3.1. The Relationship between Servant Leadership, and Employee Satisfaction and Retention

The concept of servant leadership, even if it was not labelled as such, dates back several centuries [

30]. Greenleaf [

31] (p. 29) defined servant leaders as “servant first” and described the process as beginning “with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, and then the conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead.” Servant leadership positively and significantly contributes to organizational success and increases followers’ personal growth [

2,

9]. In empirical studies, it has a significant impact on organizations’ performances; for instance, Jones [

32] found a positive relationship between servant leadership and organizations’ performances. Baykal at al. [

33] and Peterson et al. [

34] also showed that servant leadership was of paramount importance to improving an organization and argued it was essential to organizational sustainability [

12]. Moreover, studies have revealed the significant effects of servant leadership on individual performance levels. For example, Donia et al. [

35] found that it enhanced the level of satisfaction among supervisors in a service industry (communication and banking) organization in Pakistan. Additionally, Sepahvand et al. [

36] and Rozika et al. [

37] indicate that it is related to satisfaction. Moreover, Hunter et al. [

38] and Jaramillo et al. [

39] reported that it is positively related to a reduced employee turnover intention rate, and Wong et al. [

40] and Brohi et al. [

41] showed that it is positively associated with retention. Taking into consideration the high value placed on serving others in the cultural context of Jordan, we expect that employees will be more satisfied and more likely to stay with their organization if they see that their leaders are interested in the benefits of the group more than their own leadership status. This interest will result in the sustainability of the organization. Thus, the study proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a). Servant leadership has a positive effect on employee satisfaction;

Hypothesis 1b (H1b). Servant leadership has a positive effect on employee retention.

3.2. The Relationship between HPWS, and Employee Satisfaction and Retention

The increasing popularity of HPWS can be attributed to the recognition of people as the most important source of competitive advantage [

42,

43,

44], and the most critical aspect of human effort is to achieve sustainable results [

23]. This study uses the term HPWS [

45], but the concept has also been discussed by several authors using terms ranging from [

46], high-performance work practices [

47], high commitment work systems [

48], high-performance human resource management [

49], and system human resource management [

50]. Scholars define HPWS as a mixture of HR practices that improve employee skills and motivations, impacting employee attitudes and outcomes [

51,

52]. Thus, HPWS is “designed to enhance employees’ skills, commitment, and productivity in such a way that employees become a source of sustainable competitive advantage” which aids in organizational sustainability [

42] (p. 138).

The relationship between HPWS practices and organizational performance can be developed via the precepts of resource-based view (RBV) theory. Specifically, RBV theory proposes that organizations must identify and utilize their unique resources that are not easily imitated by the competition and use these resources as their competitive advantage. HPWS helps to identify and invest in the human capital and helps to achieve higher levels of organizational performance [

53]. Previous empirical studies on HPWS and its impact on organizational performance can be classified into three categories. The first category shows how the HPWS practices as a bundle have an impact on overall organizational performance [

49,

54,

55]. The second category of studies reveals the influence of individual HPWS practices, such as recruitment and selection [

56,

57], training and development [

58,

59], compensation and rewards [

60,

61], and performance appraisal [

62] on organizational performance. The third category of studies shows the effects of HPWS practices on certain indicators of organizational performance, such as job satisfaction [

63,

64,

65], employee engagement [

66,

67,

68], and employee retention [

69,

70].

A study of a power company in India, Muduli [

71] demonstrated the positive associations between six HPWS practices (i.e., staffing, compensation, flexible job assignments, teamwork, training, and communication) and organizational performance. Jyoti and Rani [

45] also noted that HPWS fostered organizational performance by providing a good working environment for both the employees and the community in a telecommunication organization. Based on their results, Katou and Budhwar [

72] advocated a positive influence of HPWS practices on organizational performance through recruitment, training, promotion, incentives, benefits, involvement, health, and safety. Additionally, in a study of employees working in the hotel sector in India, Chand, and Katou [

73] claimed that recruitment and selection, manpower planning, job design, training and development, quality circles, and pay systems were positively associated with better hotel performance.

