Towards Frugal Innovation Capability in Emerging Markets within the Digitalization Epoch: Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity

Abstract

1. Introduction

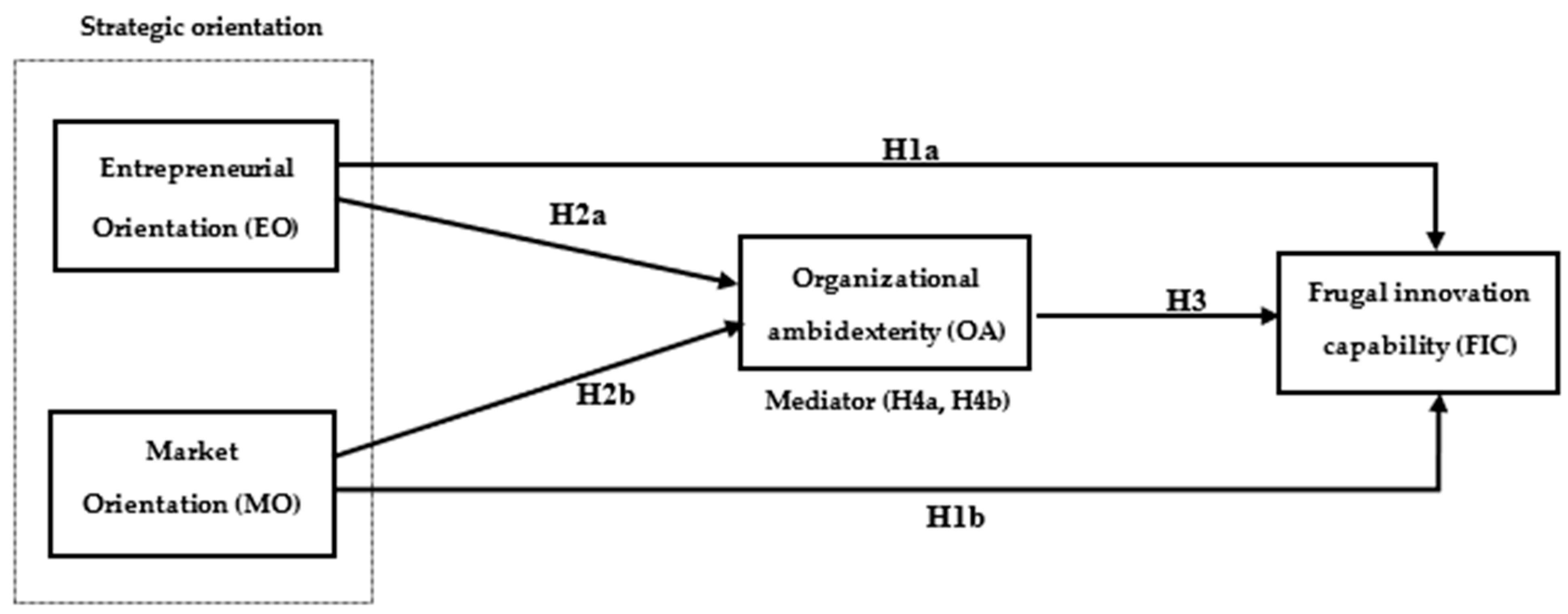

2. Literature Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Frugal Innovation

2.2. Strategic Orientation

2.2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation

2.2.2. Market Orientation

2.3. Organizational Ambidexterity

2.4. Strategic Orientation and Frugal Innovation Capability

2.5. Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity

2.6. Organizational Ambidexterity and Frugal Innovation Capability

2.7. Mediating the Effect of Organizational Ambidexterity

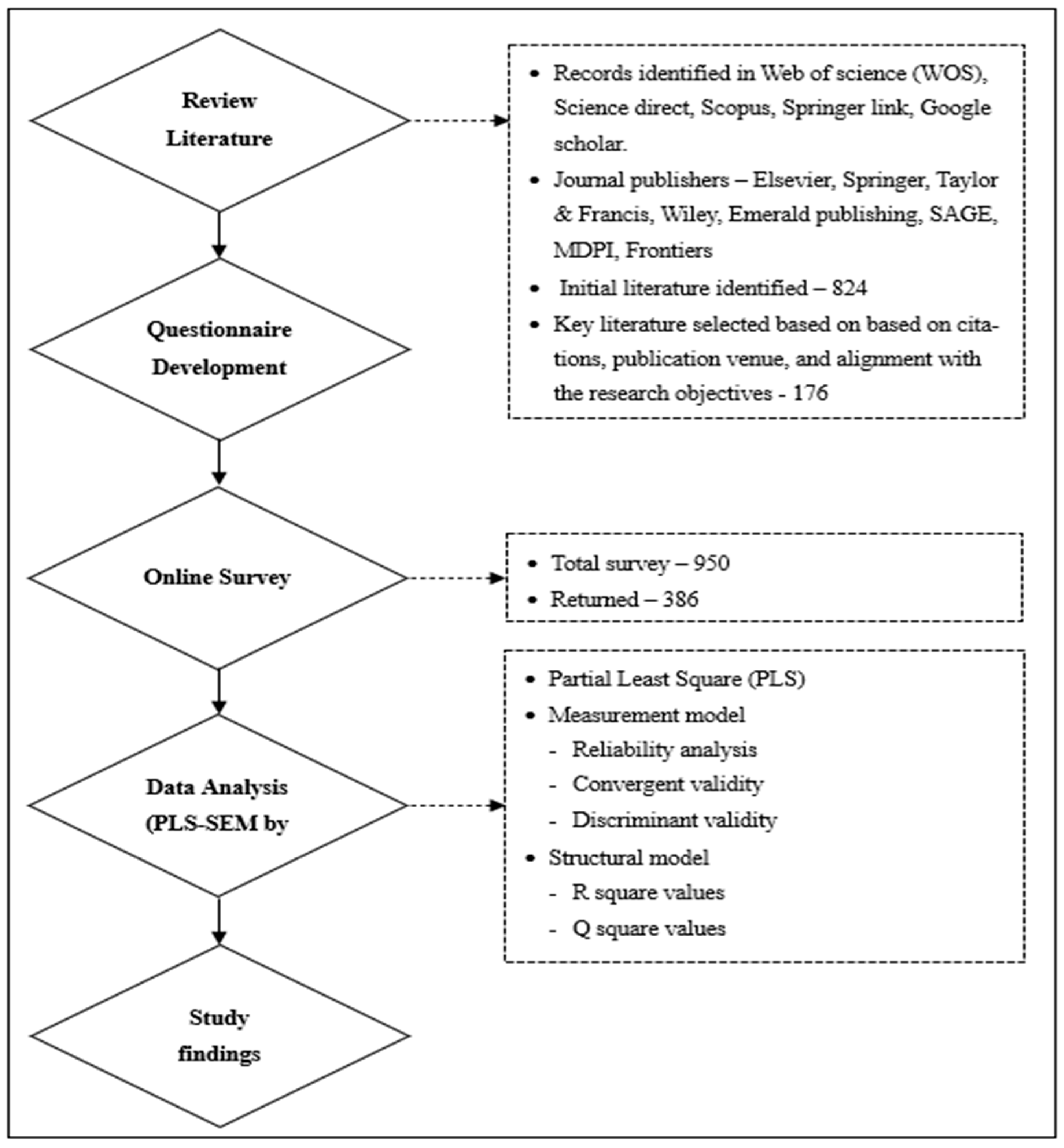

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection Method

3.2. Sampling Method and Sample Size Determination

3.3. Measurement of Constructs

3.3.1. Strategic Orientation

3.3.2. Organizational Ambidexterity

3.3.3. Frugal Innovation Capability

3.4. Model Specification and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

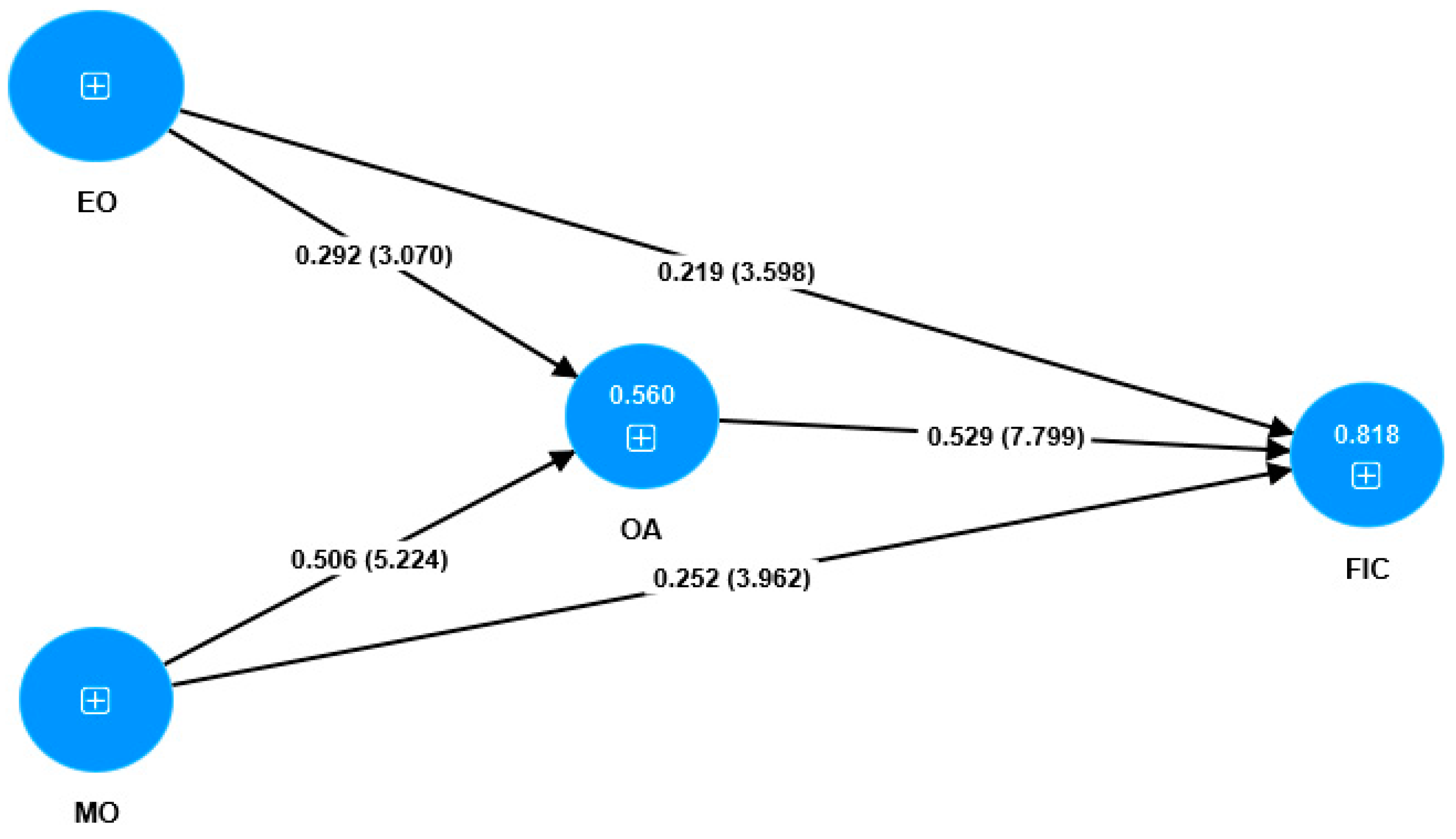

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Mediation Role of Organizational Ambidexterity

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

6. Implications and Avenues for Future Research

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Code | Items | Sources |

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | INN1 | In the past three years, our company introduced and encouraged novel ideas, products or services. | [88] |

| INN2 | In general, our company favor a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations. | ||

