A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Multicomponent Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivors

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

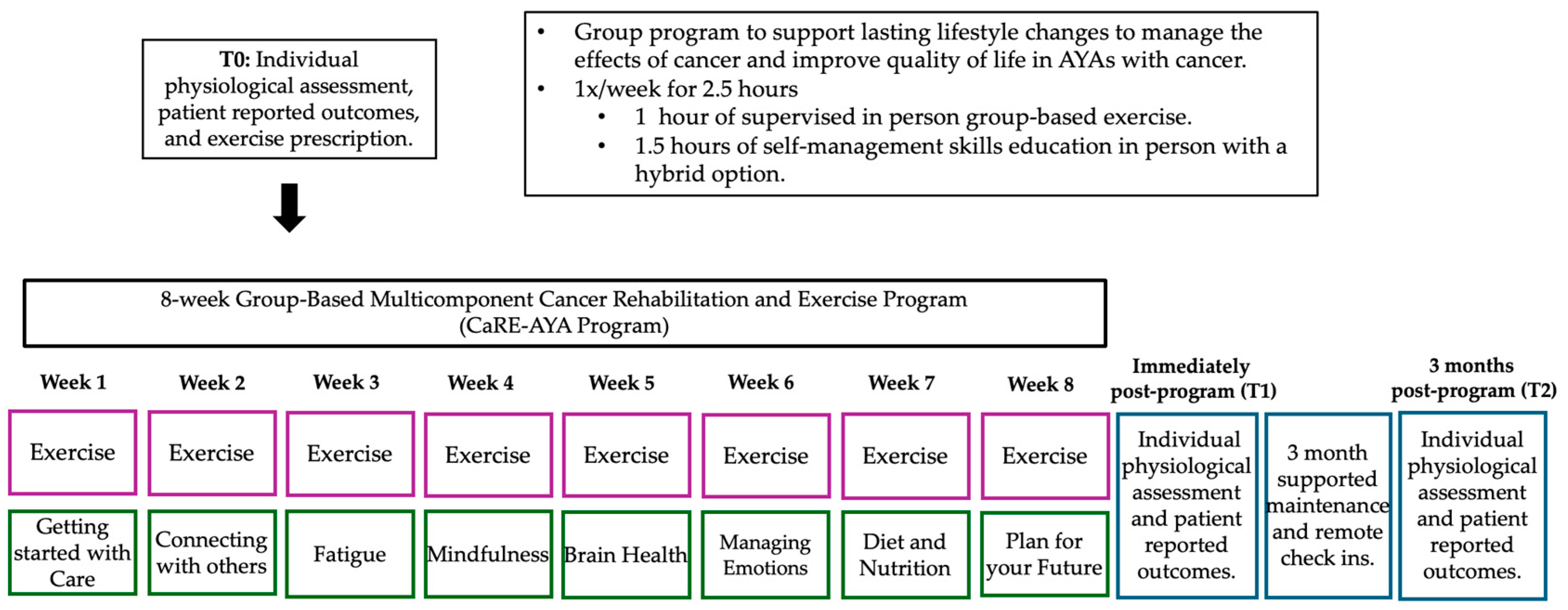

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Study Outcomes

- Disability was measured using the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO-DAS 2.0) [47]. Respondents rate their difficulty in engaging in particular activities on a scale from “none” (no difficulty) to “extreme or cannot do” on six domains of functioning. Scores range from 12 to 60, where higher scores indicate higher disability or loss of function [47].

- Physical functioning was measured using the SF-36 physical functioning score and physical component summary [48]. Participants rate their difficulty in engaging in certain activities on a 6-point scale for each item. The physical functioning subscale includes 10 items. Scores are converted to a 0–100 range. A higher score indicates a more favourable health state [48]. The PCS includes measurements from the physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health subscales.

- Social functioning was measured using the Social Difficulties Inventory (SDI), which was developed for use in cancer care to evaluate different areas of potential difficulty in daily life [49]. Each item measures a different area of potential difficulty in daily life. Item scores are summed to calculate a total score. Scores greater than 10 indicate social distress [49].

- Mood was measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7), which is an efficient tool in the screening and assessment of generalized anxiety disorder [50]. Question response options include “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days” and “nearly every day” scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3. Scores are summed to reveal a total score ranging between 0 and 21 with higher scores indicating higher symptomatology [50].

