Telemedicine in Elderly Hypertensive and Patients with Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

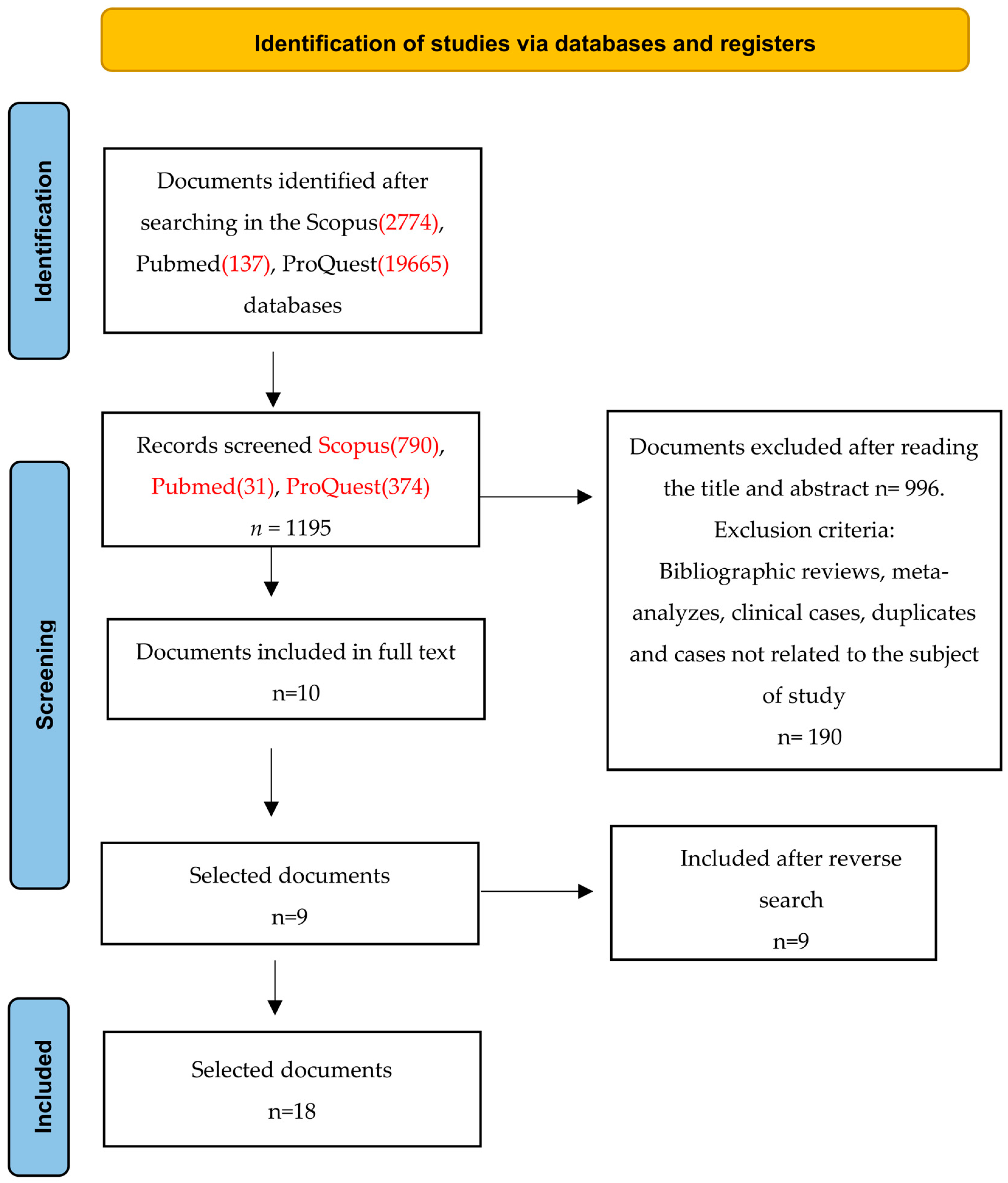

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Data Analysis

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment and Level of Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic of the Studies Included

