Abstract

This systematic review synthesized and analyzed clinical findings related to the effectiveness of innovative technological feedback for tackling functional gait recovery. An electronic search of PUBMED, PEDro, WOS, CINAHL, and DIALNET was conducted from January 2011 to December 2016. The main inclusion criteria were: patients with modified or abnormal gait; application of technology-based feedback to deal with functional recovery of gait; any comparison between different kinds of feedback applied by means of technology, or any comparison between technological and non-technological feedback; and randomized controlled trials. Twenty papers were included. The populations were neurological patients (75%), orthopedic and healthy subjects. All participants were adults, bar one. Four studies used exoskeletons, 6 load platforms and 5 pressure sensors. The breakdown of the type of feedback used was as follows: 60% visual, 40% acoustic and 15% haptic. 55% used terminal feedback versus 65% simultaneous feedback. Prescriptive feedback was used in 60% of cases, while 50% used descriptive feedback. 62.5% and 58.33% of the trials showed a significant effect in improving step length and speed, respectively. Efficacy in improving other gait parameters such as balance or range of movement is observed in more than 75% of the studies with significant outcomes. Conclusion: Treatments based on feedback using innovative technology in patients with abnormal gait are mostly effective in improving gait parameters and therefore useful for the functional recovery of patients. The most frequently highlighted types of feedback were immediate visual feedback followed by terminal and immediate acoustic feedback.

1. Introduction

The basic motor functions of the human being, such as gait, can be altered because of a wide range of traumatalogical, neurological, rheumatic, etc. pathologies [1,2]. Hip arthrosis [3], knee osteoarthritis [4], strokes, hemiparesis [5,6,7], or lower-limb amputations [8], all produce important alterations to gait patterns.

Developments in technology and information technology (IT) have enabled the development of new techniques for gait re-training based on feedback supplied by electronic devices. This has been demonstrated by authors such as Druzbicki et al. [5], Basta et al. [9], Zanoto et al. [10] and Segal et al. [11].

The basic principle of feedback is the ability to voluntarily control and change certain bodily functions or biological processes when information is provided about them [12]. The main advantage of feedback is the supply of information about a specific biological process about which the patient does not consciously have information [13].

Currently, technology is developing towards facilitating the functional recovery of the patient, sometimes even without the physiotherapist. These treatments incorporate: robot assisted movement [10,14,15,16], virtual reality technology [17] and inertial monitoring devices [18,19] amongst others. Some of these systems use visual [5,11,20], acoustic [15,21] and/or haptic [22,23] feedback in a coherent and detailed way, adapted to each user’s individual needs [24]. New technologies based on feedback are extremely useful in the area of rehabilitation for re-educating an altered function or teaching a new one [2,25]. These aspects represent the main objectives of physiotherapy [13,25].

However, technological systems are frequently adopted in clinical practice without their efficacy having been proven. Researchers need to focus on providing clinical findings [24]. Therefore, the effects of these novel devices need to be measured [26,27] on different study populations, considering gait parameters, therapeutic guidelines adopted, clinical results obtained, systems of assessment used, etc. Similarly, we need to analyze the efficacy of different types of extrinsic feedback, in other words, that coming from an external source [28]. In this case, electronic devices will provide concurrent or immediate feedback, that is, feedback received simultaneously with the action (for example, during the foot support phase, the patient knows the amount of vertical reaction force of the floor on the limb or during walking the patient knows his/her speed); terminal or retarded feedback, or feedback received when the action is finished (for example, at the end of a tour the patient knows information about his/her progress, length of the steps, speed, kinematic of the knee, etc.); acoustic (e.g., beep, oral, etc.), visual (e.g., video cameras, displays, etc.) or haptic information (usually vibrations in some body area such as the soles of the feet) [29]; etc. Finally, this study also considers whether extrinsic feedback offers knowledge of performance (KP), in other words, characteristics of performance (e.g., if the foot bears the right direction, if the trunk remains erect during the action, etc.); or knowledge of result (KR) [30] (correct or incorrect action, score, etc.); whether this is descriptive (description of errors) or also prescriptive (how to correct errors) [24] (for example, we describe an error in walking saying that the patient is dragging the foot during the swing phase of the step. However, to correct it, we ask the patient to flex the hip and knee more when taking the step, so that the foot does not touch the ground).

Hence, the need to review, synthesize and analyze clinical findings related to the use of different kinds of technology-based feedback and their effectiveness in improving certain parameters in functional gait recovery.

2. Materials and Methods

The method was based on the PRISMA protocol [31].

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

An electronic search of PUBMED, PEDro, WOS, CINAHL, and DIALNET was carried out from January 2011 to December 2016. In addition to this, we checked the reference lists of the included studies. Mesh terms (Medical Subject Headings) for English language or Decs Terms (Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud) for Spanish database and search strategies are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Mesh and Decs Terms put into groups by mean.

Table 2.

Search strategy.

