Personality and Family Risk Factors for Poor Mental Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Differentiation of Self

3. Self-Regulation

4. Anxiety

5. Mental Well-Being

6. Goals and Hypotheses

- DoS (emotional reactivity, I-position, emotional cutoff, fusion with others) will be positively associated with mental well-being through the mediation of self-regulation (promotion-focused, prevention-focused) and anxiety.

- a.

- DoS will have an inverse association with prevention and anxiety, and a positive association with promotion and mental well-being.

- b.

- Anxiety will be positively associated with prevention, and negatively associated with promotion and mental well-being.

- c.

- Mental well-being will be positively associated with promotion, and negatively associated with prevention.

7. Method

7.1. Participants

7.2. Instruments

7.3. Procedure

7.4. Data Analysis

8. Results

8.1. Preliminary Analyses

8.2. Mediation Model

9. Discussion

Limitations

10. Contributions

11. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowen, M. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, H.T. How much is enough? Theol. Today 1981, 37, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, M.E.; Bowen, M. Family Evaluation: An Approach Based on Bowen Theory; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman-Barrett, L.; Gross, J.; Conner, T.S.; Benvenuto, M. Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2010, 15, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Tzischinsky, O. The mediating role of emotional distress in the relationship between differentiation of self and the risk of eating disorders among young adults. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O. Bowen theory: A study of differentiation of self and students’ social anxiety and physiological symptoms. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2002, 24, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Peleg, O.; Sarhana, A.; Lam, S.; Haimov, I. Depressive symptoms mediate the relationship between emotional cutoff and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 26, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O. The relationship between type 2 diabetes, differentiation of self, and emotional distress: Jews and Arabs in Israel. Nutrients 2022, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guler, C.V.; Karaca, T. The role of differentiation of self in predicting rumination and emotion regulation difficulties. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2021, 43, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond pleasure and pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory focus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E.T.; Low, M.B. Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 9, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, W.; Tan, Q.; Zhong, Y. People higher in self-control do not necessarily experience more happiness: Regulatory focus also affects subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M.; Diener, E. Approach-avoidance goals and well-being: One size does not fit all. In Handbook of Approach and Avoidance Motivation; Elliot, A.J., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum, Psychology Press: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 24, pp. 415–428. [Google Scholar]

