Abstract

Consumers often rely on evaluations such as online reviews shared by other consumers when making purchasing decisions. Online reviews have emerged as a crucial marketing tool that offers a distinct advantage over traditional methods by fostering trust among consumers. Previous studies have identified group similarity between consumers and reviewers as a key variable with a potential impact on consumer responses and purchase intention. However, the results remain inconclusive. In this study, we identify self-construal and group similarity as key factors in the influence of online review ratings on consumers’ purchase intentions. We further investigate the role of consumers’ self-construal in shaping consumers’ perceptions of online reviews in terms of belongingness and diagnosticity. To test the hypothesis, we conducted a 2 (online review rating) × 2 (group similarity) × 2 (self-construal) ANOVA on 276 subjects collected through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and contrast analysis and PROCESS macro model 12 were used for the interaction effect analysis and moderated mediation analysis. Our findings reveal that consumers with an interdependent self-construal are sensitive to both review ratings and group similarity with regards to their purchase intentions. They demonstrate a positive purchase intention when both group similarity and online review ratings are high. However, their purchase intention is not influenced by review ratings when group similarity is low. Conversely, consumers with an independent self-construal exhibit a more positive purchase intention when the online review rating is high, irrespective of group similarity. Additionally, our study highlights the mediating roles of perceived diagnosticity and belongingness in the relationship between online review ratings, group similarity, self-construal, and purchase intentions. Results show significant indirect effects for perceived diagnosticity and belongingness, meaning that the impact of online review ratings on purchase intention is mediated by these two variables. The outcomes of our research offer theoretical and practical implications concerning online reviews and suggest new avenues for future research in the area of online consumer behavior.

1. Introduction

In today’s digital age, consumers no longer rely solely on traditional advertising for information on product purchases [1]. To make decisions, consumers actively seek information that incorporates evaluations and experiences from their fellow consumers, notably through online reviews. Studies indicate that more than half of consumers consider online reviews to be a critical source of information when deciding on a purchase [2]. This behavioral shift can be attributed to the fact that most consumers place greater trust in recommendations from their peers than in traditional advertising [3]. Consequently, online reviews have become critical communication channels for companies [4,5].

Previous studies have emphasized the importance of considering reviewer characteristics when determining the impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchasing decisions [6,7]. Among these characteristics, the perceived similarity between the review group and the consumer stands out as a crucial factor [8,9]. Generally, a higher perceived similarity leads to greater trust in and conformity to the reviews [9,10]. This is because perceived similarity to a specific group can significantly influence consumer perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors [11]. However, conflicting findings exist, with some studies suggesting that similarities to the online review group may not affect consumers’ purchase intentions [12] or may even have a negative impact [13]. These findings demonstrated that the impact of perceived similarity varies depending on consumers’ needs and interests. This suggests that to effectively examine the influence of perceived similarity in online reviews, consumer characteristics must be taken into account in the study. Self-construal is a variable that influences consumers’ perceptions of their relationships with others and the extent to which groups shape consumers’ attitudes and behaviors [14]. In other words, self-construal is a variable that must be considered when investigating the impact of group similarity in online reviews. However, previous studies have shown limited interest in this aspect. By presenting self-construal as a key variable, we aim to derive more meaningful results and implications.

Given the inconclusive results of previous research, the influence of group similarity in online reviews remains unknown. Therefore, for companies to successfully implement marketing strategies utilizing online reviews, it is crucial to examine when and under what circumstances group similarity between consumers and the online review group exerts an influence. In this study, the concept of self-construal is introduced to investigate this effect. Self-construal refers to how individuals perceive themselves in relation to others, which can significantly influence their reaction to online reviews [14]. Self-construal is a variable that affects consumers’ perceptions of relationships with others and the degree of group influence on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors [15,16]. In other words, self-construal is a variable that must be considered when examining the influence of group similarity in online reviews. However, unfortunately, there was a lack of interest in this in previous studies. We aim to derive clear results and implications by presenting self-construal as a key variable.

Previous studies have highlighted that marketing strategies employing social norms, such as online reviews, exert social influence that significantly affects consumer behavior [17]. Social influence is broadly categorized into informational influence (diagnosticity of information) and normative influence (belongingness to a group) [18,19]. These influences suggest that consumer conformity to majority evaluations stems from consumers being more likely to perceive information as accurate when part of a group norm. We predicted that the influence of online reviews would differ depending on consumers’ self-construal and group similarity. Specifically, consumers with an independent self-construal, perceiving themselves as “me”, tend to refer to the opinions of others to confirm confidence in themselves, regardless of who those others are [20]. They use the reviews of others to enhance the accuracy of their choices and boost their confidence. Therefore, irrespective of their similarity to the review group, the higher the online review rating, the higher the purchase intention of consumers with an independent self-construal. Conversely, consumers with an interdependent self-construal perceive themselves as “us”, and tend to strive for harmony within the in-group by accepting the in-group’s opinions [20]. Consequently, they are more influenced by online reviews from the in-group than the out-group, and online reviews are expected to have a normative influence rather than an informational influence on them. Consequently, consumers with an interdependent self-construal will exhibit more positive purchase intentions when their in-group’s online review ratings are higher.

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, we examined the impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions, with a focus on group similarity and self-construal. Previous studies emphasized that group similarity must be considered when examining the effectiveness of online reviews. However, previous studies failed to yield consistent results due to their inadequate consideration of consumers’ characteristics. This study proposes self-construal as a key moderating variable and examines how group similarity has differential influence depending on the type of consumer. Furthermore, informational and normative influences are presented as mediating factors between online reviews and the mechanism by which influences are activated. This is based on the interaction of group similarities and self-construal. The results of this study are expected to have practical implications for companies that use online reviews as marketing tools.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Influence of Online Reviews (Informative and Normative)

Online reviews are user-generated product-related information provided by consumers based on their experiences, and constitute the most common form of online word-of-mouth communication [21]. Previous research has indicated that online reviews are perceived as more authentic and persuasive than traditional advertisements and communication strategies [22,23]. Consequently, online reviews significantly influence other consumers’ purchasing decisions. Previous studies have suggested that positive online reviews create favorable consumer responses such as consumer trust, positive attitudes toward the product, and purchase intention [24,25,26,27].

Moreover, online reviews wield a strong social influence. The most crucial factor influencing consumer purchase behavior is the online review rating [1,28]. Companies present consumers’ evaluations in the form of star ratings to convey opinions about a product [29]. When the opinion of a majority of online reviewers about a product is showcased, consumers are encouraged to align themselves with that prevailing sentiment.

Previous studies have noted that online reviews using ratings, among other elements, are representative of marketing using social norms [29,30,31]. Social norms-related marketing significantly influences consumers in two ways [19]. The first is the informational influence. This social influence arises from consumers’ desire for accurate information to use in decision making. When purchasing a product, consumers seek cues to reduce uncertainty and ensure that products meet their expectations. When ratings indicate that many people have a specific evaluation or have taken certain actions, consumers perceive the information as useful and accurate for their own decision making, conformed to established norms. Positive evaluations for a specific product indicate a high likelihood that the product will meet consumer expectations [9,32]. In other words, the informational influence of online reviews serves as highly diagnostic information that assists consumer decision making.

The second type is the normative influence. This is the motivation that consumers feel to meet the expectations of others, arising from their desire to maximize social outcomes related to reward and punishment [33]. These consumers tend to conform to established norms to positively shape others’ perceptions of them and avoid negative consequences, such as disappointment or criticism. Consequently, consumers accept others’ opinions to receive compensation or avoid punishment, even if a decision is incorrect [34,35]. In other words, online reviews serve as group norms and consumers seek a sense of belonging to the group by following online reviews.

In summary, online reviews have both informational and normative effects. The informational influence of online reviews leads consumers to perceive information as more diagnostic, whereas the normative influence fosters a stronger sense of belonging. Consequently, the more positive the content of the online review, the higher the purchase intention of consumers for the product.

2.2. Group Similarity

Perceived social norms compel consumers to align with the expressed opinions in online reviews. Positive online reviews contribute to more favorable product evaluations and increased purchase intentions. However, the impact of online reviews is determined not only by the content but also by the characteristics of the reviewer [36], and certain groups can use their social influence to heighten consumers’ awareness [37].

