Abstract

The public debate on vaccines has been particularly relevant in Italy due to the introduction of childhood vaccination mandates and anti-COVID-19 vaccines. Our exploratory study focused on (1) identifying the media’s portrayals of childhood and adult vaccination, (2) highlighting the narratives used to portray individuals opposing vaccines and/or vaccine mandates, and (3) investigating the use of the term “No-Vax”. To these aims, we collected 2890 Facebook posts published by the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2023, via the (Meta) CrowdTangle application. Data were analyzed using quantitative and qualitative techniques. Results show the presence of four main vaccine-related narratives in the pre-pandemic period (2016–2019)—i.e., vaccination as threatened by fake news, as a lifesaving practice, as a political matter, as a subgroup requirement—and three narratives during the pandemic and post-pandemic period (2020–2023)—depicting vaccinations as a long-awaited achievement, as a social requirement, and as a tool in need of confirmation. The results further show that the term ‘No-Vax’ has some negative connotations and is unable to represent the diversity of vaccine-critical positions. The media’s role in shaping public opinion suggests a need for more nuanced reporting that acknowledges the diversity of views and concerns regarding vaccination. Future research should explore how different media outlets frame vaccine hesitancy and the impact of these narratives on public health communication.

1. Introduction

The debate around vaccination in Italy has become increasingly polarized over the past decade, reflecting broader tensions between public health, political authority, and media influence(s). This polarization intensified after the introduction of childhood vaccine mandates in 2017 and reached new heights during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to a global increase in measles cases in 2014–2015, several European countries have introduced or increased the number of mandatory vaccines for children, changing their immunization strategies and adopting different approaches to deal with non-compliance (Odone et al., 2021). Italy has been among the high-income countries that have adopted increasingly stringent childhood vaccination regulations (Attwell et al., 2021). Specifically, in June and August 2017, the Italian government implemented an expanded array of mandatory vaccines for children under 16 with Decree-Law No. 731 (the so-called “Lorenzin Decree”, named after the then-Minister of Health, Beatrice Lorenzin).2 Indeed, according to the 2014 Global Health Security Agenda, Italy was designated as a global leader in vaccination strategies,3 thus becoming the first European country to begin increasing the number of mandatory vaccines in 2017. Decree No. 73/2017, enacted into Law No. 119/2017, increased the number of required vaccines for children aged 0 to 16 from four to ten, introducing two main penalties for families that fail to comply: the payment of an economic fine and the exclusion of children who have not received or have received only some of their vaccinations from preschool services.4 The government’s measures and sanctions opened a public debate, polarizing public opinion and political actors (Casula & Toth, 2018).

The law encountered significant resistance from vaccine-hesitant families—vaccine hesitancy is “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services” (MacDonald et al., 2015, p. 4163)—and this early opposition laid the groundwork for how vaccination dissent would later be framed. These families have often been (negatively) labeled by the media and institutional communication as No-Vaxxers or anti-vaxxers (Capurro et al., 2018; Fattorini, 2023; Ward et al., 2019). However, this denomination does not account for the heterogeneity of vaccine-hesitant positions (Dubé et al., 2013), which do not necessarily imply vaccination refusal. Moreover, this label is generally reproduced by the media and institutions, fueling the idea that those people lack education—thus relying on a top-down deficit communication model (Goldenberg, 2016; Seethaler et al., 2019)—and are passive and uncritical recipients of information easily misguided by “fake news” (Bucchi et al., 2022).

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 significantly expanded the scope of public debates on vaccination, extending mandates to adults and further politicizing the issue. In the European landscape, Italy was also the first country to be impacted by COVID-19 (Indolfi & Spaccarotella, 2020) and the first to adopt a package of non-pharmaceutical interventions to mitigate the virus (Flaxman et al., 2020). In response to the health crisis, the Italian government, led by Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (in charge until January 2021), proclaimed the first national lockdown in March 2020, while in late April 2020, the containment strategy of the virus was intensified, extending further the non-pharmaceutical interventions. The anti-COVID-19 vaccination campaign started on 27 December 2020 (the so-called “Vaccine Day”) with the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine. The campaign was authorized and in agreement with the European Union in all European countries.5

The vaccine distribution in Italy started on 31 December 2020,6 and, concomitantly, the Italian government began implementing specific legislative measures to ensure high vaccination coverage. This approach was adopted and further supported by Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who was in charge between February 2021 and October 2022. In the spring of 2021, anti-COVID-19 vaccination became mandatory for all healthcare personnel in Italy (Law No. 76/2021),7 and three work-related sanctions—namely, demotion, salary suspension, and dismissal—were stipulated for those who did not meet the requirement. The government then established and implemented regulatory measures concerning the “Green Pass” or “Green Certification”. This certification could be obtained through vaccination, recovery from the virus, or a negative result of a molecular or antigenic test.8 Beginning in August 2021, the Green Pass was required to access several public activities, such as restaurants and public events, that would otherwise be inaccessible.9 These restrictions, along with the anti-COVID-19 vaccine requirements and the government’s overarching strategies for containing the virus, were strongly contested by thousands of Italian citizens who participated in the “No Green Pass” demonstrations (Alfano et al., 2023; Della Porta & Lavizzari, 2022). Before the advent of the pandemic, protests against childhood vaccination mandates were predominantly initiated by parents. However, in the subsequent pandemic context, these demonstrations also encompassed the adult population, who were also largely sustained by some political parties (Bertero & Seddone, 2021).

In November 2021,10 the mandate of the anti-COVID-19 vaccination was extended to personnel of schools, police forces, public rescue, and penal institutions. The sanction for non-compliance was suspension without salary until 15 June 2022. Moreover, in early 2022,11 the anti-COVID-19 vaccination mandate was extended to all people over 50 years of age and to academic personnel (independently from the age) with a non-compliance fine of EUR 100. Furthermore, the “Super Green Pass” was introduced as a requirement for all public and private workers until 15 June 2022, with penalties for non-compliance ranging from EUR 600 to 1500. This new certification could be obtained only by completing the vaccination cycle or recovering from COVID-19. The government officially ended the state of (health) emergency in Italy on 31 March 2022, and the mandatory COVID-19 vaccination—and the related sanctions for non-adherence—remained only for healthcare personnel until 1 November 2022.12 Children were also included in the government’s strategy to increase vaccination rates against COVID-19. Indeed, for those between 12 and 15 years of age, the vaccination campaign started in May 2021, while for those between 5 and 11 years of age, it started in mid-December 2021. Notwithstanding the absence of a mandatory requirement for anti-COVID-19 vaccines for children, the Green Pass was a prerequisite for access to public spaces (e.g., restaurants, libraries, gyms, and swimming pools) even for minors between 12 and 17 years of age.13 Furthermore, the Super Green Pass was required to use public transport for children over 12 years of age.14

As in the earlier case of childhood vaccine mandates, those who opposed the anti-COVID-19 vaccination policies were increasingly labeled as “No-Vaxxers”. During the COVID-19 pandemic, indeed, people who decided not to get vaccinated against COVID-19 or not to obtain the booster doses or who raised concerns were labeled as No-Vaxxers and faced different forms of stigmatization because they were transgressing “social expectations regarding contagion” (Wiley et al., 2021, p. 2). Fattorini and Balazka (2025) emphasize that a significant portion of the vaccine-compliant population might accept the anti-COVID-19 vaccine not out of genuine conviction, but because they felt pressured by institutional mandates, media, and prevailing social norms. This highlights how consent to vaccination can coexist with underlying ambivalence or even resistance—dynamics often obscured by the No-Vax label.