| INN3 | in our company changes in product or service lines have usually been quite dramatic. | ||

| RISK1 | Our company tends to strongly favor high-risk projects (with chances of very high returns). | ||

| RISK2 | Owing to the nature of the environment, our company favors bold and wide-ranging actions to achieve its fixed objectives. | ||

| RISK3 | When confronted with decisions involving uncertainty, our company typically adopts a bold posture in order to maximize the probability of exploiting opportunities. | ||

| PRO1 | In general, our company have a strong tendency to be ahead of others in introducing novel ideas or products. | ||

| PRO2 | In dealing with competitors, our company is very often the first business to introduce new products/services, administrative techniques or operating technologies. | ||

| PRO3 | In dealing with competitors, our company typically initiate actions that competitors respond to. | ||

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Market orientation | CUSTO1 | Our company objectives are driven primarily by customer satisfaction | [94,159,160] |

| CUSTO2 | We constantly monitor our level of commitment and orientation to serving customers’ needs | ||

| CUSTO3 | Our strategy for competitive advantage is based on our understanding of customers’ needs | ||

| CUSTO4 | Our company strategies are driven by our beliefs about how we can create greater value for customers | ||

| CUSTO5 | We measure customer satisfaction systematically and frequently | ||

| CUSTO6 | We give close attention to after-sales service | ||

| COMPO1 | Our salespeople regularly share information within our company concerning competitors’ strategies | ||

| COMPO2 | We rapidly respond to competitive actions that threaten us | ||

