Continence Recovery After Radical Prostatectomy: Personalized Rehabilitation and Predictors of Treatment Outcome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design Consideration

2.1.1. Rehabilitation Protocol

2.1.2. Detailed First Session Procedure

2.1.3. Adherence and Dose

2.1.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Urinary Incontinence

3.1.1. Differences in Incontinence Severity by UI Stage at Baseline

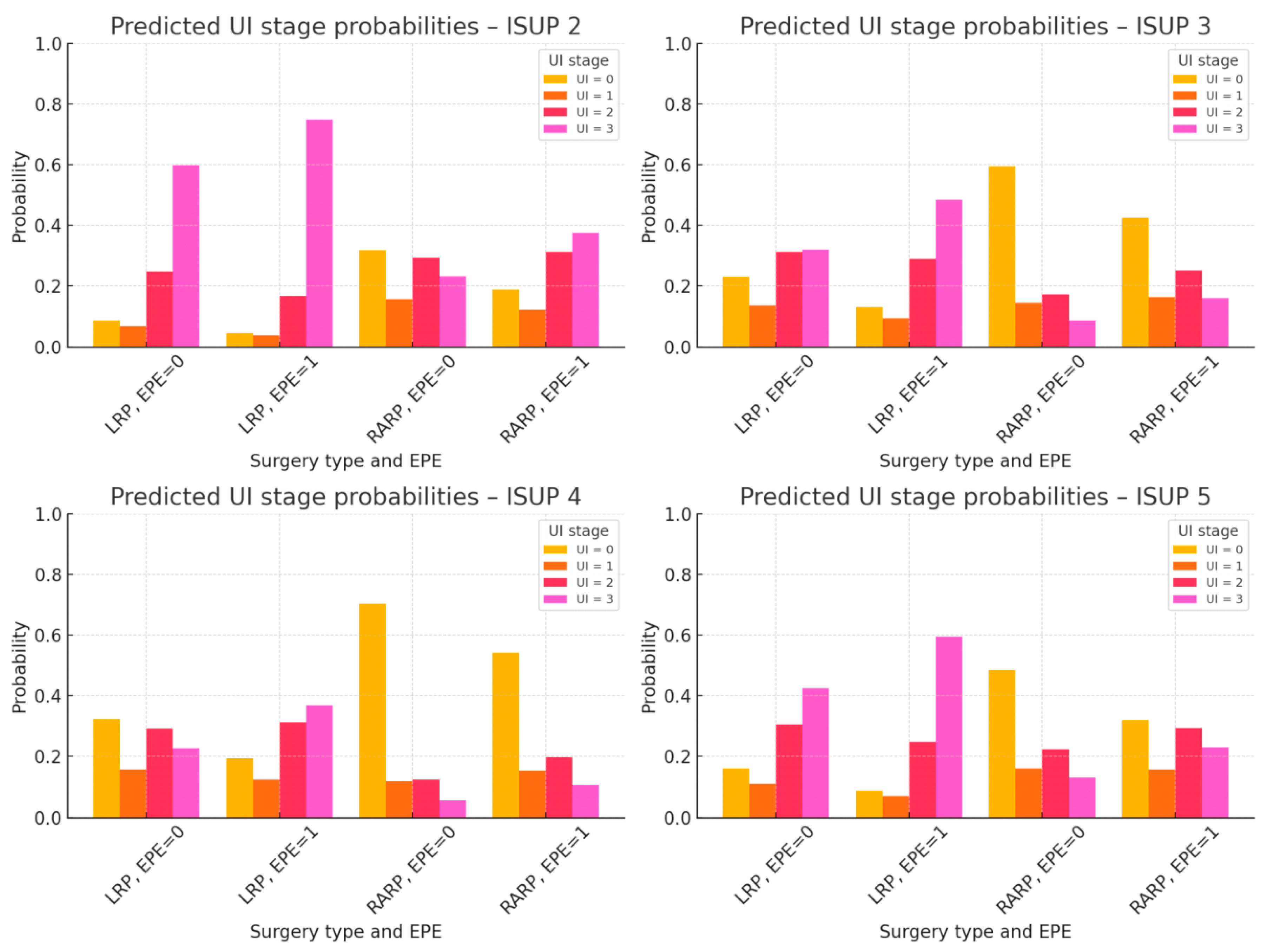

3.1.2. Predictors of Baseline UI Stage—Ordinal Logistic Regression

3.2. Effects of Rehabilitation and Factors Associated with Improvement

3.2.1. Change in Continence Status over Time

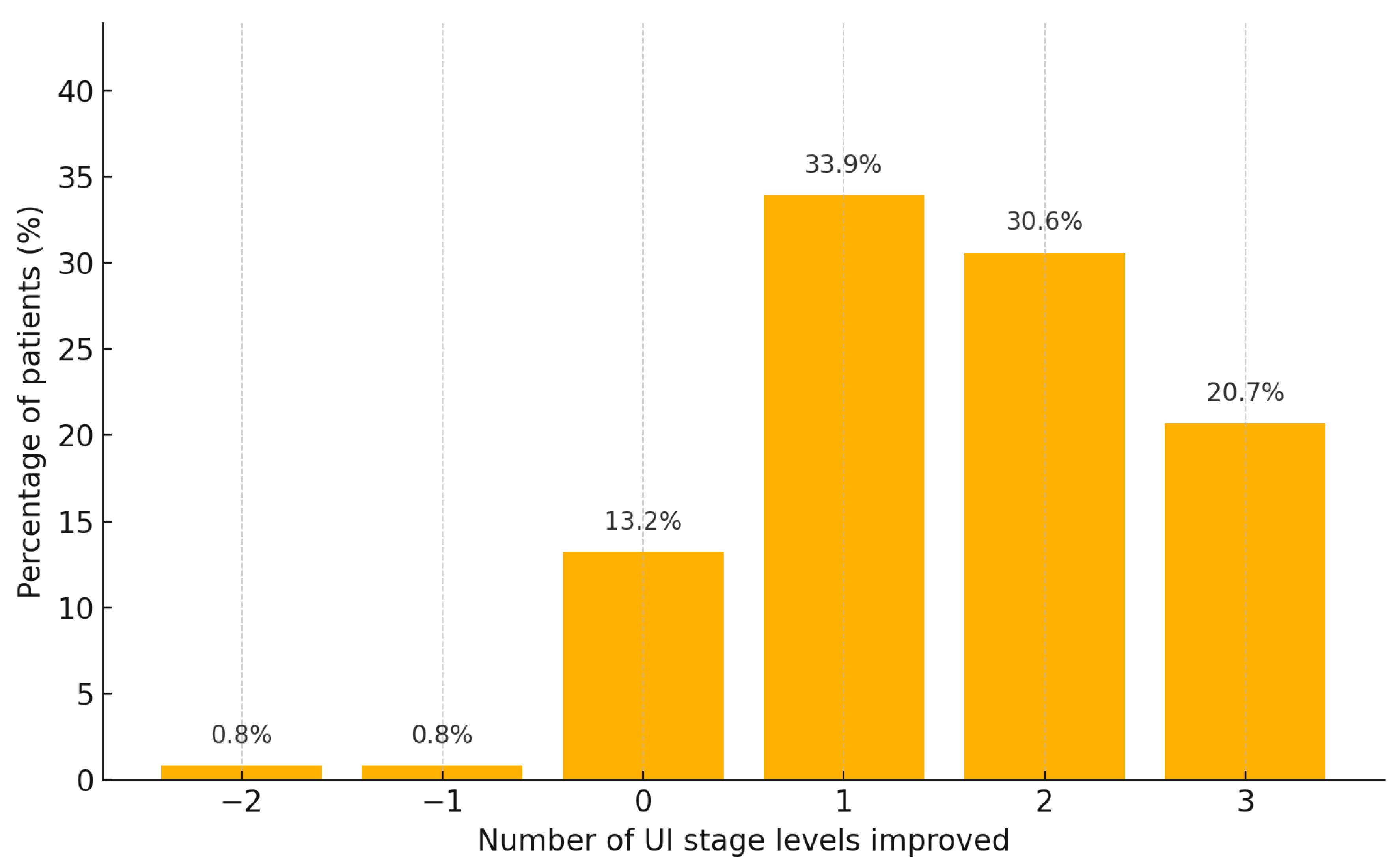

