A Cross-Cultural and Trans-Generational Study: Links between Psychological Characteristics and Socio-Political Tendency amongst Urban Population in Afghanistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psycho-Social Factors and Political Behaviour

1.2. Previous and Present Research

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Translation and Linguistic Adaptation of Questionnaires

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Variations

3.2. Between Group Differences

3.3. Associations and Predictive Links

3.4. Intercorrelations between Psycho-Social Variables

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muller, E.N. Seligson, M.A. Civic Culture and Democracy: The Question of Causal Relationships. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 88, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y. Democracy in the ageing society: Quest for political equilibrium between generations. Futures 2017, 85, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.; Rose, P. Understanding Education’s Influence on Support for Democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, D.; Dyson, J. Personality and political orientation. Midwest J. Political Sci. 1968, 12, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatke, M. Personality traits and political ideology: A first global assessment. Political Psychol. 2017, 38, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklikovaska, M. Psychological underpinnings of democracy: Empathy, authoritarianism, self-steem, interpersonal trust, normative identity style, and openness to experience as predictors of support for democracy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, S.D.; de Waal, F.B. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav. Brain Sci. 2002, 25, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboteg-Saric, Z.; Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 2001, 30, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Polycarpou, M.P.; Harmon-Jones, E.; Imhoff, H.J.; Mitchener, E.C.; Bednar, L.L.; Klein, T.R.; Highberger, L. Empathy and attitudes: Can feelings for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward that group? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R.; Gillath, O.; Nitzberg, R.E. Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: Boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 817–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telle, N.; Pfister, H. Not only the miserable receive help: Empathy promotes prosocial behaviour toward the happy. Curr. Psychol. 2012, 31, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, K.A.; Stephan, W.G. Improving Intergroup Relations: The Effects of Empathy on Racial Attitudes. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, H.; Kinman, G. Relationships between psychosocial characteristics and democratic values: A cross-cultural study. Res. Rev. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kaviani, H.; Kinman, G.; Salavati, M. Bicultural Iranians’ political tendency: In between two cultures. J. Soc. 2017, 6, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenberry, G.J.; Dahl, R.A. On Democracy. Foreign Aff. 1999, 78, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffley, M.; Rohrschneider, R. Democratization and political tolerance in seventeen countries: A multi-level model of democratic learning. Political Res. Q. 2003, 56, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Personality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory Perspective; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Norris, P. Rising tide. In Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, R. Personal Relationships Across Cultures; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P.; Inglehart, R. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. The Development of Modes of Moral Thinking and Choice in the Years 10 to 16. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, X. Education and Gender Egalitarianism: The Case of China. Sociol. Educ. 2004, 77, 311–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.I.; Bellman, S.B.; Watson, D.B.; Multidimensional Iowa Suggestibility Scale (MISS). Brief Manual. 2004. Available online: http://www.stonybrookmedicalcenter.org/system/files/MISS_FINAL_BLANK_0.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Guyton, E.M. Critical Thinking and Political Participation: Development and Assessment of a Causal Model. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 1988, 16, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrs, J.C.; Kielmann, S.; Maes, J.; Moschner, B. Effects of right-wing authoritarianism and threat from terrorism on restriction of civil liberties. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2005, 5, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, A.; Soto, C.J.; Inzlicht, M.; Lelkes, Y. Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 106, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Encyclopaedia of Language and Linguistics; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yarshater, E.V.I. Linguistics in South West Asia and North Africa. In Current Trends in Linguistics; Sebeok, T.A., Ed.; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1971; pp. 669–689. [Google Scholar]

- German, F. Language and Ethnicity; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, A.; Afghanistan’s Ethnic Divides. CIDOB Policy Research Project. 2012. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/en/content/download/.../OK_ABUBAKAR%20SIDDIQUE.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2019).

- BPS. Ethical Code of Conduct. 2009. Available online: http://www.bps.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/code_of_ethics_and_conduct.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2014).

