Understanding the Risks and Benefits of a Patient Portal Configured for HIV Care: Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

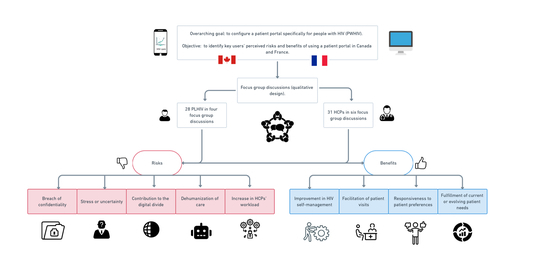

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Context and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Potential Risks of Using a Patient Portal

3.2. Potential Benefits of a Patient Portal for HIV Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, S.C. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection: When to Initiate Therapy, Which Regimen to Use, and How to Monitor Patients on Therapy. Top Antivir Med. 2016, 23, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hasina, S.; Angela, C.; Robert, S.H.; Sharada, P.M.; Keri, N.A.; Kate, B.; Burchell, A.N.; Cohen, M.; Gebo, K.A.; Gill, M.J.; et al. Closing the gap: Increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81355. [Google Scholar]

- Kumi Smith, M.; Jewell, B.L.; Hallett, T.B.; Cohen, M.S. Treatment of HIV for the Prevention of Transmission in Discordant Couples and at the Population Level. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1075, 125–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.M.; Eisinger, R.W.; Fauci, A.S. Comorbidities in Persons With HIV The Lingering Challenge. JAMA 2020, 323, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remien, R.H.; Stirratt, M.J.; Nguyen, N.; Robbins, R.N.; Pala, A.N.; Mellins, C.A. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: The need for an integrated response. AIDS 2019, 33, 1411–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koester, K.A.; Johnson, M.O.; Wood, T.; Fredericksen, R.; Neilands, T.B.; Sauceda, J.; Crane, H.M.; Mugavero, M.J.; Christopoulos, K.A. The influence of the ‘good’ patient ideal on engagement in HIV care. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Manafo, E.; Petermann, L.; Mason-Lai, P.; Vandall-Walker, V. Patient engagement in Canada: A scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, T.; Larson, E.; Schnall, R. Unraveling the meaning of patient engagement: A concept analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondenge, K.; Renju, J.; Bonnington, O.; Moshabela, M.; Wamoyi, J.; Nyamukapa, C.; Seeley, J.; Wringe, A.; Skovdal, M. I am treated well if I adhere to my HIV medication: Putting patient-provider interactions in context through insights from qualitative research in five sub-Saharan African countries. Sex Transm. Infect. 2017, 93 (Suppl. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marshall, R.; Beach, M.C.; Saha, S.; Mori, T.; Loveless, M.O.; Hibbard, J.H.; Cohn, J.A.; Sharp, V.L.; Korthuis, P.T. Patient activation and improved outcomes in HIV-infected patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Patient Engagement. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 2019. Available online: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/45851.html (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Flickinger, T.E.; Saha, S.; Moore, R.D.; Beach, M.C. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J. Acquir. Immun. Defic. Syndr. 2013, 63, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kruse, C.S.; Bolton, K.; Freriks, G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kruse, C.S.; Argueta, D.A.; Lopez, L.; Nair, A. Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammenwerth, E.; Schnell-Inderst, P.; Hoerbst, A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: A systematic review of controlled trials. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte-Trojel, T.; de Bont, A.; Aspria, M.; Adams, S.; Rundall, T.G.; van de Klundert, J.; de Mul, M. Developing patient portals in a fragmented healthcare system. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2015, 84, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irizarry, T.; DeVito Dabbs, A.; Curran, C.R. Patient Portals and Patient Engagement: A State of the Science Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Technology OotUNCfHI. What Is a Patient Portal? 2016. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-patient-portal (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- Services USDoHaH; Administration FaD; (CDER) CfDEaR; (CBER) CfBEaR; (CDRH) CfDaRH. Guidance for Industry. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims; US Food & Drug Administration (FDA): Silver Spring, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Weinhardt, L.; Benotsch, E.; DiFonzo, K.; Luke, W.; Austin, J. Internet access and Internet use for health information among people living with HIV-AIDS. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 46, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, A.L.; Groessl, E.J. Chronic disease self-management and adherence to HIV medications. J. Acquir. Immun. Defic. Syndr. 2002, 31 (Suppl. 3), S163–S166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.C.; Ash, J.S.; Bates, D.W.; Overhage, J.M.; Sands, D.Z. Personal health records: Definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2006, 13, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kahn, J.S.; Hilton, J.F.; Van Nunnery, T.; Leasure, S.; Bryant, K.M.; Hare, C.B.; Thom, D.H. Personal health records in a public hospital: Experience at the HIV/AIDS clinic at San Francisco General Hospital. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2010, 17, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ralston, J.D.; Silverberg, M.J.; Grothaus, L.; Leyden, W.A.; Ross, T.; Stewart, C.; Carzasty, S.; Horberg, M.; Catz, S.L. Use of web-based shared medical records among patients with HIV. Am. J. Manag. Care 2013, 19, e114–e124. [Google Scholar]

