Split-Dose Cisplatin Use, Eligibility Criteria, and Drivers for Treatment Choice in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Large International Physician Survey

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Physician Demographics and Characteristics

3.2. Use of Split-Dose Cisplatin in UC and la/mUC

3.3. Physician Characteristics Influencing Prescribing Behavior for Split-Dose Cisplatin

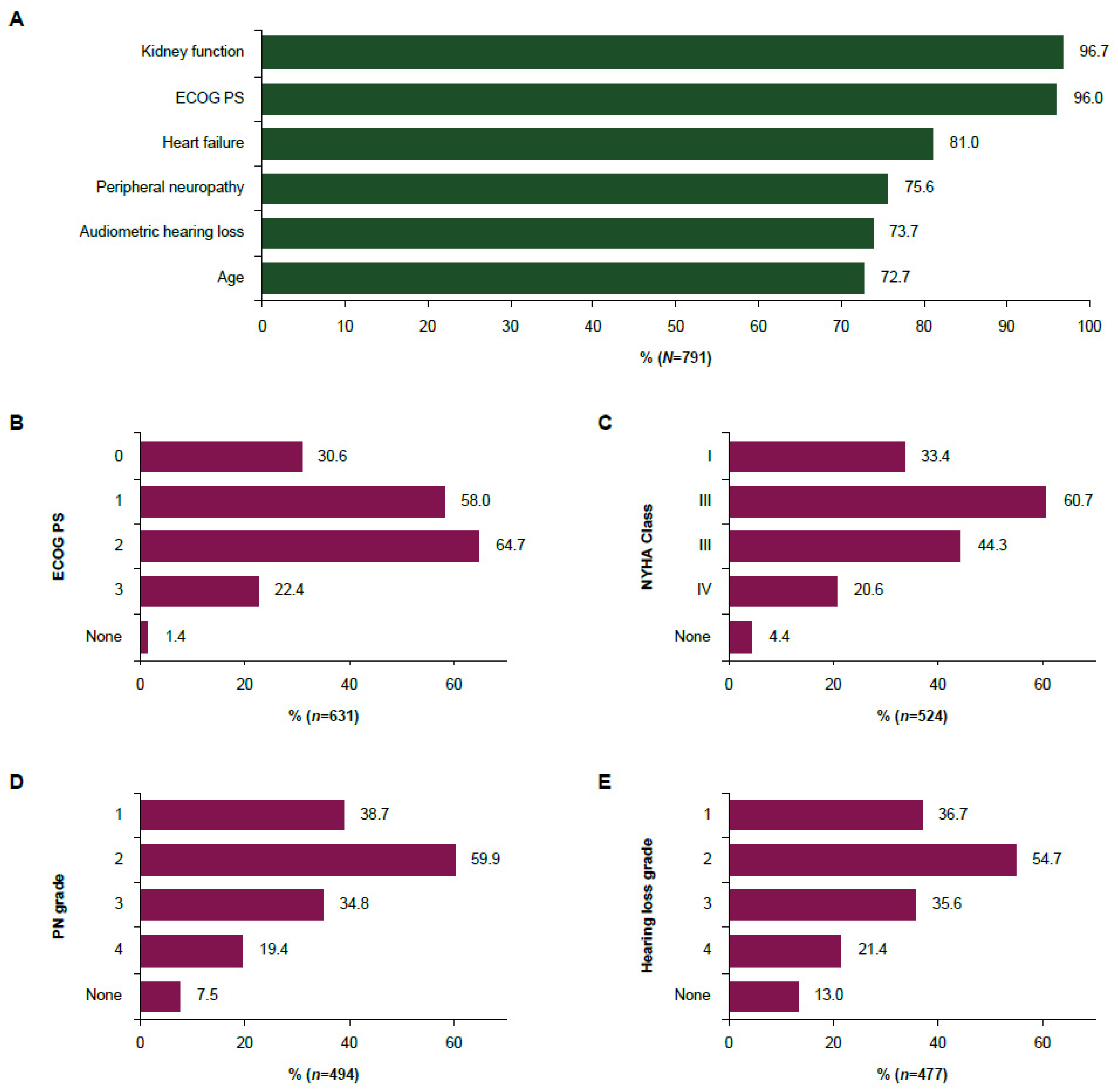

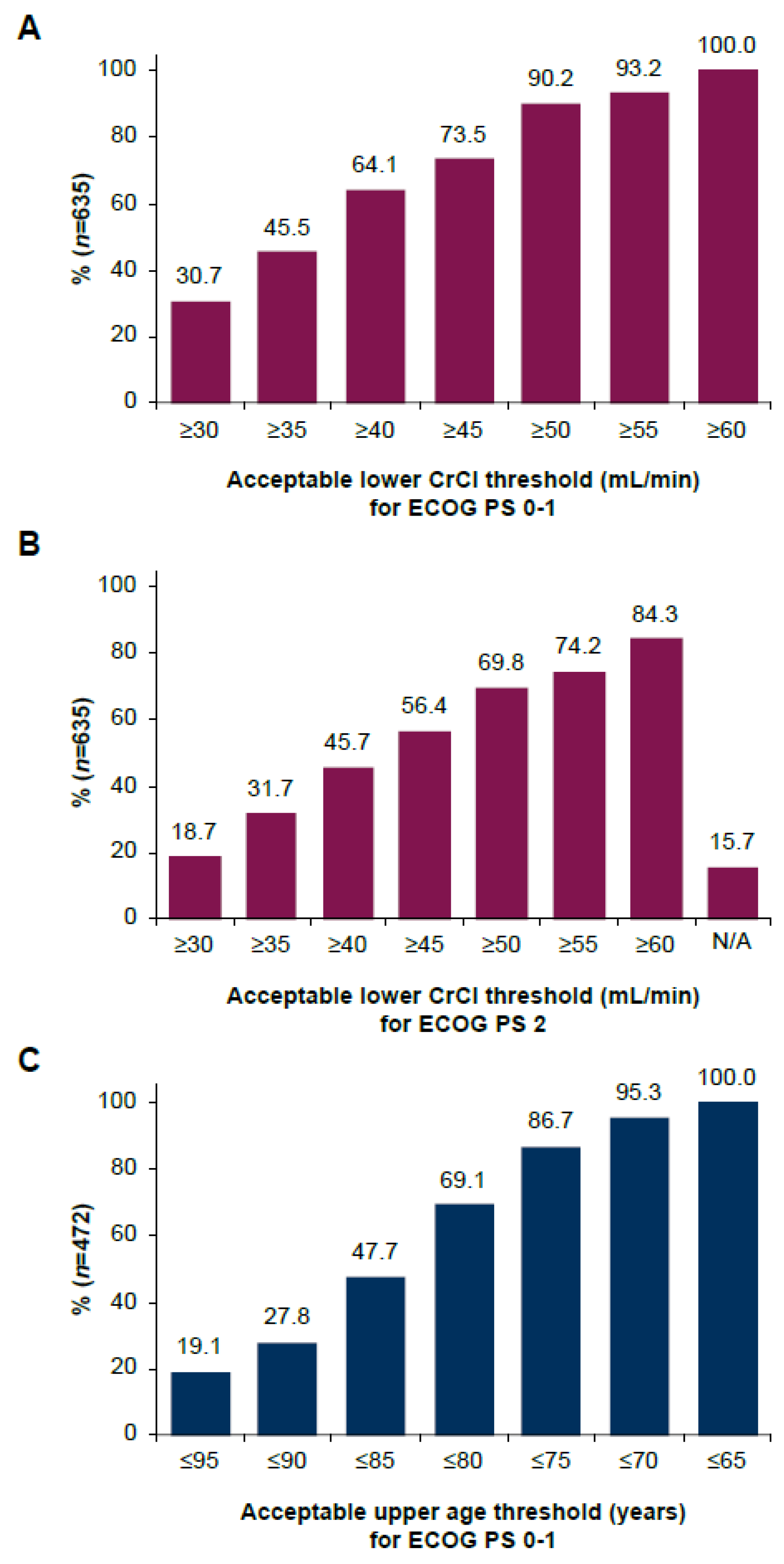

3.4. Eligibility Criteria and Thresholds for the Use of Split-Dose Cisplatin in la/mUC

3.5. Treatment Preferences for la/mUC with Borderline Kidney Function

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Jones, R.J.; Crabb, S.J.; Linch, M.; Birtle, A.J.; McGrane, J.; Enting, D.; Stevenson, R.; Liu, K.; Kularatne, B.; Hussain, S.A. Systemic anticancer therapy for urothelial carcinoma: UK oncologists’ perspective. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathomas, R.; Lorch, A.; Bruins, H.M.; Compérat, E.M.; Cowan, N.C.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Fietkau, R.; Gakis, G.; Hernández, V.; Espinós, E.L.; et al. The 2021 Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines on metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2021, 81, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines; Presented at the EAU Annual Congress, Paris, 2024; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 978-94-92671-23-3. [Google Scholar]

- Powles, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Comperat, E.; De Santis, M.; Huddart, R.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Valderrama, B.; Ravaud, A.; Shariat, S.; et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 33, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Bellmunt, J.; Comperat, E.; De Santis, M.; Huddart, R.; Loriot, Y.; Necchi, A.; Valderrama, B.; Ravaud, A.; Shariat, S.; et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline interim update on first-line therapy in advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Bladder Cancer; v6.2024; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Powles, T.; Park, S.H.; Voog, E.; Caserta, C.