Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Serotonin Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics

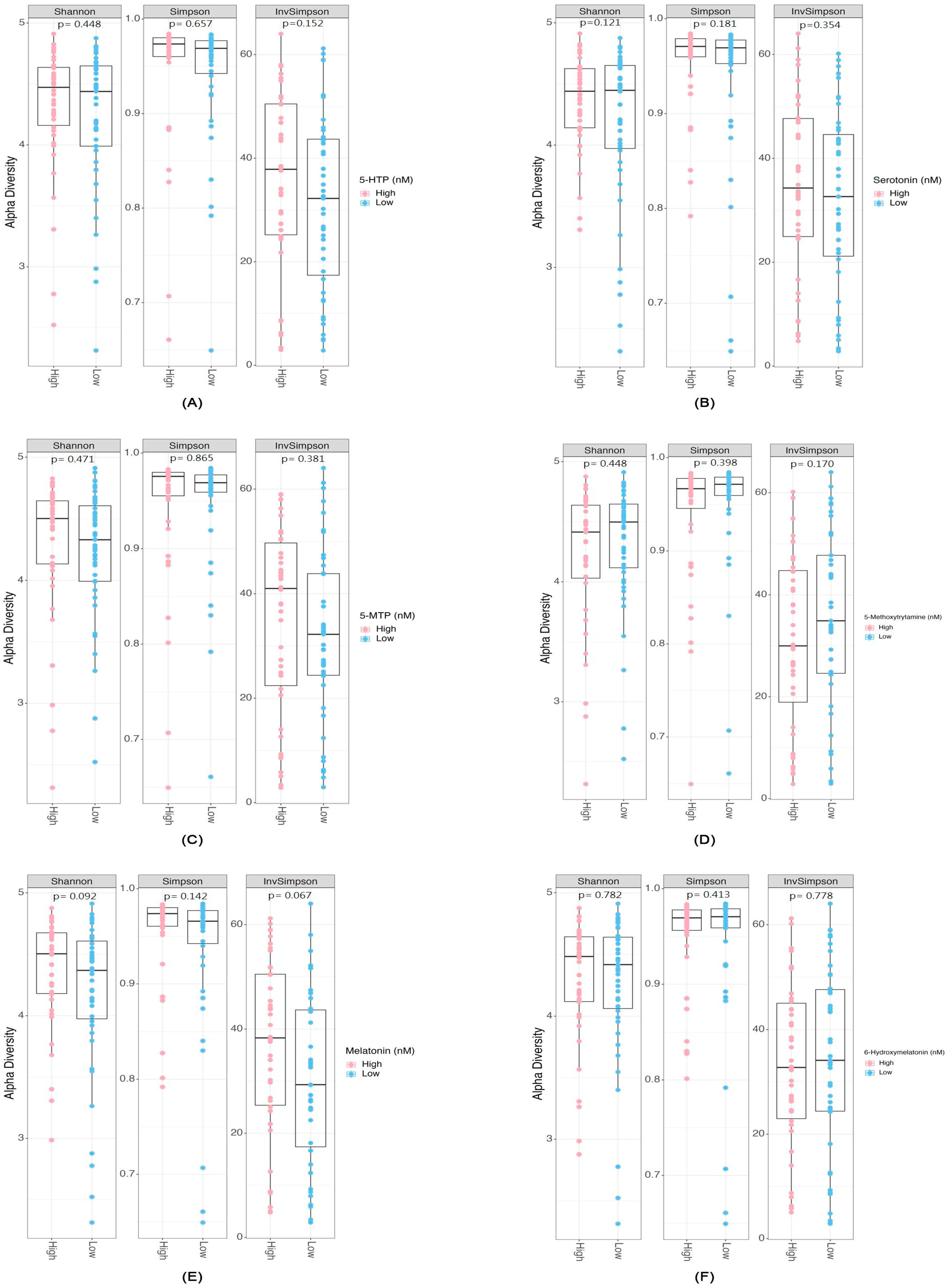

