Effect of E-Servicescape on Emotional Response and Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. E-Servicescape

2.2. Emotional Response

2.3. Revisit Intention

2.4. Internet Shopping Mall

2.5. Effect of the E-Servicescape on Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall

3. Research Methodology

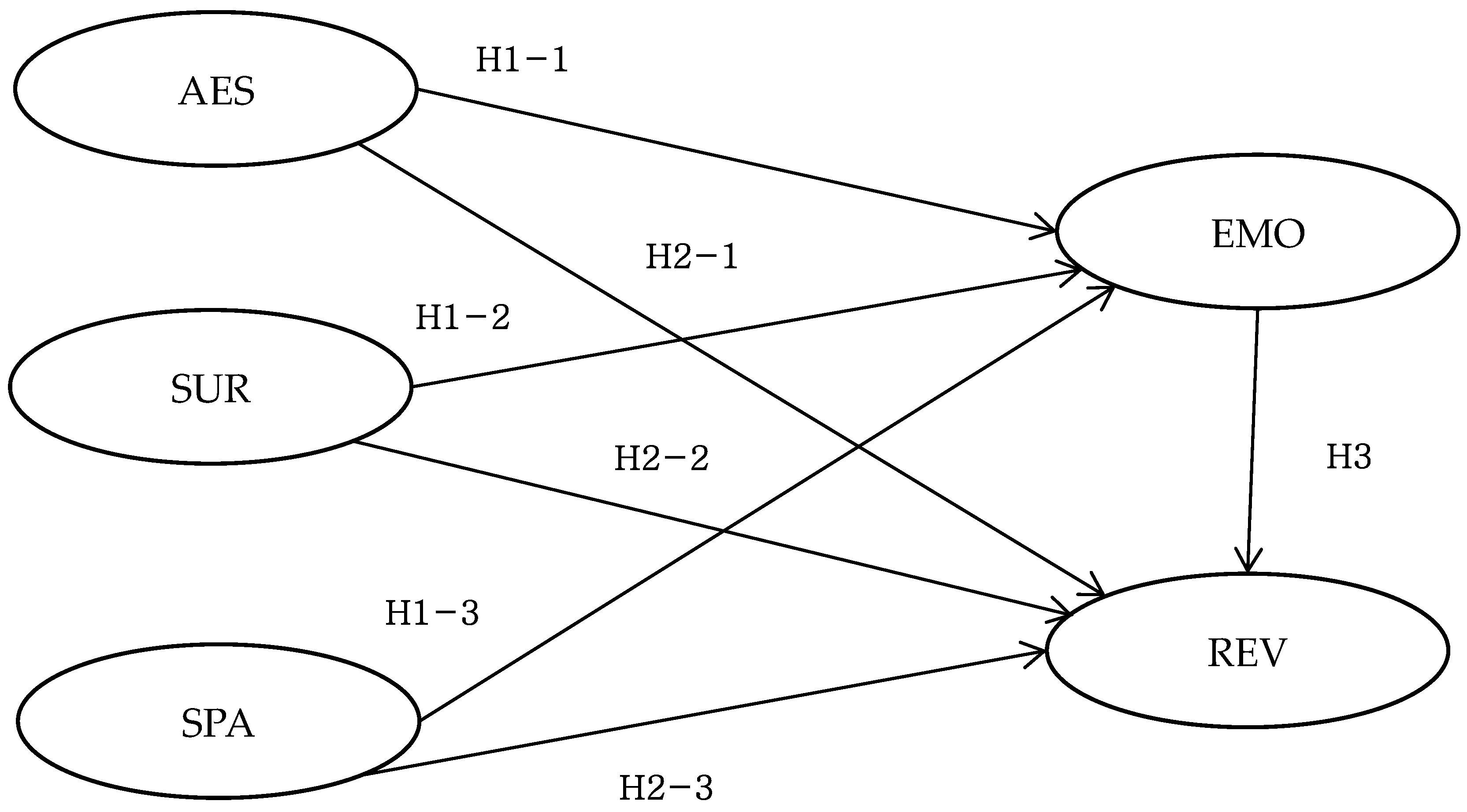

3.1. Hypotheses Development and Research Model

3.1.1. Relationship between Components of the E-Servicescape and Emotional Responses

3.1.2. Relationship between the Components of the E-Servicescape and Revisit Intention

3.1.3. Relationship between Emotional Responses and Revisit Intention

3.2. Operational Definitions of Measurements

3.2.1. Aesthetics

3.2.2. Surrounding Elements

3.2.3. Spatial Functionality

3.2.4. Emotional Responses

3.2.5. Revisit Intention

3.3. Sampling and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

4.2. Reliability and Validity

4.2.1. Reliability Analysis Results

4.2.2. Validity Analysis Results

4.2.3. Correlation Analysis Results

4.3. Verification of Research Hypothesis

4.3.1. Verification of Hypotheses H1-1, H1-2, and H1-3

4.3.2. Verification of Hypotheses H2-1, H2-2, and H2-3

4.3.3. Verification of Hypothesis H3

5. Conclusions

5.1. Study Summary

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managirial/Practical Implications