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gurney, H.; Kalofonos, H.; Radulović, S.; Demey, W.; Ullén, A.; et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, M.S.; Sonpavde, G.; Powles, T.; Necchi, A.; Burotto, M.; Schenker, M.; Sade, J.P.; Bamias, A.; Beuzeboc, P.; Bedke, J.; et al. Nivolumab plus gemcitabine–cisplatin in advanced urothelial carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1778–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, W.A.; Seo, H.K. Optimizing frontline therapy in advanced urothelial cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Hahn, N.M.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Sonpavde, G.; Hutson, T.; Oh, W.K.; Dreicer, R.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Sternberg, C.N.; Bajorin, D.F.; et al. Treatment of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer “unfit” for cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Chen, G.J.; Oh, W.K.; Bellmunt, J.; Roth, B.J.; Petrioli, R.; Dogliotti, L.; Dreicer, R.; Sonpavde, G. Comparative effectiveness of cisplatin-based and carboplatin-based chemotherapy for treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2011, 23, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, R.; Musat, M.G.; Gulas, I.; Hubscher, E.; Moradian, H.; Guenther, S.; Kearney, M.; Sridhar, S.S. Split-dose cisplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2024, 22, 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlack, K.; Kubin, T.; Ruhnke, M.; Schulte, C.; Machtens, S.; Eisen, A.; Osowski, U.; Guenther, S.; Kearney, M.; Lipp, R.; et al. Split-dose cisplatin plus gemcitabine use and associated clinical outcomes in the first-line (1L) treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer (la/mUC): Results of a retrospective observational study in Germany (CONVINCE). Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Lee, J.L.; You, D.; Jeong, I.G.; Song, C.; Hong, B.; Hong, J.H.; Ahn, H. Gemcitabine plus split-dose cisplatin could be a promising alternative to gemcitabine plus carboplatin for cisplatin-unfit patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, B.L.; Agarwal, N.; Hussain, S.A.; Boucher, K.M.; Von Der Maase, H.; Kaufman, D.S.; Lorusso, V.; Moore, M.J.; Galsky, M.D.; Sonpavde, G. Pooled analysis of phase II trials evaluating weekly or conventional cisplatin as first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2013, 11, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, A.; Shiroma, Y.; Iwata, M.; Nakamura, M.; Torii-Goto, A.; Hida, H.; Tanaka, N.; Miyazaki, M.; Yamada, K.; Noda, Y. Survey of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 15, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.M.; Gupta, S.; Kitchlu, A.; Meraz-Munoz, A.; North, S.A.; Alimohamed, N.S.; Blais, N.; Sridhar, S.S. Defining cisplatin eligibility in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Hussain, S.A.; Stocken, D.D.; Riley, P.; Palmer, D.H.; Peake, D.R.; Geh, J.I.; Spooner, D.; James, N.D. A phase I/II study of gemcitabine and fractionated cisplatin in an outpatient setting using a 21-day schedule in patients with advanced and metastatic bladder cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Barrera, R.; Bellmunt, J.; Suárez, C.; Valverde, C.; Guix, M.; Serrano, C.; Gallén, M.; Carles, J. Cisplatin and gemcitabine administered every two weeks in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma and impaired renal function. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, L.; Flechon, A.; Tosi, D.; Abadie Lacourtoisie, S.; Joly, F.; Guillot, A.; Loriot, Y.; Dauba, J.; Roubaud, G.; Rolland, F.; et al. Vefora, GETUG-AFU V06 study: Randomized multicenter phase II/III trial of fractionated cisplatin (CI)/gemcitabine (G) or carboplatin (CA)/g in patients (pts) with advanced urothelial cancer (UC) with impaired renal function (IRF)—Results of a planned interim analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38 (Suppl. 6), 461. [Google Scholar]