In the same vein, there is evidence that HPWS influences employee satisfaction: García-Chas et al. [

65] showed that HPWS was of paramount importance for improving satisfaction in a variety of sectors in Spain. Another influential role of HPWS is to help employees solve problems they face in their jobs and gain new knowledge to increase productivity [

45]. Consistent with this role, Haider et al. [

74] stated that HPWS practices support employee retention. Similarly, Azeez [

75] indicated that HPWS practices, such as leadership, rewards, salary, compensation, training and development, career development, and recognition are influential for job satisfaction and lower turnover. Hong et al. [

76] stressed that HPWS practices, namely training and development, appraisal systems, and compensation, positively affect retention. With an economy open to competition, airlines in Jordan need to utilize their human resources in the best way in order to develop a competitive advantage. Based on the above arguments, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). The HPWS practices of selection and recruitment, training and development, performance appraisals, and compensation, have positive effects on employee satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). The HPWS practices of selection and recruitment, training and development, performance appraisals, and compensation, have positive effects on employee retention.

3.3. The Relationship between Employee Engagement, and Employee Satisfaction and Retention

Employee engagement has also been discussed [

77], said to include work engagement [

78] and personal engagement [

79], and is seen as a critical factor in many employee outcomes. Robinson et al. [

80] described employee engagement as a positive employee attitude on the job that creates commitment to the organization and leads to improved organizational performance and effective achievement of the organization’s goals [

81]. Karatepe [

78], Harter et al. [

82], and Saks [

52] also contended that engagement plays a vital role in improving organizational performance. According to Truss et al. [

83] and Kaliannan and Adjovu [

84], employee engagement supports organizational success by enhancing competitive advantage. Studies have also provided evidence that employee engagement enhances organizational performance. For example, Demerouti and Cropanzano [

13] demonstrated that employee engagement positively influences organizational performance. Furthermore, Baumruk [

85] indicated that employee engagement promotes teamwork and job sharing, leading to attainment of the organization’s goals and sustainability. In a study of employees in the hotel sector, Kim and Koo [

86] found that engagement fostered organizational performance. Some empirical studies have found significant relationships of engagement with satisfaction and retention, as measures of individual performance. For example, Alarcon and Lyons [

87], Rayton and Yalabik [

88] reported that employee engagement positively influences employee satisfaction. Moreover, Bhatnagar [

89] showed that employee engagement increased retention in an information technology enabled service (ITES) organization in India. More recently, Kundu and Lata [

90] reported that employee engagement enhances retention in both public and private sector organizations. Given these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a). Employee engagement has a positive effect on employee satisfaction;

Hypothesis 3b (H3b). Employee engagement has a positive effect on employee retention.

3.4. Employee Engagement as a Mediator between HPWS Practices, and Employee Satisfaction and Retention

Social exchange theory (SET) argues that individuals assess what they give and what they receive in a relationship and they are satisfied if they perceive that there is a fair exchange. Thus, it serves as a viable theoretical framework to examine how HPWS practices and organizational performance are related [

91]. The employees perceive the high-performance practices—such as training—as investment in their skills, and the performance appraisal and rewards systems as recognition for their achievements. The employees also consider the recruitment and selection systems as the importance the organization places on them. Thus, they feel that the relationship that they have with the organization is not merely a simple transaction but a fair social exchange that is based on an ongoing relationship [

91]. Therefore, the HPWS practices play a vital role in improving the level organizational performance through the increased employee engagement with the organization. For example, the level of employee engagement with organization increases by providing training programs to improve employees’ skills and knowledge that positively affect their performance. According to Zacharatos et al. [

92], the main purpose of HPWS is to engage employees in decision making by empowering them in an organization that enhances employee trust and efficiency.

Considering the relationship between HPWS practices and employee engagement, a number of empirical studies have asserted a link between these constructs. For example, Davies et al. [

93] indicated that HPWS practices, such as training and development, influence employee engagement. Karatepe [

78] showed that training, empowerment, and reward systems boosted engagement among employees in the hotel sector. Presbitero [

68] found that HPWS practices, such as training and development, and rewards, positively influenced engagement in the Philippines’ hotel sector. In concordance with these findings, Ling Suan et al. [

94] showed that training and performance appraisals enhanced employee engagement in the Malaysian hotel sector. In addition, Juhdi et al. [

95] reported that HPWS practices, such as compensation, rewards, development opportunities, career management, personal–job fit, and job control positively influenced employee engagement. Furthermore, Babakus et al. [

96] demonstrated that training, empowerment, and rewards improved work engagement and reduced turnover intentions, leading to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The HPWS practices of selection and recruitment, training and development, performance appraisals, and compensation have positive effects on employee engagement.