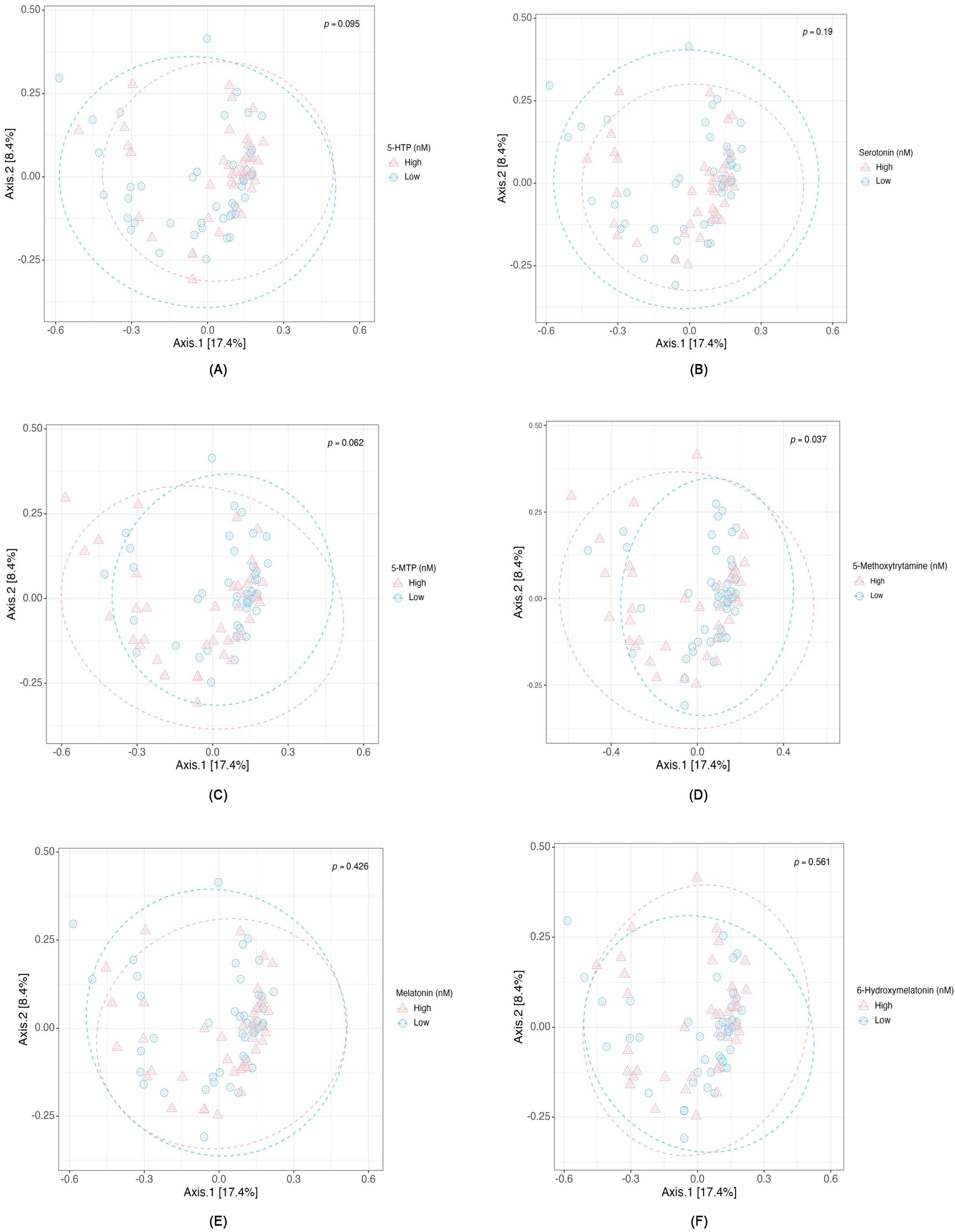

2.2. Differential Abundance and Diversity of Gut Microbiota in Relation to Serotonin-Associated Metabolite Concentrations

