Burnout in Pediatric Oncology: Team Building and Clay Therapy as a Strategy to Improve Emotional Climate and Group Dynamics in a Nursing Staff

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- ‑

- Literature review to investigate the phenomenon, with focus on pediatric oncology-hematology areas;

- ‑

- Assessment (T0) of the degree of nursing staff burnout, alexithymia, and emotional dysregulation by validated screening tests (MBI, TAS-20, DERS);

- ‑

- Implementation of team-building through clay therapy with two monthly meetings for the nursing team (10 total);

- ‑

- Final evaluation (T1) of how the variables under study changed.

2.1. Participants

2.2. Tools

2.3. The Art-Out Project

2.4. Statistical Analysis

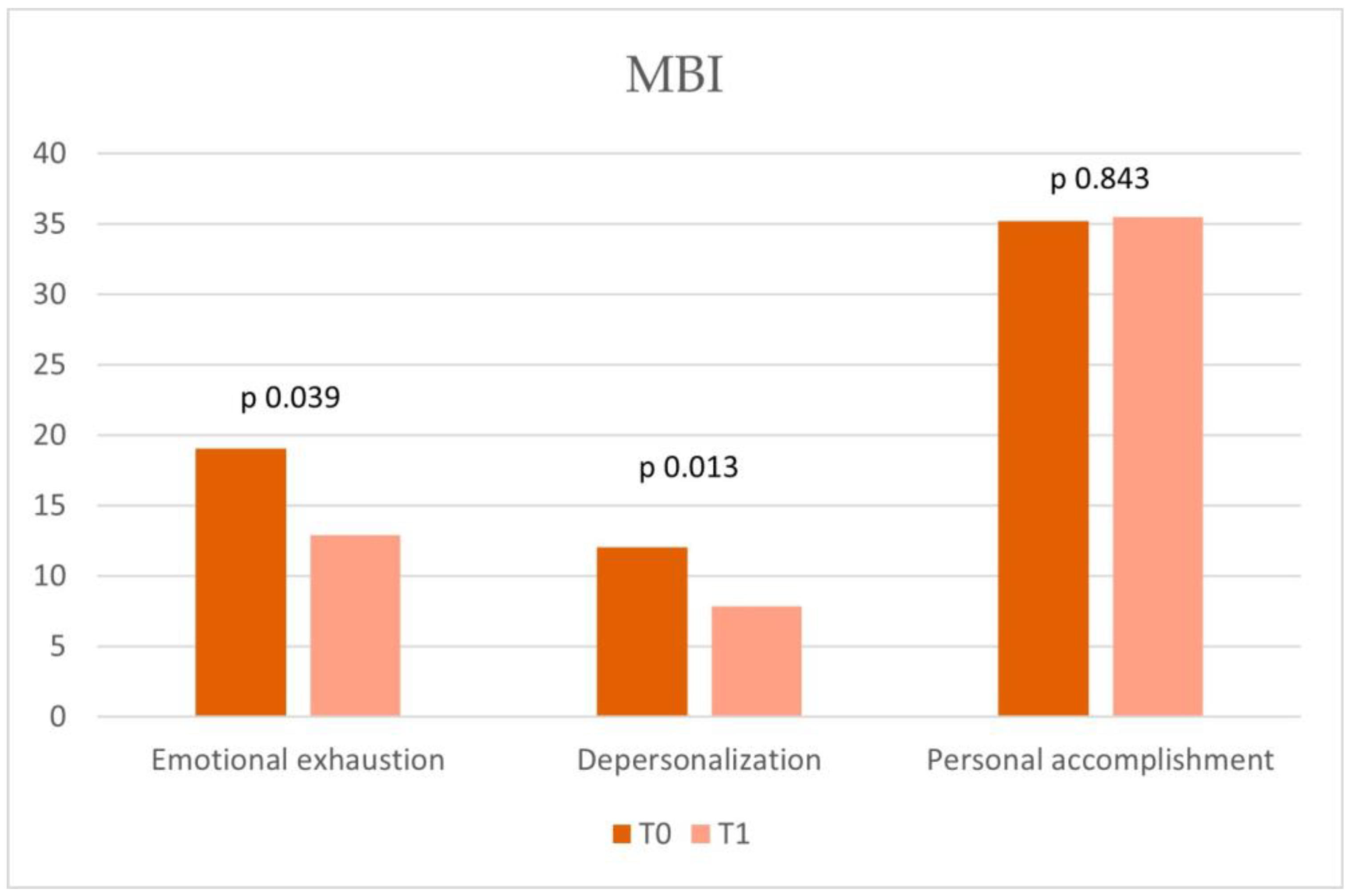

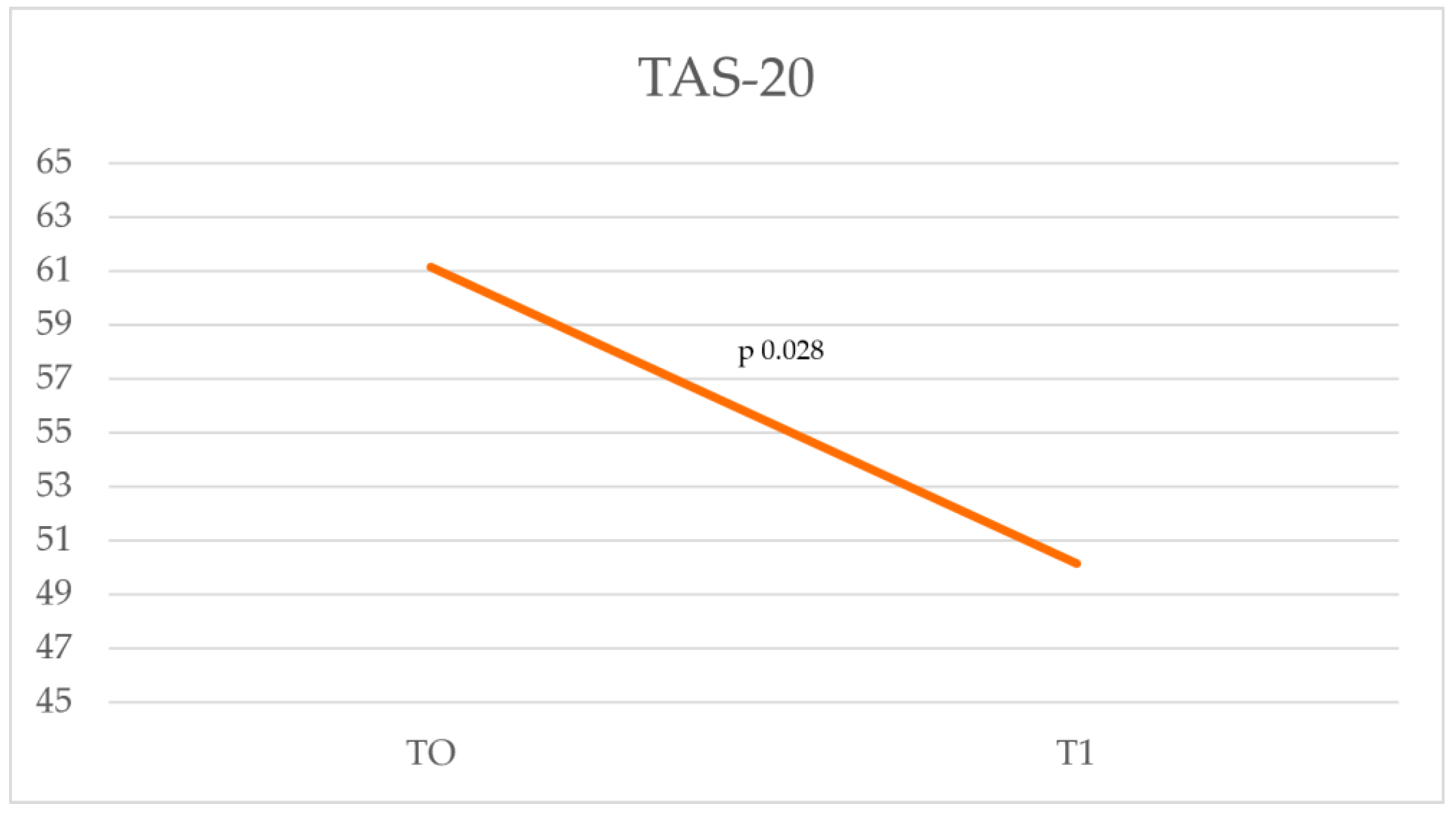

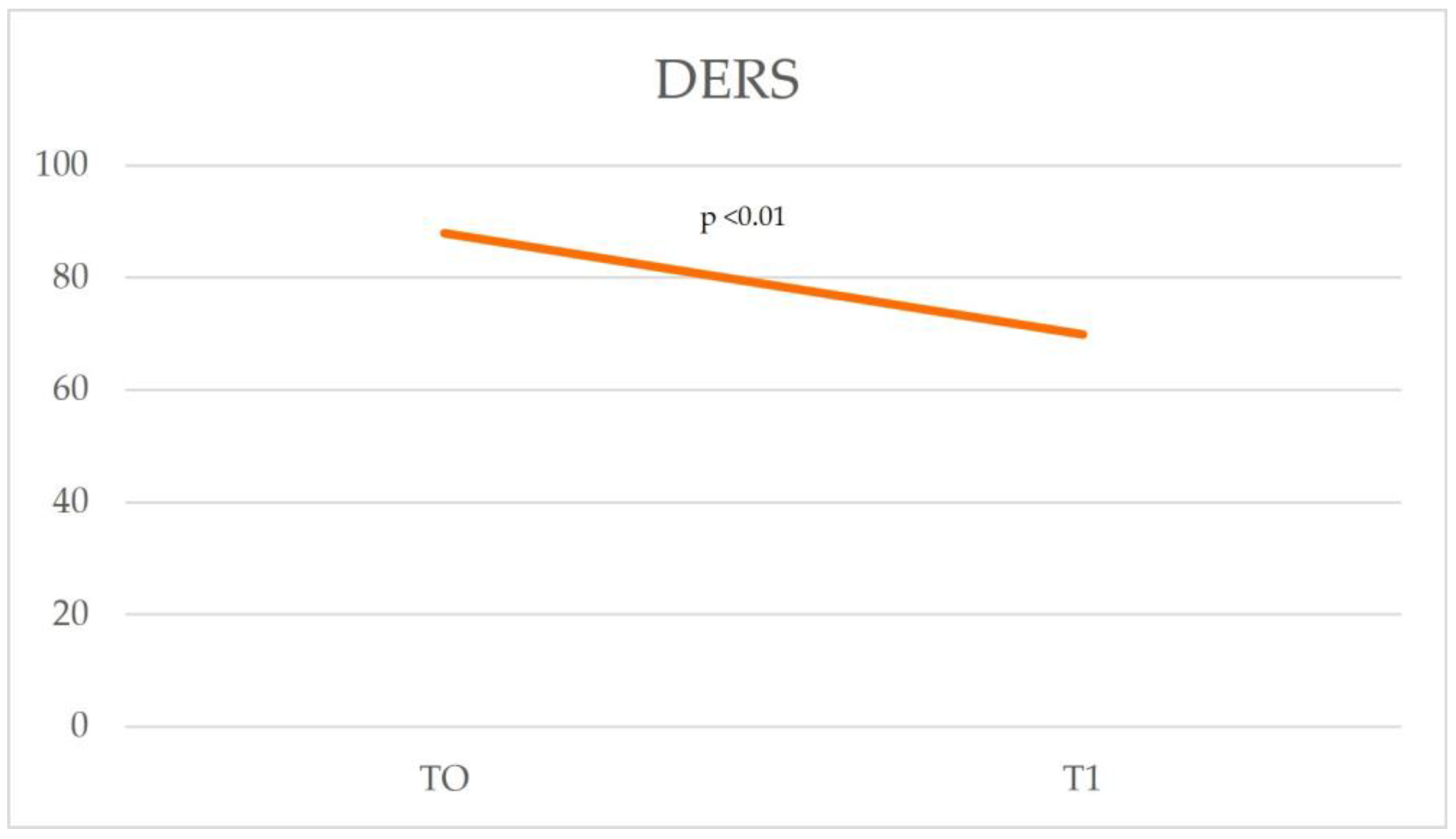

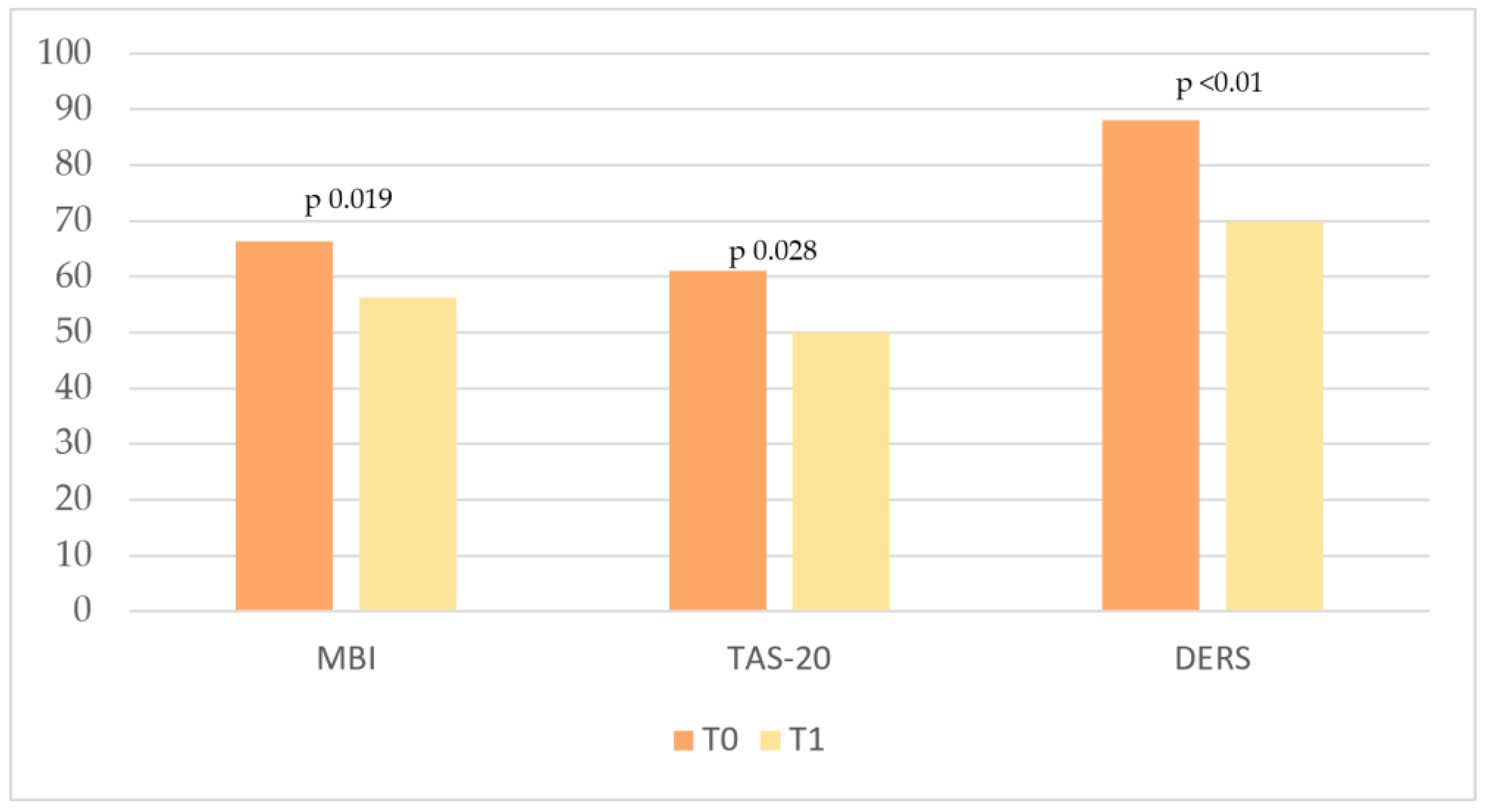

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Pradas-Hernández, L.; Ramiro-Salmerón, A.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Albendín-García, L.; la Fuente, G.A.C.-D. Burnout syndrome in paediatric oncology nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare 2020, 8, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, F. La Sindrome del Burn-Out; Centro Scientifico: Torino, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sidoti, E.; Arcoleo, A.; Tringali, G.; Batista, N.A.; Sonzogno, M.C. Supportive care in a paediatric onco-haematological service: Therapeutic patient education and burn-out