To understand how such labels became prominent in public discourse, it is essential to examine the media’s role in shaping public perceptions of vaccines and vaccine resistance. Media communication has been identified as a contributing factor to the development of vaccine-hesitant attitudes in terms of childhood and adult vaccination and in the construction and amplification of the public perception of a particular risk (Capurro et al., 2018; Kahan, 2014; Kasperson et al., 1988). According to framing theories, health-related issues—such as childhood vaccination and the COVID-19 pandemic—“are ‘framed’ to provide specific meanings, situational insights and applicable cues with the purpose of raising health awareness” (Coleman et al., 2011; Yousaf et al., 2022, p. 1856).

Framing not only informs but also guides public interpretation of events and social behavior, making it a critical tool in shaping attitudes toward vaccine compliance and dissent. Framing is often linked to agenda-setting, and media can thus orient citizens’ opinions toward and awareness of specific topics by accentuating specific attributes and/or issues (Kim & Willis, 2007). As highlighted in the research conducted on media coverage of the flu crisis in the United States by Pan and Meng (2016), different media frames of the issue were adopted at different stages of the crisis to inform people.

In this framework, the media constitutes an ever-present resource for health awareness and a potential determinant of public opinion (Bullock & Shulman, 2021). Indeed, the media can contribute to defining the issues of vaccines and vaccination through the adoption of specific framing narratives (Wagner et al., 2024). When looking at the public debate surrounding the vaccine issue in the United States, Brunson and Sobo (2017) highlight that narrative framings of vaccination are characterized by high polarization—i.e., pro- versus anti-vaccines narratives. Court et al. (2021) analyzed the media discourse about childhood vaccination policies between 2008 and 2018 in Australia, focusing specifically on the “anti-vaxxer” label and framing. The term entered the media narrative when vaccination policy changes were discussed, also bringing under the same label parents who decided not to vaccinate their children, along with people actively advocating against vaccines. Furthermore, the authors identified six main media narratives portraying parents as deviating from the social norms and thus deserving punishments; uninformed and requiring education; at the mercy of anti-vaccine movements (and therefore in need of protection); informed and to be respected; selfish and privileged; or facing barriers to vaccination, rather than being disinclined. Similar judgmental narratives and negative perceptions of vaccination skepticism have been found by Rozbroj et al. (2019). According to framing theory, not only the news selection and the frequency of its publication on media outlets but also the saliency and visibility given by the media coverage can influence people’s attitudes “by enhancing the accessibility of the beliefs” (Bullock & Shulman, 2021; Entman, 1993; Guenther et al., 2020; Yousaf et al., 2022, p. 1856).

Media frames do not just inform but shape what the public perceives as legitimate positions in the vaccine debate. In their research on vaccination-related mainstream media discourses in seven European countries (including Italy) between 2019 and 2021, Wagner et al. (2024) showed that the different levels of visibility of vaccine-critical positions constituted the main difference between the pre-pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic period. Until early March 2020, indeed, those positions were generally less often reported by the media. Focusing on the vaccination narratives, in all countries considered, vaccines were portrayed as being a societal achievement, a tool to control and fight old diseases, a preventive measure for all of society, and the target of anti-vaccination movements and fake news attacks. After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine portrayals were specifically linked to the broader pandemic context and the political, health–scientific, and economic spheres involved. Mainstream media also framed vaccination as a tool to ensure the community’s safety and solidarity, a scientific achievement necessary for a secure future, and a preventive measure embedding economic interests. These narratives also discussed the role that national governments should have played in managing the anti-COVID-19 vaccines.

In this increasingly complex and polarized context, the Italian media landscape followed similar patterns, marked by politicization and polarization. The public debate on childhood and anti-COVID-19 vaccines has been particularly relevant in Italy. Starting in 2017, the public debate on vaccination has been characterized by a particularly pronounced politicization, polarization—between those in favor of vaccines and those against—and spectacularization of the issue (Casula & Toth, 2018; Lovari et al., 2021). The polarization of the Italian media landscape has been further accentuated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the relationship between science and politics became more explicit (Loner et al., 2023). As Bucchi (2000) highlighted, the discourse surrounding vaccinations is frequently influenced by political factors rather than being solely grounded in scientific evidence because of media communication strategies. Other authors (Leach & Fairhead, 2007, p. 2) noted that despite the common portrayal of vaccines as a neutral and undisputable public good, they are intertwined with politics, “with struggles over status, authority, and value”.

Despite the centrality of media narratives in shaping vaccination discourse, few studies have specifically examined how Italian media portray vaccination and dissenters across both the childhood mandate and COVID-19 periods. Odone et al. (2018) analyzed the vaccine-related news coverage in the Corriere della Sera newspaper (among the major Italian news brands) between 2007 and 2017. Results showed an increase of 150% of the articles mentioning the vaccine issue after introducing the law on mandatory childhood vaccination in July 2017, highlighting the issue’s high societal and political relevance in the public debate. Interestingly, overall, the percentage of news with a positive or neutral approach to vaccination decreased from 97% in the second half of 2016 to 79% in the second half of 2017, with an increase over time of a hesitant or critical approach—not necessarily reflecting a general criticism towards vaccines but instead a broader criticism toward “the legitimacy and usefulness of making immunization mandatory” (Odone et al., 2018, p. 2534). In their analysis of scientists’ and experts’ positions on mandatory childhood vaccination in several Italian media outlets between March 2017 and November 2018, Gobo and Sena (2022) also included the scientific community’s critical views that appeared in the public debate. The authors identified nine different positions towards immunization—from full support of mandatory and recommended vaccines to outright refusal of all vaccines. This highlighted, on the one hand, the presence of different levels of vaccine-related criticism among scientists and experts who intervened in the public debate; on the other hand, the need to consider the conflict is not primarily between those who support or oppose vaccination. Rather, the contrast between these scientifically based perspectives and positions lies in “distinct and sometimes opposite or non-negotiable motivations and definitions of disease and freedom, patient, community, and individual empowerment” (Gobo & Sena, 2022, p. 35). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, Caroselli and Schiano (2023) looked at the frequency of appearance of the “No-Vax” term in La Repubblica’s articles (one of the major news brands in Italy) and the narrative linked to this label during 2021. They noticed that the No-Vax-related issue was prevalent in the considered newspaper communication of the pandemic, even though the percentage of non-vaccinated people was considerably low compared to those who received the vaccine, thus amplifying the collective attention on the issue and often portraying the No-Vaxxers as the “folk devils” (Cohen, 1972).

The role of media communication as a source of knowledge and its potential to influence audiences’ attitudes and beliefs (Guenther et al., 2020) underscores the necessity to examine the framing of health-related issues, such as vaccines and vaccination policies. For instance, in the case of vaccination, media narratives can contribute to shaping the risk perception and supporting the effectiveness of vaccination campaigns. Despite the growing body of research on health communication and framing, no prior study has systematically analyzed Italian mainstream media’s vaccine narratives considering both childhood and adult vaccination and including two major vaccine-related events (i.e., childhood vaccination mandates and the COVID-19 pandemic). This exploratory study analyzes news posts published by the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) regarding the vaccine issue between 2016 and 2023. Specifically, our analysis adopts a quantitative and qualitative approach to address three main research questions (RQ): (1) How does the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) frame the vaccine issue? (2) What specific narratives are used to portray individuals opposing vaccines and/or vaccine mandates? (3) How is the term “No-Vax” employed in these narratives, and what implications does this have for public discourse?

2. Materials and Methods

The data for this research consists of 2890 posts published on Facebook by the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2023. ANSA is the leading news agency in Italy, which also provides news to citizens online. According to the Digital News Report 2024 by Reuters Institute, among the major Italian news brands, ANSA is the most trusted (75%) by citizens (Newman et al., 2024). Furthermore, with 1.9 million followers, its Facebook page is particularly popular.