3.2. Telemedicine, Consult Perception

3.3. Telemedicine in COVID-19 Context

3.4. Telephone vs. Video Consultation

3.5. Doctors’ Use of Telemedicine vs. Presential Attention

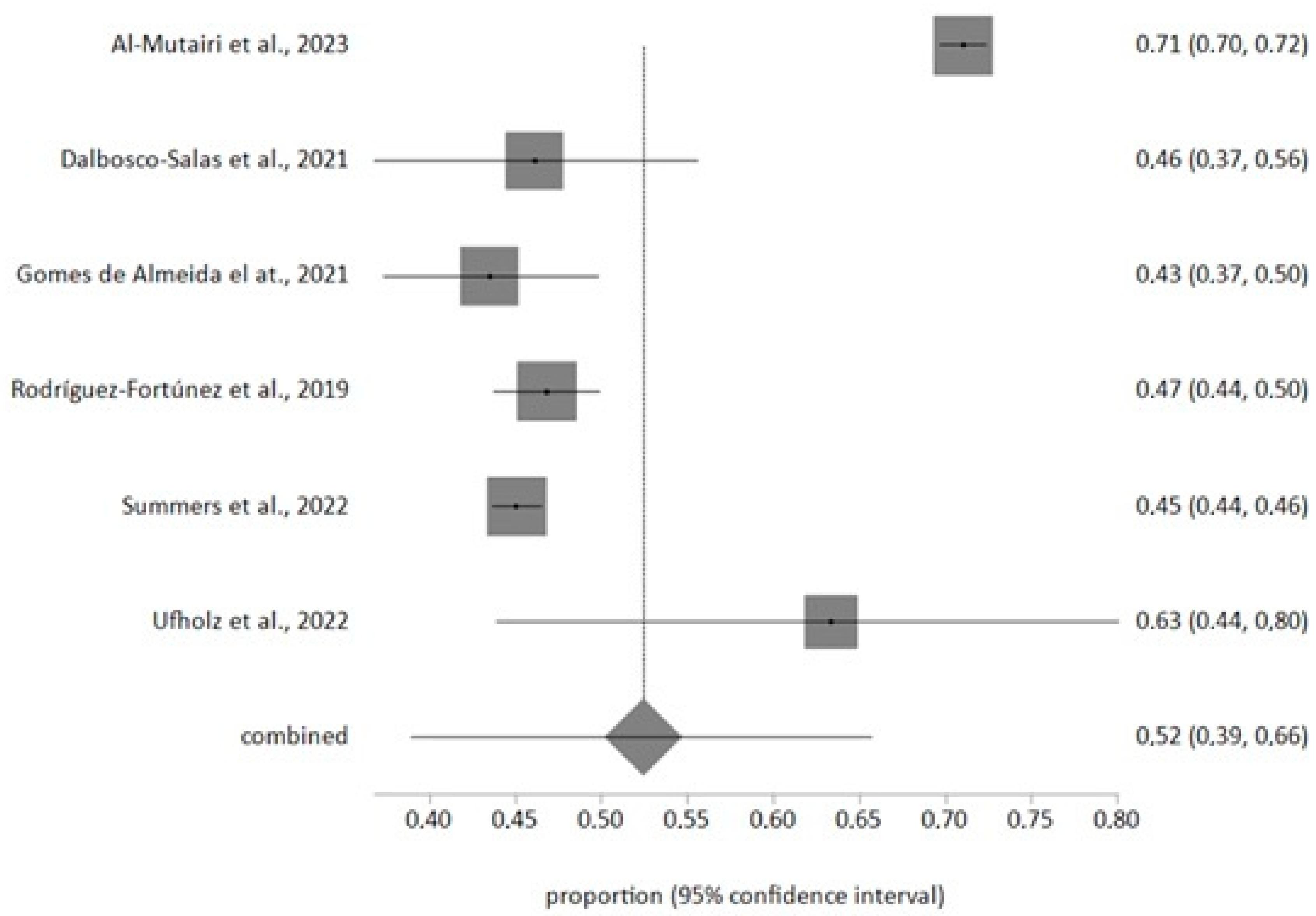

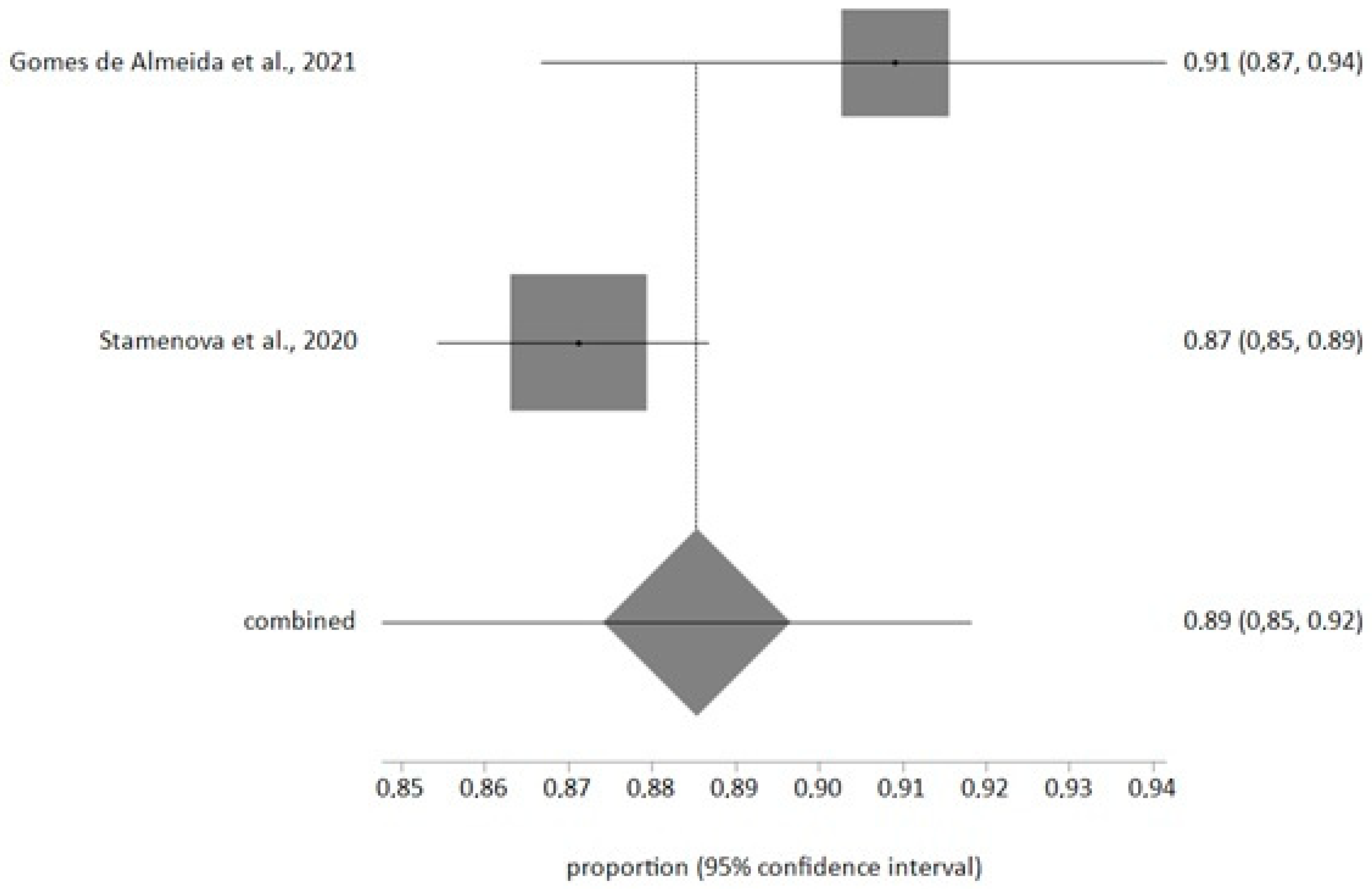

3.6. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Guidance on Routine Immunization Services during COVID-19 Pandemic in the WHO European Region, 20 March 2020 n.d. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2020-1059-40805-55114 (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- CDC. How to Protect Yourself and Others|CDC n.d. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprevent-getting-sick%2Fsocial-distancing.html#stay6ft (accessed on 23 October 2022).