- De Valasco Oria, G.A.; García-Carbonero, I.; Esteban-Gonzalez, E.; Pinto, A.; Lorente, D.; de Liaño, A.G.; Ortega, E.M.; Colomo, L.J.; Puente, J.; Gonzalez, I.; et al. Atezolizumab (ATZ) with split-doses of cisplatin plus gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (SOGUG-AUREA): A multicentre, single-arm phase II trial. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, S1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Yaegashi, H.; Shigehara, K.; Nohara, T.; Kadono, Y.; Mizokami, A. Gemcitabine plus cisplatin split versus gemcitabine plus carboplatin for advanced urothelial cancer with cisplatin-unfit renal function. In Vivo 2018, 33, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milloy, N.; Kirker, M.; Unsworth, M.; Montgomery, R.; Kluth, C.; Kearney, M.; Chang, J. Real-world analysis of treatment patterns and platinum-based treatment eligibility of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer in 5 European countries. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2023, 22, e136–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Bellmunt, J.; Plimack, E.R.; Sonpavde, G.P.; Grivas, P.; Apolo, A.B.; Pal, S.K.; Siefker-Radtke, A.O.; Flaig, T.W.; Galsky, M.D.; et al. Defining “platinum-ineligible” patients with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40 (Suppl. 6), 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Ma, E.; Shah-Manek, B.; Mills, R.; Ha, L.; Krebsbach, C.; Blouin, E.; Tayama, D.; Ogale, S. Cisplatin ineligibility for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A survey of clinical practice perspectives among US oncologists. Bladder Cancer 2019, 5, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Powles, T.; Kearney, M.; Panattoni, L.; Land, N.; Flottemesch, T.; Sullivan, P.; Kirker, M.; Bharmal, M.; Guenther, S.; et al. Age and other criteria influencing nontreatment of patients (pts) with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (la/mUC): Results of a physician survey in five European countries (Eu5). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. 16), 4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmunt, J.; Mottet, N.; De Santis, M. Urothelial carcinoma management in elderly or unfit patients. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2016, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, U.M.; Testi, I.; De Santis, M. Front-line platinum continues to have a role in advanced bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. Focus 2024, 10, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galsky, M.D.; Guan, X.; Rishipathak, D.; Rapaport, A.S.; Shehata, H.M.; Banchereau, R.; Yuen, K.; Varfolomeev, E.; Hu, R.; Han, C.J.; et al. Immunomodulatory effects and improved outcomes with cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy plus atezolizumab in urothelial cancer. Cell. Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, E.; Arranz, J.Á.; De Santis, M.; Bamias, A.; Kikuchi, E.; Del Muro, X.G.; Park, S.H.; De Giorgi, U.; Alekseev, B.; Mencinger, M.; et al. Atezolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy in untreated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor130): Final overall survival analysis results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Valderrama, B.P.; Gupta, S.; Bedke, J.; Kikuchi, E.; Hoffman-Censits, J.; Iyer, G.; Vulsteke, C.; Park, S.H.; Shin, S.J.; et al. Enfortumab vedotin and pembrolizumab in untreated advanced urothelial cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, C.; Lopes, G.d.L.; Yusof, M.M.; Rubagumya, F.; Rutkowski, P.; Sengar, M. Barriers in access to oncology drugs—A global crisis. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 20, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Polimera, H.; Krupski, T.; Necchi, A. Geography should not be an “oncologic destiny” for urothelial cancer: Improving access to care by removing local, regional, and international barriers. In American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book; American Society of Clinical Oncology: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022; Volume 42, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, G.D.L., Jr.; de Souza, J.A.; Barrios, C. Access to cancer medications in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powles, T.; Catto, J.W.; Galsky, M.D.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Meeks, J.J.; Nishiyama, H.; Vu, T.Q.; Antonuzzo, L.; Wiechno, P.; Atduev, V.; et al. Perioperative durvalumab with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in operable bladder cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J.A.; Yip, W.; Wong, N.C.; Sjoberg, D.D.; Bochner, B.H.; Dalbagni, G.; Donat, S.M.; Herr, H.W.; Cha, E.K.; Donahue, T.F.; et al. Multicenter phase II clinical trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with high-grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.A.; Palmer, D.H.; Lloyd, B.; Collins, S.I.; Barton, D.; Ansari, J.; James, N.D. A study of split-dose cisplatin-based neo-adjuvant chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 3, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Europe a | North America b | Brazil | India | Australia | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 791 | n = 375 | n = 184 | n = 100 | n = 107 | n = 25 | ||

