Abstract

In recent years, virtual anchors have become vital in live marketing due to their anthropomorphic features and interactive advantages. However, are anthropomorphic virtual anchors the best option? This study employs neuromarketing tools to examine the impact of virtual anchor appearance on consumer purchase intention, investigating the mediating role of emotional response and the moderating role of product type. The findings reveal the following: (1) the anthropomorphism level of virtual anchors is significantly positively correlated with purchase intention; (2) anthropomorphism exhibits a positive U-shaped relationship with emotional response, while inhuman images rapidly trigger emotional arousal, but this does not directly translate into purchase behavior; (3) for hedonic products, high anthropomorphism significantly increases purchase intention, whereas utilitarian products are more likely to be purchased when anthropomorphism is low. These findings provide a theoretical foundation for virtual anchor design, address the empirical gap regarding the interaction between anthropomorphism and product type, and offer scientific guidance for digital marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

The rapid rise of TikTok has transformed live-stream shopping into a significant online retail channel. The expansion of live-streaming has fostered a thriving anchor economy, with an increasing number of anchors leveraging their popularity to drive merchandise sales through live-streaming [1]. The integration of virtual anchors into digital media has been accelerated by advancements in artificial intelligence, machine learning, speech synthesis, and computer graphics [2]. Initially, virtual anchors were characterized by simplistic, cartoon-like appearances and mechanical voices. However, technological advancements have enabled them to develop highly realistic visuals, natural language expression, and emotional interaction capabilities, allowing for a more lifelike simulation of human behavior and an immersive user experience [3]. Nowadays, the image of virtual influencers has also gradually changed from pursuing high anthropomorphism to taking diversified forms and displaying more prosperous and diversified charms.

Unlike traditional human anchors, virtual anchors overcome time and space constraints, enabling round-the-clock broadcasting [4]. They also offer a high degree of flexibility and customization, allowing brands to tailor their appearance and communication style to align with specific marketing strategies [5].

In virtual anchor marketing, some studies have pointed out that anthropomorphism is a key factor influencing effectiveness [6,7,8,9]. A higher degree of anthropomorphism reflected in appearance, language style, and emotional expression enhances consumer emotional engagement and trust [10]. Psychological research suggests that humans naturally gravitate toward anthropomorphic features and form emotional connections, strengthening consumer identification with virtual anchors and potentially impacting purchasing decisions [11]. However, when virtual anchors exhibit a very low degree of anthropomorphism or display overtly non-human characteristics, they can still elicit complex emotional responses that warrant in-depth exploration and analysis. Positive emotional reactions, for instance, may arise from the novelty of the anchor’s unusual, non-human appearance or humorous elements embedded in their distinctive behavioral logic and interaction styles. Although these virtual anchors deviate significantly from human likeness, they can uniquely stimulate amusement and trigger positive emotional responses. These responses can be measured through electroencephalography (EEG), which captures fluctuations in brain activity [12]. EEG analysis offers a promising methodology for elucidating relationships between virtual anchor characteristics and consumer behavior. It transforms brain activity into visualized data using specialized equipment that captures signal changes at the moment consumers interact with the virtual anchor, thereby revealing their genuine emotional responses. This method reduces the subjective bias often associated with questionnaire-based research and provides greater accuracy than traditional approaches. Current research exhibits two critical gaps: insufficient investigation of nuanced connections between virtual anchor appearance and positive emotional responses, and limited understanding of anthropomorphism gradations’ behavioral impacts. This study aims to address this gap by exploring these dynamics through EEG analysis.

Furthermore, the marketing effectiveness of virtual anchors varies depending on product type [13]. Cosmetics and fashion products, for instance, rely more on the anchor’s persona and emotional appeal. At the same time, electronics and household goods emphasize functionality and rational decision-making [14]. Product category may function as a moderating variable between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention. However, the tripartite interaction among anchor anthropomorphism, affective responses, and product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic) remains understudied. Examining these relationships could yield strategic insights for optimizing virtual anchor marketing implementations.

This study examines the relationship between the virtual anchor appearance and consumer purchase intention, utilizing neuromarketing tools to investigate the mediating role of emotional response and the moderating role of product type. An experimental approach was adopted to collect data. The main experiment consisted of three parts: Study 1 explored the relationship between virtual anchor appearance (non-anthropomorphic vs. low-anthropomorphic vs. high-anthropomorphic) and consumers’ positive emotional responses; Study 2 examined the direct effect of appearance on purchase intention and whether positive emotional responses mediate this effect; Study 3 investigated the moderating role of the product type. Participants watched videos of virtual anchors with varying types of appearances while wearing EEG headgear to measure their emotional responses. The results indicate a positive correlation between virtual anchor appearance and consumer purchase intention, indicating that high anthropomorphism increases the likelihood of purchase. The results showed a positive U-shaped relationship between virtual anchor appearance and positive emotional responses. However, this is not the sole influence on consumers’ purchasing decisions. The product type also serves as a moderator, with the effect being more pronounced for hedonic products than utilitarian products.

First, this study reveals the positive correlation between the appearance of virtual anchors and consumers’ purchase intentions. Confirming the direct influence of anthropomorphic features on consumption decision-making provides empirical evidence for virtual image designers to optimize user interaction experiences, and enriches the theoretical understanding of the anthropomorphic effect within the field of human–computer interaction. Second, the study innovatively defines the application boundaries of anthropomorphic virtual anchors, demonstrates that emotional arousal is not necessarily linked to consumption conversion, challenges the cognitive bias that “emotional stimulation leads to purchase,” optimizes the functional positioning of virtual anchors, and highlights the limitations of relying solely on emotional appeals in decision-making. Finally, the study identifies the moderating role of product type (hedonic vs. utilitarian) on the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention, offering refined strategic guidance for tailoring virtual anchors across different product categories. This provides significant practical value in enhancing user engagement and improving platform operational effectiveness.

The paper is structured as follows: Chapter 2 reviews the literature, Chapter 3 presents the hypothesis development, Chapter 4 details the experimental design, methodology, and results, Chapter 5 discusses the findings, and Chapter 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Overview

2.1. Appearance of Virtual Anchors in Live-Streaming

In e-commerce, the rise of live-streaming commerce has been particularly significant, with anchors enhancing consumer engagement and purchase intention through real-time interaction and contextualized product displays [15]. With advancements in AI technology, virtual anchors have become an integral part of the live-streaming ecosystem. These digital hosts utilize computer-generated imagery, speech synthesis, facial capture, and real-time rendering to create highly realistic visual effects and behavioral patterns [16].

Unlike human anchors, virtual anchors offer distinct advantages, including the absence of time constraints, reduced privacy risks, and greater flexibility in design and branding [17]. However, most virtual anchors use anthropomorphic appearances, and the degree of anthropomorphism in virtual avatars varies significantly. Appearance is assessed based on how closely facial features and body proportions resemble human standards [18]. Verbal anthropomorphism is measured by analyzing the virtual anchor’s use of sensory language [19], while behavioral mimicry is evaluated through the smoothness of body movements and the richness of facial expressions [20]. Some studies have pointed out that anthropomorphic images of virtual anchors will enhance visual appeal and strengthen consumers’ cognitive acceptance and emotional connection [21].

However, increasing anthropomorphism does not always yield positive effects. Mori et al. proposed the Uncanny Valley theory, suggesting that avatars become highly human-like but retain subtle imperfections [22]. They may evoke discomfort rather than trust. This effect has been observed in virtual anchors, where excessive anthropomorphism can reduce trust and goodwill [23]. Conversely, Seymour et al. argue that the Uncanny Valley effect can be overcome [24]. Once anthropomorphism surpasses a certain threshold, user affinity increases significantly. Thus, discussing the appearance of virtual anchors is crucial for consumer acceptance. Most previous studies have focused on the anthropomorphism of static virtual images, with limited research on other types of virtual streamer appearances, which have not been uncommon in some real-time streaming media in recent years. Existing studies primarily compare virtual and human anchors in terms of consumer purchasing behavior, leaving a gap in understanding how virtual anchors’ other appearances influence explicit purchase decisions in live-streaming environments.