- Guillem, F.C. Opportunities and threats for prevention and health promotion and the PAPPS in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aten. Prim. 2020, 52, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoon, V. Operationalizing virtual visits during a public health emergency. Fam. Pract. Manag. 2020, 27, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hollander, J.E.; Carr, B.G. Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagarapu, J.; Savani, R.C. A brief history of telemedicine and the evolution of teleneonatology. Semin. Perinatol. 2021, 45, 151416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, N.M.; Julius, H.W. Centenary of tele-electrocardiography and telephonocardiography. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.B.; Brady, C.J.; Cavallerano, J.; Abramoff, M.; Barker, G.; Chiang, M.F.; Crockett, C.H.; Garg, S.; Karth, P.; Liu, Y.; et al. Practice Guidelines for Ocular Telehealth-Diabetic Retinopathy, Third Edition—PubMed (nih.gov). Telemed. J. e-Health 2020, 26, 495–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullington, H.; Kitterick, P.; Darnton, P.; Finch, T.; Greenwell, K.; Riggs, C.; Weal, M.; Walker, D.M.; Sibley, A. Telemedicine for Adults with Cochlear Implants in the United Kingdom (CHOICE): Protocol for a Prospective Interventional Multisite Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e27207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotanda, H.; Liyanage-Don, N.; Moran, A.E.; Krousel-Wood, M.; Green, J.B.; Zhang, Y.; Nuckols, T.K. Changes in blood pressure outcomes among hypertensive individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic: A time series analysis in three US healthcare organizations. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2733–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrioli, J.; Santangelo, M.; Luciani, A.; Toscani, S.; Zucchi, E.; Giovannini, G.; Martinelli, I.; Cecoli, S.; Bigliardi, G.; Scanavini, S.; et al. TeleNeurological evaluation and Support for the Emergency Department (TeleNS-ED): Protocol for an open-label clinical trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19, Information for Healthcare Professionals|CDC n.d. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Reuter, H.; Jordan, J. Status of hypertension in Europe. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2019, 34, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varandani, S.; Nagib, N.D. Evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on monthly trends in primary care. Cureus 2022, 14, e28353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omboni, S.; McManus, R.J.; Bosworth, H.B.; Chappell, L.C.; Green, B.B.; Kario, K.; Logan, A.G.; Magid, D.J.; Mckinstry, B.; Margolis, K.L.; et al. Evidence and recommendations on the use of telemedicine for the management of arterial hypertension: An international expert position paper. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1368–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, L.C.; Lawson, B.K.; Roman, C.; Thompson, B.; Biggs, C.; Rutter, H.; Lewis-Jones, M.; Ede, J.; Tarassenko, L.; Farmer, A.; et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring using telemedicine: Proof-of-concept cohort and failure modes and effects analyses. Wellcome Open Res. 2022, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howick, J.; Chalmers, I.; Glasziou, P.; Greenhalg, T.; Heneghan, C.; Liberati, A.; Moschetti, I.; Phillips, B.; Thornton, H. The Oxford Levels of Evidence. 2011. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/2016/05/ocebmlevels-of-evidence (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Lee, S.Y.; Chun, S.Y.; Park, H. The impact of COVID-19 protocols on the continuity of care for patients with hypertension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, C.; Griffiths, F.; Cave, J.; Panesar, A. Understanding the security and privacy concerns about the use of identifiable health data in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Survey study of public attitudes toward COVID-19 and data-sharing. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e29337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, L.A.; Kallan, M.J.; Julien, H.M.; Haynes, N.; Khatana, S.A.M.; Nathan, A.S.; Snider, C.; Chokshi, N.P.; Eneanya, N.D.; Takvorian, S.U.; et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2031640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-de Almeida, S.; Marabujo, T.; do Carmo-Gonçalves, M. Telemedicine satisfaction of primary care patients during COVID-19 pandemics. Semergen 2021, 47, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Fortúnez, P.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Fornos-Pérez, J.A.; Martínez-Martínez, F.; de Paz, H.D.; Orera-Peña, M.L. Cross-sectional study about the use of telemedicine for type 2 diabetes mellitus management in Spain: Patient’s perspective. The EnREDa2 Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopelt, K.; Avni, N.; Haimov-Sadikov, Y.; Golan, I.; Davidovitch, N. Telemedicine and eHealth literacy in the era of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in a peripheral clinic in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barayev, E.; Shental, O.; Yaari, D.; Zloczower, E.; Shemesh, I.; Shapiro, M.; Glassberg, E.; Magnezi, R. WhatsApp Tele-Medicine—Usage patterns and physicians views on the platform. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.E.; Lai, A.Y.; Gupta, A.; Nguyen, A.M.; Berry, C.A.; Shelley, D.R. Rapid transition to telehealth and the digital divide: Implications for primary care access and equity in a post-COVID era. Milbank Q. 2021, 99, 340–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Fagerlund, A.J. Patients’ use and experiences with e-consultation and other digital health services with their general practitioner in Norway: Results from an online survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, R.P.; Stevermer, J.J. Disparities in use of telehealth at the onset of the COVID-19 public health emergency. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 29, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Shani, M.; Boaz, M.; Lahad, A.; Vinker, S.; Birk, R. Opportunities and challenges in delivering remote primary care during the Coronavirus outbreak. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.; Kosowan, L.; LaBine, L.; Shenoda, D.; Katz, A.; Abrams, E.M.; Halas, G.; Wong, S.T.; Talpade, S.; Kirby, S.; et al. Characterizing the use of virtual care in primary care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juergens, N.; Huang, J.; Gopalan, A.; Muelly, E.; Reed, M. The association between video or telephone telemedicine visit type and orders in primary care. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mutairi, A.M.; Alshabeeb, M.A.; Abohelaika, S.; Alomar, F.A.; Bidasee, K.R. Impact of telemedicine on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus during the COVID-19 lockdown period. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1068018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ufholz, K.; Sheon, A.; Bhargava, D.; Rao, G. Telemedicine Preparedness Among Older Adults with Chronic Illness: Survey of Primary Care Patients. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e35028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairat, S.; Meng, C.; Xu, Y.; Edson, B.; Gianforcaro, R. Interpreting COVID-19 and Virtual Care Trends: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenova, V.; Agarwal, P.; Kelley, L.; Fujioka, J.; Nguyen, M.; Phung, M.; Wong, I.; Onabajo, N.; Bhatia, R.S.; Bhattacharyya, O. Uptake and patient and provider communication modality preferences of virtual visits in primary care: A retrospective cohort study in Canada. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbosco-Salas, M.; Torres-Castro, R.; Rojas Leyton, A.; Morales Zapata, F.; Henríquez Salazar, E.; Espinoza Bastías, G.; Beltrán Díaz, M.E.; Tapia Allers, K.; Mornhinweg Fonseca, D.; Vilaró, J. Effectiveness of a Primary Care Telerehabilitation Program for Post-COVID-19 Patients: A Feasibility Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Huang, J.; Graetz, I.; Muelly, E.; Millman, A.; Lee, C. Treatment and follow-up care associated with patient-scheduled primary care telemedicine and in-person visits in a large integrated health system. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2132793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laddu, D.; Ma, J.; Kaar, J.; Ozemek, C.; Durant, R.W.; Campbell, T.; Welsh, J.; Turrise, S. Health behavior change programs in primary care and community practices for cardiovascular disease prevention and risk factor management among midlife and older adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, E533–E549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Conejo, T.; et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, e187–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsey, M.D.; Nelson, A.J.; Green, J.B.; Granger, C.B.; Peterson, E.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Pagidipati, N.J. Guidelines for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: JACC Guideline Comparison. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Chen, W.; Gao, Z.; Lv, X.; Sun, Y.; Yang, X.; Shan, H. Effectiveness of telemedicine for cardiovascular disease management: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 12831–12844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Majumder, S.; Kumar, S.; Subramaniam, S.; Li, X.; Khedri, R.; Mondal, T.; Abolghasemian, M.; Satia, I.; Deen, M.J. A wearable tele-health system towards monitoring COVID-19 and chronic diseases. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 15, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.; Davey, A.R.; Magin, P. Telehealth for Australian general practice: The present and the future. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2022, 51, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo de Albornoz, S.; Sia, K.L.; Harris, A. The effectiveness of teleconsultations in primary care: Systematic review. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, V.; Donaghy, E.; Parker, R.; McNeilly, H.; Atherton, H.; Bikker, A.; Campbell, J.; McKinstry, B. Comparing the content and quality of video, telephone, and face-to-face consultations: A non-randomised, quasi-experimental, exploratory study in UK primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2019, 69, E595–E604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Scott, R.E.; Mars, M. WhatsApp in clinical practice-the challenges of record keeping and storage. A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallarés Carratalá, V.; Górriz-Zambrano, C.; Llisterri Caro, J.L.; Gorriz, J.L. The COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity to change the way we care for our patients. Semergen 2020, 46, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Berg, C.; Thompson, J.; Dean, K.; Yuan, T.; Nallamshetty, S.; Tong, I. Effective access to care in a crisis period: Hypertension control during the COVID-19 pandemic by telemedicine. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Anstey, D.E.; Grauer, A.; Metser, G.; Moise, N.; Schwartz, J.; Kronish, I.; Abdalla, M. The impact of telemedicine visits on the controlling high blood pressure quality measure during the COVID-19 pandemic: Retrospective cohort study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e32403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassavou, A.; Wang, M.; Mirzaei, V.; Shpendi, S.; Hasan, R. The association between smartphone app-based self-monitoring of hypertension-related behaviors and reductions in high blood pressure: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e34767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad Ali, S.; Bin Arif, T.; Maab, H.; Baloch, M.; Manazir, S.; Jawed, F.; Kumar Ochani, R. Global Interest in Telehealth During COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of Google Trends™. Cureus 2020, 12, e10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Weekly Epidemiological Updates and Monthly Operational Updates. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed on 14 September 2023).