| Age, years | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.2 (9.3) | 44.4 (9.1) | 45.0 (10.7) | 39.2 (6.7) | 39.7 (7.4) | 43.5 (9.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 41 (36–50) | 44 (37–51) | 45 (38–53) | 38 (35–42) | 39 (35–42) | 40 (35–50) | |

| Years in clinical practice c | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 13.2 (7.3) | 14.1 (6.9) | 14.7 (7.8) | 9.8 (5.7) | 10.8 (6.9) | 10.9 (7.9) | |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (7–18) | 14 (8–19) | 14 (8–20) | 8 (6–12) | 9 (7–14) | 8 (4–16) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.001 | ||||||

| Female | 210 (26.5) | 110 (29.3) | 32 (17.4) | 46 (46.0) | 16 (15.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Male | 578 (73.1) | 264 (70.4) | 151 (82.1) | 54 (54.0) | 91 (85.0) | 18 (72.0) | |

| Other | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Medical specialty, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Medical oncologist | 725 (91.7) | 325 (86.7) | 184 (100) | 100 (100) | 91 (85.0) | 25 (100) | |

| Urologist | 66 (8.3) | 50 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (15.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Practice setting, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Private | 271 (34.3) | 30 (8.0) | 61 (33.2) | 88 (88.0) | 90 (84.1) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Public | 436 (55.1) | 314 (83.7) | 92 (50.0) | 4 (4.0) | 13 (12.1) | 13 (52.0) | |

| I spend equal time in either setting | 84 (10.6) | 31 (8.3) | 31 (16.8) | 8 (8.0) | 4 (3.7) | 10 (40.0) | |

| Principal practice location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Academic/teaching hospital or specialized cancer center | 465 (58.8) | 255 (68.0) | 103 (56.0) | 44 (44.0) | 42 (39.3) | 21 (84.0) | |

| Community/nonteaching hospital | 212 (26.8) | 89 (23.7) | 51 (27.7) | 6 (6.0) | 64 (59.8) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Office-based practice | 114 (14.4) | 31 (8.3) | 30 (16.3) | 50 (50.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Hospital/center size, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Large (≥500 beds) | 404 (51.1) | 235 (62.7) | 92 (50.0) | 22 (22.0) | 40 (37.4) | 15 (60.0) | |