2.2. Study Selection and Inclusion Criteria

The papers included in this review had to meet the following criteria:

- -

- Population: Mainly patients with a modified or abnormal gait (i.e., spatiotemporal gait parameters) due to a pathology such as cerebral palsy, hip orthoprosthesis, lower member amputation, knee ligamentoplasty, etc.

- -

- Interventions: application of technology-based feedback (haptic and/or visual and/or acoustic) to assist functional gait recovery as much as possible. The feedback had to be received by the patient directly (external feedback).

- -

- Comparisons: Any comparison between different kinds of feedback (visual, haptic, immediate/concurrent, retarded/terminal, etc.) applied using technology. Or any comparison between technological and non-technological feedback, usual care or an alternative exercise therapy/intervention not based on feedback.

- -

- Outcomes: Any validated measures of parameters or aspects associated to gait, such as: pain, functionality, balance, unload weight bearing, spatiotemporal parameters (speed, cadence, step length), kinematic data (range of movement-ROM) and score by specific gait assessment test or scale (i.e., Up and Go, chair-stand time).

- -

- Study design: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

- -

- Measure of methodological quality of RCT: A minimum of 4 points according to PEDro Scale. That is, “fair” and “high” quality studies [32] (see Quality Appraisal).

- -

- Language: Studies reported in English or Spanish.

- -

- Setting: Not limited to a particular setting.

The titles and abstracts of the search results were screened to check if a study met the pre-established inclusion criteria. We obtained the full text article of those studies which met the criteria, and documented the causes for any exclusions at this stage.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer (A.J.M.) and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (G.C.M.), using a table designed to detail information on study features, participant characteristics, feedback modality, technology employed (for feedback and assessment), interventions, comparisons, and outcome measurements.

2.4. Quality Appraisal

Apposite studies were assessed for methodological quality using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) critical appraisal tool [33]. This method was valid and reliable for assessing the internal validity of a study (criteria 2–9). We also evaluated the adequacy of the statistical information for interpreting the results (criteria 10–11) [34,35,36]. PEDro consists of 11 criteria overall; although criterion 1 refers to the external validity of the trial and is not included in the final score [34]. Each criterion could be Yes (one point) or No (0 points), with a maximum score out of ten. Only “fair” (scores 4/5) and “high” (scores ≥ 6/10) quality studies [32] were included in this review.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

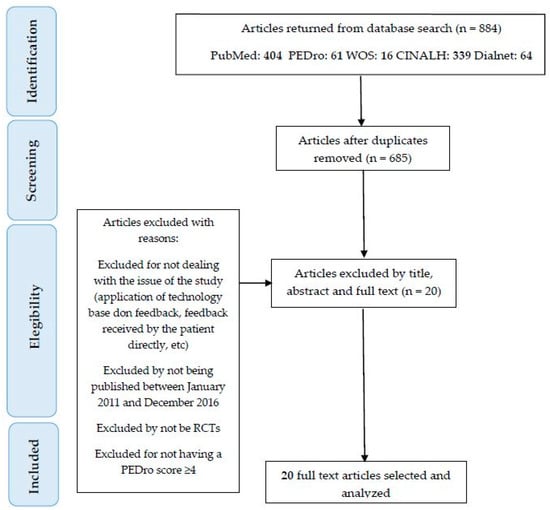

We found 884 articles in the electronic databases. Most of them in Pubmed (404), and the rest in PEDro (61), WOS (16), Cinahl (339) and Dialnet (64). Following the removal of duplicates, 776 articles were screened by title, abstract and full-text, due to: not including feedback technology, not applying the feedback directly to the patient, not being RCT, not using feedback for gait functional recovery, not having ≥4 score in PEDro Scale. After the screening, 20 studies were left for inclusion in this review.

Figure 1 shows the search and study selection process, which was based on PRISMA [37] guidelines.

Figure 1.

Research method of this study.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

A detailed summary of the features and results of each selected study is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies.

3.3. Quality Assessment

The results of the PEDro scoring are shown in Table 4. All the selected papers rated “fair” and “high” quality (≥4 points).

Table 4.

Completed PEDro quality appraisal.

The item “Subjects were randomly allocated to groups” (2) was scored by all papers because it was an inclusion criterion. Besides, the items “Eligibility criteria were specified” (1) and “The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome” (10) were scored in all studies apart from 2.

Although the studies were considered to be of “fair” and “high” quality, there were two items with 0 scores: “Blinding of all subjects” (5) and “Blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy” (6).

3.4. Participant Characteristics

Relative to the population in this review, neurological patients were found in 15 out of 20 papers (75%). That is: 8 of stroke [5,7,16,19,21,39,41,42]; 1 of cerebral palsy [17]; 2 of hemiparesis [14,18]; 4 of Parkinson’s [19,23,38,40]; and 1 with incomplete spinal cord injury [15]. Byl et al. [19] include stroke and Parkinson’s in the same research. Besides, 2 studies were found with patients in the orthopaedic area [11,20]; and 3 more with healthy subjects [10,22,26].

All participants were adults bar one [17].