- Saigí-Rubió, F.; Nascimento, I.J.B.D.; Robles, N.; Ivanovska, K.; Katz, C.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Ortiz, D.N. The current status of telemedicine technology use across the World Health Organization European Region: An overview of systematic reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e40877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.; Young, J.; King, V.; Meadows, J. Patient expectations for synchronous telerehabilitation visits: A survey study of telerehabilitation-naive patients. Telemed. J. e-Health 2022, 28, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, G.; Assaad, S.; Chaaya, M. Hypertension prevalence and control among community-dwelling lebanese older adults. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020, 22, 1727–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muli, S.; Meisinger, C.; Heier, M.; Thorand, B.; Peters, A.; Amann, U. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in older people: Results from the population-based KORA-age 1 study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabi, D.M.; McBrien, K.A.; Sapir-Pichhadze, R.; Nakhla, M.; Ahmed, S.B.; Dumanski, S.M.; Butalia, S.; Leung, A.A.; Harris, K.C.; Cloutier, L.; et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 Comprehensive Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and Treatment of Hypertension in Adults and Children. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 596–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, e13–e115, Erratum in Hypertension 2018, 71, e140–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahat, A.; Shatz, Z. Telemedicine in clinical gastroenterology practice: What do patients prefer? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 1756284821989178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year, Country | Type of Study | Sample | Intervention | Main Findings | Conclusions | EL/RG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Mutairi et al., 2023 (Saudi Arabia) [32] | Retrospective, cohorts | 4266 patients | Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Saudi Arabia (March 2020 to June 2020) shifted routine in-person care for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DMT2) to telemedicine. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact telemedicine had during this period on glycemic control (HbA1c) in patients with DMT2 and with AHT and older as a comorbilities in almost 50% of patients. | The patient demographics consisted primarily of Saudis (97.7%), with 59.7% being female and 56.4% aged ≥60 years. The prevalence of obesity was 63.8%, dyslipidemia was 91%, and hypertension was 70%. The mean HbA1c for all patients showed a slight increase from 8.52% ± 1.5% before the lockdown to 8.68% ± 1.6% after the lockdown. Among the patients, n = 1064 (24.9%) witnessed a decrease in HbA1c by ≥0.5%, n = 1574 patients had an increase in HbA1c by ≥0.5% (36.9%), and n = 1628 patients experienced an HbA1c change of <0.5% in either direction (38.2%). Notably, a greater percentage of males demonstrated significant improvements in glycemia compared to females (28.1% vs. 22.8%, p < 0.0001), as did individuals below the age of 60 years (28.1% vs. 22.5%, p < 0.0001). Hypertensive individuals were less likely to experience glycemic improvement than non-hypertensive individuals (23.7% vs. 27.9%, p = 0.015). Patients on sulfonylureas exhibited a higher proportion of HbA1c improvement (42.3% vs. 37.9%, p = 0.032), while patients on insulin had higher HbA1c levels (62.7% vs. 56.2%, p = 0.001). The changes in HbA1c were independent of BMI, hyperlipidemia, disease duration, and cardiac or renal conditions. | Telemedicine proved effective in providing care to patients with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 lockdown; 63.1% of patients maintaining their HbA1c levels and achieving better glycemic control. Improvement was notably higher among males compared to females. Despite these advances, HbA1c levels remained persistently elevated in these patients before and after blockade. Although the improvement was greater among males than females, HbA1c levels remained elevated in these patients before and after blockade. This problem is probably due to factors related to healthy lifestyle, age, education, and hypertension. | 2a/B |