| COMPO3 | We regularly discuss competitors’ strengths and strategies | ||

| COMPO4 | We target customers where we have an opportunity for competitive advantage | ||

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Organizational ambidexterity | AL1 | The management systems of our company work coherently to support the overall objectives of the company. | [100] |

| AL2 | Employees of our company work toward the same goals because our management systems avoid conflicting objectives | ||

| AL3 | The management systems of our company prevent wastage of resources on unproductive activities. | ||

| AD1 | The management systems of our company encourage employees to challenge outmoded traditions/practices | ||

| AD2 | The management systems of our company are flexible enough to allow quick response to changes in our market. | ||

| AD3 | The management systems of our company evolve rapidly in response to shifts in our business priorities. | ||

| Indicate to which extent did your company assigned great important in the development of products/services | |||

| Frugal innovation capability | CF1 | Core functionality of the product rather than additional functionality | [164] |

| CF2 | Ease of product use | ||

| CF3 | The question of the durability of the product (does not spoil easily) the durability of the product | ||

| SCR1 | Solutions that offer “good-value” products | ||

| SCR2 | Cost reduction in the operational process | ||

| SCR3 | Savings of organizational resources in the operational process | ||

| SCR4 | Rearrangement of organizational resources in the operational process | ||

| SSE1 | Efficient and effective solutions to customers’ social/environmental needs | ||

