The Effect of Nutrition on Aging—A Systematic Review Focusing on Aging-Related Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

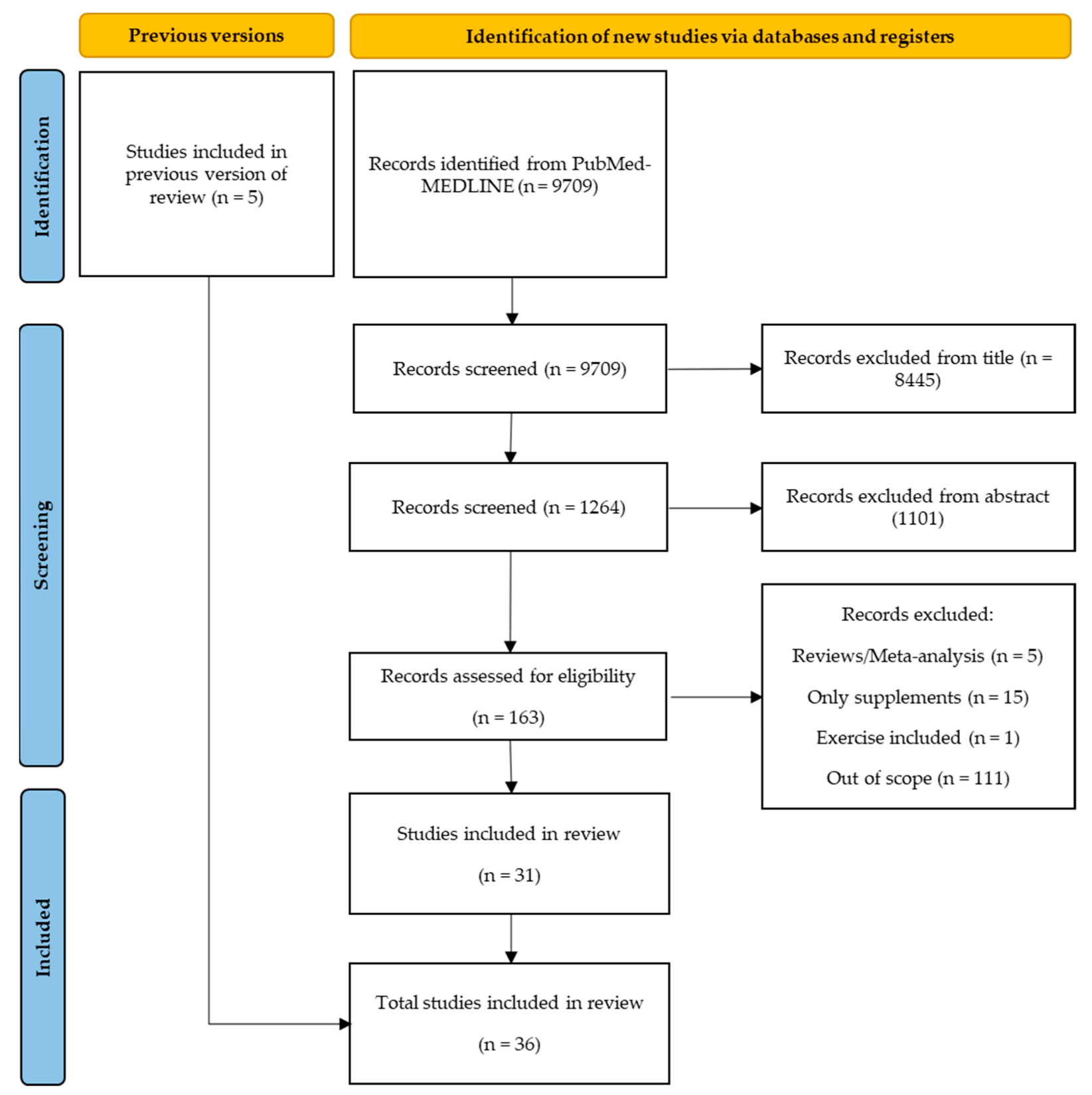

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.3.1. Study Design

3.3.2. Location

3.3.3. Setting

3.3.4. Sample Size and Study Population

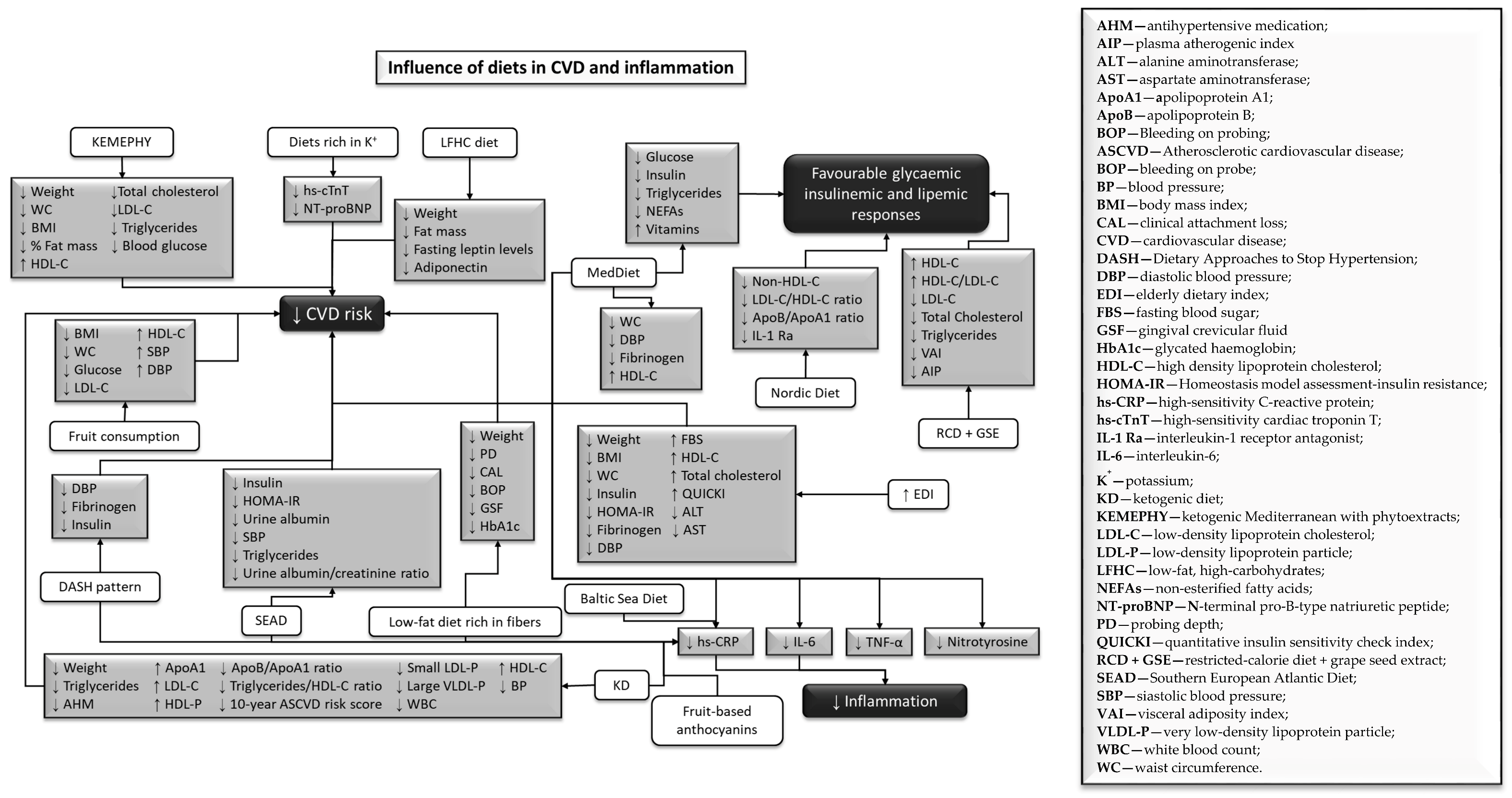

3.3.5. Influence of Different Types of Diet on Biomarkers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Partridge, L.; Gems, D. Mechanisms of aging: Public or private? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Austad, S.N. Why do we age? Nature 2000, 408, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, L.; Gems, D.; Charlesworth, B. The evolution of longevity primarily by the work of Bill. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 544–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD. World Population Ageing 2019; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robine, J.; Saito, Y.; Jagger, C. The relationship between longevity and healthy life expectancy. Qual Ageing 2009, 10, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Carding, S.R.; Christopher, G.; Kuh, D.; Langley-Evans, S.C.; McNulty, H. A holistic approach to healthy ageing: How can people live longer, healthier lives? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsman, D.; Belsky, D.W.; Gregori, D.; Johnson, M.A.; Dog, T.L.; Meydani, S.; Pigat, S.; Sadana, R.; Shao, A.; Griffiths, J.C. Healthy ageing: The natural consequences of good nutrition—A conference report. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, S15–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunan, J.R.; Watson, M.M.; Hagland, H.R.; Søreide, K. Molecular and biological hallmarks of ageing. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, e29–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging Europe PMC Funders Group. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinger, A.; Cho, W.C.; Ben-yehuda, A. Cancer and Aging—The Inflammatory Connection. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysokiński, A.; Sobów, T.; Kłoszewska, I.; Kostka, T. Mechanisms of the anorexia of aging—A review. Age 2015, 37, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, A.; Paterno, J.J.; Blasiak, J.; Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Inflammation and its role in age -related macular degeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 1765–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonté, F.; Girard, D.; Archambault, J.; Desmoulière, A. Skin Changes During Ageing. In Biochemistry and Cell Biology of Ageing: Part II Clinical Science; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.M.; Danaei, G.; Pelizzari, P.; Lin, J.K.; Cowan, M.J.; Stevens, G.A.; Farzadfar, F.; Khang, Y.-H.; Lu, Y.; Riley, L.M.; et al. The Age Associations of Blood Pressure, Cholesterol, and Glucose Analysis of Health Examination Surveys from International Populations. Circulation 2012, 125, 2204–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaaldini, M.M.; Marzetti, E.; Picca, A.; Murlasits, Z. Biochemical Pathways of Sarcopenia and Their Modulation by Physical exercise: A Narrative Review. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Chen, Y.; Hsieh, W.; Chiou, S.; Kao, C. Ageing and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010, 9, S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freid, V.M.; Bernstein, A.B.; Bush, M.A. Multiple Chronic Conditions Among Adults Aged 45 and Over: Trends Over the Past 10 Years. NCHS Data Briefs 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chiuve, S.E.; Mccullough, M.L.; Sacks, F.M.; Rimm, E.B. Healthy Lifestyle Factors in the Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease Among Men. Circulation 2006, 114, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.E.; Mainous, A.G., III; Matheson, E.M.; Everett, C.J. Impact of healthy lifestyle on mortality in people with normal blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and C-reactive protein. Eur. J. Precentive Cardiol. 2011, 20, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ageing: Healthy Ageing and Functional Ability 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/%0Aageing/healthy-ageing/en/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Mathers, J.C. Nutrition and ageing: Knowledge, gaps and research priorities. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.C.K.; Mathers, J.C.; Franco, O.H. Nutrition and healthy ageing: The key ingredients. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanner, S. Healthy ageing: The role of nutrition and lifestyle. Nurs. Resid. Care 2009, 11, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D. Health Benefits of Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrovolas, S.; Haro, J.M.; Mariolis, A.; Piscopo, S.; Valacchi, G.; Tsakountakis, N.; Zeimbekis, A.; Tyrovola, D.; Bountziouka, V.; Gotsis, E.; et al. Successful aging, dietary habits and health status of elderly individuals: A k -dimensional approach within the multi-national MEDIS study. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 60, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbete, C.; Schwingshackl, L.; Schulze, M.B. Evaluating Mediterranean diet and risk of chronic disease in cohort studies: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 33, 909–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Physical activity and healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 38, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Associations of smoking and alcohol consumption with healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021244473 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Garg, A.X.; Adhikari, N.K.J.; McDonald, H.; Rosas-Arellano, M.P.; Devereaux, P.J.; Beyene, J.; Sam, J.; Haynes, R.B. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: A systematic review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005, 293, 1223–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pedrero, L.; Ojeda-Rodríguez, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Zalba, G.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Marti, A. Ultra-processed food consumption and the risk of short telomeres in an elderly population of the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Project. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Inagaki, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Kaneko, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Takihara, T. Effect of daily intake of green tea catechins on cognitive function in middle-aged and older subjects: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Molecules 2020, 25, 4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Real, J.M.; Bulló, M.; Moreno-Navarrete, J.M.; Ricart, W.; Ros, E.; Estruch, R.; Salas-Salvadó, J. A mediterranean diet enriched with olive oil is associated with higher serum total osteocalcin levels in elderly men at high cardiovascular risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 3792–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortin, A.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R.; Lemieux, S.; Labonté, M.E.; Gingras, V. Comparison of a Mediterranean to a low-fat diet intervention in adults with type 1 diabetes and metabolic syndrome: A 6–month randomized trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fretts, A.M.; Howard, B.V.; Siscovick, D.S.; Best, L.G.; Beresford, S.A.; Mete, M.; Eilat-Adar, S.; Sotoodehnia, N.; Zhao, J. Processed meat, but not unprocessed red meat, is inversely associated with leukocyte telomere length in the Strong Heart Family Study. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Calzón, S.; Zalba, G.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Martínez, J.A.; Fitó, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; A Martínez-González, M.; Marti, A. Dietary inflammatory index and telomere length in subjects with a high cardiovascular disease risk from the PREDIMED-NAVARRA study: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses over 5 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Calzón, S.; Zalba, G.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Martínez, J.A.; Fitó, M.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; A Martínez-González, M.; Marti, A. Effects of the mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 on metabolomic profiles in elderly men and women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2015, 70, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Honig, L.S.; Schupf, N.; Lee, J.H.; Luchsinger, J.A.; Stern, Y.; Scarmeas, N. Mediterranean diet and leukocyte telomere length in a multi-ethnic elderly population. Age 2015, 37, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guallar-Castillón, P.; Oliveira, A.; Lopes, C.; López-García, E.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. The Southern European Atlantic Diet is associated with lower concentrations of markers of coronary risk. Atherosclerosis 2013, 226, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal, F.M.G.; Martínez, P.P.