2.3. Associations Between Serotonin Concentration, Microbial Composition, and Metabolic Pathways

2.4. Secondary Exploratory Analyses for Additional Serotonin Pathway Metabolites

3. Discussion

3.1. Microbial Diversity and Serotonin Pathway-Associated Metabolites

3.2. Species Associated with Metabolites Involved in Serotonin Pathway

3.3. Gut Metabolic Modules and Serotonin Pathway Metabolites Relationship

3.4. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Comorbidities and Laboratory and Clinical Variables

4.3. Serotonin Pathway-Associated Metabolite Measurement

4.4. Microbiome Analysis

4.5. Bioinformatics and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chao, Y.T.; Lin, Y.K.; Chen, L.K.; Huang, P.; Hsu, Y.C. Role of the gut microbiota and their metabolites in hemodialysis patients. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.K.; Wu, P.H.; Chen, Z.F.; Liu, P.Y.; Kuo, C.C.; Chuang, Y.S.; Lu, M.Z.; Kuo, M.C.; Chiu, Y.W.; Lin, Y.T. Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Indole Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.H.; Tseng, Y.F.; Liu, W.; Chuang, Y.S.; Tai, C.J.; Tung, C.W.; Lai, K.Y.; Kuo, M.C.; Chiu, Y.W.; Hwang, S.J.; et al. Exploring the Relationship between Gut Microbiome Composition and Blood Indole-3-acetic Acid in Hemodialysis Patients. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Plummer, N.T. Part 1: The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. Integr. Med. 2014, 13, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, T.E.; Morton, J.M. The human gut microbiome: A review of the effect of obesity and surgically induced weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, F. A cross-sectional study on gut microbiota in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing kidney transplant or hemodialysis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 1756–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.; Zhao, W.; Lin, Z.; Wu, J.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, J.; Peng, H. The Effects of Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis on the Gut Microbiota of End-Stage Renal Disease Patients, and the Relationship Between Gut Microbiota and Patient Prognoses. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 579386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zeng, R. Gut Dysbiosis and Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 829349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncir, T. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis: Triggers, Consequences, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Options. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Wu, P.-H.; Lin, Y.-T.; Hung, S.-C. Gut dysbiosis and mortality in hemodialysis patients. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Chen, D.-Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.-R.; Vaziri, N.D.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Microbiome–metabolome reveals the contribution of gut–kidney axis on kidney disease. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, S.; Alden, N.; Lee, K. Pathways and functions of gut microbiota metabolism impacting host physiology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015, 36, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Clément, K.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021, 70, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.; Zadeh, K.; Vekariya, R.; Ge, Y.; Mohamadzadeh, M. Tryptophan Metabolism and Gut-Brain Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Bose, C.; Mande, S.S. Tryptophan Metabolism by Gut Microbiome and Gut-Brain-Axis: An in silico Analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamalan, O.A.; Moore, M.J.; Al Khalili, Y. Physiology, Serotonin. In StatPearls; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Iesanu, M.I.; Zahiu, C.D.M.; Dogaru, I.A.; Chitimus, D.M.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Isac, S.; Galos, F.; Pavel, B.; O’Mahony, S.M.; et al. Melatonin-Microbiome Two-Sided Interaction in Dysbiosis-Associated Conditions. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, C.; Beresford, I.; Fraser, N.; Giles, H. Pharmacological characterization of human recombinant melatonin mt(1) and MT(2) receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 129, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.T.; Tseng, Y.H.; Jui, H.Y.; Kuo, C.C.; Wu, K.K.; Lee, C.M. 5-Methoxytryptophan attenuates postinfarct cardiac injury by controlling oxidative stress and immune activation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2021, 158, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Liu, B.; Zheng, H. 225-OR: 5-Methoxytryptamine Improves Obesity-Related Inflammation and Insulin Resistance by Regulating M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization. Diabetes 2022, 71 (Suppl. S1), 225-OR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.M.; Yu, K.; Donaldson, G.P.; Shastri, G.G.; Ann, P.; Ma, L.; Nagler, C.R.; Ismagilov, R.F.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Hsiao, E.Y. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015, 161, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonmatí-Carrión, M.; Rol, M.A. Melatonin as a Mediator of the Gut Microbiota-Host Interaction: Implications for Health and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ran, L.; Wu, Y.; Liang, M.; Zeng, J.; Ke, F.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Lao, X.; Liu, L.; et al. Oral Administration of 5-Hydroxytryptophan Restores Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in a Mouse Model of Depression. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 864571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waclawiková, B.; Bullock, A.; Schwalbe, M.; Aranzamendi, C.; Nelemans, S.A.; van Dijk, G.; El Aidy, S. Gut bacteria-derived 5-hydroxyindole is a potent stimulant of intestinal motility via its action on L-type calcium channels. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birdsall, T.C. 5-Hydroxytryptophan: A clinically-effective serotonin precursor. Altern. Med. Rev. 1998, 3, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacki, C.; Popławski, T.; Błońska, A.; Błasiak, J.; Romanowski, M.; Chojnacki, J. Expression of tryptophan hydroxylase in gastric mucosa in symptomatic and asymptomatic Helicobacter pylori infection. Arch. Med. Sci. 2019, 15, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.D.; Woting, A.; Jaenicke, T.; Sander, A.; Sabrowski, W.; Rolle-Kampcyk, U.; von Bergen, M.; Blaut, M. Clostridium ramosum regulates enterochromaffin cell development and serotonin release. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandouzi, Z.A.; Lee, J.; Del Carmen Rosas, M.; Chen, J.; Henderson, W.A.; Starkweather, A.R.; Cong, X.S. Associations of neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome with emotional distress in mixed type of irritable bowel syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.H.; Ho, Y.C.; Ho, H.H.; Liang, L.Y.; Jiang, W.C.; Lee, G.L.; Lee, J.K.; Hsu, Y.J.; Kuo, C.C.; Wu, K.K.; et al. Tryptophan metabolite 5-methoxytryptophan ameliorates arterial denudation-induced intimal hyperplasia via opposing effects on vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Aging 2019, 11, 8604–8622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Lin, Y.H.; Tang, S.G.; Zhu, Y.M. 5-methoxytryptophan alleviates liver fibrosis by modulating FOXO3a/miR-21/ATG5 signaling pathway mediated autophagy. Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Wei, F.; Hu, J. The effects of Qingchang Ligan formula on hepatic encephalopathy in mouse model: Results from gut microbiome-metabolomics analysis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1381209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gong, L.; Liu, F.; Ren, Y.; Mu, J. Alteration of Gut Microbiome and Correlated Lipid Metabolism in Post-Stroke Depression. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 663967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, A.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Seixas, A.; Girardin, J.L.; McFarlane, S.I. Melatonin, the Hormone of Darkness: From Sleep Promotion to Ebola Treatment. Brain Disord. Ther. 2014, 4, 1000151. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y. Melatonin attenuates microbiota dysbiosis of jejunum in short-term sleep deprived mice. J. Microbiol. 2020, 58, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Wu, H.; Huang, X.; Yu, T. Melatonin, a natural antioxidant therapy in spinal cord injury. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1218553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhou, C.; Kurogi, K.; Sakakibara, Y.; Suiko, M.; Liu, M.C. Sulfation of 6-hydroxymelatonin, N-acetylserotonin and 4-hydroxyramelteon by the human cytosolic sulfotransferases (SULTs). Xenobiotica 2016, 46, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Diduk, R.; Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. N-Acetylserotonin and 6-Hydroxymelatonin against Oxidative Stress: Implications for the Overall Protection Exerted by Melatonin. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 8535–8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Spengler, K.; Terberger, K.; Boehm, M.; Appel, J.; Barske, T.; Timm, S.; Battchikova, N.; Hagemann, M.; et al. Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase and low abundant ferredoxins support aerobic photomixotrophic growth in cyanobacteria. eLife 2022, 11, e71339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, D.M.M.; Szymczak, S.; Schuchardt, S.; Labrenz, J.; Tran, F.; Welz, L.; Graßhoff, H.; Zirpel, H.; Sümbül, M.; Oumari, M.; et al. Tryptophan degradation as a systems phenomenon in inflammatio–an analysis across 13 chronic inflammatory diseases. eBioMedicine 2024, 102, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Modulation of immunity by tryptophan microbial metabolites. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1209613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ling, Y.; Peng, Y.; Han, S.; Ren, Y.; Jing, Y.; Fan, W.; Su, Y.; Mu, C.; Zhu, W. Regulation of serotonin production by specific microbes from piglet gut. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tang, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zan, L. Melatonin promotes triacylglycerol accumulation via MT2 receptor during differentiation in bovine intramuscular preadipocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, N.T.; Irber, L.; Reiter, T.; Brooks, P.; Brown, C.T. Large-scale sequence comparisons with sourmash. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Steinegger, M.; Breitwieser, F.; Söding, J.; Levy Karin, E. Fast and sensitive taxonomic assignment to metagenomic contigs. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 3029–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Doak, T.G. A parsimony approach to biological pathway reconstruction/inference for genomes and metagenomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, R.; Billington, R.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; Midford, P.E.; Ong, W.K.; Paley, S.; Subhraveti, P.; Karp, P.D. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes-a 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D445–D453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, G.P.; Kin, K.; Lynch, V.J. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory Biosci. 2012, 131, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Li, F.; Kirton, E.; Thomas, A.; Egan, R.; An, H.; Wang, Z. MetaBAT 2: An adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirana, I.; Vila, J.; Sanz, H. Comparegroups 4.0: Descriptives by Groups. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/compareGroups/vignettes/compareGroups_vignette.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Isaac Subirana, J.S. Descriptive Analysis by Groups. R package version 4.6.0. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=compareGroups (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-4. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Navarro, D.; Lin Pedersen, T. Data analysis. In ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data AnalysisI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, Q.; Wang, D.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Niu, C. microbiomeMarker: An R/Bioconductor package for microbiome marker identification and visualization. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4027–4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters/Groups N (%) or Mean (SD) or Median [Q1; Q3] | 5-HTP (nM) | p | Serotonin (nM) | p | 5-MTP (nM) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (N = 42) | Low (N = 43) | High (N = 42) | Low (N = 43) | High (N = 42) | Low (N = 43) | ||||

