1. Introduction

In the past half-century, industrial heritage has emerged as a significant and increasingly prominent category within the broader discourse of cultural heritage. In contrast to the architectural legacies of medieval Europe or ancient China, industrial heritage does not conform to classical orders nor does it possess the aura of antiquity. Nevertheless, it has assumed a pivotal role in the reconfiguration of urban spatial structures and has garnered recognition across diverse social strata. From New York’s SoHo district and Sydney’s harbor precinct to the New Territories of Hong Kong and the tin mines of Kuala Lumpur; from the concession-era landscapes of Shanghai to the colonial industrial architecture of Mumbai; from the near-deserted aircraft manufacturing complexes of Tashkent to the innumerable mills, railways, and factories scattered across Europe—these sites collectively chart the technological trajectory of human civilization since the First Industrial Revolution. More importantly, they continue to imbue contemporary urban environments with both historical resonance and cultural significance. It is apparent that from Liverpool, Düsseldorf, and Rotterdam to New York, Buenos Aires, and subsequently to Shanghai, Taipei, Tokyo, Jakarta, Mumbai, Tashkent, and even as far as Pretoria, the aesthetic significance of industrial heritage has garnered global recognition. This phenomenon reflects an emerging international consensus regarding the value of aesthetic objects, increasingly leveraged in urban regeneration initiatives and the cultural and creative industries. Nevertheless, a fundamental question persists: What precisely constitutes the aesthetic value of industrial heritage?

Here, two concepts require clarification: artistic value and aesthetic value. Artistic value is often objective, whereas aesthetic value is subjective. Furthermore, Artistic value emphasizes the originality, stylistic sophistication, and technical mastery embodied in heritage as man-made artworks. Its evaluative criteria are typically associated with notions of “genius,” “uniqueness,” and “irreplaceability”, qualities exemplified by the carvings of Gothic cathedrals or the murals of Baroque palaces. Aesthetic value, by contrast, denotes a broader interplay between subject and object, a synthesis of perceptual and emotional engagement. Heritage attains aesthetic value insofar as it elicits sensory pleasure, emotional resonance, or cultural imagination in the viewer, without necessarily achieving the status of an artistic masterpiece. Within the context of industrial heritage, these two dimensions often diverge: a factory building may lack “artistic originality,” yet still evoke a profound aesthetic response through its monumental scale, material texture, and spatial atmosphere. Beijing’s Shougang blast furnace, for instance, may not embody artistic invention, but its imposing industrial form offers visitors a uniquely compelling aesthetic experience.

This prompts a critical inquiry: wherein lies the aesthetic value of industrial heritage? From a comparative and cross-cultural standpoint, the aesthetic dimension of heritage may be understood as comprising both intrinsic (internal) attributes and extrinsic (external) manifestations [

1]. First, the uniqueness of cultural heritage lies in its capacity to foster a shared cultural identity within a community—whether defined by ethnicity, region, or nation. Iconic sites such as the Forbidden City in Beijing for the Chinese or the pyramids for the Egyptians exemplify how heritage can crystallize collective identity. This function is especially salient in identity-driven nations such as China. A second dimension involves the recognition and appreciation of cultural achievements beyond one’s own tradition, such as Japan’s admiration for Indian culture or China’s appreciation for the Italian Renaissance. Such recognition reflects a crucial aspect of cross-cultural exchange: the acknowledgment of the universal values embodied in human culture. Indeed, the enduring cultural heritage of any nation is ultimately perceived as part of the evolutionary trajectory of human civilization, which provides the aesthetic foundation for the global recognition of world cultural heritage.

In contrast, the aesthetic value of industrial heritage remains more elusive and arguably more complex. At first glance, industrial heritage appears to lack the defining qualities of other forms of heritage: it neither highlights a unique collective identity (as seen in the nearly indistinguishable blast furnaces of Beijing and Pittsburgh), nor does it readily facilitate cross-cultural dialogue. As a testament to the global diffusion of industrial technologies, it is characterized by standardization rather than diversity, by uniformity rather than local particularity.

A key reason for this lies in the fact that, although industrial heritage is a subset of cultural heritage, it bears distinctive traits, chief among them its need to be preserved through ongoing renewal. This marks a clear departure from traditional cultural heritage and aligns it more closely with modern architectural heritage. A crucial point is that industrial heritage is largely expressed through architectural remains. When considering the aesthetics of industrial heritage, we should not overlook the broader framework of heritage aesthetics (such as the aesthetics of ruins). Yet, we must also emphasize the functional dimension of industrial heritage—namely, that its aesthetic value is realized through adaptive reuse.

Although its aesthetic dimensions may be approached from perspectives such as ruin aesthetics, technological aesthetics, nostalgic aesthetics, or steampunk aesthetics, these remain largely descriptive and insufficient. A more systematic theoretical framework is needed to explain why industrial heritage possesses aesthetic value in the first place. In this respect, industrial heritage is no different from other forms of architectural heritage: to comprehend its cultural significance, we must first clarify the basis of our affective attachment to it.

Ultimately, the aesthetic value of industrial heritage constitutes a pressing cultural question, as it is integral to our broader understanding of its core significance. Yet, research in this area remains limited. For instance, the potential of industrial heritage landscapes to serve as powerful instruments for social education has only begun to be recognized, leaving substantial room for further scholarly exploration [

2], some scholars contend that industry attains the status of a “landscape” only after being reinterpreted and reshaped through artistic practices [

3]. Others, however, argue that industry itself emerges from the interplay—if not collusion—of politics, economics, and technology, and therefore the aesthetics of industrial heritage are inherently political in nature [

4] (p 178). A further perspective, drawing on the example of Warsaw’s industrial heritage, emphasizes that the lived experiences of the original community residents constitute a vital aesthetic dimension of industrial heritage [

5].