5.4. Study Limiations and Future Study Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hopkins, C.D.; Grove, S.J.; Raymond, M.A.; LaForge, M.C. Designing the E-Servicescape: Implications for Online Retailers. J. Internet Commer. 2009, 8, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankovic, A.C.; Benazic, D. The Perception of E-Servicescape and Its Influence on Perceived E-Shopping Value and Customer Loyalty. Online Inf. Rev. 2008, 42, 1124–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the Effects of Quality, Value, and Customer Satisfaction on Consumer Behavioral Intentions in Service Environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Pu, B.; Sang, W. How Travel Live Streaming Servicescape Affects Users’ Travel Intention: Evidence from Structural Equation Model and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N.; Asiah Abdullah, N. The Effect of Perceived Service Quality Dimensions on Customer Satisfaction, Trust, and Loyalty in E-Commerce Settings: A Cross Cultural Analysis. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2010, 22, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.D.; Vu, Q.H. Inspecting the Relationship among E-service quality, E-trust, E-customer Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions of Online Shopping Customers. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2019, 24, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Ryu, S.; Han, I. The Impact of the Online and Offline Features on the User Acceptance of Internet Shopping Malls. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2004, 3, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.L.; Hantula, D.A. Pricing Effects on Foraging in a Simulated Internet Shopping Mall. J. Econ. Psychol. 2003, 24, 653–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Srivastava, S.; Mishra, N. Impact of E-Servicescape on Hotel Booking Intention: Examining the Moderating Role of COVID-19. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2023, 18, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermantoro, M. E-Servicescape Analysis and its Effect on Perceived Value and Loyalty on E-Commerce Online Shopping Sites in Yogyakarta. Int. J. Bus. Ecosyst. Strategy 2022, 4, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Y.; Quyen, P.T.P.; Rivas, A.A.A. How E-Servicescapes Affect Customer Online Shopping Intention: The Moderating Effects of Gender and Online Purchasing Experience. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2017, 15, 689–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.P.; Chong, S.C.; Ismail, H.B.; Tong, D.Y.K. An Explorative Study of Shopper-Based Salient E-Servicescape Attributes: A Means-End Chain Approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Goode, M.M. Online Servicescapes, Trust, and Purchase Intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, A.S.; Hanny, H.; Hernández-García, Á.; Prasetya, P. ‘Stimuli Are All Around’—The Influence of Offline and Online Servicescapes in Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 524–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardiansyahmiraja, B.; Andajani, E.; Putra, A. Effects of E-Servicescape Dimensions on Online Food Delivery Services’ Purchase Intention. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. Publ. Online 2023, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampani, N.; Jhamb, D. Uncovering the Dimensions of Servicescape Using Mixed Method Approach—A Study of Beauty Salons. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 1247–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Massiah, C. An Expanded Servicescape Perspective. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loiacono, E.; Watson, R.; Goodhue, D. WebQual: A Measure of Website Quality. Mark. Theory Appl. 2002, 13, 432–438. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Lee, P.; Shin, C.H. Effects of Servicescapes on Interaction Quality, Service Quality, and Behavioral Intention in a Healthcare Setting. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, M. An Empirical Study of Business Processes across Internet-Based Electronic Marketplaces: A Supply-Chain-Management Perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2004, 10, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.H. Effects of Servicescape on Perceived Service Quality, Satisfaction and Behavioral Outcomes in Public Service Facilities. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2014, 13, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Mandal, S. E-Servicescape in Service: Theoretical Underpinnings and Emerging Market Implications. In Services Marketing Issues in Emerging Economies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Boukabiya, A.; Outtaj, B. The Impact of E-Servicescape on the Flow and Purchase Intention of Online Consumers: Quantitative Analysis of B to C E-Commerce Stores in Morocco. Int. J. Account. Financ. Audit. Manag. Econ. 2021, 2, 200–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kövecses, Z. Emotion Concepts; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K.S. Emotion and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niedenthal, P.M.; Halberstadt, J.B.; Innes-Ker, Å.H. Emotional Response Categorization. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. A Verbal Measure of Information Rate for Studies in Environmental Psychology. Environ. Behav. 1974, 6, 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Li, Z.; Mou, J.; Liu, X. Effects of Flow on Young Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention: A Study of E-Servicescape in Hotel Booking Context. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2017, 17, 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Mahara, T. Exploring the Role of E-Servicescape Dimensions on Customer Online Shopping: A Stimulus-Organism-Response Paradigm. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2020, 18, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Chon, K.; Ro, Y. Antecedents of Revisit intention. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Kumaravelu, J.; Goh, Y.-N.; Dara Singh, K.S. Understanding the Intention to Revisit a Destination by Expanding the theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Span. J. Mark-ESIC 2021, 25, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.A. Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R. The Effect of Online Experience on Revisit Intention Mediated with Offline Experience and Brand Equity. Adv. Econ. Manag. Res. 2019, 143, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Viet, B.; Dang, H.P.; Nguyen, H.H. Revisit Intention and Satisfaction: The Role of Destination Image, Perceived Risk, and Cultural Contact. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1796249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Feng, R. Temporal Destination Revisit Intention: The Effects of Novelty Seeking and Satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.; Shin, H.; Lee, Y.; Lee, C.W. Relationship among CSR Initiatives and Financial and Non-Financial Corporate Performance in the Ecuadorian Banking Environment. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.I.; Chung, K.H.; Oh, J.S.; Lee, C.W. The Effect of Site Quality on Repurchase Intention in Internet Shopping through Mediating Variables: The Case of University Students in South Korea. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Song, J.; Ma, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, S.; Chen, G.L. A Study of Cross-Border E-Commerce Research Trends: Based on Knowledge Mapping and Literature Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1009216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Benyoucef, M. From E-Commerce to Social Commerce: A Close Look at Design Features. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Chong, A.Y.-L. Predicting the Antecedents of Trust in Social Commerce—A Hybrid Structural Equation Modeling with Neural Network Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Peak, D.; Prybutok, V.R.; Xu, C. The Effect of Product Aesthetics Information on Website Appeal in Online Shopping. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2017, 8, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albshaier, L.; Almarri, S.; Rahman, H. A Review of Blockchain’s Role in E-Commerce Transactions: Open Challenges, and Future Research Directions. Computers 2024, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, T. Understanding Purchase Intention in O2O E-Commerce: The Effects of Trust Transfer and Online Contents. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situmorang, W.R.; Rini, E.S.; Sembiring, B.K.F. The Effect of Social Media, Servicescape and Customer Experience on Revisit Intention with the Visitor Satisfaction as an Intervening Variables in the Tree House on Tourism Habitat Pamah Semelir Langkat Regency. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2020, 7, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulkarem, A.; Hou, W. The Impact of Organizational Context on the Levels of Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption in Chinese SMEs: The Moderating Role of Environmental Context. J. theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2732–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y.; Mattila, A.S. Restaurant Servicescape, Service Encounter, and Perceived Congruency on Customers’ Emotions and Satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 819–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.Y. Effects of Visual Servicescape Aesthetics Comprehension and Appreciation on Consumer Experience. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 692–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, M. Effects of E-Servicescape on Consumers’ Flow Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2012, 3, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, A.; Pyun, K. How Do Customers Respond to the Hotel Servicescape? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B.; Bilgihan, A.; Ye, B.H.; Buonincontri, P.; Okumus, F. The Impact of Servicescape on Hedonic Value and Behavioral Intentions: The Importance of Previous Experience. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 72, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, T.; Zeki, S. A Neurobiological Enquiry into the Origins of Our Experience of the Sublime and Beautiful. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świątek, A.H.; Szcześniak, M.; Stempień, M.; Wojtkowiak, K.; Chmiel, M. The Mediating Effect of the Need for Cognition between Aesthetic Experiences and Aesthetic Competence in Art. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marković, S. Components of Aesthetic Experience: Aesthetic Fascination, Aesthetic Appraisal, and Aesthetic Emotion. i-Perception 2012, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, T.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y. How Does Urban Green Space Impact Residents’ Mental Health: A Literature Review of Mediators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Amegbor, P.M.; Sigsgaard, T.; Sabel, C.E. Assessing the Association between Urban Features and Human Physiological Stress Response Using Wearable Sensors in Different Urban Contexts. Health Place 2022, 78, 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Li, J.; Jia, C.; Liao, J.; Chen, K.; Huang, R. Neural Correlates of Transitive Inference: An SDM Meta-Analysis on 32 fMRI Studies. NeuroImage 2022, 258, 119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanucci, J.K. Emotional High: Emotion and the Perception of Spatial Layout. In Social Psychology of Visual Perception; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Makhbul, Z.M. Workplace Environment Towards Emotional Health. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, H.J.; Ni, J.J.; Chen, H.H. Relationship between E-Servicescape and Purchase Intention among Heavy and Light Internet Users. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlena, W.J.; Holbrook, M.B. The Varieties of Consumption Experience: Comparing Two Typologies of Emotion in Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, C.W. Servicescape Effect on Customer Emotion, Customer Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention in Logistics and Distribution Industries. Internet E-Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Shaouf, A.; Lü, K.; Li, X. The Effect of Web Advertising Visual Design on Online Purchase Intention: An Examination Across Gender. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robins, D.; Holmes, J. Aesthetics and Credibility in Web Site Design. Inf. Process. Manag. 2008, 44, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumah, E.P.; Hurriyati, R.; Disman, D.; Gaffar, V. Determining Revisit Intention: The Role of Virtual Reality Experience, Travel Motivation, Travel Constraint and Destination Image. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 28, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, S.M. The Effect of E-Servicescape, Website Trust and Perceived Value on Consumer Online Booking Intentions: The Moderating Role of Online Booking Experience. Int. Bus. Res. 2021, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohijoki, A.M.; Koistinen, K. The Effect of the Physical Environment on Consumers’ Perceptions: A Review of the Retailing Research on External Shopping Environment. Archit. Urban Plan. 2018, 14, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneja, S.; Hussain, S.; Melewar, T.C.; Foroudi, P. The Effects of Physical Environment Design on the Dimensions of Emotional Well-Being: A Qualitative Study from the Perspective of Design and Retail Managers. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2022, 25, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, K.; Johansson, U. An Exploration of Consumers’ Experiences in Physical stores: Comparing Consumers’ and Retailers’ Perspectives in Past and Present Time. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. New or repeat customers: How Does Physical Environment Influence their Restaurant Experience? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. The Impact of Nostalgia Triggers on Emotional Responses and Revisit Intentions in Luxury Restaurants: The Moderating Role of Hiatus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.; Bloch, P.H.; Ridgway, N.M. Shopping Motives, Emotional States, and Retail Outcomes. Environ. Retail. 2002, 21, 408–427. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, L.; Deswindi, L. Assessing the Effects of E-Servicescape on Customer Intention: A Study on the Hospital Websites in South Jakarta. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 169, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, G.A.; Strutton, D. Comparing email and SNS users: Investigating E-Servicescape, Customer Reviews, Trust, Loyalty and E-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergura, D.T.; Luceri, B. Product Packaging and Consumers’ Emotional Response. Does Spatial Representation Influence Product Evaluation and Choice? J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.T.; Park, C.H.; Kim, J.H. Examination of User Emotions and Task Performance in Indoor Space Design Using Mixed-Reality. Buildings 2023, 13, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Han, X.; Jung, T. Analysis of Spatial Perception and the Influencing Factors of Attractions in Southwest China’s Ethnic Minority Areas: The Case of Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Items | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| AES | The design of this shopping mall site is sophisticated. The design of this shopping mall site is beautiful. The design of this shopping mall site is excellent. The design colors of this shopping mall site are attractive. | [2,18,51,62] |