| Age | 60.2 (10.3) | 60.8 (11.2) | 0.783 | 58.2 (10.1) | 62.7 (11.0) | 0.052 | 58.3 (10.7) | 62.7 (10.5) | 0.064 |

| Female | 20 (47.6%) | 16 (37.2%) | 0.452 | 17 (40.5%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.899 | 16 (38.1%) | 20 (46.5%) | 0.572 |

| DM | 10 (23.8%) | 18 (41.9%) | 0.124 | 14 (33.3%) | 14 (32.6%) | 1.000 | 13 (31.0%) | 15 (34.9%) | 0.877 |

| HTN | 29 (69.0%) | 38 (88.4%) | 0.056 | 32 (76.2%) | 35 (81.4%) | 0.748 | 30 (71.4%) | 37 (86.0%) | 0.166 |

| CAD | 7 (16.7%) | 11 (25.6%) | 0.459 | 5 (11.9%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.072 | 9 (21.4%) | 9 (20.9%) | 1.000 |

| PPI use | 11 (26.2%) | 2 (4.65%) | 0.014 | 9 (21.4%) | 4 (9.30%) | 0.211 | 7 (16.7%) | 6 (14.0%) | 0.963 |

| Albumin | 3.91 (0.36) | 3.91 (0.35) | 0.931 | 3.89 (0.35) | 3.93 (0.36) | 0.526 | 3.91 (0.33) | 3.92 (0.38) | 0.897 |

| Kt/V (D) | 1.56 (0.19) | 1.51 (0.22) | 0.246 | 1.54 (0.22) | 1.53 (0.20) | 0.949 | 1.51 (0.18) | 1.56 (0.23) | 0.231 |

| hs-CRP | 3.87 (4.47) | 5.09 (6.93) | 0.340 | 3.81 (4.54) | 5.17 (6.92) | 0.291 | 4.35 (4.96) | 4.62 (6.66) | 0.835 |

| Hemodialysis Vintage | 111 (74.4) | 72.7 (65.5) | 0.014 | 75.4 (60.3) | 107 (79.8) | 0.041 | 97.9 (71.7) | 85.3 (73.1) | 0.425 |

| Metabolites (nM) | 2.74 [2.04; 6.65] | 0.03 [0.00; 0.45] | <0.001 | 13.5 [10.7; 21.2] | 6.36 [2.87; 27.2] | <0.001 | 21.8 [18.4; 27.1] | 12.2 [9.54; 14.3] | <0.001 |

| Parameters/Groups N (%) or Mean (SD) or Median [Q1; Q3] | 5-Methoxytryptamine (nM) | p | Melatonin (nM) | p | 6-Hydroxymelatonin (nM) | p | |||

| High (N = 40) | Low (N = 45) | High (N = 42) | Low (N = 43) | High (N = 42) | Low (N = 43) | ||||

| Age | 57.3 (11.5) | 63.4 (9.21) | 0.010 | 59.5 (9.72) | 61.5 (11.7) | 0.413 | 61.3 (11.6) | 59.7 (9.90) | 0.506 |

| Female | 18 (45.0%) | 18 (40.0%) | 0.806 | 16 (38.1%) | 20 (46.5%) | 0.572 | 17 (40.5%) | 19 (44.2%) | 0.899 |

| DM | 14 (35.0%) | 14 (31.1%) | 0.881 | 12 (28.6%) | 16 (37.2%) | 0.538 | 15 (35.7%) | 13 (30.2%) | 0.759 |

| HTN | 33 (82.5%) | 34 (75.6%) | 0.606 | 31 (73.8%) | 36 (83.7%) | 0.394 | 32 (76.2%) | 35 (81.4%) | 0.748 |

| CAD | 8 (20.0%) | 10 (22.2%) | 1.000 | 8 (19.0%) | 10 (23.3%) | 0.834 | 7 (16.7%) | 11 (25.6%) | 0.459 |

| PPI use | 5 (12.5%) | 8 (17.8%) | 0.709 | 7 (16.7%) | 6 (14.0%) | 0.963 | 8 (19.0%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0.516 |

| Albumin | 3.91 (0.36) | 3.92 (0.42) | 0.710 | 3.95 (0.30) | 3.87 (0.40) | 0.263 | 3.89 (0.38) | 3.93 (0.32) | 0.544 |

| Kt/V (D) | 1.56 (0.19) | 1.54 (0.21) | 0.873 | 1.54 (0.21) | 1.53 (0.21) | 0.899 | 1.53 (0.21) | 1.54 (0.21) | 0.698 |

| hs-CRP | 3.87 (4.47) | 4.36 (5.83) | 0.825 | 4.70 (6.08) | 4.29 (5.70) | 0.754 | 4.54 (6.42) | 4.45 (5.34) | 0.944 |