- Activity levels were assessed using the Godin Sheppard Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (GSLTPAQ) [51]. This scale uses the metabolic equivalent of a task (METS) and is calculated by (Strenuous activity × 9 METS) + (moderate exercise × 5 METS) + (light exercise × 3 METS) = total leisure activity score [51]. Scores can then be categorized into insufficiently active (scores < 14), moderately active (scores 14–23), and active (scores > 23) [52].

- Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured using the Six-minute Walk Test (6MWT), which is a cardiorespiratory test that measures the distance someone can walk in six minutes. Greater distances indicate a more favourable health state [40].

- Grip strength was measured by the amount of force applied on a Jamar dynamometer. The amount of force from both hands was combined to create a total score. Increased force indicates a more favourable health state [53].

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

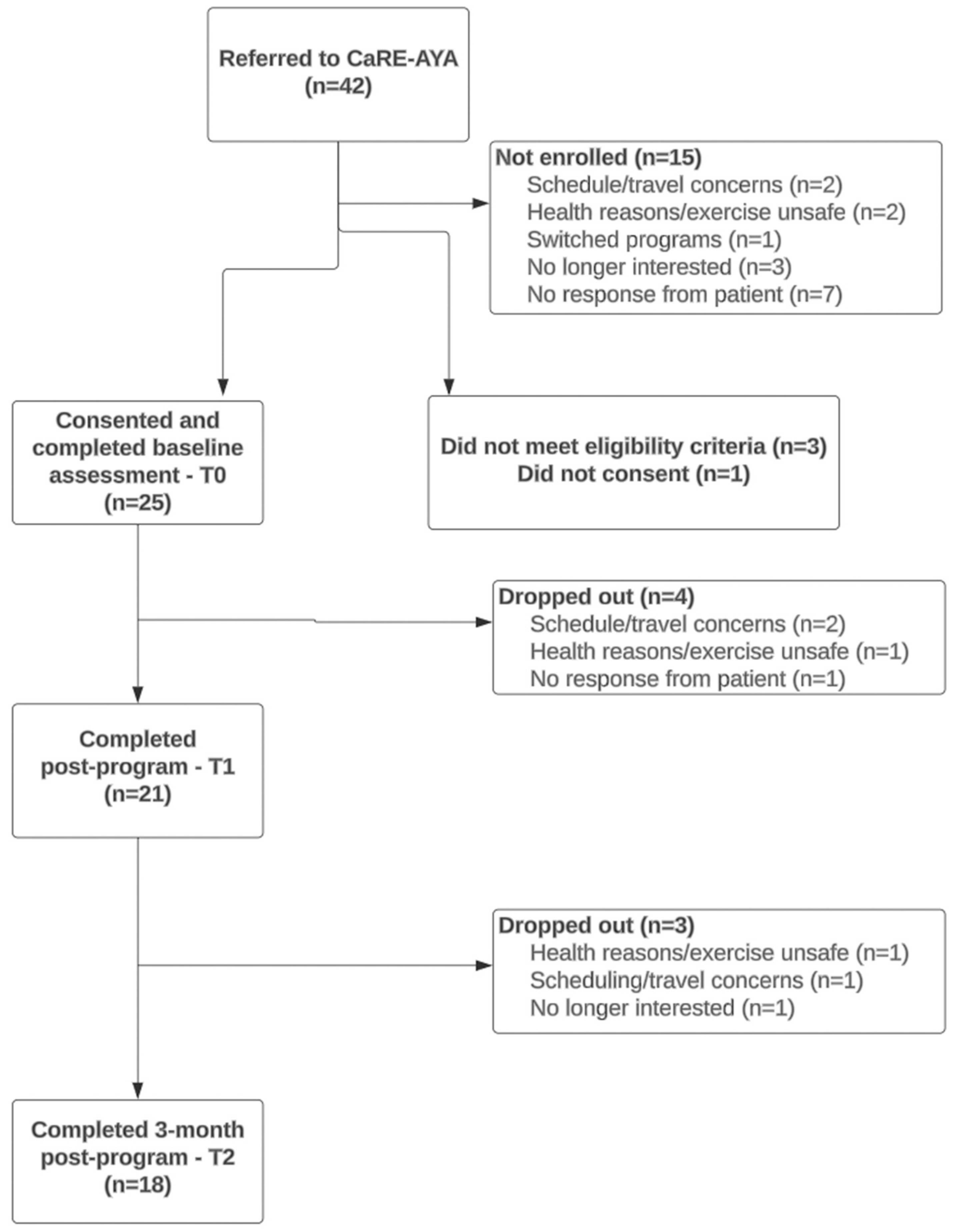

3.1. Feasibility

3.2. Acceptability

3.2.1. Qualitative Interviews

Theme 1: Program Benefits Experienced by CaRE-AYA Participants

Theme 2: Facilitators of the CaRE-AYA Program Benefits

Theme 3: Identified Drawbacks of the CaRE-AYA Program

Theme 4: Barriers to Program Attendance and Participation Faced by CaRE-AYA Participants

3.3. Safety Outcomes

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Canadian Cancer Society, Government of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Canadian Cancer Society, Government of Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2023.

- Nathan, P.C.; Hayes-Lattin, B.; Sisler, J.J.; Hudson, M.M. Critical issues in transition and survivorship for adolescents and young adults with cancers. Cancer 2011, 117, 2335–2341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bleyer, A. Young Adult Oncology: The Patients and Their Survival Challenges. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2007, 57, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi, K.M.; Smith, A.; Schmidt, S.; Keegan, T.H.M.; Zebrack, B.; Lynch, C.F.; Deapen, D.; Shnorhavorian, M.; Tompkins, B.J.; Simon, M.; et al. Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer 2012, 118, 5155–5162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Adolescents & Young Adults with Cancer: A Systems Performance Report; Canadian Partnership Against Cancer: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack, B.J. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer 2011, 117, 2289–2294. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020.

- Hauken, M.A.; Holsen, I.; Fismen, E.; Larsen, T.M.B. Participating in Life Again. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, E48–E59. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, L.; Bøhn, S.K.H.; Lie, H.C.; Fosså, S.D.; Kiserud, C.E. Needs for information about lifestyle and rehabilitation in long-term young adult cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 521–533. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.A.; Papadakos, J.K.; Jones, J.M.; Amin, L.; Chang, E.K.; Korenblum, C.; Mina, D.S.; McCabe, L.; Mitchell, L.; Giuliani, M.E. Reimagining care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs: Moving with the times. Cancer 2016, 122, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, C.; Bhatia, S.; Xu, L.; Cannavale, K.L.; Wong, F.L.; Huang, P.-Y.S.; Cooper, R.; Armenian, S.H. Chronic Comorbidities Among Survivors of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3161–3174. [Google Scholar]