| SSE2 | Environmental sustainability in the operational process | ||

| SSE3 | Partnerships with local companies in the operational process | ||

References

- Immelt, J.R.; Govindarajan, V.; Trimble, C. How GE is disrupting itself. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K. The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty through Profits, Revised and Updated 5th Anniversary ed.; Wharton School Pub: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-700927-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeschky, M.; Widenmayer, B.; Gassmann, O. Frugal Innovation in Emerging Markets. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Hart, S.L. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: Beyond the transnational model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Väisänen, J.-M. Digital technologies catalyzing business model innovation for circular economy—Multiple case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, S.D.; Leon, F.M.; Widyastuti, S.; Brabo, N.A.; Putra, A.H.P.K. Antecedents and Consequences of Innovation and Business Strategy on Performance and Competitive Advantage of SMEs. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Yang, Y. Innovation and competition with human capital input. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 1779–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K.G. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution; Harvard Business Press: Cambrige, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4221-5786-2. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y.; Sun, L. Firm Growth via Mergers and Acquisitions in China; Fisher College of Business, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Khoury, T.A. Unbundling the Institution-Based View of International Business Strategy. In The Oxford Handbook of International Business; Rugman, A.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 256–268. ISBN 978-0-19-923425-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-13-030794-1. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1959; ISBN 978-0-19-957384-4. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W. Institutional Transitions and Strategic Choices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Yim, C.K.; Tse, D.K. The Effects of Strategic Orientations on Technology- and Market-Based Breakthrough Innovations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivdas, A.; Barpanda, S.; Sivakumar, S.; Bishu, R. Frugal innovation capabilities: Conceptualization and measurement. Prometheus 2021, 37, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, W.; Peteraf, M.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.; Winter, S.G. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4051-8206-5. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.A.; Harvey, M.G. A Resource Perspective of Global Dynamic Capabilities. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How strategic orientations influence the building of dynamic capability in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How does strategic orientation matter in Chinese firms? Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2007, 24, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Xuereb, J.-M. Strategic Orientation of the Firm and New Product Performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Moderators. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Lew, Y.K.; Puthusserry, P.; Czinkota, M. Strategic ambidexterity and its performance implications for emerging economies multinationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wood, G.; Chen, X.; Meyer, M.; Liu, Z. Strategic ambidexterity and innovation in Chinese multinational vs. indigenous firms: The role of managerial capability. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Zimmermann, A.; Raisch, S. How Do Firms Adapt to Discontinuous Change? Bridging the Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity Perspectives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, J.-E.; Jonsson, A. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability in the globalization of the multinational business enterprise (MBE): Case studies of AB Volvo and IKEA. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadiuk, S.; Luz, A.R.S.; Kretschmer, C. Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity: How are These Concepts Related? Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2018, 22, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-119-71330-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Voss, Z.G. Strategic Orientation and Firm Performance in an Artistic Environment. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J.; Braojos, J. IT-enabled knowledge ambidexterity and innovation performance in small U.S. firms: The moderator role of social media capability. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, R. Strategic orientation, business model innovation and corporate performance—Evidence from construction industry. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 971654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Knight, G.A. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation: Conception, development, diffusion, and outcome. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, R.; Gurtner, S.; Griffin, A. Towards an adaptive framework of low-end innovation capability—A systematic review and multiple case study analysis. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 770–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Arnold, M.; Bendul, J.C. Business models for sustainable innovation—An empirical analysis of frugal products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S133–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grawe, S.J.; Chen, H.; Daugherty, P.J. The relationship between strategic orientation, service innovation, and performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 282–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar, H.; Nart, S.; Bingöl, D. The Effects of Strategic Orientations on Innovation Capabilities and Market Performance: The Case of ASEM. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Han, S.; Ito, H. Capability building through innovation for unserved lower end mega markets. Technovation 2013, 33, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URT Small and Medium Enterprise Development Policy 2003. Available online: https://www.viwanda.go.tz/uploads/documents/en-1618820071-1455890063-SME-Development-Policy.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Mungaya, M.; Mbwambo, A.H.; Tripathi, S.K. Study of tax system impact on the growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs): With reference to Shinyanga Municipality, Tanzania. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 2012, 2, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mashenene, R.G. Socio-cultural determinants of entrepreneurial capabilities among the Chagga and Sukuma small and medium enterprises in Tanzania. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tundui, H.P. Gender and Small Business Growth in Tanzania: The Role of Habitus; University of Groningen, SOM Research School: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mutambala, M. Sources and Constraints to Technological Innovation in Tanzania: A Case Study of the Wood Furniture Industry in Dar es Salaam; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrucken, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, A.C.; Gomes, G.; Borini, F.M. Exploring the antecedents of frugal innovation and operational performance: The role of organizational learning capability and entrepreneurial orientation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1704–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.C.; Gomes, G.; Borini, F.M.; Bernardes, R.C. Frugal innovation and operational performance: The role of organizational learning capability. RAUSP Manag. J. 2023, 58, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W. Innovating with Limited Resources: The Antecedents and Consequences of Frugal Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.L.; Borini, F.M.; Oliveira, M.d.M.; Rossetto, D.E.; Bernardes, R.C. Bricolage as capability for frugal innovation in emerging markets in times of crisis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 25, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterhalter, S.; Zeschky, M.B.; Neumann, L.; Gassmann, O. Business Models for Frugal Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Case of the Medical Device and Laboratory Equipment Industry. Technovation 2017, 66–67, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation: A review and research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dost, M.; Pahi, M.H.; Magsi, H.B.; Umrani, W.A. Effects of sources of knowledge on frugal innovation: Moderating role of environmental turbulence. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1245–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.C. The science underlying frugal innovations should not be frugal. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 180421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyrauch, T.; Herstatt, C. What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria. J. Frugal Innov. 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, A.; Michelini, L.; Martignoni, G. Frugal approach to innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R. A conceptual model of frugal innovation: Is environmental munificence a missing link? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2017, 9, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kalogerakis, K.; Herstatt, C. Frugal Innovations in the Mirror of Scholarly Discourse: Tracing Theoretical Basis and Antecedents. In R&D Management Conference, Cambridge, UK. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Frugal%20Innovations%20in%20the%20Mirror%20of%20Scholarly%20Discourse%3A%20Tracing%20Theoretical%20Basis%20and%20Antecedents&author=R.%20Tiwari&publication_year=2016 (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Frugal and reverse innovation—Literature overview and case study insights from a German MNC in India and China. In Proceedings of the Technology and Innovation 2012 18th International ICE Conference on Engineering, Munich, Germany, 18–20 June 2012; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, A.; Ivens, B. Do Frugal and Reverse Innovation Foster Sustainability? Introduction of a Conceptual Framework. J. Technol. Manag. Grow. Econ. 2013, 4, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Y.A. What is Frugal, What is Innovation? Towards a Theory of Frugal Innovation. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, 2012, 10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D. Design of customised products and manufacturing networks: Towards frugal innovation. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 31, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, M.; Singh, S.K. Innovation capability. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2005, 17, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeven, M. Innovation in an Uncertain Institutional Environment: Private Software Entrepreneurs in Hangzhou, China; Erasmus University Rotterdam, Erasmus Research Institute of Management: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 978-90-5892-202-1. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Shenhar, A. Adapting Your Technological Base: The Organizational Challenge. 1990. Available online: https://faculty.marshall.usc.edu/Paul-Adler/research/TechBase%20SMR.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Asakawa, K.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Un, C. Frugality-based advantage. Long Range Plann. 2019, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterhoff, M.; Boehler, C. Simple, Simpler, Best: Frugal Innovation in the Engineered Products and High Tech Industry. Roland Berg. Strategy Consult. 2014. Available online: https://www.rolandberger.com/publications/publication_pdf/roland_berger_tab_frugal_products_e_20150107.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting High-Impact Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Some Suggested Guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches to Understanding the Interaction between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientations: Orientations in Management Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Whittington, R.; Angwin, D.; Regnèr, P.; Scholes, K. Exploring Strategy; Pearson: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-292-00701-4. [Google Scholar]

