Abstract

This research proposes an updated version of homestay indicators for 10 existing component-level homestay requirements. The updated indicators were aimed to replace the decade-old original indicators for Thai homestay businesses. Besides, the 31 original homestay indictors were not statistically validated. In this study, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the statistical relevancy between the updated homestay indicators and the components. The SEM analysis involved two steps: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The EFA statistically regrouped the 31 updated indictors by six new homestay components. The six components and 31 updated indicators were further validated by CFA to determine the factor loadings and statistical reliability of the components and indicators. The factor loadings indicate the levels of importance that homestay guests attach to different homestay components and indicators. Therefore, Thai homestay operators should give priority to the components and indicators with high factor loadings.

1. Introduction

Tourism and hospitality are a major contributor to Thailand’s economy, with tourism revenue accounting for 17.7% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) (Ministry of Tourism and Sports, 2019). Thailand is renowned for unique cultures, traditional cuisine, and beautiful nature []. Homestay is a form of hospitality and lodging where guests or visitors are afforded with opportunities to observe and experience local culture and ways of life, in addition to accommodation and basic amenities [].

Homestay tourism offers visitors the opportunity to learn and experience local ways of life and cultures (Oranratmanee []. To be attractive and sustainable, homestay operation should be of small scale, flexible, and run by local community members. The determinants of the success and sustainability of homestay businesses include, e.g., homestay host family, authenticity, safety, location, accommodation, and activities [].

According to Kontogeorgopoulos, Churyen [], homestay is a means to monetize unused space in places of residence for economic return. In addition, homestay is a form of accommodation that combines the experiences of a family member’s home and conventional lodging facilities. A study by Takran, Chartrungruang [] found that a majority of native homestay operators failed to meet the minimum requirements or standards of homestay business due to limited access to relevant information sources.

Homestay tourism contributes to local economic betterment and strengthens social capital of the local community []. From the perspective of homestay guests, homestay tourism provides them with opportunities to learn and experience firsthand local cultures, customs, and livelihoods. According to Jiang [], local cultures and ways of life play an essential role in homestay tourism development.

Cultural resources are part of the cultural heritage of destinations and are largely related to customary practices, livelihoods, and local identity []. Meanwhile, tourism is largely viewed as a leisure-related activity separate from local culture and traditional ways of life [,]. However, recent decades have witnessed the convergence of culture and tourism (i.e., culture-oriented homestay tourism) as cultural heritage has been increasingly used as unique selling propositions to attract travelers to the tourist destinations [].

Homestay tourism is a source of income for local community members, especially in destinations with unique attractions or cultures []. Homestay tourism increasingly emphasizes the preservation of local ecosystems and ways of life of community members []. Besides, homestay tourism satisfies the unique needs of travelers who prioritize quality over quantity. Travelers increasingly attach more importance to local culture and ecosystem []. Active participation of local community members in homestay tourism operation and management contributes to inclusive local economic development [].

However, if improperly regulated, homestay tourism could have negative impacts on local communities and the environment [,]. As a result, the Ministry of Tourism and Sports of Thailand in 2011 introduced the homestay requirements or standards for Thai homestay businesses. The homestay requirements are instrumental for preservation of local ways of life and the environment []. The standards also provide homestay operators with guidelines to streamline the operation and administration of homestays [,].

The success and sustainability of homestay businesses are largely determined by the extent to which the homestay operators meet the basic requirements or standards, such as authenticity, safety, location, activities. As a result, the standards for homestay businesses would serve as a guideline for homestay operators with regard to basic requirements and expectations of homestay guests. The standards also promote collaboration between diverse groups of stakeholders [,].

The homestay standard of the Ministry of Tourism and Sports consists of 10 components and 31 indicators. However, the existing indicators were not statistically validated to determine their relevancy to the components. As a result, this research proposes updated homestay indicators, and statistical validation was carried out by using exploratory factor analysis. The homestay components and indicators were further validated by confirmatory factor analysis to determine the factor loadings and statistical reliability. In this research, factor loadings indicate the levels of importance that homestay guests attach to different homestay components and indicators.