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Camargo, A.; Delgado-Casado, N.; Cruz-Teno, C.; Santos-Gonzalez, M.; Rodriguez-Cantalejo, F.; Castaño, J.P.; et al. Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 induces postprandial changes in p53 in response to oxidative DNA damage in elderly subjects. Age 2012, 34, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Rangel-Zúñiga, O.A.; Marín, C.; García-Rios, A.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Malagón, M.M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Pérez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Postprandial activation of P53-dependent DNA repair is modified by mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 in elderly subjects. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2014, 69, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernáez, Á.; Castañer, O.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Pintó, X.; Fitó, M.; Casas, R.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Atherothrombosis Biomarkers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 2000350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Paz-Graniel, I.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Barrubés, L.; Corella, D.; Muñoz-Martínez, J.; Romaguera, D.; Vioque, J.; Alonso-Gómez, Á.M.; et al. Fruit consumption and cardiometabolic risk in the PREDIMED-plus study: A cross-sectional analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1702–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilpiran, Y.; Darooghegi Mofrad, M.; Mozaffari, H.; Bellissimo, N.; Azadbakht, L. Adherence to dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) and Mediterranean dietary patterns in relation to cardiovascular risk factors in older adults. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 39, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanerva, N.; Loo, B.-M.; Eriksson, J.G.; Leiviskä, J.; Kaartinen, N.E.; Jula, A.; Männistö, S. Associations of the Baltic Sea diet with obesity-related markers of inflammation. Ann. Med. 2014, 46, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari-Soltani, S.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Imamura, F.; Forouhi, N.G. Prospective association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and hepatic steatosis: The Swiss CoLaus cohort study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Ishikado, A.; Morino, K.; Nishio, Y.; Ugi, S.; Kajiwara, S.; Kurihara, M.; Iwakawa, H.; Nakao, K.; Uesaki, S.; et al. A high-fiber, low-fat diet improves periodontal disease markers in high-risk subjects: A pilot study. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, R.J.H.; Henry, R.M.A.; Bekers, O.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Van Dongen, M.C.J.M.; Eussen, S.J.P.M.; Van Greevenbroek, M.; Kroon, A.A.; A Stehouwer, C.D.; Wesselius, A.; et al. Associations of 24-Hour Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion with Cardiac Biomarkers: The Maastricht Study. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Galbete, C.; Corella, D.; Toledo, E.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Genotype patterns at CLU, CR1, PICALM and APOE, cognition and Mediterranean diet: The Predimed-Navarra trial. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofrad, M.D.; Namazi, N.; Larijani, B.; Surkan, P.J.; Azadbakht, L. Association of the Elderly Dietary Index with cardiovascular disease risk factors in elderly men: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica-Parodi, L.; Amgalan, A.; Sultan, S.F.; Antal, B.; Sun, X.; Skiena, S.; Lithen, A.; Adra, N.; Ratai, E.-M.; Weistuch, C.; et al. Diet modulates brain network stability, a biomarker for brain aging, in young adults. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6170–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neth, B.J.; Mintz, A.; Whitlow, C.; Jung, Y.; Sai, S.; Register, T.C.; Kellar, D.; Lockhart, S.N.; Maldjian, J.; Heslegrave, A.J.; et al. Modified ketogenic diet is associated with improved cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile, cerebral perfusion, and cerebral ketone body uptake in older adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease: A pilot study. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 86, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Cenci, L.; Grimaldi, K.A. Effect of ketogenic mediterranean diet with phytoextracts and low carbohydrates/high-protein meals on weight, cardiovascular risk factors, body composition and diet compliance in Italian council employees. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanpuri, N.H.; Hallberg, S.J.; Williams, P.T.; McKenzie, A.L.; Ballard, K.D.; Campbell, W.W.; McCarter, J.P.; Phinney, S.D.; Volek, J.S. Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: An open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönknecht, Y.B.; Crommen, S.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Coenen, M.; Fimmers, R.; Holst, J.J.; Simon, M.; Stehle, P.; Egert, S. Acute Effects of Three Different Meal Patterns on Postprandial Metabolism in Older Individuals with a Risk Phenotype for Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1901035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Kestin, M.; Schwarz, Y.; Yang, P.; Hu, X.; Lampe, J.W.; Kratz, M. A low-fat high-carbohydrate diet reduces plasma total adiponectin concentrations compared to a moderate-fat diet with no impact on biomarkers of systemic inflammation in a randomized controlled feeding study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiainen, A.-M.; Männistö, S.; Blomstedt, P.A.; Moltchanova, E.; Perälä, M.-M.; E Kaartinen, N.; Kajantie, E.; Kananen, L.; Hovatta, I.; Eriksson, J. Leukocyte telomere length and its relation to food and nutrient intake in an elderly population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1290–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitupa, M.; Hermansen, K.; Savolainen, M.J.; Schwab, U.; Kolehmainen, M.; Brader, L.; Mortensen, L.S.; Cloetens, L.; Johansson-Persson, A.; Önning, G.; et al. Effects of an isocaloric healthy Nordic diet on insulin sensitivity, lipid profile and inflammation markers in metabolic syndrome—A randomized study (SYSDIET). J. Intern. Med. 2013, 274, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, R.; Parandoosh, M.; Khorsandi, H.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Tonekaboni, M.M.; Saidpour, A.; Babaei, H.; Ghorbani, A. Grape seed extract supplementation along with a restricted-calorie diet improves cardiovascular risk factors in obese or overweight adult individuals: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; Gonzalez-Guardia, L.; Rangel-Zuñiga, O.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Delgado-Casado, N.; Cruz-Teno, C.; Tinahones, F.J.; Villalba, J.M.; et al. Mediterranean diet supplemented with coenzyme Q 10 Modifies the expression of proinflammatory and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes in elderly men and women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2012, 67, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Esposito, A.; Rizzo, M.R.; Marfella, R.; Barbieri, M.; Paolisso, G. Mediterranean Diet, Telomere Maintenance and Health Status among Elderly. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Curtis, A.; Persichillo, M.; Sofi, F.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; De Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Ultra-processed food consumption is associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the Moli-sani Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, A.; De Vivo, I.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Prescott, J.; Hunter, D.J.; Rimm, E.B. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.C.; Lee, M.S.; Chiou, J.M.; Chen, T.F.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, J.H. Association of diet quality and vegetable variety with the risk of cognitive decline in Chinese older adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous-Bou, M.; Fung, T.T.; Prescott, J.; Julin, B.; Du, M.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.; Hu, F.B.; De Vivo, I. Mediterranean diet and telomere length in Nurses’ Health study: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2014, 349, g6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosario, V.A.D.; Chang, C.; Spencer, J.; Alahakone, T.; Roodenrys, S.; Francois, M.; Weston-Green, K.; Hölzel, N.; Nichols, D.S.; Kent, K.; et al. Anthocyanins attenuate vascular and inflammatory responses to a high fat high energy meal challenge in overweight older adults: A cross-over, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.; De Pergola, G. The Mediterranean Diet: Its definition and evaluation of a priori dietary indexes in primary cardiovascular prevention. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 69, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.T.; Chiuve, S.E.; McCullough, M.L.; Rexrode, K.M.; Logroscino, G.; Hu, F.B. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Guisado, J.; Muñoz-Serrano, A.; Alonso-Moraga, Á. Spanish Ketogenic Mediterranean diet: A healthy cardiovascular diet for weight loss. Nutr. J. 2008, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, H.A. The Regulation of the release of ketone bodies by the liver. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 1966, 4, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamsson, V.; Reumark, A.; Cederholm, T.; Vessby, B.; Risérus, U.; Johansson, G. What is a healthy Nordic diet? Foods and nutrients in the NORDIET study. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.; Freitas, H. Influence of metal resistant-plant growth-promoting bacteria on the growth of Ricinus communis in soil contaminated with heavy metals. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P.; Greenwood, D.C.; Tonstad, S.; Vatten, L.J.; Riboli, E.; Norat, T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2016, 353, i2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.; Fontaine, K.R. Ketogenic Diet and Health. OBM Integr. Complementary Med. 2020, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Hansson, G.K. Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 54, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannel, W.B.; Anderson, K.; Wilson, P.W.F. White Blood Cell Count and Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1992, 267, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Buring, J.E.; Shih, J.; Matias, M.; Hennekens, C.H. Prospective Study of C-Reactive Protein and the Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events Among Apparently Healthy Women. Circulation 1998, 98, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Moehl, K.; Ghena, N.; Schmaedick, M.; Cheng, A. Intermittent metabolic switching, neuroplasticity and brain health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.-C.; Heath, S.; Even, G.; Campion, D.; Sleegers, K.; Hiltunen, M.; Combarros, O.; Zelenika, D.; Bullido, M.J.; Tavernier, B.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and CR1 associated with Alzheimer’ s disease. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, D.; Abraham, R.; Hollingworth, P.; Sims, R.; Gerrish, A.; Hamshere, M.L.; Pahwa, J.S.; Moskvina, V.; Dowzell, K.; Williams, A.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants at CLU and PICALM associated with Alzheimer’ s disease. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, G.; Naj, A.C.; Beecham, G.W.; Wang, L.-S.; Buros, J.; Gallins, P.J.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Ertekin-Taner, N.; Fallin, M.D.; Friedland, R.; et al. Meta-analysis Confirms CR1, CLU, and PICALM as Alzheimer Disease Risk Loci and Reveals Interactions with APOE Genotypes. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, O.; Allen, M.; Jennette, K.; Carrasquillo, M.; Crook, J.; Serie, D.; Pankratz, V.S.; Palusak, R.; Nguyen, T.; Malphrus, K.; et al. Evaluation of memory endophenotypes for association with CLU, CR1, and PICALM variants in black and white subjects. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, S.; Bird, T.; Goate, A.; Farlow, M.R.; Diaz-Arrastia, R.; Bennett, D.A.; Graff-Radford, N.; Boeve, B.F.; Sweet, R.A.; Stern, Y.; et al. Genotype patterns at PICALM, CR1, BIN1, CLU, and APOE genes are associated with episodic memory. Neurology 2012, 78, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The SU.VI.MAX 2 Research Group; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Andreeva, V.; Lassale, C.; Ferry, M.; Jeandel, C.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function: A French study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Judd, S.; Letter, A.J.; Alexandrov, A.V.; Howard, G.; Nahab, F.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Moy, C.; Howard, V.J.; Kissela, B.; et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of incident cognitive impairment. Neurology 2013, 80, 1684–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.O.; Geda, Y.E.; Cerhan, J.; Knopman, D.S.; Cha, R.H.; Christianson, T.J.H.; Pankratz, V.S.; Ivnik, R.J.; Boeve, B.F.; O’Connor, H.M.; et al. Vegetables, Unsaturated Fats, Moderate Alcohol Intake, and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2010, 29, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarmeas, N.; Stern, Y.; Mayeux, R.; Manly, J.J.; Schupf, N.; Luchsinger, J.A. Mediterranean Diet and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Inagaki, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Kaneko, T.; Takihara, T. Effects of Daily Matcha and Caffeine Intake on Mild Acute Psychological Stress-Related Cognitive Function in Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, K.; Yamada, H.; Takuma, N.; Park, M.; Wakamiya, N.; Nakase, J.; Ukawa, Y.; Sagesaka, Y.M. Green Tea Consumption Affects Cognitive Dysfunction in the Elderly: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4032–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer-Carter, J.L.; Green, P.S.; Montine, T.J.; VanFossen, B.; Baker, L.D.; Watson, G.S.; Bonner, L.M.; Callaghan, M.; Leverenz, J.B.; Walter, S.K.; et al. Diet Intervention and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Neurol. 2011, 68, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, B.; Xu, W.; Collins, S.; Fratiglioni, L. Cognitive decline, dietary factors and gut—Brain interactions. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisardi, V.; Panza, F.; Seripa, D.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Vendemiale, G. Nutraceutical Properties of Mediterranean Diet and Cognitive Decline: Possible Underlying Mechanisms. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010, 22, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottero, V.; Potashkin, J.A. A Comparison of Gene Expression Changes in the Blood of Individuals Consuming Diets Supplemented with Olives, Nuts or Long-Chain Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Cherubini, A.; Bandinelli, S.; Bartali, B.; Corsi, A.; Lauretani, F.; Martin, A.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Senin, U.; Guralnik, J.M. Relationship of Plasma Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids to Circulating Inflammatory Markers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, N.; Parletta, N.; Milte, C.; Benassi-Evans, B.; Fenech, M.; Howe, P. Telomere shortening in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment may be attenuated with ω-3 fatty acid supplementation: A randomized controlled pilot study. Nutrition 2014, 30, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Epel, E.S.; Belury, M.A.; Andridge, R.; Lin, J.; Glaser, R.; Malarkey, W.B.; Hwang, B.S.; Blackburn, E. Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Oxidative Stress, and Leukocyte Telomere Length: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 28, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Daniele, N.; Noce, A.; Vidiri, M.F.; Moriconi, E.; Marrone, G.; Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli, M.; D’Urso, G.; Tesauro, M.; Rovella, V.; De Lorenzo, A. Impact of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome, cancer and longevity. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 8947–8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Deus Mendonça, R.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am. J. Hypertens. 2017, 30, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Deus Mendonça, R.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: The University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Suárez, A. Burden of cancer attributable to obesity, type 2 diabetes and associated risk factors. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2019, 92, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; de Castro, I.R.; Cannon, G. Increasing Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Likely Impact on Human Health: Evidence from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Fuster, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines: A link between obesity and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, M.; Le Roux, C.W.; Docherty, N. Morbidity and mortality associated with obesity. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saneei, P.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Azadbakht, L. Influence of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doostvandi, T.; Bahadoran, Z.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. Food intake patterns are associated with the risk of impaired glucose and insulin homeostasis: A prospective approach in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchau, B.; Zulet, M.A.; de Echávarri, A.G.; Hermsdorff, H.H.M.; Martínez, J.A. Dietary total antioxidant capacity is negatively associated with some metabolic syndrome features in healthy young adults. Nutrition 2010, 26, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, M.S.; Bissada, N.F.; Borawski, E. Obesity and Periodontal Disease in Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adults. J. Periodontol. 