2.2. Product Function Types Based on Consumer Needs

In consumer behavior research, products are broadly categorized as hedonic or utilitarian based on their primary needs [25]. Hedonic products cater to consumers’ emotional needs and subjective experiences, offering pleasure, entertainment, or sensory enjoyment [26]. In contrast, utilitarian products address practical needs and functional goals, emphasizing efficiency and problem-solving capabilities [27].

Hedonic products attract consumers by delivering pleasurable experiences, satisfaction, and sensory stimulation [28]. Elements such as design, color, and packaging evoke strong emotional responses, fostering brand loyalty and enhancing the consumer experience [29,30]. In contrast, utilitarian products prioritize functionality, with purchasing decisions driven by cost–benefit analysis and specific attributes such as utilitarian, quality, durability, and price [31,32]. As a result, emotional factors play a lesser role, as consumers are primarily motivated by problem-solving and practical utility. Advertising strategies for utilitarian products often highlight utilitarian data, use cases, or cost-effectiveness comparisons to aid in rational decision-making [33]. Due to the higher perceived risk associated with functional purchases, consumers tend to invest more time and effort in evaluating options before making a decision [34]. With technological advancements, virtual anchors can exhibit varying levels of anthropomorphism, potentially influencing consumer purchase intentions. While previous studies have explored the basic applications of virtual anchors, research on how appearance affects purchase intention across different product categories remains limited. Therefore, this study investigates the moderating role of product type in the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention.

2.3. Measuring Emotional Response Using Neuroscience Tools

Emotional response is one of the central topics in the psychology of emotion, encompassing two key dimensions: emotional arousal and emotional contagion [35]. Emotional arousal refers to the physiological and cognitive reactions triggered by the valence and intensity of an external emotional stimulus [36]. Research indicates that high-arousal emotional stimuli like fear or excitement are more likely to capture attention and dominate memory processing. This phenomenon is believed to be an evolutionary adaptation that enhances an individual’s ability to respond quickly to threats or opportunities [37]. From a neurological perspective, the amygdala plays a crucial role in rapidly detecting and processing emotional stimuli, significantly influencing both the intensity and duration of emotional responses [38].

Emotional contagion, in contrast, refers to the transmission of emotions between individuals through direct or indirect interactions. Hatfield et al. proposed that emotional contagion often occurs through automatic facial expression mimicry [39], tone modulation, and postural adjustments, an unconscious social coordination mechanism that enables individuals to experience and adopt the emotions of others [40]. Empirical studies further suggest that emotional contagion plays a significant role in group decision-making, social interactions, and organizational behavior [41].

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a crucial neuroscience research tool for examining the relationship between consumers’ emotional responses and purchasing behaviors [42]. By recording electrical activity in the cerebral cortex, EEG captures consumers’ neural responses to various stimuli with high temporal resolution [43]. Early EEG research primarily focused on essential emotion recognition (e.g., happiness, sadness, anger, and fear), demonstrating that emotions generate distinct neural activity patterns in specific brain regions [44]. For instance, happiness is typically associated with increased activation in the left frontal lobe. In contrast, sadness is linked to proper frontal lobe activation [45].

In consumer behavior research, EEG has been increasingly used to analyze emotional responses to marketing stimuli, such as advertisements and product packaging [46]. When exposed to appealing advertisements, EEG recordings reveal changes in specific frequency bands (e.g., alpha, beta, theta), corresponding to variations in attentional focus and emotional arousal [47]. For example, alpha-wave suppression indicates heightened concentration and cognitive engagement. At the same time, beta-wave, on the other hand, is used to detect attentional-focus-related content and is generally associated with emotional responses such as pleasure and excitement, which detects the attractiveness of the material to the subject [48]. Existing research in the field of marketing indicates that beta waves can effectively monitor consumers’ pleasurable emotional responses. Damião De et al. discovered in an advertising experiment targeting beer consumers’ β-wave activity significantly increases when viewing advertisements that elicit pleasure emotions, suggesting that β-waves serve as a reliable physiological indicator for detecting pleasure emotions and then increased the participants’ visual interest in the brand and product packaging [49]. Kislov et al. found similar results in the neuro prediction of Internet users’ overall spending behavior, using beta-wave intensity to quantify pleasure levels [50]. Therefore, in live-streaming contexts, β-waves have the same effect and can measure the depth of emotional immersion and the immediate emotional resonance evoked by virtual anchors, influencing consumers’ purchase intentions. Given the high sensitivity of β-waves to emotional arousal, their data can intuitively reflect consumers’ immediate psychological responses to virtual anchor interactions, providing a neuroscientific foundation for optimizing anchor performance and content design. Accordingly, this study investigates and analyzes beta-wave activity to assess emotional responses.

Despite the growing application of EEG technology in marketing, research on EEG-based analysis of consumer responses to virtual anchors remains limited. However, real-time monitoring and quantitative analysis of consumers’ emotional feedback during interactions with avatars are essential [51]. Thus, employing EEG technology to examine the relationship between different degrees of anthropomorphism and consumer emotional responses is necessary. EEG enables the collection of precise neurophysiological data, providing a robust foundation for future research [52].

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Virtual Anchor Appearance Affects Purchase Intentions

With the rapid advancement of digitalization, the live e-commerce industry is experiencing significant growth, and virtual anchors have emerged as key tools for businesses to attract consumers and drive product sales [53]. Among the various factors influencing virtual anchors’ effectiveness, the impact of virtual anchor appearance on consumer purchase intention has garnered increasing attention. This relationship is supported by a multidisciplinary foundation, drawing from psychology and sociology [54].

Most studies indicate the positive effects of anthropomorphism on consumer attitudes and behaviors. For example, research on brand anthropomorphism has shown that when brands use anthropomorphic advertising images or marketing campaigns, consumer recall and favorability toward the brand significantly increase [55]. Applying this principle to virtual anchors, those with a high degree of anthropomorphism can communicate product information more effectively, improving consumer knowledge and understanding [56]. Moreover, their ability to interact more naturally with consumers fosters emotional resonance, increasing the likelihood that consumers will trust and accept the recommended products [57].

However, a few studies have pointed out the effect that non-anthropomorphic appearance has on consumer purchase intentions; so, based on the above theoretical and research bases, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1.

The degree of anthropomorphism in virtual anchors positively correlates with consumer purchase intention.

3.2. Appearance Triggers an Emotional Response and Influences Purchase Intention

The advent of virtual anchors on social media and e-commerce platforms, coupled with technological advancements, has led to a surge in the pursuit of virtual anchors that exhibit pronounced anthropomorphic characteristics. This phenomenon can be attributed to the belief that such virtual entities, with their highly human-like appearance, are poised to yield more efficacious outcomes. The present study hypothesizes that the extent to which virtual anchors exhibit anthropomorphic characteristics may substantially impact the relationship between consumers’ positive emotional responses and their purchasing decisions.

Anthropomorphism in virtual anchors refers to the extent to which they exhibit human-like characteristics in appearance, behavior, voice, and emotional expression [58]. Highly anthropomorphized virtual anchors can establish a more human-like emotional connection with viewers through tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language [59]. This emotional resonance may trigger emotional contagion and arousal effects, ultimately influencing consumer purchase intentions.

According to emotional contagion theory, individuals are easily influenced by others’ emotions, particularly in interactive environments [60]. Research has shown that the more anthropomorphic a virtual anchor appears, the more effectively it conveys emotions to the audience through non-verbal cues such as facial expressions, tone of voice, and movements, facilitating emotional resonance via the emotional contagion effect [61]. However, most scholars have tended to ignore the results from non-anthropomorphic virtual anchor images; they argue that these avatars have a lower capacity for emotional expression and may struggle to elicit strong emotional responses from viewers, weakening the emotional connection [62]. Nonetheless, this phenomenon’s specific effects and extent remain unclear, highlighting existing research gaps. Building on this, we argue that the appearance of a virtual anchor powerfully evokes positive emotional responses in viewers, particularly stimulating emotional arousal.