| Hemodialysis Vintage | 111 (74.4) | 84.0 (67.3) | 0.314 | 94.9 (69.9) | 88.3 (75.2) | 0.675 | 97.8 (78.7) | 85.4 (65.7) | 0.433 |

| Metabolites (nM) | 2.74 [2.04; 6.65] | 0.90 [0.69; 1.02] | <0.001 | 0.69 [0.60; 1.73] | 0.12 [0.06; 0.27] | <0.001 | 6.15 [4.79; 13.0] | 2.22 [1.65; 2.91] | <0.001 |

| Metabolites/MGS | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Values | Adjusted p-Values | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HTP (nM) | 0.346 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | 1.30 | (0.27, 2.32) | 0.014 * | 0.069 • | |

| Anaerotignum lactatifermentans | 0.49 | (0.00, 0.98) | 0.048 * | 0.160 | |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis | 0.48 | (0.19, 0.78) | 0.002 ** | 0.016 * | |

| Bacteroides finegoldii CAG:203 | −0.62 | (−1.32, 0.08) | 0.080 • | 0.172 | |

| Down-Regulate | |||||

| Sutterella sp. KLE1602 | 0.05 | (−0.22, 0.33) | 0.704 | 0.704 | |

| Roseburia faecis | −0.19 | (−0.60, 0.22) | 0.349 | 0.436 | |

| Roseburia hominis | −0.24 | (−0.58, 0.10) | 0.169 | 0.282 | |

| Ruminococcaceae bacterium AF10-16 | −0.10 | (−0.49, 0.29) | 0.602 | 0.669 | |

| Sutterella sp. | −0.21 | (−0.58, 0.16) | 0.267 | 0.382 | |

| Serotonin (nM) | 0.445 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | −5.47 | (−38.85, 27.91) | 0.745 | 0.767 | |

| Bacteroides finegoldii | 10.19 | (−9.49, 29.87) | 0.305 | 0.663 | |

| Bacteroides stercoris CAG:120 | 11.21 | (−6.27, 28.69) | 0.205 | 0.663 | |

| Bacteroides neonati | −7.62 | (−28.87, 13.64) | 0.477 | 0.735 | |

| Parabacteroides johnsonii CAG:246 | −6.77 | (−20.80, 7.26) | 0.339 | 0.663 | |

| Bacteroides sp. CAG:633 | 4.96 | (−14.65, 24.57) | 0.616 | 0.767 | |

| Bacteroides sp. AM16-15 | 5.10 | (−3.49, 13.68) | 0.241 | 0.663 | |

| Helicobacter felis | 24.82 | (14.18, 35.50) | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Bacteroides sp. HPS0048 | 1.95 | (−11.10, 15.00) | 0.767 | 0.767 | |

| Bacteroides congonensis | 1.72 | (−7.76, 11.20) | 0.719 | 0.767 | |

| Bacteroides fragilis CAG:558 | 4.98 | (−10.28, 20.23) | 0.517 | 0.735 | |

| Down-Regulate | |||||

| Clostridium symbiosum | −4.53 | (−19.14, 10.09) | 0.539 | 0.735 | |

| Rhizobium sp. ASV8 | −11.46 | (−24.17, 1.26) | 0.077 • | 0.383 | |

| Eubacterium sp. CAG:180 | −12.90 | (−23.50, −2.29) | 0.018 * | 0.134 | |

| 5-MTP (nM) | 0.255 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Oscillibacter sp. | 0.84 | (−0.41, 2.09) | 0.186 | 0.464 | |