2. Research Methodology

Table 1 tabulates the component- and indicator-level standards or requirements for homestay businesses in Thailand by the Ministry of Tourism and Sports. There are 10 component-level requirements and 31 related indicator-level requirements (i.e., original indicators). The 10 components include accommodation and amenities; food and beverage; safety to life and belongings; hospitality of host and family members; travel information and tour guide; natural resources and the environment; cultural heritage and livelihood; addition of value to local merchandise; homestay operation and management; marketing communication and promotion.

Table 1.

Component- and indicator-level requirements for Thai homestay businesses by the Ministry of Tourism and Sports of Thailand.

The original homestay indicators have been in use for nearly a decade (since 2011). Given rapid technological advancements and changes in travelers’ preferences over the past decade, modifications are necessary to remain relevant. Moreover, no statistical validation was carried out on the 31 original indicators to determine their relevancy to the 10 components.

As a result, this research proposes an updated version of homestay indicators (31 updated indicators) for 10 component-level requirements (Table 1). In the study, the updated indicators were transformed into a 31-question questionnaire (Appendix A) and validated with 337 Thai and international guests of homestays across Thailand. The questionnaire respondents were guests of a random sample of 12 homestays, all of which met the ministry’s homestay standards. According to Dawson, Peppe [], a proper sample size should be at least 10 times the total number of questions. Given that the number of questions was 31, the sample size was thus 337 homestay guests. The data collection was conducted by homestay operators between March and May 2018, which coincided with Songkran water festival in Thailand. Songkran marks the beginning of the traditional Thai New Year and the celebration covers a period of three days: 13–15 April.

In data collection, respondents were asked by homestay operators for their views on the importance of different updated indicators for the success of homestays, based on a 5-point Likert scale where 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, denote unimportant, of little importance, moderately important, important, and very important. According to Bayraktar, Tatoglu []; Na-nan, Chaiprasit []; Ismail Salaheldin []; Thanvisitthpon, Shrestha [], a measure scale could be used with self-assessment questions.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the statistical relevancy between the updated homestay indicators and the 10 component-level requirements. The SEM analysis involved two steps: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In this study, the EFA statistically regrouped the 31 updated indictors by six new homestay components rather than by the original 10 components (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the updated indicators and component-based factor weight scores.

Table 3.

Descriptions of the EFA-validated components and indicators.

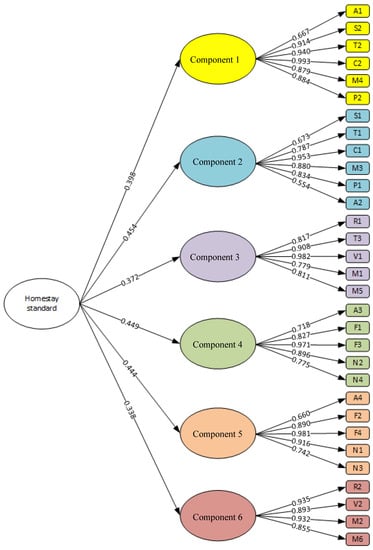

The six new components and 31 updated indicators were further validated by CFA to determine the factor loadings and reliability of the components and indicators (Table 4). Factor loadings indicate the levels of importance that homestay guests attach to different homestay components and indicators. A high factor loading suggests that the component or indicator plays an important role in the success and sustainability of homestays.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of EFA-validated components and indicators.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 2 tabulates the EFA results and component-based factor weight scores of the 31 updated homestay indicators. The updated indicators were regrouped by six EFA-validated homestay components. The 1st component consisted of six updated indictors: A1, S2, T2, C2, M4, and P2 with the factor weight scores of 0.762-0.976. The 2nd component consisted of six indictors: A2, S1, T1, C1, M3, and P1 (0.666–0.933), and the 3rd component comprised five indicators: R1, T3, V1, M1, and M5 (0.858–0.949). The 4th, 5th, and 6th components consisted of A3, F1, F3, N2, N4 (0.749–0.919); A4, F2, F4, N1, N3 (0.691–0.927); and R2, V2, M2, M6 (0.876–0.941), respectively. The descriptions of the updated indicators are provided in Table 1.