| SUR | The background music on this shopping mall site is excellent. The sound effects of this shopping mall site are excellent. The video presentation on this shopping mall site is excellent. The videos presented on this shopping mall site are vivid. | [15,17,20,75] |

| SPA | This shopping mall site is convenient to use. This shopping mall site has fast navigation. This shopping mall site is easy to search for information. This shopping mall site is easy to browse. | [2,17,19,76] |

| EMO | Happy while shopping at this mall site. Fulfilled while shopping at this shopping mall site. Comfortable while shopping at this mall site. Trustworthy while shopping on this shopping mall site. | [25,27,32,77] |

| REV | Like to use this shopping mall site again. Visit this shopping mall site again. Visit this shopping mall site often. | [1,34,37,72] |

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies | Percents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 53 | 35.3 |

| Female | 97 | 64.7 | |

| Age | 21–30 | 120 | 80.0 |

| 31–40 | 3020.0 | ||

| Education | Junior college degree or lower | 18 | 12.0 |

| College degree | 94 | 62.7 | |

| Graduate school degree or higher | 38 | 25.3 | |

| Monthly living expenes | USD 415 or less | 45 | 30.0 |

| USD 416–690 | 41 | 27.3 | |

| USD 691–970 | 27 | 18.0 | |

| USD 971–1380 | 21 | 14.0 | |

| USD 1381 or higher | 16 | 10.7 | |

| Frequently purchased products | Electronic products | 96 | 64.0 |

| Cosmetics | 6 | 4.0 | |

| Clothing | 3 | 2.0 | |

| Necessities | 37 | 24.7 | |

| Others | 8 | 5.3 | |

| Average spending | USD 27 or less | 51 | 34.0 |

| USD 28–83 | 66 | 44.0 | |

| USD 84–138 | 12 | 8.0 | |

| USD 139 or higher | 21 | 14.0 |

| Variables | Items | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha | Overall Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AES | AES1 | 0.938 | 0.936 | 0.949 |

| AES2 | ||||

| AES3 | ||||

| AES4 | ||||

| SUR | SUR1 | 0.921 | 0.919 | |

| SUR2 | ||||

| SUR3 | ||||

| SUR4 | ||||

| SPA | SPA1 | 0.926 | 0.925 | |

| SPA2 | ||||

| SPA3 | ||||

| SPA4 | ||||

| EMO | EMO1 | 0.918 | 0.917 | |

| EMO2 | ||||

| EMO3 | ||||

| EMO4 | ||||

| REV | REV1 | 0.900 | 0.884 | |

| REV2 | ||||

| REV3 |

| Variables | Items | Unstandardized λ | SE | CR | Standardized λ | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AES | AES1 | 1 | 0.859 | 0.792 | ||

