Strategies for Increasing Methane Removal in Methanotroph Stirred-Tank Reactors for the Production of Ectoine

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Methane Background

1.2. Methanotroph Background

1.3. Ectoine

1.4. Mass Transfer of CH4

2. Methods

2.1. Culture and Media

2.2. Inoculation Preparation

2.3. Reactor Setup

2.4. Tested Factors

2.4.1. Temperature

2.4.2. Sparger Pore Size

2.4.3. Gas Input

2.5. Downstream Processing

2.6. Analytical

2.6.1. Cell Density

2.6.2. CH4 Concentration

2.6.3. Ectoine Quantification

2.7. Calculation and Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Calculation

2.7.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

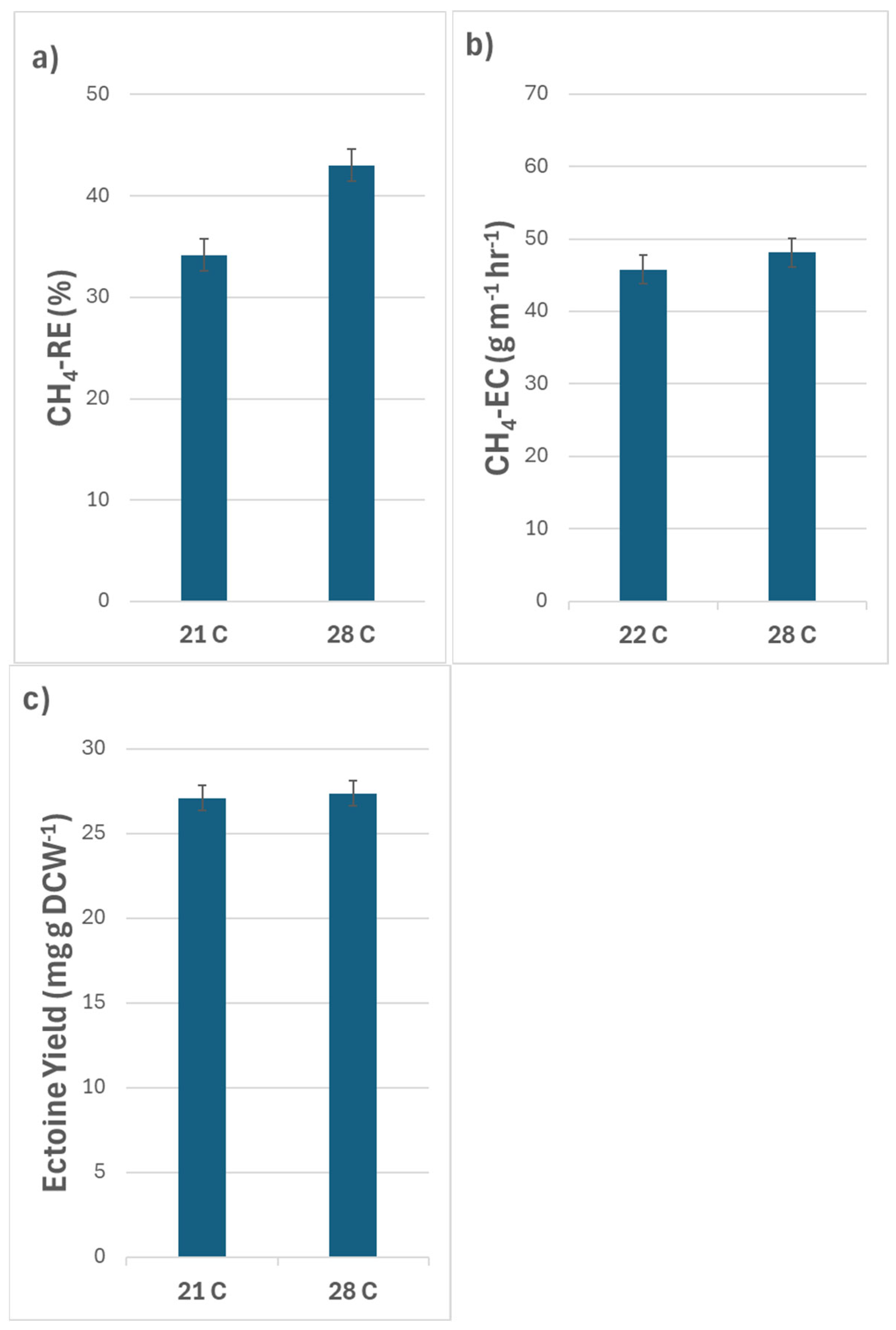

3.1. Effects of Temperature

3.2. Effects of Sparger Pore Size

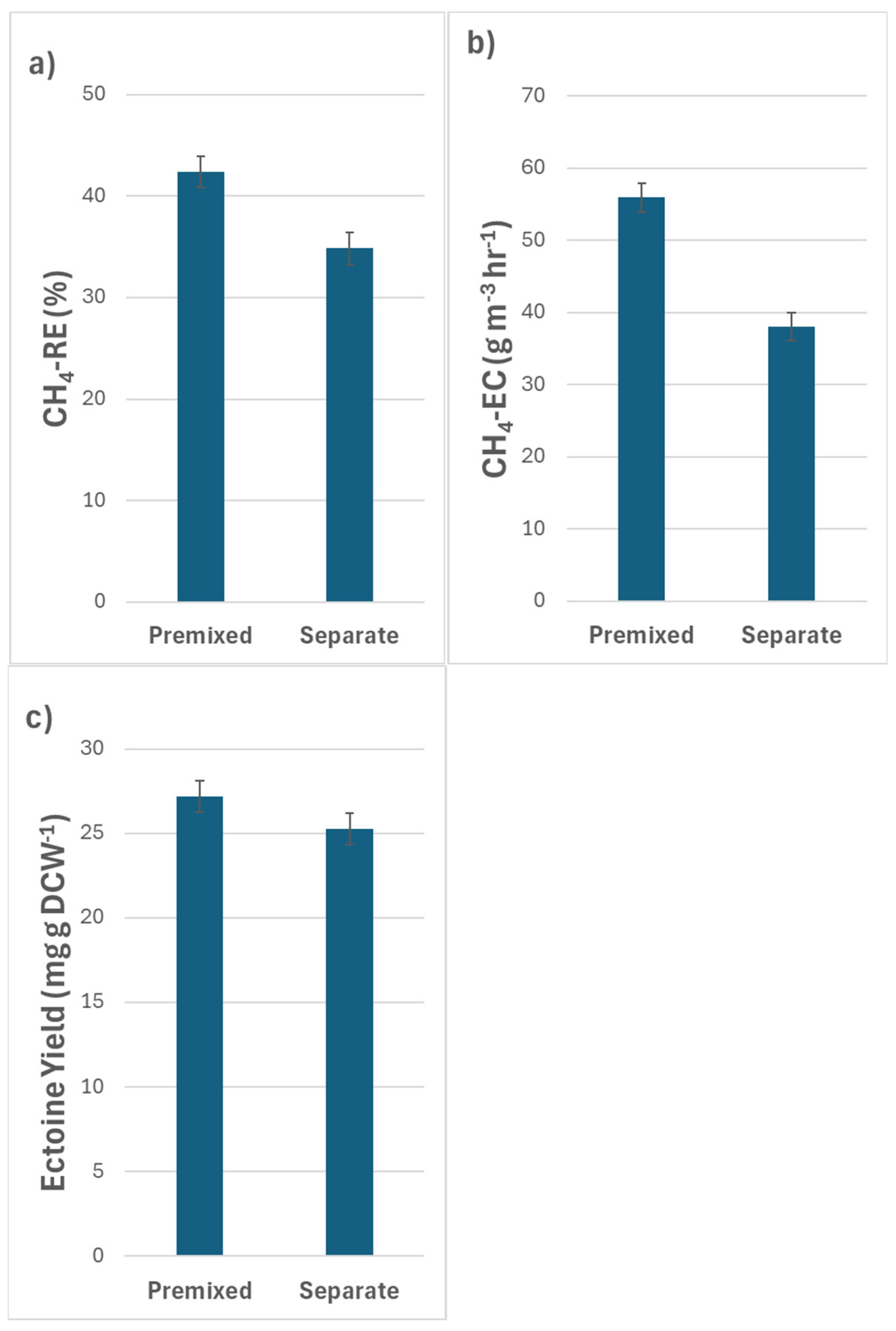

3.3. Effects of Gas Input Method

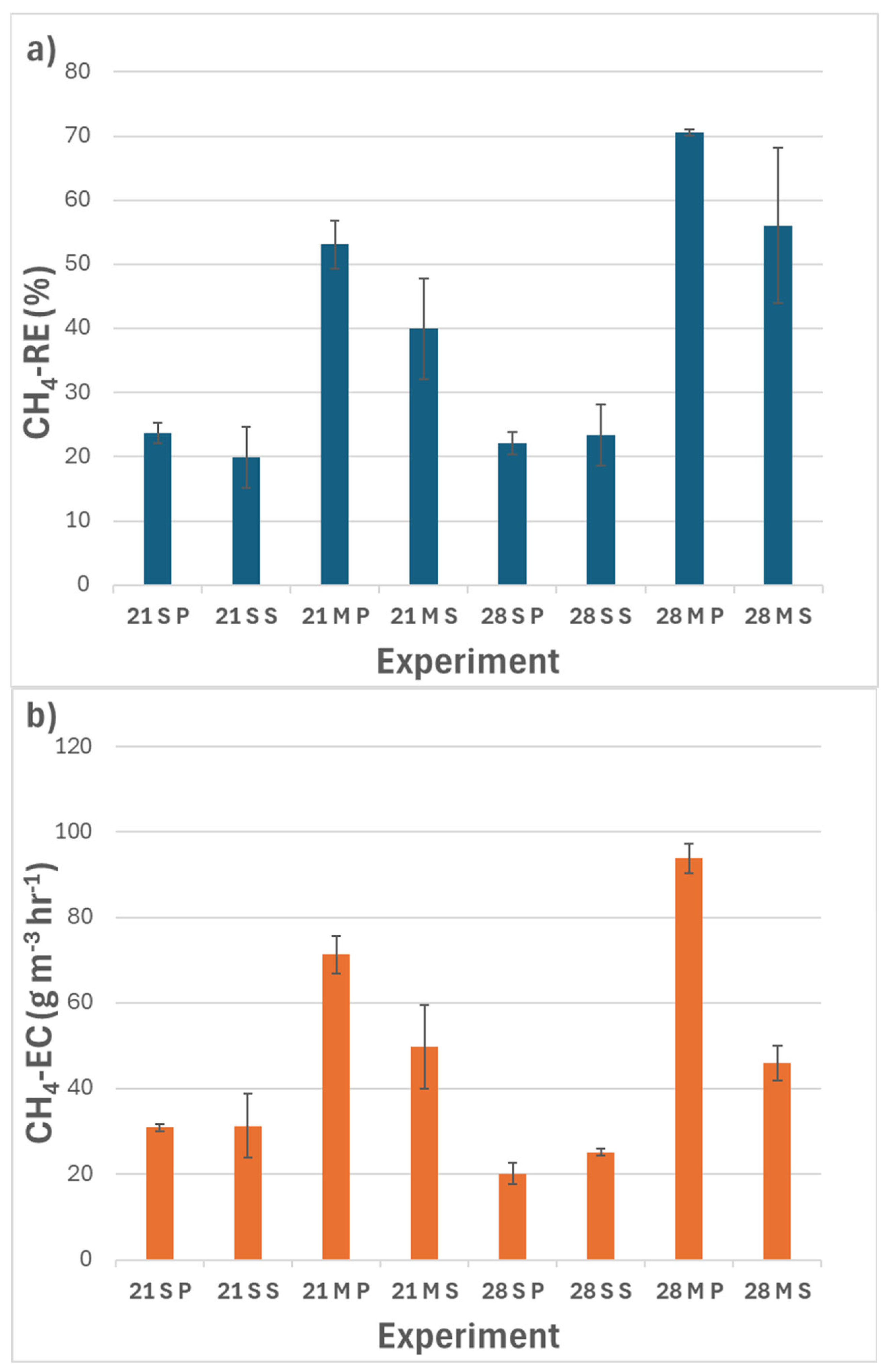

3.4. Optimal Set-Up

3.5. Interactions Between Factors

3.6. Tangential Flow Filtration

3.7. Reactor Productivity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Importance of Methane. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/gmi/importance-methane (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Song, C.; Zhu, J.-J.; Willis, J.L.; Moore, D.P.; Zondlo, M.A.; Ren, Z.J. Methane Emissions from Municipal Wastewater Collection and Treatment Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2248–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, M.; Lou, Z.; He, H.; Guo, Y.; Pi, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, K.; Fei, X. Methane Emissions from Landfills Differentially Underestimated Worldwide. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ge, X.; Wan, C.; Yu, F.; Li, Y. Progress and Perspectives in Converting Biogas to Transportation Fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, P.J.; Xie, S.; Clarke, W.P. Methane as a Resource: Can the Methanotrophs Add Value? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4001–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrell, J.C.; Gilbert, B.; McDonald, I.R. Molecular Biology and Regulation of Methane Monooxygenase. Arch. Microbiol. 2000, 173, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, P.J.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.; Silverman, J.; Clarke, W.P. A Methanotroph-Based Biorefinery: Potential Scenarios for Generating Multiple Products from a Single Fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khmelenina, V.N. Isolation and Characterization of Halotolerant Alkaliphilic Methanotrophic Bacteria from Tuva Soda Lakes. Curr. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera, S.; Lebrero, R.; Sadornil, L.