The factor weight scores of the 31 updated homestay indicators were greater than 0.3, given that a factor weight score >0.3 is statistically valid [,,,]. The eigenvalues of the revised six components were 6.186, 4.610, 3.997, 3.645, 3.251, and 2.666, respectively, given that an eigenvalue > 1.0 is acceptable, with the corresponding percentage of variance of 19.955, 14.872, 12.894, 11.758, 10.487, and 8.599. Table 3 presents the six EFA-validated homestay components and indicators.

In Figure 1, the factor loadings of six validated homestay components and 31 updated indicators were 0.338–0.454 and 0.554–0.993, respectively. According to Kim and Mueller [], a factor loading greater than 0.3 is statistically significant.

Figure 1.

The factor loadings of six validated homestay components and related indicators.

In addition, the chi-square = 10901.185, degree of freedom (df) = 465, p = 0.000, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.900, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.047, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) = 0.963, NFI Deltal1 = 0.943, confirmatory fit index (CFI) = 0.975, incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.975, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.967, and root mean square residue (RMR) = 0.034. According to Baumgartner and Homburg [], Gatignon [] and Hooper, Coughlan [], GFI, AGFI, NFI Deltal1, CFI, IFI, and TLI should be close to 1, while RMSEA and RMR should not exceed 0.05.

Table 4 presents the CFA results of the six validated components and 31 updated homestay indicators. The reliability (R2) of the indicators under the 1st component were 0.444–0.986, and those under the 2nd component were 0.307–0.907. The R2 of the indicators under 3rd and 4th components were 0.608–0.965 and 0.515–0.943. The R2 of the indictors under 5th and 6th components were 0.435–0.961 and 0.731–0.873, given that R2 > 0.3 is statistically acceptable. The full descriptions of the updated indicators were provided in Table 3.

The composite reliability (CR) of component 6 (stakeholder involvement strategy) was the largest (0.955), followed by component 1 (congruence with local ways of life and inclusive local economic development; 0.953), component 3 (roles of local stakeholders in homestay tourism longevity; 0.948), component 4 (cleanliness, infrastructure, and the environment; 0.940), component 5 (identity and carrying capacity of homestay; 0.931), and component 2 (homestay operation and hospitality management; 0.926). The corresponding average variance extracted (AVE) was 0.678–0.841. According to Fornell and Larcker [], the CFA construct component is statistically valid if CR > 0.6 or AVE > 0.5.

A high factor loading indicates the indicator that homestay guests attach considerable importance and thereby plays a crucial role in the success and sustainability of local homestay businesses. In Figure 1, the indicator C2 (action plans to preserve traditional livelihoods and local ways of life) under component 1 had the highest factor loading (0.993). Specifically, local ways of life and cultures of tourist destinations have been increasingly adopted as a differentiation strategy by many homestay businesses [,,]. Culture-oriented homestay tourism helps promote local culture and traditions and is a potential source of income of local community, which in turn supports and strengthens cultural production and creativity [,,].

The indicator V1 (availability of a wide selection of local merchandise for sale to visitors, and the offerings should be diverse to minimize price competition) under component 3 had the second highest factor loading (0.982). Culture-oriented homestay tourism promotes local traditions and also serves as a marketing tool to sell locally made crafts and services to visitors [,]. As a result, an increasing number of local tourist destinations integrate local cultures into their offerings and services to appeal to visitors’ unique needs [,].

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

This research proposed an updated version of homestay indicators associated with 10 component-level homestay requirements to replace the 31 original indicators for homestay businesses in Thailand. The original indictors have been in use for nearly a decade, and no statistical validation was carried out to determine the relevancy to the 10 components. The existing 10 components were accommodation and amenities; food and beverage; safety to life and belongings; hospitality of host and family members; travel information and tour guide; natural resources and the environment; cultural heritage and livelihood; addition of value to local merchandise; homestay operation and management; marketing communication and promotion.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to determine the statistical relevancy between the updated homestay indicators and the components. The SEM analysis involved two steps: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). In this research, the EFA statistically regrouped the 31 updated indictors by six new homestay components instead of by the original 10 components. The six new homestay components were congruence with local ways of life and inclusive local economic development; homestay operation and hospitality management; roles of local stakeholders in homestay tourism longevity; cleanliness, infrastructure, and the environment; local identity and carrying capacity of homestay; stakeholder involvement strategy.