- Spreng, R.N.; McKinnon, M.C.; Mar, R.A.; Levine, B. The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. J. Personal. Assess. 2009, 91, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multi- dimensional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, A. Egalitarian sex role attitudes: Scale Development and Comparison of American and Japanese Women. Sex Roles 1991, 24, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrisson, I. Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, T.; Frenkel-Brunswick, E.; Levinson, D.; Sanford, R. The Authoritarian Personality; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Sungur, Z.T. Early modern state formation in Afghanistan in relation to Pashtun Tribalism. Stud. Ethn. Natl. 2016, 6, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R. The ultimate warriors: Why lasting peace will require not just talks with the Taliban, but rescuing the shattered Pashtun culture. Maclean’s 2015, 28, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson, S.; Widmalm, S. Personality and Political Tolerance: Evidence from India and Pakistan. Political Stud. 2016, 64, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hiel, A.; Kossowska, M.; Mervielde, I. The relationship between Openness to Experience and political ideology. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2000, 28, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, R.; Silva, D.R.; Ferreira, A.S. Personality styles and suggestibility: A differential approach. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhrke, A. Reconstruction as modernisation: The ‘post-conflict’ project in Afghanistan. Third World Q. 2007, 28, 1291–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Chang, W.Y. Political participation of teenagers in the information era. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dari Speakers (n = 310) | Pashto Speakers (n = 294) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 165 (53.2%) | 148 (50.3%) |

| Women | 145 (46.8%) | 146 (49.7%) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 35.83 (15.12) | 37.47 (16.27) |

| Generation | ||

| Younger | 158 (51.0%) | 146 (49.7%) |

| Older | 145 (49.0%) | 148 (50.3%) |

| Culture | ||

| Tajik | 104 (33.5%) | 13 (4.5%) |

| Pashtun | 18 (5.8%) | 279 (94.9%) |

| Hazare | 117 (37.5%) | 1 (.3%) |

| Uzbek | 10 (3.2%) | 1 (.3%) |

| Others | 61 (19.7%) | - |

| Education | ||

| High School diploma | 54 (17.4%) | 73 (24.8%) |

| BSc | 236 (76.1%) | 203 (69.1%) |

| MSc and higher | 20 (6.5%) | 18 (6.1%) |

| Group (Dari–Pashto) | Generation (Young, Older) | Group × Generation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empathy | F (1, 604) = 131.36 p < 0.001 | F (1, 604) = 0.08 Ns | F (1, 604) = 0.10 Ns |