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Valorization of CH 4 Emissions into High-Added-Value Products: Assessing the Production of Ectoine Coupled with CH 4 Abatement. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khmelenina, V.N.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Sakharovsky, V.G.; Suzina, N.E.; Trotsenko, Y.A.; Gottschalk, G. Osmoadaptation in Halophilic and Alkaliphilic Methanotrophs. Arch. Microbiol. 1999, 172, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantera, S.; Estrada, J.M.; Lebrero, R.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Comparative Performance Evaluation of Conventional and Two-Phase Hydrophobic Stirred Tank Reactors for Methane Abatement: Mass Transfer and Biological Considerations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, J.M.; Salvador, M.; Argandoña, M.; Bernal, V.; Reina-Bueno, M.; Csonka, L.N.; Iborra, J.L.; Vargas, C.; Nieto, J.J.; Cánovas, M. Ectoines in Cell Stress Protection: Uses and Biotechnological Production. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Martínez, A.A.; Marcos-Rodrigo, E.; Bordel, S.; Marín, D.; Herrero-Lobo, R.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Elucidating the Key Environmental Parameters during the Production of Ectoines from Biogas by Mixed Methanotrophic Consortia. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, I.; Jindo, Y.; Nagaoka, M. Microscopic Understanding of Preferential Exclusion of Compatible Solute Ectoine: Direct Interaction and Hydration Alteration. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 10231–10238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröter, M.-A.; Meyer, S.; Hahn, M.B.; Solomun, T.; Sturm, H.; Kunte, H.J. Ectoine Protects DNA from Damage by Ionizing Radiation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinski, E.A.; Pfeiffer, H.-P.; Trüper, H.G. 1,4,5,6-Tetrahydro-2-Methyl-4-Pyrimidinecarboxylic Acid. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985, 149, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarusintanakorn, S.; Mastrobattista, E.; Yamabhai, M. Ectoine Enhances Recombinant Antibody Production in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells by Promoting Cell Cycle Arrest. New Biotechnol. 2024, 83, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widderich, N.; Höppner, A.; Pittelkow, M.; Heider, J.; Smits, S.H.J.; Bremer, E. Biochemical Properties of Ectoine Hydroxylases from Extremophiles and Their Wider Taxonomic Distribution among Microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccai, G.; Bagyan, I.; Combet, J.; Cuello, G.J.; Demé, B.; Fichou, Y.; Gallat, F.-X.; Galvan Josa, V.M.; von Gronau, S.; Haertlein, M.; et al. Neutrons Describe Ectoine Effects on Water H-Bonding and Hydration around a Soluble Protein and a Cell Membrane. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunte, H.; Lentzen, G.; Galinski, E. Industrial Production of the Cell Protectant Ectoine: Protection Mechanisms, Processes, and Products. Curr. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, T.; Galinski, E.A. Bacterial Milking: A Novel Bioprocess for Production of Compatible Solutes. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1998, 57, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera, S.; Lebrero, R.; Rodríguez, S.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Ectoine Bio-Milking in Methanotrophs: A Step Further towards Methane-Based Bio-Refineries into High Added-Value Products. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 328, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Rodero, M.R.; Carmona-Martínez, A.A.; Martínez-Fraile, C.; Herrero-Lobo, R.; Rodríguez, E.; García-Encina, P.A.; Peña, M.; Muñoz, R. Ectoines Production from Biogas in Pilot Bubble Column Bioreactors and Their Subsequent Extraction via Bio-Milking. Water Res. 2023, 245, 120665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.K.; Ivone, R.; Shen, J.; Meenach, S.A. A Comparison of Centrifugation and Tangential Flow Filtration for Nanoparticle Purification: A Case Study on Acetalated Dextran Nanoparticles. Particuology 2020, 50, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ramsay, J.A.; Ramsay, B.A. On-Line Estimation of Dissolved Methane Concentration during Methanotrophic Fermentations. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 95, 788–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenburg, D.A.; Guinasso, N.L., Jr. Equilibrium Solubilities of Methane, Carbon Monoxide, and Hydrogen in Water and Sea Water. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1979, 24, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yan, L.; Cao, J.; Wang, K.; Luo, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Yu, R.; Pan, B.; Yu, K.; et al. Salinity Significantly Affects Methane Oxidation and Methanotrophic Community in Inner Mongolia Lake Sediments. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1067017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.R.; Rai, R.K.; Green, S.J.; Chetri, J.K. Effect of Temperature on Methane Oxidation and Community Composition in Landfill Cover Soil. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, V.; Moltó, J.L.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Ectoine Production from Biogas in Waste Treatment Facilities: A Techno-Economic and Sensitivity Analysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 17371–17380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Rodero, M.R.; Herrero-Lobo, R.; Pérez, V.; Muñoz, R. Influence of Operational Conditions on the Performance of Biogas Bioconversion into Ectoines in Pilot Bubble Column Bioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 358, 127398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantera, S.; Phandanouvong-Lozano, V.; Pascual, C.; García-Encina, P.A.; Lebrero, R.; Hay, A.; Muñoz, R. A Systematic Comparison of Ectoine Production from Upgraded Biogas Using Methylomicrobium Alcaliphilum and a Mixed Haloalkaliphilic Consortium. Waste Manag. 