- Oster, N.V.; Jackson, S.L.; Dhanireddy, S.; Mejilla, R.; Ralston, J.D.; Leveille, S.; Delbanco, T.; Walker, J.D.; Bell, S.K.; Elmore, J.G. Patient Access to Online Visit Notes: Perceptions of Doctors and Patients at an Urban HIV/AIDS Clinic. J. Int. Assoc. Provid AIDS Care 2015, 14, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fingleton, N.A.; Watson, M.C.; Matheson, C. You are still a human being, you still have needs, you still have wants: A qualitative exploration of patients’ experiences and views of HIV support. J. Public Health 2018, 40, e571–e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, V.; Clatworthy, J.; Youssef, E.; Llewellyn, C.; Miners, A.; Lagarde, M.; Sachikonye, M.; Perry, N.; Pollard, A.; Sabin, C.; et al. Which aspects of health care are most valued by people living with HIV in high-income countries? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Engler, K.V.S.; Ma, Y.; Hijal, T.; Cox, J.; Ahmed, S.; Klein, M.; Achiche, S.; Pai, N.P.; de Pokomandy, A.; Lacombe, K.; et al. Implementation of an electronic patient-reported measure of barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence with the Opal patient portal: A mixed method type 3 hybrid pilot study at a large Montreal HIV clinic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kildea, J.; Battista, J.; Cabral, B.; Hendren, L.; Herrera, D.; Hijal, T.; Joseph, A. Design and Development of a Person-Centered Patient Portal Using Participatory Stakeholder Co-Design. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The I-Score Study: Developing a New Patient-Reported Tool for the Routine HIV Care of Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2019. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02586584 (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Française, R. Décret n° 2017-884 du 9 Mai 2017 Modifiant Certaines Dispositions Réglementaires Relatives aux Recherches Impliquant la Personne Humaine Paris: LegiFrance. 2017. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/decret/2017/5/9/2017-884/jo/texte (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmeijer, R.E.; McNaughton, N.; Van Mook, W.N. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med. Teach. 2014, 36, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.N.E.; McKenna, K. How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods 2016, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, S. Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Res. 1997, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L. Using NVivo in Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 1999; ISBN 0-7619-6525-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Turunen, H.; Bondas, T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013, 15, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, L.M. 100 Questions (and Answers) About Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.M.; Osterhage, K.; Hartzler, A.; Joe, J.; Lin, L.; Kanagat, N.; Demiris, G. Use of Patient Portals for Personal Health Information Management: The Older Adult Perspective. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2015, 2015, 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zettel-Watson, L.; Tsukerman, D. Adoption of online health management tools among healthy older adults: An exploratory study. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerai, P.; Wood, P.; Martin, M. A pilot study on the views of elderly regional Australians of personally controlled electronic health records. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Schuster, T.; Lessard, D.; Mate, K.; Engler, K.; Ma, Y.; Abulkhir, A.; Arora, A.; Long, S.; de Pokomandy, A.; et al. Acceptability of a Patient Portal (Opal) in HIV Clinical Care: A Feasibility Study. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandachi, D.; Dang, B.N.; Lucari, B.; Teti, M.; Giordano, T.P. Exploring the Attitude of Patients with HIV About Using Telehealth for HIV Care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.; Gonzalez, R.; Priolo, C.; Schapira, M.M.; Sonnad, S.S.; Hanson, C.W., 3rd; Langlotz, C.P.; Howell, J.T.; Apter, A.J. True “meaningful use”: Technology meets both patient and provider needs. Am. J. Manag. Care 2015, 21, e329–e337. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, D.; Aslan, A.; Zeggagh, J.; Morel, S.; Michels, D.; Lebouche, B. Acceptability of a digital patient notification and linkage-to-care tool for French PrEPers (WeFLASH((c))): Key stakeholders’ perspectives. Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 1397–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Vuturo, A.E.M.L.; Osyborn, C.Y. Patients reported this expanded access as contributing to more efficient and higher-quality face-to-face visits because patients could keep their provider informed of changes that occurred between visits. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Lusignan, S.; Ross, P.; Shifrin, M.; Hercigonja-Szekeres, M.; Seroussi, B. A comparison of approaches to providing patients access to summary care records across old and new europe: An exploration of facilitators and barriers to implementation. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2013, 192, 397–401. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, D.E.; Rocha, R.A.; Tse, T. Enhancing access to patient education information: A pilot usability study. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2005, 892. [Google Scholar]

