Abstract

Legionella is an underdiagnosed and underreported etiology of pneumonia. Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (LpSG1) is thought to be the most common pathogenic subgroup. This assumption is based on the frequent use of a urinary antigen test (UAT), only capable of diagnosing LpSG1. We aimed to explore the frequency of Legionella infections in individuals diagnosed with pneumonia and the performance of diagnostic methods for detecting Legionella infections. We conducted a scoping review to answer the following questions: (1) “Does nucleic acid testing (NAT) increase the detection of non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella compared to non-NAT?”; and (2) “Does being immunocompromised increase the frequency of pneumonia caused by non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella compared to non-immunocompromised individuals with Legionnaires’ disease (LD)?”. Articles reporting various diagnostic methods (both NAT and non-NAT) for pneumonia were extracted from several databases. Of the 3449 articles obtained, 31 were included in our review. The most common species were found to be L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae, and unidentified Legionella species appearing in 1.4%, 0.9%, and 0.6% of pneumonia cases. Nearly 50% of cases were caused by unspecified species or serogroups not detected by the standard UAT. NAT-based techniques were more likely to detect Legionella than non-NAT-based techniques. The identification and detection of Legionella and serogroups other than serogroup 1 is hampered by a lack of application of broader pan-Legionella or pan-serogroup diagnostics.

1. Introduction

Legionnaires’ disease (LD) is caused by various species of Legionella, a genus of intracellular bacteria primarily found in water and soil. LD refers to pneumonia caused by Legionella. Legionellosis refers to Legionella infections, regardless of the site of infection. Within this text, Legionellosis is used when the source of the information uses the same terminology. Clinical symptoms vary from a mild febrile illness to severe and life-threatening pneumonia [1]. Legionella is suspected to be underdiagnosed in community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to non-specific presenting symptoms and signs, and thus there is an under-recognition by treating clinicians [2]. Pneumonia is commonly treated empirically without pathogen identification unless there is progressive clinical deterioration leading to further investigations [3]. Legionella are fastidious organisms that require special media for culture, and the sensitivity of culture techniques is low [4]. These limitations in LD detection and diagnostics have resulted in up to 90% of LD diagnoses being missed [5].

In 2022, the World Health Organization reported the overall mortality by Legionnaires’ disease as 5–10% and as high as 40–80% in immunosuppressed individuals [1]. The incidence of disease is estimated to be ten to fifteen cases per million per year in Europe, Australia, and the USA [1]. In 2019, the Public Health Agency of Canada stated that under 100 cases of LD were reported per year in Canada [6]. However, provincial data suggest a higher number of cases within Canada, with Ontario reporting over 100 cases per year from 2013 to 2022 [7]. Furthermore, LD cases have seen an increase across North America, as noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the British Columbia CDC [8,9].

Diagnostic testing for Legionella is rarely performed in mild CAP in community or hospitalized individuals and is only undertaken in severely ill hospitalized patients once other avenues have been exhausted. However, despite guidelines recommending that patients requiring hospitalization for CAP be tested for Legionella among other pathogens that may not be responsive to empirical therapy, the narrow spectrum of applicability, the limitations of most Legionella diagnostics, and the previously low rate of testing often make this effort fruitless [3,10,11]. The CDC and the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disease (NCCID) recommend diagnostic testing for Legionella in outpatients failing antibiotic therapy, individuals requiring intensive care admission, immunocompromised individuals, individuals with recent travel history, or in the setting of a known Legionellosis outbreak [4,8,12]. In addition, the CDC recommends testing for Legionella in cases of healthcare-associated pneumonia, and the NCCID recommends testing when there have been recent changes in water quality [12,13]. A recent review indicated a 42% increase in LD in the 3 weeks following storms [14]. LD is a looming hazard with the continuing rise in tropical storm intensity due to climate change, increased susceptibility associated with growing numbers of immunocompromised individuals, and a global aging population [14,15,16]. Additionally, the shortening of winter and the increase in average winter temperatures extends periods of rain and warm weather, further contributing to the risk of LD [14,15,17,18,19].

Out of the 65 species of Legionella, only 25 are known to cause disease in humans [20]. L. pneumophila is generally considered to be the most common cause of LD, followed by L. longbeachae, which is the cause of around 50% of LD cases in Oceania [21,22,23]. All clinically relevant species of Legionella are primarily found in water except the soilborne L. longbeachae. Effective treatments for LD include fluoroquinolones and macrolides [24]. Empirical therapy for CAP frequently includes either a macrolide or fluoroquinolones; however, when LD is not suspected and not treated, such as in immunocompromised people or people living with HIV, the outcomes and prognosis are adversely affected [25,26].

