Role of the Instructor’s Social Cues in Instructional Videos

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objective and Rationale

1.2. Research on Social Cues in Instructional Video

2. The Present Study

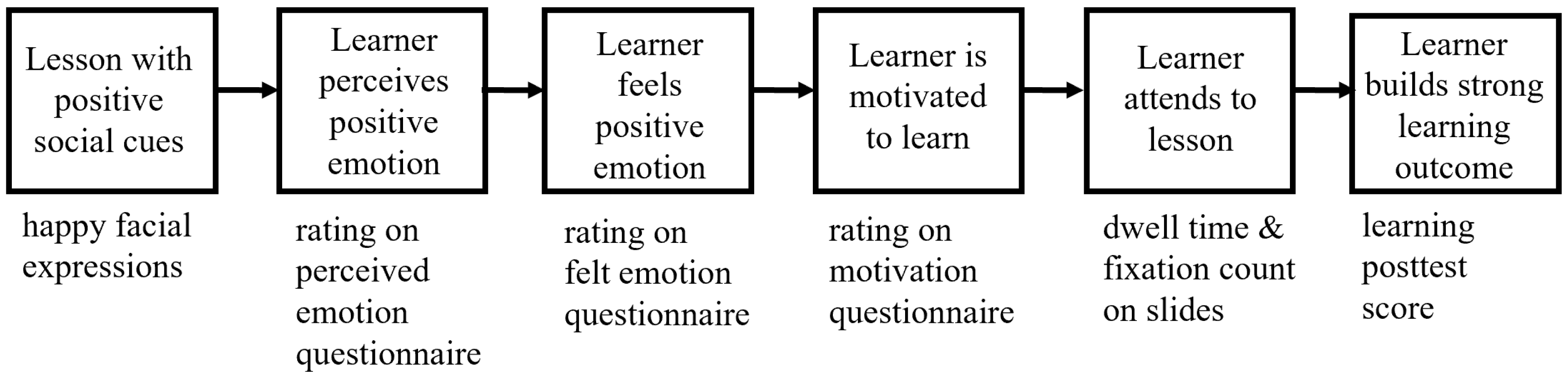

Theoretical Framework and Predictions

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Design

3.2. Materials

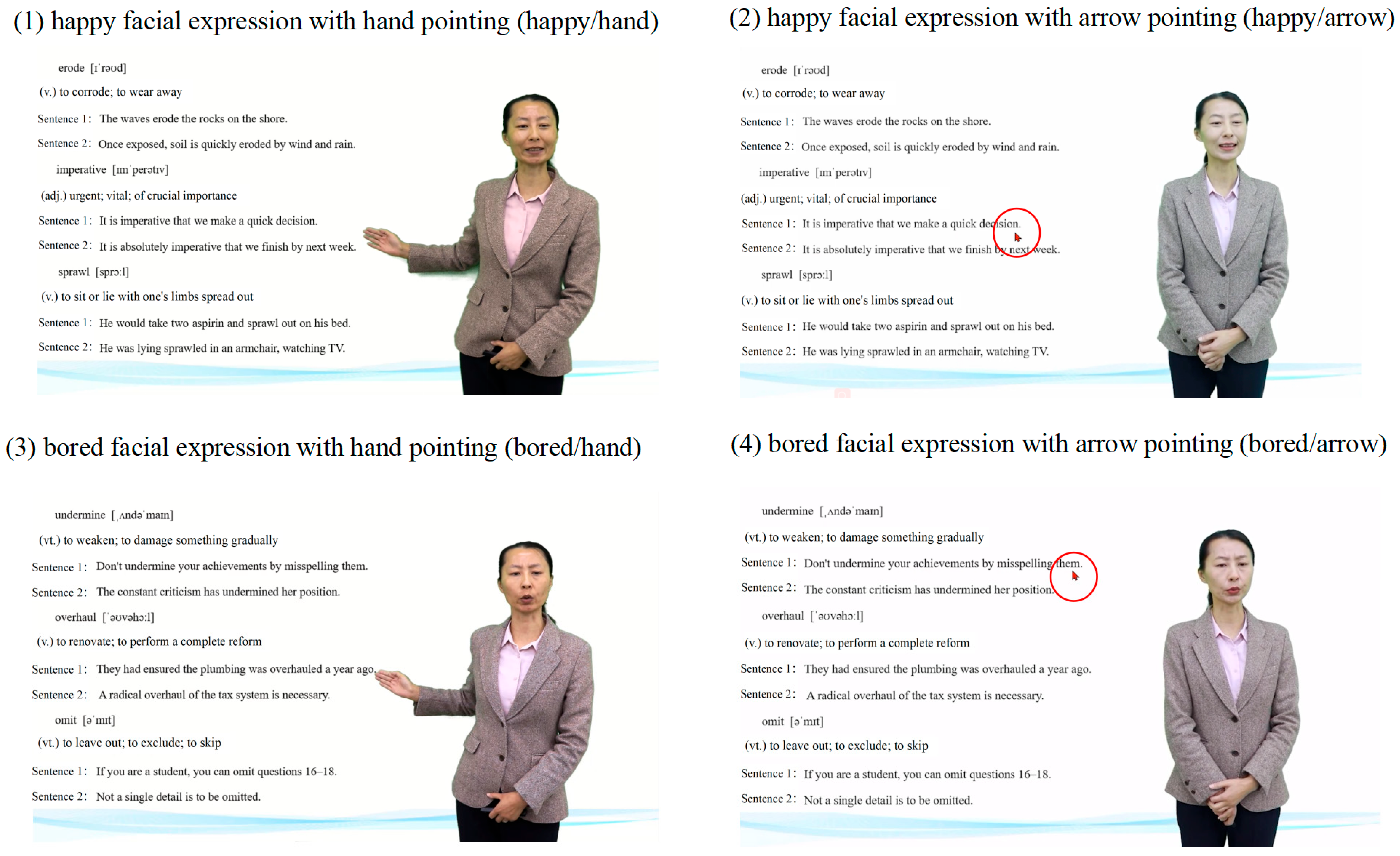

3.2.1. Video Lessons

3.2.2. Participant Questionnaire

3.2.3. Prior Knowledge Test

3.2.4. Perceived Emotion and Felt Emotion Questionnaires

3.2.5. Motivation Questionnaire

3.2.6. Learning Outcome Post-Tests

3.2.7. Eye Tracking Apparatus and Measures

3.2.8. Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Were Participants Equivalent Across Conditions?