2003, 74, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Bianco, A.A.; Grimaldi, K.; Lodi, A.; Bosco, G. Long Term Successful Weight Loss with a Combination Biphasic Ketogenic Mediterranean Diet and Mediterranean Diet Maintenance Protocol. Nutrients 2013, 5, 5205–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, H.; Panchal, S.K.; Diwan, V.; Brown, L. Omega-3 fatty acids and metabolic syndrome: Effects and emerging mechanisms of action. Prog. Lipid Res. 2011, 50, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, T.M.S.; Bolognesi, C. Prediction of glucose and insulin responses of normal subjects after consuming mixed meals varying in energy, protein, fat, carbohydrate and glycemic index. J. Nutr. 1996, 126, 2807–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Ahluwalia, N.; Brouns, F.; Buetler, T.; Clement, K.; Cunningham, K.; Esposito, K.; Jönsson, L.S.; Kolb, H.; Lansink, M.; et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, S5–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarou, C.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Chrysohoou, C.; Andronikou, C.; Matalas, A.L. C-Reactive protein levels are associated with adiposity and a high inflammatory foods index in mountainous Cypriot children. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, V.D.F.; Schwab, U.; Kolehmainen, M.; Koenig, W.; Siloaho, M.; Poutanen, K.; Mykkänen, H.; Uusitupa, M. A diet high in fatty fish, bilberries and wholegrain products improves markers of endothelial function and inflammation in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism in a randomised controlled trial: The Sysdimet study. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2755–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herder, C.; Brunner, E.J.; Rathmann, W.; Strassburger, K.; Tabák, A.G.; Schloot, N.C.; Witte, D.R. Elevated levels of the anti-inflammatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist precede the onset of type 2 diabetes: The whitehall II study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luotola, K.; Pietilä, A.; Zeller, T.; Moilanen, L.; Kähönen, M.; Nieminen, M.S.; Kesäniemi, Y.A.; Blankenberg, S.; Jula, A.; Perola, M.; et al. Associations between interleukin-1 (IL-1) gene variations or IL-1 receptor antagonist levels and the development of type 2 diabetes. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 269, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, M.; Herder, C.; Kivimäki, M.; Jokela, M.; Roden, M.; Shipley, M.J.; Witte, D.R.; Brunner, E.J.; Tabák, A.G. Accelerated increase in serum interleukin-1 receptor antagonist starts 6 years before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Micha, R.; Wallace, S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Appel, L.J.; Van Horn, L. Components of a cardioprotective diet: New insights. Circulation 2011, 123, 2870–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsis, E.; Katus, H.A. Cardiac troponin level elevations not related to acute coronary syndromes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struthers, A.; Lang, C. The potential to improve primary prevention in the future by using BNP/N-BNP as an indicator of silent “pancardiac” target organ damage. Eur. Hear. J. 2007, 28, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, N.J.; Hanson, S.; Gutierrez, H.; Hooper, L.; Elliott, P.; Cappuccio, F.P. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013, 346, f1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Elia, L.; Barba, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Strazzullo, P. Potassium Intake, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mente, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Rangarajan, S.; McQueen, M.; Dagenais, G.; Wielgosz, A.; Lear, S.; Ah, S.T.L.; Wei, L.; Diaz, R.; et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet 2018, 392, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Potassium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Hu, E.A.; Rebholz, C.M. Ultra-processed food intake and mortality in the USA: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Campà, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Alvarez-Alvarez, I.; de Deus Mendonça, R.; De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019, 365, l1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.R. Reactive oxygen species and death: Oxidative DNA damage in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 648–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-González, M.; Gómez Díaz, C.; Navas, P.; Villalba, J.M. Modifications of plasma proteome in long-lived rats fed on a coenzyme Q10-supplemented diet. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.R.; Neužil, J.; Stocker, R. Cosupplementation with Coenzyme Q Prevents the Prpoxidant Effect of α-Tocopherol and Increases the Resistance of LDL to Transition Metal-Dependent Oxidation Initiation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernster, L.; Dallner, G. Biochemical and physiological aspects of ubiquinone function. Membr. Cell Biol. 1995, 1271, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, A.; Forster, M.J.; Sohal, R.S. Effects of Coenzyme Q10 and a-tocopherol administration on their tissue levels in the mouse: Elevation of mitochondrial a-tocopherol by Coenzyme Q10. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, H.; Andreyev, D.; Arriaga, E.A.; Thompson, L.D.V. Capillary electrophoresis reveals changes in individual mitochondrial particles associated with skeletal muscle fiber type and age. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2006, 61, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiles, J.L.; Huertas, J.R.; Battino, M.; Ramírez-Tortosa, M.C.; Cassinello, M.; Mataix, J.; Lopez-Frias, M.; Mañas, M. The intake of fried virgin olive or sunflower oils differentially induces oxidative stress in rat liver microsomes. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, J.R.; Battino, M.; Lenaz, G.; Mataix, F.J. Changes in mitochondrial and microsomal rat liver coenzyme Q9, and Q10 content induced by dietary fat and endogenous lipid peroxidation. FEBS Lett. 1991, 287, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C.; Urbano, G.; López-Jurado, M.; Nestares, T.; Gomez, M.C.; Mir, A.; Ros, E.; Mataix, J.; Gil, A. Extra-virgin olive oil increases the resistance of LDL to oxidation more than refined olive oil in free-living men with peripheral vascular disease. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Lane, D.; Levine, A.J. Surfing p53 Network. Nature 2000, 408, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štraser, A.; Filipič, M.; Žegura, B. Genotoxic effects of the cyanobacterial hepatotoxin cylindrospermopsin in the HepG2 cell line. Arch. Toxicol. 2011, 85, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Shimazaki, Y. Metabolic disorders related to obesity and periodontal disease. Periodontol. 2000 2007, 43, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkis, D.; Bissada, N.F.; Saber, A.; Khaitan, L.; Palomo, L.; Narendran, S.; Al-Zahrani, M.S. Response to Periodontal Therapy in Patients Who Had Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery and Obese Counterparts: A Pilot Study. J. Periodontol. 2011, 83, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, W. How western diet and lifestyle drive the pandemic of obesity and civilization diseases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 2221–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, A.; Lauterbach, M.; Latz, E. Western Diet and the Immune System: An Inflammatory Connection. Immunity 2019, 51, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, K.; Watad, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Lichtbroun, M.; Amital, H.; Shoenfeld, Y. Physical activity and autoimmune diseases: Get moving and manage the disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Physical inactivity and cardiovascular disease at the time of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 906–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K. Anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Role in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 47, 600–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, F.; Helenius-Hietala, J.; Puukka, P.; Färkkilä, M.; Jula, A. Interaction between alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome in predicting severe liver disease in the general population. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2141–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Min, C.; Oh, D.J.; Choi, H.G. Tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption are related to benign parotid tumor: A nested case-control study using a national health screening cohort. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 12, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (Year) | Study Design | Country | Setting | StudyPopulation | Sample Size (N) | Participants Characteristics | Data Collection Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alonso-Pedrero, Lucia et al., 2020 [32] | Prospective Cohort Study (PCS) | Spain | Academical Medical Center (AMC) | Adults | 886 | Age (A)—≈67.7 years Gender (G)—72.8% men | Telomere length (TL) was measured using saliva samples and ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption was collected using a validated 136-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ); the association between consumption of energy-adjusted UPF and the risk of having short telomeres was evaluated using logistic regression models. |