Emotional arousal is the intense and enduring emotional response elicited when viewers observe an avatar’s behavior or speech [63]. For instance, if an avatar conveys humor, warmth, or sadness, it can rapidly activate the viewer’s emotions [64], often leading to behavioral changes such as increased attention to the anchor, more significant interaction, or heightened interest in a recommended product. Research suggests that emotional arousal effectively enhances consumer purchase motivation, as intense emotional experiences are closely linked to irrational factors in decision-making [65]. In conjunction with the above, we propose that virtual anchors with different appearances elicit varying degrees of positive emotional responses, influencing consumer behavior.

Emotional response is central to consumer purchasing behavior, particularly in decision-making [66]. It significantly influences psychological processes such as attention allocation, memory processing, and risk perception, ultimately shaping consumer decisions [67]. It has been observed that when viewers exhibit strong emotional responses to virtual anchors, particularly under emotional contagion and emotional arousal, their attitudes and behaviors will likely shift, impacting their purchase decisions. Compared to adverse emotional reactions, positive emotional contagion or arousal enhances consumers’ affinity toward the promoted products or services, strengthens their identification with and trust in the virtual anchors, and ultimately increases their purchase intentions. Given these insights, we propose that varying appearances in virtual anchors evoke distinct positive emotional responses, influencing purchase intention. Based on the above background, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

The appearance of the virtual anchor affects positive emotional responses, which in turn affect purchase intentions.

3.3. Matching Effects of Virtual Anchor Appearance and Type of Product Functionality

The interaction between virtual anchor appearance and product type (hedonic vs. utilitarian) serves as a key boundary condition in explaining variations in consumer purchase intention. The matching effect theory suggests that optimal alignment between elements enhances decision-making processes. For example, when an endorser’s characteristics align with product attributes, processing fluency improves, leading to greater trust and increased purchase motivation [68]. However, the matching mechanism between virtual anchor appearance and product type is asymmetrical. Utilitarian products, which emphasize functionality and efficacy, require virtual anchors to convey professional credibility through anthropomorphism. In contrast, hedonic products, which focus on emotional and sensory appeal, may weaken the link between anthropomorphism and purchase intention [69].

Hedonic products are closely associated with emotional experiences, sensory enjoyment, and self-expression, leading consumers to rely more on affective and sensory stimuli in purchasing decisions [70]. In this context, virtual anchors with varying appearances evoke different consumer responses, with human-like characteristics fostering stronger emotional connections and increasing purchase motivation for hedonic products.

In contrast, the motivation to purchase utilitarian products is driven by rational considerations and practical needs [71]. Consumers prioritize functionality, cost-effectiveness, and technical specifications [72]. Highly anthropomorphic virtual anchors can reduce perceived information asymmetry by simulating real-life interactions, enhancing consumer trust in product utilitarianism [73]. Research suggests that more significant anthropomorphism reinforces perceptions of professionalism and credibility [74], aligning with the pragmatic demands of utilitarian products. Highly anthropomorphic avatars can maintain technological affinity while reinforcing product reliability [75].

Despite growing interest in virtual anchors, limited research has examined how virtual anchor appearance and product type shape consumer purchase behavior. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3.

Product type moderates the relationship between anthropomorphism and purchase intention.

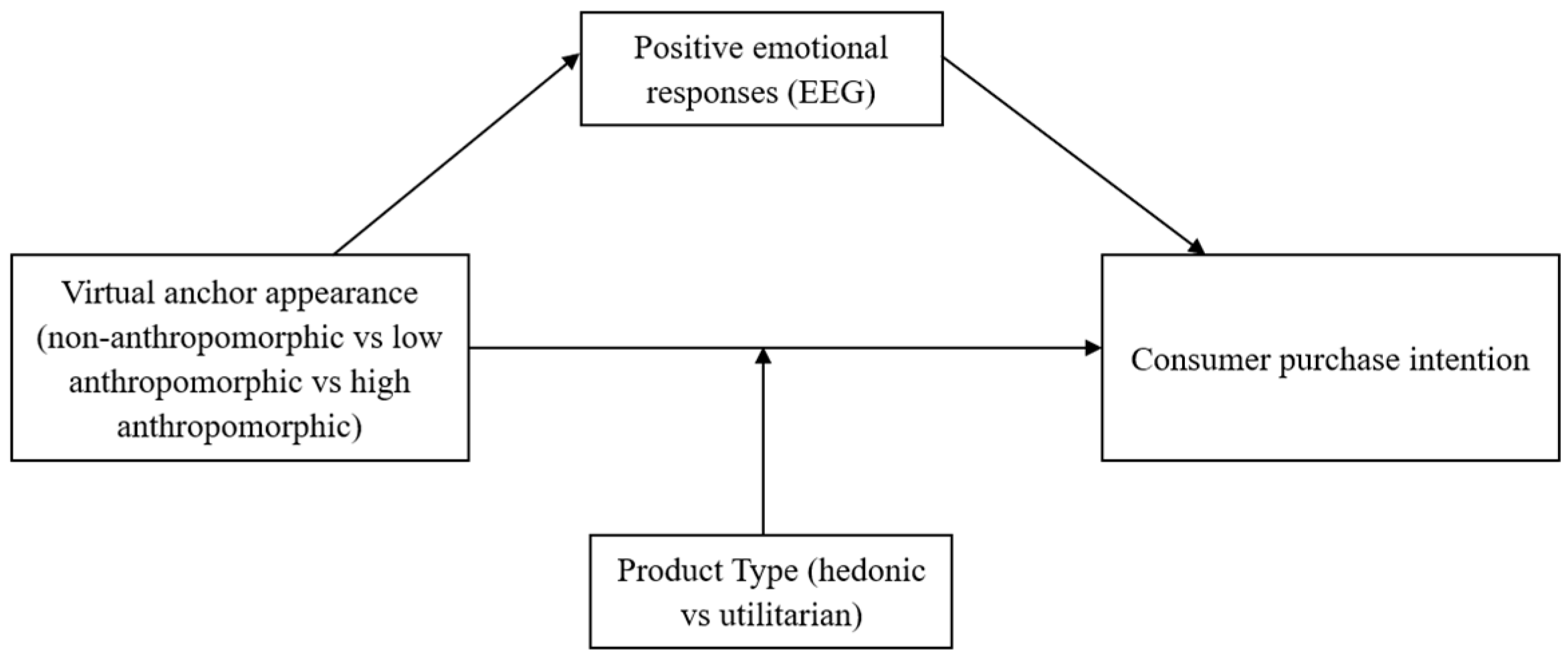

The conceptual framework of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the variable framework.

4. Research Design

4.1. Study 1

The aim of Study 1 was to investigate the correlation between virtual anchor appearance and positive consumer emotional responses. The study hypothesized that understanding which virtual anchors elicit stronger emotional reactions could help platforms design more appealing virtual anchors to attract consumers to engage with live-streaming content.

4.1.1. Design of Experiments in Study 1

In Study 1, a one-factor (non-anthropomorphic vs. low-anthropomorphic vs. high-anthropomorphic) between-subjects experimental design was employed to examine the relationship between appearance in virtual anchors and consumers’ positive emotional responses. Three virtual anchor images with varying appearances were created using a website. These images, accompanied by text and audio related to a Bluetooth headset, produced three video stimuli for a pretest (see Appendix A).

