Assessment of Potential Factors Influencing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Drug Adherence: A Database Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

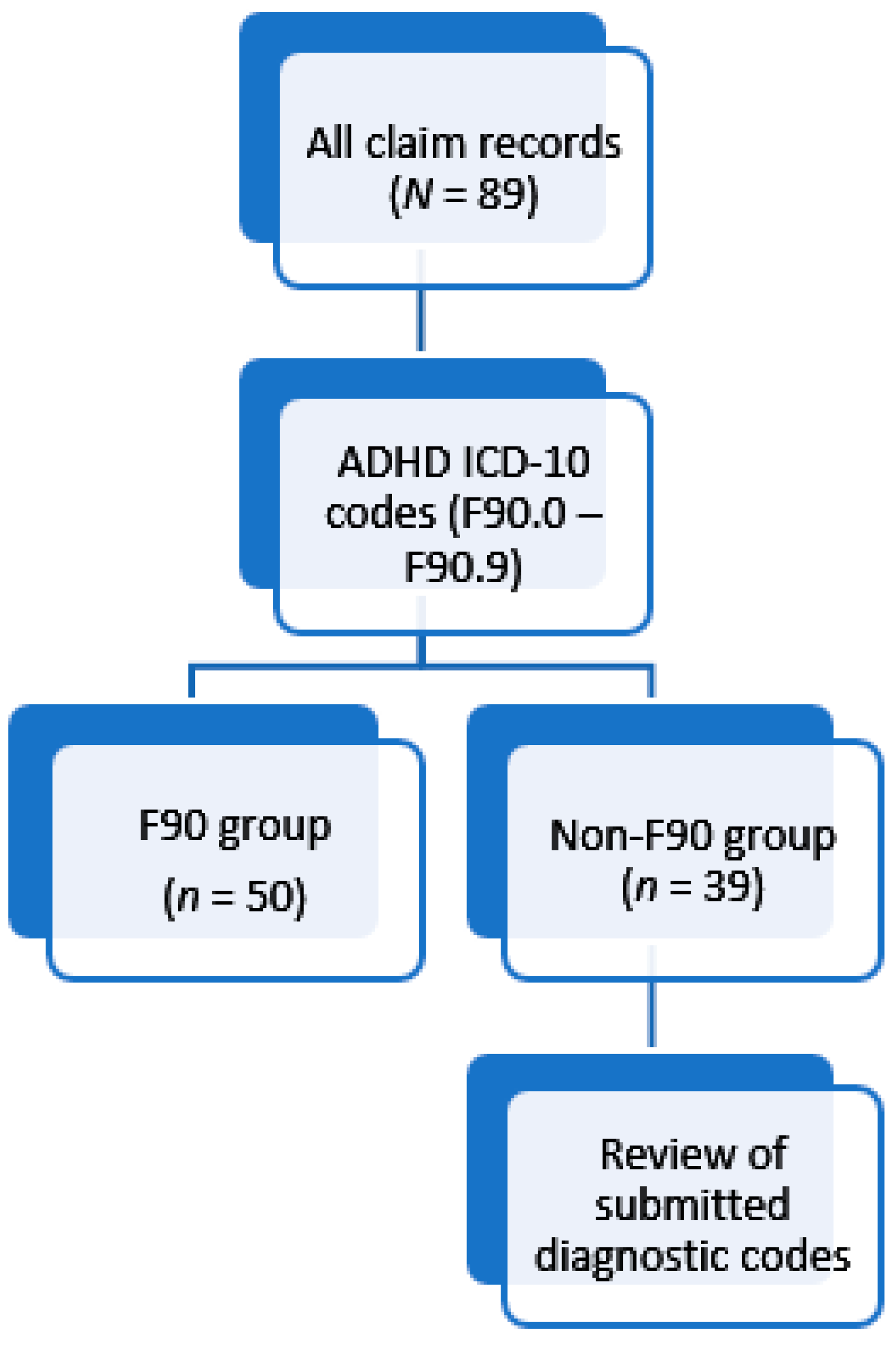

- Identify patients with confirmed ADHD diagnoses versus those prescribed stimulants under other diagnostic codes;

- Compare whether differences in medicine adherence are noted between diagnostic groups;

- Compare whether adherence to methylphenidate therapy is modified by antidepressant use.

