Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

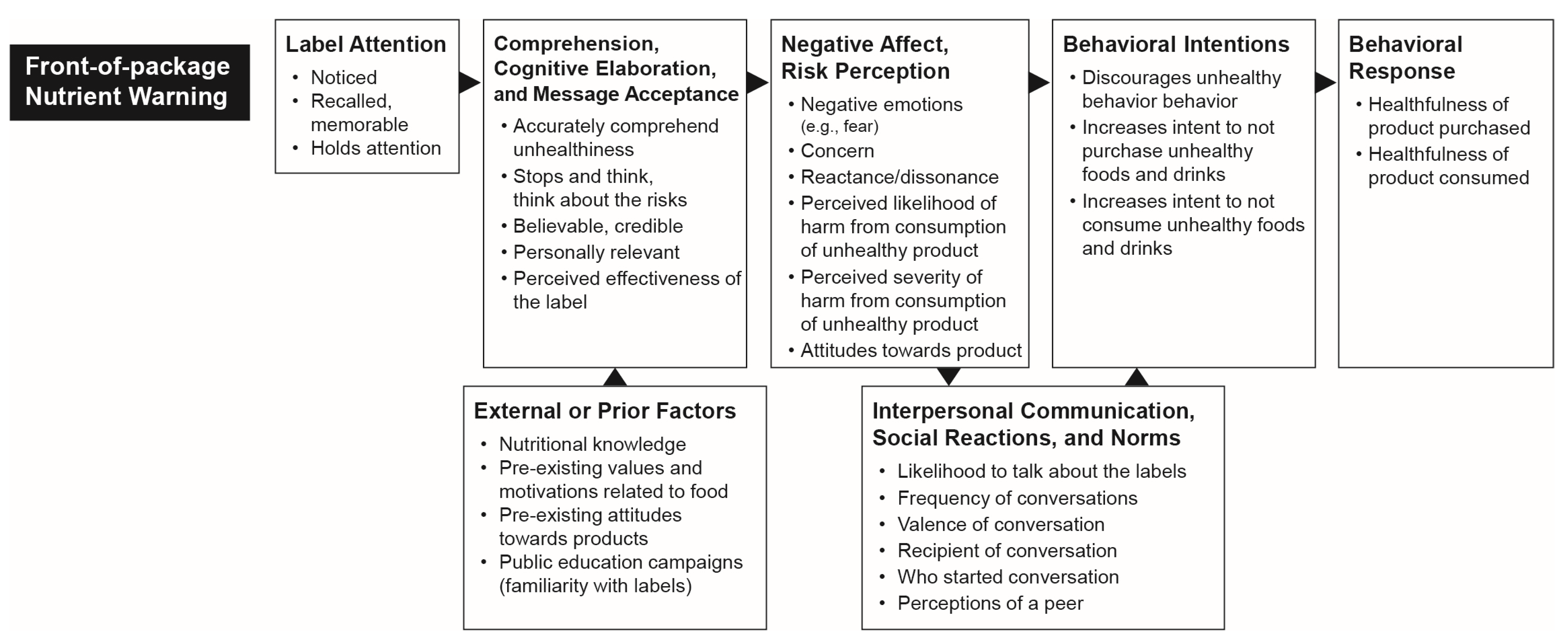

Conceptual Model

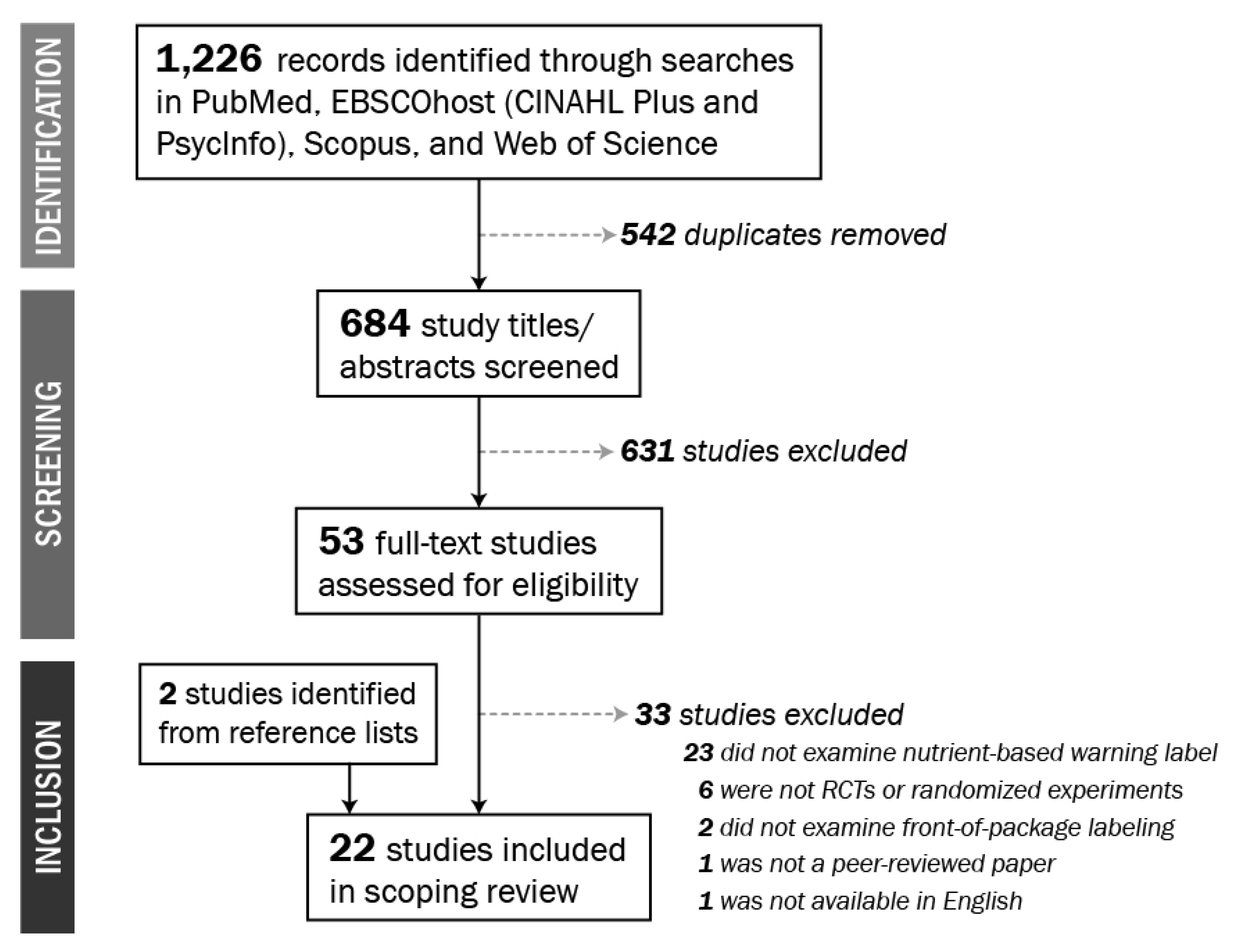

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vandevijvere, S.; Jaacks, L.M.; Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.; Girling-Butcher, M.; Lee, A.C.; Pan, A.; Bentham, J.; Swinburn, B. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B.M. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, R.D.D.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Hypertension in a Mediterranean Cohort: The Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra Project. Am. J. Hypertens. 2016, 30, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, R.D.D.; Pimenta, A.M.; Gea, A.; De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Lopes, A.C.S.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: The University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolet, T.; Srour, B.; Sellem, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Deschasaux, M.; Fassier, P.; Latino-Martel, P.; Beslay, M.; et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ 2018, 360, k322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Campà, A.; A Martínez-González, M.; Alvarez-Alvarez, I.; Mendonça, R.D.D.; De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Association between consumption of ultra-processed foods and all cause mortality: SUN prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019, 365, l1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, L.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Buscail, C.; Julia, C. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Risk of Mortality Among Middle-aged Adults in France. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.A.; Baker, P.I. Ultra-processed food and adverse health outcomes. BMJ 2019, 365, l2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Rojo, R.; Sandoval-Insausti, H.; López-Garcia, E.; Graciani, A.; Ordovás, J.M.; Banegas, J.R.; Artalejo, F.R.; Guallar-Castillon, P. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Mortality: A National Prospective Cohort in Spain. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 2178–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jackson, S.; Martinez, E.; Gillespie, C.; Yang, Q. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Cardiovascular Health Among US Adults: NHANES 2011–2016. Circulation 2019, 140, A10611. [Google Scholar]