In the study, 187 participants were recruited, all with at least a bachelor’s degree, aged between 19 and 31 years. The study was conducted in a controlled laboratory setting to ensure a quiet environment and minimize external interference. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups and wore EEG devices to measure brain activity. They then watched videos of virtual anchors with varying levels of anthropomorphism presented on professional display equipment. The videos, each featuring the same live broadcast scene and product introduction, differed only in the appearance of the virtual anchor. In the first video, the virtual anchor was a non-anthropomorphic cartoon character. The second video featured a low-anthropomorphic anchor exhibiting smiling, blinking, and body movements. The third video presented a highly anthropomorphic virtual anchor with realistic facial expressions that naturally conveyed emotions such as happiness and sadness and smooth body movements aligned with verbal expressions. After watching the videos, participants completed an anthropomorphic scale and demographic information. Simultaneously, the EEG device recorded participants’ emotional responses throughout the study, capturing electrical potential changes in the brain in response to stimuli. This provided valuable data for further analysis of how virtual anchor appearance influences consumer emotions and behaviors.

The EEG device from the Credamo platform is a remote data acquisition tool that captures EEG activity in the prefrontal region through two electrode pads placed on the scalp. It samples approximately 250 data points per second, with a sampling interval of 4 ms. The raw EEG data undergoes preprocessing to remove low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise, minimizing the influence of non-brain signals, such as myoelectric activity and power interference. Following preprocessing, feature extraction is performed, where a window of 512 sampling points, including the current point and its preceding 511 points, is used. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is applied to analyze this window in the frequency domain, identifying typical EEG signals such as (4–7 Hz), (8–13 Hz), and (14–30 Hz), among other frequency bands. These bands represent the frequency-domain characteristics of the EEG at each moment. Since beta waves can detect the concentration of attention and are correlated with emotional responses such as pleasure and excitement, we focused on beta-wave data for the analysis in this paper. In addition to the authors, three experienced faculty members were invited to analyze the neuroimaging results independently, and the results of the data analysis were consistent with those of the authors of this study, which provided strong support for the reliability of the results.

4.1.2. Results Analysis of Study 1

To assess the effectiveness of virtual anchor appearance, we recruited 123 participants through the Credamo platform to pretest anthropomorphic images of virtual anchors. After excluding three participants who failed the attentional screening, the final valid sample consisted of 120 participants (67.5% women, Mage = 32 years, SDage = 8.77 years). These participants were randomly assigned to three groups and watched videos featuring virtual images with varying appearances. The Perceived Humanity scale, developed by Mike Seymour, measured their perceptions [24]. The scale demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient exceeding 0.8.

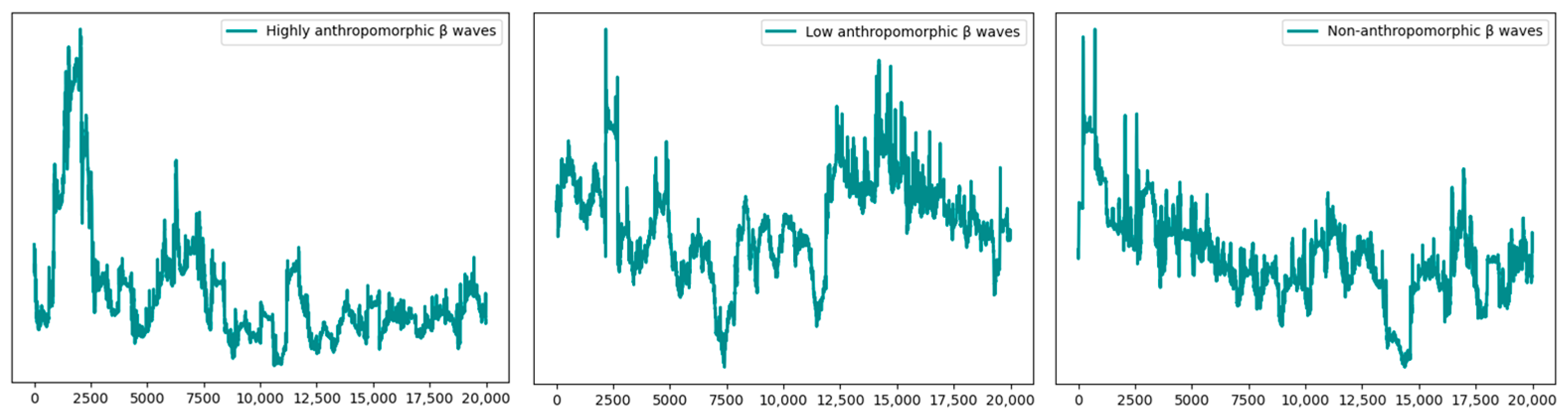

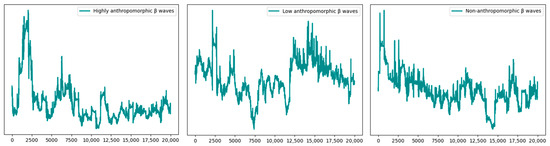

A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in consumers’ perceptions across the three virtual anchor appearances; consumers’ anthropomorphic perceptions of virtual anchors were significantly lower in the non-anthropomorphic condition than in the low- and high-anthropomorphic conditions (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 2.48, Mlow anthropomorphic = 2.81, Mhigh anthropomorphic = 3.60, F(2,117) = 18.81, p < 0.001). These findings confirm that manipulating the virtual anchor appearance in the experimental materials was successful. Following pretesting, EEG beta-wave results showed that highly anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic virtual anchors peaked quickly. In contrast, low-anthropomorphic images peak initially, but the beta wave rapidly diminishes over time.

Figure 2 shows the subjects’ beta-wave responses to virtual anchors with different degrees of anthropomorphism, and a comparative analysis of the EEG images of three different-looking virtual anchors revealed that, in the initial stage, the peak EEG activity of the non-anthropomorphism virtual image was significantly higher than that of the other two images. This finding suggests that avatars with non-anthropomorphism can trigger consumers’ emotional responses more rapidly. One possible explanation is that the non-anthropomorphism image differs more starkly from the human images consumers regularly encounter, making it more likely to attract attention and evoke positive emotional fluctuations in a short period. In contrast, virtual images with low to high anthropomorphism may be perceived in a more familiar and less stimulating manner, leading to a slower emotional response. Data processing was performed after the subjects filled out the collection of anthropomorphic scales after watching the video, and five participants who failed the attention test were excluded. The final valid sample consisted of 182 participants (71.99% women, Mage = 24 years, SDage = 2.06 years). This relationship was further examined through a one-way ANOVA on the beta-wave data of valid samples across different virtual anchor appearances. The analysis revealed significant differences in consumers’ emotional responses to the three types of virtual anchor appearances; consumers’ emotional responses were significantly lower in the low-anthropomorphic condition than in the non-anthropomorphic and high-anthropomorphic conditions (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 0.056, Mlow anthropomorphic = 0.008, and Mhigh anthropomorphic = 0.015, F(2,179) = 3.339, p < 0.05). The findings confirm a positive U-shaped relationship between virtual anchor appearance and positive emotional responses. Specifically, virtual anchors with either high-anthropomorphic or non-anthropomorphic appearances were more effective in eliciting positive emotional responses than those with low-anthropomorphic appearances.

Figure 2.

Different anthropomorphic beta-wave images.

4.2. Study 2

The objective of Study 2 was twofold: first, to examine the impact of virtual anchors’ appearance on purchase intention, and second, to ascertain the mediating role of positive emotional response in the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention. This investigation sought to elucidate the factors that influence consumers’ purchase intention.

4.2.1. Design of Experiments in Study 2

Study 2 employed a between-groups experimental design with a single independent variable: virtual anchor appearance (non-anthropomorphic vs. low-anthropomorphic vs. high-anthropomorphic). The objective was to examine the impact of virtual anchor images with varying virtual anchor appearances on consumers’ purchase intentions and to determine whether these differences elicited positive emotional responses that, in turn, influenced purchasing behavior.

This experiment built upon Study 1 by utilizing three virtual anchor videos with different virtual anchor appearances (Appendix A). One hundred and eighty-seven participants were recruited, all wearing EEG devices during the experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups, where they watched the assigned videos and subsequently completed a purchase intention scale and a demographic questionnaire [76].