Existing research highlights the pivotal role of perceived similarity between consumers and reference groups [32], suggesting that consumers engage in social comparison to assess themselves relative to others, especially with those sharing similar attributes [38]. Even in online shopping contexts, group similarity remains a critical factor to consider, as it exerts a significant influence on consumers’ purchasing decisions [10,39]. Previous studies have indicated that individuals are more likely to align with the behavior of groups that match factors such as age, gender, or personality [8,40,41]. For instance, Shang et al. [42] demonstrated that consumers were more likely to donate when informed about donations from people of the same gender. Similarly, Murray et al. [41] found a significant reduction in adolescent smoking when peers of the same age participated in an antismoking campaign. Goldstein et al. [9] emphasized the importance of group similarity in consumers’ social identity, revealing that consumers in a hotel aligned more with groups similar to themselves. Group similarity is a crucial variable for assessing consumer adherence to social norms.

However, other studies have indicated that group similarity does not consistently influence consumer attitudes or behaviors. Moon and Sung [13] demonstrated that consumers with a high need for uniqueness deliberately diverge from the opinions of groups with a high similarity to maintain their uniqueness. In their study, group similarity had a negative effect on consumer behavior. Moreover, Racherla et al. [12] found that the significance of group similarity on enhancing trust in online reviews occurs only in high-involvement situations. This is because, in consumer purchasing situations, similarity with the online review group serves as a central rather than a peripheral cue, diminishing the influence of similarity in low-involvement situations.

In summary, while similarity to online review groups can play a role in eliciting consumer responses, previous studies also suggest instances in which the influence of group similarity disappears or becomes negative. Therefore, for companies to utilize online reviews effectively, it is important to identify the factors that influence group similarity. To address this, self-construal, a variable representing consumers’ personal tendencies, is adopted as a key variable in this study. In particular, we examine how the social influence (informational/normative) of online reviews varies depending on the interaction between group similarity and self-construal.

2.3. Self-Construal

Self-construal refers to the extent to which individuals perceive themselves as distinct entities separated from others or as interconnected entities within relationships [14]. It encompasses both independent and interdependent self-construal [20]. Individuals with an independent self-construal think in terms of “I” and perceive themselves as unique entities, distinct from others. Conversely, those with an interdependent self-construal think in terms of “we” and perceive themselves as an integral part of the social context, and strive to maintain harmonious relationships with others [20,43,44]. Differences in thinking styles based on self-construal influence consumer perceptions of relationships as well as information processing, emotional expression, and perceptions of object fit [45,46,47].

Self-construal significantly influences how consumers process information presented by a reference group. Individuals with an independent self-construal value self-confidence over conforming to group norms during information processing [20]. This does not imply that they are impervious to group influence; rather, their aim is to enhance the accuracy of their judgments by seeking others’ opinions [32]. Online review ratings act as cues for those with an independent self-construal, boosting their confidence in the accuracy of their judgments. As a result, individuals with an independent self-construal tend to evaluate products more positively when they have higher review ratings, regardless of the type of review group. For them, a high rating indicates a low likelihood of product failure upon purchase.

By contrast, individuals with an interdependent self-construal place importance on relationships and group harmony, striving to reinforce bonds by adhering to in-group norms [43]. However, they do not value relationships with all groups equally [48]. Hesapci et al. [49] and Duclos and Barasch [50] noted that individuals with an interdependent self-construal are more influenced by the in-group than the out-group, indicating that those with an interdependent self-construal are more responsive to in-group than out-group influences, particularly when group similarity is high.

The anticipated variation in the social influence of online reviews, encompassing both informational and normative effects, is expected to vary based on group similarity and consumer self-construal. For individuals with an independent self-construal, the diagnostic perception due to informational influence is expected to be more prevalent. These consumers seek confidence in their purchases through reliable information [15,20,51]. They also use the opinions of others as a tool to evaluate their own judgments and decisions, regardless of the type of group [20]. Online reviews play a crucial role in this evaluative process [52]. High ratings in online reviews serve as valuable information, instilling confidence in potential buyers and guiding them toward satisfactory product choices [53]. Conversely, online reviews with lower ratings may serve an informative purpose, causing consumers to hesitate and reconsider their decision to purchase a particular product. Consequently, consumers with an independent self-construal are expected to experience higher diagnosticity when online reviews are positive, regardless of group similarity, with no significant change in the perception of belongingness based on group similarity or online reviews. This is because, for consumers with an independent self-construal, social influence operates primarily through informational influence rather than normative influence [51].

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The perceived diagnosticity of consumers with an independent self-construal increases when the online review rating is high (vs. low), irrespective of group similarity.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The perceived belongingness of consumers with an independent self-construal is not influenced by group similarity and the online review rating.

Individuals with an interdependent self-construal are expected to prioritize normative influence over informational influence in assessing online reviews [32]. Focused on conforming to group norms for relationship formation, they place greater value on relationships within their in-groups and are less influenced by out-groups [49,50]. Therefore, individuals with an interdependent self-construal are expected to perceive a greater sense of belongingness when online reviews from groups that are similar to their own are positive. However, when group similarity is low, perceived belongingness is not expected to be influenced by online ratings. Additionally, because they emphasize normative influence over informational influence in online reviews [51], no differences in the perceptions of diagnosticity are expected based on group similarity and online review ratings. Based on these considerations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The perceived diagnosticity of consumers with an interdependent self-construal is not influenced by group similarity and the online review rating.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The perceived belongingness of consumers with an interdependent self-construal changes according to group similarity and the online review rating.

Hypothesis 4a (H4a).

When group similarity is high, perceived belongingness increases more when the online review rating is high (vs. low).

Hypothesis 4b (H4b).

When group similarity is low, perceived belongingness does not change based on the online review rating.

Consumer purchase intentions are expected to vary according to group similarity, online review ratings, and self-construal. Consumers with an independent self-construal that emphasizes accuracy in decision making [15,20,51] perceive greater diagnosticity in online reviews that are positively rated by many people, which leads to a more positive purchase intention.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The purchase intention of consumers with an independent self-construal is more positive when the online review rating is high (vs. low), regardless of group similarity.

However, consumers with an interdependent self-construal, who make decisions based on in-group opinions [49,50,54], will perceive a different level of belongingness and thus have different purchase intentions based on group similarity and online review ratings. When group similarity is high, perceived belongingness increases, and purchase intention is more positive when the online review rating is high compared to when it is low. However, when group similarity is low, there will be no difference in purchase intention because they are not affected by the online review rating of the out-group. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses were derived:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The purchase intention of consumers with an interdependent self-construal changes according to group similarity and the online review rating.

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

When group similarity is high, purchase intention is more positive when the online review rating is high (vs. low).

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

When group similarity is low, purchase intention does not differ based on the online review rating.

Finally, we anticipate that the impact of online review ratings, group similarity, and self-construal on consumers’ purchase intentions will be mediated by perceived diagnosticity and belongingness. As previously mentioned, consumers with an independent self-construal, who base their decisions on informational rather than normative social cues [15,20,51], are expected to determine purchase intention based on perceived diagnosticity. Conversely, consumers with an interdependent self-construal, who base their decisions on normative influence [20,51], are expected to form purchase intentions based on perceived belongingness. Based on these premises, the following hypotheses were derived:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The influence of the online review rating, group similarity, and self-construal on purchase intention is mediated by perceived diagnosticity and perceived belongingness.