ANSA’s Facebook posts were downloaded through the CrowdTangle platform (Meta) using the following (Italian) keywords related to vaccines and vaccine skepticism: “vaccin*”, “vax*”, “novax”, “novacc*”, “antivacc*”, “antivax”, “no vax”, “no-vax”—where “*” indicates all the possible endings of the keyword (CrowdTangle Team, 2023). The “No-Vax” term is generally the most used in Italian to indicate all those people skeptical about vaccines and/or vaccination policies.

The timeframe considered for our analysis includes two main sub-periods: the first, from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2019; the second, from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023. Before the pandemic (2016–2019), vaccine-related news focused primarily on childhood vaccination mandates and the sanctions introduced in 2017. The subsequent period (2019–2023) was characterized by the onset and worldwide spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, including the development and rollout of vaccines, the imposition of vaccination mandates for specific occupational categories and age groups, and the application of mRNA vaccine technology to other diseases.

ANSA’s posts consist of a brief news item summary and a link to the press agency’s website page with the full article, thus providing a quick and easy way to access information. The collected posts, originally in Italian, were then translated into English.

A total of 324 posts were published before 2020, i.e., before the outbreak of the pandemic, while the majority, 2566 posts, were published during the COVID-19 emergency (Table 1). The selected posts largely concern vaccinations in general (2803), and only a small part (87) concern No-Vax positions.

Table 1.

ANSA: Facebook posts selected by year and topic (2016–2023, N = 2890).

We applied a mixed-methods approach (Creswell, 1999) to analyze the data, combining quantitative and qualitative techniques in a complementary and sequential manner. This design allowed us to explore our three research questions in an integrated way. In the first phase of the analysis, we used quantitative methods to provide a broad overview of the discursive landscape in ANSA’s coverage of the vaccine issue (RQ1). Specifically, we applied the following: (a) a frequency analysis of the most common words in the posts, (b) a word community detection analysis (Bedi & Sharma, 2016), and (c) a sentiment analysis (Liu, 2012) using FEEL-IT, a Python package (stable v1.0.2) tailored for sentiment classification in Italian (Bianchi et al., 2021) that automatically determines a text’s sentiments or positive/negative opinions (Taboada, 2016).

Word community detection, conducted with the Leiden algorithm (Traag et al., 2019)15, enabled us to map clusters of co-occurring terms and identify recurring themes and discursive patterns. This helped to detect narrative structures and specific framings of both the vaccine issue in general (RQ1) and vaccine skepticism (RQ2). These communities were visualized using the R package igraph (Csárdi et al., 2024), facilitating the identification of semantic relationships between terms, such as how “No-Vax” is situated within larger narrative frameworks (RQ3). The sentiment analysis complemented this by revealing the emotional tones associated with key narrative clusters.

The second part involved a qualitative, interpretive analysis of the selected posts. This stage was crucial for deepening and validating the insights gained from the quantitative analysis (Williamson et al., 2018). With the qualitative inquiry, we analyzed in detail ANSA’s framings of the vaccination issue in the two considered periods—i.e., 2016–2019 and 2020–2023—(RQ1), unpacked how individuals opposing vaccines and mandates were portrayed (RQ2), and critically examined the discursive use and implications of the term “No-Vax” (RQ3). This qualitative dimension enabled us to contextualize the findings and understand the nuances behind the dominant narratives detected in the first phase.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the analysis of the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) posts published on Facebook before, during, and after the pandemic outbreak. The first subsection compares the posts published between 2016 and 2019 with those published between 2020 and 2023. The subsequent subsection focuses on analyzing posts related to news referring to No-Vax positions.

3.1. Pre-Pandemic Vaccine-Related Communication

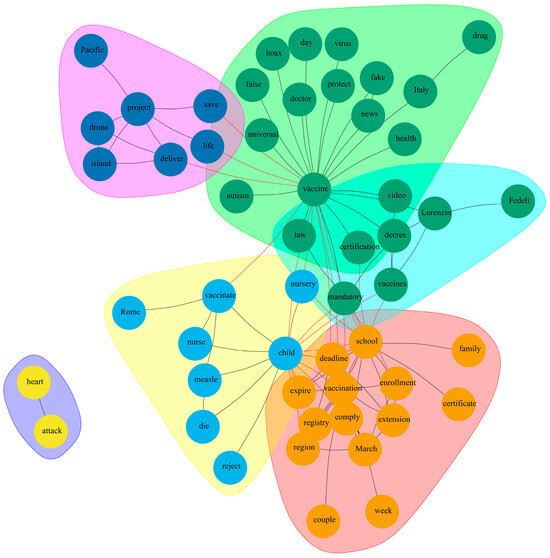

Between 2016 and 2019, most of ANSA’s communication about vaccines focused on a few narratives related to specific themes. The community detection analysis makes it possible to represent these themes as a network of words, in which the words that tend to co-occur are connected to form clusters or communities that identify as many narratives.16 The result is represented in Figure 1, from which four main vaccination narratives emerge: (1) vaccination as threatened by fake news; (2) vaccination as a lifesaving practice; (3) vaccination as a political matter; (4) and vaccination as a subgroup requirement.

Figure 1.

The network of narratives pre-COVID-19 in ANSA’s posts: 1 January 2016–31 December 2019 (n = 324).

Other smaller groups of words identify minor narratives related to new scientific and technological discoveries in the vaccination field. For instance, one of these groups contains news about the possibility of developing a vaccine to prevent other pathologies, such as heart attacks (Figure 1, bottom-left), and another contains news about the first experiments using life-saving postman drones to deliver medicines and vaccines (Figure 1, top-left).

3.1.1. Vaccination as Threatened by Fake News: Debunking Vaccine-Related False Information

The first narrative includes posts about fake news and the side effects of vaccines and is identified by the presence of words such as “fake”, “news”, “hoax”, “false”, and “autism” (Figure 1, top-center). Some post fragments summarize this cluster of words well. The first is extracted from a post published on 21 February 2018 and informs about the anniversary of the first fake news regarding the relationship between autism and vaccines:

The study that spread the hoax about the link between autism and vaccines is 20 years old. It was published in Lancet in 1998 and then withdrawn, but loved by anti-vax.

ANSA often adopts a top-down communication that aims to assume an “educational” role for the population against fake news, proposing fact-checking, as in a post from 30 December 2019:

Fake news and health, from tumours to vaccines: the most viral of 2019 #fakenews #ANSA

Other times, ANSA directly links to information published by organizations and research institutes whose authority is unquestionable, as in this fragment from 16 July 2017, in which it directly refers to a report developed by the Italian National Institute of Health (Iss):

Health, how to defend yourself from fake news about #vaccines, handbook #Iss.

3.1.2. Vaccination as a Lifesaving Practice: Childhood Vaccination Information and Promotion

The second narrative concerns information on childhood vaccination, with special attention to diseases for which coverage was low. Many posts focus on vaccination uptake rates against measles, a disease that can also lead to serious consequences for adults and pregnant women. The theme is identifiable by words that include “measle”, “child”, “die”, and “reject” (Figure 1, bottom left).

From the posts, it can be noted that ANSA tries to promote awareness of the risks faced by the unvaccinated population. For example, in a message published on 11 November 2016, an international report is cited in which the number of deaths among unvaccinated children is compared with that of children who were saved thanks to vaccines:

Measles: 400 children die per day, but 20 million are saved with vaccines.

In some messages, concerns about the low coverage rate of children against this disease are voiced, citing international organizations. An example is a news item from 25 April 2019, which reports the alarm raised by the humanitarian international organization UNICEF:

#Unicef alarm, 110 thousand cases of #measles in the world in the first 3 months of 2019. Italy is fifth for children not vaccinated against measles.

Finally, sometimes ANSA reports the news of the death of children who were not vaccinated because of their parents’ choice or because of their medical condition. An example is a post from 23 June 2017, about a child with leukemia—and therefore immunosuppressed—who died after contracting measles:

#Vaccines Child dies from #measles.