Industrial heritage sites are widely distributed across the globe, yet their appearances are highly homogenized. This very uniformity provides a unique opportunity to explore the aesthetic value of industrial heritage, as there is still a notable absence of comparative research in this field. To illustrate, the way Americans—including immigrant populations—perceive the material legacies of the Westward Expansion differs significantly from how Britons interpret the architectural heritage of the Charles I era. By contrast, the experiential difference between a Chinese observer at the steel blast furnaces of Beijing Shougang and an American observer at the furnaces of Ohio is comparatively minimal.

This study concentrates on China’s industrial heritage, as the country stands as the world’s largest industrial producer and possesses an extensive array of industrial heritage sites. More importantly, China is home to over 7000 years of continuous civilization. As the world’s largest agricultural nation, its people have long cultivated aesthetic sensibilities deeply rooted in agrarian traditions and clan-based values. Today, however, they exhibit a remarkable enthusiasm for industrial heritage, making China the most active country globally in the adaptive reuse of industrial sites. I contend that examining the aesthetic value of China’s industrial heritage provides a crucial lens through which to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the aesthetic significance of industrial heritage worldwide.

China possesses an exceptionally large quantity of industrial heritage, far exceeding that of the United States. Two main factors account for this phenomenon. First is demographic scale: China’s population is approximately five times that of the United States and three times that of the European Union, necessitating an immense scale of industrial production to sustain daily life. Second is the legacy of the Maoist planned economy, which mandated the establishment of nearly self-sufficient industrial systems in every city [

6]. These systems included not only heavy industry but also factories for rubber, bearings, plastics, textiles, light bulbs, locks, and radios. In effect, each city functioned like an economically independent European principality, equipped with planning committees, material bureaus, and industrial bureaus that allocated resources for both daily consumption and institutional operations. This management approach evolved from wartime rationing mechanisms and, while highly centralized, significantly accelerated China’s industrialization.

With the decline of the Maoist system, the rise of coastal economic zones, and the transformations brought by the Third Industrial Revolution, much of this production space became redundant, giving rise to a vast inventory of industrial heritage. For a considerable period, however, such heritage was left unused, primarily because its economic value was unrecognized. From the early years of Jiang Zemin’s administration through the early years of Xi Jinping’s administration, China’s rapid economic growth and urban renewal—driven largely by the real estate sector—led to the demolition of many factories and, with them, the disappearance of substantial portions of industrial heritage. In this context, neither the economic nor the aesthetic value of industrial heritage was acknowledged.