3.2.2. Factors Associated with Improvement in UI Stage

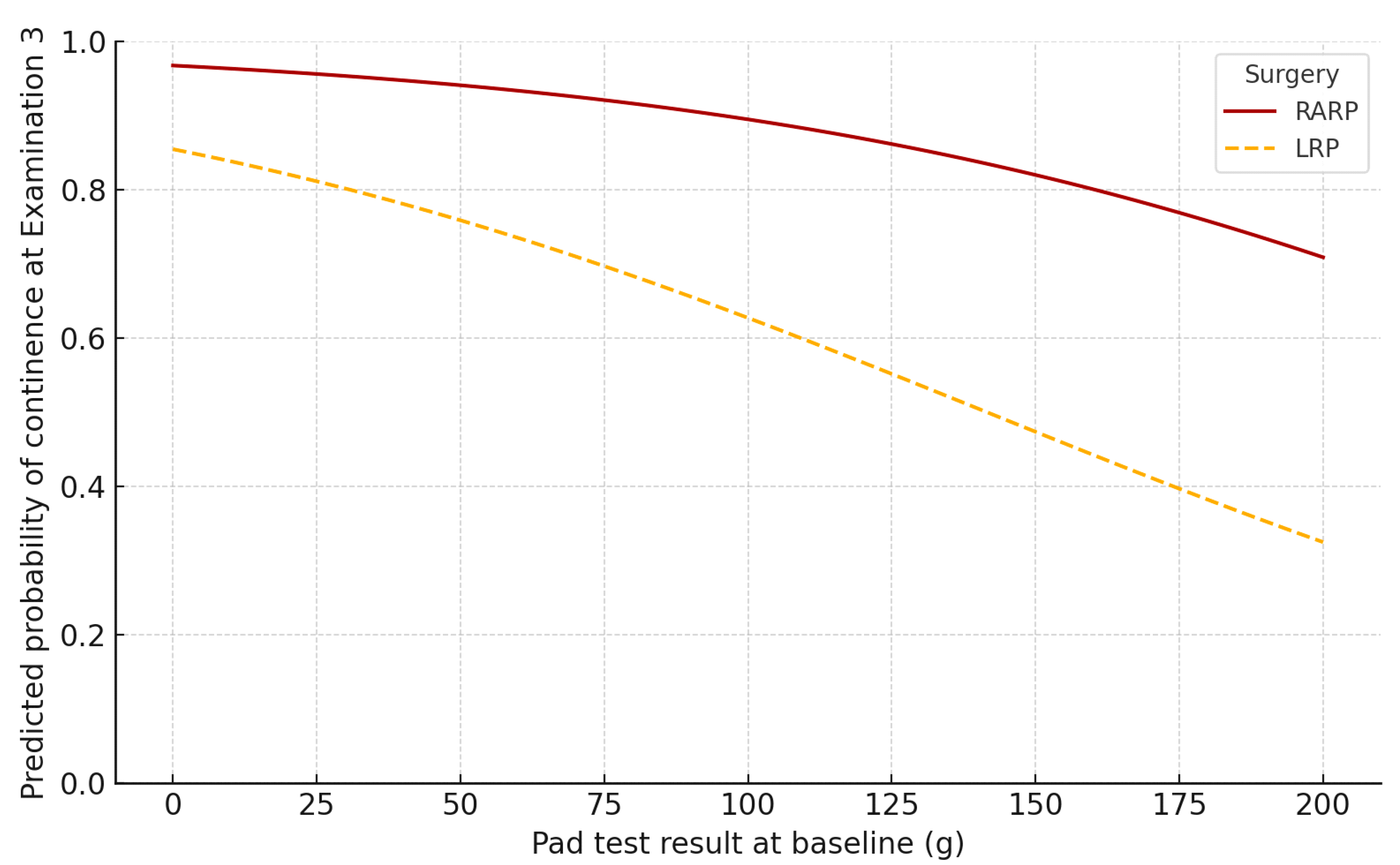

3.2.3. Achievement of Continence at the End of Therapy (Examination 3)

3.2.4. Likelihood of Completing Rehabilitation After the Second Visit

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.03 (−0.01, 0.08) | 0.1376 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.02 (−0.1, 0.06) | 0.5775 |

| Rehabilitation before surgery (Yes vs. No) | −0.69 (−1.43, 0.06) | 0.0708 |

| Time to rehabilitation (days) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | 0.4349 |

| Type of surgery (RARP vs. LRP) | −1.64 (−2.29, −1.0) | <0.001 |

| PSA before surgery (ng/mL) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | 0.5066 |

| EPE1 vs. EPE 0 | 0.87 (0.1, 1.63) | 0.0266 |

| EPE2 vs. EPE 0 | 0.20 (−1.57, 1.96) | 0.8282 |

| SVI (Yes vs. No) | −0.55 (−1.69, 0.58) | 0.3386 |

| ISUP 2 vs. ISUP 1 | −1.43 (−2.57, −0.3) | 0.0135 |

| ISUP 3 vs. ISUP 1 | −1.07 (−2.15, 0.01) | 0.0516 |

| ISUP 4 vs. ISUP 1 | −1.58 (−2.73, −0.42) | 0.0076 |

| ISUP 5 vs. ISUP 1 | −0.43 (−1.88, 1.02) | 0.5605 |

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Pad test result at baseline (g) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 0.0006 |

| Age (years) | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.1) | 0.1325 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.04 (−0.06, 0.14) | 0.4341 |