prevention in health workers. Support. Palliat. Cancer Care 2006, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bolwerk, A.; Mack-Andrick, J.; Lang, F.R.; Dörfler, A.; Maihöfner, C. How art changes your brain: Differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, M.M.Y.; Saini, B.; Smith, L. Using drawings to explore patients’ perceptions of their illness: A scoping review. J. Multidiscip. Health 2016, 9, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, H.L.; Nobel, J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: A review of current literature. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portoghese, I.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Galletta, M.; Porru, F.; D’Aloja, E.; Finco, G.; Campagna, M. Measuring Burnout Among University Students: Factorial Validity, Invariance, and Latent Profiles of the Italian Version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Student Survey (MBI-SS). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.; Leiter, M. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bressi, C.; Taylor, G.; Parker, J.; Bressi, S.; Brambilla, V.; Aguglia, E.; Allegranti, I.; Bongiorno, A.; Giberti, F.; Bucca, M.; et al. Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. J. Psychosom. Res. 1996, 41, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sighinolfi, C.; Norcini Pala, A.; Chiri, L.R.; Marchetti, I.; Sica, C. Traduzione e adattamento italiano del Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Strategies (DERS): Una ricerca preliminare. Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2010, 16, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tjasink, M.; Keiller, E.; Stephens, M.; Carr, C.E.; Priebe, S. Art therapy-based interventions to address burnout and psychosocial distress in healthcare workers—A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HaGani, N.; Yagil, D.; Cohen, M. Burnout among oncologists and oncology nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2022, 41, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Calderon, J.; Infante-Cano, M.; Casuso-Holgado, M.J.; García-Muñoz, C. The prevalence of burnout in oncology professionals: An overview of systematic reviews with meta-analyses including more than 90 distinct studies. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italia, S.; Favara-Scacco, C.; Di Cataldo, A.; Russo, G. Evaluation and art therapy treatment of the burnout syndrome in oncology units. Psycho-Oncology 2007, 17, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, R.O.; Hietanen, P.; Elmusrati, M.; Youssef, O.; Almangush, A.; Mäkitie, A.A. Mitigating Burnout in an Oncological Unit: A Scoping Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 677915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riethof, N.; Bob, P.; Laker, M.; Zmolikova, J.; Jiraskova, T.; Raboch, J. Alexithymia, traumatic stress symptoms and burnout in female healthcare professionals. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519887633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Berardis, D.; Ceci, A.; Zenobi, E.; Rapacchietta, D.; Pisanello, M.; Bozzi, F.; Ginaldi, L.; Marasco, V.; Di Giosia, M.; Brucchi, M.; et al. Alexithymia, Burnout, and Hopelessness in a Large Sample of Healthcare Workers during the Third Wave of COVID-19 in Italy. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, M.; Tesio, V.; Bertholet, J.; Gasnier, A.; del Portillo, E.G.; Spalek, M.; Bibault, J.-E.; Borst, G.; Van Elmpt, W.; Thorwarth, D.; et al. Professional quality of life and burnout among medical physicists working in radiation oncology: The role of alexithymia and empathy. Phys. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Hossaini, S.M. The Relationship of Spiritual Health with Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Burnout: The Mediating Role of Emotional Regulation. Iran J. Psychiatry 2018, 13, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maffett, A.J.; Paull, D.N.; Skeel, R.L.; Kraysovic, J.N.; Hatch, B.; O’Mahony, S.; Gerhart, J.I. Emotion Dysregulation and Workplace Satisfaction in Direct Care Worker Burnout and Abuse Risk. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haymaker, C.M.; Bane, C.M.; Roise, A.; Greene, J. Emotion Regulation and Burnout in Family Medicine Residents. Fam. Med. 2022, 54, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, D.; Edwards, D.; Hannigan, B.; Fothergill, A.; Burnard, P. A systematic review of stress among mental health social workers. Int. Soc. Work. 2005, 48, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Beresford, B.; Glaser, A.; Sloper, P. Burnout, psychiatric