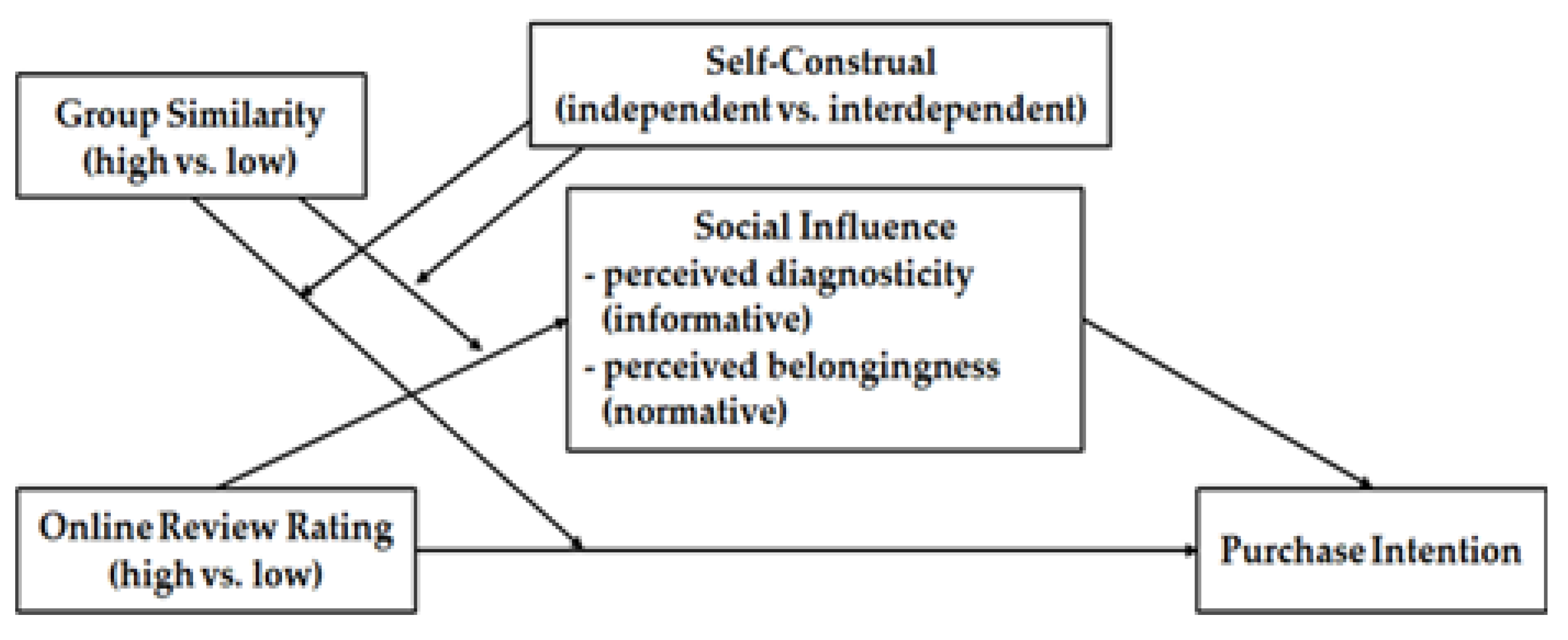

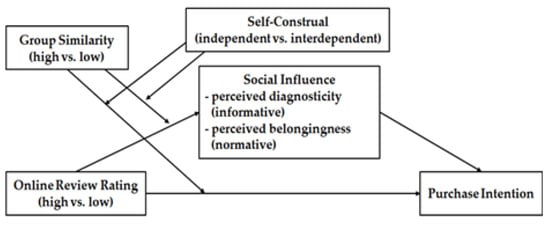

Figure 1 depicts the research framework of this study.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Framework and Data Collection

We investigated the impact of online review ratings, group similarity, and self-construal on consumer purchase intentions. Furthermore, perceived diagnosticity and belongingness were introduced as mechanisms underlying this influence.

The experiment was conducted from 17 July 2023 to 20 July 2023. A total of 267 subjects participated in the experiment in exchange for a small incentive (USD 0.6) through Amazon MTurk. All participants were residents of the United States, comprising 166 men (62.2%) with a mean age of 34.15 (SD = 9.96, range = 21–74) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

3.2. Experimental Design and Procedure

This study employed a 2 (online review rating: high vs. low) × 2 (group similarity: high vs. low) × 2 (self-construal: independent vs. interdependent) between-subjects factorial design. Participants were randomly assigned to experimental conditions based on online review ratings, group similarity, and self-construal, resulting in eight groups, each group comprising 27–49 subjects.

First, participants engaged in tasks related to self-construal. Tasks pertaining to self-construal involved priming and manipulation checks to assess self-construal. The participants’ self-construal was primed using the method outlined by Chen [46] and Gardner et al. [55]. To prime self-construal, participants were presented with a task involving paragraphs corresponding to different self-construal types (i.e., independent or interdependent). Participants in the independent self-construal condition were instructed to read short paragraphs about a city trip and then count the number of pronouns in the text. The pronouns presented to them were singular words (e.g., he, she, me, I, you, mine, and yours). Participants in the interdependent self-construal condition were given the same task, but the pronouns presented to them were plural words (e.g., we, they, our, and their). Following this task, participants responded to 6 questions assessing the effectiveness of the self-construal manipulation (e.g., independent: focused on “myself” vs. interdependent: “me and my family”).

Next, to manipulate group similarity, participants were asked about their mobile phone brand (e.g., Samsung Galaxy, Apple iPhone). They were then presented with experimental stimuli containing product information and online reviews (see Appendix A). The stimuli provided information about earbuds released by a fictitious American venture company designed to be compatible with mobile phones, including Samsung Galaxy and Apple iPhones. To highlight group similarities, participants were informed that the reviews were written by users of Samsung Galaxy and Apple iPhones. High group similarity was established when both the participants and the reviewers used the same mobile phone brand, whereas low group similarity occurred when they used different brands (e.g., high group similarity: participant’s brand—Samsung, reviewers’ brand—Samsung). Product ratings in the experimental stimuli were based on user review ratings and categorized into the following two conditions: high and low ratings. The review ratings were presented to the participants in the form of star ratings.

After viewing the stimulus, participants responded to 3 items to check the manipulation of group similarity, 4 items assessing perceived diagnosticity (informative influence), 5 items evaluating feelings of belongingness (normative influence), and 4 items measuring their intention to purchase. Finally, participants answered demographic questions. The measurement items and reliability of the constructs are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement items and reliabilities.

4. Results

4.1. Manipulation Checks

We conducted a manipulation check for the variables of interest (self-construal and group similarity). In the 2 (group similarity) × 2 (review rating) × 2 (self-construal) analysis of variance (ANOVA) focusing on the self-thought index, self-construal exhibited a significant main effect (F = 21.570, p < 0.001). Participants with an independent self-construal (M = 5.46) were more self-focused than those with an interdependent self-construal (M = 4.73). For the other-thoughts index, in the 2 (similarity) × 2 (review rating) × 2 (self-construal) ANOVA, the main effect of self-construal was also significant (F = 10.275, p < 0.05), with individuals with an interdependent self-construal (M = 5.34) showing more focus on others than those with an independent self-construal (M = 4.82).

In the analysis of perceived similarity, through the 2 (group similarity) × 2 (review rating) × 2 (self-construal) ANOVA, the main effect of group similarity was significant (F = 16.171, p < 0.001). Participants perceived greater group similarity when the mobile phone brands they used matched with the reviewers’ (M = 5.43) compared to when they did not (M = 4.88). In the manipulation checks for self-construal and group similarity, the effects of the other variables were not significant (all p > 0.1).