- O’Regan, N.; Ghobadian, A. Innovation in SMEs: The impact of strategic orientation and environmental perceptions. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2005, 54, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franczak, J.; Weinzimmer, L.; Michel, E. An empirical examination of strategic orientation and SME performance. Small Bus. Inst. Natl. Proc. 2009, 33, 68–325. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, C.; Hughes, M. The relative impact of culture, strategic orientation and capability on new service development performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. Arnold the Relationship Between Marketing Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.; Anokhin, S.; Kretinin, A.; Frishammar, J. The dark side of the entrepreneurial orientation and market orientation interplay: A new product development perspective. Int. Small Bus. J. 2015, 33, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Revisited: A Reflection on EO Research and Some Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1983, 35, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, G.K.; Gupta, M.C.; Cheng, T.C.E. The effects of strategic orientation on operational ambidexterity: A study of indian SMEs in the industry 4.0 era. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 220, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.; Anokhin, S.A. The joint impact of entrepreneurial orientation and market orientation in new product development: Studying firm and environmental contingencies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. The Measurement of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Archetypes of Strategy Formulation. Manag. Sci. 1978, 24, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.S.; Kreiser, P.M.; Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Eshima, Y. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Zhang, D.; Bruning, E. Personal characteristics and strategic orientation: Entrepreneurs in Canadian manufacturing companies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2011, 17, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, A.R.A. The mediating role of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and technological innovation capabilities. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.; Sinkula, J. The Complementary Effect of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Innovation Success and Profitability. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 47, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Laghouag, A.A.; Ali Sahli, A.; Belaid, F. Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Innovation Capability: The Mediating Role of Absorptive Capability and Organizational Learning Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyo, H.; Ayuni, S. Competitive advantages of SMEs: The roles of innovation capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and social capital. Contad. Adm. 2019, 65, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, A.K.; Jaworski, B.J. Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpandé, R.; Farley, J.U. Organizational culture, market orientation, innovativeness, and firm performance: An international research odyssey. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakapour, S.; Morgan, T.; Parsinejad, S.; Wieland, A. Antecedents of corporate entrepreneurship in Iran: The role of strategic orientation and opportunity recognition. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2016, 28, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jing, L. Strategic orientation and performance of new ventures: Empirical studies based on entrepreneurial activities in China. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 989–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Al-Azad, M.d.S.; Mohiuddin, M.; Reza, M.N.H. Strategic orientations, organizational ambidexterity, and sustainable competitive advantage: Mediating role of industry 4.0 readiness in emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 401, 136765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Terjesen, S.; Li, D. Enhancing effects of manufacturing flexibility through operational absorptive capacity and operational ambidexterity. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurksiene, L.; Pundziene, A. The relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.; Miorando, R.; Caiado, R.; Nascimento, D.; Portioli Staudacher, A. The mediating effect of employees’ involvement on the relationship between Industry 4.0 and operational performance improvement. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghantous, N.; Alnawas, I. The differential and synergistic effects of market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on hotel ambidexterity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpkan, L.; Şanal, M.; Ayden, Y. üksel Market Orientation, Ambidexterity and Performance Outcomes. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 41, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Mani, V. Analyzing the mediating role of organizational ambidexterity and digital business transformation on industry 4.0 capabilities and sustainable supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Stöckmann, C.; Covin, J.G. The status quo of research on entrepreneurial orientation: Conversational landmarks and theoretical scaffolding. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyabo, K.; Isaga, N. Entrepreneurial orientation, competitive advantage, and SMEs’ performance: Application of firm growth and personal wealth measures. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Nakara, W.A.; Gharbi, S.; Bahri, C. The Relationship between Organizational Culture and Small-firm Performance: Entrepreneurial Orientation as Mediator. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miller, D. International Entrepreneurial Orientation: Conceptual Considerations, Research Themes, Measurement Issues, and Future Research Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 11–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Gupta, V.K.; Mousa, F.-T. Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 357–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Organizational Learning Capability and Innovation Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawarna, D.; Rouse, J.; Kitching, J. Entrepreneur motivations and life course. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Neira, C.; Arias, M.J.F.; Lindman, M.T. Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Proclivity: Antecedents of Innovation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Drakopoulou Dodd, S.; Jack, S.L. Entrepreneurship as connecting: Some implications for theorising and practice. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Morgan, R.E. Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Weiss, M.M.; Calantone, R. Determinants of new product performance: A review and meta-analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1994, 11, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, G.; Yilmaz, C. Innovative capability, innovation strategy and market orientation: An empirical analysis in turkish software industry. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2008, 12, 69–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Kim, N.; Srivastava, R.K. Market Orientation and Organizational Performance: Is Innovation a Missing Link? J. Mark. 1998, 62, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Ko, A. An Empirical Investigation of the Effect of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurship Orientation Alignment on Product Innovation. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Omar, N.A. Exploring the effect of Internet marketing orientation, Learning Orientation and Market Orientation on innovativeness and performance: SME (exporters) perspectives. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 14, S257–S278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.; Kim, K. The role of learning capability in market-oriented firms in the context of open innovation-based technology acquisition: Empirical evidence from the Korean manufacturing sector. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2016, 70, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. An Exploratory Analysis of the Impact of Market Orientation on New Product Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1995, 12, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Su, J. How does market orientation affect product innovation in China’s manufacturing industry: The contingent value of dynamic capabilities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Education Technology and Management Science, Nanjing, China, 8–9 June 2013; Atlantis Press: Nanjing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Posch, A.; Garaus, C. Boon or curse? A contingent view on the relationship between strategic planning and organizational ambidexterity. Long Range Plann. 2020, 53, 101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Organizational Ambidexterity, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and I-Deals: The Moderating Role of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.A.; Edgar, F.; Geare, A.; O’Kane, C. The interactive effects of entrepreneurial orientation and capability-based HRM on firm performance: The mediating role of innovation ambidexterity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 59, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J.; Wright, M.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Gilbert, B.A. Resource Orchestration to Create Competitive Advantage: Breadth, Depth, and Life Cycle Effects. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Krishna Erramilli, M.; Dev, C.S. Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.; Krumwiede, D. The role of service innovation in the market orientation—New service performance linkage. Technovation 2012, 32, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotteland, D.; Shock, J.; Sarin, S. Strategic orientations, marketing proactivity and firm market performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. Resolving the Capability–Rigidity Paradox in New Product Innovation. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-L.; Wong, P.-K. Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Kallinger, F.L.; Bican, P.M.; Brem, A.; Kailer, N. Organizational ambidexterity and competitive advantage: The role of strategic agility in the exploration-exploitation paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, G. Organizational Ambidexterity and Competitive Advantage: Toward A Research Model. Manag. Mark. Craiova 2014, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- van Lieshout, J.W.F.C.; van der Velden, J.M.; Blomme, R.J.; Peters, P. The interrelatedness of organizational ambidexterity, dynamic capabilities and open innovation: A conceptual model towards a competitive advantage. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 26, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, A.; Krishnan, T.N.; Upadhyayula, R.S.; Kumar, M. Finding the microfoundations of organizational ambidexterity—Demystifying the role of top management behavioural integration. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, J. International ambidexterity in firms’ innovation of multinational enterprises from emerging economies: An investigation of TMT attributes. Balt. J. Manag. 2020, 15, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Luan, R.; Wu, H.-H.; Zhu, W.; Pang, J. Ambidextrous balance and channel innovation ability in Chinese business circles: The mediating effect of knowledge inertia and guanxi inertia. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Pickernell, D.; Battisti, M.; Soetanto, D.; Huang, Q. When is entrepreneurial orientation beneficial for new product performance? The roles of ambidexterity and market turbulence. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 27, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofiani, D.; Indarti, N.; Lukito-Budi, A.S.; Manik, H.F.G.G. The dynamics between balanced and combined ambidextrous strategies: A paradoxical affair about the effect of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ performance. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 1262–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aren, S.; Şanal, M.; Alpkan, L.; Sezen, B.; Ayden, Y. Linking Market Orientation and Ambidexterity to Financial Returns with the Mediation of Innovative Performance. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2013, 15, 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Enkel, E.; Heil, S.; Hengstler, M.; Wirth, H. Exploratory and exploitative innovation: To what extent do the dimensions of individual level absorptive capacity contribute? Technovation 2017, 60–61, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Welie, M.J.; Truffer, B.; Gebauer, H. Innovation challenges of utilities in informal settlements: Combining a capabilities and regime perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 33, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapersonne, A.; Sanghavi, N.; De Mattos, C. Hybrid Strategy, ambidexterity and environment: Toward an integrated typology. Univers. J. Manag. 2015, 3, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelos Gómez, J.; Vargas Franco, D.; Romero Sánchez, G. The Outstanding Relevance of Frugal Innovation in the Manufacturing Sector of Emerging Economies|Revista Electrónica Gestión de las Personas y Tecnologías|EBSCOhost. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/doi:10.35588%2Fgpt.v16i48.6507?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:doi:10.35588%2Fgpt.v16i48.6507 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- ITA Tanzania—Manufacturing. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/tanzania-manufacturing (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Nyello, R.M.; Kalufya, N. Entrepreneurial Orientations and Business Financial Performance: The Case of Micro Businesses in Tanzania. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 9, 1263–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, N.G.; Blank, G.; Lee, R.M. The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85702-005-5. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-515309-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfie, H.J.; Bratchell, N.; Greenhoff, K.; Vallis, L.V. DESIGNS TO BALANCE THE EFFECT OF ORDER OF PRESENTATION AND FIRST-ORDER CARRY-OVER EFFECTS IN HALL TESTS. J. Sens. Stud. 1989, 4, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. IJeC 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Vij, S. Toward the measurement of market orientation: Scale development and validation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 45, 1275–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguaw, J.; A, J.; Diamantopoulos, A. Measuring Market Orientation: Some Evidence on Narver and Slater’s Three-Component Scale. J. Strateg. Mark. 1995, 3, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Girardi, A.; Lewandowska, A. A Cross-National Validation of the Narver and Slater Market Orientation Scale. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2006, 14, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.H.; Simsek, Z.; Ling, Y.; Veiga, J.F. Ambidexterity and Performance in Small-to Medium-Sized Firms: The Pivotal Role of Top Management Team Behavioral Integration. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 646–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.E.; Borini, F.M.; Bernardes, R.C.; Frankwick, G.L. Measuring frugal innovation capabilities: An initial scale proposition. Technovation 2023, 121, 102674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. “SmartPLS 4.” Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Predictive vs. Structural Modeling: PLS vs. ML. In Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 199–226. ISBN 978-3-642-52514-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Incorporated: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4833-7743-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0. [Google Scholar]