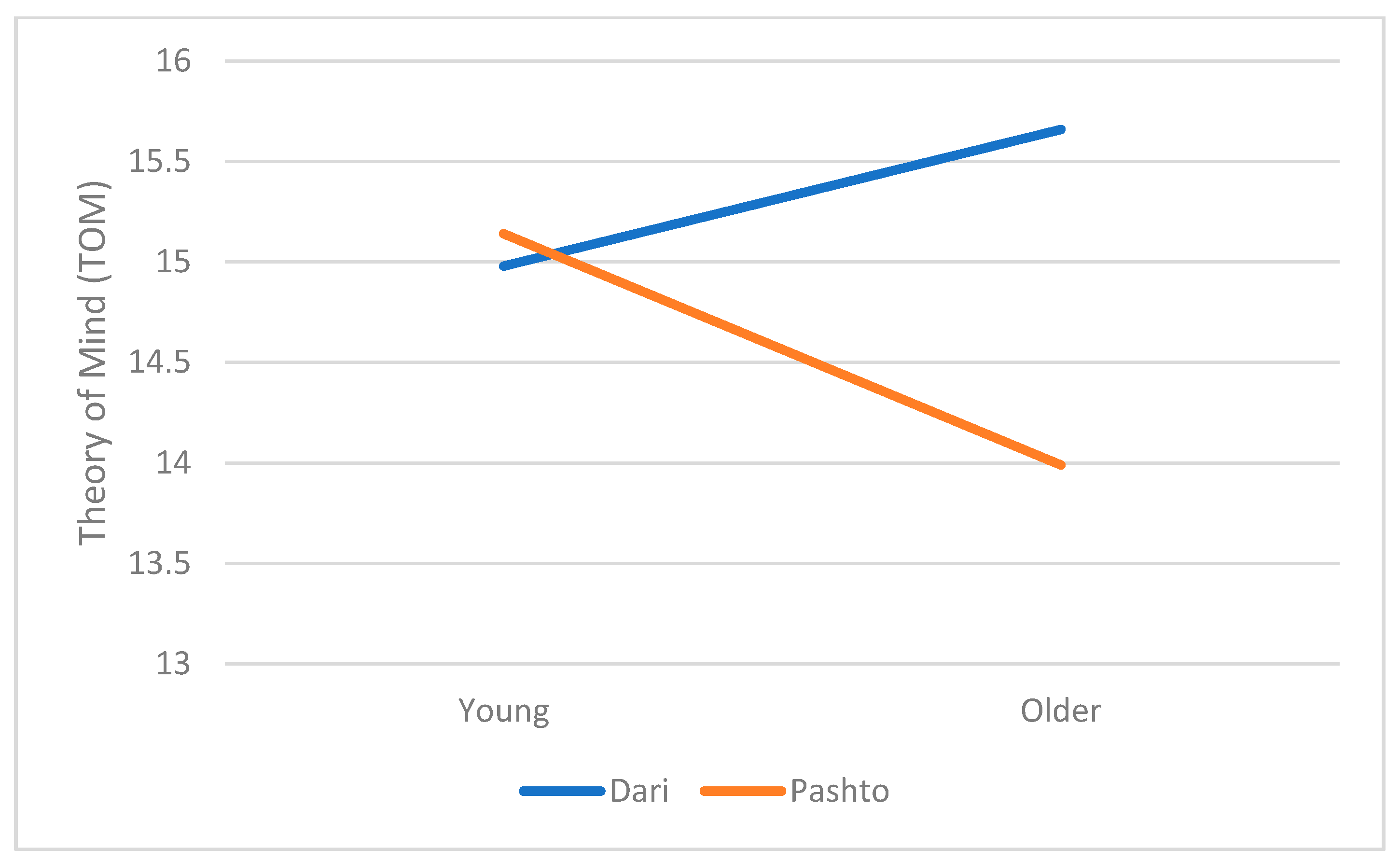

| Theory of mind | F (1, 604) = 6.53 p < 0.05 | F (1, 604) = 0.66 Ns | F (1, 604) = 9.65 p < 0.01 |

| Openness | F (1, 604) = 44.86 p < 0.001 | F (1, 604) = 3.02 Ns | F (1, 604) = 1.54 Ns |

| Gender role equality | F (1, 604) = 30.34 p < 0.001 | F (1, 604) = 6.23 p < 0.05 | F (1, 604) = 1.67 Ns |

| Suggestibility | F (1, 604) = 34.48 p < 0.001 | F (1, 604) = 8.04 p < 0.01 | F (1, 604) = 1.32 Ns |

| Authoritarianism | F (1, 604) = 1.74 Ns | F (1, 604) = 2.71 Ns | F (1, 604) = 2.26 Ns |

| Democratic values | F (1, 604) = 82.86 p < 0.001 | F (1, 604) = 1.78 Ns | F (1, 604) = 1.94 Ns |

| Βeta | R2 change | |

|---|---|---|

| Step1: Demographic | 0.13 ** | |

| Generation | 0.01 | |

| Gender | 0.02 | |

| Education | 0.03 | |

| Culture | 0.34 ** | |

| Step 2: Psycho-social | 0.20 ** | |

| Empathy | 0.07 | |

| ToM | 0.04 | |

| Openness | 0.13 * | |

| Gender role equality | 0.15 ** | |

| Suggestibility | −0.10 * | |

| Authoritarianism | 0.02 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Empathy | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Theory of mind | 0.17 ** 0.32 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Openness | 0.12 * −0.09 | 0.02 −0.04 | 1 | ||||

| 4. Gender role equality | 0.17 * 0.17 * | 0.16 ** 0.19 ** | 0.20 ** 0.06 | 1 | |||

| 5. Suggestibility | 0.07 −0.05 | −0.04 −0.05 | −0.12 * −0.19 ** | 0.02 −0.25 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Authoritarianism | −0.18 ** −0.30 ** | −0.12 * −0.23 ** | −0.11 * −0.12 ** | −0.05 0.05 | 0.12 * 0.06 | 1 | |

| 7. Democratic values | 0.02 0.18 ** | 0.02 0.16 ** | 0.24 ** 0.10 | 0.23 *** 0.10 | −0.15 ** −0.05 | −0.03 −0.08 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaviani, H.; Ahmadi, S.-J. A Cross-Cultural and Trans-Generational Study: Links between Psychological Characteristics and Socio-Political Tendency amongst Urban Population in Afghanistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126372

Kaviani H, Ahmadi S-J. A Cross-Cultural and Trans-Generational Study: Links between Psychological Characteristics and Socio-Political Tendency amongst Urban Population in Afghanistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126372

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaviani, Hossein, and Sayed-Jafar Ahmadi. 2021. "A Cross-Cultural and Trans-Generational Study: Links between Psychological Characteristics and Socio-Political Tendency amongst Urban Population in Afghanistan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 12: 6372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126372

APA StyleKaviani, H., & Ahmadi, S.-J. (2021). A Cross-Cultural and Trans-Generational Study: Links between Psychological Characteristics and Socio-Political Tendency amongst Urban Population in Afghanistan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126372