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Monthly medicine plotting

- Receiving 12 or more monthly issues of either drug type over the five-year period.

- Receiving a minimum of seven monthly issues within 12 months.

- (ii)

- Proportion of days covered

3. Results

4. Discussion

- The claims included in the dataset were only representative of those submitted to the included medical aids’ administration for consideration. It is possible that subjects may have paid privately for their medication, thus possibly confounding adherence measurements.

- ICD codes were not available for 2012 and few were indicated for 2013. Thus, identification of the F90 group may have omitted members who were assigned to the Non-F90 group based on the lack of an appropriate diagnostic code.

- The field indicating the number of days supply was only available for claims in 2016. These were not applied in the analysis for the purpose of consistency in assessment method and due to noted inaccuracies in the supply duration provided.

- Dosage instructions for the medicines were not available.

- Consumption of medication was based on dispensing records; it was not possible to determine if medication was taken as prescribed.

- There was no control for psychological comorbidities other than depression, experience with medication, or treatment preferences.

- Lastly, the small sample size impacted on generalizability and margins of error.

- Other potential confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status, healthcare access, and variations in prescribing practices that could influence adherence rates, were not considered in this study.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. National Clinical Practice Guideline Number 72—Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults; The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, K.M. Neuropsychiatric Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder that responds to ADHD medication (NADHDM) in the International Classification of Diseases ICD-11: An opportunity to increase sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis. IJHSSE 2014, 1, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gaebel, W.; Zielasek, J.; Reed, G.M. Mental and behavioural disorders in the ICD-11: Concepts, methodologies, and current status. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajria, K.; Lu, M.; Sikirica, V.; Greven, P.; Zhong, Y.; Qin, P.; Xie, J. Adherence, persistence, and medication discontinuation in patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder—A systematic literature review. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1543–1569. [Google Scholar]

- Semerci, Z.B. Resistance and resolutions in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Klinik. Psikofarmakol. Bülteni. 2013, 23, S53–S54. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, D. (Ed.) South African Medicines Formulary (SAMF), 12th ed.; Health and Medical Publishing Group: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016; p. 650. [Google Scholar]

- Schellack, N.; Meyer, H. The management of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in children. S. Afr. Pharm. J. 2012, 79, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo, M.R. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J.; Barber, N.; Elliott, R.A.; Morgan, M. Concordance, Adherence and Compliance in Medicine Taking; NCCSDO: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, R.; Weinman, J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 1999, 47, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolnierek, K.B.H.; DiMatteo, M.R. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: A meta-analysis. Med. Care 2009, 47, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.K. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterberg, L.; Blaschke, T. Adherence to medication. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, H.; Brissette, I.; Leventhal, E.A. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour; Cameron, L.D., Leventhal, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, K.J.; Weinman, J. Patients’ perceptions of their illness: The dynamo of volition in health care. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumyn, L.; French, L.; Hechtman, L. Comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobanski, E. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, C.H.; Bobo, W.; Warner, C.; Reid, S.; Rachal, J. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Am. Fam. Physician 2006, 74, 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Howland, R.H. Medication holidays. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Men. 2009, 47, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Vogt, C.; Donyai, P. Caught in the eye of the storm: A qualitative study of views and experiences of planned drug holidays from methylphenidate in child and adolescent ADHD treatment. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 21, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyzoi, M.; Ahnemark, E.; Medin, E.; Ginsberg, Y. Estimated prevalence and incidence of diagnosed ADHD and health care utilization in adults in Sweden—A longitudinal population-based register study. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.A.; Roy, A.; Burrell, A.; Fairchild, C.J.; Fuldeore, M.J.; Ollendorf, D.A.; Wong, P.K. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008, 11, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; Wiley-Exley, E.K.; Richards, S.; Domino, M.E.; Carey, T.S.; Sleath, B.L. Contrasting measures of adherence with simple drug use, medication switching, and therapeutic duplication. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raebel, M.A.; Schmittdiel, J.; Karter, A.J.; Konieczny, J.L.; Steiner, J.F. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med. Care 2013, 51, S11–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyman, J.R. (Ed.) Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS); MIMS: Saxonwold, South Africa, 2016; Volume 56, 405p. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, J.A.; Rosenheck, R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr. Serv. 1998, 49, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleppe, M.; Lacroix, J.; Ham, J.; Midden, C. ‘A necessary evil’: Associations with taking medication and their relationship with medication adherence. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emilsson, M.; Gustafsson, P.A.; Öhnström, G.; Marteinsdottir, I. Beliefs regarding medication and side effects influence treatment adherence in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciraulo, D.A.; Shader, R.I.; Greenblatt, D.J. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics of antidepressants. In Pharmacotherapy of Depression; Ciraulo, D.A., Shader, R.I., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 33–124. [Google Scholar]