| Baba, Yoshitake et al., 2020 [33] | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Japan | Hospital Care (HC) | Adults | 52 | A—50–69 years G—50% men | For 12 weeks, participants took either (1) three placebo capsules or (2) three catechin capsules per day. At baseline and at 12 weeks after ingestion, blood biomarkers, the Mini-Mental State Examination Japanese version (MMSE-J), and hematologic tests were measured. Body weight (BW), hazard ratios (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), as well as the Cognitrax test battery were measured at baseline, after a single dose, and after 12 w of daily ingestion. |

| Fernández-Real, José Manuel et al., 2012 [34] | RCT | Spain | HC | Elders | 127 | A—55–80 years G—men Disease (D)—Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) or cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk | Participants were randomized to three intervention groups: (1) Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) + virgin olive oil (VOO); (2) MedDiet + nuts; and (3) low-fat diet (control). Dietary intakes were accessed by a 137-item FFQ. Glucose, total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, fasting insulin, total osteocalcin (TOC), undercarboxylated osteocalcin (UOC), and C-telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX) and procollagen I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) levels were measured. |

| Fortin, A. et al., 2018 [35] | Randomized Trial (RT) | Canada | University Hospital (UH) | Adults | 28 | A—18–65 years G—57% men Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 D—Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) ≥ 12-month | For 6 months, participants were randomly assigned, randomized into two intervention groups: (1) MedDiet or (2) low-fat diet. Anthropometric (waist circumference WC), metabolic, and nutritional analyses were performed at inclusion, 3 months, and 6 months. |

| Fretts, Amanda M. et al., 2016 [36] | Cross-sectional study (CSS) | USA | AMC | Adults | 2846 | A—39.6 ± 16.4 years G—60.2% women BMI—32 ± 8 kg/m2 | A 119-item FFQ was used to assess dietary factors, such as past-year consumption of processed meat and unprocessed red meat. Leukocyte telomere length (LTL) was determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Associations of intake of processed meat and unprocessed red meat with LTL were estimated by generalized equations. |

| García-Calzón, Sonia at al., 2015 [37] | RCT | Spain | AMC | Adults | 520 | A—67.0 ± 6.0 years G—55% women BMI > 25 kg/m2 D –T2D or high CVD risk | LTL was measured by quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR and dietary inflammatory index (DII) was calculated using self-reported data collected via the questionnaire. |

| González-Guardia, Lorena et al., 2015 [38] | Cross-over study (COS) | Spain | UH | Elders | 10 | A ≥ 65 years G—50% men | For 4 weeks, participants followed four different isocaloric diets: (1) MedDiet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 (Med + CoQ) diet; (2) MedDiet; (3) Western diet rich in saturated fatty acids (SFAs) diet; (4) Low-fat high-carbohydrate (LFHC) diet enriched in n − 3 polysaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Urine samples were collected for nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at baseline and after a 12-h fast (postintervention). |

| Gu, Yian et al., 2015 [39] | CSS | USA | AMC | Elders | 1743 | A— ≥ 65 years G—68.3% women | The MedDiet was calculated from collected data from FFQ. LTL was retrieved from leukocyte DNA using a RT-PCR to calculate ratio of telomere to single-copy gene sequence (T/S ratio). |

| Guallar-Castillón, Pilar et al., 2012 [40] | CSS | Spain | AMC | Adults | 10,231 | A ≥ 18 years G—51.6% women | A validated computerized diet history was used to assess the diet. Southern European Atlantic Diet (SEAD) adherence was assessed using a nine-food component index. C-reactive protein (CRP), uric acid, TC, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), HDL-C, triglycerides, glucose, glycated hemoglobin, insulin, leptin, and fibrinogen levels were measured in 12 h fasting blood samples, while creatinine and albumin were measured in urine. |

| Gutierrez-Mariscal, Francisco M. et al., 2012 [41] | RCT | Spain | UH | Elders | 20 | A— ≥ 65 years G—50% men BMI—20–40 kg/m2 | Three isocaloric diets were followed for a 4-week each: (1) MedDiet, (2) Med + CoQ diet, and (3) SFA diet. mRNAs levels for p53, p21, p53R2, and mdm2 were determined. |

| Gutierrez-Mariscal, Francisco M. et al., 2014 [42] | RT | Spain | UH | Elders | 20 | A ≥ 65 years G—50% men BMI—20–40 kg/m2 | Three different diets for 4 weeks: (1) Med + CoQ diet, (2) MedDiet, and (3) SFA diet. Metabolic levels, food intake, growth arrest and DNA damage inducible alpha (Gadd45a) and beta (Gadd45b) gene expression and protein levels, and p53 inducible targets for DNA repair were measured. |

| Hernáez, Álvaro et al., 2020 [43] | RCT | Spain | HC | Elders | 358 | A—55–80 years G—63% women D—T2D or CVD risk | Three interventions: (1) MedDiet-VOO (received 1 L/w of virgin olive oil); (2) MedDiet-Nuts (210 g/w of mixed nuts); and (3) low-fat control diet. A 137-item FFQ was used to assess MedDiet adherence at baseline and after one year of intervention. Atherothrombosis biomarkers levels were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). |

| Becerra-Tomás, Nerea et al., 2021 [44] | CSS | Spain | AMC | Elders | 6475 | A—55–75 years G—52.7% men BMI = 27–40 kg/m2 | A 143-item FFQ was used to assess fruit and fruit juice consumption; a 17-item questionnaire was used to evaluate energy-reduced MedDiet adherence; sociodemographic and lifestyle variables were collected. |

| Jalilpiran, Yahya et al., 2020 [45] | CSS | Iran | HC | Elders | 357 | A— ≥ 60 years G—men | A 168-item semiquantitative FFQ was used to evaluate dietary intake. MedDiet and Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) dietary scores were calculated. Anthropometric measures, biochemical parameters, and overall characteristics were also collected. |

| Kanerva, Noora et al., 2014 [46] | Cohort study (CS) | Finland | AMC | Adults | 6490 | A—25–74 years G—53% women | Dietary intake was measured through a 130-item FFQ to calculate Baltic Sea Diet Score (BSDS). Anthropometric measures and leptin, adiponectin, tumor-necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and high-sensitivity (hs)-CRP concentrations were assessed. |

| Khalatbari-Soltani, Saman et al., 2020 [47] | PCS | Switzerland | AMC | Adults | 2288 | A—55.8 ± 10.0 years G—65.4% women | Dietary intake was accessed by a 97-item FFQ to predict the MedDiet score; Fatty liver index (FLI) score was obtained through a logistic function, including BMI, WC, fasting triglycerides, and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels, and Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) liver fat score was calculated based on the presence of metabolic syndrome (MetS), T2D, fasting concentrations of insulin, Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and the AST/ Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio. |

| Kondo, Keiko et al., 2014 [48] | Prospective Non-randomized study (PNRS) | Japan | AMC | Adults | 17 | A—35–60 years G—82.4% men BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | After 2–3 weeks, participants obtained a meal consisting of high fiber and low fat (30 kcal/kg of ideal BW), 3 x/day for 8 weeks, followed by a normal diet for 24 weeks. Insulin, glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), lipids, hs-CRP, tissue plasminogen activator-1 (TPAI-1), fibrinogen, leptin, adiponectin, blood pressure (BP), BW, and WC were measured. |

| Martens, Remy J. H. et al., 2020 [49] | CSS | The Netherlands | AMC | Adults | 2961 | A—59.8 ± 8.2 years G—51% men | Sodium and potassium concentrations were obtained through urine samples, and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI), and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentrations were measured in stored frozen serum samples. |

| Martínez-Lapiscina, Elena H. et al., 2014 [50] | RCT | Spain | HC | Elders | 522 | A—55–80 years (men) and 60–80 (women) D—T2D or CVD risk | Participants were allocated to one of these diets: two MedDiets (supplemented with either (1) extra-virgin olive oil or (2) nuts), or (3) a low-fat diet. After 6.5 years of intervention, they were assessed using the MMSE and the Clock Drawing Test (CDT). The CR1-rs3818361, CLU-rs11136000, PICALM-rs3851179, and Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genes were genotyped in these participants. |

| Mofrad, Manije D. et al., 2019 [51] | CSS | Iran | AMC | Elders | 362 | A—60–80 years G—men | Diet was assessed using a 168-item FFQ. Elderly dietary index (EDI) adherence was calculated based on the modified MyPyramid for older adults. Anthropometric values, biochemical parameters, and BP were measured. The relationships between EDI tertiles and CVD risk factors were investigated using multivariate logistic regression. |

| Mujica-Parodi, Lilianne R. et al., 2020 [52] | CS | USA | AMC | Adults | 42 | A—18–88 years G—52.4% women BMI < 30 kg/m2 | Metabolic neuroimaging datasets; Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition and processing; spatial navigation and motor tasks; functional (fMRI) network analyses. |

