Wheat Bread Fortification by Grape Pomace Powder: Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ingredients and Breadmaking

2.2. Dough Characterization

2.3. Bread Quality Characteristics

2.3.1. Water Activity, Moisture Content, Volume, Specific Volume, and Baking-Loss

2.3.2. Texture Attributes of Bread Crumb

2.3.3. Proximate Composition of Breads

2.3.4. Color Analysis

2.3.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC), FRAP, and ABTS Assays

2.4. Sensory Evaluation of Breads

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Grape Pomace inclusion on Dough Rheological Properties

3.2. Physiochemical Characterization of Grape Pomace Powder and Breads

3.3. Chemical Composition of Breads

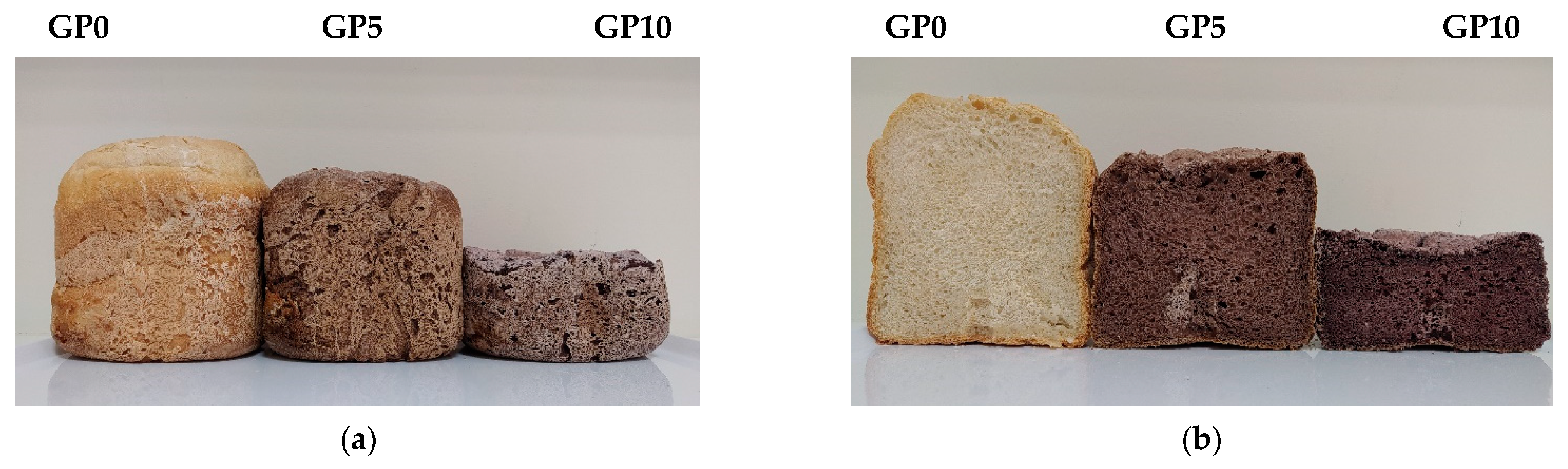

3.4. Color Analysis

3.5. Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activity

3.6. Sensory Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ameh, M.O.; Gernah, D.I.; Igbabul, B.D. Physico-Chemical and Sensory Evaluation of Wheat Bread Supplemented with Stabilized Undefatted Rice Bran. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. UN Doc. A/RES/70/1. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Tolve, R.; Pasini, G.; Vignale, F.; Favati, F.; Simonato, B. Effect of Grape Pomace Addition on the Technological, Sensory, and Nutritional Properties of Durum Wheat Pasta. Foods 2020, 9, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Padalino, L.; D’Antuono, I.; Durante, M.; Conte, A.; Cardinali, A.; Linsalata, V.; Mita, G.; Logrieco, A.F.; Del Nobile, M.A. Use of olive oil industrial by-product for pasta enrichment. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simonato, B.; Trevisan, S.; Tolve, R.; Favati, F.; Pasini, G. Pasta fortification with olive pomace: Effects on the technological characteristics and nutritional properties. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Montealegre, R.; Romero Peces, R.; Chacón Vozmediano, J.L.; Martínez Gascueña, J.; García Romero, E. Phenolic compounds in skins and seeds of ten grape Vitis vinifera varieties grown in a warm climate. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Ou, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Szkudelski, T.; Delmas, D.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Dietary polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: Human Study and Clinical Trial. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3371–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.A.; Knaze, V.; Zamora-Ros, R. Polyphenols: Dietary assessment and role in the prevention of cancers. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Cao, X.; Wang, J. Preparation and modification of high dietary fiber flour: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobera, A.; Cañellas, J. Dietary fibre content and antioxidant activity of Manto Negro red grape (Vitis vinifera): Pomace and stem. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Penner, M.H.; Zhao, Y. Chemical composition of dietary fiber and polyphenols of five different varieties of wine grape pomace skins. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2712–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, A.; Zhao, Y. Wine grape pomace as antioxidant dietary fibre for enhancing nutritional value and improving storability of yogurt and salad dressing. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jane, M.; McKay, J.; Pal, S. Effects of daily consumption of psyllium, oat bran and polyGlycopleX on obesity-related disease risk factors: A critical review. Nutrition 2019, 57, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Dziki, D.; Świeca, M.; Sȩczyk, Ł.; Rózyło, R.; Szymanowska, U. Bread enriched with Chenopodium quinoa leaves powder—The procedures for assessing the fortification efficiency. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 1226–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa, I.F.; Aruna, T.E.; Raji, A.O. Nutritive value and acceptability of bread fortified with moringa seed powder. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, G.A.; Rocha, M.; Salas-Mellado, M.M. Improvement of protein content and effect on technological properties of wheat. Food Res. 2018, 2, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshmi, S.K.; Sudha, M.L.; Shashirekha, M.N. Starch digestibility and predicted glycemic index in the bread fortified with pomelo (Citrus maxima) fruit segments. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantuono, A.; Ferracane, R.; Vitaglione, P. Potential bioaccessibility and functionality of polyphenols and cynaropicrin from breads enriched with artichoke stem. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainente, F.; Menin, A.; Alberton, A.; Zoccatelli, G.; Rizzi, C. Evaluation of the sensory and physical properties of meat and fish derivatives containing grape pomace powders. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoozani, A.A.; Kebede, B.; Birch, J.; El-Din Ahmed Bekhit, A. The effect of bread fortification with whole green banana flour on its physicochemical, nutritional and in vitro digestibility. Foods 2020, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Gammal, R.; Ghoneim, G.; ElShehawy, S. Effect of Moringa Leaves Powder (Moringa oleifera) on Some Chemical and Physical Properties of Pan Bread. J. Food Dairy Sci. 2016, 7, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguchi, M.; Morimoto, N.; Abe, M.; Yoshino, Y. Effect of maitake (Grifola frondosa) mushroom powder on bread properties. J. Food Sci. 2001, 66, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Ramos, K.C.; Sanz-Ponce, N.; Haros, C.M. Evaluation of technological and nutritional quality of bread enriched with amaranth flour. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 114, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayta, M.; Özuğur, G.; Etgü, H.; Şeker, İ.T. Effect of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) pomace on the quality, total phenolic content and anti-radical activity of bread. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Almusallam, A.S.; Al-Salman, F.; AbdulRahman, M.H.; Al-Salem, E. Rheological properties of water insoluble date fiber incorporated wheat flour dough. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros-Yupanqui, M.; Zagotto, A.; Alberton, A.; Lante, A.; Zagotto, G.; Ribaudo, G.; Rizzi, C. Monitoring the antioxidant activity of an eco-friendly processed grape pomace along the storage. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AACC. Approved Method of the AACC, 10th ed.; American Association of Cereal Chemists, Ed.; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Texture Technologies Corp. Texture Analysis Procedures. In AIB Standard Procedures; Texture Technologies Corp.: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemist, Ed.; The Association of Official Analytical Chemist: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino-García, R.; González-SanJosé, M.L.; Rivero-Pérez, M.D.; García-Lomillo, J.; Muñiz, P. The effects of heat treatment on the phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of red wine pomace seasonings. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simonato, B.; Tolve, R.; Rainero, G.; Rizzi, C.; Sega, D.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Giuberti, G. Technological, nutritional, and sensory properties of durum wheat fresh pasta fortified with Moringa oleifera L. leaf powder. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Mesure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballus, C.A.; Meinhart, A.D.; De Souza Campos, F.A.; Godoy, H.T. Total phenolics of virgin olive oils highly correlate with the hydrogen atom transfer mechanism of antioxidant capacity. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2015, 92, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Masa, A.; Tardaguila, J. Evaluation of the aroma descriptors variability in Spanish grape cultivars by a quantitative descriptive analysis. Euphytica 2009, 165, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Codină, G.G.; Popa, C. Effect of the addition of Psyllium fiber on wheat flour dough rheological properties. Recent Res. Med. Biol. Biosci. 2013, XII, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Anil, M. Using of hazelnut testa as a source of dietary fiber in breadmaking. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šporin, M.; Avbelj, M.; Kovač, B.; Možina, S.S. Quality characteristics of wheat flour dough and bread containing grape pomace flour. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 24, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girard, A.L.; Awika, J.M. Effects of edible plant polyphenols on gluten protein functionality and potential applications of polyphenol–gluten interactions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 2164–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, Z.; Shahedi, M.; Kadivar, M. Effects of pumpkin powder addition on the rheological, sensory, and quality attributes of Taftoon bread. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.; Oliete, B.; Caballero, P.A.; Ronda, F.; Blanco, C.A. Effect of nut paste enrichment on wheat dough rheology and bread volume. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2008, 14, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belghith Fendri, L.; Chaari, F.; Maaloul, M.; Kallel, F.; Abdelkafi, L.; Ellouz Chaabouni, S.; Ghribi-Aydi, D. Wheat bread enrichment by pea and broad bean pods fibers: Effect on dough rheology and bread quality. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F.; Simeone, R. Quality evaluation of re-milled durum wheat semolinas used for bread-making in Southern Italy. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004, 219, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualone, A.; Laddomada, B.; Spina, A.; Todaro, A.; Guzmàn, C.; Summo, C.; Mita, G.; Giannone, V. Almond by-products: Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and evaluation of their potential use in composite dough with wheat flour. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 89, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehfooz, T.; Mohsin Ali, T.; Arif, S.; Hasnain, A. Effect of barley husk addition on rheological, textural, thermal and sensory characteristics of traditional flat bread (chapatti). J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 79, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironeasa, S.; Zaharia, D.; Codină, G.G.; Ropciuc, S.; Iuga, M. Effects of Grape Peels Addition on Mixing, Pasting and Fermentation Characteristics of Dough from 480 Wheat Flour Type. Bull. UASVM Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 75, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammed, A.M.; Ozsisli, B.; Simsek, S. Utilization of Microvisco-Amylograph to Study Flour, Dough, and Bread Qualities of Hydrocolloid/Flour Blends. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Restuccia, C.; Palmeri, R.; Fallico, B.; Arena, E. Characterization of prickly pear peel flour as a bioactive and functional ingredient in bread preparation. Foods 2020, 9, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Q.; Ranawana, V.; Hayes, H.E.; Hayward, N.J.; Stead, D.; Raikos, V. Addition of broad bean hull to wheat flour for the development of high-fiber bread: Effects on physical and nutritional properties. Foods 2020, 9, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Reyes, I.; Carrera-Tarela, Y.; Vernon-Carter, E.J.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J. Charcoal bread: Physicochemical and textural properties, in vitro digestibility, and dough rheology. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2020, 21, 100227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakov, G.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Ivanova, N.; Stamatovska, V.; Dimov, I. Effect of grape pomace powder addition on chemical, nutritional and technological properties of cakes. LWT 2020, 134, 109950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, E.K.; Ryan, L.A.M.; Dal Bello, F. Impact of sourdough on the texture of bread. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, T.; Yu, W.; Yang, N.; Jin, Z.; Xu, X. Structural, thermal and rheological properties of gluten dough: Comparative changes by dextran, weak acidification and their combination. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narendranath, N.V.; Power, R. Relationship between pH and medium dissolved solids in terms of growth and metabolism of lactobacilli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during ethanol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2239–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, J.T.; Chang, Y.H.; Shiau, S.Y. Rheological, antioxidative and sensory properties of dough and Mantou (steamed bread) enriched with lemon fiber. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 61, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Świeca, M.; Dziki, D.; Anders, A.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. Antioxidant, nutritional and functional characteristics of wheat bread enriched with ground flaxseed hulls. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivam, A.S.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Quek, S.; Perera, C.O. Properties of bread dough with added fiber polysaccharides and phenolic antioxidants: A review. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, R163–R174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W. Bread fortified with anthocyanin-rich extract from black rice as nutraceutical sources: Its quality attributes and in vitro digestibility. Food Chem. 2016, 196, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, Y.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Deka, S.C. Bread fortified with dietary fibre extracted from culinary banana bract: Its quality attributes and in vitro starch digestibility. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschia, M.; Peressini, D.; Sensidoni, A.; Brennan, C.S. The effects of dietary fibre addition on the quality of common cereal products. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Lorusso, A.; Montemurro, M.; Gobbetti, M. Use of sourdough made with quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) flour and autochthonous selected lactic acid bacteria for enhancing the nutritional, textural and sensory features of white bread. Food Microbiol. 2016, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonato, B.; Pasini, G.; Giannattasio, M.; Peruffo, A.D.B.; De Lazzari, F.; Curioni, A. Food allergy to wheat products: The effect of bread baking and in vitro digestion on wheat allergenic proteins. A study with bread dough, crumb, and crust. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5668–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoye, C.; Ross, C.F. Total Phenolic Content, Consumer Acceptance, and Instrumental Analysis of Bread Made with Grape Seed Flour. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Tseng, A.; Cavender, G.; Ross, A.; Zhao, Y. Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Sensory Qualities of Wine Grape Pomace Fortified Baked Goods. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, S1811–S1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Water Absorption (%) | Stability (min) | Development Time (min) | Degree of Softening (UB) | Quality Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 55.50 ± 0.00 a | 5.80 ± 0.72 a | 1.40 ± 0.10 a | 76.33 ± 4.73 a,b | 41.67 ± 13.05 a |