- Safren, S.A.; Duran, P.; Yovel, I.; Perlman, C.A.; Sprich, S. Medication adherence in psychopharmacologically treated adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2007, 10, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicines Related Substances Act 101 of 1965, Section 22A. 6(g, i); Government Gazette: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- Geffen, J.; Forster, K. Treatment of adult ADHD: A clinical perspective. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 8, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnia, M.; Pirzadeh, A.; Nazari, A.; Heidari, Z. Applications for the management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A systematic review. Front. Public. Health 2025, 13, 1483923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rule Number | Explanation of Rule |

|---|---|

| Rule 1 | The number of days between antidepressant/ADHD medication issues was equal to 21 or more days, and either the preceding or proceeding month did not contain records of an issue misaligned with an otherwise stable pattern of usage for the same drug or drug class, strength, and quantity dispensed. |

| Rule 2 | A regular trend for drug and dosage was observed with minimal outliers, and the total days between dispensing points were calculated against the total units dispensed and compared to determine if these matched the approximate daily dosage as per the regular trend observed. |

| Assessment Period | Circumstance | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 90 days | Standard applied duration, unless a requirement to adjust upwards or downwards was indicated by actual dispensing dates. | Not applicable. |

| Over 90 days | The end date of the total number of days covered for two or three consecutive issues of medicine exceeded the 90-day cut-off and/or the number of days between the end date and the date of the next issue of medicine exceeded 90 days. | First issue: 16 January 2014 Second issue: 18 February 2014 Third issue: 20 March 2014 Fourth issue: 23 April 2014 Total: 97 days between the first issue and the date of THE fourth issue. The date of THE fourth issue calculated from THE third issue would be 19 April 2014. |

| Up to 119 days | Medicine noted as having been dispensed shortly before the 90-day cut-off as a result of delays between consecutive issues which exceeded the number of days which were covered, and/or no further issue of medicine was carried out in the preceding month, and the calculated end date of the final issue fell within this range. | First issue: 3 August 2014 Next issue: 30 October 2014 Calculated proceeding supply date: 29 November 2014 Total: 118 days |

| 120–129 days | The last issue of medicine falls appropriately within the approximate 90-day period, but the next issue date of the medicine, which would indicate the assessment end date, differs by over 119 days but less than 130 days, and the usage pattern is regular. | First issue: 28 Apr 2015 Second issue: 3 June 2015 Third issue: 3 July 2015 Fourth issue: 31 August 2015 Total: 125 days; the next supply date after 3 July 2015 would be 2 August 2015, representing a total of 96 days, but the actual date for consecutive issuing of the same medicine was slightly later. |

| Less than 90 days | If one month within an assessment period of 90 days had no issue, however the number of days covered within the next assessment period was equal to or greater than 60, with its first issue date being slightly before the end of the first assessment period (approximately 90 days), the assessment period was closed as of the date of the first issue of medicine within the next assessment period and could represent less than 90 days. | First issue: 25 February 2013 Second issue: 13 April 2013 Third issue: 18 May 2013 Fourth issue: 27 June 2013 Fifth issue: 17 August 2014 Total: 82 days between the first issue and the third issue. The next assessment period has 60 days of coverage over a 91-day period. |

| End date for database records | Medicine issues at the end of 2016 were calculated against the number of days that would have passed up until 1 Jan 2017, as the absence of a proceeding issue date leaves the assessment for the days covered indeterminate. | First issue: 2 November 2016 Second issue: 5 December 2016 End date: 1 January 2017 Total: 60 days, with confirmed coverage of 57 days within the period. |

| Patient Group | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F90 (n) | 34 | 38 | 41 | 50 | 45 | 50 |

| Age range | 18.24–36.51 | 19.24–37.51 | 20.24–38.51 | 20.63–39.51 | 21.63–39.56 | - |