| AES2 | 0.992 | 0.061 | 16.361 *** | 0.934 | ||

| AES3 | 1.035 | 0.065 | 15.821 *** | 0.918 | ||

| AES4 | 0.915 | 0.068 | 13.544 *** | 0.846 | ||

| SUR | SUR1 | 1 | 0.853 | 0.744 | ||

| SUR2 | 1.011 | 0.070 | 14.440 *** | 0.895 | ||

| SUR3 | 1.119 | 0.084 | 13.356 *** | 0.855 | ||

| SUR4 | 1.098 | 0.084 | 13.117 *** | 0.846 | ||

| SPA | SPA1 | 1 | 0.855 | 0.759 | ||

| SPA2 | 1.030 | 0.074 | 13.848 *** | 0.865 | ||

| SPA3 | 1.072 | 0.070 | 15.424 *** | 0.918 | ||

| SPA4 | 1.055 | 0.079 | 13.280 *** | 0.845 | ||

| EMO | EMO1 | 1 | 0.800 | 0.736 | ||

| EMO2 | 1.074 | 0.090 | 11.915 *** | 0.845 | ||

| EMO3 | 1.207 | 0.095 | 12.690 *** | 0.883 | ||

| EMO4 | 1.266 | 0.097 | 13.030 *** | 0.900 | ||

| REV | REV1 | 1.000 | 0.918 | 0.749 | ||

| REV2 | 1.021 | 0.072 | 12.278 *** | 0.880 | ||

| REV3 | 1.160 | 0.090 | 12.903 *** | 0.795 |

| Variables | AES | SUR | SPA | EMO | REV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AES | 0.890 | ||||

| SUR | 0.634 *** | 0.863 | |||

| SPA | 0.486 *** | 0.569 *** | 0.871 | ||

| EMO | 0.425 *** | 0.526 *** | 0.744 *** | 0.858 | |

| REV | 0.298 *** | 0.430 *** | 0.632 *** | 0.770 *** | 0.865 |

| Variables | AES | SUR | SPA | EMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUR | 0.682 | |||

| SPA | 0.521 | 0.620 | ||

| EMO | 0.457 | 0.575 | 0.807 | |

| REV | 0.322 | 0.477 | 0.699 | 0.850 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index | Recommended Threshold | Model Fit Results |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | ≤3 | 2.154 |

| GFI | ≥0.9 | 0.830 |

| RMR | ≤0.05 | 0.027 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.088 |

| NFI | ≥0.9 | 0.893 |

| TLI | ≥0.9 | 0.927 |

| IFI | ≥0.9 | 0.940 |

| CFI | ≥0.9 | 0.939 |

| Hypotheses | Path | Standardized Coefficent | SE | t | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | AES | → | EMO | −0.016 | 0.070 | −0.228 | Not supported |

| H1-2 | SUR | → | EMO | 0.127 | 0.089 | 1.437 | Not supported |

| H1-3 | SPA | → | EMO | 0.681 | 0.091 | 7.480 *** | Supported |

| H2-1 | AES | → | REV | −0.113 | 0.066 | −1.703 * | Supported |

| H2-2 | SUR | → | REV | 0.042 | 0.084 | 0.497 | Not supported |

| H2-3 | SPA | → | REV | 0.073 | 0.105 | 0.695 | Not supported |

| H3 | EMO | → | REV | 0.825 | 0.119 | 6.958 *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.B.; Lee, C.W. Effect of E-Servicescape on Emotional Response and Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2030-2050. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030099

Li Z, Tulcanaza-Prieto AB, Lee CW. Effect of E-Servicescape on Emotional Response and Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(3):2030-2050. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030099

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zeyu, Ana Belén Tulcanaza-Prieto, and Chang Won Lee. 2024. "Effect of E-Servicescape on Emotional Response and Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 3: 2030-2050. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030099

APA StyleLi, Z., Tulcanaza-Prieto, A. B., & Lee, C. W. (2024). Effect of E-Servicescape on Emotional Response and Revisit Intention in an Internet Shopping Mall. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(3), 2030-2050. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030099