The six components and 31 updated indicators were further validated by CFA to determine the factor loadings and reliability of the components and indicators. A high factor loading suggests that the particular indicator plays an important role in the success and sustainability of homestay tourism and local community. The CFA results revealed that the indicators C2 (action plans to preserve traditional livelihoods and local ways of life) and V1 (availability of a wide selection of local merchandise for sale to visitors, and the offerings should be diverse to minimize price competition) had the highest (0.993) and second-highest factor loadings (0.982).

The findings indicated that homestay guests attached considerable importance to both homestay indicators. As a result, Thai homestay operators should take into consideration local cultures and ways of life in the formulation and implementation of their business plans. Furthermore, the research findings are consistent with [,,], who found that homestay businesses increasingly adopt the local ways of life and cultures as the differentiation strategy to attract visitors. The findings are also consistent with [,,], who reported that culture-oriented homestay tourism helps promote local culture and traditions and is a potential source of income of local community.

The research findings are expected to contribute to improvement in homestay operation in Thailand as the owners could refer to the resulting factor loadings to identify the requirements or standards that are currently inadequate or lacking in their homestay operation. The shortcomings could then be addressed by immediate and long-term action plans, with priority given to the homestay indicators with high factor loadings. Moreover, the statistically validated homestay indicators could be further developed into a standardized checklist to evaluate and grade homestay businesses in terms of the extent to which they satisfy the homestay standards.

In this current research, the homestay indicators were validated by using a sample of 337 homestay visitors who stayed in a homestay in the central region of Thailand. To address the issue of limited geography, future research will cover several geographical regions and longer periods of data collection (from three months to one year). In addition, future participating homestay operators will be offered a brief training session to avoid incomplete and incorrect data collection.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Thai Homestay Business Indicator Satisfactions

Appendix A.1. Demographics and Generic Information

1.1. Gender

▯ Male

▯ Female

1.2. Age (years)

1.3. Education level

▯ Below primary

▯ Primary school

▯ Lower Secondary

▯ Upper secondary

▯ University

1.4. Occupation

▯ Private company employee

▯ Self-employed

▯ Student

▯ Government

▯ Business owner

▯ Other

Appendix A.2. Thai Homestay Business Indicator Satisfactions

The Thai hmestay business indicator satisfactions have an 5-point Likert scale, 1 represents not related, 5 strongly disagree, and 10 strongly agree.

| Indicator ID | Description | 1 Strongly Disagree and 5 Strongly Agree | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| A1 | In addition to functionality and provision of basic amenities, guests’ privacy should be taken into consideration in the accommodation layout. | |||||

| A2 | Cleanliness, accessibility, and guest-centered hospitality | |||||

| A3 | Proper sanitation procedure and ecologically friendly sewage management | |||||

| A4 | Common area on the premises where homestay guests could observe or partake in traditional ways of life of the local community, in addition to relaxation. | |||||

| F1 | Types of dishes and cooking ingredients | |||||

| F2 | Provision of clean drinking water and appliances for modern living | |||||

| F3 | Environmentally friendly and clean food containers and tableware | |||||

| F4 | Provision of traditional cooking utensils and local condiments (with instruction), in addition to clean food preparation area and modern kitchen utensils | |||||

| S1 | Availability of first aid kit | |||||

| S2 | Provision of security for guests and their belongings | |||||

| R1 | Warm and cordial reception by homestay host and family members as well as by local community members for the long-term sustainability of homestay business | |||||

| R2 | Multisector collaboration (i.e., homestay host, other local businesses and community members) to create activities that promote local culture and traditional ways of life | |||||

| T1 | Travel information and local destination highlights with community consensus and seasonal updates | |||||

| T2 | Local community oriented travel activity that respects traditional ways of life | |||||

| T3 | Provision of tour guides with knowledge of local community. The aim is to create economic opportunities for community members, including developing new skills, finding jobs, and starting new businesses. | |||||