| Time to rehabilitation (days) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05) | 0.0348 |

| PSA before surgery (ng/mL) | −0.0 (−0.05, 0.04) | 0.8366 |

| Rehabilitation before surgery (Yes vs. No) | 0.22 (−0.68, 1.12) | 0.6314 |

| Type of surgery (RARP vs. LRP) | −0.7 (−1.59, 0.18) | 0.1192 |

| EPE 1 vs. EPE 0 | 0.52 (−0.4, 1.45) | 0.2664 |

| EPE 2 vs. EPE 0 | −0.02 (−2.08, 2.03) | 0.9834 |

| SVI (Yes vs. No) | 0.12 (−1.27, 1.5) | 0.871 |

| ISUP 2 vs. ISUP 1 | −1.78 (−3.29, −0.27) | 0.021 |

| ISUP 3 vs. ISUP 1 | −0.73 (−2.09, 0.62) | 0.29 |

| ISUP 4 vs. ISUP 1 | −0.27 (−1.74, 1.2) | 0.722 |

| ISUP 5 vs. ISUP 1 | −1.0 (−2.72, 0.71) | 0.2522 |

References

- Bahlburg, H.; Rausch, P.; Tully, K.H.; Berg, S.; Noldus, J.; Butea-Bocu, M.C.; Beyer, B.; Müller, G. Urinary Continence Outcomes, Surgical Margin Status, and Complications after Radical Prostatectomy in 2141 German Patients Treated in One High-Volume Inpatient Rehabilitation Clinic in 2022. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellan, P.; Ferretti, S.; Litterio, G.; Marchioni, M.; Schips, L. Management of Urinary Incontinence Following Radical Prostatectomy: Challenges and Solutions. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.A.; Omar, M.I.; Campbell, S.E.; Hunter, K.F.; Cody, J.D.; Glazener, C.M.A. Conservative Management for Postprostatectomy Urinary Incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD001843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farraj, H.; Alriyalat, S. Urinary Incontinence Following Robotic-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e53058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, M.S.; Melmed, G.Y.; Nakazon, T. Life After Radical Prostatectomy: A Longitudinal Study. J. Urol. 2001, 166, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficarra, V.; Novara, G.; Rosen, R.C.; Artibani, W.; Carroll, P.R.; Costello, A.; Menon, M.; Montorsi, F.; Patel, V.R.; Stolzenburg, J.-U.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Reporting Urinary Continence Recovery after Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, M.; Tazawa, M.; Takahashi, K.; Naruse, J.; Oda, K.; Kano, T.; Uchida, T.; Umemoto, T.; Ogawa, T.; Kawamura, Y.; et al. Variations in Predictors for Urinary Continence Recovery at Different Time Periods Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Asian J. Endosc. Surg. 2024, 17, e13243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, D.-H.; Yang, L.; Shariat, S.F.; Reitter-Pfoertner, S.; Gredinger, G.; Waldhoer, T. Difference in Incontinence Pad Use between Patients after Radical Prostatectomy and Cancer-Free Population with Subgroup Analysis for Open vs. Minimally Invasive Radical Prostatectomy: A Descriptive Analysis of Insurance Claims-Based Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Moore, T.H.M.; Jameson, C.M.; Davies, P.; Rowlands, M.-A.; Burke, M.; Beynon, R.; Savovic, J.; Donovan, J.L. Symptomatic and Quality-of-Life Outcomes after Treatment for Clinically Localised Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. BJU Int. 2016, 118, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, J.S.; Breyer, B.; Comiter, C.; Eastham, J.A.; Gomez, C.; Kirages, D.J.; Kittle, C.; Lucioni, A.; Nitti, V.W.; Stoffel, J.T.; et al. Incontinence after Prostate Treatment: AUA/SUFU Guideline. J. Urol. 2019, 202, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kampen, M.; De Weerdt, W.; Van Poppel, H.; De Ridder, D.; Feys, H.; Baert, L. Effect of Pelvic-Floor Re-Education on Duration and Degree of Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2000, 355, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canning, A.; Raison, N.; Aydin, A.; Cheikh Youssef, S.; Khan, S.; Dasgupta, P.; Ahmed, K. A Systematic Review of Treatment Options for Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 2617–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lira, G.H.S.; Fornari, A.; Cardoso, L.F.; Aranchipe, M.; Kretiska, C.; Rhoden, E.L. Effects of Perioperative Pelvic Floor Muscle Training on Early Recovery of Urinary Continence and Erectile Function in Men Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2019, 45, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacci, M.; De Nunzio, C.; Sakalis, V.; Rieken, M.; Cornu, J.-N.; Gravas, S. Latest Evidence on Post-Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, C.; García Obrero, I.; Muñoz-Calahorro, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, A.J.; Medina-López, R.A. Efficacy of Preoperative-Guided Pelvic Floor Exercises on Urinary Incontinence and Quality of Life after Robotic Radical Prostatectomy. Actas Urol. Esp. Engl. Ed. 2025, 49, 501702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienza, A.; Robles, J.E.; Hevia, M.; Algarra, R.; Diez-Caballero, F.; Pascual, J.I. Prevalence Analysis of Urinary Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy and Influential Preoperative Factors in a Single Institution. Aging Male 2018, 21, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkhasov, R.M.; Lee, T.; Huang, R.; Berkley, B.; Pinkhasov, A.M.; Dodge, N.; Loecher, M.S.; James, G.; Pop, E.; Attwood, K.; et al. Prediction of Incontinence after Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy: Development and Validation of a 24-Month Incontinence Nomogram. Cancers 2022, 14, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto González, M.; Da Cuña Carrera, I.; Gutiérrez Nieto, M.; López García, S.; Ojea Calvo, A.; Lantarón Caeiro, E.M. Early 3-Month Treatment with Comprehensive Physical Therapy Program Restores Continence in Urinary Incontinence Patients after Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2020, 39, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thüroff, J.W.; Abrams, P.; Andersson, K.-E.; Artibani, W.; Chapple, C.R.; Drake, M.J.; Hampel, C.; Neisius, A.; Schröder, A.; Tubaro, A. EAU Guidelines on Urinary Incontinence. Eur. Urol. 2011, 59, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, E.; Yin, S.; Yang, Y.; Ke, C.; Fang, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, D. The Effect of Perioperative Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise on Urinary Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy: A Meta-Analysis. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2023, 49, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberg, H.; Shankar, P.R.; Singh, K.; Caoili, E.M.; George, A.K.; Hackett, C.; Johnson, A.; Davenport, M.S. Preoperative Prostate MRI Predictors of Urinary Continence Following Radical Prostatectomy. Radiology 2022, 303, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungovan, S.F.; Carlsson, S.V.; Gass, G.C.; Graham, P.L.; Sandhu, J.S.; Akin, O.; Scardino, P.T.; Eastham, J.A.; Patel, M.I. Preoperative Exercise Interventions to Optimize Continence Outcomes Following Radical Prostatectomy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangganata, E.; Rahardjo, H.E. The Effect of Preoperative Pelvic Floor Muscle Training on Incontinence Problems after Radical Prostatectomy: A Meta-Analysis. Urol. J. 2021, 18, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, M.; Kitta, T.; Chiba, H.; Higuchi, M.; Abe-Takahashi, Y.; Togo, M.; Kusakabe, N.; Murai, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Matsumoto, R.; et al. Physiotherapy for Continence and Muscle Function in Prostatectomy: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BJU Int. 2024, 134, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorrami, M.-H.; Mohseni, A.; Gholipour, F.; Alizadeh, F.; Zargham, M.; Izadpanahi, M.-H.; Sichani, M.M.; Khorrami, F. Single Session Pre-Operative Pelvic Floor Muscle Training with Biofeedback on Urinary Incontinence and Quality of Life after Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Urol. Sci. 2023, 34, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguas-Gracia, A.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Subirón-Valera, A.B.; Rodríguez-Roca, B.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Satustegui-Dordá, P.J.; Fernández-Rodríguez, M.T.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Tejada-Garrido, C.I.; et al. Quality of Life after Radical Prostatectomy: A Longitudinal Study. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus, C.; Brattås, I.; Volz, D.; Sydén, F.; Grufman, K.H.; Mozer, P.; Renström-Koskela, L. Evaluation of the 24-h Pad Weight Test as Continence Rate Assessment Tool after Artificial Urinary Sphincter Implantation for Postprostatectomy Urinary Incontinence: A Swedish Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2021, 40, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.D.; Cohn, J.A.; Fedunok, P.A.; Chung, D.E.; Bales, G.T. Assessing Variability of the 24-Hour Pad Weight Test in Men with Post-Prostatectomy Incontinence. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2016, 42, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto González, M.; Da Cuña Carrera, I.; Lantarón Caeiro, E.M.; Gutiérrez Nieto, M.; López García, S.; Ojea Calvo, A. Correlation between the 1-Hour and 24-Hour Pad Test in the Assessment of Male Patients with Post-Prostatectomy Urinary Incontinence. Progrès En Urol. 2018, 28, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.T.; Patel, M.I.; Mungovan, S.F. Pad Weight, Pad Number, and Incontinence-Related Patient-Reported Outcome Measures After Radical Prostatectomy. Société Int. d’Urologie J. 2022, 3, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, D.J.H.; Reitsma, J.; van Gerwen, L.; Vleghaar, J.; Gehlen, J.M.L.G.; Ziedses des Plantes, C.M.P.; van Basten, J.P.A.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Bruins, H.M.; Collette, E.R.P.; et al. Validation of Claims Data for Absorbing Pads as a Measure for Urinary Incontinence after Radical Prostatectomy, a National Cross-Sectional Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, E.; Campetella, M.; Marino, F.; Gavi, F.; Moretto, S.; Pastorino, R.; Bizzarri, F.P.; Pierconti, F.; Gandi, C.; Bientinesi, R. Preoperative Risk Factors for Failure After Fixed Sling Implantation for Postprostatectomy Stress Urinary Incontinence (FORESEE): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2025, 77, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Chang, C.-L.; Chen, C.-I.; Huang, C.-C. Comparison of Acute and Chronic Surgical Complications Following Robot-Assisted, Laparoscopic, and Traditional Open Radical Prostatectomy Among Men in Taiwan. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2120156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Abad, A.; Server Gómez, G.; Loyola Maturana, J.P.; Giménez Andreu, I.; Collado Serra, A.; Wong Gutiérrez, A.; Boronat Catalá, J.; de Pablos Rodríguez, P.; Gómez-Ferrer, Á.; Casanova Ramón-Borja, J.; et al. Comparative Evaluation of Continence and Potency after Radical Prostatectomy: Robotic vs. Laparoscopic Approaches, Validating LAP-01 Trial. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 55, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchioni, M.; Primiceri, G.; Castellan, P.; Schips, L.; Mantica, G.; Chapple, C.; Papalia, R.; Porpiglia, F.; Scarpa, R.M.; Esperto, F. Conservative Management of Urinary Incontinence Following Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Minerva Urol. Nefrol. 2020, 72, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, B.-H.; Wang, S.; Meng, H.-Z.; Jin, X.-D. Outcomes of Health-Related Quality of Life after Open, Laparoscopic, or Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy in China. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trieu, D.; Ju, I.E.; Chang, S.B.; Mungovan, S.F.; Patel, M.I. Surgeon Case Volume and Continence Recovery Following Radical Prostatectomy: A Systematic Review. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Total Group (n = 182) | UI Stage 0 (n = 64) | UI Stage 1 (n = 23) | UI Stage 2 (n = 47) | UI Stage 3 (n = 48) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.1 (6.5) | 65.5 (6.0) | 63.1 (6.9) | 66.8 (6.7) | 67.7 (6.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.2 (3.6) | 28.0 (3.7) | 27.8 (3.4) | 29.2 (4.0) | 27.8 (3.2) |