| Average age | 25.45 ± 6.13 | 26.6 ± 6.10 | 27.57 ± 5.94 | 28.19 ± 5.68 | 29.01 ± 5.63 | - |

| Female (n) | 20 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 23 |

| Age range | 18.24–36.51 | 19.24–37.51 | 20.24–38.51 | 20.63–39.51 | 21.63–39.56 | - |

| Average age | 25.74 ± 6.23 | 26.74 ± 6.07 | 27.3 ± 6.13 | 27.97 ± 6.2 | 28.59 ± 5.9 | - |

| Male (n) | 14 | 18 | 19 | 27 | 24 | 27 |

| Age range | 18.30–35.01 | 19.30–36.13 | 20.30–37.13 | 21.30–38.13 | 22.30–39.13 | - |

| Average age | 25.03 ± 6.19 | 26.44 ± 6.31 | 27.88 ± 5.87 | 28.38 ± 5.31 | 29.39 ± 5.47 | - |

| Non–F90 (n) | 23 | 29 | 32 | 39 | 36 | 39 |

| Age range | 18.57–35.26 | 19.57–36.26 | 20.57–37.26 | 21.57–39.47 | 22.57–40.47 | - |

| Average age | 27.17 ± 5.52 | 28.54 ± 5.39 | 29.01 ± 5.47 | 30.07 ± 5.41 | 30.84 ± 5.33 | - |

| Female (n) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 17 | 19 |

| Age range | 18.57–35.26 | 19.57–36.26 | 20.57–37.26 | 21.57–38.26 | 22.57–39.26 | - |

| Average age | 26.17 ± 5.95 | 26.74 ± 5.7 | 27.36 ± 5.6 | 28.32 ± 5.44 | 29 ± 5.29 | - |

| Male (n) | 9 | 13 | 14 | 20 | 19 | 20 |

| Age range | 19.47–35.17 | 20.47–36.17 | 21.47–37.17 | 22.32–39.47 | 23.32–40.47 | - |

| Average age | 28.72 ± 4.68 | 30.76 ± 4.19 | 31.12 ± 4.67 | 31.74 ± 4.94 | 32.48 ± 4.93 | - |

| MPH & AD | MPH Alone | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Use | Irregular Use | Regular Use | Irregular Use | Regular Use | Irregular Use | |||||||||||||

| N | % | PDC | N | % | PDC | N | % | PDC | N | % | PDC | % | PDC | % | PDC | |||

| AD | MPH | AD | MPH | |||||||||||||||

| F90 (n = 50) | 16 | 32.00 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 4 | 8.00 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 8 | 16.00 | 0.73 | 22 | 44.00 | 0.48 | 48.00 | 0.69 | 52.00 | 0.50 |

| Female (n = 50) | 11 | 22.00 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 1 | 2.00 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 2 | 4.00 | 0.73 | 9 | 18.00 | 0.49 | 26.00 | 0.71 | 20.00 | 0.49 |

| % of females in group (n = 23) | - | 47.83 | - | - | - | 4.35 | - | - | - | 8.70 | - | - | 39.13 | - | 56.52 | - | 43.48 | - |

| % of females in group on antidepressants (n = 12) | - | 91.67 | - | - | - | 8.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | - | - | - | - | - |

| Male (n = 50) | 5 | 10.00 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 3 | 6.00 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 6 | 12.00 | 0.73 | 13 | 26.00 | 0.47 | 22.00 | 0.67 | 32.00 | 0.51 |

| % of males in group (n = 27) | - | 18.52 | - | - | - | 11.11 | - | - | - | 22.22 | - | - | 48.15 | - | 40.74 | - | 59.26 | - |

| % of males in group on antidepressants (n = 8) | - | 62.50 | - | - | - | 37.50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | – | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non–F90 (n = 39) | 7 | 17.95 | 0.87 | 0.43 | 6 | 15.38 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 1 | 2.56 | 0.71 | 25 | 64.10 | 0.38 | 20.51 | 0.65 | 79.48 | 0.43 |

| Female (n = 39) | 1 | 2.56 | 0.92 | 0.11 | 3 | 7.69 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 1 | 2.56 | 0.71 | 14 | 35.90 | 0.38 | 5.12 | 0.58 | 43.59 | 0.41 |