| Barayev et al., 2021 (Israel) [25] | Cross-sectional | 201 doctors | Cross-sectional study based on an anonymous web survey conducted among family doctors and hospital physicians working in the Israel Defence Forces Medical Corps, during September and October 2019. | A total of 153 participants were family physicians and 48 were hospital specialists. WhatsApp® is used daily in professional settings by 86.9% of PCPs and by 86.5% of hospital specialists. The additional workload, potential breaches of patient confidentiality, and lack of complete documentation of consultations were the main concerns expressed about the app. However, 60.7% of PCPs and 95.7% of specialists stated that it enabled them to reduce in-person consultations at least once a week. | In the social distancing required by COVID-19, WhatsApp® offers a simple and readily available platform for consultations between healthcare providers, making some in-person appointments unnecessary. However, some issues remain to be addressed, such as patient confidentiality, the possible lack of documentation of patients’ medical history, and the need to compensate those who provide telemedicine services after business hours. | 2c/B |

| Chang et al., 2021 (USA) [26] | Cross-sectional | 1100 doctors | Analysis of telemedicine use and barriers to use in small primary care practices. The information comes from surveys conducted by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York University. The purpose of these surveys was to understand the strategies and responses of primary care practices in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. The collection was conducted between 10 April and 18 June 2020. | Healthcare practitioners in regions characterized by high Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) were nearly twice as likely to predominantly employ telephones as their primary telemedicine mode (41.7% vs. 23.8%; p < 0.001), compared to their counterparts in low SVI regions. Conversely, video-based telemedicine was predominantly utilized by 18.7% of providers in high SVI areas, contrasting with 33.7% in low SVI areas (p < 0.001). Moreover, healthcare providers in high SVI areas encountered more patient-related barriers but fewer obstacles on the provider’s end, as opposed to those in low SVI areas. | Telemedicine became an important mode of primary care delivery in New York City during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the shift towards telemedicine was not uniform across all communities. To promote more equitable access in this realm, policy adjustments should aim to tackle the impediments experienced by underserved populations, including both patients and caregivers. | 2c/B |

| Dalbosco-Salas et al., 2021 (Chile) [36] | Cohorts | 115 patients | The study assessed the efficacy of a telerehabilitation program implemented within primary care for post-COVID-19 patients. An observational, prospective study was carried out across seven primary care centers in Chile, encompassing adult patients (>18 years) with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. | The telerehabilitation program comprised 24 sessions of supervised exercise training conducted at patients’ homes. Its effectiveness was evaluated using the 1-min Sit-to-Stand Test (1-min STST), SF-36 questionnaire, fatigue levels, and dyspnea symptoms before and after the intervention. The study enrolled 115 patients, with 55.4% being female, and a mean age of 55.6 ± 12.7 years. Among them, 57 patients (50%) had a history of hospitalization, and 35 (30.4%) were ICU admissions. Following the intervention, the 1-min STST showed improvement, increasing from 20.5 ± 10.2 (53.1 ± 25.0% predicted) to 29.4 ± 11.9 (78.2 ± 28.0% predicted) repetitions (p < 0.001). Additionally, the SF-36 global score demonstrated a significant enhancement, rising from 39.6 ± 17.6 to 58.9 ± 20.5. | Fatigue and dyspnea exhibited significant improvement post-intervention. Despite the lack of a control group, this report demonstrated the viability and effectiveness of a tele-rehabilitation program implemented within primary healthcare. It notably enhanced physical capacity, quality of life, and symptom management in adult survivors of COVID-19. | 2a/B |