2020, 102, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Khmelenina, V.; Eshinimaev, B.; Sorokin, D.; Fuse, H.; Lidstrom, M.; Trotsenko, Y. Classification of Halo(Alkali)Philic and Halo(Alkali)Tolerant Methanotrophs Provisionally Assigned to the Genera Methylomicrobium and Methylobacter and Emended Description of the Genus Methylomicrobium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akberdin, I.R.; Thompson, M.; Hamilton, R.; Desai, N.; Alexander, D.; Henard, C.A.; Guarnieri, M.T.; Kalyuzhnaya, M.G. Methane Utilization in Methylomicrobium Alcaliphilum 20ZR: A Systems Approach. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.; Ha, S.; Kim, H.S.; Han, J.H.; Kim, H.; Yeon, Y.J.; Na, J.G.; Lee, J. Stimulation of Cell Growth by Addition of Tungsten in Batch Culture of a Methanotrophic Bacterium, Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z on Methane and Methanol. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 309, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantera, S.; Lebrero, R.; Rodríguez, E.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Continuous Abatement of Methane Coupled with Ectoine Production by Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z in Stirred Tank Reactors: A Step Further towards Greenhouse Gas Biorefineries. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozova, O.N.; Khmelenina, V.N.; Bocharova, K.A.; Mustakhimov, I.I.; Trotsenko, Y.A. Role of NAD+-Dependent Malate Dehydrogenase in the Metabolism of Methylomicrobium Alcaliphilum 20Z and Methylosinus Trichosporium OB3b. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Firmino, P.I.M.; Pérez, V.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Biogas Valorization via Continuous Polyhydroxybutyrate Production by Methylocystis hirsuta in a Bubble Column Bioreactor. Waste Manag. 2020, 113, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s Law Constants (Version 4.0) for Water as Solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 4399–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Ma, J.; Winter, C.; Bayer, R. Recovery and Purification Process Development for Monoclonal Antibody Production. mAbs 2010, 2, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecular Weight | Melting Point | Solubility | pH Range | pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 142.16 g/mol | 280 °C | 568 g/L (Water) | 5.5–9.6 | 3.14 |