4.2.2. Results Analysis of Study 2

The impact of virtual anchor appearance on consumers’ purchase intentions was first examined. A one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in purchase intentions across different levels of anthropomorphism (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 2.28, Mlow anthropomorphic = 3.10, Mhigh anthropomorphic = 3.14, F(2179) = 16.57, p < 0.001). Specifically, non-anthropomorphic product displays (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 2.28) scored the lowest on purchase intent, suggesting consumers are less interested in such products. In contrast, low-anthropomorphic product displays (Mlow anthropomorphic = 3.10) scored significantly higher on purchase intent, suggesting that moderate anthropomorphism effectively enhances consumers’ purchase intent. Notably, high-anthropomorphic (Mhigh anthropomorphic = 3.14) displays scored slightly higher than low-anthropomorphic ones, but the difference was insignificant. Overall, increased anthropomorphic levels significantly improve consumers’ purchase intention, especially during the transition from non-anthropomorphic to low-anthropomorphic conditions.

A pairwise comparison analysis showed that consumers exhibited significantly higher purchase intentions when exposed to a low anthropomorphized virtual anchor compared to a non-anthropomorphism virtual anchor (t(120) = 4.87, p < 0.001). Similarly, purchase intentions were significantly higher for the highly anthropomorphized virtual anchor compared to the non-anthropomorphism version (t(118) = 5.11, p < 0.001). These results suggest that virtual images resembling humans are more effective at stimulating consumer purchase intent than cartoon-like characters.

To examine whether positive emotional response mediates the relationship between anthropomorphism level and purchase intention, Study 2 employed Model 4 in PROCESS for a two-stage bootstrap mediation analysis, and the results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Brokered path results.

Moreover, the results showed that emotional responses decreased when transitioning from non-anthropomorphic to low-anthropomorphic anchors, but purchase intentions increased. Conversely, moving from low- to high-anthropomorphic anchors enhanced emotional responses and purchase intentions. These results suggest a significant relationship between virtual anchor appearance and positive emotional responses (β = −0.02, p < 0.05). However, the emotional response did not significantly mediate the effect of anthropomorphism on purchase intention, as the confidence interval included zero (LLCI = −1.23, ULCI = 1.25). Thus, the mediating effect was not statistically significant.

4.3. Study 3

The third experiment was conceived to investigate whether virtual anchor anthropomorphism’s effect on purchase intention is moderated by product type. Identifying this moderating mechanism would facilitate the development of distinct virtual anchors tailored to different product types to enhance purchase intentions.

4.3.1. Design of Experiments in Study 3

Study 3 employed a 2 × 3 between-subjects factorial design, with product type (hedonic vs. utilitarian) and anthropomorphism level (high, low, non) as independent variables. The objective was to examine whether product type moderates the effect of virtual anchor anthropomorphism on purchase intention (Appendix B).

The three anthropomorphism videos from Study 1 were reused, with their introductions modified to emphasize either hedonic or functional product attributes. The product featured in the videos was a pair of Bluetooth headphones. The hedonic condition emphasized the headphones’ aesthetic appeal and portability, while the functional condition highlighted their durability and versatility.

One hundred and eighty-seven participants, all with a bachelor’s degree, were recruited for the study. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups, watched a virtual anchor video corresponding to their assigned anthropomorphism level, and completed a purchase intention scale and a demographic questionnaire.

Based on pre-registered exclusion criteria, five subjects were excluded for failing the attention test before data analysis. This left 182 usable responses (71.99% women, Mage = 24 years, SDage = 2.06 years).

4.3.2. Results Analysis of Study 3

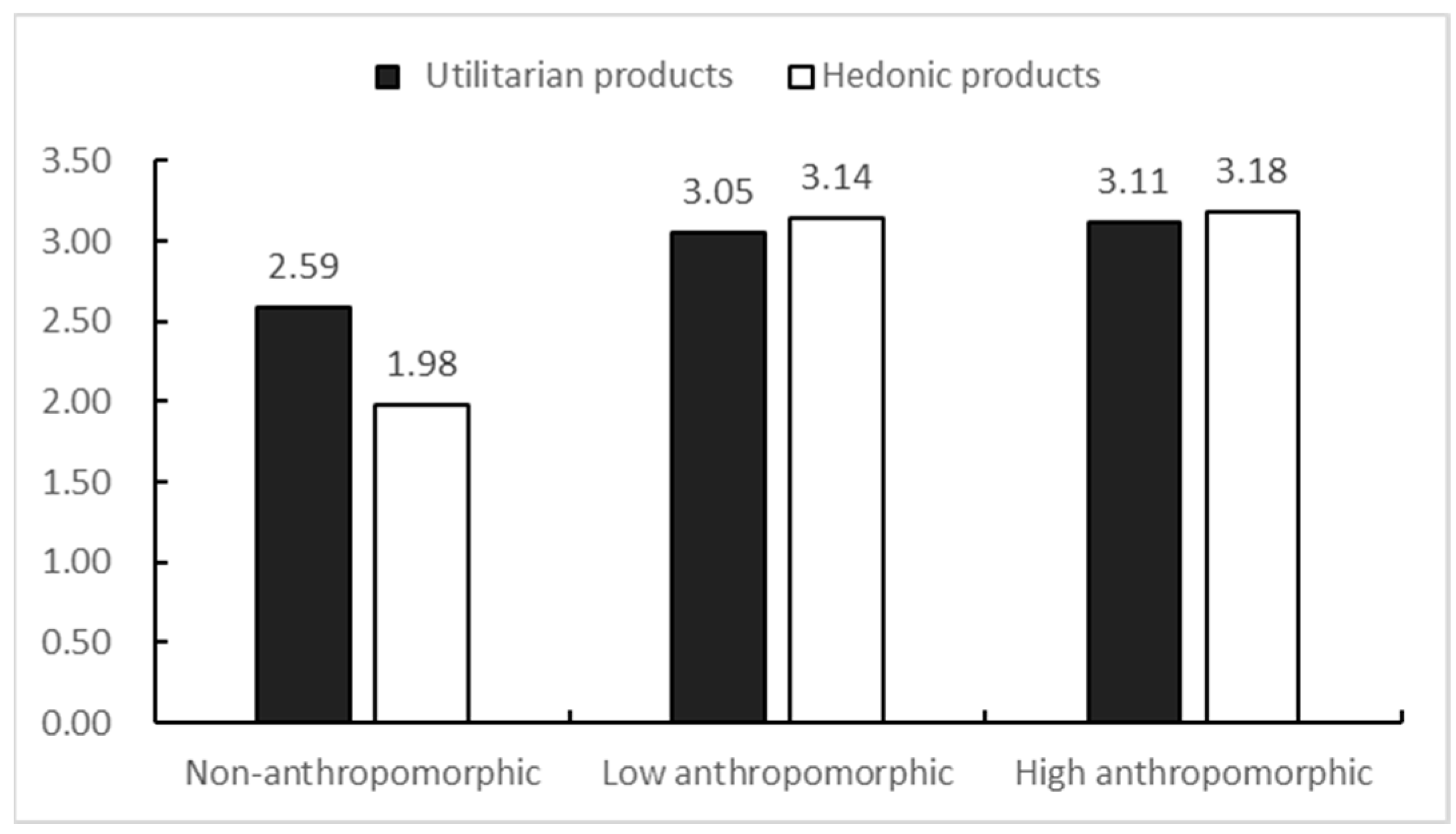

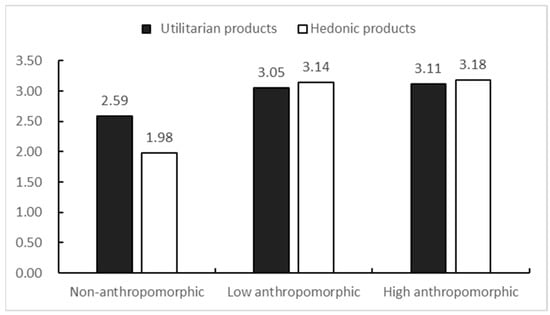

A two-way ANOVA was conducted with virtual anchor appearance (1 = non-anthropomorphic, 2 = low-anthropomorphic, 3 = high-anthropomorphic) and product type (0 = utilitarian, 1 = hedonic) as independent variables and purchase intention as the dependent variable. The results showed a significant main effect of virtual anchor appearance (F (2, 176) = 16.93, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.16), while the main effect of the product type was not significant. However, a significant interaction between virtual anchor appearance and product type was observed (F (2, 176) = 2.85, p < 0.1, η2 = 0.03).