4.2. Hypothesis 1: Perceived Emotion of the Instructor

4.3. Hypothesis 2: Felt Emotion

4.4. Hypothesis 3: Motivation to Learn

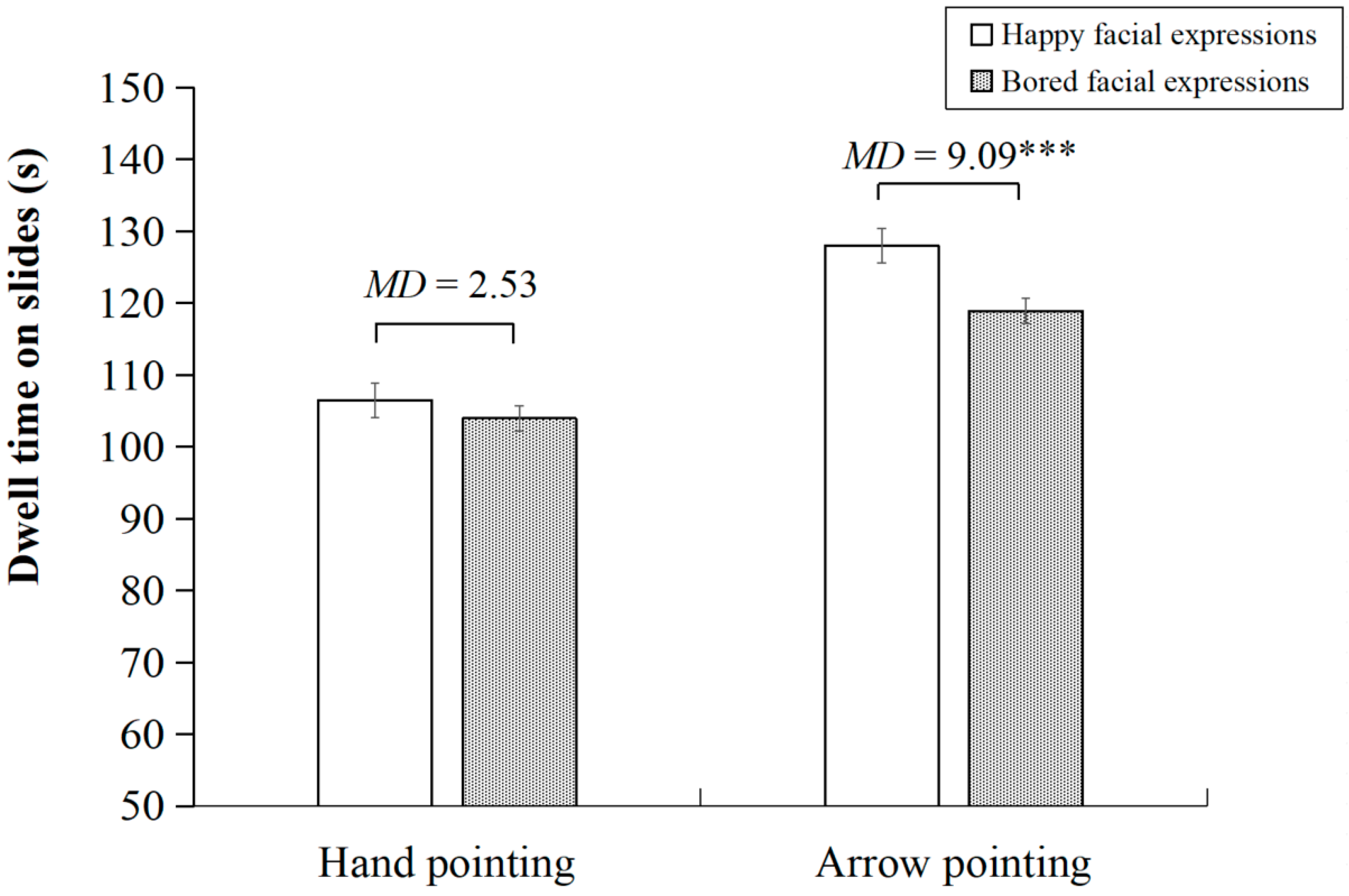

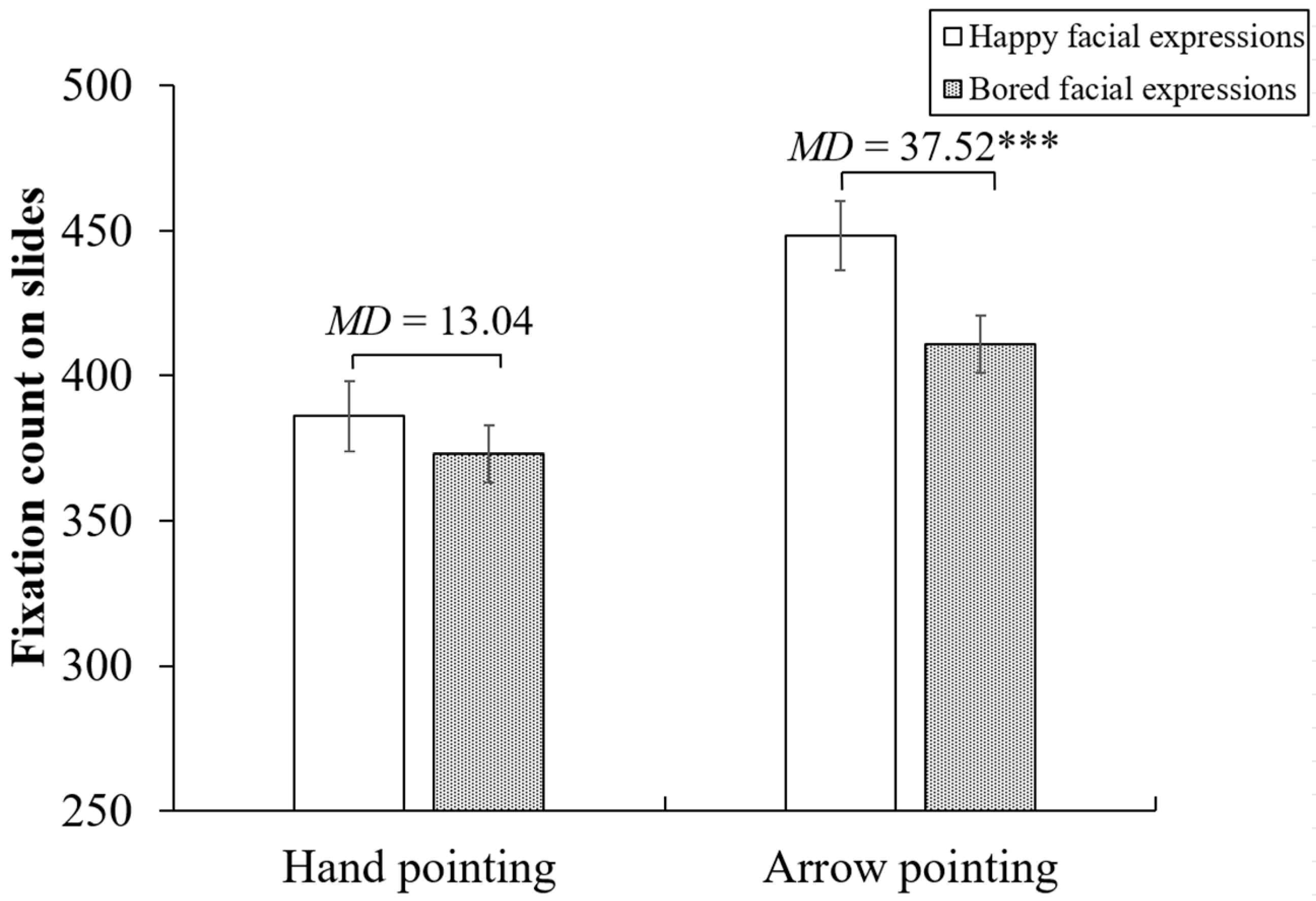

4.5. Hypothesis 4: Visual Attention to the Lesson

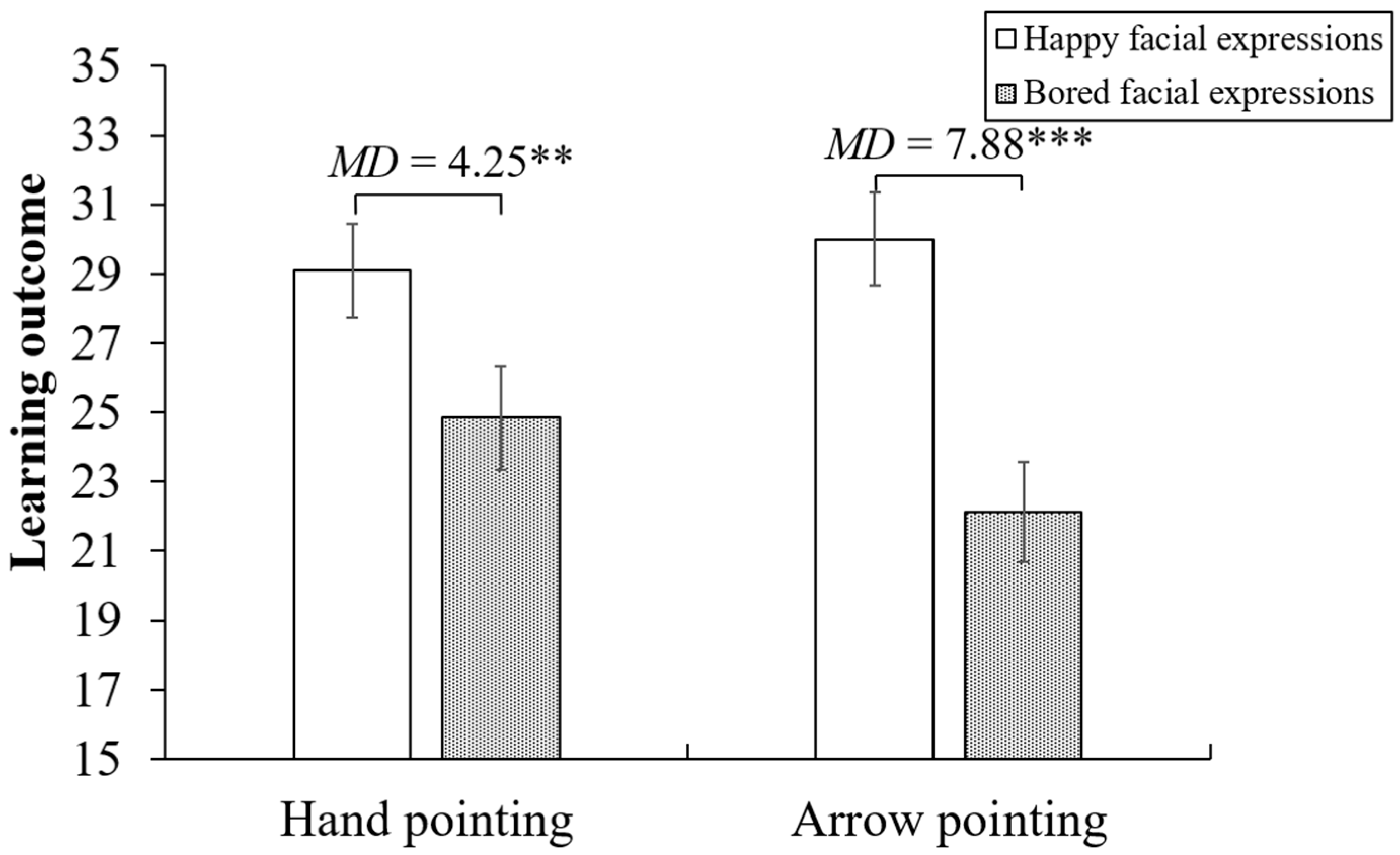

4.6. Hypothesis 5: Learning Outcome

5. Discussion

5.1. Empirical Contributions

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alemdag, E., & Cagiltay, K. (2018). A systematic review of eye tracking research on multimedia learning. Computers & Education, 125, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(1), 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H. M., & Saunders, J. A. (2023). The influence of valence and motivation dimensions of affective states on attentional breadth and the attentional blink. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 49(1), 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikha, H. B., Mguidich, H., Zoudji, B., & Khacharem, A. (2024). Uncovering the roles of complexity and expertise in memorizing tactical movements from videos with coach’s pointing gestures and guided gaze. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 19(5), 1883–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Dargue, N., Sweller, N., & Jones, M. P. (2019). When our hands help us understand: A meta-analysis into the effects of gesture on comprehension. Psychological Bulletin, 145(8), 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, B. B., Tabbers, H. K., Rikers, R. M. J. P., & Paas, F. (2007). Attention cueing as a means to enhance learning from an animation. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21(6), 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donges, U.-S., Kersting, A., & Suslow, T. (2012). Women’s greater ability to perceive happy facial emotion automatically: Gender differences in affective priming. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e41745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emhardt, S. N., Jarodzka, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., Drumm, C., Niehorster, D. C., & van Gog, T. (2022). What is my teacher talking about? Effects of displaying the teacher’s gaze and mouse cursor cues in video lectures on students’ learning. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 34(7), 846–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, L. (2022). The embodiment principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer, & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 286–295). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Mitchell, T., Simms, V., & Litchfield, D. (2018). Learning from where “eye” remotely look or point: Impact on number line estimation error in adults. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(7), 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horovitz, T., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning with human and virtual instructors who display happy or bored emotions in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, Q., He, Q., Luo, S., Huang, W., & Yang, Y. (2025). Does teacher enthusiasm facilitate students’ chemistry learning in video lectures regardless of students’ prior chemistry knowledge levels? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 41(1), e13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A. P., Mayer, R. E., Adamo-Villani, N., Benes, B., Lei, X., & Cheng, J. (2021a). Do learners recognize and relate to the emotions displayed by virtual instructors? International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 31(1), 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, A. P., Mayer, R. E., Adamo-Villani, N., Benes, B., Lei, X., & Cheng, J. (2021b). The positivity principle: Do positive instructors improve learning from video lectures? Educational Technology Research & Development, 69(6), 3101–3129. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Wang, F., & Mayer, R. E. (2023). How to guide learners’ processing of multimedia lessons with pedagogical agents. Learning and Instruction, 84, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margoni, F., Surian, L., & Baillargeon, R. (2024). The violation-of-expectation paradigm: A conceptual overview. Psychological Review, 131(3), 716–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marius, M., Iasmina, I., & Diana, M. C. (2025). The role of teachers’ emotional facial expressions on student perceptions and engagement for primary school students-an experimental investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1613073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2021). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, J., de Jong, B., van Montfort, D. P., Verdonschot, A., van Wermeskerken, M., & van Gog, T. (2023). Do social cues in instructional videos affect attention allocation, perceived cognitive load, and learning outcomes under different visual complexity conditions? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagne, B., Kessels, R. P. C., Frigerio, E., de Haan, E. H. F., & Perrett, D. I. (2005). Sex differences in the perception of affective facial expressions: Do men really lack emotional sensitivity? Cognitive Processing, 6, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z., Liu, R., Ling, H., Zhang, X., Wang, S., & Li, X. (2024). The emotional design of an instructor: Body gestures do not boost the effects of facial expressions in video lectures. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(3), 952–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Z., Liu, W., Ling, H., Zhang, X., & Li, X. (2023). Does an instructor’s facial expressions override their body gestures in video lectures? Computers & Education, 193, 104679. [Google Scholar]