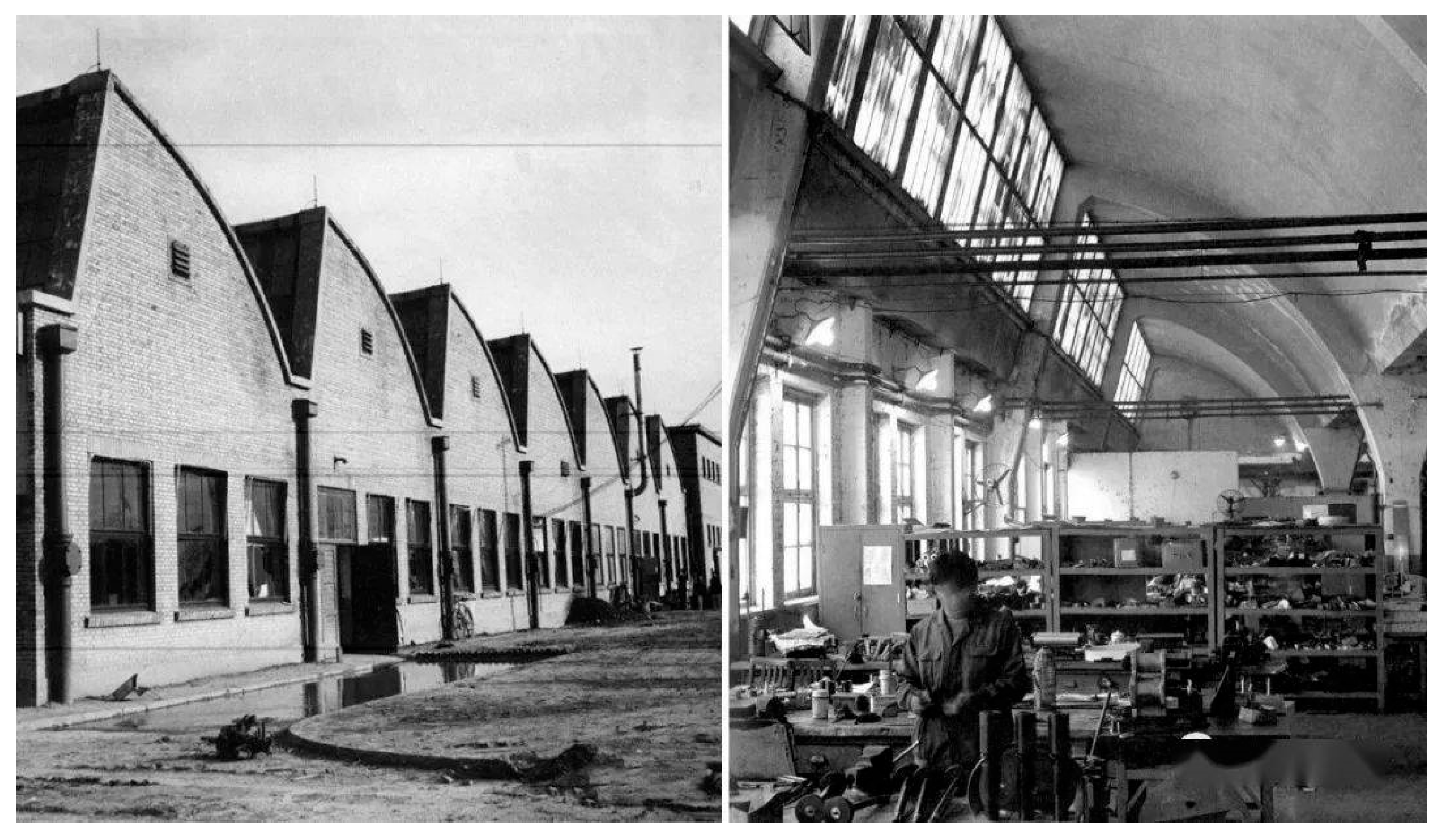

Beijing’s 798 Art District marked a milestone in the adaptive reuse of industrial heritage in China. Originally constructed in the 1950s as part of socialist bloc cooperation, the factory complex was built with the assistance of East Germany, an industrial power at the time, and designed in the Bauhaus style favored by German architects (

Figure 1). During the Cold War, the factory was nationalized under military control and designated with the code “798,” which later became its popular name. During 1990s, however, its products were rapidly rendered obsolete, and the factory eventually went bankrupt. The abandoned site subsequently attracted a group of Chinese artists—many with international experience—who converted the spacious workshops into studios and exhibition spaces. One key reason was practical: contemporary art forms such as oil painting, sculpture, and installation art require expansive spaces and high ceilings, conditions ideally met by the former industrial structures [

7]. Thus, the 798 complex became both a symbol of China’s industrial past and a pioneering example of how industrial heritage could be reimagined through cultural and aesthetic practices.

It is widely acknowledged that the 2008 Beijing Olympics marked a turning point in the globalization of Chinese culture. Prior to that moment, the relationship between Chinese and Western cultures was largely characterized by confrontation and mutual estrangement [

8]. The Western world knew relatively little about China beyond selective representations in films by directors such as Michelangelo Antonioni or Bernardo Bertolucci, or else reduced the country to the image of a vast global factory. Yet, by that time, China’s reform and opening-up policies had already been in place for three decades. Against this backdrop, Chinese leaders began to emphasize the importance of cultural soft power, recognizing that as a nation with a rich and enduring history, China’s cultural resources must not only serve domestic purposes but also function as a catalyst for international engagement and economic development. In line with this vision, Beijing launched ambitious urban renewal projects, designating the 798 Art District as a flagship site for cultural exchange in contemporary Chinese art—a strategy clearly inspired by precedents such as New York’s SoHo district.

Under Xi Jinping’s administration, industrial heritage has received unprecedented national attention. Across the country, large numbers of industrial heritage sites have been transformed into cultural and creative parks, shared community spaces, recreational parks, or new industrial complexes—an occurrence without historical precedent in China. According to our data, as of August 2025, there were over 3000 industrial heritage zones either completed or under construction nationwide. This figure surpasses the combined total of North America and Europe. Moreover, the scope of China’s industrial heritage is remarkably comprehensive, encompassing nearly every category of industrial production, a breadth that reflects the scale and diversity of China’s industrial capacity and technological standards.

Given the ongoing debate over whether industrial heritage possesses distinctive aesthetic value—often dismissed as too standardized, utilitarian, or politically constructed—China’s large-scale practices of adaptive reuse provide a particularly illuminating case through which to revisit and reconceptualize this issue.

For these reasons, China’s industrial heritage and its adaptive reuse constitute a compelling research subject, not only because of their sheer volume but also because they have already formed a relatively stable, market-oriented system. From the industrial heartlands of Northeast China to Beijing, Shanghai, Wuhan, and Shenzhen in the south, as well as Xi’an and Urumqi in the northwest and Kunming and Chengdu in the southwest, industrial heritage reuse projects have proliferated. The direct and indirect economic benefits generated by these projects have become an increasingly significant component of local governments’ urban renewal strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

The primary materials for this research derive from more than a decade of continuous tracking and investigation of over 100 industrial heritage sites across China, combined with an in-depth understanding of more than 50 industrial heritage renovation projects. This engagement encompasses, but is not limited to, participation in the deliberation and formulation of preliminary planning proposals; serving as consultants to local governments or enterprises for assessing project feasibility in the early stages; leading the design of renovation and operational plans; and evaluating the subsequent outcomes of these projects. These endeavors have yielded a substantial corpus of research material for this study.

This corpus includes several key components: first, publicly accessible feasibility reports and planning proposals; second, publicly disclosed operational data of the projects; and third, information pertaining to the projects as documented in official records, local chronicles, and news media.

Methodologically, this study adopts a multi-method qualitative approach grounded in the interpretive constructivist paradigm, emphasizing the analysis of meaning-making and social practices. Specifically, it integrates case studies, field investigations, policy text analysis, and archival/documentary research—thus combining theoretical analysis with empirical investigation.

3. Heritage Aesthetics: Understanding the Overall Aesthetic Characteristics of Cultural Heritage

When discussing the aesthetics of industrial heritage, one must inevitably address “heritage aesthetics,” a concept of paramount importance. Generally speaking, the value of cultural heritage lies in its historical and cultural significance—what period of history it witnessed and what cultural connotations it embodies. Whether it possesses aesthetic value, however, is rarely considered a core aspect of cultural heritage, as “attractiveness” seems relatively unimportant for such sites.