| Medium (100–499 beds) | 231 (29.2) | 97 (25.9) | 56 (30.4) | 26 (26.0) | 46 (43.0) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Small (<100 beds) | 36 (4.6) | 7 (1.9) | 6 (3.3) | 2 (2.0) | 19 (17.8) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Don’t know/unsure | 6 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| NA (office-based practice) | 114 (14.4) | 31 (8.3) | 30 (16.3) | 50 (50.0) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Number of monthly new (first-time) patients with UC | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 24.9 (44.8) | 24.9 (44.8) | 32.0 (52.8) | 27.8 (45.6) | 11.7 (15.1) | 11.7 (25.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (5–28) | 10 (5–28) | 16 (10–35) | 12 (5–30) | 6 (4–15) | 5 (3–10) | |

| Number of monthly new (first-time) and follow-up patients with UC | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.0 (59.2) | 51.6 (66.3) | 47.1 (65.8) | 23.3 (23.8) | 21.4 (34.9) | 23.7 (30.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (12–50) | 30 (20–60) | 25 (15–50) | 15 (10–26) | 10 (6–23) | 10 (8–20) | |

| Number of monthly new (first time) patients with la/mUC treated | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 28.5 (44.5) | 35.3 (49.3) | 33.4 (52.7) | 16.2 (18.1) | 10.7 (16.6) | 14.8 (17.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (8–30) | 20 (10–40) | 18 (10–30) | 10 (5–20) | 5 (3–10) | 8 (4–15) | |

| Enrollment of patients with UC in clinical trials, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 395 (49.9) | 211 (56.3) | 92 (50.0) | 47 (47.0) | 26 (24.3) | 19 (76.0) | |

| No | 396 (50.1) | 164 (43.7) | 92 (50.0) | 53 (53.0) | 81 (75.7) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Guidelines considered for the treatment of UC, n (%) d | |||||||

| EAU | 271 (34.3) | 184 (49.1) | 26 (14.1) | 22 (22.0) | 33 (30.8) | 6 (24.0) | <0.001 |

| ESMO | 476 (60.2) | 302 (80.5) | 45 (24.5) | 72 (72.0) | 39 (36.4) | 18 (72.0) | <0.001 |

| NCCN | 490 (61.9) | 152 (40.5) | 154 (83.7) | 80 (80.0) | 85 (79.4) | 19 (76.0) | <0.001 |

| AUA/SUO | 115 (14.5) | 52 (13.9) | 38 (20.7) | 11 (11.0) | 11 (10.3) | 3 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| ASCO | 381 (48.2) | 156 (41.6) | 110 (59.8) | 81 (81.0) | 20 (18.7) | 14 (56.0) | <0.001 |

| National guideline(s) | 143 (18.1) | 103 (27.5) | 6 (3.3) | 26 (26.0) | 4 (3.7) | 4 (16.0) | 0.0665 |

| Other international guideline(s) | 6 (0.8) | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0.1344 |

| Institutional guideline(s) | 100 (12.6) | 53 (14.1) | 16 (8.7) | 14 (14.0) | 11 (10.3) | 6 (24.0) | 0.4008 |

| None e | 11 (1.4) | 7 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.7491 |

| Method to assess kidney function in patients with UC being considered for platinum-based chemotherapy, n (%) d | <0.001 | ||||||

| Calculated creatinine clearance | 680 (86.0) | 337 (89.9) | 149 (81.0) | 90 (90.0) | 81 (75.7) | 23 (92.0) | |

| Measured creatinine clearance | 196 (24.8) | 106 (28.3) | 58 (31.5) | 20 (20.0) | 10 (9.3) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Measured GFR | 251 (31.7) | 141 (37.6) | 75 (40.8) | 17 (17.0) | 12 (11.2) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Serum creatinine value | 338 (42.7) | 155 (41.3) | 96 (52.2) | 40 (40.0) | 42 (39.3) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Other | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Formula used to calculate creatinine clearance, n (%) f | n = 680 | n = 337 | n = 149 | n = 90 | n = 81 | n = 23 | |