The post links to the article published on the ANSA website, in which the head physician of the hospital where the child was hospitalized emphasized in an interview the need for increased vaccination coverage against this disease because “if this has happened, it means that there must be a reminder to everyone to reiterate that we must get vaccinated: to protect our children, but also out of a sense of responsibility towards others, the weakest, who may not be able to do it”.

3.1.3. Vaccination as a Political Matter: Childhood Vaccination Mandates and the Political Forces

The third narrative concerns the public debate around the law promoted by the Minister of Health, Beatrice Lorenzin, in 2017. She held this institutional position until 2018, when the center-left leaders presided over the government (i.e., Letta, Renzi, and Gentiloni). The decree initially made twelve vaccines mandatory (then its legislative translation into law decreased the number of mandatory vaccines to ten) for children up to 16 years of age and introduced economic fines and exclusion from preschool services (i.e., nursery schools and kindergartens) for those who do not adhere to the national vaccination schedule. Thus, this narrative is identifiable by a few words, including “decree”, “certification”, “law”, “mandatory”, “Lorenzin” (Minister of Health), and “Fedeli” (Minister of Education) (Figure 1, center, to the right).

The news provided by ANSA followed both the progress and implications of the law and the debate and protests of those who opposed mandatory vaccination. The post of 1 June 2017 shows one of the demonstrations that were organized during that period:

#Vaccines, paper bombs, pamphlets with syringes, and zombies against #Lorenzin.

The demonstrations of the so-called No-Vaxxers are widely documented by ANSA, which also gives voice to the Minister of Health’s responses, as in this fragment from 9 February 2018:

#Lorenzin: behind the #novax there is a huge business #vaccines

Politicians also participated in the debate. Among the most skeptical towards mandatory vaccination are some members of Italian populist parties, including the radical right League with its leader (Salvini), as results from this post from 10 January 2018:

#Salvini: “When we govern, we will remove the obligation on #vaccines”.

The skepticism and the affirmation that the mandate should be changed also involved some members of the Five Star Movement (M5S). As an example, in a post from 8 June 2017, ANSA reported the news of an attack from an M5S member of parliament against the Minister of Health, who accused her of having received money to promote the law:

Sibilia #M5s: ‘Vaccine? It is mandatory for # Lorenzin’s madness. Who knows how many Rolexes she received for the decree?’. The minister sues him.

3.1.4. Vaccination as a Subgroup Requirement: Childhood Vaccination Mandates Implementation Issues

The fourth narrative is still linked to the vaccination mandates, but in this case, the communication focuses on the deadline set to fulfill the vaccination requirements in March 2018. Vaccination is a prerequisite for enrolment in preschool services for children between 0 and 6 years old. Many voices asked to postpone the application of this law. This request was mainly because the mandate would have excluded non-compliant children already attending preschool services before the end of the school year and prevented non-compliant families from enrolling their children. In the network of word communities, these posts are identifiable by the words “school”, “enrollment”, “family”, “certificate”, “deadline”, “expiry”, “comply”, “March”, and “extension” (Figure 1, center, bottom).

Concordantly, the news related to this narrative focused mainly on the deadline, the implementation timing, and the possibility of obtaining extensions, resulting in conflicting reports. This generated information chaos that required several interventions by the Minister of Health to clarify the issue. A post from 10 February 2018 exemplifies Lorenzin’s position of not allowing for any postponement on the matter:

#Vaccines, Lorenzin: ‘No extension. Fines will be issued after March 10’.

ANSA also reported the difficulties of health institutions in dealing with the (suddenly) increased demand for vaccinations from an organizational point of view, as can be seen in the post from 1 January 2018:

#Vaccines, the expert says: Vaccination centers are in chaos, overcrowded, and understaffed, given the March 10 deadline.

3.2. Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Vaccine-Related Communication

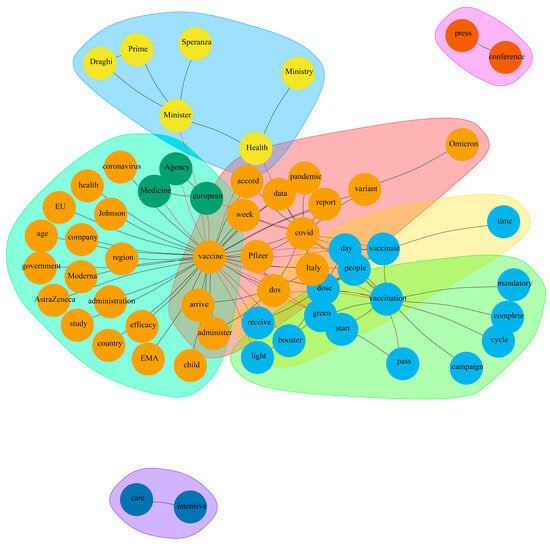

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of posts has multiplied, and the narrative’s focus has shifted to the demand to satisfy the population’s need for constant, up-to-date news. The need to deal with the emergency and the uncertainty has brought to the forefront the urgency to protect oneself from the virus. Furthermore, different from what happened in the case of childhood mandatory vaccination, in this case, the COVID-19 crisis had a global impact, and the vaccine-related issue interested the entire population regardless of age group. Therefore, the number of posts increased with the spread of the pandemic and resulted in a helpful source of information about the most recent news provided by scientists and health and political authorities dealing with the situation. From the analysis of the communities of words, it is possible to identify three vaccine-related narratives—mainly referring to anti-COVID-19 vaccines—that emerged from the news posted between 2020 and 2023 (Figure 2): (1) vaccination as a long-awaited achievement; (2) vaccination as a social requirement; (3) vaccination as a tool in need of confirmation.

Figure 2.

The network of post-COVID-19 narratives in ANSA’s posts: 1 January 2020–31 December 2023 (n = 2566).

In addition, other minor networks concerning the national and international actors managing the pandemic from a health and political point of view emerged: the intensive care units of hospitals (Figure 2, bottom left), the government and the Health Ministers in office in the four years analyzed (top-center), the European Medicines Agency (center), and the press conferences of Giuseppe Conte—President of the Council during the first stages of the pandemic—as well as representatives of international health organizations (top-right).

3.2.1. Vaccination as a Long-Awaited Achievement: The Availability and Efficacy of the Anti-COVID-19 Vaccine

The first narrative includes the posts with the news announcing the arrival and discovery of COVID-19 vaccines. This type of information was the most anticipated news during the first year of the pandemic, as Italians were particularly concerned by the negative consequences of the virus, given the substantial surge in infection and mortality rates, particularly in the country’s northern regions. This topic is identifiable by words containing the names of major pharmaceutical companies “Johnson & Johnson”, “AstraZeneca”, and “Moderna,” which have produced anti-COVID-19 vaccines—generally, the names of these companies were used to refer to their vaccines (respectively, Janssen, Vaxzevria, and Spikevax). Additionally, other terms refer to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), which is responsible for the evaluation and approval of pharmaceutical products in the European Union, and finally, aspects regarding the arrival, management, and efficacy of the vaccine (e.g., “arrive” and “efficacy”) (Figure 2 center-left).

Some posts announce the arrival of vaccines or vaccine-related agreements with pharmaceutical companies for the delivery of new doses, as in this fragment from 13 June 2020:

#Speranza [Minister of Health from 2019 to 2022]: Signed the agreement for #Oxford #vaccine doses. ‘400 million units from #Astrazeneca for Europe by the end of the year.’

Many of ANSA’s messages in this narrative aimed to reassure the population about vaccines’ effectiveness. An example is a post from 9 November 2020, in which the American immunologist Anthony Fauci is cited:

#Covid, #Fauci, ‘the efficacy of the #Pfizer #vaccine is extraordinary’.