| GP5 | 56.80 ± 0.17 b | 7.50 ± 0.00 b | 1.37 ± 0.12 a | 81.33 ± 6.03 a | 80.33 ± 3.06 b |

| GP10 | 60.03 ± 0.46 c | 8.27 ± 0.55 b | 1.40 ± 0.10 a | 67.00 ± 3.00 b | 87.33 ± 6.51 b |

| Sample | L (mm) | P (mm) | P/L | G (cm3) | W (10−4 J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 106.33 ± 11.72 a | 76.67 ± 4.51 a | 0.73 ± 0.12 a | 22.97 ± 1.29 a | 268.67 ± 8.62 a |

| GP5 | 30.00 ± 1.00 b | 165.33 ± 4.62 b | 5.52 ± 0.32 b | 12.20 ± 0.20 b | 222.67 ± 3.51 b |

| GP10 | 15.33 ± 1.15 c | 179.33 ± 9.02 b | 11.75 ± 1.12 c | 8.70 ± 0.35 c | 118.33 ± 11.72 c |

| Sample | Gelatinization Maximum (AU) | Start of Gelatinization (°C) | Gelatinization Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 1301.67 ± 17.56 a | 64.00 ± 0.87 a | 92.30 ± 0.75 a |

| GP5 | 1831.67 ± 42.52 b | 64.00 ± 0.87 a | 93.30 ± 0.52 a |

| GP10 | 1943.33 ± 11.55 c | 64.50 ± 1.50 a | 93.70 ± 0.75 a |

| Sample | Water Activity | Moisture content (%) | pH | Volume (cm3) | Specific Volume (cm3/g) | Firmness (N) | Baking-Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 0.96 ± 0.01 a | 43.47 ± 0.42 a | 5.73 ± 0.38 a | 2623 ± 52 a | 5.52 ± 0.11 a | 1.0 ± 0.10 a | 13.87 ± 0.00 a |

| GP5 | 0.97 ± 0.00 a | 41.46 ± 1.71 a | 4.44 ± 0.03 b | 1691 ± 104 b | 3.59 ± 0.27 b | 21.8 ± 1.44 b | 14.51 ± 1.92 a |

| GP10 | 0.97 ± 0.01 a | 40.58 ± 3.70 a | 3.98 ± 0.01 c | 1334 ± 63 c | 2.82 ± 0.13 c | 23.2 ± 1.65 c | 14.05 ± 0.77 a |

| Sample | Crude Lipid | Crude Protein | Total Starch | Total Dietary Fiber | Ash | Free Sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 0.12 ± 0.05 a | 12.4 ± 0.05 a | 85.5 ± 2.82 c | 2.8 ± 1.00 a | 1.0 ± 0.01 a | 1.6 ± 0.02 a |

| GP5 | 0.50 ± 0.22 b | 12.3 ± 0.13 a | 82.9 ± 0.89 b | 3.9 ± 0.74 b | 1.1 ± 0.01 a | 1.8 ± 0.03 a |

| GP10 | 0.87 ± 0.06 b | 12.1 ± 0.03 a | 75.3 ± 1.95 a | 6.3 ± 1.07 c | 1.4 ± 0.02 b | 1.9 ± 0.03 a |

| Sample | Crust | ∆E | Crumb | ∆E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |||

| GP0 | 59.92 ± 1.07 a | 6.90 ± 0.59 a | 27.71 ± 1.13 a | nd | 64.78 ± 1.03 a | 1.70 ± 0.28 a | 28.70 ± 1.41 a | nd |

| GP5 | 55.47 ± 0.39 b | 5.71 ± 0.47 b | 13.84 ± 0.28 b | 14.61 | 48.34 ± 0.58 b | 4.25 ± 0.56 b | 17.45 ± 0.91 b | 20.08 |

| GP10 | 52.25 ± 0.65 c | 4.62 ± 0.39 c | 11.28 ± 0.16 c | 18.28 | 47.43 ± 0.08 b | 5.89 ± 0.06 c | 14.74 ± 1.16c | 22.66 |

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE 100g−1 DM) | FRAP (μM TE 100 g−1 DM) | ABTS (μM TE 100g−1 DM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP0 | 29.08 ± 1.45 a | 199.72 ± 9.69 a | 240.00 ± 7.90 a |

| GP5 | 101.5 ± 7.68 b | 795.26 ± 63.11 b | 999.50 ± 24.78 b |

| GP10 | 207.06 ± 9.25 c | 1577.39 ± 87.20 c | 1540.83 ± 47.45 c |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tolve, R.; Simonato, B.; Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Giuberti, G. Wheat Bread Fortification by Grape Pomace Powder: Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010075

Tolve R, Simonato B, Rainero G, Bianchi F, Rizzi C, Cervini M, Giuberti G. Wheat Bread Fortification by Grape Pomace Powder: Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties. Foods. 2021; 10(1):75. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010075

Chicago/Turabian StyleTolve, Roberta, Barbara Simonato, Giada Rainero, Federico Bianchi, Corrado Rizzi, Mariasole Cervini, and Gianluca Giuberti. 2021. "Wheat Bread Fortification by Grape Pomace Powder: Nutritional, Technological, Antioxidant, and Sensory Properties" Foods 10, no. 1: 75. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10010075