There is evidence that employee engagement plays a mediating role in multiple relationships. For example, Schaufeli and Salanova [

97] reported that engagement fully mediates the effect of job resources on proactive behavior. Similarly, in a study of the banking sector in the UK, Yalabik et al. [

98] showed that it plays a mediating role in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee performance. Moreover, Karatepe and Aga [

99] found that employee engagement fully mediates the relationships of organizational mission fulfillment and perceived organizational support with job performance, among frontline employees in banks in Northern Cyprus. Moreover, empirical research has revealed that engagement plays a mediating role between HPWS practices and organizational performance. For example, Karatepe and Olugbade [

67] contended that HPWS practices, such as selective staffing, job security, teamwork, and career opportunities, impact job outcomes through employee engagement. Similarly, Karatepe [

78] found that engagement (i.e., vigor, dedication, and absorption) fully mediates the relationship between HPWS practices (i.e., training, empowerment, and rewards) and job and extra-role performance.

Based on the social exchange theory, the HPWS will help create higher levels of engagement by developing a relationship that employees will wish to sustain with the organization due to the perception of a fair relationship. In line with the empirical evidence provided above, we expect that this increased level of employee engagement leads to improved employee satisfaction and retention.

Consequently, the present study proposes that employee engagement is a mediator between HPWS practices (selection and recruitment, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation) and organizational performance (employee satisfaction and employee retention), leading to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a). Employee engagement (EE) mediates the effects of HPWS practices on employee satisfaction.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b). EE mediates the effects of HPWS practices on employee retention.

3.5. Employee Engagement as a Mediator between Servant Leadership and Organizational Performance

On the basis of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory, since a servant leader seeks to meet employee needs and provide a safe environment, their employees will exhibit higher levels of work engagement, leading to the success of the organization [

31,

79]. Servant leaders’ attention to employee needs and resource development can increase employee engagement [

82]. According to Van Dierendonck [

100], servant leadership is related to improving the employee outcomes, because the servant leaders invest the time to learn about their followers’ unique characteristics and help to develop them. Within the same scope, Carter et al [

14] and De Clercq et al [

17] highlight the positive role of servant leadership on engagement. According to Kell [

101], serving the employee selflessly is one of the most important characteristics of servant leaders that results in employees’ feeling safe, thus engaging them with organization [

79]. An additional supporting view is suggested by Wong et al. [

40] and Macey and Schneider [

102], who see leadership as one of the biggest factors that influences engagement in the workplace. Karatepe and Talebzadeh [

103] showed that SL played a vital role in enhancing employee engagement in an airline in Iran. De Clercq et al. [

17] indicated a significant impact of SL on EE in an information technology organization in Ukraine. Although there are some studies have shown that servant leadership can be a vital predictor of engagement in the service industry, empirical studies focusing on the relationship between servant leadership and employee engagement in the service sector are inadequate [

14]. Based on the discussion above we expect:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Servant leadership has a positive effect on employee engagement.

Studies have also revealed that servant leadership significantly influences individual performance levels, such as employee satisfaction and retention. In a study of university employees, Chain, Ding et al. [

104] found that servant leadership fostered satisfaction and employee loyalty. Hunter et al. [

38] also provided empirical results for the relationship between servant leadership and employee turnover intentions. Additionally, Wong et al. [

40] and Kaur [

105] showed that servant leadership is positively associated with retention.

We believe that the reason for this relationship between servant leadership and employee outcomes is higher levels of employee engagement. As discussed above, servant leaders create relationships that increase the engagement of employees, and it is this improved engagement that leads to the satisfaction and retention of employees.

However, no empirical research has measured the mediating role of employee engagement in the relationships of servant leadership with employee satisfaction and retention. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 7a (H7a). Employee engagement mediates the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction;

Hypothesis 7b (H7b). Employee engagement mediates the effects of servant leadership on employee retention.

