Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Quantitative Data Collection

Measurement Instruments

2.3.2. Qualitative Data

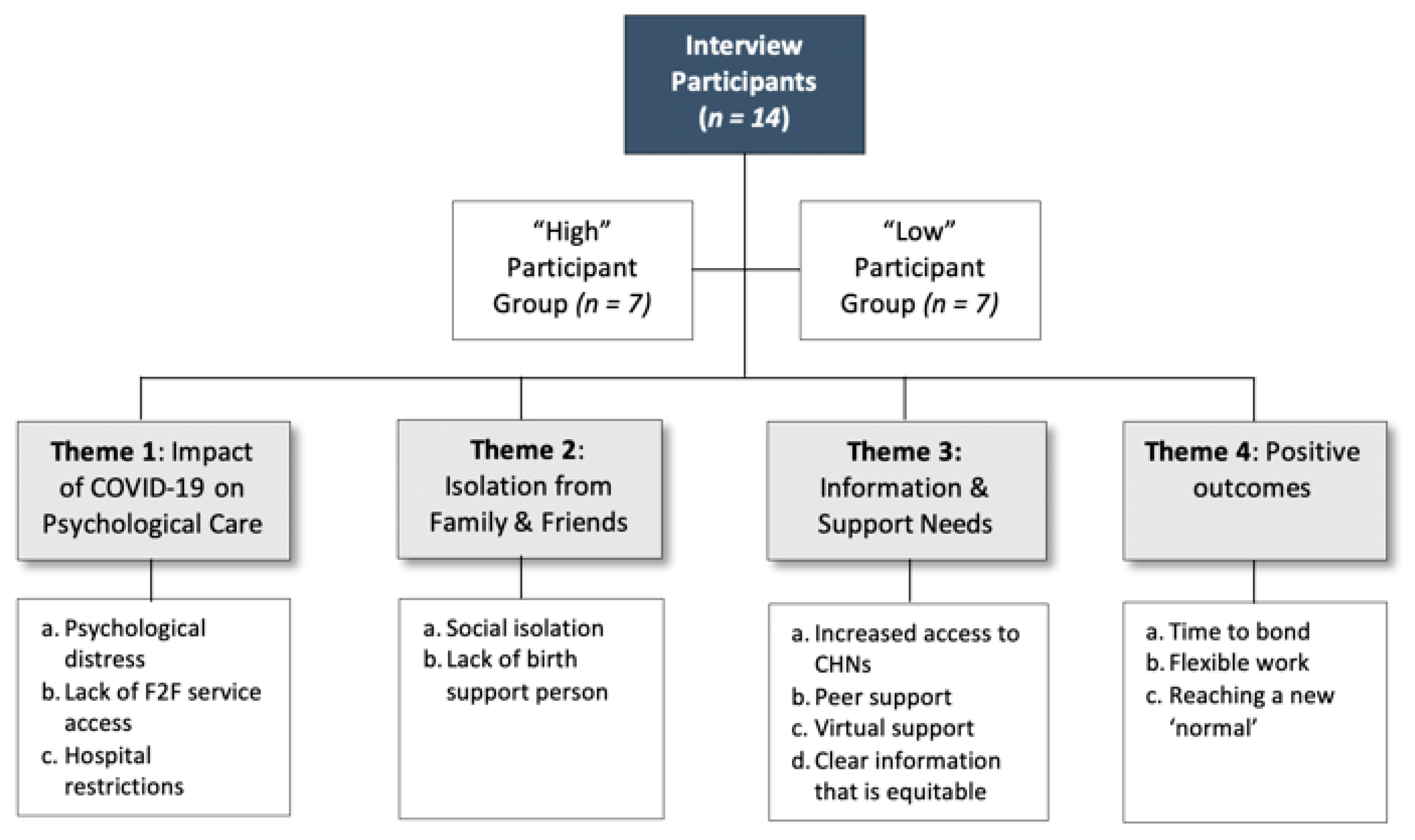

Stratification of Participants

Data Collection

- How, and if, COVID-19 had impacted emotional health and wellbeing during pregnancy.

- The type of emotional health and wellbeing information and services participants accessed.

- Emotional health and wellbeing needs during the last few months.

- Their views on how the wellbeing needs of pregnant women best be supported during times of crisis (such as a pandemic).