4.2. Independent Self-Construal: Perceived Diagnosticity (Informative)/Belongingness (Normative)

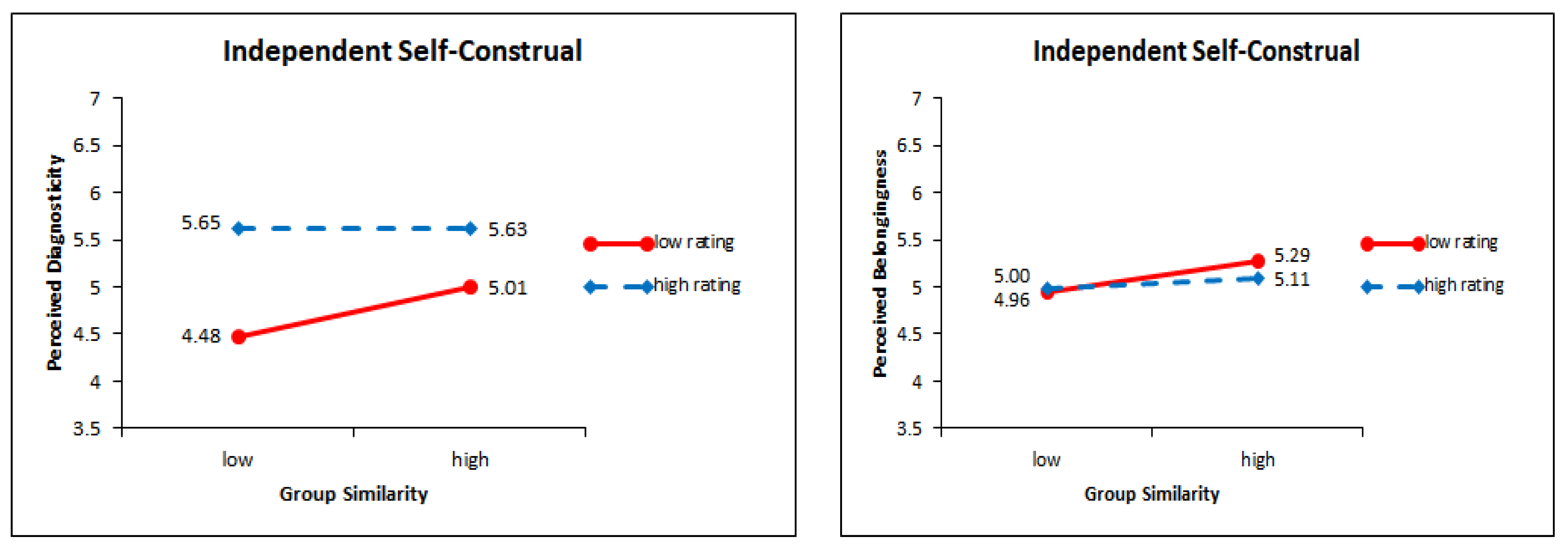

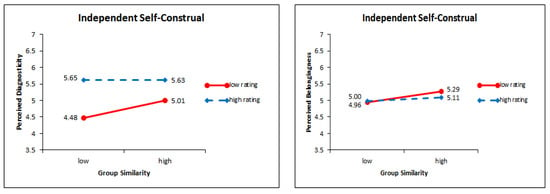

An ANOVA was conducted to examine the influence of self-construal, group similarity, and review ratings on perceived diagnosticity and belongingness (Table 3 and Table 4). The following results were obtained: First, the analysis on perceived diagnosticity showed a marginally significant main effect of group similarity (F = 3.284, p = 0.071), indicating that participants perceived higher diagnosticity when group similarity was high (M = 5.34) compared to when it was low (M = 5.16). Second, the main effect of the review ratings was significant (F = 10.989, p < 0.05), with participants perceiving higher diagnosticity for high-rated reviews (M = 5.47) than for low-rated reviews (M = 5.06). Third, the three-way interaction among self-construal, group similarity, and review ratings on perceived diagnosticity was significant (F = 6.987, p < 0.05). In contrast, the analysis of participants with an independent self-construal (Figure 2 showed that these individuals perceived online reviews with higher ratings as more diagnostic than low-rated ones, irrespective of group similarity. Specifically, in the case of high group similarity, participants perceived greater diagnosticity when the online review rating was high (M = 5.63) compared to when it was low (M = 5.10; F = 4.714, p < 0.05). Similarly, under low group similarity, they perceived greater diagnosticity for high-rated reviews (M = 5.65) compared to when it was low (M = 4.84; F = 12.119, p < 0.05), supporting H1. This means that, as proposed in Hypothesis 1, consumers with independent self-construal perceived greater diagnosticity of online reviews with high (vs. low) ratings when group similarity was high (vs. low). Furthermore, analyses based on online review ratings showed no significant difference in diagnostic perceptions concerning group similarity in either the high or low online review rating groups (high review rating—low group similarity: 5.65 vs. high group similarity: 5.63; F = 0.010, p > 0.1) (low review rating—low group similarity: 4.84 vs. high group similarity: 5.10; F = 1.115, p > 0.1).

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results: perceived diagnosticity.

Table 4.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results: perceived belongingness.

Figure 2.

Independent self-construal: three-way interaction effects on perceived diagnosticity (informative)/belongingness (normative).

An ANOVA on perceived belongingness showed that none of the main effects were significant (all p > 0.1). More importantly, the three-way interaction effect on perceived belongingness was significant (F = 5.765, p < 0.05). In contrast, focusing on participants with an independent self-construal (Figure 2) revealed that these individuals did not perceive belongingness differently depending on group similarity and online review ratings (high group similarity—low review rating: 5.29 vs. high review rating: 5.11; F = 0.325, p > 0.1) (low group similarity—low review rating: 4.96 vs. high review rating: 5.00; F = 0.021, p > 0.1). These results support H2. In other words, as proposed in Hypotheses 1 and 2, the results confirmed that consumers with an independent self-construal perceive diagnosticity over belongingness when evaluating online review ratings. Furthermore, in both groups with high and low online review ratings, no significant difference was observed in the perception of the sense of belongingness based on group similarity (high review rating with low group similarity: M = 5.11; F = 0.133, p > 0.1: low review rating with low group similarity: M = 4.96 vs. high group similarity: M = 5.29; F = 1.096, p > 0.1).

4.3. Interdependent Self-Construal: Perceived Diagnosticity (Informative) and Belongingness (Normative)

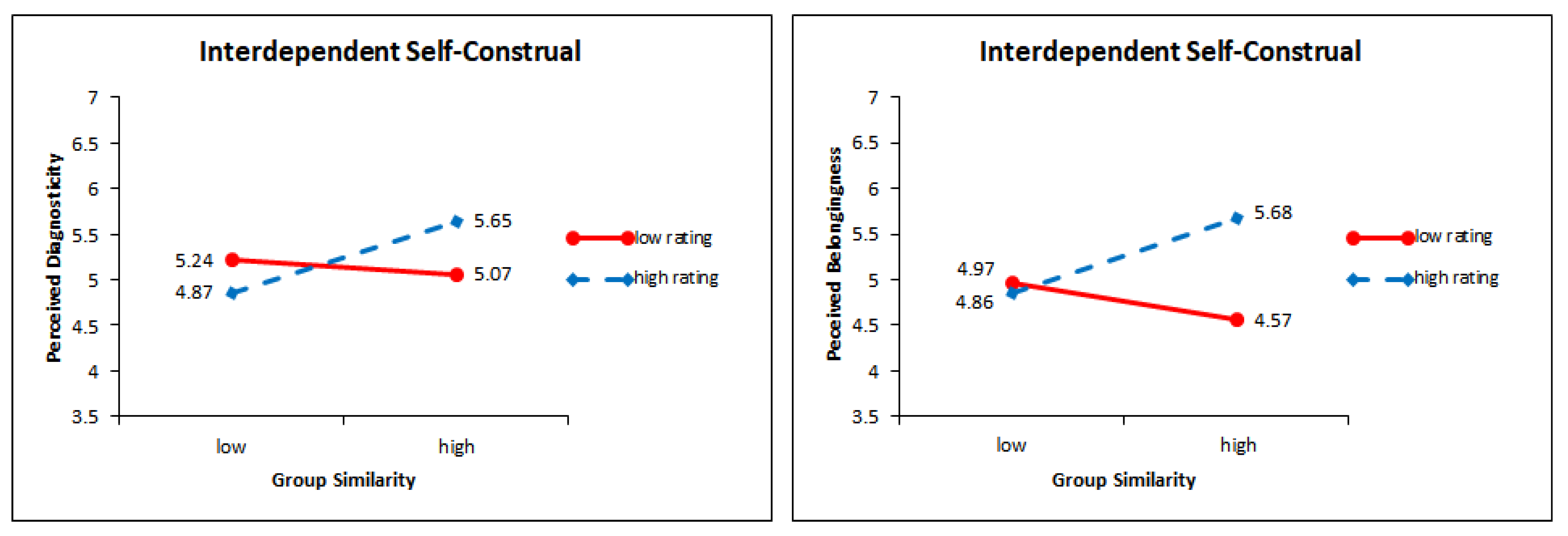

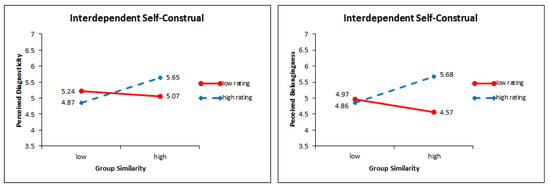

The contrast analysis of the perceived diagnosticity of participants with an interdependent self-construal (Figure 3) showed that their perceptions of diagnosticity varied depending on the review rating and group similarity. In the case of high group similarity, participants perceived greater diagnosticity when the review rating was high (M = 5.65) compared to when it was low (M = 5.07; F = 7.604, p < 0.05). However, in the case of low group similarity, perceived diagnosticity did not vary depending on the review rating (low review rating: 5.24 vs. high: 4.87; F = 2.320, p > 0.1). Contrary to the prediction of Hypothesis 3, consumers with interdependent self-construal perceived online reviews with high ratings as more useful compared to those with low ratings when group similarity was high. This result indicates that H3 was not supported. Furthermore, where online review ratings were high, individuals perceived greater diagnosticity when group similarity was high than those with low group similarity (high online review rating—low group similarity: 4.87 vs. high group similarity: M = 5.65; F = 10.785, p < 0.05). However, in instances where the review ratings were low, there was no significant difference in the perception of diagnosticity based on group similarity (low review rating with low group similarity: M = 5.24 vs. high group similarity: M = 5.07; F = 0.617, p > 0.1). In other words, individuals with an interdependent self-construal perceived greater diagnosticity from reviews when both group similarity and review ratings were high.

Figure 3.