3.5. Feedback Technology

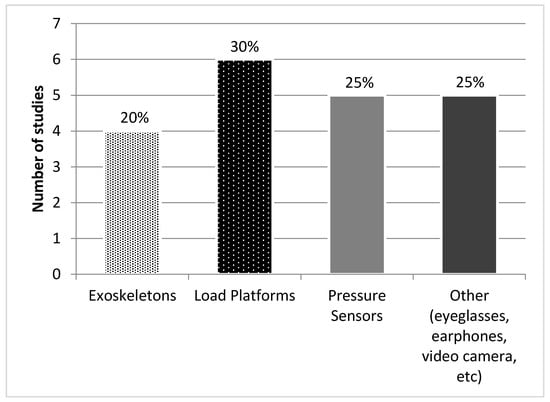

Four studies [10,14,15,16] stood out due to their use of exoskeletons, although only 2 of them produced feedback, Alex II [10] and Lokomat [16]. The others used complementary technology which only assists gait: Gar [14] and Lokomat [15] in this case without feedback.

Six studies were based on load platforms [5,14,18,22,40,42], such as Smart Equitest® [40], Gait Trainer® [5,18] and Functional Trainer System® [42]; and 5 on pressure sensors [11,19,22,26,39] for example Emed-Q100® [39] or Ped-Alert TM120® [21].

The feedback technology was supplemented with other tools in 8 papers: treadmills [5,11,14,16,23,40], exoskeletons [14,15], forearm crutches [15], and metronome [18]. Figure 2 summarizes the use of technologies.

Figure 2.

Feedback technologies.

3.6. Feedback Modalities

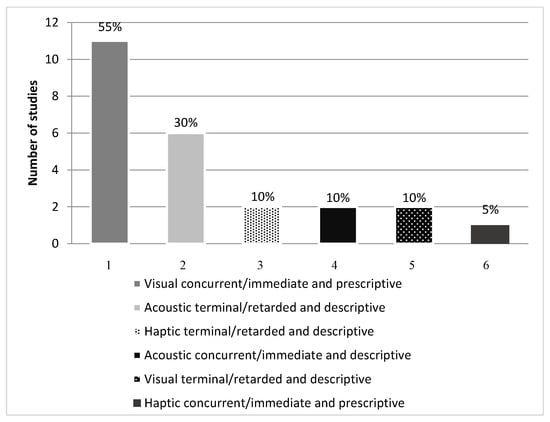

The studies used different types of feedback: visual, acoustic and haptic; terminal/retarded and concurrent/immediate; descriptive and prescriptive; with both KR and KP. Visual feedback was used in 60% of the papers, acoustic in 40% and haptic in 15%. Terminal/retarded feedback was used in 55% and concurrent/immediate in 65%. Descriptive feedback was used in 50% of cases, with prescriptive in 60%. KP was featured in 45% and KR in 70% (Table 5).

Table 5.

Outline of the types of feedback used in each study.

The combination of types of feedback used in descending order was: 55% visual, concurrent/immediate and prescriptive feedback [5,10,11,14,16,17,18,19,20,40,42]; 30% acoustic, terminal/retarded and descriptive [5,7,15,17,21,41]; 10% haptic, terminal/retarded and descriptive [22,26], acoustic, concurrent/immediate and descriptive [10,38] and visual, terminal/retarded and descriptive feedback [39,40]; 5% combined haptic, concurrent/immediate and prescriptive feedback [23] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Types of feedback.

3.7. Assessment Technology

The technology used to assess gait in the selected studies was as follows: 3D movement analysis systems [5,18,20,23]; platform or treadmill force sensors [10,11,22,26,40]; pressure sensors in insoles [19], platforms [26] and parallel bars [7,15,21,22,40,41], pulsometer and ergospirometry [16]; functional training system [42]; exoskeleton [15]; and Gaitway [11].

3.8. Interventions and Comparators

In six studies the application of the feedback systems lasted 20 min [5,11,14,15,18,40], although some took up to 90 min [19]. Results also included some complementary treatments to technological feedback, such as balance [5], strength training [19], postural correction [23], stretching [7,40], speech therapy [16] and medications [11].

3.9. Outcome Measures and Results

The measurements taken in the studies were in descending order of frequency: speed, 75% [5,7,14,15,17,18,19,22,23,38,40,41]; step length, 50% [17,18,19,23,38,40,42]; Up and Go Test, 20% [19,21,22,41]; cadence, 20% [5,15,18,23]; ROM, 10% [18,23]; 10MWT 10% [5,42]; Berg Scale 10% [19,41] and 2MWT 10% [5,38]. Other parameters approached to a lesser degree were: IQR [5], peak respiratory rate [16], peak heart rate [16], etc.

For the most frequently considered parameters (speed, step length, Up and Go Test, Cadence, ROM, 10MWT and Berg Scale) the studies with significant outcomes were: 58.33% for speed [7,15,17,19,23,40,41]; 62.5% for step length [17,19,23,40,42]; 75% for TUG [21,22,41], 50% for cadence [15,23], 100% for ROM [18,23], 50% for 10MWT [42] and 100% for Berg Scale [19,41]. The clinical interventions of these studies with significant outcomes, except one [18], were effective in improving the parameters indicated. Table 6 summarizes these studies.