| N1 | Availability of local attractions and/or nearby tourist destinations that embody local culture and traditional ways of life | |||||

| N2 | Proper supervision and maintenance of tourist destinations with emphasis on environmental conservation and long-term sustainability | |||||

| N3 | Strategic and action plans to mitigate the impacts of homestay tourism on the environment and ways of life and identity of the local community | |||||

| N4 | Action plans to lessen the impacts of homestay tourism on local natural resources and environment with the goal to reduce global warming | |||||

| C1 | Incorporating local culture and traditions into homestay offerings and hospitality services | |||||

| C2 | Action plans to preserve traditional livelihoods and local ways of life | |||||

| V1 | Availability of a wide selection of local merchandise for sale to visitors, and the offerings should be diverse to minimize price competition. | |||||

| V2 | Procedure that engages local government and community members in value creation and addition to local merchandise | |||||

| M1 | Forming an alliance of homestay operators with organizational structure and specific duties for representative members | |||||

| M2 | Establishment of board of directors (BOD) for the alliance, and the board should consist of representatives from the local community. | |||||

| M3 | Duties and responsibilities of BOD | |||||

| M4 | Inclusive distribution of economic gain from homestay tourism in proportion to effort and contributions | |||||

| M5 | Creating an online hub where visitors are able to make reservations for a variety of services offered by local community businesses (e.g., local transport, tour guide, tourist attractions), in addition to accommodation reservation. | |||||

| M6 | Itemized price list of offerings and services to minimize dispute and build trust | |||||

| P1 | Adoption of offline and online media platforms for marketing communication to promote homestay tourism and tourist destinations in the local community | |||||

| P2 | Marketing communication strategy that emphasizes inclusivity (i.e., all stakeholders contribute to the strategy formulation) and evaluation of the strategy effectiveness | |||||

Any suggestion.

References

- Thanvisitthpon, N. A social impact assessment of the tourism development policy on a heritage city, Ayutthaya Historical Park, Thailand. Asian Tour. Manag. 2015, 6, 103–144. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, D.; Kinginger, C. Exploring the potential of high school homestays as a context for local engagement and negotiation of difference. In Social and Cultural Aspects of Language Learning in Study Abroad; John Benjamins Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 37, pp. 15–177. [Google Scholar]

- Oranratmanee, R. Re-utilizing space: Accommodating tourists in homestay houses in northern Thailand. J. Archit. Plan. Res. Stud. (Jars) 2012, 8, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- The ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Homestay Standard; The ASEAN Secretariat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N.; Churyen, A.; Duangsaeng, V. Homestay tourism and the commercialization of the rural home in Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takran, T.; Chartrungruang, B.; Tantranont, N.; Somhom, S. Constructing a Thai Homestay Standard Assessment Model by Implementing a Decision Tree Technique. Int. J. Comput. Internet Manag. 2017, 25, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, R.; Mura, P.; Rajaratnam, S.D. Social capital in Malaysian homestays: Exploring hosts’ social relations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1028–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Study on the Inheritance and Development of Local Culture in the Homestay. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Economics and Management, Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Suzhou, China, 18–19 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thanvisitthpon, N. Urban environmental assessment and social impact assessment of tourism development policy: Thailand’s Ayutthaya Historical Park. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayat, K. The nature of cultural contribution of a community-based homestay programme. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2009, 5, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Vinh, N.Q. Destination culture and its influence on tourist motivation and tourist satisfaction of homestay visit. J. Fac. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2013, 3, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Promnil, N. Market Segmentation in Community-Based Homestay Tourism in Thailand. J. Talent Dev. Excell. 2020, 12, 2205–2216. [Google Scholar]