- Bristowe, K.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Clift, P.; James, R.; Josh, J.; Platt, M.; Whetham, J.; Nixon, E.; Post, F.A.; McQuillan, K.; et al. The development and cognitive testing of the positive outcomes HIV PROM: A brief novel patient-reported outcome measure for adults living with HIV. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.N.; Hanson, K.A.; Harding, G.; Haider, S.; Tawadrous, M.; Khachatryan, A.; Khachatryan, A.; Pashos, C.L.; Wu, A.W. Patient reported outcome instruments used in clinical trials of HIV-infected adults on NNRTI-based therapy: A 10-year review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kjaer, A.; Rasmussen, T.A.; Hjollund, N.H.; Rodkjaer, L.O.; Storgaard, M. Patient-reported outcomes in daily clinical practise in HIV outpatient care. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Powell, K.R. Patient-Perceived Facilitators of and Barriers to Electronic Portal Use: A Systematic Review. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2017, 35, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.U.S.K.; Meyers, J.; Haverhals, L.M.; Cali, S.; Ross, S.E. Designing a personal health application for older adults to manage medications. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Health Informatics Symposium, Arlington, VA, USA, 11–12 November 2010; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 849–859. [Google Scholar]

- Montelius, E.; Astrand, B.; Hovstadius, B.; Petersson, G. Individuals appreciate having their medication record on the web: A survey of attitudes to a national pharmacy register. J. Med. Internet Res. 2008, 10, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| Account settings | Account settings allow patients to customize the portal to their preferences, including language and font size. |

| Calendar | A calendar function allows patients to view their upcoming appointments. |

| Check-in | Patients can notify HCPs of their arrival at the clinic and receive approximate waiting times. |

| Consultation notes | HCP’s (clinicians and nurses) consultation notes are displayed for the patient to view. |

| Diagnostic test results | Patients may access their laboratory test results, including a longitudinal display of trends. |

| Education material | Personalized education material with explanatory content is provided in text and/or video formats. |

| Navigation tool | An intra-hospital map orients patients to their clinic or room. |

| Notifications | Notifications advise patients when it is time for their appointment and if patients are next in line for treatment or their appointment. |

| PROMs | Self-reported electronic questionnaires are administered to patients to identify pertinent symptoms, concerns, or needs. |

| Texting | Direct text messaging allows HCPs to send announcements and messages to their patients. |

| Treatment Planning | Patients can view their personal treatment plan and planning status information. |

| People Living with HIV (n = 28) % | Healthcare Providers (n = 31) % | |

|---|---|---|

| Focus group | ||

| MUHC (English) | 7 (25) | |

| MUHC (French) | 5 (18) | |

| MUHC (French) | 8 (29) | |

| Saint-Antoine Hospital (French) | 8 (29) | |

| MUHC (English) | 6 (19) | |

| MUHC (French) | 6 (19) | |

| MUHC (French) | 4 (13) | |

| Saint-Antoine Hospital (French) | 7 (23) | |

| Non-MUHC Montreal (French) | 8 * (26) | |

| Age group | ||

| 20–39 | 6 (21) | 8 (26) |

| 40–59 | 15 (54) | 14 (45) |

| 60–79 | 5 (18) | 3 (10) |

| Missing | 2 (7) | 6 (19) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 18 (64) | 10 (32) |

| Female | 9 (32) | 20 (64) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 15 (54) | N/A |

| Men who have sex with men | 10 (36) | |

| Bisexual | 2 (7) | |

| Other | 1 (4) | |

| Preferred language | ||

| French | 17 (61) | 18 (58) |

| English | 6 (21) | 7 (23) |

| French and English | 4 (14) | 6 (19) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Occupation | ||