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Quantitative Data: Analytic Approach

2.4.2. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Statistical Analysis

3.1.1. Sample

3.1.2. Emotional Health and Wellbeing Scores

3.1.3. Resilience (Mindfulness and Self-Compassion)

3.1.4. Mental Health (Perceived Stress and Wellbeing)

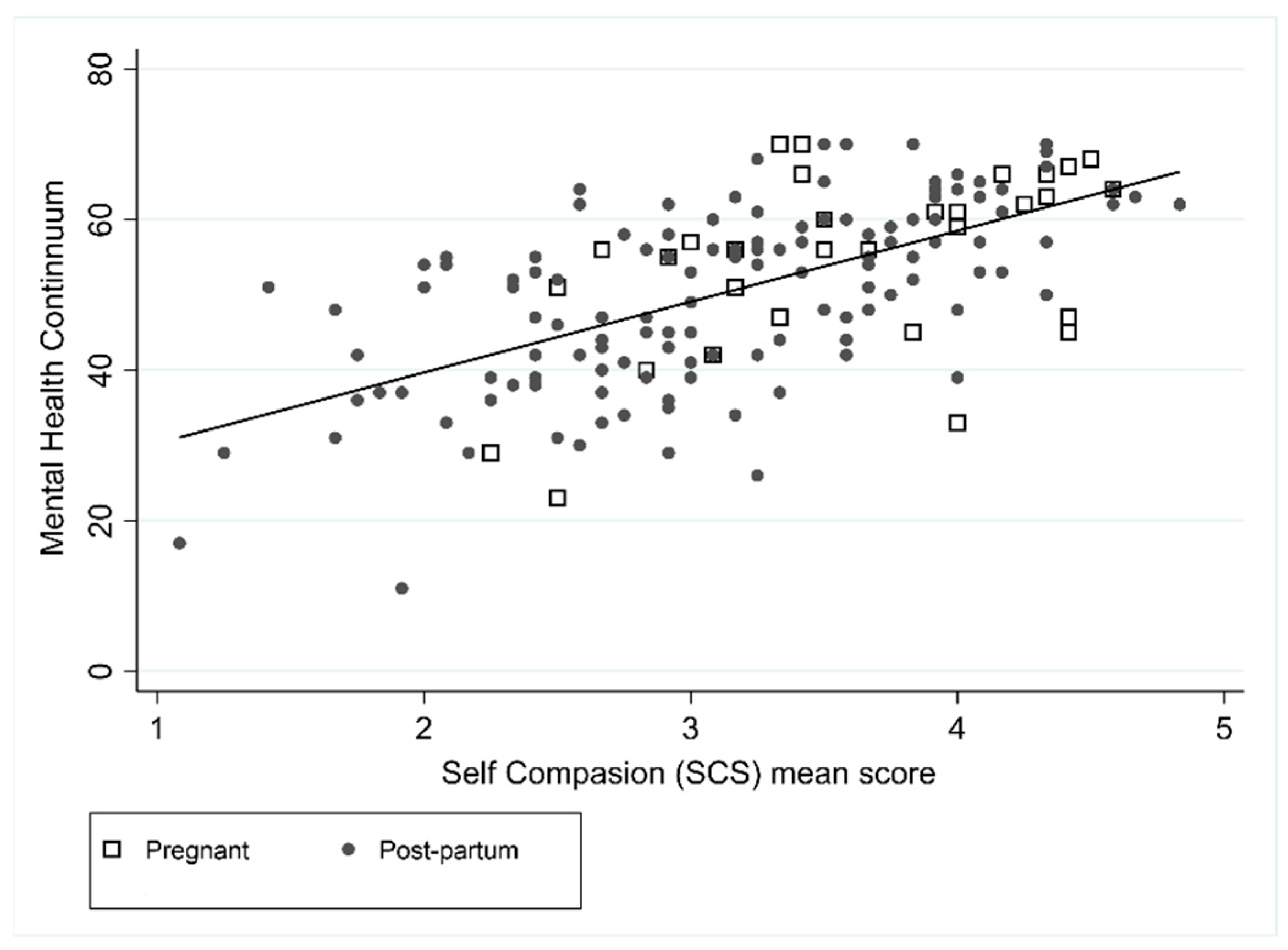

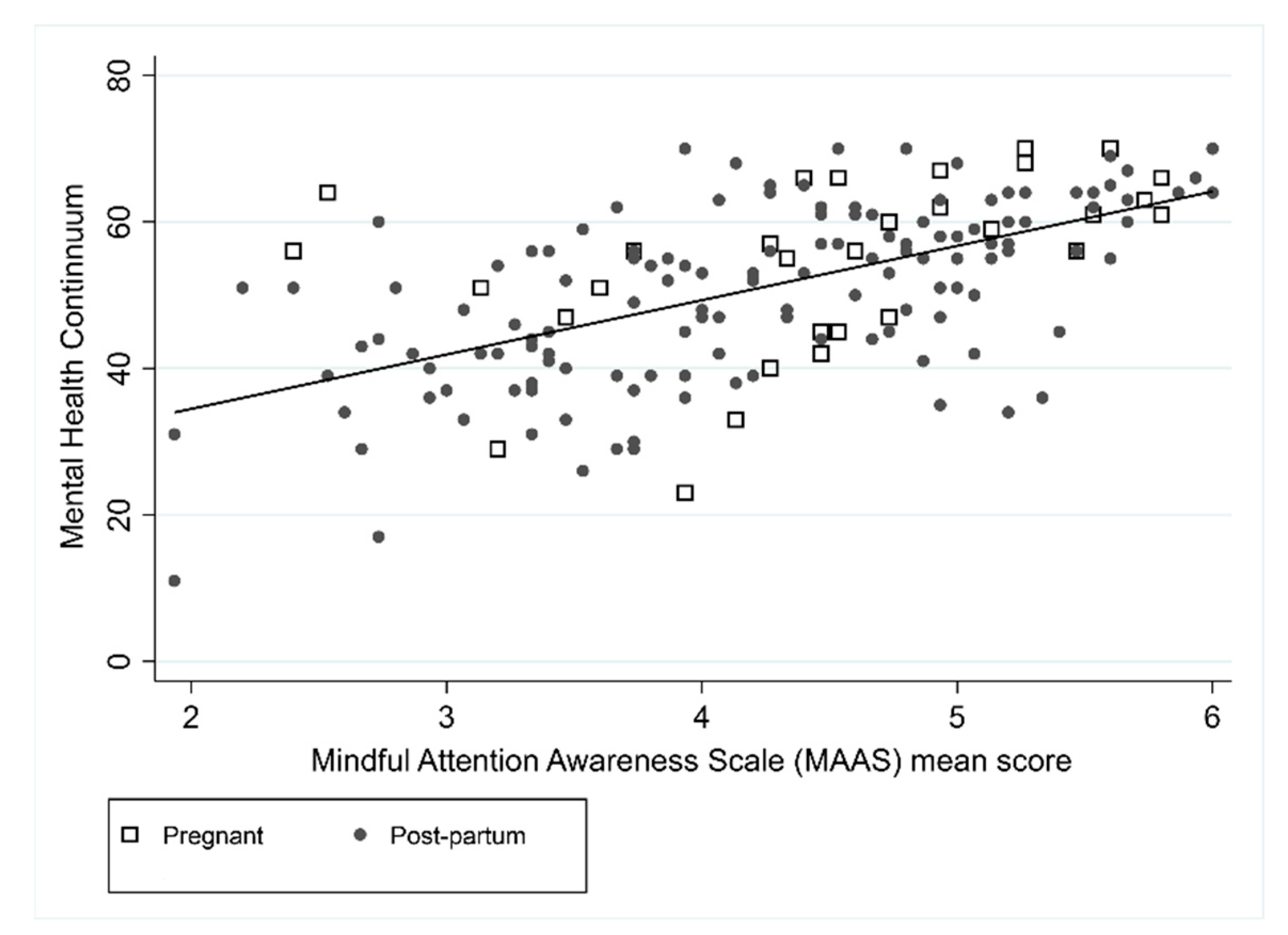

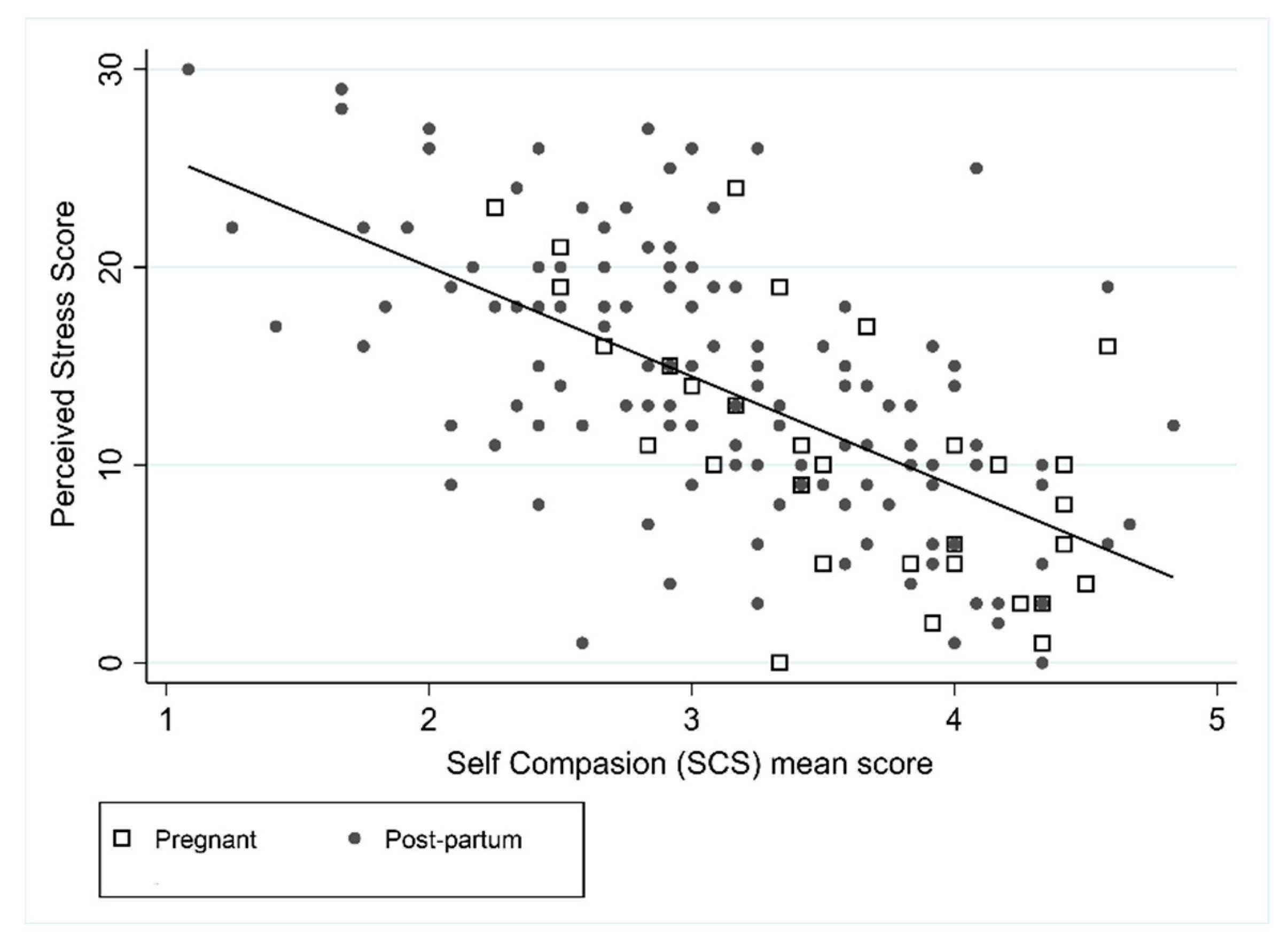

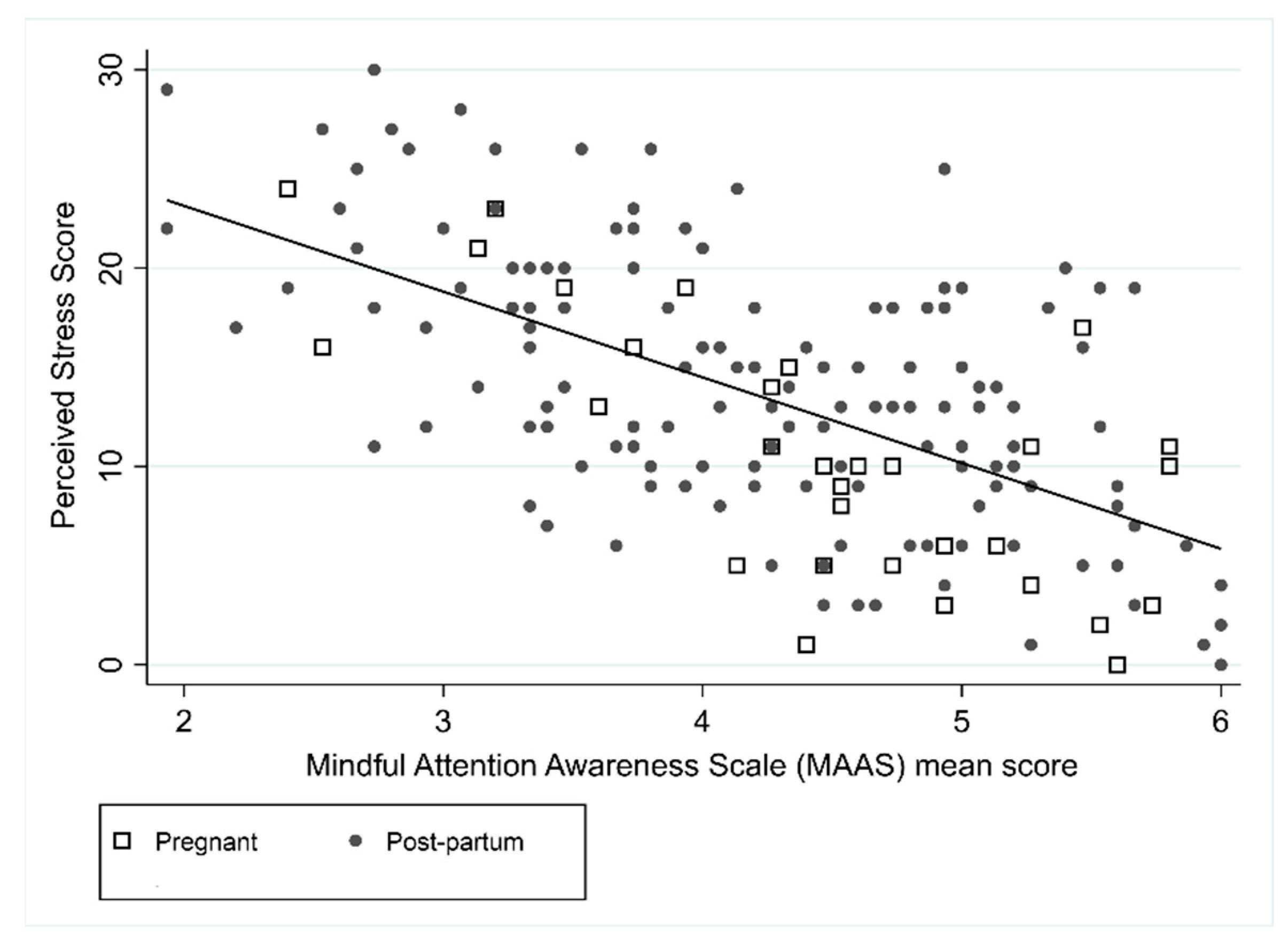

3.1.5. Associations between Variables

3.1.6. Information-Seeking and Utilisation of Services to Support Women’s Emotional Needs

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Theme 1: Impact of COVID-19 on Psychological Care

- (a)

- Psychological Distress:

“I was really anxious. I did a calm birth course to try and help me just get some that sense of control back in a world where everything was so uncertain. So, I was just really stressed out … I just feel like pregnant women weren’t supported through the pandemic … You’re just thrown in the complete deep end because you don’t have regular support that you’d normally have.”(CW6_low)

- (b)

- Lack of Face-to-Face Service Access:

“There was no face-to-face and just calling someone on the phone, it felt it was a bit impersonal. So, I relied heavily on my family to deal with my, you know, my anxiety and my outbursts and just being frightened for those few weeks.”(CW1_high)