- Rauber, F.; Campagnolo, P.; Hoffman, D.J.; Vitolo, M.R. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children’s lipid profiles: A longitudinal study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. 2015, 25, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjibade, M.; Julia, C.; Allès, B.; Touvier, M.; Lemogne, C.; Srour, B.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; Assmann, K.E.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Prospective association between ultra-processed food consumption and incident depressive symptoms in the French NutriNet-Santé cohort. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C.; Rauber, F.; Leffa, P.D.S.; Sangalli, C.; Campagnolo, P.; Vitolo, M.R. Ultra-processed food consumption and its effects on anthropometric and glucose profile: A longitudinal study during childhood. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.B.; Da Costa, T.H.M.; Da Veiga, G.V.; Pereira, R.A.; Sichieri, R. Ultra-processed food consumption and adiposity trajectories in a Brazilian cohort of adolescents: ELANA study. Nutr. Diabetes 2018, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Donoso, C.; Villegas, A.S.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Mendonça, R.D.D.; Lahortiga-Ramos, F.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of depression in a Mediterranean cohort: The SUN Project. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hu, E.A.; Rebholz, C.M. Ultra-processed food intake and mortality in the USA: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988–1994). Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, K.W.; Tinius, R.A.; Cade, W.T.; Steele, E.M.; Cahill, A.G.; Parra, D.C. Relationships between consumption of ultra-processed foods, gestational weight gain and neonatal outcomes in a sample of US pregnant women. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, F.; da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Steele, E.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic non-communicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients 2018, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Blanco-Rojo, R.; Graciani, A.; López-García, E.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Laclaustra, M.; Donat-Vargas, C.; Ordovás, J.M.; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F.; Guallar-Castillón, P. Ultra-processed food consumption and incident frailty: A prospective cohort study of older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.Y.; Chung, S.T.; Costa, E.; Courville, A.; Darcey, V.; et al. Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: A one-month inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrinis, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed foods and the limits of product reformulation. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colchero, M.A.; Popkin, B.M.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A.; Ng, S.W. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: Observational study. BMJ 2016, 352, h6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batis, C.; Rivera, J.A.; Popkin, B.; Taillie, L. First-year evaluation of Mexico’s tax on non-essential energy-dense foods: An observational study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, C.A.; Lawman, H.G.; Levasseur, M.T.; Mitra, N.; Peterhans, A.; Herring, B.; Bleich, S.N. Association of a Beverage Tax on Sugar-Sweetened and Artificially Sweetened Beverages With Changes in Beverage Prices and Sales at Chain Retailers in a Large Urban Setting. JAMA 2019, 321, 1799–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbe, J.; Thompson, H.R.; Becker, C.M.; Rojas, N.; McCulloch, C.E.; Madsen, K. Impact of the Berkeley Excise Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1865–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelvanovska, N.; Rogy, M.; Rossotto, C.M. Broadband Networks in the Middle East and North Africa: Accelerating High-Speed Internet Access. Economics 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvalán, C.; Reyes, M.; Garmendia, M.L.; Uauy, R. Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: Update on the Chilean law of food labelling and advertising. Obes. Rev. 2018, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, M. World Cancer Research Fund International (WCRF). Impact 2017, 2017, 32–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Philipsborn, P.; Stratil, J.M.; Burns, J.; Busert, L.K.; Pfadenhauer, L.M.; Polus, S.; Holzapfel, C.; Hauner, H.; Rehfuess, E. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and their effects on health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD012292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, R.A.; King, S.E.; Marteau, T.M.; Prevost, T.; Bignardi, G.; Roberts, N.W.; Stubbs, B.; Hollands, G.J.; Jebb, S.A. Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2, CD009315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shangguan, S.; Afshin, A.; Shulkin, M.; Ma, W.; Marsden, D.; Smith, J.; Saheb-Kashaf, M.; Shi, P.; Micha, R.; Imamura, F.; et al. A Meta-Analysis of Food Labeling Effects on Consumer Diet Behaviors and Industry Practices. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 56, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nancarrow, C.; Wright, L.T.; Brace, I. Gaining competitive advantage from packaging and labelling in marketing communications. Br. Food J. 1998, 100, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: A review. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Theoretical Foundations of Campaigns; Rice, R.E., Atkin, C.K., Eds.; Public communication campaigns; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelburg, Germany, 1986; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Southwell, B.; Yzer, M.C. The Roles of Interpersonal Communication in Mass Media Campaigns. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2007, 31, 420–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Zimmerman, R.S. Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: Are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Commun. Monogr. 1992, 59, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Hall, M.G.; Noar, S.M.; Parada, H.; Stein-Seroussi, A.; Bach, L.E.; Hanley, S.; Ribisl, K.M. Effect of Pictorial Cigarette Pack Warnings on Changes in Smoking Behavior: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, E.J.; White, K.; Fong, G.T.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Zanna, M.P.; Cameron, R. Enhancing the effectiveness of tobacco package warning labels: A social psychological perspective. Tob. Control 2002, 11, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormann, M.M.; Koch, C.; Rangel, A. Consumers can make decisions in as little as a third of a second. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2011, 6, 520–530. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C. Food packaging: The medium is the message. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Grebitus, C.; Nayga, R.M.; Verbeke, W.; Roosen, J. On the Measurement of Consumer Preferences and Food Choice Behavior: The Relation Between Visual Attention and Choices. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 538–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Boer, H.; Seydel, E.R. Protection motivation theory. In Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models; Open University Press: Berkshire, UK, 2005; pp. 81–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, M.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A.; MacLean, L.C.; Ziemba, W.T. Choices, Values, and Frames. In The Kelly Capital Growth Investment Criterion; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, A.J.; Salovey, P. Shaping perceptions to motivate healthy behavior: The role of message framing. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 121, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepitone, A.; Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Am. J. Psychol. 1959, 72, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A.; MacLean, L.C.; Ziemba, W.T. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. In The Kelly Capital Growth Investment Criterion; World Scientific Pub Co Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- University of Twente. Communication Theories. Available online: www.utwente.nl/communication-theories (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Morgan, J.C.; Golden, S.D.; Noar, S.M.; Ribisl, K.; Southwell, B.; Jeong, M.; Hall, M.G.; Brewer, N.T. Conversations about pictorial cigarette pack warnings: Theoretical mechanisms of influence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 218, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, J.F.; Abad-Vivero, E.N.; Huang, L.-L.; O’Connor, R.J.; Hammond, D.; Bansal-Travers, M.; Yong, H.-H.; Borland, R.; Markovsky, B.; Hardin, J.W. Interpersonal communication about pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages: Policy-related influences and relationships with smoking cessation attempts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 164, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariton, E.; Locascio, J.J. Randomised controlled trials—The gold standard for effectiveness research: Study design: Randomised controlled trials. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, M.; Machín, L.; Arrúa, A.; Antúnez, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Nutrition warnings as front-of-pack labels: Influence of design features on healthfulness perception and attentional capture. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 3360–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.; Hammond, D. Do manufacturer ‘nutrient claims’ influence the efficacy of mandated front-of-package labels? Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3354–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollard, T.; Maubach, N.; Walker, N.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Effects of plain packaging, warning labels, and taxes on young people’s predicted sugar-sweetened beverage preferences: An experimental study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrúa, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Rey, N.; Barreto, P.; Golovchenko, N.; Sellanes, A.; Velazco, G.; Winokur, M.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Impact of front-of-pack nutrition information and label design on children’s choice of two snack foods: Comparison of warnings and the traffic-light system. Appetite 2017, 116, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, B.; Crino, M.; Dunford, E.K.; Gao, A.; Greenland, R.; Li, N.; Ngai, J.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Pettigrew, S.; Sacks, G.; et al. Effects of Different Types of Front-of-Pack Labelling Information on the Healthiness of Food Purchases-A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.; Hammond, D. Do Consumers Think Front-of-Package “High in” Warnings are Harsh or Reduce their Control? A Test of Food Industry Concerns. Obesity 2018, 26, 1687–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.; Hammond, D. The impact of price and nutrition labelling on sugary drink purchases: Results from an experimental marketplace study. Appetite 2018, 121, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Objective Understanding of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels: An International Comparative Experimental Study across 12 Countries. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.; Vanderlee, L.; Acton, R.; Mahamad, S.; Hammond, D. The Impact of Front-of-Package Label Design on Consumer Understanding of Nutrient Amounts. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, N.; Sato, P.D.M.; Mais, L.A.; Martins, A.P.B.; Spinillo, C.G.; Garcia, M.T.; Rojas, C.F.U.; Jaime, P.C. Are Front-of-Package Warning Labels More Effective at Communicating Nutrition Information than Traffic-Light Labels? A Randomized Controlled Experiment in a Brazilian Sample. Nutrients 2018, 10, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. How do front of pack nutrition labels affect healthfulness perception of foods targeted at children? Insights from Brazilian children and parents. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 64, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machín, L.; Arrúa, A.; Giménez, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Martínez, J.; Ares, G. Can nutritional information modify purchase of ultra-processed products? Results from a simulated online shopping experiment. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machín, L.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Curutchet, M.R.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Does front-of-pack nutrition information improve consumer ability to make healthful choices? Performance of warnings and the traffic light system in a simulated shopping experiment. Appetite 2017, 121, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acton, R.; Jones, A.C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Roberto, C.A.; Hammond, D. Taxes and front-of-package labels improve the healthiness of beverage and snack purchases: A randomized experimental marketplace. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, F.J.L.; Agrawal, S.; Finkelstein, E.A. Pilot randomized controlled trial testing the influence of front-of-pack sugar warning labels on food demand. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grummon, A.H.; Hall, M.G.; Taillie, L.S.; Brewer, N.T. How should sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings be designed? A randomized experiment. Prev. Med. 2019, 121, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandpur, N.; Mais, L.A.; Sato, P.D.M.; Martins, A.P.B.; Spinillo, C.G.; Rojas, C.F.U.; Garcia, M.T.; Jaime, P.C. Choosing a front-of-package warning label for Brazil: A randomized, controlled comparison of three different label designs. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, M.; De Alcantara, M.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. It is not all about information! Sensory experience overrides the impact of nutrition information on consumers’ choice of sugar-reduced drinks. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.; De Alcantara, M.; Martins, I.B.; Ares, G.; Deliza, R. Can front-of-pack nutrition labeling influence children’s emotional associations with unhealthy food products? An experiment using emoji. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machín, L.; Curutchet, M.R.; Giménez, A.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Ares, G. Do nutritional warnings do their work? Results from a choice experiment involving snack products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 77, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Gombaud, M.; Galán, P.; Hercberg, S.; Pettigrew, S.; Julia, C. Consumers’ Responses to Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Results from a Sample from The Netherlands. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talati, Z.; Egnell, M.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C.; Pettigrew, S. Consumers’ Perceptions of Five Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels: An Experimental Study Across 12 Countries. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, G.; Varela, F.; Machín, L.; Antúnez, L.; Giménez, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Comparative performance of three interpretative front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes: Insights for policy making. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egnell, M.; Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C. Comparison of front-of-pack labels to help German consumers understand the nutritional quality of food products. Color-coded labels outperform all other systems. Ernahr. Umsch. 2019, 66, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.M.; Ranney, L.M.; Pepper, J.K.; Goldstein, A.O. Source Credibility in Tobacco Control Messaging. Tob. Regul. Sci. 2016, 2, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.; Maloney, E.; Ophir, Y.; Cappella, J.N. Designing Effective Testimonial Pictorial Warning Labels for Tobacco Products. Health Commun. 2018, 34, 1383–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, H.; Meloncelli, N.; Pelly, F. Nutritional quality and reformulation of a selection of children’s packaged foods available in Australian supermarkets: Has the Health Star Rating had an impact? Nutr. Diet. 2018, 76, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonté, M.-E.; Poon, T.; Gladanac, B.; Ahmed, M.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Rayner, M.; L’Abbé, M. Nutrient Profile Models with Applications in Government-Led Nutrition Policies Aimed at Health Promotion and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 741–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Plazas, M.; Gómez, L.F.; Miles, D.; Parra, D.C.; Taillie, L.S. Nutrition Quality of Packaged Foods in Bogotá, Colombia: A Comparison of Two Nutrient Profile Models. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, A.C.; Ricardo, C.Z.; Mais, L.A.; Martins, A.P.B. Role of different nutrient profiling models in identifying targeted foods for front-of-package food labeling in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Soares-Wynter, S.; Aiken-Hemming, S.-A.; Hollingsworth, B.; Miles, D.; Ng, S.W. Applying Nutrient Profiling Systems to Packaged Foods and Drinks Sold in Jamaica. Foods 2020, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrasher, J.F.; Murukutla, N.; Pérez-Hernández, R.; Alday, J.; Arillo-Santillán, E.; Cedillo, C.; Gutierrez, J.P. Linking mass media campaigns to pictorial warning labels on cigarette packages: A cross-sectional study to evaluate effects among Mexican smokers. Tob. Control 2012, 22, e57–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, E.; Durkin, S.; Cotter, T.; Harper, T.; Wakefield, M.A. Mass media campaigns designed to support new pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets: Evidence of a complementary relationship. Tob. Control 2011, 20, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| % 2 | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| Latin America | 55% | 12 |