| Cockcroft-Gault equation | 462 (67.9) | 202 (59.9) | 108 (72.5) | 62 (68.9) | 72 (88.9) | 18 (78.3) | 0.002 |

| Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation | 82 (12.1) | 56 (16.6) | 9 (6.0) | 11 (12.2) | 5 (6.2) | 1 (4.3) | |

| Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation | 99 (14.6) | 52 (15.4) | 25 (16.8) | 16 (17.8) | 2 (2.5) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Jelliffe equation | 4 (0.6) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Wright equation | 6 (0.9) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Unsure | 24 (3.5) | 19 (5.6) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Prescribes split-dose cisplatin (any setting), n (%) | 670 (84.7) | 334 (89.1) | 168 (91.3) | 67 (67.0) | 82 (76.6) | 19 (76.0) | <0.001 |

| n = 670 g | n = 334 | n = 168 | n = 67 | n = 82 | n = 19 | ||

| Percentage of patients treated with split-dose cisplatin in the neoadjuvant setting | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 40.9 (26.3) | 34.7 (22.5) | 39.0 (22.4) | 70.0 (25.5) | 49.0 (30.1) | 27.8 (28.3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 34 (20–56) | 30 (20–50) | 35 (20–50) | 70 (50–98) | 50 (20–75) | 20 (10–32) | |

| Percentage of patients treated with split-dose cisplatin in the adjuvant setting | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 39.5 (26.0) | 34.4 (22.4) | 37.8 (22.7) | 64.4 (27.8) | 47.3 (31.1) | 21.7 (21.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 35 (20–54) | 30 (20–50) | 35 (20–50) | 65 (50–83) | 50 (20–75) | 20 (8–20) | |

| Percentage of patients treated with split-dose cisplatin in the advanced setting | <0.001 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 43.0 (26.8) | 36.8 (22.8) | 40.1 (23.8) | 70.2 (27.9) | 54.4 (30.7) | 33.3 (22.6) | |

| Median (IQR) | 40 (20–60) | 30 (20–50) | 35 (24–51) | 80 (50–100) | 50 (30–80) | 33 (15–48) |

| Total N = 660 | USA n = 135 | India n = 81 | Brazil n = 67 | Germany n = 67 | France n = 70 | UK n = 60 | Italy n = 69 | Spain n = 64 | Canada n = 29 | Australia n = 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within the unresectable locally advanced or metastatic setting, in which line(s) of treatment do you consider using split-dose cisplatin? (multiple answers possible) | |||||||||||

| 1L | 548 (83.0) | 102 (75.6) | 62 (76.5) | 64 (95.5) | 55 (82.1) | 62 (88.6) | 51 (85.0) | 61 (88.4) | 53 (82.8) | 23 (79.3) | 15 (83.3) |

| 2L | 340 (51.5) | 87 (64.4) | 26 (32.1) | 31 (46.3) | 40 (59.7) | 29 (41.4) | 42 (70.0) | 30 (43.5) | 32 (50.0) | 18 (62.1) | 5 (27.8) |

| 3L | 168 (25.5) | 51 (37.8) | 10 (12.3) | 14 (20.9) | 21 (31.3) | 15 (21.4) | 20 (33.3) | 14 (20.3) | 15 (23.4) | 4 (13.8) | 4 (22.2) |

| Which split-dose cisplatin regimens do you use in patients with la/mUC? (top five regimens; multiple answers possible) | |||||||||||

| GC 35 mg/m2, days 1 + 8 of 21-day cycles | 378 (57.3) | 75 (55.6) | 39 (48.1) | 48 (71.6) | 36 (53.7) | 36 (51.4) | 36 (60.0) | 42 (60.9) | 35 (54.7) | 17 (58.6) | 14 (77.8) |

| GC 25 mg/m2, days 1 + 8 of 21-day cycles | 86 (13.0) | 15 (11.1) | 14 (17.3) | 9 (13.4) | 5 (7.5) | 11 (15.7) | 9 (15.0) | 10 (14.5) | 11 (17.2) | 2 (6.9) | 0 |