A summary of the diagnostic methods of LD is provided in Table 1. In most countries, the BinaxNOW urinary antigen test (UAT) remains the primary diagnostic test, with a high sensitivity and quick turnaround time for only a single serogroup of L. pneumophila (serogroup 1) [12,13,27,28]. In general, culture is the gold standard but has low sensitivity, requires invasive procedures to obtain samples (bronchoalveolar lavage) or involves samples that are infrequently produced in the context of LD (sputum), and offers no speciation in Legionella [12,29,30,31].

Table 1.

Current Legionella diagnostic techniques outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (4) a.

The prevalence of Legionella, especially non-pneumophila and non-serogroup 1 pneumophila, is likely underreported due to infrequent sampling, the unavailability of diagnostic tools in medical facilities, difficulty collecting sputum, long turnaround times, and the fact that it is only studied in severe clinical presentations or an outbreak context [24,27,32]. In this scoping review, we aimed to describe (1) the incidence, prevalence, and frequency of Legionella infections in individuals diagnosed with pneumonia with and without immunocompromised conditions, (2) the distribution of Legionella species and serotypes among people diagnosed with Legionella, and (3) which diagnostic techniques were used in each study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type

We conducted a scoping review following the scoping review checklist to answer the following questions [33]:

- Does nucleic acid testing (NAT) increase the detection of non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella compared to non-NAT?

- Does immunocompromisation increase the frequency of pneumonia caused by non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella compared to non-immunocompromised individuals with LD?

The population, intervention/exposure, comparator, outcome, and timeframe (PICOT) table for our questions are shown below in Table 2.

Table 2.

PICOT table outlining our research questions.

2.2. Search Strategy

We created a search strategy following PRISMA guidelines and searched in the following databases between 22 December 2022, and 12 February 2023: PubMed, PubMed Central, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, Clinicaltrials.org, and LegionellaDB. The full review protocol can be found in the Supplementary Material labeled as Supplemental Materials S1. A timeframe was not included in the search. Our search queries, search strategies, and precise dates can be found in Supplementary Table S1. All searches were uploaded to Covidence [33], a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of systematic and other literature reviews [34].

2.3. Study Selection

We included studies that met all of the following criteria: (1) original research that reports data about the PICOT questions that can be used to calculate incidence, frequency, or prevalence of Legionella with a species or serogroup analysis; (2) comparative quantitation using multiple detection methods; (3) use of at least one NAT- and one non-NAT-based technique for diagnosis; (4) at least 5 cases of LD in the patient group. During the title and abstract screening, articles were included if there was an indication of clinical diagnosis of Legionella.

We excluded studies with the following criteria: (1) case reports or series of <5 patients; (2) studies missing serogroup or species analysis; (3) studies in which patients were only infected with L. pneumophila serogroup 1; (4) articles not available in English; (5) articles with no abstract; (6) articles examining environmental distribution; (7) ongoing trials; (8) studies not conducted on humans or using human samples; (9) non-pneumonic Legionellosis; (10) articles in which the diagnostic techniques are not reported.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two blinded reviewers using Covidence [34]. References that met all the inclusion criteria without exclusions were selected for full-text review and data extraction. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or with a third reviewer where necessary.

2.4. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from the included studies: (1) year of study; (2) country(ies) or continent where the study was conducted; (3) population under study; (4) sample size disaggregated by sex; (5) diagnostic techniques used; (6) brand of tests, if listed; (7) species or serogroups found; (8) immunosuppressive conditions; (9) comorbidities; (10) time of follow-up, if listed; (11) limitations, both recognized and unrecognized by original authors.

2.5. Data Synthesis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to report the frequency at which each serogroup or species was found clinically and the diagnostic testing used. Some studies were only eligible to describe the Legionella subgroup (i.e., species and/or serogroups) breakdown within a population, while other studies allowed for an analysis of the specific by-technique breakdown for each subgroup. Studies fulfilling the latter criterion were used to conduct an analysis on the testing positivity of different techniques. Furthermore, articles providing LD cases within a greater pneumonia context were subject to an analysis on their frequency within this context.

3. Results

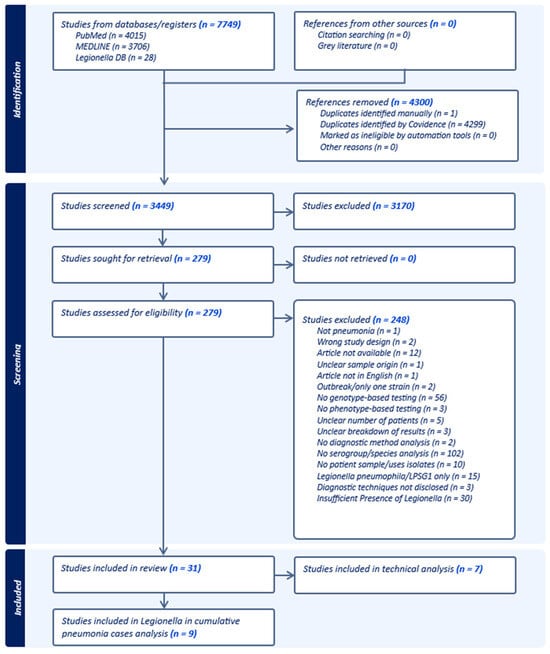

Of the 3449 article citations identified, we included 279 unique studies for full-text review and 31 in the analysis (Figure 1). Many excluded articles were excluded for multiple reasons. However, we can only list one reason in Covidence.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart depicting the screening process generated by Covidence [34].