| 10 g/L (MeOH) |

| Experiment | Temperature | Sparger Pore Size | Gas Input Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21SP | 21 | 1 mm | Premixed |

| 21SS | 21 | 1 mm | Separate |

| 21MP | 21 | 0.5 µm | Premixed |

| 21MS | 21 | 0.5 µm | Separate |

| 28SP | 28 | 1 mm | Premixed |

| 28SS | 28 | 1 mm | Separate |

| 28MP | 28 | 0.5 µm | Premixed |

| 28MS | 28 | 0.5 µm | Separate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Storrer, J.; Mazurkiewicz, T.M.; Hancock, B.; Sims, R.C. Strategies for Increasing Methane Removal in Methanotroph Stirred-Tank Reactors for the Production of Ectoine. Bioresour. Bioprod. 2025, 1, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020007

Storrer J, Mazurkiewicz TM, Hancock B, Sims RC. Strategies for Increasing Methane Removal in Methanotroph Stirred-Tank Reactors for the Production of Ectoine. Bioresources and Bioproducts. 2025; 1(2):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020007

Chicago/Turabian StyleStorrer, Jaden, Tansley M. Mazurkiewicz, Bodee Hancock, and Ronald C. Sims. 2025. "Strategies for Increasing Methane Removal in Methanotroph Stirred-Tank Reactors for the Production of Ectoine" Bioresources and Bioproducts 1, no. 2: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020007

APA StyleStorrer, J., Mazurkiewicz, T. M., Hancock, B., & Sims, R. C. (2025). Strategies for Increasing Methane Removal in Methanotroph Stirred-Tank Reactors for the Production of Ectoine. Bioresources and Bioproducts, 1(2), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioresourbioprod1020007