Interdependent self-construal: three-way interaction effects on perceived diagnosticity (informative)/belongingness (normative).

The results of the contrast analysis of the perceived belongingness of participants with an interdependent self-construal showed significant differences in perceived belongingness based on group similarity and online review ratings (Figure 4). Specifically, in conditions of high group similarity, participants reported a greater sense of belongingness when the review rating was high (M = 5.68) compared to when it was low (M = 4.57; F = 16.872, p < 0.001). Consumers with interdependent self-construal perceived a higher sense of belongingness through high (vs. low) online review ratings when group similarity was high. However, in scenarios with low group similarity, perceived belongingness did not significantly differ based on the online review rating (low review rating: M = 4.97 vs. high: 4.86; F = 0.123, p > 0.1). This implies that for consumers with interdependent self-construal, when group similarity was low, the impact of online review ratings on the perception of belongingness was not significant. These results show H4a and H4b were supported. Further analysis on perceived belongingness based on online review ratings revealed that, in cases where the review ratings were high, individuals experienced heightened perceived belongingness when group similarity was high compared to when it was low (high review rating with low group similarity: M = 4.86 vs. high group similarity: 5.68; F = 7.120, p < 0.05). By contrast, when the review rating was low, there was no significant difference in the perception of belongingness based on group similarity (low review rating with low group similarity: M = 4.97 vs. high group similarity: M = 4.57; F = 2.074, p > 0.1).

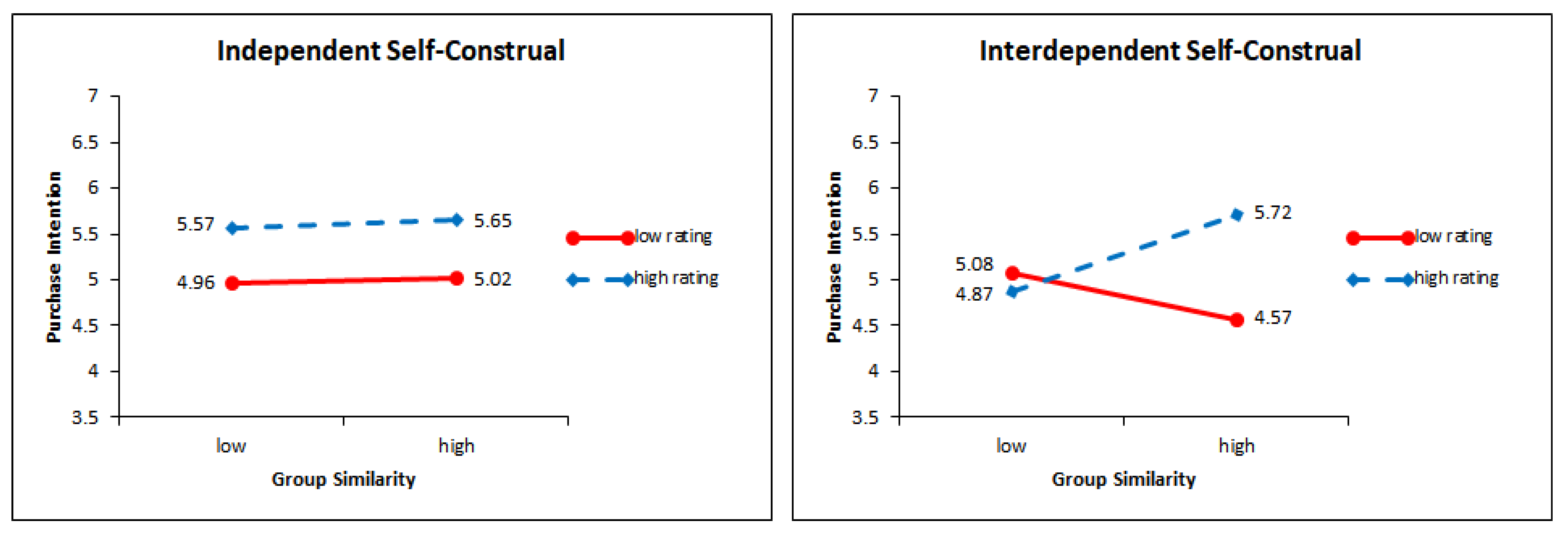

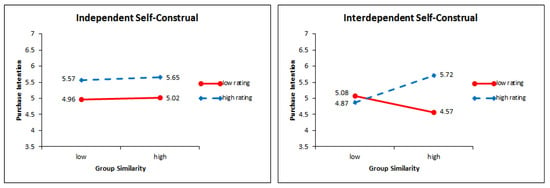

Figure 4.

Self-construal (independent and interdependent): three-way interaction effects on purchase intention.

4.4. Purchase Intention

The results of the ANOVA (Table 5) revealed that the main effect of the online review rating was significant (F = 15.939, p < 0.001), indicating that participants had a more positive purchase intention when the review rating was high (M = 5.47) compared to when it was low (M = 4.86). The main effect of self-construal was marginally significant (F = 3.058, p = 0.082). Compared with participants with an interdependent self-construal (M = 5.02), those with an independent self-construal showed a higher purchase intention (M = 5.32). Moreover, the three-way interaction among self-construal, group similarity, and the review rating on the purchase intention was significant (F = 6.008, p < 0.05). The contrast analysis results (Figure 4) indicated that participants with an independent self-construal had a more positive purchase intention with high review ratings, regardless of group similarity. In high group similarity conditions, participants exhibited a positive purchase intention when the online review rating was high (M = 5.65) compared to when it was low (M = 5.02; F = 4.937, p < 0.05). Similarly, in situations with low group similarity, purchase intention was more positive when the online review rating was high (M = 5.57) compared to when it was low (M = 4.96; F = 4.971, p < 0.05).

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results: purchase intention.

The purchase intention of the participants with an interdependent self-construal varied based on group similarity and the review rating. In situations with high group similarity, their purchase intention was more positive when the online review rating was higher (M = 5.72) compared to when it was low (M = 4.57; F = 21.996, p < 0.001). However, in situations with low group similarity, purchase intention did not differ according to the review rating (review rating—low: 5.08 vs. high: 4.87; F = 0.553, p > 0.1) (Figure 4). Thus, H5 and H6 (H6a and H6b) were supported.

In summary, consumers with an independent self-construal who perceive diagnosticity in high review ratings exhibit more positive purchase intentions when review ratings are high (vs. low), irrespective of group similarity. However, consumers with an interdependent self-construal, who perceive both diagnosticity and belongingness in high review ratings only when group similarity is high, show more positive purchase intentions in high (vs. low) review ratings of groups with high similarity.

Analysis based on online review ratings revealed individuals with an independent self-construal did not exhibit different purchase intentions based on group similarity, regardless of whether the review rating was high or low (high online review rating with low group similarity: M = 5.57 vs. high group similarity: 5.65; F = 0.095, p > 0.1; low review rating with low group similarity: M = 4.96 vs. high group similarity: 5.02; F = 0.040, p > 0.1). In contrast, individuals with an interdependent self-construal displayed varied purchase intentions according to group similarity under both high and low review ratings conditions (high review rating with low group similarity: M: 4.87 vs. high group similarity: 5.72; F = 9.381, p < 0.05) (low review rating-low group similarity: 5.08 vs. high group similarity: 4.57; F = 4.046, p < 0.05).

4.5. Mediation Analysis (Perceived Diagnosticity/Belongingness)

Mediation analysis was conducted to explore how perceived diagnosticity and perceived belongingness mediate the effects of online review ratings, group similarity, and self-construal on purchase intention. Model 12 of the PROCESS macro was applied for analysis [63], with bootstrapping analysis involving 10,000 resamples to assess the mediation effects [64]. In this model, online review ratings were considered the independent variable, group similarity and self-construal were the moderating variables, perceived diagnosticity and belongingness served as mediating variables, and purchase intention was the dependent variable. The results indicated that the influence of online review ratings on purchase intention was mediated by perceived diagnosticity and belongingness, indicating significant indirect effects for perceived diagnosticity (indirect effect = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.2106–1.4136) and perceived belongingness (indirect effect = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.0832–0.9519). Therefore, H7 was supported.

Next, the following analysis was conducted to examine the path of influence of each variable (online review rating, group similarity, self-construal) on consumers’ purchase intentions. Upon examining the specific paths of influence of online review ratings based on self-construal and group similarity, the mediating effect of perceived diagnosticity (Table 6) was not significant in the condition of interdependent self-construal and low group similarity. For subjects with an independent self-construal, perceived diagnosticity mediated the influence of online review ratings on purchase intention, regardless of group similarity. Conversely, in subjects with an interdependent self-construal, the mediating effect of perceived diagnosticity was significant only when group similarity was high. Finally, the mediating effect of perceived belongingness was not significant for participants with an independent self-construal and was significant only in the condition of high group similarity for participants with an interdependent self-construal (Table 7).