| Neth, Bryan J. et al., 2020 [53] | COS | USA | AMC | Adults | 20 | A—50–80 years G—75% women D—MCI risk | Participants consumed either (1) modified Mediterranean-ketogenic diet (MMKD) or (2) American Heart Association Diet (AHAD) (control), for 6 w. Before diet randomization and after each diet, baseline cognitive status, lumbar puncture (LP), MRI, and metabolic profiles were executed. |

| Paoli, Antonio et al., 2011 [54] | PNRS | Italy | AMC | Adults | 106 | A—18–65 years G—82.1% women BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | Participants received a Ketogenic Mediterranean with phytoextracts (KEMEPHY) for 6 w. Weight and TC, triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C, glucose, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), uricemia, VES, creatinine, ALT, AST, GGT levels were measured. |

| Bhanpuri, Nasir H. et al., 2018 [55] | PCS | USA | AMC | Adults | 349 | A—54 ± 8 years G—65.1 ± 3.2% women BMI = 25–30 kg/m2 D—T2D | Continuous care intervention (CCI): health coach and medical provider; Usual care (UC): independently recruited to path T2D progression; circulating biomarkers, BP, carotid intima media thickness (cIMT), multi-factorial risk scores and medication use were examined. |

| Schönknecht, Yannik B. et al., 2020 [56] | RCT | Germany | UH | Elders | 60 | A—60–80 years G—56.7% men BMI—27–34.9 kg/m2 | Participants consumed three different isoenergetic meals: (1) Western diet-like high-fat (WDHF), (2) Western diet-like high-carbohydrate (WDHC), and (3) MedDiet. Blood samples were collected at fasting and between 1 and 5 h postprandially. Lipid and glucose metabolism parameters, inflammation, and oxidation levels, and antioxidant status were examined |

| Song, Xiaoling et al., 2016 [57] | RCT | USA | AMC | Adults | 102 | A—21–79 years G—51% men BMI—19.2–35.5 kg/m2 | Participants were allocated three different diets for 6 w: (1) eucaloric moderate-fat diet, (2) eucaloric low-fat diet, and (3) low-fat diet with a 33% caloric deficit (“low-calorie low-fat diet). Plasma CRP, IL-6, leptin, total adiponectin, and soluble tumour necrosis factor receptors I & II (sTNFRI and -II) concentrations were assayed by ELISA. |

| Tiainen, A-MK. et al., 2012 [58] | CSS | Finland | UH | Adults | 1942 | A—57–70 years | LTL was measured by qPCR. A semiquantitative 12-item FFQ was used to evaluate the diet. |

| Uusitupa, M. et al., 2013 [59] | RCT | Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Sweden | AMC | Adults | 166 | A—30–65 years G—67% women BMI—27–38 kg/m2 | Participants were randomized to two different diets for 18–24 w: (1) control diet or (2) healthy nordic diet. Biochemical and anthropometric measurements were collected. |

| Yousefi, Reyhaneh et al., 2020 [60] | RCT | Iran | AMC | Adults | 40 | A—20–50 years G—82.5% women BMI—25–40 kg/m2 | Participants adhere to restricted-calorie diet (RCD) and received 300 mg/d of (1) grape seed extract (GSE) capsules or (2) placebo capsules for 12 weeks. Anthropometric and biochemical parameters dietary intake were evaluated. |

| Yubero-Serrano, Elena M. et al., 2012 [61] | RCT | Spain | UH | Elders | 20 | A— ≥ 65 years G—50% men BMI—20–40 kg/m2 | Three different diets during the 4 weeks, each: (1) MedDiet, (2) Med + CoQ diet, and (3) SFA diet. p65, Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta (IKK-β), Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, alpha (IkB-α), Matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), interleukin-1β (IL1-β), c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 (JNK-1), x-box–binding protein-1 (sXBP-1), calreticulin (CRT), and glucose-regulated protein 78 kDa (BiP-Grp78) mRNAs levels were analyzed. |

| Boccardi, Virginia et al., 2013 [62] | CS | Italy | AMC | Elders | 217 | A— ≥ 65 years G—53% men BMI—25.86 ± 1.4 kg/m2 | Association among TL, telomerase activity (TA), and MedDiet adherence was studied. Participants were divided according to MedDiet score (MDS) in low adherence (MDS < 3), medium adherence (MDS 4–5) and high adherence (MDS > 6). LTL was measured by qPCR and TA by a PCR-ELISA protocol. |

| Bonaccio, Marialaura et al., 2021 [63] | PCS | Italy | AMC | Adults | 22,475 | A ≥ 35 years G—53.4% women | A 188-item FFQ was used to assess food intake. The NOVA classification defined UPF, and those intakes were categorized as quartiles of the ratio (%) of UPF (g/d) to total food consumed (g/d). |

| Cassidy, Aedín et al., 2010 [64] | PCS | USA | UH | Adults | 2284 | A—30–55 years G—women | LTL was measured by qPCR. A questionnaire was used to examine anthropometric data, diet, and lifestyle. |

| Chou, Yi-Chun et al., 2019 [65] | PCS | Taiwan | UH | Elders | 436 | A— ≥ 65 years G—53% women BMI—23.8 ± 2.9 kg/m2 | The modified Alternative Healthy Eating Index (mAHEI) was used to assess diet quality, which was calculated from a 44-item FFQ at baseline, and vegetable variety was derived from the diet diversity score (DDS). Montreal Cognitive Assessment—Taiwanese version (MoCA-T) (global cognition) and Wechsler Memory Scale-Third edition (WMS-III) (domain cognition) were used to assess global and domain-specific cognition (logical memory and attention domains). |

| Crous-Bou, Marta et al., 2014 [66] | CS | USA | AMC | Adults | 4676 | A—42–70 years G—women | The relationship between relative TL in peripheral blood leukocytes measured by qPCR and the alternate MDS calculated from self-reported dietary data. |

| do Rosario, Vinicius A. et al., 2020 [67] | RCT | Australia | AMC | Adults | 16 | A ≥ 55 years G—81.3 women BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | High fat high energy (HFHE) meal along with 250 mL of: (1) anthocyanins-rich Queen Garnet plum juice (intervention) or (2) apricot juice (control). Blood samples and BP measures were collected at baseline, 2 h, and 4 h following the meal. Vascular and microvascular function were evaluated at baseline and 2 h after the meal. |

| Authors (Year) | Main Results | Biomarkers and Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Alonso-Pedrero, Lucia at al., 2020 [32] | Higher consumption of UPF (>3 servings/d) presented higher risk of having shorter telomeres in an elderly Spanish population. | Participants with >3 servings/day of UPF consumption: higher short telomere risk (p = 0.032), higher family history of CVD (p = 0.045), and diabetes and dyslipidemia prevalence (p = 0.014); higher consumption of fats, SFAs, sodium, sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), fast food, and processed meat (p < 0.001), PUFAs (p = 0.011), dietary cholesterol (p = 0.008); less adherence to the MedDiet (p < 0.001). |

| Baba, Yoshitake et al., 2020 [33] | Intake of 336.4 mg of Green Tea Catechins (GTC) promoted working memory in adults. | GTC: significantly lower commission errors on the CPT (p = 0.004), after a single dose; significantly lower correct response time on the 4-part CPT (FPCPT) (p = 0.012). |

| Fernández-Real, José Manuel et al., 2012 [34] | Consumption of MedDiet + VOO for 2 years increased (serum osteocalcin) and (P1NP), indicating bone-protective effects. | MedDiet + VOO: TOC concentrations increased (p = 0.007), P1NP levels increased (p < 0.01); consumption of olives: positively associated with both baseline total osteocalcin (p = 0.02) and 2 year (osteocalcin) (p = 0.04). |

| Fortin, A. et al., 2018 [35] | MedDiet and low-fat diet in patients with T1D and MetS could help with weight loss, with no significant changes in anthropometric and metabolic parameters between regimens. | BMI, WC, weight, and triglycerides: decreased overtime with both diets (p < 0.05). |

| Fretts, Amanda M. et al., 2016 [36] | Processed meat, but not unprocessed red meat consumption, was linked to a shorter LTL. | Processed meat: inverse correlation with LTL (p = 0.009), after adjustment for potential mediators, including SBP, LDL-C, fibrinogen, and BMI. |

| García-Calzón, Sonia at al., 2015 [37] | Diet, through proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory pathways, could be a fundamental predictor of telomere length. | DII score 3: inverse significant association with TL (p = 0.001) |

| González-Guardia, Lorena et al., 2015 [38] | MedDiet + CoQ promotes urine metabolites excretion, reducing oxidative stress. Metabolites excreted after SFA diet are linked to increased oxidative stress. | MedDiet + CoQ: higher hippurate urine levels and reduced phenylacetylglycine levels (p < 0.05); inversely related to Nrf2 and thioredoxin (Trx) (p = 0.004), superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1) (p = 0.03) and gp91phox subunit of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase gene expression (p = 0.039); SFA diet: phenylacetylglycine excretion was negatively related to CoQ (p = 0.039) and positively correlated with isoprostane urinary levels (p = 0.013). |