| Physician | N/A | 13 (42) |

| Pharmacist | 8 (26) | |

| Nurse | 6 (19) | |

| Social Worker | 2 (6) | |

| Clinical care coordinator | 2 (6) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African | 13 (46) | N/A |

| Caucasian | 11 (39) | |

| Latino | 4 (14) |

| Potential of Patient Portal Use | Participant Quotations | |

|---|---|---|

| People Living with HIV | Healthcare Providers | |

| Risks | ||

| Breach of confidentiality | You should talk with your doctor, because maybe you don’t understand if you share this note (to other HCPs). So, I think it’s extremely sensitive and it should be controlled, or you should be conscious about what you are sharing. (European Man, 28 years old, heterosexual) Log in on your (patient portal) and you will be able to see whatever. For example, imagine if you lose your phone and someone has access. (African male, 44 years old, heterosexual) From (your) lab results everyone can know that you are under HIV treatment … that your viral load is that, your CD4 is that. (White male, 61 years old, heterosexual) | You can’t have an application that stays open, let’s say someone has their phone and someone else comes across and just looks at the phone and see that it’s open. (Pharmacist) There has to be some programming where if you haven’t used it in 30 s you are logged out. (Pharmacist) There are much more concerns surrounding privacy and confidentiality and the high rate of psychiatric illness in our population and drug use…There are issues about having that (consultation notes) accessible to others…(Physician) |

| Stress or uncertainty | (If) I cannot interpret the results in the right way… I start stressing for the next two weeks before I see my doctor. (African male, 40 years old, Heterosexual) If there is a snowstorm and the internet is interrupted, I don’t know how fast the changes of the dates or appointments would be. (African woman, 30 years old, heterosexual) | I would like to have… a portal where the person has reliable (health) information. (as misinformation can cause stress) (Physician) Somebody might have a viral load of 24 and it can cause huge anxiety. (Nurse) |

| Contribution to the digital divide | Yes, but they will still need to have a somewhat sophisticated phone if they want to have the application. (White man, 70 years old, Men who have sex with men) I don’t want to have it as an app on my phone, but I want to have it at home on my computer. (Since not all PLWH have smartphones) (African man, 44 years old, heterosexual) There are some phones that are not compatible with it (a patient portal’s features) (African man, 40 years old, heterosexual) | How many refugees have a phone? (Nurse) (A patient portal) is based on the fact that you have to have a phone. (Social worker) It will only be those who have access to a smartphone that can use it. (Nurse) |

| Dehumanization of care | I would have liked the doctor to reassure me, to meet me at least to tell me (about their laboratory results) (African woman, 58 years old, heterosexual) You cannot call somebody to counsel you on the phone. You need to see the person physically and emotionally so I’m wondering how it can be put into (a patient portal). (African man, 51 years old, heterosexual) | I don’t think there is any other replacement other than a person (Physician) It’s warmer when someone who knows you greets you, than a machine. (Physician) |

| Increase in healthcare provider workload | If you are talking to her (the clinician) about something and then it becomes long, it will be like 15 min with you for her she’s not getting paid or he is not getting paid (if using a patient portal to communicate). (African woman, 30 years old, heterosexual) | In addition to having an application where I would have to respond to concerns in real time, I definitely don’t want that, because it will make our lives unmanageable. (Physician) It will need a lot of support because we are not accessible 24 h a day. (Physician) |

| Benefits | ||

| Improvement in HIV self-management | The (calendar) is really good… because we know that one or two weeks before you see the doctor you need blood tests. (African man, 40 years old, heterosexual) Yes (on sharing consultation notes) if you are not dealing with the people here… If it (the clinic visit) happens in Toronto, you need to go to the hospital and the doctor will be asking a lot of questions. (White male, 61 years old, heterosexual) I would need in a patient portal probably just general information like what’s new with research, what new discoveries have been made recently. (Latino man, 46 years old, bisexual) | If this (notification function) can be integrated into the patient’s application, it will greatly simplify medication renewal. (Pharmacist) I think it’s (a patient portal) useful. People are unfortunately not always informed, or at least not always aware of their problems, or they minimize them (for access to consultation notes and PROMs). (Physician) I think it’s great for patients to know and they can show it (consultation notes) to whoever in their family. (Social worker) It would be good if the patients had a list of all the community organizations, their roles, and their contact information, and where to go if you are a woman with HIV. (Pharmacist) |