Other news reports directly reported announcements by pharmaceutical companies that provided data on the efficacy of the anti-COVID-19 vaccine they developed. An example is this post from 30 November 2020:

According to the results of phase 3 tests on 196 cases, the American company Moderna vaccine has demonstrated an efficacy of 94.1% against COVID-19 and 100% in the most severe cases.

3.2.2. Vaccination as a Social Requirement: The Management of the COVID-19 Vaccination Campaign and the Green Pass

The second narrative focuses on disseminating information to support vaccination campaigns and provide updates on their progress. In addition to its informative function, this narrative reinforces the government’s efforts to encourage the population to receive immunizations. Furthermore, it contributed to providing news on the debate around the Green Pass and, at a later stage, on managing the post-pandemic phase. The words that identify this narrative are, among others, “campaign”, “vaccination”, “green pass”, “booster”, “vaccinate”, “day”, “cycle”, and “receive” (Figure 2, bottom-right).

An example of how ANSA has informed the citizens of the progress of the vaccination campaign and supported the institutional vaccination strategy is a fragment from a post from 26 July 2022. This post, like many similar ones, communicates confidence and serves a motivational function. The message quotes the Minister of Health’s words:

The vaccination campaign has been a success in our country. Over 90% of people over 12 have completed the first cycle. We have carried out almost 40 million boosters, placing us among the best results in Europe and the world.

This narrative also includes the debate around the ostensibly mandatory nature of the Green Pass and then the Super Green Pass, especially because of its link to the possibility of working for specific professional groups. In this case, the messages convey information regarding governmental measures adopted and report protests against these measures, including demonstrations that have seen clashes between protesters and police forces. An example of an informative post is a fragment from 2 February 2022, which announces the measures and restrictions of the government regarding mobility, schools, and some economic activity restrictions based on vaccination status:

There are no more restrictions for the vaccinated, even in the red zone18; green pass with unlimited duration for those who have completed the vaccination cycle but also for those who have only had two doses and have recovered from Covid, quarantine at school from 10 to 5 days and only for the unvaccinated, distance learning that starts from five cases or more for nurseries, kindergartens and elementary schools, foreigners who will be able to access hotels and restaurants even if they only have the basic pass. These are the new anti-COVID rules decided today by the government. #ANSA.

In other ANSA posts, the topic shifts to the No-Vax and No-Green-Pass protests. Those people were manifesting against the Green Pass certification and the broader measures regarded as encroachments on personal freedom. An example is a message from 11 September 2021:

The “no vax” and no Green Pass people rallied throughout Italy. In Piazza del Popolo, in Rome, there are also thirty members of Forza Nuova [a far-right political movement]. In Turin, there is tension between demonstrators and the police.

3.2.3. Vaccination as a Tool in Need of Confirmation: The Evolution of the Pandemic and the Efficacy of Anti-COVID-19 Vaccines Against Virus Variants

The third narrative focuses on news that informs the population about the contagion and the virus’s variants. It contains news reports and data on the infections, new variants, and, above all, the effectiveness of vaccines against these variants. The theme is identified by words such as “covid”, “variant”, “Omicron”, “report”, and “data” (Figure 2, in the center, towards the right).

News about the contagion often invites the population to respect the measures adopted by the government in light of the constantly changing virus. An example is a post from 9 July 2021 that summarizes the weekly report of the Ministry of Health and also talks about the “Delta” variant of the virus:

Delta variant circulation is on the rise in Italy, and in addition to following up on cases and completing vaccination cycles, necessary measures must be followed to prevent increased viral circulation.

As for the news on the SARS-CoV-2 variants, two types of messages are observed. The first is news that conveys fear about the potentially harmful effects of the infection. These messages increase the virus-related risk perception and invite the population to follow the institutional dispositions, as in this post from 29 November 2021:

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that the Omicron variant of the coronavirus could have “serious consequences”.

The second type of message comprises posts that convey a more reassuring message, citing authoritative voices who affirm that vaccines are also effective against variants. An example is this fragment from a 21 September 2023 post:

The vaccines approved by the EU also protect against the Covid Eris variant. This was stated by the director of the EMA (European Medicines Agency).

3.3. Framing Vaccination Skepticism

Only 87 posts mentioned No-Vaxxers (and the various declinations of the term, such as “anti-vaxxers”) and related topics. A total of 13 out of 87 posts were published before 2020, while 74 were published after the pandemic outbreak. Even if the number of posts mentioning the No-Vax term is limited compared to that about vaccination, the analysis of these 87 posts is still useful as it shows how Italian mainstream information sources address and communicate vaccination skepticism.19

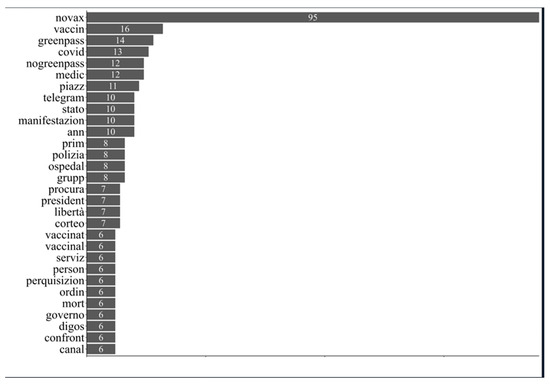

The analysis of the words most frequently used when mentioning No-Vaxxers (Figure 3) shows that the narrative surrounding this topic focuses on vaccines, the Green Pass, doctors (“medic”), street protests (“manifestazion”, “piazz”, and “corteo”), and the police forces (“polizia” and “digos”). Interestingly, the posts mention the platform for instant messaging Telegram (“canal” and “telegram”), often used by organized vaccine-skeptical groups to organize their activities and advocate for their positions through dedicated channels.

Figure 3.

Most used words in the ANSA’s posts mentioning the term “No-Vax” (n = 87).

The ANSA’s posts frequently report demonstrations as these groups often organize protests against the vaccination policies and the measures to contain the pandemic—especially the Green Pass—as in this post from 13 November 2021:

Saturday of alert for the protests. In Milan, the seventeenth no Green Pass demonstration is expected, and an initiative by the no vax guru Robert F. Kennedy Jr., son of Bob. In Rome, a no-Green Pass demonstration is expected at the Circus Maximus, with 1500 people expected. #ANSA.

Some of the news also mentions Telegram. This platform is a channel for non-mainstream information and connections. However, it is also used to coordinate protest actions, which can include appeals to take action against the law, as in this message from 7 February 2022:

An appeal to “set fire to the Turin Prosecutor’s Office” was launched on Telegram in the No Vax area chats. The message is now being examined by the Digos [a political intelligence branch of the Italian police force].

ANSA’s news also reports that Telegram (and other social media platforms) is used to spread fake news, as in this fragment from a post on 21 December 2021:

With the pandemic, the phenomenon of online fake news has exploded. In the last five months, more and more people on Telegram have followed no-vax channels or groups (+480%). There are 49 channels or groups against the Green Pass, and almost one in two (45%) is involved in selling fake certificates. Potentially fake content related to COVID-19 vaccines that concern the danger of adverse effects is growing sharply (+49%) and represents over 73% of the total.

Doctors and healthcare workers also play an important role in this narrative. Doctors are sometimes mentioned as victims of threats by anti-vaccination groups. Other posts relaunched the healthcare professionals’ appeals to get vaccinated against COVID-19, as in this message from 5 December 2021:

In Milan, a healthcare worker faces the no vax square despite death threats. ‘I experienced the pandemic on ambulances in places like Bergamo, Como and Milan. I am convinced that most could change their minds if they were well informed. I will convince them to get vaccinated one by one.