Table 3 reports all the included articles, regions, populations studied, sample sizes, diagnostic test(s) used, and outcomes.

Table 3.

Summary of studies included in the scoping review.

When looking strictly at studies reporting cases of pneumonia, regardless of pathogen identification, the majority of LD cases were found to be caused by unserogrouped L. pneumophila, followed by L. longbeachae and unidentified species of Legionella depending on the population included, with other identified species and serogroups being few and far between (Table 4 and Table 5). Relative to the total pneumonia cases, the most prevalent subgroups of Legionella are L. pneumophila, L. longbeachae, and unknown species of Legionella appearing in 1.4% (summed up across all serogroups), 0.895%, and 0.627% of the population, respectively (Table 4). However, a significant portion of these are due to unserogrouped L. pneumophila (1.140%) and unknown Legionella species (0.627%). For many subgroups, there is a wide range in their frequency of diagnosis.

Table 4.

Breakdown of reported cases of Legionella subgroups relative to the cumulative population of pneumonia cases a.

Table 5.

Relative frequency of Legionella serogroups and species compared to total Legionella-positive cases in the literature a.

Relative representation of subgroups relative to total reported LD cases is as follows: Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, unserogrouped L. pneumophila, unspeciated Legionella, and L. longbeachae are the most common at 50.064%, 9.816%, 38.862%, and 0.482%, respectively (Table 5).

In studies involving national surveillance, the total population is reduced to either that of individuals diagnosed with pneumonia or LD, depending on the information provided in the study. Subgroups examined in only one eligible study have their frequencies marked with an asterisk (*) (Table 4 and Table 5).

Seven studies qualified for our technical analysis, which required a by-technique breakdown, including the reporting of all techniques performed on each sample instead of only listing the main technique used for diagnosis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Qualitative summary of diagnostics by Legionella species and serogroup, separated by technique a.

Additionally, studies were unclear about whether testing using the UAT was attempted for initial diagnoses of cases later found to be compatible with non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella but not LpSG1. Where it would normally be expected to give a negative result, it is unclear if the UAT was used at all, as the studies did not report its use either way.

4. Discussion

Our review found that most LD cases are caused by an unidentified species or serogroup of L. pneumophila. The emphasis on using a UAT that strictly detects LpSG1 as an initial test likely results in a significant number of missed cases [32,62,63]. Typically, culture-positive diagnoses are not subject to speciation or serogrouping or the species could not be identified for other reasons [36]. We found that almost 50% of LD cases are still caused by an unspecified species or a serogroup not detected by the standard UAT (Table 5). In general, the detection of the respiratory pathogen causing CAP is very low. Jain et al. found that only 38% of individuals with CAP were positive for pathogen detection [64].

The continued belief that LD is almost exclusively caused by L. pneumophila SG1 and the accompanying diagnostic practices leads to further missed diagnoses and increasingly discordant epidemiological data. In addition, the broad diagnostic coverage of Legionella is crucial, as the disease has been reported to be similar in both manifestations and outcomes across subgroups [38,65,66]. LD diagnosis is very narrow in scope and species identification is often not involved, further reinforcing the small pool of clinically relevant Legionella. While the BinaxNOW Legionella UAT has a rapid turnaround time, it is strictly capable of detecting L. pneumophila serogroup 1. The RIBOTEST Legionella, another UAT, is used exclusively in Japan and can detect Legionella pneumophila serogroups 1–15 and several other species at a sensitivity comparable to BinaxNOW Legionella’s rate of detection for LPSG1 strains suspended in saline solutions [67]. The other first-line diagnostic is culture, which is hampered by low sensitivity, takes several days, and has variable performance between laboratories. One potential hurdle to culture usage beyond the slow growth rate of Legionella species is the use of BCYE media without antibiotics, allowing the growth of other bacteria. Some newer products have been released on the market that may improve the landscape of Legionella diagnostics. Among these is the BioFire® FilmArray® Pneumonia (PN) Panel, which can detect up to 33 bacterial and viral targets (including Legionella pneumophila) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or sputum [68].