Simple effects analyses revealed distinct patterns based on the appearance of virtual anchors. For non-anthropomorphic virtual anchors, purchase intentions for utilitarian products were significantly higher than for hedonic products (Mhedonic = 1.98, SDhedonic = 0.92 vs. Mutilitarian = 2.59, SDutilitarian = 1.13; F (1,176) = 6.72, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.37). In the low-anthropomorphic condition, although the moderating effect was not significant, participants still showed a slightly higher willingness to purchase hedonic products compared to utilitarian ones (Mhedonic = 3.14, SD hedonic = 0.77 vs. Mutilitarian = 3.05, SDutilitarian = 0.79; F(1,176) = 0.14, p = 0.71, η2 = 0.001). A similar pattern was observed in the high-anthropomorphic condition (Mhedonic = 3.18, SDhedonic = 0.87 vs. Mutilitarian = 3.11, SDutilitarian = 0.97; F(1,176) = 0.08, p = 0.78, η2 = 0.000).

Comparing the conditions, however, both the hedonic (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 1.98, SDnon-anthropomorphic = 0.92 vs. Mlow anthropomorphic = 3.14, SDlow anthropomorphic = 0.77 vs. Mhigh anthropomorphic = 3.18, SDhigh anthropomorphic = 0.87; F (2,176) = 16.82; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.16) and utilitarian product (Mnon-anthropomorphic = 2.59, SDnon-anthropomorphic = 1.13 vs. Mlow anthropomorphic = 3.05, SDlow anthropomorphic = 0.79 vs. Mhigh anthropomorphic = 3.11, SDhigh anthropomorphic = 0.97; F (2,176) = 2.96; p < 0.1; η2 = 0.03) purchase intentions were significantly higher in the anthropomorphic condition compared to the non-anthropomorphic condition (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Different anthropomorphic and purchase intentions for different products.

5. Discussion

In recent years, there has been an increase in research on virtual human beings, most of which either compares virtual human beings with real people or analyzes which factors of virtual human beings affect consumer purchasing behavior. In contrast, this study empirically examines the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention using an experimental approach. Additionally, it explores the mediating role of emotional response (measured via EEG) and the moderating role of product type. The findings indicate that anthropomorphism is positively associated with purchase intention. It was found that non-anthropomorphic levels of virtual anchors aroused positive emotional responses more quickly, but high anthropomorphic arousal of positive emotional responses lasted the longest, and positive emotional responses did not significantly affect purchase intentions. Furthermore, the moderating effect of the product type is more pronounced for hedonic products, suggesting that anthropomorphism substantially impacts purchase intention in this context. These insights contribute to the theoretical understanding of virtual anchor marketing and offer practical implications for businesses seeking to optimize virtual influencer strategies.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study offers three key contributions to academic research. First, this study integrates the literature on virtual anchors and live-streaming e-commerce to examine how different dimensions of virtual anchor design influence consumer behavior. The findings align with previous research suggesting that anthropomorphic virtual endorsers enhance brand attitudes and purchase intentions [77,78], but contrast with studies arguing that less- or non-anthropomorphic characters are more persuasive in specific contexts [79,80]. This study demonstrates that the appearance of virtual anchors significantly affects consumers’ immersive experiences, with higher levels of anthropomorphism associated with increased purchase intentions. This effect may be attributed to the ability of highly anthropomorphic virtual anchors to simulate realistic interactions through human-like appearances, voices, and behaviors, thereby fostering stronger consumer engagement. Notably, the influence of anthropomorphism on purchase intention is especially pronounced for hedonic products, likely because these products emphasize emotional experiences and sensory pleasures. By enhancing consumers’ immersion, highly anthropomorphic virtual anchors increase the likelihood of purchase behavior. These findings contribute new theoretical insights into the role of anthropomorphism in driving consumer engagement and purchase decisions within virtual marketing environments.

Second, this study investigates the mediating role of emotional responses in the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention, using beta-wave activity in EEG as a measure. The results indicate that while anthropomorphic virtual anchors quickly elicit positive emotional responses, these responses do not directly translate into purchase intentions. This finding aligns with affective cognition theory, which posits that emotional reactions alone are insufficient to trigger purchasing behavior; instead, the subsequent cognitive appraisal ultimately informs decision-making [81]. Thus, in live-streaming virtual environments, emotional responses reflected by EEG beta-wave activity should be viewed as precursors to cognitive processing rather than direct predictors of behavior, underscoring the primacy of cognitive factors in virtual purchase decisions.

Finally, this study examines the moderating role of product type in the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention. The results suggest that utilitarian and hedonic products activate distinct cognitive and affective responses in virtual marketing contexts. Specifically, for utilitarian products, non-anthropomorphic virtual anchors enhance cognitive processing by offering detailed explanations and interactive engagement, thereby increasing purchase intentions. In contrast, anthropomorphic virtual anchors amplify consumers’ immersive experiences through human-like interactions with hedonic products, strengthening user engagement and facilitating purchase behavior. These findings extend arousal theory by suggesting that in virtual marketing, purchase decisions are shaped by emotional arousal and cognitive appraisal, including factors such as brand trust and perceived product utility [82]. This insight advances our understanding of the emotional–cognitive mechanisms underlying consumer behavior in digital environments and offers practical guidance for selecting virtual anchors and designing product promotion strategies.

5.2. Practical Implications

The study of virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention has significant implications for marketing and promotion. This research highlights three key insights. First, the findings demonstrate that higher degrees of anthropomorphism in virtual anchors are associated with greater consumer purchase intention. This suggests that anthropomorphism enhances virtual anchors’ perceived warmth and approachability and strengthens emotional connections with audiences. To maximize the impact on purchase intention, businesses should design virtual anchors that align with product characteristics and target consumer demographics. For instance, incorporating expressive features such as eye movements, facial expressions, tone of voice, and emotive language can evoke emotional resonance, increasing consumer engagement and prompting purchasing behavior. This effect is particularly pronounced among younger consumers, for whom anthropomorphism captures attention and fosters brand identification through emotional interactions, ultimately increasing the likelihood of purchase.

Second, the study reveals that anthropomorphism more substantially affects purchase intention for hedonic products than utilitarian products. This insight provides strategic guidance for brands in selecting and designing virtual anchor representations. A highly anthropomorphized virtual anchor can enhance consumer immersive experiences and influence purchase decisions for hedonic products such as cosmetics and entertainment content. Conversely, while anthropomorphism positively impacts purchase intention for utilitarian products (e.g., electronic devices, household appliances), its effect is relatively weaker. Therefore, brands may benefit from using moderately anthropomorphic virtual anchors for marketing optimization when promoting utility products.

Finally, although non-anthropomorphic virtual anchors can elicit rapid positive emotional responses, these responses do not directly translate into purchase intention. This suggests that evoking pure emotional reactions may not be sufficient to drive purchasing behaviors. Consequently, businesses should prioritize the thoughtful design of virtual anchors’ anthropomorphic features rather than merely focusing on triggering immediate positive emotional responses. Fostering deeper emotional connections and reinforcing brand identity can significantly enhance purchase intention, particularly for virtual anchors with moderate to high anthropomorphism. Additionally, brands can cultivate long-term consumer trust and affinity toward virtual anchors through continuous interaction and emotional engagement. This sense of attachment can subtly reinforce purchasing decisions, making virtual anchors a robust digital marketing and brand-building tool.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

While this study employed experimental methods and EEG techniques to examine the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and purchase intention, along with the mediating role of affective response and the moderating role of product type, it has certain limitations.