Furthermore, other posts also refer to doctors and nurses No-Vaxxers, such as this post from 31 December 2021:

He pretended to vaccinate no-vax people; a physician was arrested in Tuscany. The man received no vax patients in his clinic, certifying that they had been vaccinated against Covid even though he had not done so.

An emotion analysis was also carried out with the FEEL-IT package (Bianchi et al., 2021) to examine the posts mentioning vaccine skeptics more in-depth. This analysis aimed to compare the sentiments communicated by the news about No-Vaxxers with those of other posts on vaccines (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sentiments by keywords “No vax” (n = 87) and “Vaccine” (n = 2803), row percentages.

The results highlight two distinct patterns. Anger prevails in the news about No-Vaxxers (70.1%), while fear prevails in those on vaccines (66.1%). Therefore, the news about No-Vaxxers frequently tends to focus on the most negative and violent aspects of the movement, as in this post from 14 September 2021, in which threats to a famous singer who has worked to promote vaccination campaigns are reported:

I have received threats from some NO-VAX who want to ‘Search me, beat me, run me over and beat me up’. J-Ax wrote this in a post on Instagram. After contracting Covid, he became the spokesperson for the pro-vaccination campaign.

4. Discussion

In this exploratory study, we quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed the Facebook posts of the Italian National Press Agency (ANSA) on vaccine issues in Italy between 2016 and 2023. We defined two main analysis periods: the ANSA’s posts published between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2019 and those published between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2023. The distinguishing characteristic of this research is its endeavor to trace and study the narrative on vaccinations before, during, and after the pandemic, following two main significant vaccine-related events in the Italian landscape, such as the introduction of childhood vaccination mandates and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The public discussions about and the implementation of childhood vaccination mandates characterized the first period (2016–2019), while the onset and the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, along with the introduction of the anti-COVID-19 vaccines, characterized the subsequent period (2020–2023).

Our analysis reveals (RQ1) that ANSA’s framing of vaccines evolved significantly between the two periods studied—i.e., 2016–2019 and 2020–2023. Initially, vaccines were framed as threatened by misinformation and as a lifesaving practice. During the pandemic, the framing shifted to emphasize vaccines as a scientific achievement and a broader social requirement. This evolution highlights how ANSA adapted its narrative to the changing context, from public health debates to a global health crisis.

Four main narratives characterized ANSA’s framing of the vaccination debate when the “decree Lorenzin” and its legislative enactment (Law No. 119/2017) introduced ten mandatory vaccines for children with sanctions for non-compliance. The first vaccine-related framing saw vaccination as threatened by fake news and anti-vaccination movements. The posts included in this narrative were thus focused on providing accurate information to debunk fake news. This result aligns with what Wagner et al. (2024) found in their cross-country study. Furthermore, this finding is consistent with the broader trend noted by Brunson and Sobo (2017), who observed that vaccination narratives in public discourse are often reduced to polarized binaries, which can obscure more nuanced positions. This pattern was visible in ANSA’s framing, particularly when vaccination opponents were associated with misinformation and disinformation efforts. It is interesting to note that this narrative was also encountered, despite not being predominant, in ANSA’s posts during the COVID-19 pandemic, often explicitly pointing to the No-Vaxxers as the cause of the spread of vaccine-related fake news. Framing vaccination as threatened by fake news, on the one hand, sees parents as passive recipients of information. On the other hand, it reproduces a “deficit (knowledge transmission) model” (Seethaler et al., 2019), where vaccine-hesitant parents are seen as lacking vaccine-related education as well as requiring protection against No-Vaxxers (Court et al., 2021; Goldenberg, 2016). Such media framing choices can increase the accessibility of specific beliefs and may limit the perceived legitimacy of dissenting views (Bullock & Shulman, 2021; Guenther et al., 2020). This may contribute to reduced trust in public health messaging among hesitant individuals.

The second vaccine-related narrative in the 2016–2019 framework is vaccination as a lifesaving practice. ANSA’s news focused mainly on providing information about the role of vaccines in eradicating or controlling several diseases over time. This information supported childhood vaccination and mandates, also reporting cases of children who died or suffered serious health consequences after contracting a vaccine-preventable disease (VPD). As discussed in framing theory, such media strategies can raise public awareness by emphasizing specific health risks and solutions, i.e., vaccination in this case, thereby influencing attitudes and behaviors (Coleman et al., 2011; Yousaf et al., 2022). These ANSA’s posts thus aimed to raise parents’ risk perception regarding VPDs, reinforcing the social value of vaccination and shaping broader health-related risk perception (Kasperson et al., 1988; Kahan, 2014).

The third way ANSA frames the vaccination issue, and particularly its regulation, is as a contentious topic within the broader political sphere. Indeed, childhood vaccination mandates in Italy have witnessed political forces, with the government supporting the new vaccination regulation while the opposition criticized the mandates and/or the sanctions imposed for non-compliance at various levels. This highlights not only that the public debate on vaccines was influenced (besides other factors) by political factors (Bucchi, 2000), but that the political actors involved also actively contributed to its polarization (Casula & Toth, 2018).

The fourth narrative concerning the 2016–2019 period specifically frames vaccination as a requirement for a specific subgroup of the population, i.e., children. The ANSA’s posts discuss the new childhood vaccination requirements and highlight the perceived information and organizational chaos that followed. In particular, the procedures and timelines mandated by Law No. 119/2017 have exerted considerable pressure on both families and healthcare institutions and providers. Indeed, in line with what was highlighted by previous research (Fattorini, 2023), while especially non-compliant families had to find an alternative educational solution for their children, the local vaccination hubs and pediatricians faced significant organizational pressure due to broader personnel shortages in the healthcare sector.

The Italian pandemic and post-pandemic period (2020–2023) was instead characterized by the introduction of non-pharmaceutical restrictions to contain the virus, the anti-COVID-19 vaccines, and the Green Pass. In this context, three main vaccine-related narratives were identified in ANSA news posts. As noted by Wagner et al. (2024), the narratives focused mainly on the anti-COVID-19 vaccination and overlapped the different health science and political phases of the pandemic, as found in Pan and Meng’s (2016) research. Indeed, the pandemic period was characterized by the stages of vaccine discovery, production, legislation, and distribution. The first way in which the vaccination issue was framed was by portraying vaccination as a long-awaited (scientific) achievement. In ANSA’s posts, the great expectation of anti-COVID-19 vaccines emerges, along with discussions and updates concerning their availability—e.g., stipulation of contracts with the pharmaceutical companies—and their efficacy in preventing the most serious consequences of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. As Wagner et al. (2024, p. 6) pointed out, anti-COVID-19 vaccines were expected to be and portrayed as “a passport to a safe future, a chance to return to normality and stabilise national economic and social life”.

The second ANSA narrative frames anti-COVID-19 vaccination as a broader social requirement, emphasizing collective responsibility and the importance of supporting institutional strategies to combat the virus. This finding is consistent with framing theory (Entman, 1993), which posits that the salience of collective responsibility and solidarity in media messaging contributes to shaping public attitudes toward compliance with institutional strategies. ANSA’s pandemic-period coverage frequently leveraged this collective framing, contrasting with its pre-pandemic focus, which primarily emphasized the individual health benefits of vaccination. During and after the pandemic, vaccination was increasingly portrayed as a civic duty and a necessary step to protect the community. This shift aligns with findings by Wagner et al. (2024), who observed that post-pandemic media across Europe often framed vaccination in terms of social cohesion, national recovery, and solidarity. Furthermore, this narrative included regular updates on the progress of the vaccination campaign and the Green Pass certification. Notably, many of the posts focused on the Green Pass’s implementation, as well as public demonstrations and opposition to the measure, especially from certain political groups and professional sectors.