“It’s not until you’re in that deep, dark place that you need that help and someone can tell you, whereas if I’d known about it before, I might not have gotten to that point.”(CW9_high)

“… so I felt like I was taking away from other people by asking such a simple question but, really, it could have been a big deal for all I knew … I was not caring to myself, I was to my baby, I’m two people now and I needed that appointment just as much as anyone else.”(CW9_high)

- (c)

- Hospital Restrictions:

“When they cancelled everything, it took weeks for them to do anything online and then it was pages of reading, there’s no videos, no nothing, and then you have all these questions, and you try to call to find out some answers and no one can give you any answers and there was no one to talk to.”(CW4_low)

3.2.2. Theme 2: Isolation from Family and Friends

- (a)

- Social Isolation

“It was quite sad that I couldn’t even share my pregnancy experience—as scary as it was, I couldn’t share that with anyone, and I feel like I missed out.”(CW9_high)

“There’s a whole group of mothers out there that are just there by themselves.”(CW10_high)

- (b)

- Lack of Birth Support Person

3.2.3. Theme 3: Need for Increased Information and Support Needs

- (a)

- Increased Access to Child Health Nurses

“For six months, there’s a whole group of mothers from late February to March/April that were just forgotten about and those mothers, some of them now at nine months make no connections with any other mothers because they were just left.”(CW10_high)

- (b)

- Peer Support

“Just to be able to obviously talk to other people that were going through basically the same things just made it all a little bit easier.”(CW4_low)

“Having those people that we’re going through the exact same as what I was was really helpful.”(CW14_low)

- (c)

- Virtual Support

“I didn’t have one successful phone call appointment.”(CW14_low)

“I think that initial phone conversation when my anxiety levels are quite high, I just shut it down and then didn’t access services for a while.”(CW11_low)

- (d)

- Clear Information That Is Equitable and Easily Accessible

“… being able to speak to other women in the same situation and they have their coping mechanism and what they’re doing, that might help as well.”(CW2_high)

“You shouldn’t have to be going private to get this information because it’s really just standard information that anyone should be getting … you shouldn’t have to pay that amount of money to get what’s really a basic human right to understand and to get.”(CW4_ow)

[The information] … it’s just too complicated for a normal person to understand it. We’re not medics, we’re not in that field, so you’re just like, “What exactly are you trying to say?”(CW4_low)

“It would have been useful to maybe have some generic information that went out to women in that situation, if you were pregnant, [for example], “It’s early days. We don’t know what the impact could be.” … Statements from a medical professional to put people’s minds at ease.”(CW5_low)

3.2.4. Theme 4: Positive Outcomes

- (a)

- Time to Bond

“I know a lot of us saw the benefits of a reduction in visitors … We were able to use coronavirus as an excuse just to stay in our little bubble.”(CW1_high)

“In fact, if anything I didn’t feel any pressure to go out and see people, I could just relax at home … I suppose the one good thing about not having everyone come over and visit was having that time to adjust to having a baby without lots of visitors and lots of expectations to host for people.”(CW5_low)

“It’s quite nice being less sociable … It’s quite nice not having all these different appointments booked in to see people. I think it just made everyone slow down a little bit.”(CW11_low)

- (b)

- Flexible Working Arrangements

“Working from home is quite a lot better and it definitely made my pregnancy a lot easier working from home.”(CW11_low)

“It’s been really great that my husband had been able to work from home a lot throughout the year … So, if that’s one thing that we could keep, would be him to continue to work from home.”(CW3_high)

- (c)

- Reaching a New ‘Normal’