Table 6.

Results of mediation analysis for perceived diagnosticity.

Table 7.

Results of mediation analysis for perceived belongingness.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of online review ratings, group similarity, and self-construal on consumer purchase intentions. Additionally, we explored the underlying mechanisms of perceived belongingness and diagnosticity in shaping these intentions. The results highlighted varied patterns in purchase intentions based on the interplay between group similarity and online review ratings for consumers with interdependent and independent self-construals. Specifically, consumers with an interdependent self-construal were more influenced by group similarity, showing heightened purchase intentions when online review ratings were high. However, in situations with low group similarity, purchase intentions remained unaffected by online review ratings. Conversely, consumers with an independent self-construal were significantly influenced by online ratings, showing more positive purchase intentions when the ratings were high, irrespective of group similarity.

Previous studies examining the impact of group similarity in online reviews have yielded inconsistent results. However, this study demonstrated that the conflicting findings from previous research could be reconciled by considering self-construal. Additionally, we investigated the underlying mechanisms of perceived belongingness and diagnosticity in shaping these intentions. Prior research suggests that marketing strategies employing social norms exert social influence, perceived by consumers as either informational or normative [9,18,19,32]. Our findings indicate that the influence of social norms on consumer responses varies depending on their self-construal. Among consumers with an interdependent self-construal, perceived belongingness and diagnosticity played a mediating role. Conversely, for those with an independent self-construal, purchase intentions were solely mediated by perceived diagnosticity. In essence, this study is significant, as it confirms that differential perception (information usefulness and belongingness) operates based on self-construal regarding the influence of online review ratings and group similarity on consumer response (Table 8).

Table 8.

Results of hypothesis.

5.2. Academic Implications

These findings have several important implications. First, the study corroborated the role of group similarity in enhancing the effectiveness of online reviews, building on existing literature that highlighted the influence of social norms and social influence [9,17]. Notably, this study manipulated group similarity within the context of consumer–brand dynamics, offering meaningful insights that are distinct from previous studies [65,66]. Second, the research revealed noteworthy variances in consumers’ purchase intentions contingent on group similarity and self-construal within the framework of online reviews. This study contributes to the literature on self-construal and social norms by confirming that the types of groups influencing consumers with independent or interdependent self-construals are distinct.

Finally, this study proposes that social influence, comprising normative and informational components, serves as the underlying mechanism for the positive impact of online reviews on purchase intention. Importantly, it reveals that the prominence of each influence type shifts based on group similarity and self-construal. For consumers with an independent self-construal, perceived diagnosticity (informational influence) mediates the impact of online reviews on purchase intentions. Conversely, for those with an interdependent self-construal, both perceived belongingness (normative influence) and perceived diagnosticity (informational influence) mediate this effect. Understanding the different mechanisms at play distinguishes this study from previous research [9,11], emphasizing the contextual dependence of reviews contingent on group similarity and individual consumer characteristics.

5.3. Practical Implications

The study also offers practical insights for marketers aiming to use online reviews to formulate effective strategies. First, it highlights the significant role of group similarity in influencing purchase intentions, demonstrating that consumers perceive a high level of group similarity solely by being informed that they are using the same product brand as the reviewer. Consequently, companies can enhance perceived group similarity by leveraging consumers’ past purchase history rather than relying on demographic information or community affiliation details.

Second, the results underscore that the effects of online reviews and group similarity can vary based on consumers’ self-construal. Therefore, companies should implement diverse online review strategies based on consumers’ self-construal. For those with an independent self-construal, positive online reviews are effective regardless of group similarity because they assess the quality and utility of products through reviews. By contrast, because consumers with an interdependent self-construal are influenced primarily by product evaluations from their in-group, marketers should use positive reviews from the same consumer group.

Third, understanding consumers’ self-construal is crucial for companies seeking to implement effective online review strategies. Collecting data on targeted consumers and inferring their self-construal based on demographics, age, gender, and culture can inform tailored strategies. Finally, companies can manipulate consumer self-construal through priming techniques within purchasing situations. Priming, as demonstrated in this study’s experiment, enables temporary changes in consumers’ tendencies. Consumers’ self-construal can be manipulated by having them engage in specific tasks, as demonstrated in this study, but it can also be manipulated by the messages they encounter. Additionally, consumers’ self-construal may vary depending on their motivations for purchasing a product [56]. For instance, when consumers aim to buy a product for personal satisfaction or enjoyment, their self-construal may shift toward independence. On the other hand, when purchasing a product for the well-being or safety of their family, it may become more interdependent. By incorporating priming methods, message types, and purchase situations that influence self-construal, companies can establish more effective online review strategies.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

We would like to address several limitations and propose directions for future research based on our findings. First, despite observing variations in consumers’ purchase intentions based on the variables examined in this study, we noted that purchase intention was relatively high across all groups. This may be attributable to the nature of the experimental product, the Bluetooth earbuds, which are readily accessible to consumers. Bluetooth earbuds, which are available in diverse brands and price ranges, may engender inherently positive consumer attitudes. Future research should consider conducting experiments using different products to ensure the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the comparatively elevated purchase intention may be attributed to the online review ratings presented to the participants. In this study, the stimuli were accompanied by review ratings of 4.6 points in the high condition and 3 points in the low condition. While a significant difference was noted between these two levels, it may be challenging to categorize a rating of 3 points as low. Consequently, future research should adjust the ratings to align with the conditions and the characteristics of the target group.

Second, the products utilized in prior studies on online reviews (e.g., printers, sneakers, electronic devices, and shampoos) were confined to a few categories [57,58]. In line with this trend, our study used electronic devices as experimental stimuli. However, online shopping platforms offer a wide array of products beyond electronic devices. For instance, consumers may purchase experience products such as tickets for movies or musical performances online. Future research should explore a broader range of product categories to enhance the external validity of our findings. Specifically, when dealing with experience products, where consumer perceptions are influenced by higher uncertainty, reliance on other people’s reviews may play a more significant role. Therefore, future studies should consider these aspects.

Third, consumers’ online purchase intentions may be influenced by factors such as the characteristics of the reviewer or review. For instance, giving cues that enhance review reliability, such as top reviewers or best reviews [59], may increase consumer perceptions of information accuracy. Even in situations where group similarity is high, review or reviewer ranks can exert a more significant influence. Future research should explore these aspects to better understand the dynamics of online shopping.

Finally, it is noteworthy that, even for products with high review ratings, the presence and number of visual images in the review can vary. Kim et al. [60] highlighted that consumers respond positively to reviews accompanied by images or those with a substantial number of images. Future research in this domain has the potential to offer valuable insights for companies seeking to optimize their online product presentations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A. and J.L.; methodology, Y.A. and J.L.; analysis, Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.; writing—review and editing, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the datasets analyzed during the study are available from the first author or the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Experimental Stimuli