As the pandemic progresses towards its latter stages, a modification has occurred in the ANSA’s vaccine-related narrative. The anti-COVID-19 vaccines were formerly presented as a certain method to end the pandemic. However, with the rise of new SARS-CoV-2 variants, doubts have emerged regarding the vaccines’ efficacy. Therefore, the third narrative portrays vaccination as a tool whose efficacy against the evolution of the virus must be confirmed.

In addressing the portrayals of dissent (RQ2), the findings indicate that ANSA often portrayed vaccine and/or vaccine mandates opponents negatively, particularly during the pandemic. The employment of the “No-Vax” label was pervasive, albeit not predominant, and was frequently linked with misinformation and radical anti-vaccination movements. This narrative strategy aligns with broader trends in media coverage of vaccine hesitancy, where opponents are frequently depicted as a monolithic group rather than a diverse range of individuals with varying levels of hesitancy. Furthermore, our analysis shows that the No-Vax term (RQ3) was used sparingly but carried significant negative connotations. This labeling tends to oversimplify the complexities of vaccine hesitancy and can polarize public discourse.

In ANSA’s coverage of vaccine hesitancy, the No-Vax term has been employed to denote non-compliant parents, individuals who have not received the anti-COVID-19 vaccine or booster doses, and, in a more general sense, those who oppose the policies mandating childhood and/or COVID-19 vaccinations. It should be noted, however, that the number of posts specifically mentioning No-Vax-related terms was very low compared to the number of posts discussing vaccination in general. Contrary to the results by Caroselli and Schiano (2023), even if most of the news about No-Vaxxers was concentrated during the pandemic, the label did not monopolize ANSA’s communication landscape. This might be due to the specific characteristics of ANSA: because of its role as the national independent news provider, its news tends to be presented in more neutral terms—i.e., less politically oriented—than those offered in other news outlets, which instead tend to use ANSA’s news as a basis for developing their articles. Nevertheless, the negative characteristics linked to the “No-Vax” term (Ward et al., 2019) were reproduced in ANSA’s posts, often reporting the most radical representations of anti-vaccination movements. The subsequent sentiment analysis further illuminated the negative connotations associated with the ANSA’s posts that referenced the No-Vax label, predominantly evoking sentiments of anger towards this non-compliant group. Consequently, this label has the potential to obscure the multifaceted nature of vaccine hesitancy and the varying degrees of hesitancy that an individual may hold towards one or multiple vaccines. Given their ability and responsibility to frame issues and shape public opinion and awareness (Kim & Willis, 2007), the news media should engage in more nuanced and respectful communication—e.g., by avoiding using the term “anti-vaxxer” as suggested by Court et al. (2021)—when discussing vaccine skepticism. This recommendation echoes earlier critiques of judgmental narratives in media (Rozbroj et al., 2019), which highlight the importance of tone and framing in maintaining public trust and reducing polarization.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This study specifically examined how ANSA, Italy’s primary news agency, has framed the issue of vaccination over time. While this study provides valuable insight into a key player in the Italian media landscape, it presents a limitation in terms of scope. Future research endeavors should prioritize a comprehensive analysis by incorporating other prominent Italian news outlets to construct a more comprehensive map of national media narratives on vaccination.

Another important research direction involves examining how different social groups interpret and respond to these media frames. A comprehensive understanding of public perception, particularly in relation to polarizing aspects such as pro- or anti-vaccination stances, could illuminate the broader social impact of media messaging and its influence on public opinion.

Extending this research across national borders could offer valuable comparative insights. The execution of comparative studies that analyze framing strategies in different countries could help identify common trends and culturally specific approaches to vaccine communication. This, in turn, could enrich our understanding of the global media landscape during health crises.

Furthermore, this study underscores the media’s potential role in promoting public health policy, particularly through enhanced science and risk communication. Given the power of media narratives to shape public attitudes toward vaccination, future work should emphasize the need for nuanced reporting that reflects the diversity of public concerns and avoids oversimplified or polarizing portrayals. Consequently, future research should explore how different media outlets specifically address vaccine hesitancy and assess the implications of these narratives for public health outcomes.

In summary, while this study provides an exploratory and foundational analysis of ANSA’s vaccine-related coverage, further exploration is necessary to fully understand the implications of our findings. To enhance our comprehension of the impact of media on vaccination discourse, it is imperative to expand the scope of media analysis by incorporating public perception studies and undertaking international comparisons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and E.L.; methodology, E.L.; software, E.L.; validation, E.L.; formal analysis, E.L.; investigation, E.F. and E.L.; resources, E.F.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F. and E.L.; writing—review and editing, E.F. and E.L.; visualization, E.L.; supervision, E.F.; project administration, E.F.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are publicly available. The dataset can be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Decree-Law No. 73 of 7 June 2017, published in the Official Gazette No. 130 of 7 June 2017. |

| 2 | Law No. 119 of 31 July 2017, published in the Official Gazette No. 182 of 5 August 2017. |

| 3 | Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Global Health Security Agenda Action Packages: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/globalhealth/security/actionpackages/immunizationap.htm (accessed on 30 November 2024). |

| 4 | Arts. 1 and 3 of Decree-Law No. 73 of 7 June 2017, published in the Official Gazette No. 130 of 7 June 2017, converted into Law No. 119 of 31 July 2017, published in the Official Gazette No. 182 of 5 August 2017. |

| 5 | See https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_2466 (accessed on 2 December 2024). |

| 6 | See https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/-/aifa-pubblica-il-rapporto-vaccini-2020 (accessed on 2 December 2024). |

| 7 | Law No. 76 of 28 May 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 128 of 31 May 2021; the law was the legislative enactment of the Decree-Law No. 44 of 1 April 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 79 of 1 April 2021. |

| 8 | Decree-Law No. 52 of 22 April 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 96 of 22 April 2021; converted with amendments by Law No. 87 of 17 June 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 146 of 21 June 2021. |

| 9 | Decree-Law No. 105 of 23 July 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 175 of 23 July 2021. |

| 10 | Decree-Law No. 172 of 26 November 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 282 of 26 November 2021. |

| 11 | Decree-Law No. 1 of 7 January 2022, published in the Official Gazette no. 4 of 7 January 2022. |

| 12 | Decree-Law No. 162 of 31 October 2022, published in the Official Gazette no. 255 of 31 October 2022. |

| 13 | Decree-Law 105/2021. |

| 14 | Decree-Law No. 229 of 30 December 2021, published in the Official Gazette no. 309 of 30 December 2021. |

| 15 | According to Traag et al. (2019) Leiden algorithm provides optimal results compared to other methods, such as the Louvain and the Walktrap algorithms. |

| 16 | This analysis was carried out after translating the posts into English. The analysis was carried out through community detection as described in the methodological part considering the individual words as nodes of the network. |

| 17 | All Facebook links were accessed on 24 July 2024. |

| 18 | During the pandemic, Italy was divided into zones with different colors—i.e., green, yellow, and red—implying different restrictions based on the number of infections. The red zone was the strictest one. |

| 19 | This analysis and the subsequent sentiment analysis were carried out directly on the original posts in Italian. |