- Jr, J.F.H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4833-7739-1. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.; Rönkkö, M. Statistical Inference with PLSc Using Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 1001–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 587–632. ISBN 978-3-319-57411-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 1988; ISBN 978-1-134-74270-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Song, T.H.; Yoo, S. Paths to Success: How Do Market Orientation and Entrepreneurship Orientation Produce New Product Success? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, I.N.; Massie, J.D.D.; Tumewu, F.J. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Capability Towards Firm Performance in Small and Medium Enterprises (Case Study: Grilled Restaurants in Manado). J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribau, C.P.; Moreira, A.C.; Raposo, M. The role of exploitative and exploratory innovation in export performance: An analysis of plastics industry SMEs. Eur. J Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Parga-Montoya, N. How ICT usage affect frugal innovation in Mexican small firms. The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H. Market orientation and product innovation: The mediating role of technological capability. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1233–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didonet, S.R.; Simmons, G.; Díaz-Villavicencio, G.; Palmer, M. Market Orientation’s Boundary-Spanning Role to Support Innovation in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Carneiro, J.; Finchelstein, D.; Duran, P.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A.; Montoya, M.A.; Borda Reyes, A.; Fleury, M.T.L.; Newburry, W. Uncommoditizing strategies by emerging market firms. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, D.; Frasquet, M.; Calderon, H. The role of market orientation and innovation capability in export performance of small- and medium-sized enterprises: A Latin American perspective. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2022, 30, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Rauch, A.; Bausch, A. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Task Environment–Performance Relationship: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, A.; Skarmeas, D.; Saridakis, C. Entrepreneurial orientation pathways to performance: A fuzzy-set analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1319–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, P.S.; Bausch, A. How Do Transformational Leaders Promote Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation? Examining the Black Box through MASEM. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 687–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Liu, Z. Paths to success: An ambidexterity perspective on how responsive and proactive market orientations affect SMEs’ business performance. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 420–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity in Action: How Managers Explore and Exploit. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 53, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, R.; Safitri, N.; Khafian, N. Developing Innovation Capability of SME through Contextual Ambidexterity. Bisnis Birokrasi J. 2016, 22, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khawaldah, R.A.; Al-zoubi, W.K.; Alshaer, S.A.; Almarshad, M.N.; ALShalabi, F.S.; Altahrawi, M.H.; Al-hawary, S.I. Green supply chain management and competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. The mediating role of ambidextrous capability in learning orientation and new product performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C. Organizational ambidexterity, market orientation, and firm performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 33, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.; Al-Henzab, J.; Tarhini, A.; Obeidat, B.Y. The associations among market orientation, technology orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and organizational performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3117–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Prijadi, R.; Kusumastuti, R.D. Strategic orientations and firm performance: The role of information technology adoption capability. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prifti, R.; Alimehmeti, G. Market orientation, innovation, and firm performance—An analysis of Albanian firms. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.d.C.; Perin, M.G. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: An updated meta-analysis. RAUSP Manag. J. 2020, 55, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, Z. Frugal-based innovation model for sustainable development: Technological and market turbulence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, V.; Magnusson, M. A bibliometric map of intellectual communities in frugal innovation literature. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 68, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 243 | 62.95 |