- van Erp, L.M.E.; Maurice-Stam, H.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Tissing, W.J.E.; van der Pal, H.J.H.; Beek, L.; de Vries, A.C.H.; Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.v.D.; Versluys, B.A.B.; Loo, M.v.d.H.-V.d.; et al. Support needs of Dutch young adult childhood cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3291–3302. [Google Scholar]

- Tsangaris, E.; Johnson, J.; Taylor, R.; Fern, L.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; Barr, R.; Fraser, G.; Klassen, A. Identifying the supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: A qualitative analysis and systematic literature review. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 947–959. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S.; Shay, L.A.; King, H.V.; Buckley, J.; Embry, L.; Parsons, H.M. A New Lease on Life: Preliminary Needs Assessment for the Development of a Survivorship Program for Young Adult Survivors of Cancer in South Texas. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 40, e154–e158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magasi, S.; Marshall, H.K.; Winters, C.; Victorson, D. Cancer Survivors’ Disability Experiences and Identities: A Qualitative Exploration to Advance Cancer Equity. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3112. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J.M.; Fitch, M.; Bongard, J.; Maganti, M.; Gupta, A.; D’agostino, N.; Korenblum, C. The Needs and Experiences of Post-Treatment Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeRouen, M.C.; Smith, A.W.; Tao, L.; Bellizzi, K.M.; Lynch, C.F.; Parsons, H.M.; Kent, E.E.; Keegan, T.H.M.; for the AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group. Cancer-related information needs and cancer’s impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Tai, E.; Buchanan, N.; Townsend, J.; Fairley, T.; Moore, A.; Richardson, L.C. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 2012, 118, 4884–4891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mitra, M.; Long-Bellil, L.; Moura, I.; Miles, A.; Kaye, H.S. Advancing Health Equity And Reducing Health Disparities For People With Disabilities In The United States. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation Competency Framework; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Silver, J.K.; Raj, V.S.; Fu, J.B.; Wisotzky, E.M.; Smith, S.R.; Kirch, R.A. Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care: Critical components in the delivery of high-quality oncology services. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 3633–3643. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, J.K.; Baima, J.; Newman, R.; Galantino MLou Shockney, L.D. Cancer rehabilitation may improve function in survivors and decrease the economic burden of cancer to individuals and society. Work 2013, 46, 455–472. [Google Scholar]