| Facilitation of patient visits | I have so many things to tell her at one time. Of course, she takes her time as a doctor but then to me I feel like the time is not enough. That portal if it can have it [lab results] in advance. (African woman, 50 years old, heterosexual) That (appointment management) would save calling the hospital to make appointments. (African Woman, 54 years old, heterosexual) Yes, it’s (check-in) really better than sitting in queue and not knowing when your name is going to be called. (African woman, 30 years, heterosexual) I guess it’s a good application, a good function (navigation tool) because we are not familiar with every section of the hospital. (White man, 61 years old, heterosexual) | It’s (calendar and notifications) still useful, because there are a number of patients who miss their appointments… (Physician) Speed of registration (using a check-in function), perhaps needing a little less staff for this kind of work, avoiding queues. (Physician) Why is he taking this (medication)? Anyway, it (consultation notes) would help us a lot, that’s for sure, as professionals. (Pharmacist) Everything (should) be in the app in terms of where your appointment is ((navigation tool) … what time, etc. (Clinical coordinator) |

| Responsiveness to patient preferences | Anything additional other than English and French would be good. Especially for elderly people that come in the country and they don’t even have that time to start learning the languages. (African woman, 30 years old, heterosexual) To be able to configure only the things you need because you can have everything there. Maybe it’s overwhelming for people that only want to use a small part. (European man, 28 years old, heterosexual) (I) suggested facial recognition technology but there is a possibility that there are some phones that are not compatible with it. (African man, 40 years old, heterosexual) | It (automated log out) should be automatic because… patients don’t remember to log out. (Nurse) It (account settings) just should be able to enable or disable certain aspects if they want or don’t want it. (Physician) (We should be) able to choose which notifications you are getting so you don’t get bombarded. (Pharmacist) Don’t be afraid to use pictograms, like pictures, to describe what to do. (Social worker) |

| Fulfillment of current or evolving user needs | Not only to have it on your phone but also on your computer so that you can have it send you a text or message to say “Ok, you have medication” or “Your next appointment will be on that date”. (African woman, 31 years old, bisexual) Sort of like chatting (on a chat box) like we do with friends. I am missing that on the portal. (African woman, 50 years old, heterosexual) Yes, ongoing feedback (patient feedback survey) is how we can improve it (a patient portal). (African man, 51 years old, heterosexual) It (appointment management) would engage people in other complementary ways. (White woman, 47 years old, heterosexual) | My personal opinion is that patients would like (PROMs) too because it shows we care about those issues, and they feel actually uncomfortable bringing them up. (Physician) We could have some kind of evaluation of the overall satisfaction with the clinic care and where are the areas where they would like improvement. (Physician) I think it would be useful for the carer to have, for example, a collection of information on the weeks or months that preceded, of data perhaps, of difficulties that the patient encountered. (Nurse) From diabetes to cancer to HIV… (Synchronizing data to other clinics) It could be just a way of improving the medical system and updating it to new technologies. (Pharmacist) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, D.; Lessard, D.; Laymouna, M.A.; Engler, K.; Schuster, T.; Ma, Y.; Kronfli, N.; Routy, J.-P.; Hijal, T.; Lacombe, K.; et al. Understanding the Risks and Benefits of a Patient Portal Configured for HIV Care: Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020314

Chu D, Lessard D, Laymouna MA, Engler K, Schuster T, Ma Y, Kronfli N, Routy J-P, Hijal T, Lacombe K, et al. Understanding the Risks and Benefits of a Patient Portal Configured for HIV Care: Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(2):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020314

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Dominic, David Lessard, Moustafa A. Laymouna, Kim Engler, Tibor Schuster, Yuanchao Ma, Nadine Kronfli, Jean-Pierre Routy, Tarek Hijal, Karine Lacombe, and et al. 2022. "Understanding the Risks and Benefits of a Patient Portal Configured for HIV Care: Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 2: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020314

APA StyleChu, D., Lessard, D., Laymouna, M. A., Engler, K., Schuster, T., Ma, Y., Kronfli, N., Routy, J.-P., Hijal, T., Lacombe, K., Sheehan, N., Rougier, H., & Lebouché, B. (2022). Understanding the Risks and Benefits of a Patient Portal Configured for HIV Care: Patient and Healthcare Professional Perspectives. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 12(2), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020314