Based on our dataset, we found that NAT-based techniques had a higher frequency of Legionella positivity compared to non-NAT-based ones (Table 6). PCR remains unstandardized across institutions, as many groups use in-house primers and divergent protocols. Ideally, PCR should capture a diverse population of Legionella by using a multiplex panel of primers targeting genus-conserved sequences (e.g., 16S rRNA) and species-conserved sequences in some of the more common species of Legionella such as L. pneumophila and L. longbeachae, with some adjustments made based on locality. While costly, the adoption of sequencing into diagnostics would contribute to better surveillance of clinically relevant strains, changes in drug resistance, and mutations over time [69]. Of note, European countries have shifted towards sequence-based typing for Legionella rather than serogroup, which can be used to obtain sequences and typify from culture-negative samples [70].

One of the key issues in pneumonia treatment is that the etiology of CAP is rarely identified, and empirical treatments may not cover atypical bacteria, especially within the context of people living with HIV (PLHIV) [3,71]. In most scenarios, the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America do not recommend diagnosis until initial therapies have been exhausted, even suggesting the aversion of the UAT, unless the disease is severe [3,72]. Legionella cases requiring ICU admissions are associated with delayed urinary antigen testing and presumably Legionella testing in general [73]. Conversely, early concordant treatment reduces the probability of ICU admission [25,73]. Li et al. found that next-generation sequencing effectively detected fastidious organisms including Legionella in cases that culture failed to identify, even detecting pathogens when culture test results were negative, resulting in adjusted treatment in 55% of patients [74]. Thus, the delays and mistakes in Legionella identification are likely contributing to the high number of cases requiring hospitalization and intensive care.

Presumably, the reported case numbers of non-LpSG1 are inaccurate due to missed diagnoses. This is a conceivable scenario, as there are regional variations in species distribution and unidentified species were the third most common finding in our review [75]. Furthermore, many studies use culture or UAT for the initial diagnosis before further identification, only testing samples with other techniques when initial tests showed positive. Necessitating a positive result from these techniques introduces a bias toward the detected species or serogroups. Samples for culture are rare due to difficulties in obtaining bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum, while the UAT is over-selective [13,27,32,74]. Our findings show that the subgroups that warrant more deliberate monitoring are L. pneumophila regardless of serogroup, L. longbeachae, L. micdadei, and L. bozemanae (Table 4 and Table 5).

While it has been widely recognized that diagnosis of Legionella pneumonia is poor, Table 6 highlights the need for diagnostics to be more comprehensive. While accommodating the detection of all species of Legionella, the inter-study and presumably inter-lab consistency of PCR is unknown. The information included in our dataset suggests that PCR and DNA probes had a higher frequency of positivity, regardless of Legionella subgroup (Table 6). Of note, DNA probes were only used in one study, and of the studies that reported which type of PCR was used, all used real-time PCR. The difficulty in recovering respiratory samples further encourages the merits of testing multiple specimens. Without having to develop new techniques or products to detect Legionella in patient samples, there is a benefit in adopting a more comprehensive diagnostic regimen as conducted by Pasculle et al. and Decker et al. [24,53,73,76]. However, these are not without the drawback of a higher rate of false positives.

Beyond the consequences of a delayed diagnosis and impeded timely concordant treatment, limitations of Legionella diagnostics exacerbate the issue further by also delaying the recognition of outbreaks [5,77,78,79,80]. Identifying an outbreak of Legionella is crucial, as typical outbreak strategies such as isolation of cases will not reduce cases, and the medium by which Legionella is contracted (water) makes outbreaks very likely. The delay also contributes to increasing the mortality rate, as in immunosuppressed individuals the mortality rate can be up to 80% in infections across a range of different species of Legionella if left untreated [5,81]. Furthermore, up to 90% of Legionella infections are missed even in environments that are equipped for diagnosis and the increasing mortality rate, warranting an increase in testing frequency [5]. Our findings are in agreement with Decker et al., who found that systematically testing for Legionella in people diagnosed with pneumonia using two diagnostic techniques indicated that Legionella diagnoses had been underreported [76].

An opportunity for further research is to determine if PLHIV or other forms of immunosuppression have a higher susceptibility to specific subgroups of Legionella. While we had sought to investigate this, the lack of reporting of Legionella cases impeded our efforts in doing so. Head et al. found that 36% of PLHIV were coinfected with Legionella [81]. In their study, approximately one-third of the Legionella infections were caused by L. pneumophila, none of which were LPSG1 [81]. However, it is unclear if these proportions are due to geographical factors or the presence of HIV. Sivagnanam et al. found that 31% and 47% of their American transplant recipient cohort were infected with L. micdadei and L. pneumophila, respectively [60]. These studies emphasize the need to diversify diagnostic methods, especially in the immunocompromised population.