- Manczak, E.; Gietl, C.Z.; McAdams, D. Regulatory focus in the life story: Prevention and promotion as expressed in three layers of personality. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterheld, H.A.; Simpson, J.A. Seeking security or growth: A regulatory focus perspective on motivations in romantic relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 935–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabayashi, H. Self-regulation, marital climate, and emotional well-being among Japanese older couples. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2020, 35, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, S.; Burton, C.; Plaks, J.E. Conservatives anticipate and experience stronger emotional reactions to negative outcomes. J. Personal. 2013, 82, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förster, J.; Grant, H.; Idson, L.C.; Higgins, E.T. Success/failure feedback, expectancies, and approach/avoidance motivation: How regulatory focus moderates classic relations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 37, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Sheldon, K.M. Avoidance achievement motivation: A personal goals analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Thrash, T.M.; Murayama, K. A longitudinal analysis of self-regulation and well-being: Avoidance personal goals, avoidance coping, stress generation, and subjective well-being. J. Personal. 2011, 79, 643–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Sedikides, C.; Murayama, K.; Tanaka, A.; Thrash, T.M.; Mapes, R.R. Cross-cultural generality and specificity in self-regulation: Avoidance personal goals and multiple aspects of well-being in the United States and Japan. Emotion 2012, 12, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, A.A.; Higgins, E.T. Dodging monsters and dancing with dreams: Success and failure at different levels of approach and avoidance. Emot. Rev. 2013, 5, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı-Kabadayı, S.; Öztemel, K. The mediating role of rumination and self-regulation between self-generated stress and psychological well-being. Psychol. Rep. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kring, A.M.; Bachorowski, J.-A. Emotions and psychopathology. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 13, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennin, D.; Farach, F. Emotion and evolving treatments for adult psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2007, 14, 329–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Morris, A. Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, P. Anxiety disorders and GABA neurotransmission: A disturbance of modulation. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolz-del-Castellar, B.; Oliver, J. Relationship between family functioning, differentiation of self and anxiety in Spanish young adults. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O.; Yaniv, I.; Katz, R.; Tzischinsky, O. Does trait anxiety mediate the relationship between differentiation of self and quality of life? Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2018, 46, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.D.; Brito, R.S.; Pereira, C.R. Anxiety associated with COVID-19 and concerns about death: Impacts on psychological well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalbrugge, M.; Pot, A.M.; Jongenelis, L.; Gundy, C.M.; Beekman, A.T.; Eefsting, J.A. The impact of depression and anxiety on well-being, disability and use of health care services in nursing home patients. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.-J. Macro measures of Consumer Well-Being (CWB): A critical analysis and a research agenda. J. Macromarketing 2006, 26, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman ME, P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T. What is well-being? Definition, types, and well-being skills. Want to grow your well-being? Here are the skills you need. Psychology Today. 2019. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/click-here-happiness/201901/what-is-well-being-definition-types-and-well-being-skills (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Helliwell, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, S. Social capital and well-being in times of crisis. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiss, J.T.; Klooster, P.M.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Bohlmeijer, E.T. The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 102, 152189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F.M.; Espigares-López, I.; Brown, T.; Pérez-Mármo, J.M. The relationship between psychological well-being and psychosocial factors in university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moksnes, U.K.; Bjørnsen, H.N.; Eilertsen, M.-E.B.; Espnes, G.A. The role of perceived loneliness and sociodemographic factors in association with subjective mental and physical health and well-being in Norwegian adolescents. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 50, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, E.A.; Friedlander, M. The Differentiation of Self Inventory: Development and initial validation. J. Couns. Psychol. 1998, 28, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowron, E.A.; Schmitt, T.A. Assessing interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI Fusion with Others subscale. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2003, 29, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, O. The relation of differentiation of self and marital satisfaction: What can be learned from married people over the life course? Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2008, 36, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burçin Hocaoğlu, F.; Işık, E. The role of self-construal in the associations between differentiation of self and subjective well-being in emerging adults. Curr. Psychol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.R. A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In Psychology: A Study of a Science. Formulations of the Person and the Social Context; Koch, S., Ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959; Volume 3, pp. 184–256. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R. Dealing with psychological tensions. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1965, 1, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biadsy-Ashkar, A.; Peleg, O. The relationship between differentiation of self and satisfaction with life amongst Israeli women: A cross-cultural perspective. Health 2013, 5, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.; Wachholtz, A. The relationship of anxiety and depression to subjective well-being in a mainland Chinese sample. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Miller, W.R.; Lawendowski, L.A. The self-regulation questionnaire. In Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source Book; VandeCreek, L., Jackson, T.L., Eds.; Professional Resource Press: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1999; pp. 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, M.K.; Tronick, E.Z.; Cohn, J.F.; Olson, K.L. Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, C.C. Relations between social contingency in mother–child interaction and 2-year-olds’ social competence. Dev. Psychol. 1996, 32, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G.; Murray, K.T.; Harlan, E.T. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Waxler, C.; Schmitz, S.; Fulker, D.; Robinson, J.; Emde, R. Behavior problems in 5-year-old monozygotic and dizygotic twins: Genetic and environmental influences, patterns of regulation, and internalization of control. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996, 8, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.A.; Lawrence, E.; Langer, A. Conceptualization and assessment of disengagement in romantic relationships. Pers. Relatsh. 2008, 15, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, E.C.; Kensinger, E.A.; Garcia, S.M.; Ford, J.H.; Cunningham, T.J. With age comes well-being: Older age associated with lower stress, negative affect, and depression throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 26, 2071–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, E.K.; Hofvind, S.; Byberg, L.; Eskild, A. The relation of age at menarche with age at natural menopause: A population study of 336,788 women in Norway. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, J.A. Self-Regulation in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby, L.K.; Bennett, K.M. Marriage and psychological wellbeing: The role of social support. Psychology 2015, 6, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | Min. | Max. | Sk a | K b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation of self | ||||||

| I-position | 4.18 | 0.77 | 1.64 | 6.00 | −0.25 | −0.16 |

| Emotional cutoff | 2.87 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 5.25 | 0.14 | −0.32 |

| Self-regulation | ||||||

| Prevention | 4.86 | 1.78 | 1.00 | 9.00 | −0.01 | −0.56 |

| Promotion | 6.61 | 1.53 | 1.00 | 9.00 | −0.59 | 0.22 |

| Anxiety | 1.72 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.17 | 0.59 |

| Mental well-being | 3.91 | 0.72 | 1.14 | 5.00 | −0.72 | 0.66 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation of self | ||||||

| - | |||||

| −0.26 ** | - | ||||

| Self-regulation | ||||||

| −0.33 ** | 0.50 ** | - | |||

| 0.39 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.17 ** | - | ||

| −0.33 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.28 ** | - | |

| 0.62 ** | −0.41 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.34 ** | - |

| Step I | Step II | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Gender | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Non-Academic Education | 0.01 | 0.08 * |

| Family Status | ||

| Single | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| Married | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Differentiation of self | ||

| I-position | 0.42 *** | |

| Emotional cutoff | −0.20 *** | |

| Self-regulation | ||

| Prevention | −0.07 | |

| Promotion | 0.25 *** | |

| Anxiety | −0.07 | |

| 0.031 * | 0.516 *** | |

| - | 0.485 *** |

| Predicted Variables | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effect | |||||||||

| Prevention | Promotion | Anxiety | Mental Well-Being | Mental Well-Being | ||||||

| Predictors | Beta | p | Beta | p | Beta | p | Beta | p | Beta | 95% CI |

| Demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Gender (Women) | 0.08 | 0.030 | 0.09 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Age | −0.15 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Non-college educated | 0.09 | 0.023 | 0.08 | 0.049 | 0.08 | 0.019 | ||||