| GC 35 mg/m2, days 1 + 8 of 28-day cycles | 36 (5.5) | 7 (5.2) | 6 (7.4) | 0 | 8 (11.9) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (5.0) | 4 (5.8) | 2 (3.1) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (5.6) |

| GC 35 mg/m2, days 1 + 2 of 21-day cycles | 25 (3.8) | 4 (3.0) | 6 (7.4) | 3 (4.5) | 3 (4.5) | 4 (5.7) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (11.1) |

| GC 35 mg/m2, days 1 + 15 of 21-day cycles | 20 (3.0) | 6 (4.4) | 2 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (7.8) | 0 | 0 |

| In patients with la/mUC, do you routinely use avelumab as first-line maintenance if there is no disease progression during or after split-dose cisplatin-based chemotherapy? | |||||||||||

| Yes | 531 (80.5) | 111 (82.2) | 23 (28.4) | 62 (92.5) | 53 (79.1) | 66 (94.3) | 49 (81.7) | 67 (97.1) | 60 (93.8) | 22 (75.9) | 18 (100) |

| No | 129 (19.5) | 24 (17.8) | 58 (71.6) | 5 (7.5) | 14 (20.9) | 4 (5.7) | 11 (18.3) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (6.3) | 7 (24.1) | 0 |

| Covariate | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Model excluding geographic region | ||

| Specialty: oncologist | 1 (ref) | |

| Specialty: urologist | 0.45 (0.24–0.88) | 0.016 |

| Practice years (per decade) | 1.58 (1.18–2.16) | 0.003 |

| Practice setting: private | 1 (ref) | |

| Practice setting: public | 1.94 (1.27–2.97) | 0.002 |

| Practice setting: I spend equal time in either setting | 2.58 (1.21–6.17) | 0.021 |

| Total number of patients with UC per month (per 10 patients) | 1.06 (1.01–1.14) | 0.045 |

| Model including geographic region | ||

| Specialty: oncologist | 1 (ref) | |

| Specialty: urologist | 0.38 (0.19–0.77) | 0.006 |

| Practice years (per decade) | 1.37 (1.01–1.90) | 0.047 |

| Practice setting: private | 1 (ref) | |

| Practice setting: public | 1.12 (0.60–2.09) | 0.713 |

| Practice setting: I spend equal time in either setting | 2.04 (0.88–5.24) | 0.113 |

| Total number of patients with UC per month (per 10 patients) | 1.05 (1.00–1.12) | 0.093 |

| Region: Europe a | 1 (ref) | |

| Region: North America b | 1.11 (0.59–2.20) | 0.748 |

| Region: Brazil | 0.30 (0.14–0.64) | 0.002 |

| Region: India | 0.58 (0.27–1.22) | 0.149 |

| Region: Australia | 0.35 (0.13–1.06) | 0.051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Dwyer, R.; Junker, S.; Szulkin, R.; Kienzle, S.; Kearney, M.; Sridhar, S.S. Split-Dose Cisplatin Use, Eligibility Criteria, and Drivers for Treatment Choice in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Large International Physician Survey. Cancers 2025, 17, 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030509

O’Dwyer R, Junker S, Szulkin R, Kienzle S, Kearney M, Sridhar SS. Split-Dose Cisplatin Use, Eligibility Criteria, and Drivers for Treatment Choice in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Large International Physician Survey. Cancers. 2025; 17(3):509. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030509

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Dwyer, Richard, Sophia Junker, Robert Szulkin, Scarlette Kienzle, Mairead Kearney, and Srikala S. Sridhar. 2025. "Split-Dose Cisplatin Use, Eligibility Criteria, and Drivers for Treatment Choice in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Large International Physician Survey" Cancers 17, no. 3: 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030509

APA StyleO’Dwyer, R., Junker, S., Szulkin, R., Kienzle, S., Kearney, M., & Sridhar, S. S. (2025). Split-Dose Cisplatin Use, Eligibility Criteria, and Drivers for Treatment Choice in Patients with Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma: Results of a Large International Physician Survey. Cancers, 17(3), 509. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17030509