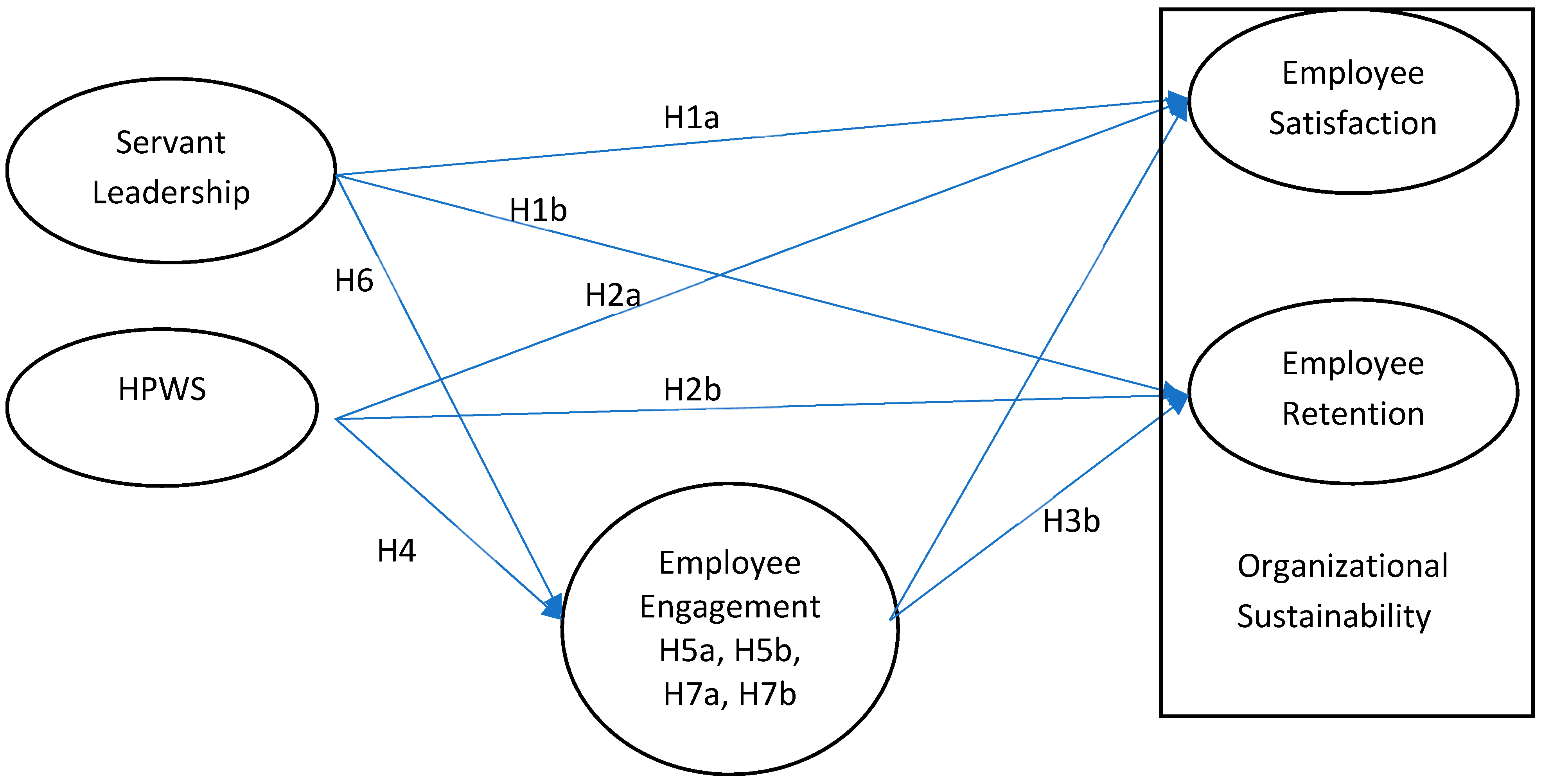

The conceptual model is shown in

Figure 1. The model suggests that HPWS practices are directly linked to employee engagement. In addition, the model shows that employee engagement enhance organizational performance. The researcher proposed that employee engagement the effect of HPWS practices and servant leadership on organizational performance.