First, the study relied solely on EEG to measure affective responses, which may not fully capture the complexity of consumers’ emotional states. Additionally, the accuracy of emotional response measurements may be influenced by equipment limitations and the experimental environment. Future research should adopt a multimodal approach by integrating various physiological measurement techniques (e.g., facial expression analysis, physiological sensors) alongside psychological scales to assess emotional responses across multiple dimensions, such as pleasantness and arousal. This would improve both the reliability and comprehensiveness of the findings.

Second, the study did not account for external environmental factors, such as social and cultural trends or competitive market activities, which may influence consumer purchase intentions. To improve generalizability and applicability, future research should expand the sample to include consumers from diverse demographic backgrounds varying in age, gender, geographic location, cultural context, and purchasing power. Additionally, incorporating external environmental variables would provide a more holistic understanding of the factors shaping consumer decision-making in virtual marketing contexts.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the impact of virtual anchor appearance on consumer purchase intention. Through a series of experimental designs and data analyses, several key conclusions were reached.

The study confirms the significant correlation between virtual anchor appearance and consumer purchase intention. Highly anthropomorphic virtual anchors lead to higher consumer purchase intentions. On the other hand, non-anthropomorphic appearance did not have a significant positive effect on consumers’ purchase intention, although the results of the EEG measure suggested that it would lead to higher emotional responses. Furthermore, product type effectively moderated the relationship between virtual anchor appearance and consumers’ purchase intention, with hedonic products positively contributing to their relationship more effectively. By enriching theoretical research in virtual anchor marketing, this study also provides practical insights for businesses seeking to integrate virtual anchors into marketing strategies. The findings suggest that companies should carefully design virtual anchors to align with both product characteristics and consumer expectations, optimizing their anthropomorphic features to maximize marketing effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z. and S.B.; methodology, J.Z. and L.C.; software, L.C.; formal analysis, L.C. and J.Z.; data curation, J.Z. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, J.Z; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number 23BJY151]: Shizhen Bai.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, and there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Videos of different appearances of virtual anchors introducing the same Bluetooth headset.

Table A1.

Videos of different appearances of virtual anchors introducing the same Bluetooth headset.

| Non-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/G1MIDty0 accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| Low-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/i8XjrYuU accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| High-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/JBKZ9RmY accessed on 14 November 2024 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Different appearances of virtual anchors introduce different product types of Bluetooth headset videos.

Table A2.

Different appearances of virtual anchors introduce different product types of Bluetooth headset videos.

| Non-Anthropomorphism Virtual Host Introduces Performance Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/G1MIDty0 accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| Low-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor Introduces Performance-Based Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/i8XjrYuU accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| High-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor Introduces Performance Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/JBKZ9RmY accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| Non-Anthropomorphism Virtual Host Introduces Hedonic Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/uLGprcgW accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| Low-Anthropomorphism Anchor Introduces Hedonic Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/lnlDGQnZ accessed on 14 November 2024 |

| High-Anthropomorphism Virtual Anchor Introducing Hedonic Products |  | https://www.yitulu.com/t/portfolio/Q27Cokud accessed on 14 November 2024 |