References

- Alfano, V., Capasso, S., & Limosani, M. (2023). On the determinants of anti-COVID restriction and anti-vaccine movements: The case of IoApro in Italy. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 16784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwell, K., Harper, T., Rizzi, M., Taylor, J., Casigliani, V., Quattrone, F., & Lopalco, P. L. (2021). Inaction, under-reaction action and incapacity: Communication breakdown in Italy’s vaccination governance. Policy Sciences, 54(3), 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, P., & Sharma, C. (2016). Community detection in social networks. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, 6(3), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, A., & Seddone, A. (2021). Italy: Populist in the mirror, (De) politicizing the COVID-19 from government and opposition. In Populism and the politicization of the COVID-19 crisis in Europe (pp. 45–58). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, F., Nozza, D., & Hovy, D. (2021). FEEL-IT: Emotion and Sentiment Classification for the Italian Language. In Proceedings of the eleventh workshop on computational approaches to subjectivity, sentiment and social media analysis (pp. 76–83). Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson, E. K., & Sobo, E. J. (2017). Framing childhood vaccination in the United States: Getting past polarization in the public discourse. Human Organization, 76(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchi, M. (2000). La scienza in pubblico. Percorsi nella comunicazione scientifica. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Bucchi, M., Fattorini, E., & Saracino, B. (2022). Public Perception of COVID-19 Vaccination in Italy: The Role of Trust and Experts’ Communication. International Journal of Public Health, 67, 1604222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, O. M., & Shulman, H. C. (2021). Utilizing framing theory to design more effective health messages about tanning behavior among college women. Communication Studies, 72(3), 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, G., Greenberg, J., Dubé, E., & Driedger, M. (2018). Measles, moral regulation and the social construction of risk: Media narratives of “anti-vaxxers” and the 2015 disneyland outbreak. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroselli, A., & Schiano, P. (2023). “È colpa dei No-Vax!”. Antivaccinismo e panico morale nel discorso della stampa italiana. Studi Sulla Questione Criminale, 1, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casula, M., & Toth, F. (2018). The Yellow-Green government and the thorny issue of childhood routine vaccination. Italian Political Science, 13(2), 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics. The creation of the mods and rockers. MacGibbon and Kee Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, R., Thorson, E., & Wilkins, L. (2011). Testing the effect of framing and sourcing in health news stories. Journal of Health Communication, 16(9), 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Court, J., Carter, S. M., Attwell, K., Leask, J., & Wiley, K. (2021). Labels matter: Use and non-use of ‘anti-vax’ framing in Australian media discourse 2008–2018. Social Science & Medicine, 291, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (1999). Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In G. J. Cizek (Ed.), Handbook of educational policy (pp. 455–472). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- CrowdTangle Team. (2023). CrowdTangle. Facebook, Menlo Park, California, United States. CrowdTangle Team. [Google Scholar]

- Csárdi, G., Nepusz, T., Traag, V., Horvát, S., Zanini, F., Noom, D., & Müller, K. (2024). igraph: Network analysis and visualization in R. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7682609, R package version 2.0.3. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=igraph (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Della Porta, D., & Lavizzari, A. (2022). Waves in cycle: The protests against anti-contagion measures and vaccination in COVID-19 times in Italy. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 15(3), 720–740. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, E., Laberge, C., Guay, M., Bramadat, P., Roy, R., & Bettinger, J. A. (2013). Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini, E. (2023). Rediscussing The Primacy of Scientific Expertise: A Case Study on Vaccine Hesitant Parents in Trentino. Tecnoscienza—Italian Journal of Science & Technology Studies, 14(1), 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini, E., & Balazka, B. (2025). Is Religion Bad for You? Vaccine Hesitancy and Religiosity in the Pandemic Context. In M. Giansoldati (Ed.), Pandemia e vaccinazioni Aspetti economici, sociali e politici nel caso del COVID-19 (pp. 145–174). Edizioni Università di Trieste. [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman, S., Mishra, S., Gandy, A., Unwin, H. J. T., Mellan, T. A., Coupland, H., Whittaker, C., Zhu, H., Berah, T., Eaton, J. W., Monod, M., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, Ghani, A. C., Donnelly, C. A., Riley, S., Vollmer, M. A. C., Ferguson, N. M., Okell, L. C., & Bhatt, S. (2020). Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature, 584(7820), 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobo, G., & Sena, B. (2022). Questioning and disputing vaccination policies. scientists and experts in the Italian public debate. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 42(1–2), 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M. J. (2016). Public misunderstanding of science? Reframing the problem of vaccine hesitancy. Perspectives on Science, 24(5), 552–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, L., Gaertner, M., & Zeitz, J. (2020). Framing as a concept for health communication: A systematic review. Health Communication, 36(7), 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolfi, C., & Spaccarotella, C. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy. JACC: Case Reports, 2(9), 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D. M. (2014). Vaccine risk perceptions and ad hoc risk communication: An empirical assessment. CCP Risk Perception Studies Report No. 17, Yale Law & Economics Research Paper, 491. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2386034 (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Goble, R., Kasperson, J. X., & Ratick, S. (1988). The Social Amplification of Risk: A Conceptual Framework. Risk Analysis, 8(2), 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., & Willis, A. L. (2007). Talking about obesity: News framing of who is responsible for causing and fixing the problem. Journal of Health Communication, 12(4), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, M., & Fairhead, J. (2007). Vaccine anxieties: Global science, child health and society. Earthscan. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. (2012). Sentiment analysis and opinion mining. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Loner, E., Fattorini, E., & Bucchi, M. (2023). The role of science in a crisis: Talks by political leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 18(3), e0282529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovari, A., Martino, V., & Righetti, N. (2021). Blurred shots: Investigating the information crisis around vaccination in Italy. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N. E., Eskola, J., Liang, X., Chaudhuri, M., Dube, E., Gellin, B., Goldstein, S., Larson, H., Manzo, M. L., Reingold, A., Tshering, K., Zhou, Y., Duclos, P., Guirguis, S., Hickler, B., & Schuster, M. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Digital news report 2024. Reuters Institute, University of Oxford. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Odone, A., Dallagiacoma, G., Frascella, B., Signorelli, C., & Leask, J. (2021). Current understandings of the impact of mandatory vaccination laws in Europe. Expert Review of Vaccines, 20(5), 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odone, A., Tramutola, V., Morgado, M., & Signorelli, C. (2018). Immunization and media coverage in Italy: An eleven-year analysis (2007-17). Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(10), 2533–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.-L., & Meng, J. (2016). Media frames across stages of health crisis: A crisis management approach to news coverage of flu pandemic. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 24(2), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozbroj, T., Lyons, A., & Lucke, J. (2019). The mad leading the blind: Perceptions of the vaccine-refusal movement among Australians who support vaccination. Vaccine, 37(40), 5986–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seethaler, S., Evans, J. H., Gere, C., & Rajagopalan, R. M. (2019). Science, values, and science communication: Competencies For pushing beyond the deficit model. Science Communication, 41(3), 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, M. (2016). Sentiment analysis: An overview from linguistics. Annual Review of Linguistics, 2(1), 325–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traag, V. A., Waltman, L., & Van Eck, N. J. (2019). From louvain to leiden: Guaranteeing well-connected communities. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A., Polak, P., Rudek, T. J., Świątkiewicz-Mośny, M., Anderson, A., Bockstal, M., Gariglio, L., Marhánková, J. H., Hilário, A. P., Hobson-West, P., Iorio, J., Kuusipalo, A., Numerato, D., Scavarda, A., da Silva, P. A., Moura, E. S., & Vuolanto, P. (2024). Agency in urgency and uncertainty. Vaccines and vaccination in European media discourses. Social Science & Medicine, 346, 116725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. K., Guille-Escuret, P., & Alapetite, C. (2019). Les « antivaccins », figure de l’anti-Science. Déviance et Société, 43(2), 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, K. E., Leask, J., Attwell, K., Helps, C., Barclay, L., Ward, P. R., & Carter, S. M. (2021). Stigmatized for standing up for my child: A qualitative study of non-vaccinating parents in Australia. SSM—Population Health, 16, 100926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, K., Given, L. M., & Scifleet, P. (2018). Qualitative data analysis. In K. Williamson, & G. Johanson (Eds.), Research methods: Information, systems, and contexts (2nd ed., pp. 453–476). Chandos Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, M., Hassan Raza, S., Mahmood, N., Core, R., Zaman, U., & Malik, A. (2022). Immunity debt or vaccination crisis? A multi-method evidence on vaccine acceptance and media framing for emerging COVID-19 variants. Vaccine, 40(12), 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).