| Roseburia intestinalis | −0.42 | (−1.77, 0.94) | 0.543 | 0.991 | |

| Eubacterium rectale | 0.15 | (−1.36, 1.66) | 0.846 | 0.991 | |

| Barnesiella intestinihominis | 0.00 | (−0.58, 0.58) | 0.991 | 0.991 | |

| Ruminococcus bromii | 0.17 | (−0.76, 1.10) | 0.716 | 0.991 | |

| Ruminococcaceae bacterium TF06-43 | 0.07 | (−1.12, 1.25) | 0.912 | 0.991 | |

| Ruminococcus sp. | 0.98 | (−0.03, 1.98) | 0.056 • | 0.187 | |

| Down-Regulate | |||||

| Bacteroides ovatus | −2.91 | (−5.13, −0.69) | 0.011 * | 0.054 • | |

| Ruminococcus gnavus | −0.02 | (−1.14, 1.11) | 0.978 | 0.991 | |

| 5-Methoxytryptamine (nM) | 0.102 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Prevotella copri | 0.10 | (−0.10, 0.29) | 0.332 | 0.665 | |

| Mailhella massiliensis | −0.04 | (−0.26, 0.16) | 0.668 | 0.842 | |

| Prevotella sp. CAG:279 | 0.03 | (−0.17, 0.24) | 0.748 | 0.842 | |

| Prevotella lascolaii | 0.15 | (−0.10, 0.41) | 0.232 | 0.626 | |

| Clostridium sp. AM33-3 | 0.14 | (−0.07, 0.35) | 0.184 | 0.626 | |

| Sutterella sp. | 0.02 | (−0.18, 0.21) | 0.842 | 0.842 | |

| Down-Regulate | |||||

| Parabacteroides johnsonii CAG:246 | −0.06 | (−0.29, 0.18) | 0.634 | 0.842 | |

| Melatonin (nM) | 0.195 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Clostridium sp. AT4 | 0.22 | (0.03, 0.40) | 0.021 * | 0.052 | |

| Phascolarctobacterium faecium | −0.28 | (−0.46, −0.11) | 0.002 ** | 0.010 * | |

| Bacteroides sp. 519 | 0.05 | (−0.26, 0.37) | 0.728 | 0.728 | |

| Clostridium sp. 27_14 | 0.22 | (−0.00, 0.45) | 0.053 • | 0.088 • | |

| 6-Hydroxymelatonin (nM) | 0.096 | ||||

| Up-Regulate | |||||

| Flavonifractor plautii | −0.74 | (−4.10, 2.63) | 0.664 | 0.885 | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | 0.58 | (−0.43, 1.59) | 0.255 | 0.885 | |

| Muribaculaceae bacterium | 0.58 | (−1.150, 2.31) | 0.507 | 0.885 | |

| Clostridium symbiosum | 1.43 | (−0.47, 3.34) | 0.139 | 0.885 | |

| Blautia sp. CAG:257 | 0.96 | (−1.00, 2.91) | 0.333 | 0.885 | |

| Down-Regulate | |||||

| Bacteroides neonati | −0.55 | (−2.88, 1.78) | 0.640 | 0.885 | |

| Bacteroides sp. CAG:875 | 0.30 | (−1.85, 2.44) | 0.783 | 0.895 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuo, T.-H.; Wu, P.-H.; Liu, P.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-S.; Tai, C.-J.; Kuo, M.-C.; Chiu, Y.-W.; Lin, Y.-T. Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Serotonin Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110463

Kuo T-H, Wu P-H, Liu P-Y, Chuang Y-S, Tai C-J, Kuo M-C, Chiu Y-W, Lin Y-T. Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Serotonin Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110463

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuo, Tien-Hsiang, Ping-Hsun Wu, Po-Yu Liu, Yun-Shiuan Chuang, Chi-Jung Tai, Mei-Chuan Kuo, Yi-Wen Chiu, and Yi-Ting Lin. 2025. "Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Serotonin Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110463

APA StyleKuo, T.-H., Wu, P.-H., Liu, P.-Y., Chuang, Y.-S., Tai, C.-J., Kuo, M.-C., Chiu, Y.-W., & Lin, Y.-T. (2025). Identification of Gut Microbiome Signatures Associated with Serotonin Pathway in Tryptophan Metabolism of Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110463