| Gu, Yian et al., 2015 [39] | Among whites, greater adherence to a MedDiet was significantly connected with longer LTL. In addition, eating a diet rich in vegetables and poor in meat, dairy, or cereal might contribute to longer LTL. | MedDiet adherence: higher LTL in whites (p-trend = 0.02); consumption of vegetables and cereals: increased LTL (p = 0.002 and p = 0.003); consumption of reduced dairy and meat intake: increased LTL (p = 0.05 and p = 0.004). |

| Guallar-Castillón, Pilar et al., 2012 [40] | SEAD may prevent myocardial infarction by lowering inflammation markers and reducing triglycerides, insulin, insulin resistance, and SBP. | Higher SEAD adherence: lower plasma CRP, insulin, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), urine albumin, and SBP (p-trend < 0.001), triglycerides (p-trend = 0.012), urine albumin/creatinine ratio (p-trend < 0.034). |

| Gutierrez-Mariscal, Francisco M. et al., 2012 [41] | MedDiet protects DNA from oxidative damage and CoQ supplementation enhances this protection, lowering p53 activation. On the other hand, SFA diet potentiate oxidative stress and p53 stabilization. | Med + CoQ diet: increase of fasting plasma (CoQ) and postprandial (2 h) plasma [CoQ] (p < 0.001 and p = 0.018); decrease of plasma (8-OHdG) (p < 0.0001) and after postprandial period (p = 0.026), of p53 postprandial levels (p < 0.05), of nuclear p-p53 (Ser20) postprandial levels (p = 0.0013), of NM-p53 postprandial (p < 0.05) and of CM-p53 postprandial levels (p = 0.046); MedDiet: decrease of CM-p53 postprandial levels (p = 0.043) and increase of mdm2 mRNA levels (p < 0.05); SFA diet: higher fasting plasma concentrations of TC (p < 0.001), LDL-C (p = 0.013), ApoB (p = 0.017), Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) (p = 0.002) and p53 mRNA levels (p = 0.047); |

| Gutierrez-Mariscal, Francisco M. et al., 2014 [42] | In comparison to the harmful activity of an SFA diet, which initiates the p53-dependent DNA repair mechanism, the MedDiet diet and MedDiet + CoQ10 have beneficial effects on DNA damage. | Med + CoQ: lower mRNA Gadd45a, mRNA Gadd45b, mRNA Ogg1, nuclear APE-1/Ref-1 protein level, mRNA DNA polβ, and mRNA XPC (p = 0.044, p = 0.027, p = 0.048, p = 0.038, p = 0.041 and p = 0.019, respectively). |

| Hernáez, Álvaro et al., 2020 [43] | The MedDiet improved atherothrombosis biomarkers (HDL, fibrinogen, and Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) levels) in high cardiovascular risk individuals. | Adherence to MedDiet: increased activity of platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH) in HDLs (adjusted difference: +7.5% (0.17; 14.8) and HDL-bound 𝛼1-antitrypsin levels (adjusted difference: −6.1% [−11.8; −0.29]; reduced fibrinogen (adjusted difference: −9.5% (−18.3; −0.60) and NEFA concentrations (adjusted difference: −16.7% (−31.7; −1.74)). |

| Becerra-Tomás, Nerea et al., 2021 [44] | In older adults with MetS, increased total fruit consumption is linked with lower WC, plasma glucose and LDL-C levels, as well as higher SBP and DBP. Total and natural fruit juice consumption was associated with reduced WC and glucose levels. | Higher total fruit consumption: significantly reduction in WC and glucose (p = 0.01) and LDL-C (p < 0.01); significantly increase DBP (p < 0.01); higher total fruit juice consumption: significantly reduces WC and glucose (p < 0.01); higher consumption of orange fruits (increase in SBP and DBP (p < 0.01)); green fruits (decrease in glucose (p = 0.01) and increase in HDL-C (p = 0.01)); red/purple fruits (decrease in glucose (p = 0.01)); white fruits (decrease in BMI and WC (p < 0.01)). |

| Jalilpiran, Yahya et al., 2020 [45] | Inverse correlation between the DASH and MedDiet patterns and several cardiovascular risk factors. | Greater adherence to MedDiet: lower WC, triacylglycerol, hs-CRP, fibrinogen, and higher HDL-C (p < 0.05); lower DBP (p = 0.01) and fibrinogen levels (p < 0.001); Greater adherence to DASH: lower fibrinogen (p < 0.05); reduced risk of high DBP (p < 0.001), insulin levels (p = 0.001), hs-CRP (p = 0.009), and fibrinogen (p < 0.001). |

| Kanerva, Noora et al., 2014 [46] | Lower hs-CRP levels are due to the Baltic Sea diet. | BSDS: inverse association with hs-CRP (p < 0.01), contributed mainly by high intake of Nordic fruits and cereals, low intake of red and processed meat, and moderate intake of alcohol (p < 0.05). |

| Khalatbari-Soltani, Saman et al., 2020 [47] | Adherence to the MedDiet decreased hepatic steatosis risk based on the FLI, in addition to the existing evidence of reducing CVD risk. When different parameters for determining the NAFLD score were used, no connection was found. | Adherence to MedDiet: lower risk of hepatic steatosis based on FLI (p-trend < 0.006), after adjustment for BMI (p-trend = 0.031) and after adjustment of BMI and WC (p-trend = 0.034). |

| Kondo, Keiko et al., 2014 [48] | Treatment with a high-fiber, low-fat diet for 8 weeks effectively improved periodontal disease markers and metabolic profiles, at least in part, by mechanisms effects other than caloric restriction. | High-fiber, low-fat diet: significantly reduced probe depth (PD), Clinical attachment loss (CAL), bleeding on probing (BOP), and Gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) (p < 0.005), and showed improvement of BW, HbA1c (p < 0.0001), and hs-CRP (p = 0.038). |

| Martens, Remy J. H. et al., 2020 [49] | 24 h urinary sodium excretion (UNaE) was not connected with the examined cardiac biomarkers; lower 24 h urinary potassium excretion (UKE) was nonlinearly linked with higher hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP. | Diets rich in Potassium: lower hs-cTnT (p = 0.023) and NT-proBNP (p = 0.005). |

| Martínez-Lapiscina, Elena H. et al., 2014 [50] | The preventive impact of MedDiet may be larger for patients with a favorable genetic profile because it regulates the effect of genetic risk factors on cognition. | MedDiet: beneficial effect in CLU gene rs11136000 variant carrying the T minor allele in MMSE test (p < 0.001) and CDT score (p = 0.001), in CR1 gene rs3818361 variant without the A minor risk allele in MMSE test (p = 0.001) and CDT score (p = 0.006); in PICALM rs3851179 polymorphism with at least one T minor allele in CDT score (p = 0.005); and in non-APOE4 carriers in MMSE test (p = 0.007) and CDT (p < 0.001) |

| Mofrad, Manije D. et al., 2019 [51] | Higher EDI was associated with lower risk of being overweight or obese, as well as having LDL-C levels. However, in elderly men, there was no significant association between EDI and other CVD risk factors. | Highest tertile of EDI: higher consumption of fruits, vegetables, fish, olive oil, bread, cereal, and dairy products (p < 0.05); EDI: associated with higher intakes of carbohydrates, SFA, PUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), cholesterol, folate vitamin B1, vitamin B6, vitamin A, vitamin C, potassium, and magnesium (p < 0.05); Higher EDI: lower weight, BMI, WC, serum insulin, HOMA-IR, fibrinogen, ALT, AST, and DBP (p < 0.05); higher fasting blood sugar (FBS), HDL-C, TC levels, and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) (p < 0.05). |

| Mujica-Parodi, Lilianne R. et al., 2020 [52] | Destabilization of brain networks may be an early sign of hypometabolism, which is linked to dementia. Dietary interventions that result in ketone utilization increase available energy and, as a result, may have the potential to protect the aging brain. | KD: decreased destabilization of brain network (DBN) (p < 0.001); higher amplitude for low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) (p < 0.001); cognitive acuity: declined with age (p < 0.001); network switching: inverse association with ALFF (p < 0.001). |

| Neth, Bryan J. et al., 2020 [53] | MMKD may help prevent cognitive decline in adults at risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk, by improving cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarker profile, peripheral lipid and glucose metabolism, cerebral perfusion and cerebral ketone body uptake. | MMKD: higher fasting ketone body levels (p = 0.008), mainly in subjective memory complaints (SMC) group (p = 0.015); reduced very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C) levels and triglycerides (p = 0.02); increased CSF Aβ42 (p = 0.04) and decreased tau levels in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) group (p = 0.007); increased cerebral perfusion, mainly in MCI group (p < 0.05) and cerebral ketone body uptake (11C-acetoacetate (p = 0.02); AHAD: decreased tau levels in MCI group (p = 0.02). |

| Paoli, Antonio et al., 2011 [54] | The KEMEPHY diet resulted in weight and WC loss, as well as improvements in cardiovascular risk markers. | KEMEPHY diet: reduction in BMI, BW, % fat mass, WC, TC, LDL-C, triglycerides, and blood glucose (p < 0.0001); increase in HDL-C (p < 0.0001). |