- Plass, J., & Hovey, C. (2022). The emotional design principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer, & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 324–336). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, H. (2023). Instructors’ presence in instructional videos: A systematic review. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 8537–8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, H., Kayaduman, H., Taş, N., Battal, A., Kaban, A., & Bayram, E. (2025). Learning declarative and procedural knowledge through instructor-present videos: Learning effectiveness, mental effort, and visual attention allocation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 73, 3479–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Chen, Z., Wang, M., Chen, S., & Sun, J. (2024). Instructor’s low guided gaze duration improves learning performance for students with low prior knowledge in video lectures. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(3), 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, A. T., Fiorella, L., Gainer, M. J., & Mayer, R. E. (2018). Using transparent whiteboards to boost learning from online STEM lectures. Computers & Education, 120, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, A. T., Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). The case for embodied instruction: The instructor as a source of attentional and social cues in video lectures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(7), 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, H. Y., & Hung, K. E. (2025). Enhancing learner affective engagement: The impact of instructor emotional expressions and vocal charisma in asynchronous video-based online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 4033–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J., Van Merriënboer, J. J., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gog, T. (2014). The signaling (or cueing) principle in multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd revised ed., pp. 263–278). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., Chen, Z., Shi, Y., Wang, Z., & Xiang, C. (2022). Instructors’ expressive nonverbal behavior hinders learning when learners’ prior knowledge is low. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 810451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Feng, X., Guo, J., Gong, S., Wu, Y., & Wang, J. (2022). Benefits of affective pedagogical agents in multimedia instruction. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 797236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L., Liu, C., Li, Y., & Zhu, T. (2023). How to inspire users in virtual travel communities: The effect of activity novelty on users’ willingness to co-create. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. Y., Kang, S., & Kim, S. (2024). A non-verbal teaching behaviour analysis for improving pointing out gestures: The case of asynchronous video lecture analysis using deep learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(3), 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Wang, Z., Fang, Z., & Xiao, X. (2024). Guiding student learning in video lectures: Effects of instructors’ emotional expressions and visual cues. Computers & Education, 218, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Cheng, G., & Wu, L. (2023). Influence of instructor’s facial expressions in video lectures on motor learning in children with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 11867–11880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dependent Variable Measure | Experimental Condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happy/Hand (M ± SD) | Happy/Arrow (M ± SD) | Bored/Hand (M ± SD) | Bored/Arrow (M ± SD) | |

| Perceived emotion rating | 6.79 ± 1.32 | 6.79 ± 1.42 | 2.21 ± 1.10 | 2.52 ± 1.84 |

| Felt emotion rating | 5.61 ± 1.17 | 5.90 ± 1.05 | 4.68 ± 1.31 | 4.66 ± 1.29 |

| Motivation rating | 3.91 ± 1.12 | 4.20 ± 1.24 | 3.46 ± 1.28 | 3.34 ± 1.01 |

| Dwell time (s) | ||||

| Slides | 106.48 ± 13.53 | 127.99 ± 11.76 | 103.95 ± 9.69 | 118.90 ± 9.05 |

| Instructor | 5.56 ± 5.81 | 8.05 ± 9.78 | 5.24 ± 4.62 | 5.08 ± 6.31 |

| Fixation counts | ||||

| Slides | 386.11 ± 58.04 | 448.38 ± 68.78 | 373.07 ± 48.39 | 410.86 ± 56.63 |

| Instructor | 14.75 ± 13.72 | 18.21 ± 18.48 | 15.04 ± 14.12 | 13.52 ± 12.77 |

| Learning outcome score | 29.09 ± 6.76 | 30.00 ± 7.63 | 24.84 ± 8.42 | 22.12 ± 7.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pi, Z.; Huang, X.; Mayer, R.E.; Zhao, X.; Li, X. Role of the Instructor’s Social Cues in Instructional Videos. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010082

Pi Z, Huang X, Mayer RE, Zhao X, Li X. Role of the Instructor’s Social Cues in Instructional Videos. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010082

Chicago/Turabian StylePi, Zhongling, Xuemei Huang, Richard E. Mayer, Xin Zhao, and Xiying Li. 2026. "Role of the Instructor’s Social Cues in Instructional Videos" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010082

APA StylePi, Z., Huang, X., Mayer, R. E., Zhao, X., & Li, X. (2026). Role of the Instructor’s Social Cues in Instructional Videos. Education Sciences, 16(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010082