| Dopelt et al., 2021 (Israel) [24] | Cross-sectional | 156 doctors | This study examined the extent of telemedicine use and the relationship between eHealth literacy and satisfaction with telemedicine use during the pandemic. A total of 156 patients at a clinic in southern Israel completed an online questionnaire. | In the sample, 86% of participants could use the Internet to obtain health information, but only one-third felt confident in using it to make health decisions. Further, 93% used the Internet for technical actions, such as renewing prescriptions or making appointments. Only 38% used telemedicine for consultations or treatment sessions. eHealth literacy and satisfaction were positively associated with telemedicine use (rp = 0.39, p < 0.001). Although respondents understood the benefits of telemedicine, they were neither satisfied with nor interested in online sessions once the COVID-19 epidemic became less acute, preferring in-person meetings. Young people and academics benefit most from telemedicine, creating gaps in use and potentially increasing healthcare inequality. | Intervention programs should be developed, especially among vulnerable populations, to strengthen e-health literacy and remove barriers that may generate scepticism about the use of telemedicine, during and after the pandemic. | 2c/B |

| Eberly et al., 2020 (USA) [21] | Retrospective, cohorts | 148,402 patients with scheduled appointments; 80,780 appointments kept. | The association between video and telephone consultations with gender, race, language, and socioeconomic status was studied, from 16 March to 11 May 2020. | Of 78,539 consultations, 35,824 were by video and 42,715 by telephone. Lower use of telemedicine was associated with: 1-Advanced age OR 95% CI 0.85 (0.83–0.88). 2-Asian race OR 95% CI 0.69 (0.66–0.73). 3-Preferred language other than English OR 95% CI 0.89 (0.78–0.9). 4-Medicaid insured OR 95% CI 0.93 (0.89–0.97). Lower use of video visits was associated with 1-Advanced age OR 95% CI 0.79 (0.76–0.82) 2-Female sex OR 95% CI 0.92 (0.9–0.95) 3-Black race OR 95% CI 0.65 (0.62–0.68) 4-Hispanic Race OR 95% CI 0.9 (0.83–0.97) 5-Low socioeconomic level OR 95% CI 0.57 (0.54–0.60) (less than 50,000 USD) and OR 95% CI 0.89 (0.85–0.92) (50,000–100,000 USD). | During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients who were older, Asian, or non-English speaking made less use of telemedicine, while older patients, women, African Americans, Latinos, and poorer patients used video calls more. Access to telemedicine is unequal, which should be investigated further. | 2a/B |

| Gomes-de Almeida et al., 2021 (Portugal) [22] | Cross-sectional | 253 patients | Patient satisfaction was studied on 4–5 January 2020 using a questionnaire scored on a Likert scale. | In the sample, 70.6% of patients prefer telemedicine. Consultations for diabetes fell by 50.1% and for hypertension by 94.1%, compared with pre-COVID. Telemedicine consultations rose by 61.9%. | The vast majority of telemedicine users during the COVID-19 pandemic were satisfied with the results. | 2c/B |

| Juergens et al., 2022 (USA) [31] | Cross-sectional | 809,146 completed adult primary care telemedicine encounters. | In this study, patients who autonomously scheduled and successfully participated in telemedicine appointments with their designated primary care provider or an alternate available primary care provider within the same medical group were identified. The data collection encompassed the period from 1 April 2020 to 31 October 2020, during which physical distancing measures due to COVID-19 were enforced. | A total of 273,301 encounters were analyzed, comprising 86,676 (41.5%) video visits and 122,051 (58.5%) telephone visits. In terms of specific diagnosis groups, skin and soft tissue conditions exhibited the highest proportion of video visits (59.7%), whereas mental health conditions had the highest proportion of telephone visits (71.1%). Upon covariate adjustment, the overall rates of medication orders (46.6% vs. 44.5%), imaging orders (17.3% vs. 14.9%), lab orders (19.5% vs. 17.2%), and antibiotic orders (7.5% vs. 5.2%) were notably elevated during video visits in comparison to telephone visits (p < 0.05). The most significant difference within diagnosis groups was observed in skin and soft tissue conditions, where the rate of medication orders during video visits was 9.1% higher than during telephone visits (45.5% vs. 36.5%, p < 0.05). | The study showed notable and statistically significant variations in clinician orders based on the type of visit in telemedicine encounters, particularly for prevalent primary care conditions. The results strongly indicate that, for specific conditions, the visual information provided during video visits can facilitate clinical assessment and treatment decisions. | 2c/B |

| Kaufman-Shriqui et al., 2022 (Israel) [29] | Cross-sectional | 159 family doctors | The study was conducted using a 47-item online Google Crosswalk survey, via the Israel Association of Family Physicians mailing list, between 31 March and 5 May 2020. The questionnaire obtained demographic data, physician characteristics, and information on the use and perceived quality of telemedicine. | The use of telephone consultation by physicians was inversely associated with their prescribing antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic (OR 0.30 95% CI (0.134–0.688) p = 0.004) and with their requesting more blood tests during the pandemic (OR = 0.06 95% CI (0.008–0.378) p = 0.003). | Telemedicine has considerable promise in primary care and has great potential for improvement. However, the interpersonal challenges need to be thoroughly understood so that physicians can receive personalized coaching. Further randomized trials are needed, including patient-reported outcomes. Research is also needed on the utility, cost, and cost-effectiveness of telemedicine for follow-up, prescribing, and additional referrals. | 2c/B |