| PSA before surgery (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 9.2 (7.8) | 8.4 (4.7) | 11.3 (11.4) | 8.4 (7.4) | 10.0 (9.4) |

| PSA post-surgery (ng/mL), mean (SD) | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.5 (2.8) | 0.1 (0.6) |

| Rehabilitated before surgery, n (%) | |||||

| No | 36 (19.8) | 12.0 (18.8) | 3.0 (13.0) | 6.0 (12.8) | 15.0 (31.3) |

| Yes | 146 (80.2) | 52.0 (81.3) | 20.0 (87.0) | 41.0 (87.2) | 33.0 (68.8) |

| Time to rehabilitation (days), mean (SD) | 36.1 (14.0) | 35.1 (6.0) | 38.9 (13.8) | 36.7 (21.9) | 35.6 (11.8) |

| Pad test result at Examination 1 (g), mean (SD) | 43.9 (68.9) | 3.2 (15.7) | 4.3 (1.8) | 30.1 (12.4) | 130.8 (83.1) |

| Pad test result at Examination 3 (g), mean (SD) | 8.0 (22.9) | 0.4 (1.4) | 0.6 (0.7) | 5.8 (16.4) | 23.7 (37.3) |

| Δ Pad test result (g), mean (SD) | 36.0 (63.4) | 2.9 (15.8) | 3.7 (1.9) | 24.3 (18.9) | 107.1 (86.5) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||||