“I’ve made [exercise] more of a lifestyle that I just do every day rather than going to the gym or going to a class which I think the pandemic had made us do that kind of thing a bit more.”(CW14_low)

“Everyone’s been wonderful. We’re just loving life at the moment. Yeah, absolutely. 2020 has been different, it’s had its moments, but overall, it’s been a great year for us.”(CW3_high)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Measure | Total (N = 174) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (SD) | 33.2 (4.6) |

| Estimated Delivery Date | |

| July–Dec 2019 | 65 (37.4%) |

| Jan–June 2020 | 73 (42.0%) |

| July–Dec 2020 | 36 (20.7%) |

| Education | |

| Less than year 10 | 1 (0.6%) |

| Year 10 | 6 (3.9%) |

| Year 12 | 25 (16.2%) |

| Trade | 18 (11.7%) |

| Bachelor | 56 (36.4%) |

| Post Grad | 33 (21.4%) |

| Other | 15 (9.7%) |

| Income per Year | |

| Up to $25,000 | 2 (1.3%) |

| $25,000 to $50,000 | 6 (3.9%) |

| $50,000 to $75,000 | 13 (8.4%) |

| $75,000 to $100,000 | 23 (14.9%) |

| $100,000 to $150,000 | 52 (33.8%) |

| more than $150,000 | 52 (33.8%) |

| Don’t Know | 3 (1.9%) |

| Opt Out | 3 (1.9%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Australian | 36 (23.2%) |

| New Zealand | 3 (1.9%) |

| British/Irish | 73 (47.1%) |

| European | 11 (7.1%) |

| North African and Middle Eastern | 2 (1.3%) |

| Asian | 19 (12.3%) |

| American | 2 (1.3%) |

| African | 1 (0.6%) |

| Not specified | 8 (5.2%) |

| SES: IRSD quintiles | |

| 1, most disadvantaged | 13 (7.5%) |

| 2 | 7 (4.0%) |

| 3 | 42 (24.1%) |

| 4 | 50 (28.7%) |

| 5, least disadvantaged | 62 (35.6%) |

| Behavioural Questions | Postnatal | Pregnant | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 143) | (n = 31) | (n = 174) | ||

| Since April 2020, have you sought information about your emotional wellbeing from media? | 0.204 | |||

| No | 128 (89.5%) | 28 (90.3%) | 156 (89.7%) | |

| Yes | 15 (10.5%) | 2 (6.5%) | 17 (9.8%) | |

| Do not wish to answer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| How frequently have you sought information from the media? | 0.816 | |||

| Every few weeks | 3 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | |

| Weekly | 3 (20.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (23.5%) | |

| Every few days | 4 (26.7%) | 1 (50.0%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| Daily | 5 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (29.4%) | |

| Have you received information from your workplace about your emotional wellbeing? | 0.167 | |||

| No | 108 (75.5%) | 19 (61.3%) | 127 (73.0%) | |

| Yes | 31 (21.7%) | 11 (35.5%) | 42 (24.1%) | |

| Do not wish to answer | 4 (2.8%) | 1 (3.2%) | 5 (2.9%) | |

| How frequently have you received information from your workplace? | 0.057 | |||

| Every few weeks | 13 (41.9%) | 6 (54.5%) | 19 (45.2%) | |

| Weekly | 15 (48.4%) | 2 (18.2%) | 17 (40.5%) | |

| Every few days | 1 (3.2%) | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (9.5%) | |

| Daily | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Do you seek information from family and friends about your emotional wellbeing? | 0.101 | |||

| No | 107 (74.8%) | 20 (64.5%) | 127 (73.0%) | |

| Yes | 36 (25.2%) | 10 (32.3%) | 46 (26.4%) | |

| Do not wish to answer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| How frequently have you sought information from your family and friends? | 0.118 | |||

| Every few weeks | 12 (33.3%) | 6 (60.0%) | 18 (39.1%) | |

| Weekly | 10 (27.8%) | 4 (40.0%) | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Every few days | 11 (30.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (23.9%) | |

| Daily | 3 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Have you been in direct contact with a healthcare professional during the last few months? | 0.629 | |||

| No | 110 (77.5%) | 26 (83.9%) | 136 (78.6%) | |

| Yes | 32 (22.5%) | 5 (16.1%) | 37 (21.4%) | |

| Was this in person or via a telehealth consultation? | 0.307 | |||

| Telehealth consultation | 9 (28.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (24.3%) | |

| Person | 23 (71.9%) | 5 (100.0%) | 28 (75.7%) | |

| If it was via telehealth, was this consult effective for you? | ||||

| No | 3 (33.3%) | Missing | 3 (33.3%) | |

| Yes | 6 (66.7%) | Missing | 6 (66.7%) | |

| If you haven’t used telehealth, would you be receptive to this? | 0.640 | |||

| No | 4 (17.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (14.3%) | |

| Yes | 18 (78.3%) | 5 (100.0%) | 23 (82.1%) | |

| Do not wish to answer | 1 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.6%) | |