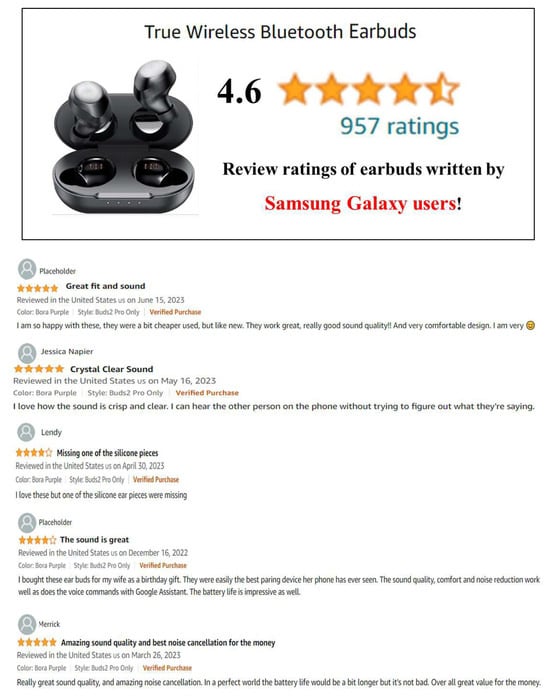

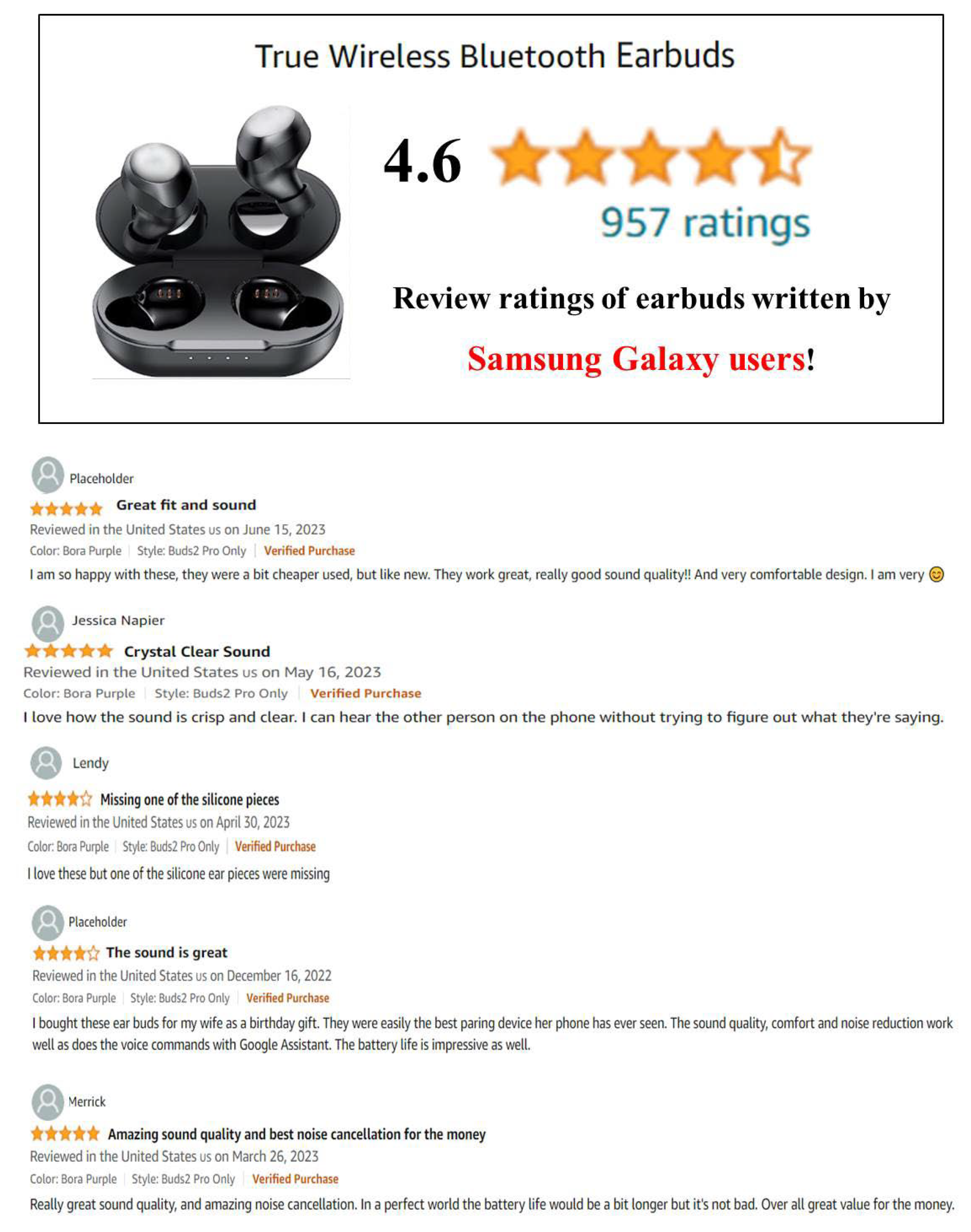

Appendix A1. High Rating (Samsung Galaxy) Condition

This review is about earbuds, a new product launched by an American venture company. These earbuds are compatible with all phone brands, such as the Samsung Galaxy and Apple iPhone, regardless of the model. The company conducted consumer testing before launching the product, and posted reviews of each mobile phone brand used by consumers. Samsung Galaxy user reviews were as follows:

Figure A1.

Samsung Galaxy users’ reviews.

Figure A1.

Samsung Galaxy users’ reviews.

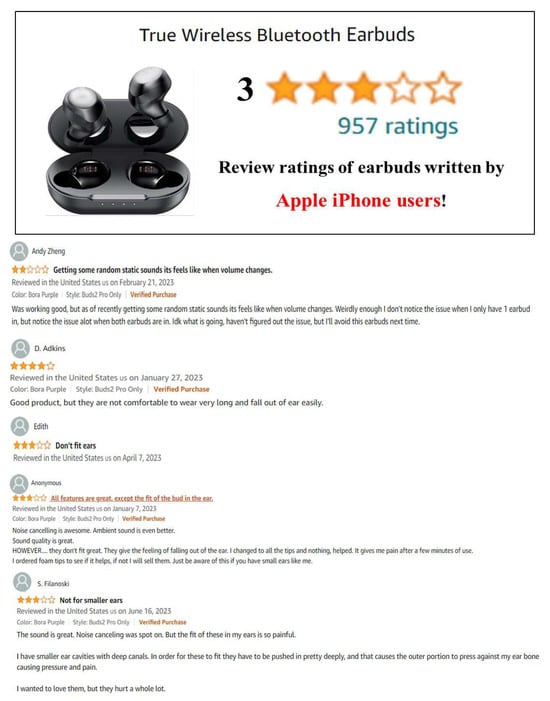

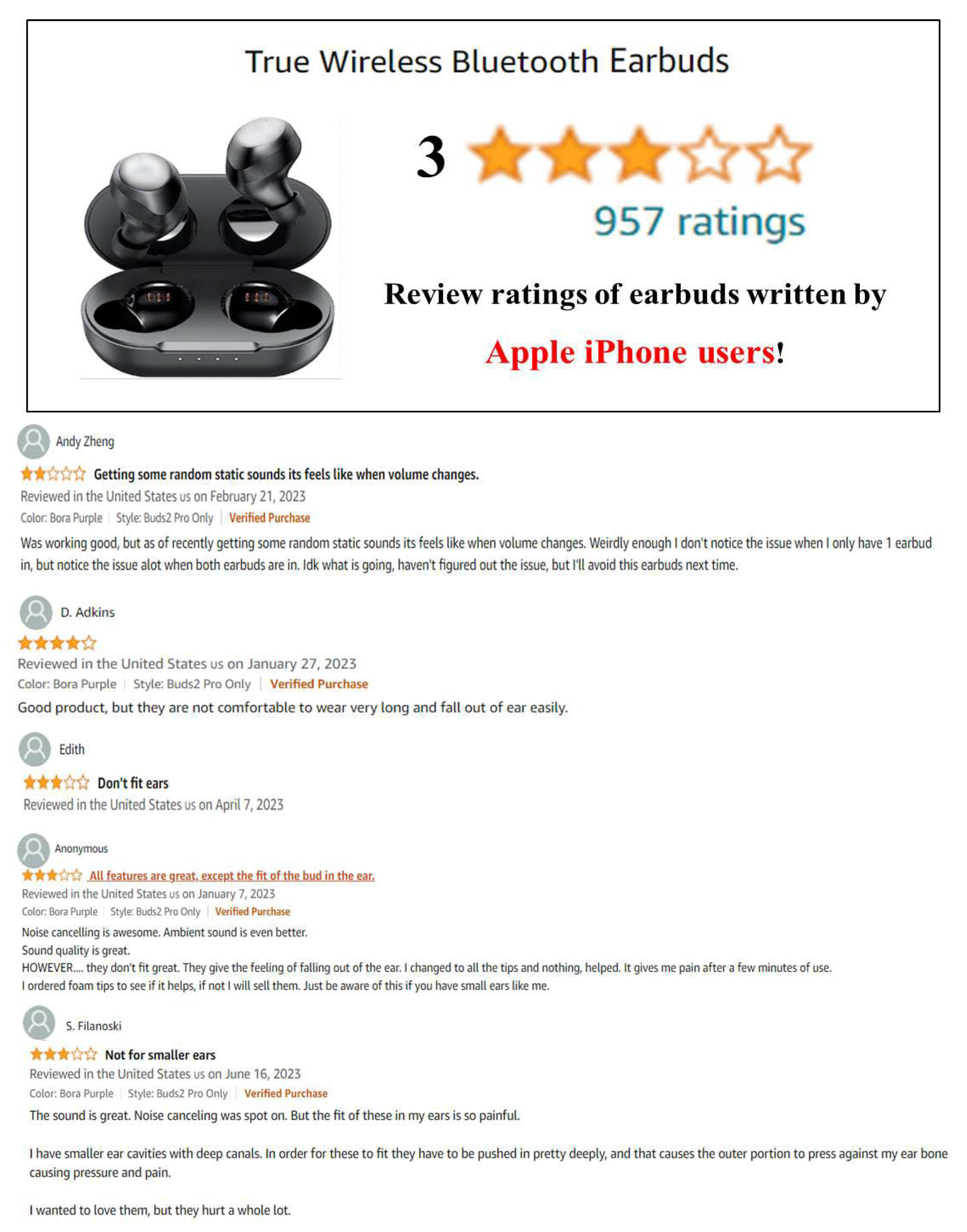

Appendix A2. Low Rating (Apple iPhone) Condition

This review is about earbuds, a new product launched by an American venture company. These earbuds are compatible with all phone brands, such as Apple iPhone and Samsung Galaxy, regardless of the model. The company conducted consumer testing before launching the product, and posted reviews for each mobile phone brand used by consumers. Apple iPhone users’ reviews are as follows.