| LRP | 106 (58.2) | 19.0 (29.7) | 16.0 (69.6) | 36.0 (76.6) | 35.0 (72.9) |

| RARP | 76 (41.8) | 45.0 (70.3) | 7.0 (30.4) | 11.0 (23.4) | 13.0 (27.1) |

| pT, n (%) | |||||

| pT1 | 2 (1.1) | na | 1.0 (4.4) | na | 1.0 (2.1) |

| pT2 | 126 (69.2) | 53.0 (82.8) | 12.0 (52.2) | 34.0 (72.3) | 27.0 (56.3) |

| pT3 | 54 (29.7) | 11.0 (17.2) | 10.0 (43.5) | 13.0 (27.7) | 20.0 (41.7) |

| pN, n (%) | |||||

| Nx | 17 (9.3) | 6.0 (9.4) | 3.0 (13.0) | 4.0 (8.5) | 4.0 (8.3) |

| N0 | 163 (89.6) | 58.0 (90.6) | 20.0 (87.0) | 42.0 (89.4) | 43.0 (89.6) |

| N1 | 2 (1.1) | na | na | 1.0 (2.1) | 1.0 (2.1) |

| pM, n (%) | |||||

| M0 | 161 (88.5) | 60.0 (93.8) | 18.0 (78.3) | 41.0 (87.2) | 42.0 (87.5) |

| M1 | 4 (2.2) | 1.0 (1.6) | 2.0 (8.7) | 1.0 (2.1) | na |

| Mx | 17 (9.34) | 3 (4.7) | 3 (13.1) | 5 (10.6) | 6 (12.5) |

| GS1, n (%) | |||||

| GS1 → 3 | 58 (31.9) | 26.0 (40.6) | 9.0 (39.1) | 8.0 (17.0) | 15.0 (31.3) |

| GS1 → 4 | 121 (66.5) | 38.0 (59.4) | 14.0 (60.9) | 37.0 (78.7) | 32.0 (66.7) |

| GS1 → 5 | 3 (1.6) | na | na | 2.0 (4.3) | 1.0 (2.1) |

| GS2, n (%) | |||||

| GS2 → 3 | 77 (42.3) | 22.0 (34.4) | 11.0 (47.8) | 22.0 (46.8) | 22.0 (45.8) |

| GS2 → 4 | 89 (48.9) | 38.0 (59.4) | 11.0 (47.8) | 18.0 (38.3) | 22.0 (45.8) |

| GS2 → 5 | 16 (8.8) | 4.0 (6.3) | 1.0 (4.4) | 7.0 (14.9) | 4.0 (8.3) |

| GS, n (%) | |||||

| GS → 6 | 16 (8.8) | 4.0 (6.3) | 3.0 (13.0) | 4.0 (8.5) | 5.0 (10.4) |

| GS → 7 | 100 (54.9) | 38.0 (59.4) | 14.0 (60.9) | 21.0 (44.7) | 27.0 (56.3) |

| GS → 8 | 50 (27.5) | 20.0 (31.3) | 5.0 (21.7) | 14.0 (29.8) | 11.0 (22.9) |

| GS → 9 | 16 (8.8) | 2.0 (3.1) | 1.0 (4.4) | 8.0 (17.0) | 5.0 (10.4) |

| Persistent PSA, n (%) | |||||

| No | 158 (86.8) | 56.0 (87.5) | 19.0 (82.6) | 39.0 (83.0) | 44.0 (91.7) |

| Yes | 24 (13.2) | 8.0 (12.5) | 4.0 (17.4) | 8.0 (17.0) | 4.0 (8.3) |

| EPE, n (%) | |||||

| EPE 0 | 129 (70.9) | 53.0 (82.8) | 14.0 (60.9) | 33.0 (70.2) | 29.0 (60.4) |

| EPE 1 | 47 (25.8) | 10.0 (15.6) | 7.0 (30.4) | 12.0 (25.5) | 18.0 (37.5) |

| EPE 2 | 6 (3.3) | 1.0 (1.6) | 2.0 (8.7) | 2.0 (4.3) | 1.0 (2.1) |

| SVI, n (%) | |||||

| No | 162 (89.0) | 60.0 (93.8) | 18.0 (78.3) | 41.0 (87.2) | 43.0 (89.6) |

| Yes | 20 (11.0) | 4.0 (6.3) | 5.0 (21.7) | 6.0 (12.8) | 5.0 (10.4) |

| EAU, n (%) | |||||

| EAU 1 | 9 (4.9) | 2.0 (3.1) | 3.0 (13.0) | 2.0 (4.3) | 2.0 (4.2) |

| EAU 2 | 139 (76.4) | 56.0 (87.5) | 16.0 (69.6) | 36.0 (76.6) | 31.0 (64.6) |

| EAU 3 | 34 (18.7) | 6.0 (9.4) | 4.0 (17.4) | 9.0 (19.2) | 15.0 (31.3) |

| ISUP, n (%) | |||||

| ISUP 1 | 16 (8.8) | 4.0 (6.3) | 3.0 (13.0) | 4.0 (8.5) | 5.0 (10.4) |

| ISUP 2 | 39 (21.4) | 20.0 (31.3) | 6.0 (26.1) | 3.0 (6.4) | 10.0 (20.8) |

| ISUP 3 | 61 (33.5) | 18.0 (28.1) | 8.0 (34.8) | 18.0 (38.3) | 17.0 (35.4) |

| ISUP 4 | 50 (27.5) | 20.0 (31.3) | 5.0 (21.7) | 14.0 (29.8) | 11.0 (22.9) |

| ISUP 5 | 16 (8.8) | 2.0 (3.1) | 1.0 (4.4) | 8.0 (17.0) | 5.0 (10.4) |

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.0 (−0.05, 0.05) | 0.87 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.01 (−0.1, 0.09) | 0.8582 |