| US/Canada | 32% | 7 |

| UK/Europe/Australia/New Zealand | 32% | 7 |

| Asia | 5% | 1 |

| Setting | ||

| Online | 64% | 14 |

| Laboratory | 18% | 4 |

| Retail store | 5% | 1 |

| School | 18% | 4 |

| Age Group | ||

| Children (≤13 years) | 18% | 4 |

| Adolescents (13–18 years) | 18% | 4 |

| Adults (18+ years) | 91% | 20 |

| Sex (average % female) 3 | ||

| Children (≤13 years) | 49% (±1%) | |

| Adolescents and adults | 61% (±13%) | |

| Education | ||

| Reported educational attainment | 68% | 15 |

| Reported school type (public or private) | 18% | 4 |

| % examining education as modifier/stratifier | 14% | 3 |

| Nutrient Warnings Shape | ||

| Rectangle | 9% | 2 |

| Circle | 14% | 3 |

| Octagon | 77% | 17 |

| Triangle | 18% | 4 |

| Magnifying glass w/exclamation | 5% | 1 |

| Other | 9% | 2 |

| Nutrient Included in Warning, % | ||

| Sugar | 91% | 20 |

| Saturated fat | 55% | 12 |

| Total fat | 14% | 3 |

| Sodium | 59% | 13 |

| Calories | 32% | 7 |

| Other | 9% | 2 |

| Outcome Category, % | ||

| Attention | 23% | 5 |

| Comprehension | 50% | 11 |

| Cognitive elaboration and message acceptance | 36% | 8 |

| Negative affect and risk perception | 18% | 4 |

| Behavioral intentions | 41% | 9 |

| Behavioral response | 23% | 5 |

| Other | 14% | 3 |

| Comparison FoP Label % | ||

| Multiple traffic light label | 59% | 13 |

| Health Star Rating | 41% | 9 |

| Guideline Daily Amount (or similar) | 32% | 7 |

| Nutri-score | 23% | 5 |

| Health warnings (graphic or text) | 23% | 5 |

| Control (no FoP label or neutral label) | 54% | 12 |

| Study | Setting | Population | Design | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bollard et al., 2016 [59] | Online | New Zealand Adolescents/young adults age 13–24 years; n = 604 | 2 × 3 × 2 between-group: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Attitudes towards the product Social norms: Perceptions of a peer if they were drinking from the displayed can Attitudes towards policy Behavioral intentions: intentions to purchase. |

| Arrúa et al., 2017 [60] | School | Montevideo, Uruguay Children age 8–13 years; n = 442; | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 2 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Behavioral intentions: children’s choice of product (images of product). |

| Neal et al., 2017 [61] | Stores | Australia Adults age 18+ years; n= 1578 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: Nutrition information panel | Behavior: nutrient profile of food purchases. Elaboration and message acceptance: usefulness of the label; usefulness of having the label printed on every package. Comprehension: ease of understanding the label; current nutrition knowledge. |

| Acton and Hammond, 2018 [62] | Online | Canada Adolescents/young adults age 16–32 years; n = 1000 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: None | Elaboration and message acceptance: perceptions of whether the label is harsh enough Self-efficacy: assessment of being in control of making healthy decisions? |

| Acton and Hammond, 2018 [63] | Lab | Canada Adolescents and adults age ≥16 years; n = 675 | Between person: randomized to 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: no label | Behavior: purchase of beverage. |

| Egnell et al., 2018 [64] | Online | Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States Adults age ≥18 years; n = 12,015 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 5 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Comprehension: ranking of products according to nutritional quality. |

| Goodman et al., 2018 [65] | Online | Canada, United States, Australia, United Kingdom Adults age 18–64 years; n = 11,617 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 11 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Comprehension: identification of whether a product contained high, moderate, or low amounts of sugar or saturated fat. Elaboration and message acceptance: selection of the best symbol for informing consumers that a product is “high in” saturated fat and sugar. |

| Khandpur et al., 2018 [66] | Online | Brazil Adults age ≥18 years; n = 1607 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 2 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Visibility/attention: rating of visibility and attention. Comprehension: identification of products high in nutrients of concern; ability to identify healthy products, rating of products’ healthfulness. Message acceptance: rating of credibility, usefulness, and ease of use. Behavioral intentions: likelihood of purchasing this or similar product. |

| Lima, Ares, and Deliza, 2018 [67] | Schools (children) Online (parents) | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Children age 6–9 years and 9–12 years; stratified by public and private schools Adults age ≥18 years, n = 278 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: none | Comprehension: rating of product healthfulness. Attitudes towards product: rating of perceived ideal consumption by children. |

| Machín et al., 2017 [68] | Online (simulated online grocery store) | Uruguay Adults age ≥18 years; n = 437 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: no label | Behavioral intentions: share of intended ultra-processed food purchases; healthfulness of intended purchases. |

| Machín et al., 2018 [69] | Online (simulated online grocery store) | Uruguay Adults age ≥18 years;n = 1182 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: No FoP label | Behavioral intentions: healthfulness of intended food purchases. |