Table 6.

Interventions with technology-based feedback and their effectiveness in improving gait parameters.

4. Discussion

The aim of this review was to synthesize clinical findings regarding the effectiveness of technological feedback in assisting functional gait recovery. Studies defending such effectiveness versus non-technological feedback include: Baram et al. [17], Ki et al. [21], El-Tamawy et al. [23] and Sungkarat et al. [41] amongst others. The authors of this study defend the use of technological feedback but not at the cost of usual care such as: mirror therapy [7], assisted gait [7] or verbal feedback [19], etc. In other words, technological feedback and traditional physiotherapy complement each other in assisting the functional recovery of the patient. To a lesser degree, other authors such as Brasileiro et al. [18], Byl et al. [19] or Hunt et al. [20], state that technological feedback did not obtain positive, or at least significant, results, in relation to other treatments.

In Physiotherapy, the current trend is to improve treatments using new technologies adapted as much as possible to the user needs. Furthermore, it is not only the system that must be individualized, but also the type of feedback used. To exemplify this trend, consider the GCH Control System [27], an instrumented forearm crutch that controls the loads exerted on the crutch when the patient has to partially discharge his/her affected limb. It includes a feedback mechanism to send information about these loads to both the physiotherapist and the patient. When the patient has deficiencies in their coordination skills, the first sessions are usually started with indirect feedback. That is, the therapist receives feedback from the system and verbalizes it to the patient. The patient finds it easier to understand the information through the physiotherapist, who verbally adapts it to their individual conditions (e.g., “Load a little more”, “Try to keep that same load”, “Be careful that you load more with the right stick than with the left”, etc.). The system also has the possibility of adapting the type of feedback (immediate, delayed, visual, auditory, etc.) according to the user's needs. For instance, based on our experience, the use of immediate feedback is easier for the patient and leads to a faster but less lasting result, so it is used when the patient has fewer skills. The delayed feedback is, on the contrary, more complex for the patient and the results come later, although they are more durable [43]. On the other hand, in the case of the GCH System the visual feedback is much simpler than the auditory feedback, which can only be used when the user completely dominates the former.

The articles analyzed in this review highlight how the feedback used when the subject is healthy is more complex [10,22] than when he/she is sick [7,15,17]. Also, in the present review, it is observed how there are parameters such as the cadence that can be easily corrected by means of a sound signal such as that emitted by a digital metronome or a more complex one by means of an exoskeleton [15,21,41]. On the other hand, deviations from the center of gravity are better worked by means of images [11,25].

However, it is worth mentioning that, again according to our experience, current technological systems have the tendency to personalize their treatments but without even nuancing the exact needs of the patient. It will be the therapist who makes the decision to use the technology in one way or another, always based on an initial and continuous assessment of the process and taking into consideration the coordinating, proprioceptive abilities of the user. The feedback received by the therapist for decision-making will be not only through technological means, but also through observational analysis. Both assessments, the technological and the visual or manual, are again complementary in the process of functional recovery of gait.

The technological devices, based on feedback, used by the different authors range from the complex to the basic. The complex group would include, for example: Biodex [5,18], Gaitway [11], GAR [14] or LOKOMAT [15]. The specific characteristics of each device means they each have pros and contras in terms of functionality. For example, LOKOMAT requires much more preparation time than GAR [14]. The basic devices include: heel switches [23], virtual glasses (used as computer monitor) and headphones [17], or a cane with a step-counting sensor [7]. The latter has been rendered obsolete as it has been superseded by other canes [27,44] with much more advanced technology and functions. These devices even have their own software designed specifically for functional gait recovery [27].

On the other hand, the high cost of these devices means that their everyday use is unfeasible despite their effectiveness [20]. Many authors [10,20,26], including those writing this article, favour efficiency versus the effectiveness of clinical technology in relation to financial, spatiotemporal and human resources [45]. In other words, clinical professionals require assessment and treatment systems which are feasible for everyday clinical practice, allowing adequate development of a process of functional [1,22] gait recovery. For instance, Quinzaños et al. [15] highlight the efficacy of the acoustic stimulus for re-training gait cadence and symmetry. As a result, a basic metronome [18] can be highly useful for functional gait recovery.