- Saraithong, W.; Chancharoenchai, K. Tourists behaviour in Thai homestay business. Int. J. Manag. Cases 2011, 13, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P. Local knowledge and adult learning in environmental adult education: Community-based ecotourism in southern Thailand. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2009, 28, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Razzaq, A.R.A. Homestay program and rural community development in Malaysia. J. Ritsumeikan Soc. Sci. Hum. 2010, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M.; Wong, P.P. Residents’ perception of tourism impacts: A case study of homestay operators in Dachangshan Dao, North-East China. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, B. Impact of Homestay Tourism on Livelihood: A Case Study of Ghale Guan, Lamjung, Nepal. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Ås, Norway, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, R.B.; Faisal, F. Homestay Development with Asean Homestay Standard Approach in Nglanggeran Tourism Village, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference One Belt, One Road, One Tourism, Palembang, Indonesia, 22–24 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sawatsuk, B.; Darmawijaya, I.G.; Ratchusanti, S.; Phaokrueng, A. Factors determining the sustainable success of community-based tourism: Evidence of good corporate governance of Mae Kam Pong Homestay, Thailand. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Aff. 2018, 3, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Hung, K.; Li, M. Development of measurement scale for functional congruity in guest houses. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K. An Assessment and Development of Service Quality Framework of Homestay in Sikkim. Ph.D. Thesis, Shri Ramasamy Memorial University Sikkim, Gangtok, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nor, N.A.M.; Kayat, K. The Challenges of Community-Based Homestay Programme in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Regional Conference on Tourism Research, Penang, Malaysia, 13–14 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, R.J.; Peppe, R.; Wang, M. An agent-based model for risk-based flood incident management. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, E.; Tatoglu, E.; Zaim, S. An instrument for measuring the critical factors of TQM in Turkish higher education. Total Qual. Manag. 2008, 19, 551–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na-nan, K.; Chaiprasit, K.; Pukkeeree, P. A validation of the performance management scale. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2018, 35, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Salaheldin, S. Critical success factors for TQM implementation and their impact on performance of SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2009, 58, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanvisitthpon, N.; Shrestha, S.; Pal, I.; Ninsawat, S.; Chaowiwat, W. Assessment of flood adaptive capacity of urban areas in Thailand. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongma, W.; Leelapattana, W.; Hung, J.-T. Tourists’ satisfaction towards tourism activities management of Maesa community, Pongyang sub-district, Maerim district, Chiang Mai province, Thailand. Asian Tour. Manag. 2011, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sekorarith, N. Key Factors Influencing Thai Travelers to Choose a Homestay Accommodation in Thailand. Master’s Thesis, Thammasat University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, S.A.; Othman, N.A.; Muhammad, N.M.N. Tourist perceived value in a community-based homestay visit: An investigation into the functional and experiential aspect of value. J. Vacat. Mark. 2011, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Laymoun, M.; Alsardia, K.; Albattat, A. Service quality and tourist satisfaction at homestays. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjuraman, V.; Hussin, R. Challenges of community-based homestay programme in Sabah, Malaysia: Hopeful or hopeless? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. Tourism in rural areas: Kedah, Malaysia. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwoga, N.B.; Maturo, E. Motivation-based segmentation of rural tourism market in African villages. Dev. South. Afr. 2020, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinginger, C.; Carnine, J. Language learning at the dinner table: Two case studies of French homestays. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2019, 52, 850–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, M.; Guo, Z.; Sun, P.; Geng, F.; Voon, B. China Tourists’ Experiences with Longhouse Homestays in Sarawak. Int. J. Serv. Manag. Sustain. 2019, 4, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, L. A review of entrepreneurship research published in the hospitality and tourism management journals. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, S.A.; Othman, N.A.; Muhammad, N.M.N. The moderating influence of psychographics in homestay tourism in Malaysia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.Z.; Jabeen, F.; Khan, M. Entrepreneurs choice in business venture: Motivations for choosing home-stay accommodation businesses in Peninsular Malaysia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Som, A.P.M.; Henderson, J.C. Tourism crises and island destinations: Experiences in Penang, Malaysia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razzaq, A.R.A.; Hadi, M.Y.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Hamzah, A.; Khalifah, Z.; Mohamad, N.H. Local community participation in homestay program development in Malaysia. J. Mod. Account. Audit. 2011, 7, 1418. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.D. The Role of Local Communities in Community-Based Tourism Development in Traditional Tea Production Areas in Thai Nguyen Province, Vietnam. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.; Wall, G. Evaluating ecotourism: The case of North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin, M.; Othman, N.; Awang, A.R. Community based homestay programme: A personal experience. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 42, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-T.; Lin, T.-P.; Hwang, R.-L.; Huang, Y.-J. Carbon dioxide emissions generated by energy consumption of hotels and homestay facilities in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Simmons, D.G.; Frampton, C. Energy use associated with different travel choices. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Dahalan, N.; Jaafar, M. Tourists’ perceived value and satisfaction in a community-based homestay in the Lenggong Valley World Heritage Site. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, V.; Walter, P. Community-based ecotourism and the transformative learning of homestay hosts in Cambodia. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.P.; Halpenny, E.A. Homestays as an alternative tourism product for sustainable community development: A case study of women-managed tourism product in rural Nepal. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2013, 10, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusiran, A.K.; Xiao, H. Challenges and community development: A case study of homestay in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, P.; Coghlan, A.; Bhattacharya, P. Homestays’ contribution to community-based ecotourism in the Himalayan region of India. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2016, 41, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choibamroong, T.; Laws, E.; Richins, H.; Agrusa, J.; Scott, N. A stakeholder approach for sustainable community-based rural tourism development in Thailand. In Tourist Destination Governance: Practice, Theory and Issues; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.C.; Wall, G. Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, J.; Lynch, P.; Anastasiadou, C. Community non-participation in homestays in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh, India. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoasong, M.Z.; Kimbu, A.N. Informal microfinance institutions and development-led tourism entrepreneurship. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, R.; Kunjuraman, V. Sustainable community based tourism (CBT) through homestay programme in Sabah, East Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Social Sciences Research ICSSR, Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 9–10 June 2014; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos, F.; Niakas, D.; Tountas, Y. Comparison between exploratory factor-analytic and SEM-based approaches to constructing SF-36 summary scores. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H.W.; Morin, A.J.; Parker, P.D.; Kaur, G. Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, D.D. Exploratory or Confirmatory Factor Analysis? SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied psychometrics: Sample size and sample power considerations in factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in general. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.-L.; Lin, Y.-M. Factors underlying college students’ choice homestay accommodation while travelling. World Trans. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2011, 9, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hui-min, G.; Jinging, G.; Fan, G.; Shan, L. Study on green tourism consumptions of Chinese tourist with different environment perception. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Beijing, China, 8–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- QU, Q. Research on Symbiotic Community Space Participated by Citizen and Villager in Village. Master’s Thesis, Poltecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Karki, K.; Chhetri, B.B.K.; Chaudhary, B.; Khanal, G. Assessment of socio-economic and environmental outcomes of the homestay program at Amaltari village of Nawalparasi, Nepal. J. Nat. Resour. Manag. 2019, 1, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, D.K.; Diwyarthi, N.D.M.S. Tourist Satisfaction towards Management of Home Stay in Lumajang District. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference One Belt, One Road, One Tourism, Palembang, Indonesia, 22–24 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- KC, B. Ecotourism for wildlife conservation and sustainable livelihood via community-based homestay: A formula to success or a quagmire? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Lin, C.; Lin, C.-W.R.; Wu, K.-J.; Sriphon, T. Ecotourism development in Thailand: Community participation leads to the value of attractions using linguistic preferences. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, B.; Anup, K.; Sapkota, R.P. Environmental Impacts of Community-Based Home stay Ecotourism in Nepal. Gaze J. Tour. Hosp. 2020, 11, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escolar-Jimenez, C.C. Cultural homestay enterprises: Sustainability factors in Kiangan, Ifugao. Hosp. Soc. 2020, 10, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E. Exploring the relevance of sustainability to micro tourism and hospitality accommodation enterprises (MTHAEs): Evidence from home-stay owners. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommaret, F. Conservation of cultural landscapes in Bhutan. In Cultural Landscapes of South Asia; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sarobol, A. Costume development model for tourism promotion in Mae Hong Son province, Thailand. In SHS Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.; Ibrahim, Y. Model of sustainable community participation in homestay program. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-O.; Mueller, C.W. Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issues; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1978; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H. Statistical Analysis of Management Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, L. Research on the Development Path of Yangjiale Homestay in the Background of Rural Revitalization Strategy. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Advances in Social Sciences, London, UK, 28–30 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).