| Acton et al., 2019 [70] | Lab | Canada Adolescents and adults age ≥13 years; n = 3584 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 5 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Attention: noticing the FoP warning label. Behavior: healthfulness of beverage purchases. |

| Ang, Agrawal, and Finkelstein, 2019 [71] | Online (simulated online grocery store) | Singapore Adults age ≥21 years; n = 512 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Behavioral intentions: healthfulness of intended purchases. |

| Grummon et al., 2019 [72] | Online | United States Adults age ≥18 years; n = 1360 | Between subjects: randomized between 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: control FoP label | Perceived message effectiveness: rating of concern about health effects of, unpleasantness of, and discouragement from drinking beverages with added sugar. Affect: rating of thinking about the health problems caused by beverages with added sugar and how much the label made them feel scared. Comprehension: knowledge of health harms of SSB consumption. |

| Khandpur et al., 2019 [73] | Online | Brazil adults (ages not stated) n = 2419 | Between participants: randomized to 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Attention: rating of label visibility. Comprehension: identification of products high in or higher in nutrients of concern; identification of products not high in nutrients of concern; identification of healthier product, rating of product healthfulness. Behavioral intentions: likelihood of buying a product. Message acceptance: perceptions of label effects on behavior, understanding, helpfulness, and visibility. |

| Lima et al., 2019 [74] | School (children) Lab (parents) | Brazil Children age 6–12 years; n = 400 Adults age 18–65 years; n = 400 | Between subjects: randomized to 1 of 2 FoP labels Control: within-person | Behavior: selection of product to consume (regular-sugar version, the slightly reduced sugar version, or the highly reduced sugar version). |

| Lima et al., 2019 [75] | School | Rio de Janeiro, Rio Pomba, Brazil Children age 6–12 years; n = 492 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 3 FoP labels Control: none | Affect: rating of feelings when eating the product (e.g., selection of emojis with the corresponding expression). |

| Machín et al., 2019 [76] | Lab | Uruguay Adults age ≥18 years; n = 199 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 2 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Attention: fixations on nutritional warnings Behavior: selection of a snack. |

| Egnell et al, 2019 [77] | Online | The Netherlands Adults age ≥18 years; n = 1032 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 5 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Comprehension: ranking of products according to their nutritional quality Message acceptance: ratings of liking, awareness, perceived cognitive workload. Behavioral intentions: likelihood of purchasing a product. |

| Talati et al, 2019 [78] | Online | Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Mexico, Singapore, Spain, the UK, and the USA Adults age ≥18 years; n = 12,015 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 5 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Attention: rating of whether label stands out. Comprehension: rating of whether label is easy to understand, took too long to understand, is confusing, and provides needed information. Message acceptance: participants rated how much they liked the label, trusted, the label, and whether label should be compulsory. |

| Ares et al, 2018 [79] | Online | Uruguay Adults age ≥18 years; n = 892 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 4 FoP labels Control: no FoP label | Comprehension: rating of product healthfulness. Behavioral intentions: likelihood of purchasing product. |

| Egnell et al, 2019 [80] | Online | Germany Adults age ≥18 years; n = 1000 | Between-person: randomized to 1 of 5 FoP labels Control: no FoP label (within-person) | Comprehension: ranking of products according to their nutritional quality. |

| Study | Results |

|---|---|

| Bollard et al., 2016 [59] | Attitudes: Nutrient warnings (vs. control) had a negative effect on product preferences. Graphic warnings impacted product preferences more than nutrient warnings. Attitudes towards policy: More participants (66%) agreed or strongly agreed that SSBs should carry a (text) nutrient warning compared to graphic warning labels (50%). Behavioral intentions: Graphic warning and nutrient warnings decreased likelihood of intentions to purchase SSBs. |

| Arrúa et al., 2017 [60] | Behavioral intentions: For both product types, nutrient warnings discouraged children’s choice of product more than traffic light labels did. |

| Neal et al., 2017 [61] | Behavior: Compared to the control label, nutrient warnings led to healthier food purchases, but Health Star Ratings and Daily Intake Guides did not. Elaboration and message acceptance: There were no differences in ratings of how useful the labels were. Health Star Ratings were rated as more useful to have printed on every food package than were nutrient warnings. Comprehension: There were no differences between the Health Star Rating and nutrient warnings for consumers’ perception of their current nutrition knowledge. There were no differences in how easy the labels were to understand. |

| Acton and Hammond, 2018 [62] | Elaboration and message acceptance: Across all label conditions, at least 88% of respondents indicated the labels were “about right” or “not harsh enough.” Participants viewing the Health Star Rating were more likely to rate the symbol as not harsh enough compared with those who viewed any of the three nutrient warnings. Self-efficacy: Across all label conditions, 83% reported that the labels made them feel more in control or neither more/less in control. Participants viewing the Health Star Rating were less likely to state that the symbol made them feel more in control compared with those who viewed any of the three nutrient warnings. |

| Acton and Hammond, 2018 [63] | Behavior: There was no statistically significant effect of labeling, though there was a trend for the “high sugar” nutrient warnings to reduce the likelihood to purchase a sugary drink and encourage participants to purchase drinks with less sugar. |

| Egnell et al., 2018 [64] | Comprehension: All labels improved the number of correct responses in the ranking task. Nutri-score elicited the largest increase in the number of correct responses, followed by the multiple traffic light label, the Health Star Rating, nutrient warnings, and the reference intakes. |