| % of females in group (n = 19) | - | 5.26 | - | - | - | 15.79 | - | - | - | 5.26 | – | – | 73.68 | – | 10.53 | - | 89.47 | - |

| % of females in group on antidepressants (n = 4) | - | 25.00 | - | - | - | 75.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Male (n = 39) | 6 | 15.38 | 0.86 | 0.48 | 3 | 7.69 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.00 | - | 11 | 28.21 | 0.38 | 15.38 | 0.67 | 35.90 | 0.45 |

| % of males in group (n = 20) | - | 30.00 | - | - | - | 15.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 55.00 | - | 45.00 | - | 55.00 | - |

| % of males in group on antidepressants (n = 9) | - | 66.67 | - | - | - | 33.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Antidepressant Portion | PDC | Methylphenidate Portion | PDC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All regular use (N = 23) | 62.44% | 0.77 | 37.56% | 0.58 |

| Female (n = 12) | 62.79% | 0.78 | 37.21% | 0.60 |

| Male (n = 11) | 67.23% | 0.76 | 32.77% | 0.54 |

| F90 regular (n = 16) | 56.72% | 0.73 | 43.28% | 0.64 |

| Female (n = 11) | 59.70% | 0.77 | 40.30% | 0.65 |

| Male (n = 5) | 50.17% | 0.64 | 49.83% | 0.62 |

| Non-F90 regular (n = 7) | 83.64% | 0.87 | 16.36% | 0.43 |

| Female (n = 1) | 96.77% | 0.92 | 3.23% | 0.11 |

| Male (n = 6) | 81.45% | 0.86 | 18.55% | 0.48 |

| Concurrent AD | MPH Monotherapy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire study population (N = 89) | Overall | Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female |

| n = 56 | n = 30 | n = 26 | n = 33 | n = 16 | n = 17 | |

| Antidepressant PDC | 72.3% | 72.3% | 72.4% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Methylphenidate PDC | 55.0% | 54.5% | 55.6% | 47.4% | 48.8% | 45.9% |

| MPH PDD (mg) | 31.29 | 26.44 | 36.94 | 29.76 | 31.88 | 27.30 |

| F90 population (n = 50) | Overall | Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female |

| n = 20 | n = 8 | n = 12 | n = 30 | n = 19 | n = 11 | |

| Antidepressant PDC | 70.6% | 67.1% | 72.9% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Methylphenidate PDC | 62.6% | 59.2% | 64.9% | 54.5% | 55.3% | 53.3% |

| MPH PDD (mg) | 32.09 | 26.34 | 37.32 | 30.53 | 32.28 | 27.64 |

| Non–F90 population (n = 39) | Overall | Male | Female | Overall | Male | Female |

| n = 13 | n = 9 | n = 4 | n = 26 | n = 11 | n = 15 | |

| Antidepressant PDC | 76.3% | 78.8% | 70.8% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Methylphenidate PDC | 43.4% | 50.3% | 27.8% | 39.2% | 37.5% | 40.4% |

| MPH PDD (mg) | 26.50 | 26.75 | 24.10 | 27.39 | 29.06 | 26.75 |

| n | MPH PDC | PDD | N | MPH PDC | PDD | n | MPH PDC | PDD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | (mg) | Overall | (mg) | Overall | (mg) | ||||

| Entire Study Population | F90 Population | Non-F90 Population | |||||||

| Overall | 89 | 50.24% | 30.42 | 50 | 57.77% | 31.25 | 39 | 40.58% | 27.12 |

| Female | 42 | 49.57% | 31.46 | 23 | 59.33% | 32.91 | 19 | 37.76% | 26.61 |

| Male | 47 | 50.83% | 29.53 | 27 | 56.44% | 29.92 | 20 | 43.26% | 27.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truter, I.; Regnart, J.; Meyer, A. Assessment of Potential Factors Influencing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Drug Adherence: A Database Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050716

Truter I, Regnart J, Meyer A. Assessment of Potential Factors Influencing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Drug Adherence: A Database Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050716

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruter, Ilse, Judith Regnart, and Anneke Meyer. 2025. "Assessment of Potential Factors Influencing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Drug Adherence: A Database Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050716

APA StyleTruter, I., Regnart, J., & Meyer, A. (2025). Assessment of Potential Factors Influencing Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Drug Adherence: A Database Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050716