As this paper’s introduction shows, there are many different classifications of feedback. For example, depending on the sense used, it will be acoustic, visual or haptic [28]. Relating to the moment of the stimulus, there is immediate/concurrent or retarded/terminal feedback. Finally, if the information provides data about performance or result we would be talking about KP or KR [30]. The results of this review show that authors do not just use one isolated type of feedback, instead they sometimes prefer to combine them. The one used most on its own is visual feedback [5,10,11,14,16,17,18,19,20,39,40,42], which is also concurrent [5,10,11,14,16,17,18,19,20,23,38,40,42]. In contrast, combined, we find four articles with visual and acoustic feedback at the same time [5,10,17,38]: prescriptive and again concurrent visual feedback; and descriptive, concurrent or terminal, acoustic feedback. Summing up, of the RCTs selected in this review, 55% of the articles featured prescriptive and concurrent visual feedback [5,10,11,14,16,17,18,19,20,40,42], and 30% descriptive and terminal acoustic feedback [5,7,10,15,17,21,41]. Although many of the devices used in the clinical trials had more types of feedback available (for example, haptic [23,26]), the authors opted for concurrent feedback, either terminal acoustic or concurrent visual which are the most effective according to Agresta et al. [6]. Thus, it has been demonstrated that concurrent feedback produces the best short-term results [24], while retarded feedback obtains the best results in the long-term [46,47]. However, other authors such as Parker et al. [24] or Salmoni et al. [48] stress that feedback can be counterproductive for learning a complex task if the procedure is applied in too detailed a manner. In other words, detailed feedback can make it more difficult for the participant to understand or process other sensory information.

We must clarify that this statement refers especially to short-term learning, particularly if complex information is offered to patients with limited coordination skills. If we consider a long-term learning the patient has more time to assume complex information although the authors of this study advocate the progression in difficulty based on a continuous assessment of the process. Another handicap of complex and prolonged feedback is the creation of the patient's dependence on receiving feedback. In this sense, the patient responds to feedback automatically in a specific task but does not integrate the learning so it is unable to extrapolate it to other similar tasks [49].

On the other hand, all the information received by the patient can be descriptive (it simply states and describes the error) or prescriptive (it provides data on how to correct the error) [24]. When the correction is simple like in the aforementioned case of the instrumented forearm crutch, just by describing the load exerted the patient knows that he/she must exert more or less force. In other cases, the description and prescription of the correction are not so obvious. When a patient touches the ground with the foot in the swing phase of a step, the correction depends on the cause and this is multifactorial (kinematics, poor coordination, etc.). The patient may not flex the hip, knee or ankle sufficiently, either due to joint limitation or muscle weakness of the tibialis anterior in the case of dorsiflexion of the ankle, hamstrings for knee flexion or iliopsoas and anterior rectus of the quadriceps in the case of the hip. Another cause would be the lack of proprioception of the patient that prevents her/him from making the gesture or even carrying it out simultaneously (step and triple flexion of the lower limb at a time). In this case, the prescription must be offered by the physiotherapist based on the causes, in a progressive and individualized manner. Selective muscle strengthening exercises, manual therapy to gain range of motion in some joint or working the patient’s balance independently to the walking session may be prescribed.

Another example is arm movement during gait. Error detection and description can be easily implemented using technology. On the contrary, the prescription for its correction is usually more complex because again the causes are multiple: lack of integration of the arms in the body scheme, lack of dissociation between the scapular and pelvic waists, lack of mobility of the glenohumeral joint, etc. Deepening further, the patient can brace but not fluidly, i.e., without rotation of the shoulder girdle and without transferring the energy from proximal (trunk) to distal (arms), which would be incorrect. Even the patient may not swing arms in an opposing direction with respect to the lower limb, which would lead to an erroneous walking. Again the prescription must be made by the physiotherapist based on the cause and of course on a rigorous initial and continuous assessment.

Other authors such as Sigrist [49] affirm that to provide the idea of a movement, the feedback should be in principle prescriptive. Eventually, when the subject has internalized the action, descriptive feedback may be applied to make the correction more effective. Similarly, Sulzenbruck [50] states that, before the skill is acquired, prescriptive feedback is more effective than descriptive feedback. Still, there are authors such as Ki et al. [21] who use descriptive feedback (a beep to indicate that the weight load has been exceeded in the paretic limb) while others such as Segal et al. [11] opt for prescriptive feedback in his RCT (a graphic representation of the subject by means of a skeleton, on a screen, informs him how the optimal knee movement should be made).

Overall, the selected articles obtained significantly positive results in relation to the use of technological feedback. Even so, it should be noted that some specific parameters were not particularly significant. That is the case of stride speed or time [5,14,17,18,22,40], which can be influenced by complex robotized systems or exoskeletons, treadmills, supports etc., and the focus of the user’s attention on other parameters of interest. These show an improvement in overall gait despite not actually increasing speed.

As for the populations covered, most of the technological feedback applications were applied in the neurological field. The results of this review show that 75% came from that area [5,7,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,23,38,39,40,41,42]. Hence, feedback is capable of changing motor strategies in patients with neurological lesions [18], with the application of this type of treatment being more appropriate during early stages of rehabilitation [24]. As for other clinical areas, this review has only included 2 articles (10%) based on muscular-skeletal lesions [11,20]. They outlined the limitation of traditional physiotherapy in the recovery of lower-limb functions [51]. Only 3 articles (15%) used a sample of healthy subjects [10,22,26]. Despite being an RCT, it is sometimes necessary to perform research with healthy subjects to ascertain the efficacy of a new technological system before using it with patients requiring treatment. Continuing with the study population, it should be noted that 95% of the reviewed articles included samples of adult subjects [5,7,10,11,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,26,38,39,40,41,42]. Only 5% of the subjects were under 18 [17]. For this reason, we believe more scientific findings need to be generated in other clinical areas and in young population samples.