Over the past one century, with the rise of heritage tourism, the aesthetics of cultural heritage have gained prominence as a key factor in attracting visitors. People often show great interest in “visually appealing” historical landscapes. This “appeal” is largely subjective, as individual aesthetic standards vary. Whether beauty is subjective or objective remains a long-debated issue in global aesthetics. However, from the perspective of standardization in tourism and heritage management, the aesthetics of cultural heritage still possess a degree of objectivity, largely determined by universality. For instance, in the World Heritage Convention and UNESCO criteria, expressions closest to “shared or widely accessible aesthetic appeal” include: “a masterpiece of human creative genius” (Criterion i), “an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates a significant stage in human history” (Criterion ii), and “a site of outstanding architectural or landscape beauty” (Criterion iv, also referenced in vi).

However, in practice, heritage aesthetics should encompass more specific dimensions in its criteria. Scholars hold varying perspectives on this issue, such as formal beauty (e.g., composition, proportion, ornamentation) [

9], (pp. 1000–1010) artistic style and level [

10], artistic conception and sensory experience [

11], historical and cultural aesthetic significance [

12], (pp. 339–356) and the widely recognized integrity and authenticity [

13]. In fact, these diverse dimensions collectively form the varied criteria of heritage aesthetics. While we acknowledge that the value of heritage aesthetics is difficult to fully quantify—especially in cross-cultural contexts—this does not negate the existence or significance of these standards. They help society establish a shared understanding of heritage’s “transcendent value,” fostering public emotional connection and conservation motivation, while providing guiding principles for heritage preservation and management. Simultaneously, heritage itself serves as a universal language for cross-cultural exchange, allowing people to intuitively appreciate its charm even without historical context. Moreover, aesthetic value endows heritage with spiritual symbolism and cultural identity, making it a source of social cohesion. Thus, the aesthetic value of heritage does not seek to create differences but to pursue consensus.

Although difficult to quantify, it can be transformed into a “semi-quantitative” reference tool through methods like expert scoring and public perception studies. However, the core significance of aesthetic value lies not in its numerical measurement, but in revealing the unique beauty and irreplaceable cultural significance that make heritage important [

14]. This is key to understanding heritage’s aesthetic value. It can be said that “heritage aesthetics” is the cornerstone of cultural heritage’s creation of social value, as cultural heritage can bring aesthetic pleasure, thereby generating associated emotional consumption [

15]. This is the concrete manifestation of cultural heritage’s aesthetic value.

Beyond generating economic value, heritage aesthetics fosters cohesion through its aesthetic significance—a quality inherent to heritage’s distinctiveness [

16]. From an artistic perspective, diverse aesthetic styles emerge from distinct cultural contexts shaped by different ethnic groups or cross-cultural exchanges. For instance, the Baroque style originated from the secular aesthetic of Italy between the late 16th and early 18th centuries, while Gothic style emerged from the theological culture of France’s Île-de-France region in the 12th century. As these styles spread to other countries and regions worldwide, they adapted to local historical contexts, forming distinctive aesthetic characteristics that became imprinted on heritage sites—particularly heritage architecture.

In turn, these heritage buildings collectively bear witness to the specific histories of different nations or peoples, serving as repositories of collective memory. Take St. Vitus Cathedral in the Czech Republic, for example. It reflects the nation-state’s history from the era of Charles IV of the Holy Roman Empire to the Czechoslovak Republic of the 1920s. Incorporating diverse artistic styles such as Gothic and Baroque, it mirrors the transformations of the Czech nation and state across different historical periods and is regarded as a cultural symbol of both the nation and the people. The cohesion of the nation and people associated with its aesthetic value is undeniable. Within the framework of (national) narratives and collective memory, aesthetic experience constitutes a crucial component. Over extended periods of production, daily life, religion, ritual, and artistic creation, a people develops unique aesthetic sensibilities and ideals. These experiences shape the formal styles of cultural heritage—such as the “unity of heaven and humanity” in Chinese gardens or the pursuit of “harmonious proportions” in Greek sculpture. As the genetic code of cultural heritage, aesthetic experience holds a pivotal position. Cultural heritage possesses ethnic characteristics precisely because it embodies the aesthetic experiences of specific peoples. These experiences are encoded in the spatial layout, ornamentation, colors, materials, and forms of heritage sites. Examples include the Yamato people’s preference for “dry landscape” gardens and the “wabi-sabi” aesthetic in Japan, or the Chinese preference for the color yellow, symbolizing the earth. Shared aesthetic experiences foster a sense of familiarity and belonging among community members when encountering heritage. Simultaneously, the diversity of aesthetic experiences across cultures enables comparative analysis, transforming cultural heritage into a medium for cross-cultural exchange. The willingness to protect heritage often stems from resonance and emotional connection rooted in shared aesthetic experiences. Without aesthetic appreciation, heritage risks becoming mere “ruins” or “antiquities.”

As demonstrated above, from the perspective of heritage communication studies, (ethnic) national narratives, collective memory, and aesthetic experiences collectively form the foundation for understanding heritage aesthetics. Industrial heritage largely aligns with the general characteristics of heritage aesthetics, yet it also possesses its own distinct features.

4. New Functions: The Foundation of Industrial Heritage Aesthetics

To begin, it is necessary to clarify the concept of industrial heritage. Owing to conceptual differences, the term is defined in varying ways across China, the United States, Europe, and Japan. In this study, industrial heritage refers specifically to industrial spaces that have ceased their productive functions and have been reconfigured through processes of adaptive reuse. By this definition, financial heritage (e.g., bank buildings), pre-industrial craft heritage (e.g., ancient breweries), or industrial facilities that remain in active production (e.g., the Steinway Piano Workshop in New York) fall outside the scope of analysis.