morbidity, and work-related sources of stress in paediatric oncology staff: A review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 18, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, A.S.; Sarosi, A.; Goldberg, E.; Waldman, E.D. A Cross-sectional Analysis of Compassion Fatigue, Burnout, and Compassion Satisfaction in Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Physicians in the United States. J. Pediatr. Hematol. 2020, 42, e50–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, P. A critical ethnographic evaluation of pediatric haematology/oncology physicians and burn-out. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 37, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinetta, J.J.; Jankovic, M.; Ben Arush, M.W.; Eden, T.; Epelman, C.; Greenberg, M.L.; Martins, A.G.; Mulhern, R.K.; Oppenheim, D.; Masera, G. Guidelines for the Recognition, Prevention, and Remediation of Burnout in Health Care Professionals Participating in the Care of Children with Cancer: Report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2000, 35, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Morrone, K.; Moody, K.; Kim, M.; Wang, D.; Moadel, A.; Levy, A. Career burnout among pediatric oncologists. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2011, 57, 1168–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, M.J.; Mukherjee, S.; Williams, L.K.; DeGraves, S.; Jackson, M.; McCarthy, M.C. Work-related stress and reward: An Australian study of multidisciplinary pediatric oncology healthcare providers. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P.J.; Edwards, R.M. Needs analysis and development of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group. J. Health Leadersh. 2018, 10, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, P.J.; Edwards, R.M.; Badat, A. Evaluation of a staff well-being program in a pediatric oncology, hematology, and palliative care services group. J. Health Leadersh. 2018, 10, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, K.; Kramer, D.; Santizo, R.O.; Magro, L.; Wyshogrod, D.; Ambrosio, J.; Castillo, C.; Lieberman, R.; Stein, J. Helping the helpers: Mindfulness training for burnout in pediatric oncology—A pilot program. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 30, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | N (%) | Means ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 43.31 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 (7.7) | |

| Female | 12 (92.3) | |

| Role in pediatric oncology | ||

| Nurse | 13 (100) | |

| Professional seniority | ||

| 0–10 | 5 (38.5) | |

| 11–20 | 0 | |

| >20 | 8 (38.5) | |

| Professional seniority in pediatric oncology | ||

| 0–10 | 6 (46.1) | |

| 11–20 | 4 (30.8) | |

| >20 | 3 (23.1) | |

| Psychotherapy | ||

| Yes, still in progress | 1 (7.7) | |

| Yes, in the past | 3 (23.1) | |

| No, never | 9 (69.2) |

| Factors | Baseline Means (SD) | Follow-Up Means (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | 19.077 (8.827) | 12.92 (3.61) | 0.039 |