The following gait parameters were assessed in the selected RCTs, in descending order of frequency: speed (cm/s) [7,15,17,18,19,22,23,38,40,41], step length (m) [15,17,18,19,22,23,38,41,42], and cadence (steps/min) [5,15,18,23]. These parameters were chosen because the unit of gait is the step and time-space parameters are essential for its assessment [2,52,53,54,55]. The measurement devices were in some cases also those providing the feedback [7,10,14,19,26,39,40,41,42]. The majority measured short-term effects [5,7,14,15,16,18,19,20,21,23,41,42]. The few which measured long-term effects did not obtain conclusive results [11,39,40], which underlines the need for prospective studies.

As a final reflection, the authors of this study recognize that technological progress has led to the development of highly useful tools in the field of physiotherapy which complement conventional therapy. In no case are these technologies considered substitute media, in contrast to the opinion of Parker et al. [24]. Despite the multiple benefits which new technologies offer, a physiotherapist’s face-to-face treatment of a patient cannot be equaled by technological means. The personalized and intuitive adaptation of the health-care professional is the key to successful treatment.

5. Conclusions

Treatment based on feedback using innovative technology in patients with abnormal gait is mostly effective in improving gait parameters and therefore of use in the functional recovery of a patient.

Concurrent/immediate visual is the most frequently used type of feedback, followed by terminal/retarded acoustic. Also, prescriptive feedback and knowledge of result are the most frequent alternatives.

Most of the systems used are based on force and pressure sensors, normally accompanied by complementary software.

Walking speed is the most frequently evaluated parameter, with the majority of studies reporting significant improvements (in one study the changes were only significant after 3 months). The positive effect on the stride length is also found significant in most cases. In general, the number of studies with significant outcomes for the other parameters (such as balance or range of movement) is too low.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was supported by the Telefonica Chair “Intelligence in Networks” of the Universidad de Sevilla, Spain.

Author Contributions

Gema Chamorro-Moriana and José Luis Sevillano conceptualised the idea. Antonio José Moreno and Gema Chamorro-Moriana carried out the study selection, data extraction and manuscript drafting. Gema Chamorro-Moriana, Antonio José Moreno and José Luis Sevillano have been involved in critically revising for important intellectual contents. All authors contributed to the final version and approved the final paper for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 10MWT | 10-m Walk Test |

| ABC | Activities-Specific Balance Confidence |

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| AFO | Ankle Foot Orthosis |

| CG | Control Group |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ES | Effect Size |

| FAC | Functional Ambulation Classification |

| FC-RATE | Feedback Controlled Robotics Assisted Treadmill Exercise |

| FIM™ | Functional Independence Measure |

| FTS® | Functional Training System |

| FTSTS test | Five Times Sit To Stand |

| GAGT | GAR-Assisted Gait Training Group |

| GAR | Gait-Assistance Robot |

| GCB | “Bathroom Scale” Training Group |

| GCV | “Verbal Instruction” Training Group |

| GFB | “Haptic Biofeedback” Training Group |

| HRpeak | Peak Heart Rate |

| IG | Intervention Group |

| IQR | Barthel Index |

| IT | Information Technology |

| KOOS | Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score |

| KP | Knowledge of Performance |

| KR | Knowledge of Result |

| LCnp | Length of the Cycle of Non-Paretic Limb |

| LCp | Length of the Cycle of Paretic Limb |

| LDCW | Long Distance Corridor Walk |

| LLFDI | Late Life Function and Disability Index |

| LOS | Limit Of Stability |

| MAS | Modified Ashworth Scale |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| N | Total Sample |

| NEA | Normalized Error Area |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OCGT | Overground Conventional Gait Training Group |