References

- Ma, E.; Liu, J.; Li, K. Exploring the Mechanism of Live Streaming E-Commerce Anchors’ Language Appeals on Users’ Purchase Intention. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1109092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, J. Virtual Human on Social Media: Text Mining and Sentiment Analysis. Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Liu, J. Virtual Human: A Comprehensive Survey on Academic and Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 123830–123845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Cao, C.; Xu, Q.; Ni, L.; Shao, X.; Shi, Y. How Live Streaming Interactions and Their Visual Stimuli Affect Users’ Sustained Engagement Behaviour—A Comparative Experiment Using Live and Virtual Live Streaming. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koek, W.J.D.; Chen, V.H.H. My Avatar Makes Me Feel Good? The Effect of Avatar Personalisation and Virtual Agent Interactions on Self-Esteem. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 44, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Oh, H. Anthropomorphism and Its Implications for Advertising Hotel Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulan, M.; Feng, Y.; Mvondo, G.F.N.; Niu, B. How Do Virtual Influencers Affect Consumer Brand Evangelism in the Metaverse? The Effects of Virtual Influencers’ Marketing Efforts, Perceived Coolness, and Anthropomorphism. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y. More Realistic, More Better? How Anthropomorphic Images of Virtual Influencers Impact the Purchase Intentions of Consumers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 3229–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Kuai, L.; Jiang, L. Effects of the Anthropomorphic Image of Intelligent Customer Service Avatars on Consumers’ Willingness to Interact after Service Failures. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 734–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, F. The Impact of Virtual Streamer Anthropomorphism on Consumer Purchase Intention: Cognitive Trust as a Mediator. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Basso Ricci, E.; Colombo, E.S. The Complexity of the Human–Animal Bond: Empathy, Attachment and Anthropomorphism in Human–Animal Relationships and Animal Hoarding. Animals 2022, 12, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. An Empirical Analysis of Psychological Factors Based on EEG Characteristics of Online Shopping Addiction in E-Commerce. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, S. The Influence of the Language Style of the Anchor on Consumers’ Purchase Intention. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1370712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. The Influence of Anthropomorphic Appearance of Artificial Intelligence Products on Consumer Behavior and Brand Evaluation under Different Product Types. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Ye, H.J. Transparentizing the “Black Box” of Live Streaming: Impacts of Live Interactivity on Viewers’ Experience and Purchase. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 3820–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chai, J.; Cao, X. Live Speech Portraits: Real-Time Photorealistic Talking-Head Animation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Q. Impact of AI-Oriented Live-Streaming E-Commerce Service Failures on Consumer Disengagement—Empirical Evidence from China. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1580–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Meng, J.; Cheah, J. From Virtual Trainers to Companions? Examining How Digital Agency Types, Anthropomorphism, and Support Shape Para-Social Relationships in Online Fitness. Psychol. Mark. 2025, 42, 842–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, A. How to Leverage Anthropomorphism for Chatbot Service Interfaces: The Interplay of Communication Style and Personification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 149, 107954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, U.; Minutolo, A.; Storniolo, P.; Esposito, M. Towards a More Anthropomorphic Interaction with Robots in Museum Settings: An Experimental Study. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 171, 104561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Song, T.; Wang, H. Alone or Mixed? The Effect of Digital Human Narrative Scenarios on Chinese Consumer Eco-Product Purchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1734–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; MacDorman, K.; Kageki, N. The Uncanny Valley [From the Field]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, R.; Riedel, A.; Keating, B.; Beatson, A.; Letheren, K. Avoiding Excessive AI Service Agent Anthropomorphism: Examining Its Role in Delivering Bad News. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2023, 34, 98–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, M.; Yuan, L.I.; Dennis, A.R.; Riemer, K. Have We Crossed the Uncanny Valley? Understanding Affinity, Trustworthiness, and Preference for Realistic Digital Humans in Immersive Environments. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, T.; Guo, J. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Continuous Purchase Intention on Fresh Food e-Commerce Platforms: An Organic Foods-Centric Empirical Investigation. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 50, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. Revealing Consumers’ Hedonic Buying in Social Media: The Roles of Social Status Recognition, Perceived Value, Immersive Engagement and Gamified Incentives. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Filieri, R.; Acikgoz, F.; Zollo, L.; Rialti, R. The Effect of Utilitarian and Hedonic Motivations on Mobile Shopping Outcomes. A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Chung, H. Understanding Experiential Consumption: Theoretical Advancement and Practical Implication. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1173–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.; Gao, Y. Exploring the Hedonic Factors Affecting Customer Experiences in Phygital Retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, R.B.; Kasamani, T. Brand Experience and Brand Loyalty: Is It a Matter of Emotions? Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid Sameeni, M.; Ahmad, W.; Filieri, R. Brand Betrayal, Post-Purchase Regret, and Consumer Responses to Hedonic versus Utilitarian Products: The Moderating Role of Betrayal Discovery Mode. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Morgado, Á.; González-Benito, Ó.; Martos-Partal, M.; Campo, K. Which Products Are More Responsive to In-Store Displays: Utilitarian or Hedonic? J. Retail. 2021, 97, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Ibáñez-Zapata, J.-Á. It Is All about Our Impulsiveness—How Consumer Impulsiveness Modulates Neural Evaluation of Hedonic and Utilitarian Banners. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Abbasi, A.; Cheema, A.; Abraham, L.B. Path to Purpose? How Online Customer Journeys Differ for Hedonic Versus Utilitarian Purchases. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Gu, Q.; Han, W.; Zhu, Y. The AI Empathy Effect: A Mechanism of Emotional Contagion. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 703–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorette, P.; Dewaele, J.-M. Valence and Arousal Perception among First Language Users, Foreign Language Users, and Naïve Listeners of Mandarin across Various Communication Modalities. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 2024, 27, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, M. Emotional Arousal and Memory Binding: An Object-Based Framework. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretié, L.; Yadav, R.K.; Méndez-Bértolo, C. The Missing Link in Early Emotional Processing. Emot. Rev. 2021, 13, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional Contagion. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1993, 2, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Q.; Li, M. Meaningful Body Talk: Emotional Experiences with Music-Based Group Interactions. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. What Is the Role of Emotions in Educational Leaders’ Decision Making? Proposing an Organizing Framework. Educ. Adm. Q. 2021, 57, 372–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, A.N.; Sung, B.; Hooshmand, R. A Practical Review of Electroencephalography’s Value to Consumer Research. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2023, 65, 52–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.; Barma, S. Review on Stimuli Presentation for Affect Analysis Based on EEG. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 51991–52009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Sarkar, A.K.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Islam, M.R.; Hossain, M.B.; Quinn, J.M.W.; Moni, M.A. Recognition of Human Emotions Using EEG Signals: A Review. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiblanco Jimenez, I.A.; Olivetti, E.C.; Vezzetti, E.; Moos, S.; Celeghin, A.; Marcolin, F. Effective Affective EEG-Based Indicators in Emotion-Evoking VR Environments: An Evidence from Machine Learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 22245–22263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.J.C.; Antonovica, A.; Martín, D.L.S. Consumer Neuroscience on Branding and Packaging: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2790–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Khraiwish, A. Consumer Behaviour to Be Considered in Advertising: A Systematic Analysis and Future Agenda. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C. Emotional Contagion Triggered by Online Consumer Reviews: Evidence from a Neuroscience Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damião De Paula, A.L.; Lourenção, M.; De Moura Engracia Giraldi, J.; Caldeira De Oliveira, J.H. Effect of Emotion Induction on Potential Consumers’ Visual Attention in Beer Advertisements: A Neuroscience Study. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 202–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kislov, A.; Gorin, A.; Konstantinovsky, N.; Klyuchnikov, V.; Bazanov, B.; Klucharev, V. Central EEG Beta/Alpha Ratio Predicts the Population-Wide Efficiency of Advertisements. Brain Sci. 2022, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Zhang, Y.; Gunasekaran, T.S.; Krishna, N.; Pai, Y.S.; Billinghurst, M. CAEVR: Biosignals-Driven Context-Aware Empathy in Virtual Reality. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2024, 30, 2671–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau-González, P.; Katsigiannis, S.; Arevalillo-Herráez, M.; Ramzan, N. BED: A New Data Set for EEG-Based Biometrics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12219–12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Chu, C.; Ding, X.; Shi, Y. Leave or Stay? Factors Influencing Consumers’ Purchase Intention during the Transformation of a Content Anchor to a Live Stream Anchor. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 1871–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jiang, N.; Guo, Q. How Do Virtual Streamers Affect Purchase Intention in the Live Streaming Context? A Presence Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.-E.; Cui, G.-Q.; Jin, C.-H. The Role of Human Brands in Consumer Attitude Formation: Anthropomorphized Messages and Brand Authenticity. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1923355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-P.; Xin, L.; Wang, H.; Park, H.-W. Effects of AI Virtual Anchors on Brand Image and Loyalty: Insights from Perceived Value Theory and SEM-ANN Analysis. Systems 2025, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Xie, Q.; Hong, J.-W.; Kim, H.M. Prosocial Campaigns with Virtual Influencers: Stories, Messages, and Beyond. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On Seeing Human: A Three-Factor Theory of Anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Li, Y.; Jin, H. What Do You Think of AI? Research on the Influence of AI News Anchor Image on Watching Intention. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, H.A. The Many Faces of Emotional Contagion: An Affective Process Theory of Affective Linkage. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 4, 326–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Zhang, F.; Fan, X.; Liu, F. Artificial Intelligence Psychological Anthropomorphism: Scale Development and Validation. Serv. Ind. J. 2024, 44, 1061–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Min, Q.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Q. The Effect of the Anthropomorphic Design of Chatbots on Customer Switching Intention When the Chatbot Service Fails: An Expectation Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda-Ángeles, M.; Aleix-Guillaume, S.; Pereda-Baños, A. Users’ Psychophysiological, Vocal, and Self-Reported Responses to the Apparent Attitude of a Virtual Audience in Stereoscopic 360°-Video. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, T.; Guan, Y.; Cui, X. How Do Virtual AI Streamers Influence Viewers’ Livestream Shopping Behavior? The Effects of Persuasive Factors and the Mediating Role of Arousal. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 1803–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Gu, M.; Yang, J. Research on the Influence Mechanism of Anchors’ Professionalism on Consumers’ Impulse Buying Intention in the Livestream Shopping Scenario. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 2065457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y. Positive Emotion Bias: Role of Emotional Content from Online Customer Reviews in Purchase Decisions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Xu, Z.; Huang, H. How Does Information Overload Affect Consumers’ Online Decision Process? An Event-Related Potentials Study. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 695852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It Is a Match: The Impact of Congruence between Celebrity Image and Consumer Ideal Self on Endorsement Effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shao, B.; Yang, X.; Kang, W.; Fan, W. Avatars in Live Streaming Commerce: The Influence of Anthropomorphism on Consumers’ Willingness to Accept Virtual Live Streamers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 156, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Chen, L. Do Consumers Prefer Sad Faces On Eco-Friendly Products?: How Facial Expressions on Green Products In Advertisements Influence Purchase Intentions. J. Advert. Res. 2023, 63, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.M. Justification Effects on Consumer Choice of Hedonic and Utilitarian Goods. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, F.; Gigliotti, M.; Runfola, A.; Ferrucci, L. Don’t Miss the Boat When Consumers Are in-Store! Exploring the Use of Point-of-Purchase Displays to Promote Green and Non-Green Products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Pu, Y.; Qi, Y. Trust in Human and Virtual Live Streamers: The Role of Integrity and Social Presence. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 8274–8294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Supervising or Assisting? The Influence of Virtual Anchor Driven by AI–Human Collaboration on Customer Engagement in Live Streaming e-Commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, B.; Shelat, M.-P.; Bansal, A. Virtual Influencers: A Design Study Using Anthropomorphism and Self-Congruence Perspectives. J. Strateg. Mark. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yang, Y. The Impact of Customer Experience on Consumer Purchase Intention in Cross-Border E-Commerce—Taking Network Structural Embeddedness as Mediator Variable. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. How Technical Features of Virtual Live Shopping Platforms Affect Purchase Intention: Based on the Theory of Interactive Media Effects. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 180, 114189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually Human: Anthropomorphism in Virtual Influencer Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Tang, Y. Avatar Effect of AI-Enabled Virtual Streamers on Consumer Purchase Intention in e-Commerce Livestreaming. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2999–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hikkerova, L. AI or Human: How Endorser Shapes Online Purchase Intention? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsou, R.H.; Hatzithomas, L.; Wetzels, M. Display Advertising: The Role of Context and Advertising Appeals from a Resistance Perspective. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheka, T.; Quaye, E.S.; Ligaraba, N. The Effect of Online Customer Reviews and Celebrity Endorsement on Young Female Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).