- Aagesen, M.; la Cour, K.; Møller, J.J.K.; Stapelfeldt, C.M.; Hauken, M.A.; Pilegaard, M.S. Rehabilitation interventions for young adult cancer survivors: A scoping review. Clin. Rehabil. 2023, 37, 1347. [Google Scholar]

- McGrady, M.E.; Willard, V.W.; Williams, A.M.; Brinkman, T.M. Psychological Outcomes in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 707–716. [Google Scholar]

- Stimler, L.; Campbell, C.; Cover, L.; Pergolotti, M. Current Trends in Occupational Therapy for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors: A Scoping Review. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2022, 37, 664–687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caru, M.; Levesque, A.; Rao, P.; Dandekar, S.; Terry, C.; Brown, V.; McGregor, L.; Schmitz, K. A scoping review to map the evidence of physical activity interventions in post-treatment adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2022, 171, 103620. [Google Scholar]

- Wurz, A.; Brunet, J. Exploring the feasibility and acceptability of a mixed-methods pilot randomized controlled trial testing a 12-week physical activity intervention with adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2019, 5, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Murnane, A.; Thompson, K.; Mancuso, S. ReActivate—A Goal-Orientated Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Rehabil. Oncol. 2019, 37, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, C.; Pinto, B.; Fava, J. Randomized Trial of a Physical Activity and Meditation Intervention for Young Adult Cancer Survivors. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 5, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A.; PAFS Consensus Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C.L.; Taljaard, M.; Lancaster, G.A.; Brehaut, J.C.; Eldridge, S.M. Pilot and feasibility studies for pragmatic trials have unique considerations and areas of uncertainty. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 138, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, C.J.; Santa Mina, D.; Tan, V.; Maganti, M.; Pritlove, C.; Bernstein, L.J.; Langelier, D.M.; Chang, E.; Jones, J.M. CaRE@ELLICSR: Effects of a clinically integrated, group-based, multidimensional cancer rehabilitation program. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e7009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Giraudeau, B.; Caille, A.; Eldridge, S.M.; Weijer, C.; Zwarenstein, M.; Taljaard, M. Heterogeneity in pragmatic randomised trials: Sources and management. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Rengerink, K.O.; Kalkman, S.; Collier, S.; Ciaglia, A.; Worsley, S.D.; Lightbourne, A.; Eckert, L.; Groenwold, R.H.; Grobbee, D.E.; Irving, E.A. Series: Pragmatic trials and real world evidence: Paper 3. Patient selection challenges and consequences. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 89, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mui, H.Z.; Brown-Johnson, C.G.; Saliba-Gustafsson, E.A.; Lessios, A.S.; Verano, M.; Siden, R.; Holdsworth, L.M. Analysis of FRAME data (A-FRAME): An analytic approach to assess the impact of adaptations on health services interventions and evaluations. Learn. Health Syst. 2024, 8, e10364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, J.K.; Baima, J.; Mayer, R.S. Impairment-driven cancer rehabilitation: An essential component of quality care and survivorship. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013, 63, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Winters-Stone, K.M.; Wiskemann, J.; May, A.M.; Schwartz, A.L.; Courneya, K.S.; Zucker, D.S.; Matthews, C.E.; Ligibel, J.A.; Gerber, L.H.; et al. Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culos-Reed, N.; Capozzi, L. Cancer & Exercise Manual for Health and Fitness Professionals, 4th ed.; Assen, K., Ed.; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudry, R. Effect of supervised exercise on aerobic capacity in cancer survivors: Adherence and workload predict variance in effect. World J. Metaanal 2015, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, D.A.; Zagorski, B.; Marzolini, S.; Forhan, M.; Oh, P.I. On-site programmatic attendance to cardiac rehabilitation and the healthy-adherer effect. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2015, 22, 1232–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelier, D.; Jones, J.; Neil-Sztramko, S.; Nadler, M.; Lim, H.; Campbell, K.; Reiman, A.; Greenland, J.; MacKenzie, K.; Bernstein, L.; et al. A Phase II Preference Based, Randomized Controlled Trial of Cancer Rehabilitation (CaRE-AC) for People with Metastatic Breast or Colorectal Cancers [Unpublished Manuscript]. Toronto. Available online: https://simul-europe.com/2024/mascc/Files/1901.