A limitation of our study is that further analyses cannot be performed because of a lack of information regarding the specific tests used, the differences in populations tested, the sample storage conditions, and that patients received inconsistent testing. Furthermore, studies used different techniques as their standards, only subjecting samples to further diagnosis with an initial positive result. Despite the heterogeneity in testing protocols and specific primers, PCR provided positive results in most tests. We were also unable to draw any conclusions about the effect of geographical distribution and regional testing conventions with the number of studies included in our review. Additionally, researchers are more likely to publish results that reveal particularly high or low prevalence, which may cause intermediate cases to be unrepresented within the literature. This was also the reasoning behind our inclusion criteria “at least 5 cases of LD in the patient group”, as articles reporting very few cases tended to be case reports/series or looking at isolated cases of LD without the generalized pneumonia context. Additionally, among the 30 studies that were excluded for the insufficient presence of Legionella, 15 found 0 cases of LD and 2 studies found 4 cases. The remaining 13 studies were also excluded for additional reasons, most frequently a lack of species/serogroup analysis and/or the absence of an NAT-based diagnosis.

In conclusion, the real epidemiology of Legionella infections is unclear due to the lack of an adequate diagnostic test that identifies other non-pneumophila serogroup 1 Legionella and different criteria on who, when, and how to diagnose Legionella [22,23,29,32,80]. It is essential to isolate strains and carry out epidemiological research studies using whole-genome sequencing to identify and track circulating strains of Legionella for future diagnostic test development, strains of concern, and clinical guideline updates.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens13100857/s1, Table S1. Search history, databases, and search terms (Supplementary material S1).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.H., Y.K. and Z.V.R. Methodology: R.H. and Z.V.R. Investigation: R.H., A.H. and Z.V.R. Validation: Y.K. and Z.V.R. Formal Analysis: all authors. Data curation: R.H. and A.H. Writing—Original Draft: R.H. and A.H. Writing—Review and Editing: S.A.L., C.T., D.A., Y.K. and Z.V.R. Resources: Z.V.R. Visualization: R.H., A.H., Y.K. and Z.V.R. Supervision: Y.K. and Z.V.R. Project Administration: Z.V.R. Funding Acquisition: Z.V.R. and Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Christopher Spitzke Critical Illness Research Endowment Fund (Y.K., grant number N/A). This research was also supported, in part, by the Canada Research Chairs Program for Z.V.R. (award # 950-232963). R.H. and A.H. received scholarships for their master studies funded by the CRC Program funding provided to Z.V.R. and R.H. also received the University of Manitoba Rady Faculty of Health Sciences Graduate Studentship. The funders did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of this paper, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mariana Herrera Diaz for her methodological guidance during the abstract and full-text reviewing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Legionellosis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/legionellosis (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Phin, N.; Parry-Ford, F.; Harrison, T.; Stagg, H.R.; Zhang, N.; Kumar, K.; Lortholary, O.; Zumla, A.; Abubakar, I. Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Legionnaires’ Disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e45–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Testing for Legionella|Legionella|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/php/laboratories/index.html (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Tanimoto, T.; Takahashi, K.; Crump, A. Legionellosis in Japan: A Self-Inflicted Wound? Intern. Med. 2021, 60, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada Legionella. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/legionella.html (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Public Health Ontario Legionellosis (Legionella, Legionnaires Disease)|Public Health Ontario. Available online: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/diseases-and-conditions/infectious-diseases/respiratory-diseases/legionellosis (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Legionnaires Disease History, Burden, and Trends|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/about/history.html (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- BC Centre for Disease Control. Communicable Disease Control. Chapter I—Management of Specific Diseases Legionella Outbreak Investigation and Control JULY 2021; BC CDC: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, J.; Buising, K. Could It Be Legionella? Aust. Fam. Physician 2008, 37, 812–815. [Google Scholar]

- File, T.M. Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults Who Require Hospitalization. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-community-acquired-pneumonia-in-adults-who-require-hospitalization?search=legionella&source=search_result&selectedTitle=6~102&usage_type=default&display_rank=6 (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases Legionella. Available online: https://nccid.ca/debrief/legionella/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Legionella (Legionnaires’ Disease and Pontiac Fever). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/index.html (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Lynch, V.D.; Shaman, J. Waterborne Infectious Diseases Associated with Exposure to Tropical Cyclonic Storms, United States, 1996–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 1548–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, A. A Force of Nature: Hurricanes in a Changing Climate. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/news/3184/a-force-of-nature-hurricanes-in-a-changing-climate/ (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Cohen, M.K.; Kent, C.K.; King, P.H.; Gottardy, A.J.; Leahy, M.A.; Spriggs, S.R.; Velarde, A.; Yang, T.; Starr, T.M.; Yang, M.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance of Waterborne Disease Outbreaks Associated with Drinking Water-United States, 2015–2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR Editorial and Production Staff. (Serials) MMWR Editorial Board. Acting Lead. Health Communication Specialist CONTENTS. 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/ss/pdfs/ss7301a1-H.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Barskey, A.E.; Derado, G.; Edens, C. Rising Incidence of Legionnaires’ Disease and Associated Epidemiologic Patterns, United States, 1992–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, 28, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Y. Effects of Climate Changes and Road Exposure on the Rapidly Rising Legionellosis Incidence Rates in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, B.; Payne Hallström, L.; Robesyn, E.; Ursut, D.; Zucs, P.; on behalf of ELDSNet (European Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance Network). Travel-Associated Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe, 2010. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Legionella Control International Ltd. How Many Legionella Species Exist & Which Ones Cause Legionnaires’ Disease? Available online: https://legionellacontrol.com/legionella/legionella-species/ (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Waller, C.; Freeman, K.; Labib, S.; Baird, R. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Legionellosis in Northern Australia, 2010–2021. Commun. Dis. Intell. 2022, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care Legionellosis—Surveillance Case Definition. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/legionellosis-surveillance-case-definition?language=en (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- The Prevention of Legionellosis in New Zealand Guidelines for the Control of Legionella Bacteria; The Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012.