Figure A2.

Apple iPhone users’ reviews.

Figure A2.

Apple iPhone users’ reviews.

References

- Maslowska, E.; Malthouse, E.C.; Bernritter, S.F. Too good to be true: The role of online reviews’ features in probability to buy. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintel. Seven in 10 Americans Seek Out Opinions before Making Purchases. 3 June 2015. Available online: https://www.mintel.com/press-centre/seven-in-10-americans-seek-out-opinions-before-making-purchases/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Nielsen. Consumer Trust in Online, Social and Mobile Advertising Grows. April 2012. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/insights/2012/consumer-trust-in-online-social-and-mobile-advertising-grows/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Bernritter, S.F.; Verlegh, P.W.; Smit, E.G. Why nonprofits are easier to endorse on social media: The roles of warmth and brand symbolism. J. Interact. Mark. 2016, 33, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, D.H.; Han, I. The different effects of online consumer reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions depending on trust in online shopping malls: An advertising perspective. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M. Examining the effect of reviewer expertise and personality on reviewer satisfaction: An empirical study of TripAdvisor. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Duan, S.; Shang, S.; Pan, Y. What makes a helpful online review? Empirical evidence on the effects of review and reviewer characteristics. Online Inf. Rev. 2021, 45, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstude, K.; Mussweiler, T. What you feel is how you compare: How comparisons influence the social induction of affect. Emotion 2009, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, J.; Gopinath, S.; Verhaal, J.C.; Yazdani, E. The influence of the online community, professional critics, and location similarity on review ratings for niche and mainstream brands. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 1065–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagenczyk, T.J.; Purvis, R.L.; Shoss, M.K.; Scott, K.L.; Cruz, K.S. Social influence and leader perceptions: Multiplex social network ties and similarity in leader–member exchange. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racherla, P.; Mandviwalla, M.; Connolly, D.J. Factors affecting consumers’ trust in online product reviews. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Sung, Y. Individuality within the group: Testing the optimal distinctiveness principle through brand consumption. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Maheswaran, D. The effects of self-construal and commitment on persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Shavitt, S. The “me” I claim to be: Cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Wang, J.J.; Silvera, D.H. How does cultural self-construal influence regulatory mode? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhukya, R.; Paul, J. Social influence research in consumer behavior: What we learned and what we need to learn?–A hybrid systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnkrant, R.E.; Cousineau, A. Informational and normative social influence in buyer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Trost, M.R. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology; Gilbert, D.T., Fiske, S.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 151–192. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation: Culture and the self. Psycological Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N.; Kolomiiets, A. The impact of text valence, star rating and rated usefulness in online reviews. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, S.; Pavlou, P.A. Evidence of the effect of trust building technology in electronic markets: Price premiums and buyer behavior. MIS Q. 2002, 26, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, L.M.; Neijens, P.C.; Bronner, F.; De Ridder, J.A. “Highly recommended!” The content characteristics and perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2011, 17, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, A.G.; Minazzi, R. Web reviews influence on expectations and purchasing intentions of hotel potential customers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnawirawan, N.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Balance and sequence in online reviews: How perceived usefulness affects attitudes and intentions. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnawirawan, N.; Eisend, M.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. A meta-analytic investigation of the role of valence in online reviews. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 31, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Browning, V. The impact of online reviews on hotel booking intentions and perception of trust. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Yeu, M.; LEE, D.-H. Effects of online reviews’ volume, distribution and consumers’ self-construal on movie purchase decision. Korean J. Advert. 2013, 24, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Srinivasan, R. Social influence effects in online product ratings. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, W.W.; Trusov, M. The value of social dynamics in online product ratings forums. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Feinberg, F.; Wedel, M. Leveraging missing ratings to improve online recommendation systems. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Lee, J. The effects of the social norms marketing on the consumers’ purchase intention in the online shopping context: Focusing on the social support level, group similarity, self-construal. J. Channel Retail. 2015, 20, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRidder, R.; Schruijer, S.G.; Tripathi, R.C. Norm violation as a precipitating factor of negative intergroup relations. In Norm Violation and Intergroup Relations; DeRidder, R., Rama, C., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992; pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.D.; Fairey, P.J. Informational and normative routes to conformity: The effect of faction size as a function of norm extremity and attention to the stimulus. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W. Attitude change: Persuasion and social influence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 539–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, P.N.; Rothgerber, H.; Wood, W.; Matz, D.C. Social norms and identity relevance: A motivational approach to normative behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 1295–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behavior: Buying Having and Being; Pearson: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Online reviews: The impact of power and incidental similarity. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, L.L.; Ganley, R.; Pierce-Otay, A. Similarity and satisfaction in roommate relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.M.; Johnson, C.A.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittelmark, M.B. The prevention of cigarette smoking in children: A comparison of four strategies 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 14, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Reed, A.; Croson, R. Identity congruency effects on donations. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N. Shifting selves and decision making: The effects of self-construal priming on consumer risk-taking. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, J.; Lu, F.-C. “I” value justice, but “we” value relationships: Self-construal effects on post-transgression consumer forgiveness. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, R. How far can a brand stretch? Understanding the role of self-construal. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y. Who I am and how I think: The impact of self-construal on the roles of internal and external reference prices in price evaluations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Chang, H.H. “I” follow my heart and “we” rely on reasons: The impact of self-construal on reliance on feelings versus reasons in decision making. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1392–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesapci, O.; Merdin, E.; Gorgulu, S. Your ethnic model speaks to the culturally connected: Differential effects of model ethnicity in advertisements and the role of cultural self-construal. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, R.; Barasch, A. Prosocial behavior in intergroup relations: How donor self-construal and recipient group-membership shape generosity. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Mourali, M. Effect of peer influence on unauthorized music downloading and sharing: The moderating role of self-construal. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, S.; Wilk, V.; Lambert, C. A big data exploration of the informational and normative influences on the helpfulness of online restaurant reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filieri, R. What makes online reviews helpful? A diagnosticity-adoption framework to explain informational and normative influences in e-WOM. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Lee, J. The effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) fit and CSR consistency on company evaluation: The role of CSR support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Gabriel, S.; Lee, A.Y. “I” value freedom, but “we” value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Lee, A.Y. “I” seek pleasures and “we” avoid pains: The role of self-regulatory goals in information processing and persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Ha, S.; Im, H. The impact of perceived similarity to other customers on shopping mall satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Shao, B.; Zhang, Y. Effect of product presentation videos on consumers’ purchase intention: The role of perceived diagnosticity, mental imagery, and product rating. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 812579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhm, J.-P.; Kim, S.; Do, C.; Lee, H.-W. How augmented reality (AR) experience affects purchase intention in sport E-commerce: Roles of perceived diagnosticity, psychological distance, and perceived risks. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kwon, O.; Lee, I.; Kim, J. Companionship with smart home devices: The impact of social connectedness and interaction types on perceived social support and companionship in smart homes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.M.; Robbins, S.B. Measuring belongingness: The social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J. Couns. Psychol. 1995, 42, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.J. Corporate-, product-, and user-image dimensions and purchase intentions. J. Comput. 2011, 6, 1875–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch Jr, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.C.C.; Lam, L.W.; Chow, C.W.; Fong, L.H.N.; Law, R. The effect of online reviews on hotel booking intention: The role of reader-reviewer similarity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kong, D.; Huang, H. Homogenous or heterogeneous? Demand effect of reviewer similarity in online video website. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 37, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).