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Tam, S.; Kumar, R.; Lopez, P.; Mattsson, J.; Alibhai, S.; Atenafu, E.G.; Bernstein, L.J.; Chang, E.; Clarke, S.; Langelier, D.; et al. A longitudinal multidimensional rehabilitation program for patients undergoing allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation (CaRE-4-alloBMT): Protocol for a phase II feasibility pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courneya, K.S.; Segal, R.J.; Mackey, J.R.; Gelmon, K.; Reid, R.D.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Ladha, A.B.; Proulx, C.; Vallance, J.K.; Lane, K.; et al. Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise in Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Adjuvant Chemotherapy: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4396–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Ustun, T.; Kostanjsek, N.; Chatterji, S.; Rehm, J. Measuring Health and Disability; WHO Press, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J.E.; Snow, K.; Kosinski, M.; Gandek, B. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide; The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre Hospitals: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.; Smith, A.B.; Keding, A.; Velikova, G. The Social Difficulties Inventory (SDI): Development of subscales and scoring guidance for staff. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard leisure-time physical activity questionnaire. Health Fit. J. 2011, 4, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Amireault, S.; Godin, G. The Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire: Validity Evidence Supporting its Use for Classifying Healthy Adults into Active and Insufficiently Active Categories. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2015, 120, 604–622. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, G.F.; McDonald, C.; Chenier, T.C. Measurement of Grip Strength: Validity and Reliability of the Sphygmomanometer and Jamar Grip Dynamometer. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1992, 16, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Billingham, S.A.; Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, J.A.; Yu, X.; Stewart, A.L.; Hays, R.D. Guidelines for Designing and Evaluating Feasibility Pilot Studies. Med. Care 2022, 60, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totton, N.; Lin, J.; Julious, S.; Chowdhury, M.; Brand, A. A Review of Sample Sizes for UK Pilot and Feasibility Studies on the ISRCTN Registry from 2013 to 2020. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, E.; Weisner, T. Dedoose. 2023. Available online: https://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Guest, G.; MacQueen, K.; Namey, E. Applied Thematic Analysis; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social. Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.; Hume, P.A.; Maxwell, L. Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J.; Lopian, L.; Le, B.; Edney, S.; Van Kessel, G.; Plotnikoff, R.; Vandelanotte, C.; Olds, T.; Maher, C. It’s not raining men: A mixed-methods study investigating methods of improving male recruitment to health behaviour research. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, D.J.; Haritopoulou-Sinanidou, M.; Gabrovska, P.; Tseng, H.-W.; Honeyman, D.; Schweitzer, D.; Rae, K.M. Barriers and facilitators for recruiting and retaining male participants into longitudinal health research: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2024, 24, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith, A.A.; Woodyatt, C.; Sineath, R.C.; Hunkeler, E.M.; Barnwell, L.T.; Graham, A.; Stephenson, R.; Goodman, M. Perceptions of Barriers to and Facilitators of Participation in Health Research Among Transgender People. Transgend Health 2016, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, A.M.; Chafranskaia, A.; Lopez, C.J.; Maganti, M.; Bernstein, L.J.; Chang, E.; Langelier, D.M.; Obadia, M.; Edwards, B.; Oh, P.; et al. CaRE @ Home: Pilot Study of an Online Multidimensional Cancer Rehabilitation and Exercise Program for Cancer Survivors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, C.; Qi, S.; Thompson, S.; DeIure, A.; McKillop, S.; Watson, L. Understanding the Symptoms and Concerns of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer in Alberta: A Comparative Cohort Study Using Patient-Reported Outcomes. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2023, 12, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Xie, M.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, J.-E.; Cheng, A.S.K. Effects of Exercise Intervention on Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients and Survivors: A Meta-Analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 153473541989559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, C.M. A scoping review of literature: What has been studied about adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer? Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 27, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total Participants (n = 25) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 32.8 (4.8) |