| Rehabilitation before surgery (Yes vs. No) | −1.27 (−2.17, −0.36) | 0.0061 |

| Time to rehabilitation (days) | −0.04 (−0.06, −0.01) | 0.0026 |

| Type of surgery (RARP vs. LRP) | 0.31 (−0.51, 1.14) | 0.4564 |

| PSA before surgery (ng/mL) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.02) | 0.5235 |

| EPE 1 vs. EPE 0 | −0.36 (−1.22, 0.51) | 0.4181 |

| EPE 2 vs. EPE 0 | −1.16 (−3.15, 0.82) | 0.2511 |

| SVI (Yes vs. No) | −0.17 (−1.47, 1.14) | 0.8012 |

| ISUP 2 vs. ISUP 1 | 0.28 (−1.12, 1.67) | 0.698 |

| ISUP 3 vs. ISUP 1 | −0.12 (−1.41, 1.16) | 0.8494 |

| ISUP 4 vs. ISUP 1 | −0.46 (−1.83, 0.91) | 0.511 |

| ISU P5 vs. ISUP 1 | 0.64 (−1.01, 2.29) | 0.4466 |

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Pad test result at baseline (g) | −0.01 (−0.02, −0.01) | 0.0001 |

| Age (years) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.02) | 0.1646 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.03 (−0.15, 0.1) | 0.6887 |

| Rehabilitation before surgery (Yes vs. No) | −0.58 (−1.72, 0.57) | 0.3229 |

| Time to rehabilitation (days) | 0.0 (−0.01, 0.02) | 0.5766 |

| Type of surgery (RARP vs. LRP) | 1.09 (0.02, 2.17) | 0.0468 |

| PSA before surgery (ng/mL) | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.4403 |

| EPE 1 vs. EPE 0 | −0.86 (−1.87, 0.16) | 0.0971 |

| EPE 2 vs. EPE 0 | −0.11 (−2.95, 2.73) | 0.9397 |

| SVI (Yes vs. No) | −0.19 (−1.68, 1.31) | 0.8058 |

| ISUP 2 vs. ISUP 1 | 0.75 (−1.06, 2.56) | 0.4152 |

| ISUP 3 vs. ISUP 1 | 1.07 (−0.68, 2.81) | 0.2302 |

| ISUP 4 vs. ISUP 1 | 0.62 (−1.23, 2.46) | 0.5107 |

| ISUP 5 vs. ISUP 1 | 1.62 (−0.68, 3.92) | 0.1675 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terek-Derszniak, M.; Gąsior-Perczak, D.; Biskup, M.; Skowronek, T.; Nowak, M.; Falana, J.; Jaskulski, J.; Obarzanowski, M.; Gozdz, S.; Macek, P. Continence Recovery After Radical Prostatectomy: Personalized Rehabilitation and Predictors of Treatment Outcome. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222881

Terek-Derszniak M, Gąsior-Perczak D, Biskup M, Skowronek T, Nowak M, Falana J, Jaskulski J, Obarzanowski M, Gozdz S, Macek P. Continence Recovery After Radical Prostatectomy: Personalized Rehabilitation and Predictors of Treatment Outcome. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222881

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerek-Derszniak, Małgorzata, Danuta Gąsior-Perczak, Małgorzata Biskup, Tomasz Skowronek, Mariusz Nowak, Justyna Falana, Jarosław Jaskulski, Mateusz Obarzanowski, Stanislaw Gozdz, and Pawel Macek. 2025. "Continence Recovery After Radical Prostatectomy: Personalized Rehabilitation and Predictors of Treatment Outcome" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222881

APA StyleTerek-Derszniak, M., Gąsior-Perczak, D., Biskup, M., Skowronek, T., Nowak, M., Falana, J., Jaskulski, J., Obarzanowski, M., Gozdz, S., & Macek, P. (2025). Continence Recovery After Radical Prostatectomy: Personalized Rehabilitation and Predictors of Treatment Outcome. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222881