| Have you accessed online support for your emotional wellbeing? | 0.691 | |||

| No | 132 (93.0%) | 30 (96.8%) | 162 (93.6%) | |

| Yes | 10 (7.0%) | 1 (3.2%) | 11 (6.4%) | |

| What type of support have you accessed? | 0.364 | |||

| Apps | 3 (30.0%) | 1 (100.0%) | 4 (36.4%) | |

| Websites | 7 (70.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (63.6%) | |

| If you were to access online support, what type of support do you think you would be helpful? | 0.167 | |||

| n/A | 25 (18.9%) | 9 (30.0%) | 34 (21.0%) | |

| Apps | 30 (22.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | 34 (21.0%) | |

| Websites | 75 (56.8%) | 15 (50.0%) | 90 (55.6%) | |

| Webinars | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (1.2%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (1.2%) |

References

- Bai, H.M. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 8, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Veldhuis, C.B.; Nesoff, E.D.; McKowen, A.L.W.; Rice, D.R.; Ghoneima, H.; Wootton, A.R.; Papautsky, E.L.; Arigo, D.; Goldberg, S.; Anderson, J.C. Addressing the critical need for long-term mental health data during the COVID-19 pandemic: Changes in mental health from April to September 2020. Prev. Med. 2021, 146, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.H.; Jackson, B.; Guelfi, K.; Nguyen, T.; Dimmock, J.A. Understanding and alleviating maternal postpartum distress: Perspectives from first-time mothers in Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 204, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, E.; St John, W. Maternal distress: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2104–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Experience of Perinatal Depression: Data from the 2010 Australian National Infant Feeding Survey; In Information Paper; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Buist, A.; Barnett, B.; Milgrom, J.; Hayes, B.; Ellwood, D.; Speelman, C.; Condon, J. The beyondblue Australian national postnatal depression program 2001–5. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2007, 28, 12. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/beyondblue-australian-national-postnatal/docview/197699969/se-2?accountid=14681 (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Wolford, E.; Lahti, M.; Tuovinen, S.; Lahti, J.; Lipsanen, J.; Savolainen, K.; Räikkönen, K. Maternal depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy are associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in their 3- to 6-year-old children. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2018, in Australia’s Health Series; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, S.L.; Diop, H.; Declercq, E.; Cabral, H.J.; Fox, M.P.; Wise, L.A. Stressful Events During Pregnancy and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barker, D. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clin. Sci. 1998, 95, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 1990, 301, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dubos, R.J. Man Adapting. Mrs Hepsa Ely Silliman Memorial Lectures; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Renz, H.; Holt, P.G.; Inouye, M.; Logan, A.C.; Prescott, S.L.; Sly, P. An exposome perspective: Early-life events and immune development in a changing world. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohr, D.C.; Ho, J.; Duffecy, J.; Baron, K.G.; Lehman, K.A.; Jin, L.; Reifler, D. Perceived barriers to psychological treatments and their relationship to depression. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 66, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozd, F.; Haga, S.M.; Brendryen, H.; Slinning, K. An Internet-Based Intervention (Mamma Mia) for Postpartum Depression: Mapping the Development from Theory to Practice. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2015, 4, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayakhot, P.; Carolan-Olah, M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hagemann, E.; Silva, D.T.; Davis, J.A.; Gibson, L.Y.; Prescott, S.L. Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD): The importance of life-course and transgenerational approaches. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lamers, S.M.; Westerhof, G.J.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Klooster, P.T.; Keyes, C.L. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). J. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.G.; Ørnbøl, E.; Vestergaard, M.; Bech, P.; Larsen, F.B.; Lasgaard, M.; Christensen, K.S. The construct validity of the Perceived Stress Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 84, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity 2003, 2, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lennard, G.R.; Mitchell, A.E.; Whittingham, K. Randomized controlled trial of a brief online self-compassion intervention for mothers of infants: Effects on mental health outcomes. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lönnberg, G.; Jonas, W.; Bränström, R.; Nissen, E.; Niemi, M. Long-term Effects of a Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting Program—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Duarte, J.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. The Origins of Fears of Compassion: Shame and Lack of Safeness Memories, Fears of Compassion and Psychopathology. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 804–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, H.; Mercuri, K.; Judd, F.; Brown, S.J. Antenatal mindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: A pilot randomised controlled trial of the MindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternity hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felder, J.N.; Lemon, E.; Shea, K.; Kripke, K.; Dimidjian, S. Role of self-compassion in psychological well-being among perinatal women. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelman, A.R.; Evare, B.S.; Barrera, A.Z.; Muñoz, R.F.; Gilbert, P. A proof-of-concept pilot randomized comparative trial of brief Internet-based compassionate mind training and cognitive-behavioral therapy for perinatal and intending to become pregnant women. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2018, 25, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.; Heo, J.M.; Gim, W.S. An Examination of the Possibility of Loving-Kindness and Compassion Meditation for Pregnant Women: A Preliminary Study. Stress 2017, 25, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neff, K.D.; Germer, C.K. A Pilot Study and Randomized Controlled Trial of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 69, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, J.; Brimson, J.; Lynch, S. Mindfulness Interventions Delivered by Technology Without Facilitator Involvement: What Research Exists and What Are the Clinical Outcomes? Mindfulness 2016, 7, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Monshat, K.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Burns, J.; Herrman, H. Mental health promotion in the Internet age: A consultation with Australian young people to inform the design of an online mindfulness training programme. Heal. Promot. Int. 2011, 27, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finlay-Jones, A.L.; Davis, J.A.; O’Donovan, A.; Kottampally, K.; Ashley, R.A.; Silva, D.; Ohan, J.L.; Prescott, S.L.; Downs, J. Comparing Web-Based Mindfulness With Loving-Kindness and Compassion Training for Promoting Well-Being in Pregnancy: Protocol for a Three-Arm Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e19803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.T.; Hagemann, E.; Davis, J.A.; Gibson, L.Y.; Srinivasjois, R.; Palmer, D.J.; Colvin, L.; Tan, J.; Prescott, S.L. Introducing the ORIGINS project: A community-based interventional birth cohort. Rev. Environ. Health 2020, 35, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement Instruments | Postnatal | Pregnant | Total | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) Mean Score | n = 139 | n = 31 | n = 170 | 0.169 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.9) | |