| Depersonalization | 12.077 (4.132) | 7.846 (3.555) | 0.013 |

| Personal accomplishment | 35.231 (1.964) | 35.53 (5.12) | 0.843 |

| Total score MBI | 66.8 (11.41) | 56.296 (7.2) | 0.019 |

| MBI Scale Test | Cut-Off |

|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | High risk ≥ 30 Medium risk 18–29 Low risk ≤ 17 |

| Depersonalization | High risk ≥ 12 Medium risk 6–11 Low risk ≤ 5 |

| Personal accomplishment | High risk ≤ 33 Medium risk 34–39 Low risk ≥ 40 |

| Baseline Means (SD) | Follow-Up Means (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score TAS 20 | 61.15 (8.93) | 50.15 (11.82) | 0.028 |

| Baseline Means (SD) | Follow-Up Means (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Acceptance | 13.923 (4.555) | 12.385 (3.453) | 0.616 |

| Goals | 12.846 (4.543) | 11.538 (2.696) | 0.714 |

| Strategies | 22.923 (2.290) | 20.231 (2.351) | 0.009 |

| Impulse | 11.385 (3.798) | 10.538 (2.602) | 0.760 |

| Awareness | 13.231 (1.235) | 9.231 (3.492) | 0.001 |

| Clarity | 13.692 (1.601) | 5.923 (2.397) | <0.001 |

| Total score DERS | 88 (9.10) | 69.85 (10.04) | <0.01 |

| Baseline Means (SD) | Follow-Up Means (SD) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBI | 66.38 (11.41) | 56.296 (7.2) | 0.019 |

| TAS-20 | 61.15 (8.93) | 50.15 (11.82) | 0.028 |

| DERS | 88 (9.10) | 69.85 (10.04) | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guido, A.; Peruzzi, L.; Tibuzzi, M.; Sannino, S.; Dario, L.; Petruccini, G.; Stella, C.; Viteritti, A.M.; Becciu, A.; Bianchini, F.; et al. Burnout in Pediatric Oncology: Team Building and Clay Therapy as a Strategy to Improve Emotional Climate and Group Dynamics in a Nursing Staff. Cancers 2025, 17, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071099

Guido A, Peruzzi L, Tibuzzi M, Sannino S, Dario L, Petruccini G, Stella C, Viteritti AM, Becciu A, Bianchini F, et al. Burnout in Pediatric Oncology: Team Building and Clay Therapy as a Strategy to Improve Emotional Climate and Group Dynamics in a Nursing Staff. Cancers. 2025; 17(7):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071099

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuido, Antonella, Laura Peruzzi, Matilde Tibuzzi, Serena Sannino, Lucia Dario, Giulia Petruccini, Caterina Stella, Anna Maria Viteritti, Antonella Becciu, Francesca Bianchini, and et al. 2025. "Burnout in Pediatric Oncology: Team Building and Clay Therapy as a Strategy to Improve Emotional Climate and Group Dynamics in a Nursing Staff" Cancers 17, no. 7: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071099

APA StyleGuido, A., Peruzzi, L., Tibuzzi, M., Sannino, S., Dario, L., Petruccini, G., Stella, C., Viteritti, A. M., Becciu, A., Bianchini, F., Cucculelli, D., Di Lauro, C., Paglialonga, I., Pianezzi, S., Pistilli, R., Russo, S., Adamo, P., Chieffo, D. P. R., Talloa, D., ... Ruggiero, A. (2025). Burnout in Pediatric Oncology: Team Building and Clay Therapy as a Strategy to Improve Emotional Climate and Group Dynamics in a Nursing Staff. Cancers, 17(7), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071099