| Bhanpuri, Nasir H. et al., 2018 [55] | After a year, CCI improved the majority of biomarkers of CVD risk in T2D patients. The increase in LDL-C seems to be restricted to the large LDL subfraction. LDL particle size increased, while total LDL-P and ApoB remain unchanged, and inflammation and BP decreased. | Decrease in weight, ApoB/ApoA1 ratio, triglycerides, triglycerides/HDL-C ratio, large very low-density lipoprotein particle (VLDL-P), small LDL-P, BP, hs-CRP, white blood count (WBC), 10-year Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score, antihypertensive medication (AHM) use (p < 0.001); increase in ApoA1, LDL-C, HDL-C, LDL-P size, and large HDL-P (p < 0.001). |

| Schönknecht, Yannik B. et al., 2020 [56] | A high-energy meal caused hyperglycemia, hyperlipemia, and a decrease in antioxidant markers, whereas the MedDiet had a positive effect on glycemic, insulinemic, and lipemic responses. | WDHC: increased glucose (p = 0.002) and insulin levels (p < 0.001), compared with other meals WDHF: increased triglycerides levels and higher NEFA (p < 0.001), compared with other meals MedDiet: higher vitamin C levels (p < 0.001), compared with other meals. |

| Song, Xiaoling et al., 2016 [57] | Moderate weight loss had little effect on systemic inflammation in relatively healthy adults. A lower dietary fat and higher carbohydrate content had little impact on systemic inflammation measures but significantly reduced adiponectin concentrations when compared to a moderate-fat diet. | Low-calorie, low-fat,(LCLF) diet: greater reductions in weight, fat mass and fasting leptin levels (p < 0.001), compared to other diets; reduced adiponectin (p = 0.008), compared to low-fat diets; adiponectin: tend to increase with weight loss (p = 0.051). |

| Tiainen, A-MK. et al., 2012 [58] | Fat intake is inversely associated with LTL whereas vegetable intakes were positively associated with LTL. | Vegetable intake: positive association with LTL (p = 0.05) in women, after adjustments. Total fat, SFAs, and butter intake: inverse correlation with LTL (p = 0.04, p = 0.01 and p = 0.04). |

| Uusitupa, M. et al., 2013 [59] | Healthy Nordic diet improved lipid profile and reduced low-grade inflammation. | Healthy Nordic diet: lower non-HDL-C (p = 0.04), LDL-C/HDL-C ratio (p = 0.046), ApoB/ApoA1 ratio (p = 0.025); control diet: increased interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 Ra) (p = 0.00053), related with saturated fats and magnesium+ intake (p = 0.049 and p = 0.012). |

| Yousefi, Reyhaneh et al., 2020 [60] | When combined with a calorie-restricted diet, daily consumption of 300 mg GSE improved LDL-C, HDL-C, visceral adiposity index (VAI), and atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) and helps to ameliorate some CVD risk factors in obese or overweight individuals. | GSE: significantly increase in HDL-C and HDL-C/LDL-C at w 12 (p = 0.01 and 0.003, respectively) and significantly decrease in LDL-C (p = 0.04), compared to placebo; significantly decreased VAI, AIP, TC and triglycerides compared to baseline (p =0.04, p = 0.02, p =0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively). |

| Yubero-Serrano, Elena M. et al., 2012 [61] | The anti-inflammatory effect of a MedDiet rich in olive oil and exogenous CoQ supplementation has an additive effect in aged men and women, regulating the inflammatory response and ER stress, indicating that a MedDiet + CoQ is helpful for healthy aging. | Med + CoQ: higher fasting plasma (CoQ) (p < 0.001) and plasma CoQ levels compared with the Med and SFA diets (p = 0.018 and p = 0.032), increase in IkB-α mRNA levels compared with the SFA diet (p = 0.028), decrease in IKK-β, p65 and IL-1β mRNA levels compared with the other diets (p = 0.010; p = 0.008 and p = 0.012; p = 0.011). MedDiet: lower p65, IKK-β, MMP-9 and IL-1β mRNA levels compared with the SFA diet (p = 0.033, p = 0.034; p = 0.034; p = 0.029), higher levels of IkB-α mRNA (p = 0.018). SFA diet: higher MMP-9 (p = 0.008 and p = 0.032), IL-1b (p = 0.017), JNK-1 (p = 0.037), sXBP-1 (p = 0.033 and p = 0.008), CRT (p = 0.031) and BiP/Grp78 (p = 0.021) mRNA levels compared with Med and Med + CoQ diets. |

| Boccardi, Virginia et al., 2013 [62] | Lower telomere shortening and higher Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) TA may play a role in lifespan and, more importantly, health span in populations consuming traditional MedDiet. | LTL: shorter with age (p < 0.001) and positive correlation with TA (p = 0.028), higher in women (p < 0.001) and differ according to smoking status (p < 0.001); negatively correlated with IS (p < 0.001) and nitrotyrosine (p = 0.011). PBMC TA: negatively correlated with both inflammation score (IS) (p = 0.048) and nitrotyrosine levels (p = 0.022); MDS ≥ 6: longer TL (p = 0.003) and higher TA (p = 0.013); lower plasmatic levels of CRP (p = 0.018), IL-6 (p = 0.010), TNF-α (p = 0.021) and nitrotyrosine (p = 0.009); IS: positively correlated with nitrotyrosine levels (p < 0.001). |

| Bonaccio, Marialaura et al., 2021 [63] | Higher levels of UPF were linked to increased risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, partly due to its high dietary content of sugar. | Intake of UPF: lower adherence to the MedDiet and intake of fiber (p < 0.001); higher energy intake, fat, sugar, dietary cholesterol, and Na+ (p < 0.001); increased risks of CVD mortality (HR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.23, 2.03), death from ischemic heart disease (IHD)/cerebrovascular disease (HR: 1.52; 95% CI: 1.10, 2.09), and all-cause mortality (HR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.46). |

| Cassidy, Aedín et al., 2010 [64] | LTL, which is a putative biomarker of chronic disease risk, is associated with body composition and dietary factors. | Fiber intake (cereal fiber and whole grains) and vitamin D: higher LTL (p = 0.006, p = 0.01 and p = 0.01); LTL: inversely correlated with age (p < 0.0001), BMI (p = 0.005), WC (p = 0.009), weight (p = 0.004) and linoleic acid (p = 0.0009) and total fat intake (p = 0.003), including MUFAs and PUFAs (p = 0.006 and p = 0.0008). |

| Chou, Yi-Chun et al., 2019 [65] | In older adults, a high-quality diet containing a variety of vegetables was linked to a lower incidence of cognitive decline. | High diet quality with high vegetable diversity: lower risk of global cognitive decline (p-trend = 0.03) and of decline of attention domain (p-trend = 0.049); lower risk of global cognitive decline (p-trend = 0.03) in elders. |

| Crous-Bou, Marta et al., 2014 [66] | Longer telomeres were associated with greater adherence to the MedDiet. These results further support the benefits of adhering to this diet in terms of promoting health and longevity. | MedDiet score: proportional with TL (p = 0.016); higher in women with lower BMI (p = 0.01), who smoked less, had higher intake of total energy, were more physically active; higher with vegetables, fruits, grains, fish, nuts, and total fat intake, as well as lower meat intake (p < 0.001); TL: longer in younger women (p < 0.001); shorter in women who smoked more (p = 0.02); LTL: longer with AHEI (p = 0.02). |

| do Rosario, Vinicius A. et al., 2020 [67] | In overweight older individuals, fruit-based anthocyanins attenuated the potential negative postprandial effects of a HFHE challenge on vascular and microvascular function, as well as inflammation biomarkers. | Anthocyanin: higher postprandial flow mediated dilation (FMD) and post-occlusive reactive hyperaemia maximum perfusion (PORHmax) (p < 0.05), after 2 h; lower CRP (p < 0.05) and trend to lower IL-6 (p = 0.075), after 4 h. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leitão, C.; Mignano, A.; Estrela, M.; Fardilha, M.; Figueiras, A.; Roque, F.; Herdeiro, M.T. The Effect of Nutrition on Aging—A Systematic Review Focusing on Aging-Related Biomarkers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030554

Leitão C, Mignano A, Estrela M, Fardilha M, Figueiras A, Roque F, Herdeiro MT. The Effect of Nutrition on Aging—A Systematic Review Focusing on Aging-Related Biomarkers. Nutrients. 2022; 14(3):554. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030554

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeitão, Catarina, Anna Mignano, Marta Estrela, Margarida Fardilha, Adolfo Figueiras, Fátima Roque, and Maria Teresa Herdeiro. 2022. "The Effect of Nutrition on Aging—A Systematic Review Focusing on Aging-Related Biomarkers" Nutrients 14, no. 3: 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030554

APA StyleLeitão, C., Mignano, A., Estrela, M., Fardilha, M., Figueiras, A., Roque, F., & Herdeiro, M. T. (2022). The Effect of Nutrition on Aging—A Systematic Review Focusing on Aging-Related Biomarkers. Nutrients, 14(3), 554. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030554