| Range | 1.9, 6.0 | 2.4, 5.8 | 1.9, 6.0 | |

| Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) Total Mean Score | n = 136 | n = 31 | n = 167 | 0.003 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.8) | |

| Range | 1.1, 4.8 | 2.3, 4.6 | 1.1, 4.8 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) Total Score | n = 141 | n = 31 | n = 172 | 0.009 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.0 (6.6) | 10.5 (6.6) | 13.4 (6.7) | |

| Range | 0.0, 30.0 | 0.0, 24.0 | 0.0, 30.0 | |

| Mental Health Continuum (MHC-SF) Total Score | n = 140 | n = 31 | n = 171 | 0.086 |

| Mean (SD) | 50.5 (11.8) | 54.6 (12.1) | 51.3 (11.9) | |

| Range | 11.0, 70.0 | 23.0, 70.0 | 11.0, 70.0 |

| Univariable (Unadjusted) Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Continuum (MHC) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | |||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | Coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Self-compassion (SCS) | 9.4 (7.5, 11.3) | p < 0.001 | −5.5 (−6.6, −4.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Intercept | 20.8 (14.6, 27.0) | p < 0.001 | 31.1 (27.6, 34.6) | p < 0.001 |

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | 7.4 (5.9, 9.0) | p < 0.001 | −4.3 (−5.2, −3.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Intercept | 19.6 (12.8, 26.4) | p < 0.001 | 31.8 (30.0, 35.6) | p < 0.001 |

| Pregnant (Yes/No) | 4.1 (−0.6, 8.7) | p = 0.086 | −3.5 (−6.0, −0.9) | p = 0.009 |

| Intercept | 50.5 (48.6, 52.5) | p < 0.001 | 14.0 (12.9, 15.1) | p < 0.001 |

| Multivariable (Adjusted) Model | ||||

| Mental Health Continuum (MHC) | Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | |||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | pValue | Coefficient (95% CI) | pValue | |

| Self-compassion (SCS) | 6.1 (3.9, 8.3) | p < 0.001 | −3.6 (−4.8, −2.3) | p < 0.001 |

| Mindfulness (MAAS) | 4.7 (2.9, 6.4) | p < 0.001 | −2.6 (−3.6, −1.6) | p < 0.001 |

| Pregnant (Yes) | 0.3 (−3.3, 3.8) | p = 0.885 | −1.0 (−3.0, 0.9) | p = 0.302 |

| Intercept | 11.4 (4.7, 18.2) | p = 0.001 | 36.2 (32.4, 39.9) | p < 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davis, J.A.; Gibson, L.Y.; Bear, N.L.; Finlay-Jones, A.L.; Ohan, J.L.; Silva, D.T.; Prescott, S.L. Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136958

Davis JA, Gibson LY, Bear NL, Finlay-Jones AL, Ohan JL, Silva DT, Prescott SL. Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(13):6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136958

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavis, Jacqueline A., Lisa Y. Gibson, Natasha L. Bear, Amy L. Finlay-Jones, Jeneva L. Ohan, Desiree T. Silva, and Susan L. Prescott. 2021. "Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 13: 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136958

APA StyleDavis, J. A., Gibson, L. Y., Bear, N. L., Finlay-Jones, A. L., Ohan, J. L., Silva, D. T., & Prescott, S. L. (2021). Can Positive Mindsets Be Protective Against Stress and Isolation Experienced during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Mixed Methods Approach to Understanding Emotional Health and Wellbeing Needs of Perinatal Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136958