Prior to transformation, industrial heritage generally exists in the form of ruins. As modern ruins, however, industrial remains lack the aesthetic resonance typically associated with classical ruins. Unlike Eastern steles, cave Buddha statues, or the temples of ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome—where desolation signifies the distant passage of time and thus invites historical reflection—abandoned factories, disused mine shafts, or derelict water towers seldom evoke comparable appreciation. Classical ruin aesthetics rest upon temporal distance and historical sublimity; in contrast, industrial ruins are often too recent, their dilapidation stemming less from the erosion of centuries than from the intensive exploitation of space and resources inherent in modern industrial production. Continuous high-temperature machinery operations may damage factory floors and walls within decades, while sustained mineral extraction can transform verdant forests into barren pits in a remarkably short span. This mode of ruin is distinct from the gradual transformations wrought by time.

Although one may argue that industrial ruins afford a form of “ruin aesthetics,” [

17] such experiences rarely resonate with broad audiences. In most cases, the aesthetic significance of industrial heritage emerges only through its transformation. Once repurposed—whether into commercial streets, residential communities, cultural facilities, or landscape parks—industrial heritage acquires new value as an aesthetic object. With rare exceptions (such as ruins generated by war or nuclear disasters), unrenovated industrial remnants cannot compare to iconic sites such as Pompeii or the Acropolis in their aesthetic appeal. For instance, before its conversion into a park, the Longlingshan Mine in Wuhan was regarded as a desolate and unsafe periphery of the city, its barren landscape far removed from aesthetic appreciation.

The crucial point, therefore, is that the aesthetic value of industrial heritage resides not in static preservation but in processes of revitalization [

18] (pp. 6–16). Unlike many other forms of cultural heritage, industrial heritage is inherently tied to reuse; its conservation is inseparable from the generation of new functions. This principle is not unique to China but applies globally. Thus, the aesthetics of industrial heritage are largely constructed upon its adaptive functions.

These new functions operate on two levels. First is the functional dimension itself: when industrial spaces are repurposed as commercial, cultural, landscape, or new industrial facilities, they derive aesthetic value from their utility. Consider the case of the Hongkou Slaughterhouse in Shanghai. Originally built by the Shanghai Municipal Council during the concession era, the facility later served as a meat-processing plant and was subsequently converted into a cold-storage warehouse—uses that generated little aesthetic or cultural interest. In recent years, however, it has been redeveloped as the “Old Mill 1935” cultural and creative park. This transformation, aligned with the creation of cafes, bookstores, restaurants, and other urban amenities, has turned the site into a popular destination for young visitors and a celebrated node of industrial heritage in Shanghai. Its widespread recognition, including frequent appearances on social media, demonstrates how aesthetic value in industrial heritage is closely linked to processes of renovation and the introduction of new urban functions.

The aesthetic landscape generated through the transformation of industrial heritage must also be mentioned. In their pre-renovation state, most industrial heritage sites are rarely perceived as aesthetically valuable by the general public, except perhaps by specialists. Years of intensive use often leave such structures severely dilapidated, and in some cases structurally unsafe. Yet, once renovated, they may reveal historically or environmentally significant landscapes with considerable aesthetic appeal. In some instances, the juxtaposition of heritage buildings with newly constructed urban environments produces a striking visual contrast, further enhancing their aesthetic significance.

The case of the Jinghan Railway Jiang’an Station in Wuhan’s Jiang’an District is illustrative. Originally a modest single-story brick station built in the 1910s–1920s, it represented a common form of early railway industrial architecture. Following the abandonment of the line, however, the station was left in disrepair and eventually became enveloped within a residential neighborhood, stripped of aesthetic or functional value. In 2022, during an urban renewal project, the site was redeveloped into a high-end residential and commercial district. As the only surviving historical structure in the area, the station was restored and repurposed as a public space, harmoniously integrated with the newly erected large-scale buildings. This interplay of preservation and modernity created an urban landscape that exemplifies the aesthetic potential of adaptive reuse.

As elements of the urban fabric, industrial heritage sites provide the foundation upon which new functions and associated aesthetics are constructed. A site redeveloped into a shopping mall must embody a fashionable and contemporary design; a new industrial park prioritizes openness and shared spaces; a community-oriented facility requires adaptability to residents’ daily needs; and a park must cultivate an atmosphere of tranquility and natural beauty.

From the perspective of the theory of scene, any artificially constructed environment constitutes a “scene,” and those imbued with aesthetic value represent higher-order scenes—whether art galleries adorned with paintings, luxury hotel lobbies, serene parks, elegant cafés, bustling shopping streets, or solemn churches [

19]. These spaces acquire aesthetic significance through their specific functions: art exchange, accommodation, leisure, consumption, or worship. Industrial heritage, therefore, only becomes aesthetically significant once it is transformed to perform new functions within the urban landscape.

A distinctive dimension of the Chinese experience lies in the legacy of the post-1949 system of “factory managing community,” which gave rise to numerous factory-based company towns embedded within cities [

20,

21]. When many factories went bankrupt, production ceased, but residential populations often remained, especially after the privatization of worker housing during the 1990s. Consequently, numerous industrial heritage sites became inseparable from surrounding communities. Under the momentum of contemporary urban renewal, these sites, once renovated, not only function as community spaces but also generate new forms of aesthetic value.

The NICE2035 “Future Living Street” on Siping Road in Shanghai provides an instructive example. Originally constructed as one of the city’s first workers’ dormitory complexes after 1949, the neighborhood deteriorated over time, and associated production-related buildings such as halls and warehouses fell into obsolescence. Beginning in 2017, a Tongji University research team led the area’s redevelopment, transforming these structures into shared kitchens, community service centers, and public spaces. The renovations preserved the architectural character of the site while incorporating industrial, Nordic, and minimalist American design elements, producing a renewed urban landscape that has attracted wide attention on social media.

