverage Industry With Innovation and Customer Engagement. In Cases on Chinese Unicorns and the Development of Startups; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 19–42. ISBN 9798369329214. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, C.; Ji, J.; Meng, X. Transparency as a Trust Catalyst: How Self-Disclosure Strategies Reshape Consumer Perceptions of Unhealthy Food Brands on Digital Platforms. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020133

Sun C, Ji J, Meng X. Transparency as a Trust Catalyst: How Self-Disclosure Strategies Reshape Consumer Perceptions of Unhealthy Food Brands on Digital Platforms. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(2):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020133

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Cong, Jinxi Ji, and Xing Meng. 2025. "Transparency as a Trust Catalyst: How Self-Disclosure Strategies Reshape Consumer Perceptions of Unhealthy Food Brands on Digital Platforms" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 2: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020133

APA StyleSun, C., Ji, J., & Meng, X. (2025). Transparency as a Trust Catalyst: How Self-Disclosure Strategies Reshape Consumer Perceptions of Unhealthy Food Brands on Digital Platforms. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(2), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020133