- Viasus, D.; Gaia, V.; Manzur-Barbur, C.; Carratalà, J. Legionnaires’ Disease: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C.H.; Grove, D.I.; Looke, D.F.M. Delay in Appropriate Therapy of Legionella Pneumonia Associated with Increased Mortality. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 15, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolter, N.; Carrim, M.; Cohen, C.; Tempia, S.; Walaza, S.; Sahr, P.; de Gouveia, L.; Treurnicht, F.; Hellferscee, O.; Cohen, A.L.; et al. Legionnaires’ Disease in South Africa, 2012–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2016, 22, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, B.A.; Burillo, A.; Bouza, E. Legionnaires’ Disease. Lancet 2016, 387, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercante, J.W.; Winchell, J.M. Current and Emerging Legionella Diagnostics for Laboratory and Outbreak Investigations. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 95–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, L.R.; Hammitt, L.L.; Murdoch, D.R.; O’Brien, K.L.; Scott, J.A. Procedures for Collection of Induced Sputum Specimens from Children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, S140–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maze, M.J.; Slow, S.; Cumins, A.-M.; Boon, K.; Goulter, P.; Podmore, R.G.; Anderson, T.P.; Barratt, K.; Young, S.A.; Pithie, A.D.; et al. Enhanced Detection of Legionnaires’ Disease by PCR Testing of Induced Sputum and Throat Swabs. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.Y.W.; Johnsson, A.T.A.; Iversen, A.; Athlin, S.; Özenci, V. Evaluation of Four Lateral Flow Assays for the Detection of Legionella Urinary Antigen. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinjo, T.; Ito, A.; Ishii, M.; Komiya, K.; Yamasue, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Imamura, Y.; Iwanaga, N.; Tateda, K.; Kawakami, K. National Survey of Physicians in Japan Regarding Their Use of Diagnostic Tests for Legionellosis. J. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 28, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2023.