This neighborhood employs light-oriented landscape design to articulate a distinctive aesthetic rooted in industrial heritage. The spatial configuration features projectors that illuminate the ground with poems composed by local workers, most of which engage with themes of industrial labor and communal identity. By night, these installations coalesce into a “Poetry on the Road” landscape (

Figure 2), offering a singular visual articulation of industrial aesthetics. This case, therefore, further demonstrates that the aesthetic value of industrial heritage is constituted through the adaptive reconfiguration of its functions within an evolving urban milieu.

5. The Structural Composition of the Aesthetic Value of Industrial Heritage

Any object of aesthetic appreciation possesses its own internal aesthetic system, and industrial heritage, as a form of cultural heritage, is no exception. In the general context of cultural heritage, historical authenticity is often regarded as the cornerstone of aesthetic value [

22] (pp. 69–88). Yet, as previously argued, the foundational aesthetic dimension of industrial heritage lies not in its age or symbolic authenticity but in its functionality. This is not to deny the existence of historical authenticity within industrial heritage; rather, its presence is manifested in the patina of time—the material and technological traces accumulated through industrial use. These traces constitute a distinctive element in the aesthetic system of industrial heritage.

5.1. Technological-Historical Aesthetic Value

Although the “traces of time” in industrial heritage are genuine, they differ from those of traditional cultural heritage. Whereas temples, palaces, or monuments often embody centuries of symbolic and cultural accumulation, most industrial sites bear marks of a shorter duration, defined primarily by phases of industrial production. Consequently, these traces may lack the kind of immediate emotional resonance that captivates the general public in encounters with more conventional heritage. Nonetheless, from the standpoint of technological history, they retain significant aesthetic value and therefore deserve careful preservation in processes of renovation and adaptive reuse.

The technical aesthetic value of industrial heritage refers to the intellectual and sensory appreciation derived from the functional rationality, engineering ingenuity, and innovative spirit that industrial sites embody [

23] (pp. 535–548). This dimension of value emphasizes not simply the “beauty of results,” but also the “beauty of processes and methods of realization.” In other words, the aesthetic response stems from admiration for how problems were solved, how production goals were met, and how technological breakthroughs were achieved. It represents a form of rational beauty—a power and elegance rooted in logic, material authenticity, and innovation—rather than decorative embellishment.