| Goodman et al., 2018 [65] | Comprehension: Participants who viewed the red stop sign, caution triangle and exclamation mark, red circle, or magnifying glass + exclamation mark with high-in text were more likely to correctly identify the cereal as high-in saturated fat and sugar compared to those who saw the no-FoP control, with the highest odds observed among participants who viewed the red stop sign with the text “high-in” and the caution triangle, exclamation mark, and the text “high in.” Across all designs, respondents who viewed nutrient warnings with “high in” text had greater odds of responding correctly. Elaboration and message acceptance: Participants most often selected the red stop sign as the best nutrient warning symbol for informing consumers, followed by the triangle and exclamation mark. |

| Khandpur et al., 2018 [66] | Visibility/attention: Compared to participants who viewed traffic light labels, participants who viewed nutrient warnings rated the labels as having higher visibility and drawing more attention. Comprehension: Compared to when they viewed the no-label control, participants who viewed products with nutrient warnings improved their ability to identify products with excess nutrient content, improved their ability to identify healthy products, and decreased their perceptions of product healthfulness more than those who viewed traffic light labels. Behavioral intentions: Relative to when they viewed the no-label control condition, compared to participants who viewed traffic light labels, the participants who viewed products with nutrient warnings were more likely to express intent to buy the healthier product or neither products. Message acceptance: Compared to participants who viewed traffic light labels, participants who viewed nutrient warnings rated the labels as having higher credibility, usefulness, and ease of use. |

| Lima, Ares, and Deliza, 2018 [67] | Comprehension: There was no effect of labels on 6–9-year-old children or 9–12-year-old children from public schools. For 9–12-year olds from private schools, children who viewed nutrient warnings or traffic light labels rated the products as having lower healthfulness than children who viewed the GDA. Parents who viewed nutrient warnings rated the products as having lower healthfulness than parents who viewed the GDA. There were no differences in healthfulness ratings for the traffic light condition. Attitudes towards product: For parents with children in public schools, parents who viewed nutrient warnings rated products as having a lower ideal consumption frequency for specific products, including gelatin (compared to parents who viewed the GDA label) and corn snacks (compared to parents viewed the traffic light label). |

| Machín et al., 2017 [68] | Behavioral intentions: Overall, there were no differences between labeling conditions for mean share of intended ultra-processed food purchases or in mean nutrient content of intended food purchases. Participants in the nutrient warning condition decreased intended purchases of sweets and desserts. |

| Machín et al., 2018 [69] | Behavioral intentions: Compared to the control group, participants in both the nutrient warning condition and traffic light label condition decreased the average purchased density of calories, sugars, and saturated fats. Sodium density of purchases was also significantly decreased in the nutrient warning group compared to the control. Compared to the control group, participants in both the nutrient warning condition and traffic light label condition intended to purchase lower total amounts of calories, sugar, saturated fat, and sodium, though there were no statistically significant differences between the traffic light label and nutrient warning conditions. Compared to the control group, participants in both the nutrient warning condition and traffic light label condition purchased fewer products that were high in at least one nutrient. Compared to the control group, participants in both the nutrient warning condition and traffic light label condition spent less money on products in the categories: juice, cheese, bouillon cubes, spices, cereal bars, crackers, sweet cookies, cocoa, cream cheese, yogurt, nuts, jams, and ice creams. Participants in the traffic light label condition also decreased expenditures on oils. |

| Acton et al., 2019 [70] | Attention: A higher proportion of participants noticed the nutrient warnings than did participants in other labeling conditions. Behavior: For beverages, participants in the nutrient warning condition purchased beverages containing less sugar, saturated fat, and calories compared to those in the no-label control. There were no significant differences in the amount of sodium purchased between conditions. For foods, participants in the nutrient warning condition and traffic light label condition purchased foods with less sodium and fewer calories compared to the no label condition. Participants in the traffic light label condition also purchased less sodium and calories than those in the nutrition grade condition. Participants who viewed the Health Star Rating purchased fewer calories than those in the no label control condition. There were no significant differences in the amount of sugar or saturated fat purchased between conditions. |

| Ang, Agrawal, and Finkelstein, 2019 [71] | Behavioral intentions: Participants in the nutrient warning and health warning label conditions purchased a lower proportion of high-in-sugar products than those in the control, but this was statistically significant only for the health warnings. There were no differences between the nutrient warning and health warning groups. There were no differences between any group for total sugar purchased, sugar purchased per dollar spent, total spending, or total expenditure on high-sugar products. Results restricted to beverage only followed the same pattern as for total purchases. |

| Grummon et al., 2019 [72] | Perceived message effectiveness: Warnings that included health effects were perceived as more effective than those without health effects. Nutrient warnings were perceived as more effective than those without, though the effect was not as strong as for health warnings. Perceived message effectiveness was higher for warnings that included the marker word vs. those that did not, and for those that displayed an octagon vs. a rectangle-shaped label. Affect: Health effects had the biggest impact on thinking about harms and fear; nutrient disclosures also increased thinking about harms and fear. Thinking about harms and fear was higher for warnings that included the marker word vs. those that did not, and for those that displayed an octagon vs. a rectangle-shaped label. Comprehension: Nutrient warnings did not impact knowledge of health effects of SSB consumption. Health warnings increased knowledge that SSB intake leads to tooth decay, had no effect on knowledge that SSBs contribute to obesity or diabetes, and led to lower knowledge that SSBs contribute to heart disease. |