| Khairat et al., 2020 (USA) [34] | Cohorts | 733 virtual visits | The objective of this study was to investigate the patterns of confirmed COVID-19 cases in North Carolina and to comprehend the trends in virtual visits associated with symptoms of COVID-19. | By 18 March 2020, a total of 92 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 733 virtual visits were documented. Out of these virtual visits, 257 (35.1%) were linked to symptoms resembling COVID-19. Among these visits, the majority were by females (178 visits, 69.2%). Patients aged between 30 and 39 years (n = 67, 26.1%) and 40 and 49 years (n = 64, 24.9%) constituted half of the total cases. Remarkably, almost 96.9% (n = 249) of the COVID-like encounters were reported within the state of North Carolina. The study underscores the efficiency of virtual care in effective triage, especially in counties with a high incidence of COVID-19 cases. Furthermore, it affirms that the disease spreads extensively in densely populated regions and areas with major airports. | The utilization of virtual care holds significant promise in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. It has the potential to diminish emergency room visits, preserve critical healthcare resources, and mitigate the spread of COVID-19 by enabling remote patient treatment. The findings from this study strongly advocate for the widespread integration of virtual care within global health systems as a crucial approach in addressing the challenges posed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. | 2a/B |

| Lee et al., 2022 (Korea) [19] | Cohorts | 5,791,812 hypertensive patients | The aim of this study was to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the continuity of care of hypertensive patients, considering the use of telemedicine. Study data were obtained from insured physicians in South Korea, for 2019 and 2020. | After the outbreak of COVID-19 and the increased use of telemedicine, in-person consultations decreased by 0.293 days (p < 0.0001) to 0.333 days per patient. | COVID-19 protocols did not affect treatment continuity for patients with hypertension, but did affect the frequency of outpatient visits. Medical care was not interrupted, but there was a significant difference in the type of medical care provided, with the inclusion of telemedicine. | 2a/B |

| Pierce and Stevermer 2020 (USA) [28] | Cross-sectional | 7742 family doctors | The aim of the study was to study family medicine visits at a single US institution in the initial month of the COVID-19 public health emergency (17 March to 16 April 2020), comparing the demographics of patients using telemedicine with those using in-person visits during the same period, and the demographics of those using full audio and video with those using audio only. | The likelihood of any telemedicine visit in the first 30 days of its expansion was higher for women (OR 1.15 95% CI 1.04–1.26), persons aged 65 years or older (OR 1.21 95% CI 1.05–1.40), self-pay patients (OR 1.26 95% CI 1.04–1.52), and those with Medicaid (OR 1.29 95% CI 1.04–1.61) or Medicare (OR 1.37 95% CI 1.18–1.60) as primary payers. The likelihood of a telemedicine visit was lower for rural residents (OR 0.81 95% CI 0.74–0.90), persons of African American race (OR 0.65 95% CI 0.56–0.75) or of other races (OR 0.64 95% CI 0.50–0.82). The likelihood of a complete telemedicine visit with audio and video was lower for patients who were older (OR 0.27 95% CI 0.21–0.33), of African American race (OR 0.72 95% CI 0.55–0.93), from urban areas (OR 1.36 95% CI 1.14–1.61), or self-pay, or with Medicaid (OR 0.36 95% CI 0.26–0.51) or Medicare (OR 0.79 95% CI 0.64–0.99). | Age, race, area of residence, and insurance provision are significant variables for the use of telemedicine in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. | 2c/B |

| Rodríguez-Fortúnez et al., 2019 (Spain) [23] | Cross-sectional | 1036 patients | Observational, cross-sectional study conducted among diabetics over 18 years of age with data for one year, conducted between 18 April and 5 May 2016. | Blood glucose values were recorded by 85.9% of patients, but data for lifestyle habits by only 14.4%. Previous experience with telemedicine was reported by 9.8% of patients, of whom 70.5% were satisfied with the service while 73.5% considered that the use of telemedicine had optimized their DM2 management. However, most remarked on areas for improvement, such as ease of use (81.4%), interaction with the medical team (78.4%), and the time required for data recording/transfer (78.4%). Experienced patients had better perceptions of the usefulness of telemedicine than naïve patients, for all aspects considered (p < 0.05). | In Spain, almost 10% of patients with DM2 have experience with telemedicine, and it is well accepted, especially when based on glucometers. However, to expand the use of telemedicine, easier and time-saving programs for patient–physician interaction should be implemented. | 2c/B |

| Singer et al., 2022 (Canada) [30] | Retrospective, cohorts | 142,616 patients 154 primary care providers | This study analyzed the characteristics of virtual visits, providing insights into the utilization and users of virtual care within primary care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically from 14 March 2020, to 30 June 2020. | Between 14 March 2020 and 30 June 2020, a total of 146,372 visits were administered by 154 primary care providers. Among these, 33.6% were conducted via virtual care. Female patients (OR 1.16, CI 1.09–1.22), patients with ≥3 comorbidities (OR 1.71, CI 1.44–2.02), and patients with ≥ 10 prescriptions (OR 2.71, 2.2–1.53) had a higher likelihood of having at least one virtual care visit compared to male patients, those with no comorbidities, and those with no prescriptions. Notably, the study found no significant difference in the number of follow-up visits provided as a clinic visit compared to a virtual care visit (8.7% vs. 5.8%) (p = 0.6496). | In the early stages of the pandemic restrictions, about a third of visits were conducted virtually. Patients with a higher number of comorbidities and prescriptions were the ones predominantly utilizing virtual care, suggesting that patients with chronic disease requiring ongoing care utilized virtual care. Virtual care as a primary care visit type continues to evolve. Ongoing provision of virtual care can enhance quality, patient-centered care moving forward | 2a/B |