| Median (range) | 34.0 (20–39) |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | |

| Mean (SD) | 20.7 (19.0) |

| Median (range) | 13.9 (3.1–84.3) |

| Diagnosis n (%) | |

| Hematological disease site | 11 (44) |

| Breast disease site | 8 (32) |

| Gynaecologic disease site | 2 (8) |

| CNS disease site | 1 (4) |

| Gastrointestinal disease site | 1 (4) |

| Head and neck disease site | 1 (4) |

| Sarcoma disease site | 1 (4) |

| Sex n (%) | |

| Female | 19 (76) |

| Male | 6 (24) |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Female | 18 (72) |

| Male | 6 (24) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (4) |

| On active treatment n (%) | |

| No | 19 (76) |

| Yes | 6 (24) |

| Treatment received n (%) | |

| Systemic treatment | 21 (84) |

| Surgical treatment | 13 (52) |

| Radiation therapy | 13 (52) |

| Other | 5 (20) |

| Ethnicity n (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 8 (32) |

| East Asian | 4 (16) |

| South Asian | 3 (12) |

| Other | 3 (12) |

| Latin American | 2 (8) |

| Southeast Asian | 2 (8) |

| West Asian | 2 (8) |

| Arab | 1 (4) |

| Marital status n (%) | |

| Single, never married | 14 (56) |

| Married/common law | 10 (40) |

| Divorced/separated | 1 (4) |

| Highest level of education completed n (%) | |

| Completed college/university | 11 (44) |

| Post-graduate degree | 5 (20) |

| Completed high school | 3 (12) |

| Professional degree | 3 (12) |

| Less than high school | 1 (4) |

| Completed technical school | 1 (4) |

| Other | 1 (4) |

| Employment n (%) a | |

| On disability/sick leave | 8 (33) |

| Full time | 6 (25) |

| Unemployed | 4 (17) |

| Part-time | 3 (13) |

| Other | 3 (13) |

| Living arrangement n (%) | |

| Spouse/partner | 12 (48) |

| Alone | 6 (24) |

| Other family/friend | 5 (20) |

| Other | 2 (8) |

| Socioeconomic status n (%) b | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 (33) |

| USD 40,000–$75,000 | 5 (21) |

| <USD 20,000 | 5 (21) |

| >USD 75,000 | 4 (17) |

| USD 20,000–USD 39,000 | 2 (8) |

| Reason for referral c | |

| Deconditioning | 15 (60) |

| Pain | 12 (48) |

| Cancer-related fatigue | 10 (40) |

| Limitations to mobility | 9 (36) |

| Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy | 7 (28) |

| Neurocognitive impairments | 7 (28) |

| Lymphedema | 3 (12) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corke, L.; Langelier, D.M.; Gupta, A.A.; Capozza, S.; Antonen, E.; Trepanier, G.; Avery, L.; Lopez, C.; Edwards, B.; Jones, J.M. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Multicomponent Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2025, 17, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071066

Corke L, Langelier DM, Gupta AA, Capozza S, Antonen E, Trepanier G, Avery L, Lopez C, Edwards B, Jones JM. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Multicomponent Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivors. Cancers. 2025; 17(7):1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071066

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorke, Lauren, David M. Langelier, Abha A. Gupta, Scott Capozza, Eric Antonen, Gabrielle Trepanier, Lisa Avery, Christian Lopez, Beth Edwards, and Jennifer M. Jones. 2025. "A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Multicomponent Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivors" Cancers 17, no. 7: 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071066

APA StyleCorke, L., Langelier, D. M., Gupta, A. A., Capozza, S., Antonen, E., Trepanier, G., Avery, L., Lopez, C., Edwards, B., & Jones, J. M. (2025). A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Feasibility and Acceptability of a Tailored Multicomponent Rehabilitation Program for Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Survivors. Cancers, 17(7), 1066. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071066