| Ppeak | Peak Work Rate |

| PBWS | Partial Body Weight Supported |

| PD | Parkinson´s Disease |

| RATE | Robotics Assisted Treadmill Exercise |

| RCTs | Randomised Controlled Trials |

| RERpeak | Peak Respiratory Exchange Ratio |

| Rfpeak | Peak Respiratory Rate |

| ROM | Range of Movement |

| SD | Standar Deviation |

| STFnp | Stance Phase of the Non-Paretic Limb |

| STFp | Stance Phase of the Paretic Limb |

| STP | Stance Time Period |

| SWFnp | Swing Phase of the Non-Paretic Limb |

| SWFp | Swing Phase of the Paretic Limb |

| Terr | Normalized Error in the Stride Period |

| TUG test | Timed Up and Go |

| UPDRS | United Parkinson´s Disease Rating Scale |

| VEpeak | Peak Ventilation Rate |

References

- Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Ridao-Fernández, C.; Ojeda, J.; Benítez-Lugo, M.; Sevillano, J.L. Reliability and validity study of the Chamorro Assisted Gait Scale for people with sprained ankles, walking with forearm crutches. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Rebollo-Roldán, J.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.J.; Chillón-Martínez, R.; Suárez-Serrano, C. Design and validation of GCH System 1.0 which measures the weight-bearing exerted on forearm crutches during aided gait. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittle, M.W. Gait Analysis: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, MS, USA, 2003; pp. 140–142. ISBN 9780702039225. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Noort, J.C.; Steenbrink, F. Real time visual feedback for gait retraining: Toward application in knee osteoarthritis. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2015, 53, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druzbicki, M.; Guzik, A.; Przysada, G.; Kwolek, A.; Brzozowska-Magoń, A. Efficacy of gait training using a treadmill with and without visual biofeedback in patients after stroke: A randomized study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 47, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agresta, C.; Hall, J. Gait Retraining for Injured and Healthy Runners using Augmented Feedback: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 45, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Kim, Y.; Cha, Y.; In, T.; Hur, Y.; Chung, Y. Effects of gait training with a cane and an augmented pressure sensor for enhancement of weight bearing over the affected lower limb in patients with stroke : A randomized controlled pilot study. Clin. Rehabil. 2015, 29, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakov, E. Gait rehabilitation: A new biofeedback device for monitoring and enhancing weight-bearing over the affected lower limb. Eura Medic. 2007, 43, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Basta, D.; Rossi-Izquierdo, M.; Soto-Varela, A.; Greters, M.E.; Bittar, R.S.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Eckardt, R.; Harada, T.; Goto, F.; Ogawa, K.; et al. Efficacy of a vibrotactile neurofeedback training in stance and gait conditions for the treatment of balance deficits: A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Otol. Neurotol. 2011, 32, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanotto, D.; Rosati, G.; Spagnol, S.; Stegall, P.; Agrawal, S.K. Effects of Complementary Auditory Feedback in Robot-Assisted Lower Extremity Motor Adaptation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2013, 21, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, N.A.; Glass, N.A.; Teran-Yengle, P.; Singh, B.; Wallace, R.B.; Yack, H.J. Intensive Gait Training for Older Adults with Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 94, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanhoe-Mahabier, W.; Allum, J.H.; Pasman, E.P.; Overeem, S.; Bloem, B.R. The effects of vibrotactile biofeedback training on trunk sway in Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, R.; Rodríguez, B.; Barcia, B.; Souto, S.; Chouza, M.; Martínez, S. Generalidades sobre Feedback (o retroalimentación). Fisioterapia 1998, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ochi, M.; Wada, F.; Saeki, S.; Hachisuka, K. Gait training in subacute non-ambulatory stroke patients using a full weight-bearing gait-assistance robot: A prospective, randomized, open, blinded-endpoint trial. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 353, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinzaños Fresnedo, J.; Sahagún Olmos, R.C.; León Hernández, S.R.; Pérez Zavala, R.; Quiñones Uriostegui, I.; Solano Salazar, C.J.; Cruz Lira, R.T.; Tinajero Santana, M.C. Efectos a corto plazo del entrenamiento de la marcha en una órtesis robótica (Lokomat®) con retroalimentación auditiva en pacientes con lesión medular incompleta crónica. Rehabilitacion 2015, 49, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, O.; de Bruin, E.D.; Schindelholz, M.; Schuster-Amft, C.; de Bie, R.A.; Hunt, K.J. Efficacy of Feedback-Controlled Robotics-Assisted Treadmill Exercise to Improve Cardiovascular Fitness Early After Stroke. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2015, 39, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baram, Y.; Lenger, R. Gait Improvement in Patients with Cerebral Palsy by Visual and Auditory Feedback. Neuromodulation: Technol. Neural Interface 2012, 15, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasileiro, A.; Gama, G.; Trigueiro, L.; Ribeiro, T.; Silva, E.; Galvão, É.; Lindquist, A. Influence of visual and auditory biofeedback on partial body weight support treadmill training of individuals with chronic hemiparesis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 51, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Byl, N.; Zhang, W.; Coo, S.; Tomizuka, M. Clinical impact of gait training enhanced with visual kinematic biofeedback: Patients with Parkinson’s disease and patients stable post stroke. Neuropsychologia 2015, 79, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.A.; Takacs, J.; Hart, K.; Massong, E.; Fechko, K.; Biegler, J. Comparison of mirror, raw video, and real-time visual biofeedback for training toe-out gait in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki, K.I.; Kim, M.S.; Moon, Y.; Choi, J.D. Effects of auditory feedback during gait training on hemiplegic patients’ weight bearing and dynamic balance ability. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsitz, L.A.; Lough, M.; Niemi, J.; Travison, T.; Howlett, H.; Manor, B. A shoe insole delivering subsensory vibratory noise improves balance and gait in healthy elderly people. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Tamawy, M.; Darwish, M.; Khallaf, M. Effects of augmented proprioceptive cues on the parameters of gait of individuals with Parkinson′s disease. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2012, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.; Mountain, G.; Hammerton, J. A review of the evidence underpinning the use of visual and auditory feedback for computer technology in post-stroke upper-limb rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thikey, H.; Grealy, M.; van Wijck, F.; Barber, M.; Rowe, P. Augmented visual feedback of movement performance to enhance walking recovery after stroke: Study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials 2012, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.C.; DeLuke, L.; Buerba, R.; Fan, R.E.; Zheng, Y.J.; Leslie, M.P.; Baumgaertner, M.R.; Grauer, J.N. Haptic biofeedback for improving compliance with lower-extremity partial weight bearing. Orthopedics 2014, 37, e993–e998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Sevillano, J.L.; Ridao-Fernández, C. A compact forearm crutch based on force sensors for aided gait: Reliability and validity. Sensors 2016, 16, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, D.H.; Bech, S.; Begault, D.R.; Adelstein, B.D. The relative importance of visual, auditory, and haptic information for the user’s experience of mechanical switches. Perception 2009, 38, 1560–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefmann, S.; Russo, R.; Hillier, S. The effectiveness of robotic-assisted gait training for paediatric gait disorders: Systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.A.; Chevidikunnan, M.F.; Khan, F.R.; Gaowgzeh, R.A. Effectiveness of knowledge of result and knowledge of performance in the learning of a skilled motor activity by healthy young adults. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1482–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Sherrington, C.; Maher, C.G. Evidence for physiotherapy practice: A survey of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Aust. J. Physiother. 2002, 48, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamato, T.P.; Maher, C.; Koes, B.; Moseley, A. The PEDro scale had acceptably high convergent validity, construct validity, and interrater reliability in evaluating methodological quality of pharmaceutical trials. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.; Maher, C.; Moseley, A. PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man Ther. 2000, 5, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Academia and Clinic Annals of Internal Medicine Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annu. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, P.; Nieuwboer, A.; Dorfman, M.; Ferrari, A.; Gazit, E.; Canning, C.G.; Rocchi, L.; Chiari, L.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Mirelman, A. Feasibility and effects of home-based smartphone-delivered automated feedback training for gait in people with Parkinson’s disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2016, 22, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khallaf, M.E.; Gabr, A.M.; Fayed, E.E. Effect of Task Specific Exercises, Gait Training, and Visual Biofeedback on Equinovarus Gait among Individuals with Stroke: Randomized Controlled Study. Neurol. Res. Int. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Mak, M.K.Y. Balance and Gait Training with Augmented Feedback Improves Balance Confidence in People with Parkinson’s Disease. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2014, 28, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sungkarat, S.; Fisher, B.E.; Kovindha, A. Efficacy of an insole shoe wedge and augmented pressure sensor for gait training in individuals with stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.H.; Kim, J.C.; Oh, D.W. Effects of a novel walking training program with postural correction and visual feedback on walking function in patients with post-stroke hemiparesis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 2581–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzetzis, G.; Votsis, E.; Kourtessis, T. The effect of different corrective feedback methods on the outcome and self confidence of young athletes. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2008, 7, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sardini, E.; Serpelloni, M.; Lancini, M. Wireless Instrumented Crutches for Force and Movement Measurements for Gait Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2015, 64, 3369–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, N.; Jacuinde, G. Design and Construction of a Novel Low-Cost Device to Provide Feedback on Manually Applied Forces. J. Orthop. Sport Phys. Ther. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstein, C.J.; Pohl, P.S.; Cardinale, C.; Green, A.; Scholtz, L.; Waters, C. Learning a partial-weight-bearing skill: Effectiveness of two forms of feedback. Phys. Ther. 1996, 76, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, C.G.; Lehmann, J. Training procedures and biofeedback methods to achieve controled partial weight bearing: An assessment. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1975, 56, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salmoni, A.W.; Schmidt, R.A. Knowledge of results and motor learning: A review and critical reappraisal. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigrist, R.; Rauter, G.; Riener, R.; Wolf, P. Augmented visual, auditory, haptic, and multimodal feedback in motor learning: A review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2013, 20, 21–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sülzenbrück, S.; Heuer, H. Type of visual feedback during practice influences the precision of the acquired internal model of a complex visuo-motor transformation. Ergonomics 2011, 54, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wu, T.; Xu, Z.; Gu, X. A pilot study of post-total knee replacement gait rehabilitation using lower limbs robot-assisted training system. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2014, 24, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloos, A.D.; Kegelmeyer, D.A.; White, S. The impact of different types of assistive devices on gait measures and safety in Huntington’s disease. PLoS ONE 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.S.; Russell, D.M.; Van Lunen, B.L.; Colberg, S.R.; Morrison, S. The impact of speed and time on gait dynamics. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2017, 54, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueiredo, P.R.P.; Silva, P.L.P.; Avelar, B.S.; Chagas, P.S.C.; Oliveira, L.C.P.; Mancini, M.C. Assessment of gait in toddlers with normal motor development and in hemiplegic children with mild motor impairment: A validity study. Brazilian J. Phys. Ther. 2013, 17, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Hsu, Y.L.; Shih, K.S.; Lu, J.M. Real-time gait cycle parameter recognition using a wearable accelerometry system. Sensors 2011, 11, 7314–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: All primary data were extracted from the referenced sources. Full search strategy available from the authors on request. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).