| Khandpur et al., 2019 [73] | Attention: Participants who viewed a nutrient warning triangle with the text “a lot of” rated the labels as more visible than participants who viewed the nutrient warning octagon. Comprehension: Participants in all nutrient warning conditions had higher scores for identifying nutrients in excess compared to participants in the control arm. Participants in the triangle “high in” condition correctly identified the most nutrients in excess. There were no differences between the nutrient warning conditions and the control for identifying nutrients not in excess. Participants in the triangle “high in” condition were the most likely to correctly select the product of a pair with the higher content of a nutrient of concern. Participants in the triangle “high in” condition and the triangle “a lot of” condition were most likely to correctly identify the overall healthier product out of the pair. Participants in all nutrient warning conditions had higher mean perceptions of levels of nutrients of concern than the control, and there were no differences between nutrient warnings. Participants in the triangle “high in” had the highest mean perception of nutrient levels. Participants in all nutrient warning conditions rated products as less healthy than the control, with no differences between types of nutrient warnings. Participants in the triangle “high in” had the lowest mean ratings of healthfulness. Behavioral intentions: Participants in all nutrient warning conditions expressed lower intentions to purchase than did participants in the control condition. Participants in the triangular “high in” condition expressed the lowest intentions to purchase. Message acceptance: Participants in all nutrient warning conditions had similar opinions on the effects of labels on improving purchasing and eating behaviors, the labels’ helpfulness, credibility, and ease of understanding. |

| Lima et al., 2019 [74] | Behavior: For adults and children, there was no effect of label type on selection of chocolate milk sample overall or by scenario (blind, expected, informed). For children, there was also no effect of label type on selection of grape nectar sample overall or by scenario. For adults, there was no effect on selection of grape nectar sample overall or by condition, except in the expected condition. In the expected condition, adults who were randomized to the nutrient warning condition were more likely to choose the highly reduced sugar sample (i.e., the only sample without a warning label) than were participants in the traffic light condition. |

| Lima et al., 2019 [75] | Affect: Children who were randomized to the nutrient warning and traffic light label conditions used emojis associated with positive emotions less frequently than children who were randomized to the GDA condition. The nutrient warning tended to have a greater effect on emoji use than the traffic light label. For some emojis, children from public schools tended to show greater changes in emoji use in response to the nutrient warning and traffic light label. |

| Machín et al., 2019 [76] | Attention: In total, 50% of the participants who were randomized to see the nutrient warning fixated their gaze on the warning for at least one product. Behavior: Participants in the nutrient warning condition were less likely to select products with excessive content of at least one nutrient, compared to the control group. |

| Egnell et al., 2019 [77] | Comprehension (objective understanding): Relative to the reference intakes, across all food categories, participants in the Nutri-score condition increased their ability to correctly rank the healthfulness of products the most compared to the no-label control condition. Participants in the nutrient warning and traffic light label conditions increased their ability to correctly rank cakes. Message acceptance: There were few differences in overall perceptions of labels. Behavioral intentions: Relative to the reference intake, there was no association between label type and change in nutritional quality of the product participants intended to purchase compared to the no label condition, overall and by food category. The exception was that participants in the nutrient warning condition were more likely to select a healthier breakfast cereal. |

| Talati et al., 2019 [78] | Attention: When asked to rate whether a label “did not stand out”, participants rated reference intakes the highest, followed by nutrient warning and Health Star Ratings. Nutri-score scored the lowest for not standing out. Comprehension: Participants rated nutrient warnings the lowest for “taking too long to understand,” and reference intakes the highest. Participants rated nutrient warnings as the highest for “easy to understand,” while Nutri-score scored the lowest. Participants scored traffic light labels the highest on providing all the information that they need, while Nutri-score was scored the lowest and nutrient warnings the second-lowest. Message acceptance: Participants rated the traffic light label the highest for liking and trust, with nutrient warnings scoring the lowest and second lowest on these items, respectively. Participants scored the traffic light label highest for being compulsory; Nutri-score scored the lowest and nutrient warnings the second-lowest. |

| Ares et al., 2018 [79] | Comprehension: The nutrient warnings had the greatest impact on perceptions of healthfulness and reduced perceived healthfulness compared to the control for cereals, yogurt, orange juice, bread, and mayonnaise. The Health Star Rating had the lowest impact on healthfulness perceptions. Behavioral intentions: Nutrient warnings had the greatest impact on purchase intentions, leading to decreased intentions to purchase breakfast cereals, yogurt, bread, and mayonnaise, compared to the control. Nutri-score reduced intentions to purchase only breakfast cereals and mayonnaise, while the Health Star Rating did not impact purchase intentions for any products. |

| Egnell et al., 2019 [80] | Comprehension: All labels improved the percentage of correct answers in the ranking exercise compared to the no-label control. Across categories, nutrient warnings were not associated with an increased likelihood in ability to correctly rank products, with the exception that nutrient warnings increased this likelihood for the cake category. Nutri-score was associated with the highest increase in ability to correctly rank products. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taillie, L.S.; Hall, M.G.; Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W.; Murukutla, N. Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020569

Taillie LS, Hall MG, Popkin BM, Ng SW, Murukutla N. Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2020; 12(2):569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020569

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaillie, Lindsey Smith, Marissa G. Hall, Barry M. Popkin, Shu Wen Ng, and Nandita Murukutla. 2020. "Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 12, no. 2: 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020569

APA StyleTaillie, L. S., Hall, M. G., Popkin, B. M., Ng, S. W., & Murukutla, N. (2020). Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 12(2), 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020569