- Alexiou-Daniel, S.; Stylianakis, A.; Papoutsi, A.; Zorbas, I.; Papa, A.; Lambropoulos, A.F.; Antoniadis, A. Application of Polymerase Chain Reaction for Detection of Legionella Pneumophila in Serum Samples. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 1998, 4, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauté, J. The European Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance Network Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe, 2011 to 2015. Euro Surveill 2017, 22, 30566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, P.; Papazian, L.; Drancourt, M.; La Scola, B.; Auffray, J.-P.; Raoult, D. Ameba-Associated Microorganisms and Diagnosis of Nosocomial Pneumonia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, R.L.; Pollock, K.G.J.; Lindsay, D.S.J.; Anderson, E. Comparison of Legionella Longbeachae and Legionella Pneumophila Cases in Scotland; Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment and Public Health Response. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 65, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederen, B.M.W.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.; Peeters, M.F. Utility of Real-Time PCR for Diagnosis of Legionnaires’ Disease in Routine Clinical Practice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederen, B.M.W.; Van Der Eerden, M.M.; Vlaspolder, F.; Boersma, W.G.; Kluytmans, J.A.J.W.; Peeters, M.F. Detection of Respiratory Viruses and Legionella Spp. by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction in Patients with Community Acquired Pneumonia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 41, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elverdal, P.L.; Jørgensen, C.S.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Uldum, S.A. Two Years’ Performance of an in-House ELISA for Diagnosis of Legionnaires’ Disease: Detection of Specific IgM and IgG Antibodies against Legionella Pneumophila Serogroup 1, 3 and 6 in Human Serum. J. Microbiol. Methods 2013, 94, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Hashemzadeh, M.; Amin, M.; Moosavian, M.; Nashibi, R.; Mehraban, Z. Occurrence of the Legionella Species in the Respiratory Samples of Patients with Pneumonia Symptoms from Ahvaz, Iran; First Detection of Legionella Cherrii. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 7141–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenman, H.L.; Chambers, S.T.; Pithie, A.D.; MacDonald, S.L.S.; Hegarty, J.M.; Fenwick, J.L.; Maze, M.J.; Metcalf, S.C.L.; Murdoch, D.R. Legionnaires’ Disease Caused by Legionella Longbeachae: Clinical Features and Outcomes of 107 Cases from an Endemic Area. Respirology 2016, 21, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, S.; Søgaard, O.S.; Fine, M.J.; Østergaard, L. The Relationship between Diagnostic Tests and Case Characteristics in Legionnaires’ Disease. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 41, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.A. European Working Group for Legionella Infections Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe 2000–2002. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.A.; Ricketts, K.D.; Collective on behalf of the European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe 2007–2008. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.M.; Jeong, Y.; Sohn, J.W.; Kim, M.J. Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Legionella Species. Mol. Cell Probes 2015, 29, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lever, F.; Joseph, C.A.; on behalf of the European Working Group for Legionella Infections (EWGLI). Travel Associated Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe in 2000 and 2001. Eurosurveillance 2003, 8, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Abraham, W.H.; Fallon, R.J. Detection of Mip Gene by PCR for Diagnosis of Legionnaires’ Disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1994, 32, 3068–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löf, E.; Chereau, F.; Jureen, P.; Andersson, S.; Rizzardi, K.; Edquist, P.; Kühlmann-Berenzon, S.; Galanis, I.; Schönning, C.; Kais, M.; et al. An Outbreak Investigation of Legionella Non-Pneumophila Legionnaires’ Disease in Sweden, April to August 2018: Gardening and Use of Commercial Bagged Soil Associated with Infections. Euro Surveill 2021, 26, 1900702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniwa, K.; Taguchi, Y.; Ito, Y.; Mishima, M.; Yoshida, S. Retrospective Study of 30 Cases of Legionella Pneumonia in the Kansai Region. J. Infect. Chemother. 2006, 12, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, D.R.; Walford, E.J.; Jennings, L.C.; Light, G.J.; Schousboe, M.I.; Chereshsky, A.Y.; Chambers, S.T.; Town, G.I. Use of the Polymerase Chain Reaction to Detect Legionella DNA in Urine and Serum Samples from Patients with Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 23, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasculle, A.W.; Veto, G.E.; Krystofiak, S.; McKelvey, K.; Vrsalovic, K. Laboratory and Clinical Evaluation of a Commercial DNA Probe for the Detection of Legionella Spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1989, 27, 2350–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouderoux, C.; Ginevra, C.; Descours, G.; Ranc, A.-G.; Beraud, L.; Boisset, S.; Magand, N.; Conrad, A.; Bergeron-Lafaurie, A.; Jarraud, S.; et al. Slowly or Nonresolving Legionnaires’ Disease: Case Series and Literature Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, P.C.; Slow, S.; Chambers, S.T.; Cameron, C.M.; Balm, M.N.; Beale, M.W.; Blackmore, T.K.; Burns, A.D.; Drinković, D.; Elvy, J.A.; et al. The Burden of Legionnaires’ Disease in New Zealand (LegiNZ): A National Surveillance Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhou, H.; Ren, H.; Shi, W.; Jin, H.; Jiang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Combined Use of Real-Time PCR and Nested Sequence-Based Typing in Survey of Human Legionella Infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 2016, 144, 2006–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricketts, K.D.; Joseph, C. Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe 2003–2004. Eurosurveillance 2005, 10, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricketts, K.; Joseph, C.A.; Yadav, R.; Collective on behalf of the European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Travel-Associated Legionnaires’ Disease in Europe in 2008. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scaturro, M.; Rota, M.C.; Caporali, M.G.; Girolamo, A.; Magoni, M.; Barberis, D.; Romano, C.; Cereda, D.; Gramegna, M.; Piro, A.; et al. A Community-Acquired Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreak Caused by Legionella Pneumophila Serogroup 2: An Uncommon Event, Italy, August to October 2018. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagnanam, S.; Podczervinski, S.; Butler-Wu, S.M.; Hawkins, V.; Stednick, Z.; Helbert, L.A.; Glover, W.A.; Whimbey, E.; Duchin, J.; Cheng, G.; et al. Legionnaires’ Disease in Transplant Recipients: A 15-year Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Referral Center. Transplant. Infect. Dis. 2017, 19, e12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateda, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Ishii, Y.; Furuya, N.; Ohno, A.; Miyazaki, S.; Yamaguchi, K. Serum Cytokines in Patients with Legionella Pneumonia: Relative Predominance of Th1-Type Cytokines. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1998, 5, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EIKEN CHEMICAL Co., Ltd. Rapid Testing|Products|EIKEN CHEMICAL Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.eiken.co.jp/en/products/rapid_test/index.html (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Congestrì, F.; Morotti, M.; Vicari, R.; Pedna, M.F.; Sparacino, M.; Torri, A.; Bertini, S.; Fantini, M.; Sambri, V. Comparative Evaluation of the Novel IMMUNOCATCHTM Streptococcus Pneumoniae (EIKEN CHEMICAL Co., Ltd.) Test with the Uni-GoldTM Streptococcus Pneumoniae Assay and the BinaxNOW® Streptococcus Pneumoniae Antigen Card for the Detection of Pneumococcal Capsular Antigen in Urine Samples. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Self, W.H.; Wunderink, R.G.; Fakhran, S.; Balk, R.; Bramley, A.M.; Reed, C.; Grijalva, C.G.; Anderson, E.J.; Courtney, D.M.; et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Requiring Hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N.Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, B.M.; Trajtman, A.; Rueda, Z.V.; Vélez, L.; Keynan, Y. Atypical Bacterial Pneumonia in the HIV-Infected Population. Pneumonia 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, M.R.; Murdoch, D.R.; Pithie, A.D. Legionnaires’ Disease Caused by Legionella Longbeachae and Legionella Pneumophila: Comparison of Clinical Features, Host-Related Risk Factors, and Outcomes. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 1405–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Fukuda, S.; Kusuki, M.; Watari, H.; Shimura, S.; Kimura, K.; Nishi, I.; Komatsu, M. Evaluation of Five Legionella Urinary Antigen Detection Kits Including New Ribotest Legionella for Simultaneous Detection of Ribosomal Protein L7/L12. J. Infect. Chemother. 2021, 27, 1533–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bioMérieux BioFire® FilmArray® Pneumonia (PN) Panel. Available online: https://www.biofiredx.com/products/the-filmarray-panels/filmarray-pneumonia/ (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Coscollá, M.; González-Candelas, F. Direct Sequencing of Legionella Pneumophila from Respiratory Samples for Sequence-Based Typing Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 2901–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginevra, C.; Lopez, M.; Forey, F.; Reyrolle, M.; Meugnier, H.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J.; Jarraud, S.; Molmeret, M. Evaluation of a Nested-PCR-Derived Sequence-Based Typing Method Applied Directly to Respiratory Samples from Patients with Legionnaires’ Disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- von Baum, H.; Ewig, S.; Marre, R.; Suttorp, N.; Gonschior, S.; Welte, T.; Lück, C. Community-Acquired Legionella Pneumonia: New Insights from the German Competence Network for Community Acquired Pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.M.; Binnicker, M.J.; Campbell, S.; Carroll, K.C.; Chapin, K.C.; Gilligan, P.H.; Gonzalez, M.D.; Jerris, R.C.; Kehl, S.C.; Patel, R.; et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, e1–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Russo, A.; Tiseo, G.; Cesaretti, M.; Guarracino, F.; Menichetti, F. Predictors of Intensive Care Unit Admission in Patients with Legionella Pneumonia: Role of the Time to Appropriate Antibiotic Therapy. Infection 2021, 49, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, J.; Hu, T.; Cheng, L.; Shang, W.; Yan, L. Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing on Antimicrobial Treatment in Immunocompromised Adults with Suspected Infections. World J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, S.T.; Slow, S.; Scott-Thomas, A.; Murdoch, D.R. Legionellosis Caused by Non-legionella Pneumophila Species, with a Focus on Legionella Longbeachae. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, B.K.; Harris, P.L.; Muder, R.R.; Hong, J.H.; Singh, N.; Sonel, A.F.; Clancy, C.J. Improving the Diagnosis of Legionella Pneumonia within a Healthcare System through a Systematic Consultation and Testing Program. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1289–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reller, L.; Weinstein, M.P.; Murdoch, D.R. Diagnosis of Legionella Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 36, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Eerden, M.M. Comparison between Pathogen Directed Antibiotic Treatment and Empirical Broad Spectrum Antibiotic Treatment in Patients with Community Acquired Pneumonia: A Prospective Randomised Study. Thorax 2005, 60, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falguera, M.; Ruiz-Gonzalez, A.; Schoenenberger, J.A.; Touzon, C.; Gazquez, I.; Galindo, C.; Porcel, J.M. Prospective, Randomised Study to Compare Empirical Treatment versus Targeted Treatment on the Basis of the Urine Antigen Results in Hospitalised Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Thorax 2010, 65, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, E.; Allara, E.; Patrucco, F.; Faggiano, F.; Hamid, F.; Balbo, P.E. Adherence to Guidelines for Hospitalized Community-Acquired Pneumonia over Time and Its Impact on Health Outcomes and Mortality. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2016, 11, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, B.M.; Trajtman, A.; Bernard, K.; Burdz, T.; Vélez, L.; Herrera, M.; Rueda, Z.V.; Keynan, Y. Legionella Co-Infection in HIV-Associated Pneumonia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 95, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).