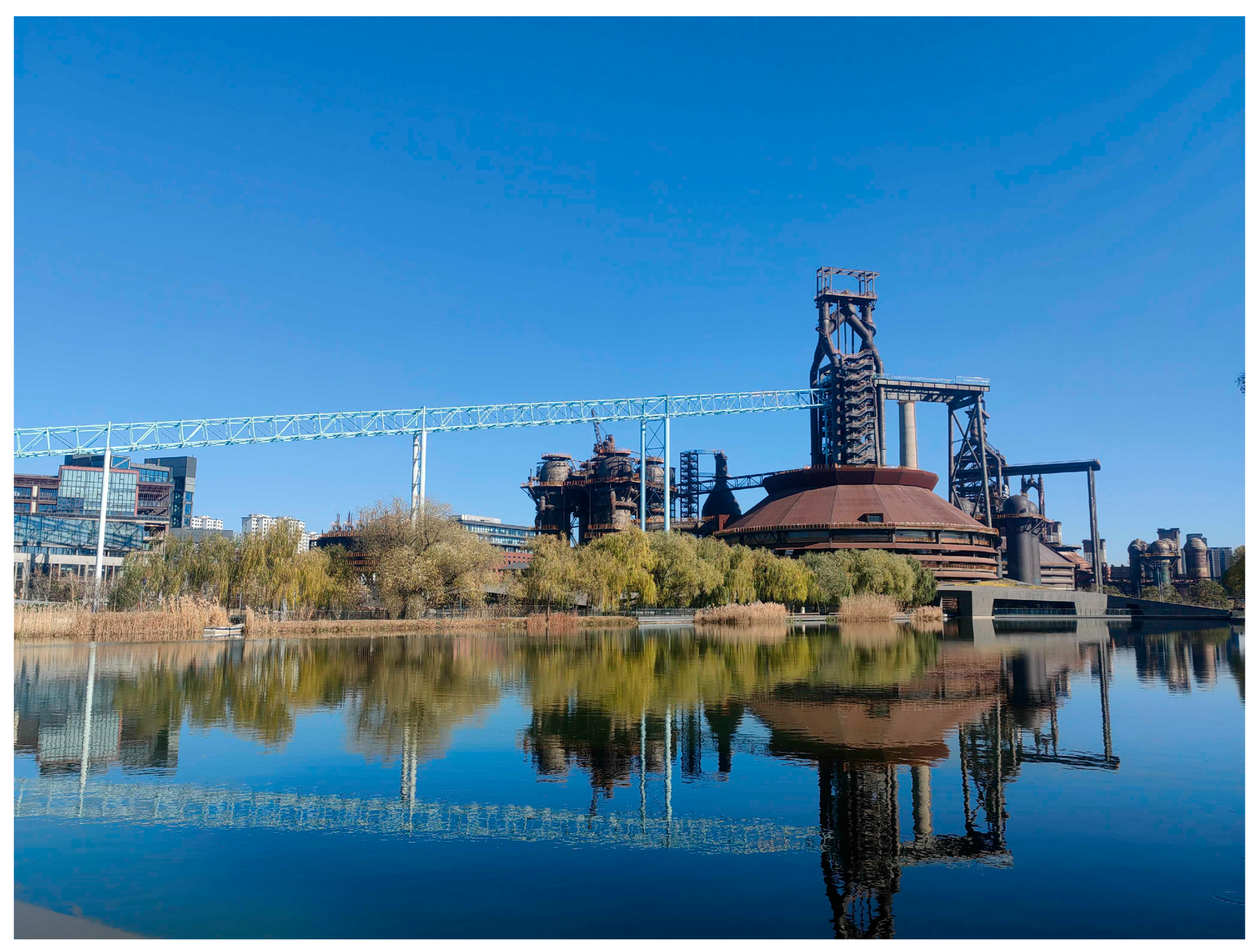

The redevelopment of Beijing’s Shougang Park exemplifies this aesthetic dimension. Once a major steel production site, the complex gained global recognition when facilities such as the power plant, cooling towers, and oxygen plants were reconfigured into the spectacular ski jump venue for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics. The project attracted worldwide media attention and was hailed as a “miracle of sports venue construction” (

Figure 3). While the new aesthetic impact is inseparable from its refunctionalization, the preserved industrial infrastructure itself reveals the strength and beauty of metallurgical technology, serving simultaneously as a historical testimony to China’s heavy-industrial past and as a symbol of the country’s transition to a new model of industrialization.

In this sense, the “traces of time” embodied in industrial heritage are not simply residues of wear, pollution, or obsolescence. Instead, they represent the material imprints of successive technological paradigms within specific historical contexts: the steam-powered textile and milling industries of the First Industrial Revolution, the coal, steel, and electricity complexes of the Second, and the electronics and information technologies of the Third. The very formation of industrial heritage emerges from the phasing out of such technologies, and the material evidence they leave behind is precisely what gives these sites their enduring value. These elements should therefore be prioritized in preservation and restoration, even as new functions are introduced.

This principle is underscored in the National Industrial Heritage Protection Regulations issued by China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The policy explicitly emphasizes the preservation of technological-historical value, particularly in sites of foundational significance to China’s industrialization—such as the first power plant, the first Yangtze River Bridge, or the first railway. The historical traces embedded in these sites are not incidental marks of decay but enduring imprints of the industrialization process, and their conservation through restoration to original condition endows them with profound aesthetic significance.

5.2. Landscape Aesthetic Value

All cultural heritage possesses a landscape aesthetic value, which is often grounded in the historical solidity and spatial integrity of the buildings themselves [

14]. Iconic examples include the Uffizi Palace in Florence, Italy, the Forbidden City in Beijing, China, and the Tomb of Tutankhamun in Thebes, Egypt, each of which constitutes a historical landscape of exceptional aesthetic significance.

As a subset of cultural heritage, industrial heritage similarly embodies landscape aesthetic value, though—consistent with earlier arguments—this value is realized primarily after renovation. In other words, industrial heritage generally becomes an appreciable landscape only through adaptive reuse. The landscape aesthetic value of industrial heritage can be understood through two interrelated dimensions.

First, the aesthetic value inherent in the heritage itself as a landscape. This includes architectural styles with distinctive historical or cultural significance—such as Bauhaus, Art Deco, and Neoclassical structures—which, once restored, stand in marked contrast to contemporary architectural forms. In addition, industrial heritage shaped by natural landscapes—such as canals, mines, or quarries—can, following human intervention and careful renovation, give rise to landscape forms that transcend the aesthetic qualities of purely natural settings.

For instance, the Shanghai Sheshan InterContinental Hotel occupies the site of a former mine in Songjiang, Shanghai. After nearly a century of extraction, the landscape had become rugged, with severe soil erosion. In 2013, the site was transformed into a high-end hotel. Ecological restoration and soil conservation measures reshaped the quarry terrain, providing the foundation for landscaped outdoor areas such as dining terraces, and creating a natural environment integrated with the hotel that exemplifies the aesthetic potential of post-industrial landscapes.

Second, the aesthetic value derived from the new functions introduced to the heritage site. As previously noted, industrial heritage is frequently repurposed into commercial, cultural, or recreational spaces. Such interventions enhance the spatial and visual qualities of the site, generating new landscape experiences. The office building of the Tianjin Machine Tool Factory Archives Office illustrates this point. Originally a simple single-story adaptation of Soviet-style architecture, the building was renovated as a Starbucks café, retaining its industrial character while taking advantage of preexisting fountains, open layouts, and abundant natural light. The transformed space now functions as a notable urban landscape within Tianjin, demonstrating how adaptive reuse can amplify both functional and aesthetic value.

These examples highlight that the landscape aesthetic value of industrial heritage is inseparable from the renovation process and the new functions it enables. Preservation alone is insufficient; the aesthetic significance emerges through the synergistic integration of historical form, environmental context, and contemporary utility.

5.3. Recognition of Aesthetic Value

Industrialization has been a primary driver of human modernization and urbanization, giving rise to industrial culture as a central component of modern civilization alongside agrarian culture [

24]. In China—a country with a long-standing agricultural tradition—industrialization has assumed particular historical and cultural significance. Many Chinese cities, including Huangshi in Hubei, Daqing in Heilongjiang, Jiuquan in Gansu, Panzhihua in Sichuan, Lengshuijiang in Hunan, Duyun in Guizhou, Baiyun Ebo in Inner Mongolia, and Karamay in Xinjiang, were developed as industrial cities during the Mao Zedong era, analogous in planning and function to Magnitogorsk in Russia. Prior to their industrial designation, many of these sites were economically underdeveloped or even uninhabited.