| Female | 143 | 37.05 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Years of services in the current organization | ||

| 1 to 3 years | 113 | 29.27 |

| 4 to 6 years | 205 | 53.11 |

| More than 6 years | 68 | 17.62 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Designation | ||

| Owner/CEO/General Manager | 158 | 40.93 |

| Production/Operations Manager | 80 | 20.73 |

| Marketing Manager | 74 | 19.17 |

| Finance Manager | 39 | 10.1 |

| HR Manager | 35 | 9.07 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Firm sub-sector in manufacturing industry | ||

| Fashion (textile, footwear and apparel) | 125 | 32.38 |

| Food (food processing, alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, dairy products) | 133 | 34.46 |

| Furniture and fittings, plastic, chemical and metal products | 128 | 33.16 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Number of years since establishment | ||

| Below 5 | 110 | 28.5 |

| Between 5 to 10 | 176 | 45.6 |

| Above 10 | 100 | 25.91 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Firm location | ||

| Dar es Salaam city | 248 | 64.25 |

| Arusha city | 138 | 35.75 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | rho_A | Composite Reliability (CR) | (AVE) | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial orientation | EO1 | 0.835 | 0.942 | 0.944 | 0.951 | 0.684 | 2.703 |

| EO2 | 0.830 | 2.576 | |||||

| EO3 | 0.832 | 2.743 | |||||

| EO4 | 0.855 | 2.931 | |||||

| EO5 | 0.825 | 2.604 | |||||

| EO6 | 0.804 | 2.457 | |||||

| EO7 | 0.815 | 2.485 | |||||

| EO8 | 0.842 | 2.804 | |||||

| EO9 | 0.804 | 2.371 | |||||

| Market orientation | MO1 | 0.761 | 0.936 | 0.936 | 0.946 | 0.636 | 2.040 |

| MO2 | 0.803 | 2.347 | |||||

| MO3 | 0.811 | 2.460 | |||||

| MO4 | 0.840 | 2.805 | |||||

| MO5 | 0.793 | 2.333 | |||||

| MO6 | 0.822 | 2.700 | |||||

| MO7 | 0.836 | 2.814 | |||||

| MO8 | 0.794 | 2.469 | |||||

| MO9 | 0.805 | 2.476 | |||||

| MO10 | 0.704 | 1.691 | |||||

| Organizational ambidexterity | AD1 | 0.803 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.910 | 0.626 | 2.117 |

| AD2 | 0.772 | 1.855 | |||||

| AD3 | 0.786 | 1.982 | |||||

| AL1 | 0.798 | 2.138 | |||||

| AL2 | 0.809 | 2.142 | |||||

| AL3 | 0.780 | 1.947 | |||||

| Core functionality | CF1 | 0.891 | 0.866 | 0.866 | 0.918 | 0.788 | 2.258 |

| CF2 | 0.884 | 2.204 | |||||

| CF3 | 0.888 | 2.260 | |||||

| Substantial cost reduction | SCR1 | 0.878 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.910 | 0.626 | 2.249 |

| SCR2 | 0.894 | 2.316 | |||||

| SCR3 | 0.852 | 1.786 | |||||

| Sustainable shared engagement | SSE1 | 0.893 | 0.907 | 0.909 | 0.935 | 0.781 | 2.869 |

| SSE2 | 0.856 | 2.313 | |||||

| SSE3 | 0.906 | 3.044 | |||||

| SSE4 | 0.880 | 2.610 |

| CF | EO | MO | OA | SCR | SSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 0.815 | |||||

| EO | 0.673 | 0.804 | ||||

| MO | 0.694 | 0.565 | 0.766 | |||

| OA | 0.699 | 0.636 | 0.579 | 0.81 | ||

| SCR | 0.618 | 0.523 | 0.689 | 0.525 | 0.863 | |

| SSE | 0.675 | 0.689 | 0.587 | 0.571 | 0.652 | 0.794 |

| Construct | R-Square | Q-Square | R-Square Adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frugal innovation capability | 0.818 | 0.660 | 0.817 |

| Organizational ambidexterity | 0.560 | 0.466 | 0.557 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Beta Coefficients (β) | T Statistics (t-Value) | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | EO → FIC | 0.219 | 3.598 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H1b | MO → FIC | 0.252 | 3.962 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H2a | EO → OA | 0.292 | 3.070 | 0.002 *** | Supported |

| H2b | MO → OA | 0.506 | 5.224 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| H3 | OA → FIC | 0.529 | 7.799 | 0.000 *** | Supported |

| Second Order Construct (Frugal innovation capability) | |||||

| CF → FIC | 0.833 | 24.922 | 0.000 *** | ||

| SCR → FIC | 0.861 | 36.918 | 0.000 *** | ||

| SSE → FIC | 0.890 | 24.675 | 0.000 *** | ||

| Hypothesis | Path | Beta Coefficients (β) | T Statistics (t-Value) | p-Values | Confidence Interval | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.025 | 0.975 | ||||||

| H4a | EO → OA → FIC | 0.155 | 2.944 | 0.003 | 0.052 | 0.258 | Supported |

| H4b | MO → OA → FIC | 0.268 | 4.204 | 0.000 | 0.151 | 0.403 | Supported |

| Variance Accounted for (VAF) of the Mediator Variable for OA | |||||||

| IVs | Mediator | DV | Indirect effect | Total effect | VAF (%) | Type of mediation | |

| EO | OA | FIC | 0.155 | 0.373 | 41.6 | Partial complementary | |

| MO | OA | FIC | 0.268 | 0.520 | 51.5 | Partial complementary | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sengura, J.D.; Mu, R.; Zhang, J. Towards Frugal Innovation Capability in Emerging Markets within the Digitalization Epoch: Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2000-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030098

Sengura JD, Mu R, Zhang J. Towards Frugal Innovation Capability in Emerging Markets within the Digitalization Epoch: Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(3):2000-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSengura, Josephat Deusidedith, Renyan Mu, and Jingshu Zhang. 2024. "Towards Frugal Innovation Capability in Emerging Markets within the Digitalization Epoch: Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 3: 2000-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030098

APA StyleSengura, J. D., Mu, R., & Zhang, J. (2024). Towards Frugal Innovation Capability in Emerging Markets within the Digitalization Epoch: Exploring the Role of Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(3), 2000-2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030098