| Stamenova et al., 2020 (Canada) [35] | Retrospective, cohorts | 14,291 patients 326 primary care providers | Restrospective cohorts study with the aim to assess the adoption of a virtual visit platform in primary care, investigate the preferences of patients and physicians regarding virtual communication methods, and provide insights into visit characteristics and patient experiences with the care provided. | A total of 44% of registered patients and 60% of registered providers actively utilized the platform. Among the patients, 51% successfully completed at least one virtual visit. Interestingly, a vast majority of these virtual visits (94%) primarily utilized secure messaging. Notable patient requests included medication prescriptions (24%) and follow-up from a previous appointment (22%). Conversely, providers frequently used virtual visits to follow up on test results (59%). Impressively, 81% of virtual visits, according to providers, required no further follow-up for the respective issue. Moreover, an overwhelmingly positive response was received, with 99% of patients expressing their intent to use virtual care services again. | Although the availability of primary care video visit services is on the rise, this study revealed a noteworthy preference for secure messaging over video among both patients and providers in rostered practices. Contrary to concerns about potential overuse of virtual visits, it was observed that virtual visits, especially when patients connected with their designated primary care provider, often substituted in-person visits without overwhelming physicians with excessive requests. This approach shows promise in enhancing access and maintaining continuity in primary care services. | 2a/B |

| Summers et al., 2022 (UK) [20] | Cohorts | 4764 patients | Study conducted by email invitation (11,213 sent) of patients over 18 years of age and registered at Diabetes.co.uk. Data were collected 6–31 August 2020, including quantitative information on demographic characteristics, COVID-19 diagnosis and symptoms, privacy and custody of pre- and post-COVID-19 health data, and COVID-19 blocking behavior. The study aim was to determine patients’ willingness to share health data during the COVID-19 pandemic. | N(1) DMT2 = 2974 = 62.7%. N(2) AHT = 2147 = 45.2% N(3) DMT1 = 1299 = 27.4%. A positive correlation was observed between concern about the future use of clinical data and concern about data access (R = 0.916; p = 0.01). There was a strong correlation between concern about the need for stronger legislation and concern about the reuse of shared health data (R = 0.636 p = 0.01). | Data sensitivity is highly contextual. Most participants are more comfortable sharing anonymized rather than personally identifiable data. Willingness to share data also depends on the receiving agency; trust is a key issue, in particular, concerning who may access shared personal health data and how it may be used. | 2a/B |

| Ufholz et al., 2023 (USA) [33]. | Cross-sectional | 30 patients | The objective of this study was to conduct a survey among elderly primary care patients, focusing on their readiness for telemedicine. This included assessing their familiarity with Internet usage, possession of Internet-capable devices, past experiences, and concerns regarding telemedicine, as well as identifying perceived barriers. The findings from this survey were utilized to develop a telemedicine preparedness training program. The patients were 65–81 years old. | The majority of participants (21 out of 30, 70%) stated that they possessed a device suitable for telemedicine and utilized the Internet. However, approximately half of them had only one connected device, with messaging and video calling being the applications most frequently utilized. Email usage was minimal, and no one used online shopping or banking services. Merely 7 patients had engaged in telemedicine appointments. Telemedicine users tended to be younger than nonusers and utilized a greater range of Internet functions. Only 2 individuals reported encountering issues during their telemedicine sessions (related to technology and privacy). Almost all respondents acknowledged the advantages of telemedicine in terms of avoiding travel and reducing exposure to COVID-19. The most prevalent concerns were the potential loss of the doctor–patient connection and the inability to undergo a physical examination. | The majority of elderly individuals mentioned owning devices suitable for telemedicine; however, their Internet usage patterns did not validate the sufficiency of their devices or skills for telemedicine. While doctor–patient discussions could assist in addressing telemedicine apprehensions, it is imperative to also tackle gaps in device functionality and digital proficiency. | 2c/B. |

| Zanaboni and Fagerlund, 2020 (Norway) [27] | Cross-sectional | 2043 patients | An online survey obtained quantitative and qualitative data to determine: (1) user characteristics; (2) use; (3) experiences, perceived benefits and satisfaction; and (4) time spent using telemedicine services. Conducted from January 2017 to April 2018. | Women, young adults, and digitally active citizens with higher education were most likely to use telemedicine. A significant 80% of individuals found it simpler and more efficient to schedule appointments electronically compared to using the phone. An impressive 90% of the surveyed participants believed that renewing a prescription electronically was a hassle-free process. Additionally, 76% stated that managing their medications electronically provided them with a clearer understanding, and a notable 46% reported higher adherence to their prescribed medication regimen. For non-clinical visits, 60% of respondents found emails easier than communicating by phone. For clinical consultations, 72% agreed that electronic consultation improved follow-up, and 58% associated it with better treatment. These users were very satisfied with telemedicine services and would recommend them. The main benefit cited was time saving, which was confirmed by an objective comparison of time spent using telemedicine services vs. conventional approaches. | In Norway, users of e-consultation with family doctors and other digital health services are generally satisfied and consider these tools effective and efficient options to the usual forms of consultation. | 2c/ B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quesada-Caballero, M.; Carmona-García, A.; Chami-Peña, S.; Caballero-Mateos, A.M.; Fernández-Martín, O.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Romero-Bejar, J.L. Telemedicine in Elderly Hypertensive and Patients with Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6160. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196160

Quesada-Caballero M, Carmona-García A, Chami-Peña S, Caballero-Mateos AM, Fernández-Martín O, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Romero-Bejar JL. Telemedicine in Elderly Hypertensive and Patients with Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(19):6160. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196160

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuesada-Caballero, Miguel, Ana Carmona-García, Sara Chami-Peña, Antonio M. Caballero-Mateos, Oscar Fernández-Martín, Guillermo A. Cañadas-De la Fuente, and José Luis Romero-Bejar. 2023. "Telemedicine in Elderly Hypertensive and Patients with Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 19: 6160. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196160

APA StyleQuesada-Caballero, M., Carmona-García, A., Chami-Peña, S., Caballero-Mateos, A. M., Fernández-Martín, O., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., & Romero-Bejar, J. L. (2023). Telemedicine in Elderly Hypertensive and Patients with Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(19), 6160. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196160