Over more than seventy years of industrial development, these cities have generated vast and relatively complete systems of industrial heritage, the scale of which remains unparalleled internationally. In addition, the Chinese cultural context—characterized by a strong attachment to the land—topophilia [

25]—amplifies the aesthetic resonance of industrial heritage. This attachment is not contingent upon engagement in agriculture; it persists among populations within industrial company towns, where the built environment and daily life are intertwined with industrial functions.

A major factor is the collective living model of Chinese company towns—“factory managing community”. Children born in such towns—where both parents are factory workers—often complete their education from kindergarten through high school, and in some cases through technical colleges operated by the factory. Even if most eventually leave, the company town remains a formative environment shaping their early experiences and worldview. It is estimated that approximately 30 million Chinese individuals belong to this cohort of “sons and daughters of the factories.” Following the reform and privatization of state-owned enterprises during the Jiang Zemin era, production of new cohorts ceased. Yet the former residents maintain enduring emotional ties to the towns where they grew up, rendering these sites spiritual homes.

The emotional attachment extends beyond individuals to the factory buildings themselves. Take Huangshi City as an example: founded as China’s first industrial special zone, the city had a population of 220,000 in 1960, of which 195,000 were workers and their families. Even schools, hospitals, and other civic infrastructure not directly affiliated with factories were planned to support factory life [

26] (80–85). Research demonstrates that residents of traditional industrial cities in China maintain a profound emotional connection to industrial buildings, especially following industrial restructuring.

Consequently, industrial heritage embodies an identity-based aesthetic, closely tied to local culture and collective memory. In many Chinese industrial cities, industrial culture has become an intrinsic component of urban identity, and industrial heritage exerts a culturally resonant aesthetic influence upon residents [

27]. The core of this aesthetic lies in shared memory, with industrial heritage functioning as a site of collective remembrance. Unlike most traditional cultural heritage, industrial heritage often retains emotional connections with living populations due to its relatively recent history.

For example, Hanggang Park in Hangzhou, transformed from the Hangzhou Iron and Steel Plant, exemplifies this principle. Nearly 10,000 retired employees or family members continue to reside near the park, actively participating in cultural activities and gatherings there (

Figure 4). Such cases are common across China’s industrial cities, illustrating that the aesthetic value of industrial heritage is not only visual or functional but also socially and emotionally constructed through ongoing interactions with communities.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The aesthetic value of industrial heritage may appear complex, yet it is grounded in a simple logic: why do we appreciate industrial heritage? In the consumer-oriented era of industrialization, industrial heritage projects function not only as cultural sites but also as commodities. They gain popularity and social acceptance—sometimes even becoming consumer phenomena—because they align with contemporary aesthetic sensibilities and lifestyle preferences.

When considering cultural heritage as a commodity, a common misconception arises: that consumers are primarily purchasing historical significance, or that aesthetic appreciation is inherently dependent on historical value. From the perspective of a market economy, however, historical value is often overestimated. In practical terms, when selecting an industrial heritage site for use as a design studio, office, or commercial facility, factors such as practicality, rental conditions, and visual appeal frequently outweigh historical considerations.

Heritage preservation is also inherently a process of political and policy intervention, particularly in the context of urban renewal and sustainable development [

28]. Industrial heritage is often conceptualized as an urban resource, whose aesthetic value is inseparable from its functional potential. In other words, the recognition of industrial heritage aesthetic value is as much about its capacity to fulfill contemporary urban functions as it is about historical or visual significance.

Among the components of industrial heritage aesthetics, landscape and identity-based values are particularly salient. While traditional cultural heritage also possesses landscape value, it is largely inherent and self-evident. Sites such as the Parthenon, Luxor Temple, or the Great Wall of China require minimal intervention to convey aesthetic significance. In contrast, most industrial heritage cannot become an aesthetically appreciable landscape without comprehensive renovation. Thus, the landscape aesthetic value of industrial heritage emerges from the integration of contemporary utility and historical context.

Similarly, identity-based aesthetic value is not unique to industrial heritage. Benedict Anderson emphasizes that nations are “imagined communities,” [

29] (pp. 282–288) and that national cultural symbols—such as the Great Wall or the Egyptian pyramids—play a central role in shaping collective identity. However, the recognition of industrial heritage tends to be group-specific, resonating most strongly with individuals who have lived or worked in industrial environments, rather than with the broader national population. Of course, the presence or absence of personal resonance does not determine whether industrial heritage possesses aesthetic value, nor does it alone dictate its commodification. Even without evoking direct resonance, an observer can apprehend its intrinsic aesthetic qualities, thereby enabling its recognition and circulation as a commodity.

In conclusion, the aesthetic value of industrial heritage shares commonalities with broader cultural heritage, including historical, landscape, and identity-based dimensions, while simultaneously possessing unique characteristics derived from functionality, contemporary reuse, and social embeddedness. Industrial heritage should therefore be understood as an integral component of the cultural heritage aesthetic system, rather than as an isolated or wholly distinct category. Recognizing this interconnectedness is essential for a comprehensive evaluation of its aesthetic significance.

Of course, the discussion thus far has focused solely on China. In reality, were space to allow, a comparative examination of the aesthetic value of industrial heritage in other Global South countries—such as India, Malaysia, and Peru—would be illuminating. These differences may be subtle, yet approached through a postcolonial lens, the insights they yield could be unexpectedly revealing. Likewise, the similarities and divergences between China and (former) socialist countries—such as Uzbekistan, Hungary, Russia, Cuba, and North Korea—merit careful consideration. This manuscript, therefore, represents only a point of departure. I hope that more voices will join the conversation on the aesthetic value of industrial heritage, a topic that clearly extends beyond China and beyond heritage itself. In the era of globalization, it should be approached as a stimulating cultural issue.