| Single | 0.14 | 0.060 | −0.09 | 0.007 | ||||||

| Married | 0.12 | 0.054 | ||||||||

| Differentiation of self | ||||||||||

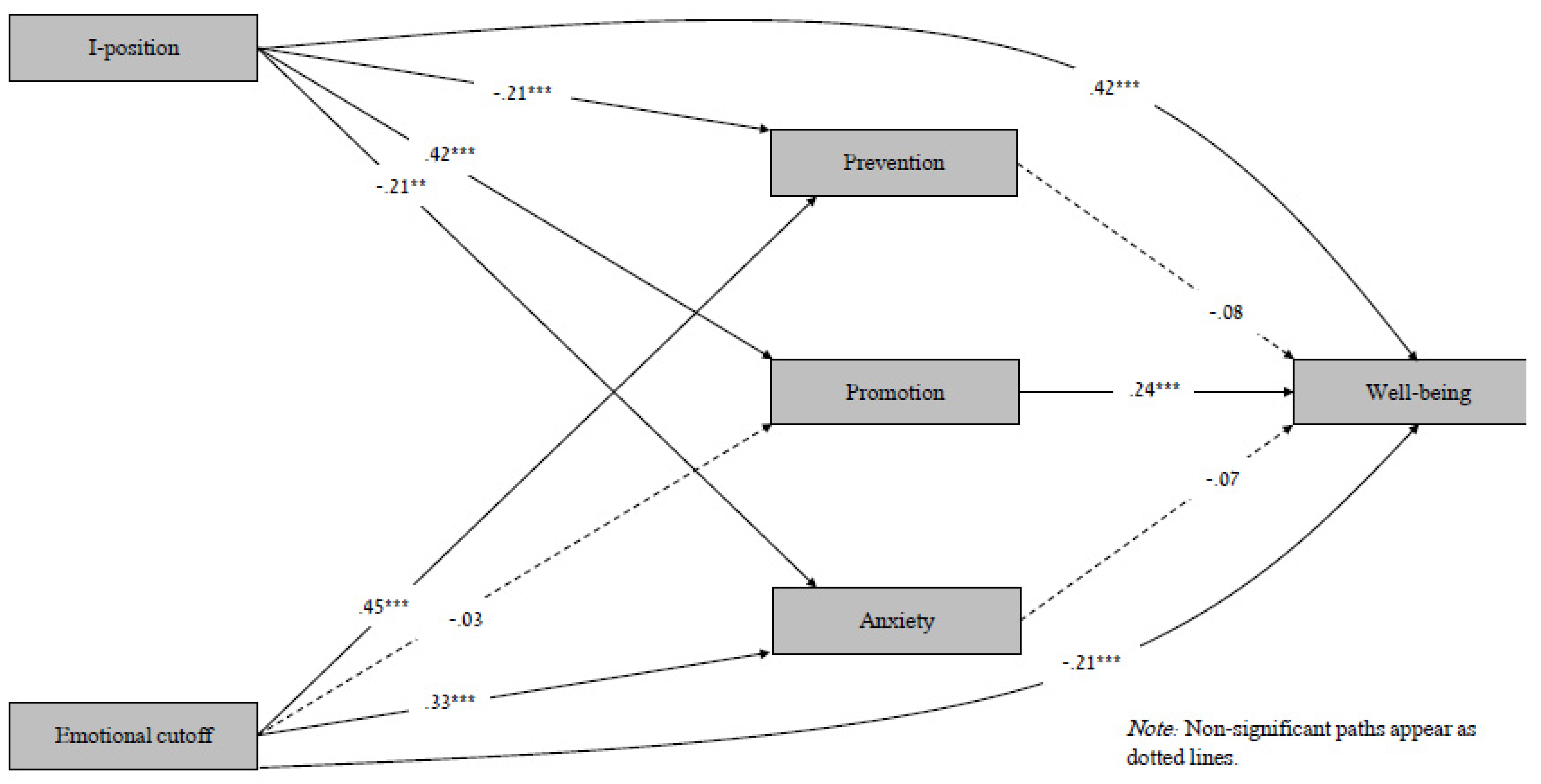

| I-position | −0.21 | <0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 | −0.21 | <0.001 | 0.42 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.07, 0.18 |

| Emotional cutoff | 0.45 | <0.001 | −0.03 | 0.462 | 0.33 | <0.001 | −0.21 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −0.11, −0.02 |

| Self-regulation | ||||||||||

| Prevention | −0.08 | 0.079 | ||||||||

| Promotion | 0.24 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Anxiety | −0.07 | 0.066 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peleg, M.; Peleg, O. Personality and Family Risk Factors for Poor Mental Well-Being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010839

Peleg M, Peleg O. Personality and Family Risk Factors for Poor Mental Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010839

Chicago/Turabian StylePeleg, Maya, and Ora Peleg. 2023. "Personality and Family Risk Factors for Poor Mental Well-Being" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010839

APA StylePeleg, M., & Peleg, O. (2023). Personality and Family Risk Factors for Poor Mental Well-Being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010839