1. Introduction

Facial cosmetic surgery has evolved as a timeless approach to achieving personal aesthetic harmony and addressing perceived physical imperfections. Throughout history, ideas and attitudes concerning facial aesthetic procedures have evolved greatly. Historically, many early facial procedures originated from reconstructive efforts aimed at restoring form and function. Over time, these same principles were adapted to address aesthetic goals, marking the shift from reconstruction to refinement. Distinguishing between reconstructive and cosmetic foundations in each procedure helps illustrate how plastic surgery evolved into the multidisciplinary field it is today. In the modern era, perspectives on plastic surgery continue to evolve, being greatly influenced by cultural, technological, and medical advancements. However, a duality regarding the reasons for pursuing plastic surgeries exists between reconstructive goals and the aim of aesthetic refinement. The reconstructive aspect of plastic surgery emphasizes the restoration of function and physical integrity, whereas aesthetic procedures tend to focus on the enhancement of appearance and self-perception. In this educational narrative review, we provide a comprehensive description of the history of facial aesthetic surgery with the aim of illuminating the relevance of this history for modern-day plastic surgeons. While existing literature has addressed the history of various aesthetic surgical procedures, very few have directly linked historical milestones to the development of modern facial aesthetic techniques and contemporary technologies. This educational review bridges the gap by connecting early innovations with current trends, such as AI, VR, and 3D planning, and highlights how foundational surgical practices continue to inform and contribute to modern aesthetic procedures. Understanding the evolution of aesthetic surgical techniques can deepen clinicians’ understanding of their role within the broader continuum of medical progress and foster a greater appreciation for the diverse needs of their patients.

2. Methods

This work is an educational narrative review. Sources were identified through a targeted search of PubMed, Google Scholar, and major plastic surgery textbooks. There were no time limits in order to capture the full evolution of facial aesthetic surgery, from early reconstructive work to modern techniques. Articles were included if they described the development or cultural relevance of key facial aesthetic procedures. Both Western and non-Western contributions were included to reflect a global perspective. Non–peer-reviewed sources were excluded unless they served as a primary historical reference.

3. Early Beginnings in Facial Aesthetic Surgery

The earliest reconstructive procedures, such as nasal repairs in ancient Egypt, laid the groundwork that centuries later would inform aesthetic techniques in achieving facial harmony. Various reconstructive techniques were used to repair broken noses, such as the incorporation of seeds and bones into the nasal region. The

Edwin Smith Papyrus outlined these early nasal reconstruction efforts, emphasizing anatomical restoration, which served as an early example of aligning physical repair with cultural ideals of identity [

1,

2]. These procedures laid the foundation for future plastic surgical approaches, integrating the ideals of physical restoration with personal identity.

It was not until 600 BCE in India that the surgical pioneer Sushruta Samhita developed innovative procedures that laid the groundwork for modern-day oral maxillofacial procedures. Although his techniques were primarily reconstructive, these methods introduced ideas of symmetry and tissue replacement that have informed more modern aesthetic procedures. Often referred to as the “Father of Plastic Surgery,” Sushruta’s description of nasal reconstruction using a pedicled forehead flap established one of the earliest models of tissue transfer and donor-site planning, concepts that continue to guide reconstructive techniques today [

3,

4]. In the procedures, Sushruta used a leaf to measure the dimension of the nasal defect and then harvested a flap of skin from the cheek to join to the amputated nose. After sheltering the nose with cotton and sesame seeds, he used a hollow tube to keep the nostrils open during the procedure. The practice gradually shifted from using cheek flaps to utilizing forehead flaps [

3,

5].

Between 100 BCE and the 5th century CE, the Romans played a pivotal role in developing methods for augmenting damaged ears and other craniofacial structures. Aulus Cornelius Celsus, the Roman medical writer who authored “De Medicina,” emphasized the importance of cleanliness for wound healing and endorsed the use of antiseptic agents such as vinegar, honey, and rose oil [

6,

7]. Celsus also described various plastic surgery techniques involving the complexity of skin transection and differentiating between clean and infected wounds [

6,

7].

During the Renaissance era, facial and nasal mutilations were an all-too-common result of syphilis, war wounds, and punishment [

8]. One unusual non-surgical technique of the time for hiding these mutilations was wearing a silver prosthetic nose attached to glasses that were tied around the neck [

8]. But innovative surgical procedures were also developed during this time. Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545–1599) was another pioneer of plastic surgery who legitimized nasal reconstruction as a formal surgical discipline and introduced structured flap design that integrated vascular delay and layered closure. Tagliacozzi’s gift to the field of plastic surgery was legitimizing the nasal reconstruction procedure through the use of an upper arm flap (Miller) [

8,

9,

10].

However, it was not until the 19th century that the term “plastic surgery” was introduced into colloquial medical speech with the publication of the text “

Rhinoplastik” by the German surgeon Karl Ferdinand von Graefe [

11,

12]. Von Graefe was instrumental in streamlining the practice of using skin flaps from the arm to restore nasal mutilation, otherwise known as the “Italian method” [

8,

12]. It was during this era that reconstructive surgeries began to expand. In 1895 the first breast augmentation was performed; a key event marking the growing integration of reconstructive surgical techniques with aesthetic goals, and signaling the shift toward more cosmetically focused procedures [

13,

14]. These advancements highlight international progression of reconstructive and aesthetic principles, as summarized in

Figure 1.

4. The Challenge of Beauty Doctors

4.1. Context and Origins

In the late 19th century, a controversial societal shift placed increasing emphasis on physical appearance, leading to the emergence of the so-called “beauty doctors.” These practitioners capitalized on the growing demand for aesthetic enhancement but typically lacked formal medical education or training. Operating out of beauty salons, they often performed procedures without standardized protocols or medical oversight. This era represents a critical phase in the evolution of aesthetic surgery, as it blurred the lines between cosmetic procedures and medical care [

15].

4.2. Charles Miller’s Contributions and Innovations

Charles Miller, an early beauty doctor, is well known for his 1907 publication “

The Correction of Featural Imperfections.” This text served as a foundation for various aesthetic procedures, offering a methodical approach to facial modifications including eyelid surgeries, nasolabial fold adjustments, double-chin excisions, and more. By scripting these procedures, Dr. Miller helped delineate the burgeoning field of cosmetic and reconstructive surgery, offering a foundational reference for other practitioners [

16]. However, there were various concerns with Miller’s procedure, including his use of paraffin injections to correct “saddle noses” and facial wrinkles. The use of paraffin can lead to granuloma formation, skin indurations, and inflammation, and Miller’s approach reflected the risks and missteps of early aesthetic procedures, where safety was often overlooked in pursuit of aesthetic appeal [

17]. The complications associated with these early methods highlighted the importance of training for medical professionals and safety regulations, a now well-emphasized and integral component to modern-day aesthetic surgery.

4.3. John H. Woodbury and the Commercialization of Aesthetic Procedures

John H. Woodbury (1851–1909) was a 19th-century self-trained dermatologist and entrepreneur who contributed to the rise and commercialization of cosmetic procedures. Woodbury effectively created an accessible model of cosmetic procedures for the general public. His procedures entailed browlifts, chin reconstructions, rhinoplasties, and other facial procedures that laid the groundwork for the widely expanded techniques used today. His large-scale clinics demonstrated public demand for aesthetic procedures but also highlighted the increasing prevalence of unregulated medical practice, which later influenced more rigorous patient safety standards and the requirement of certification [

18].

4.4. The Role of Advertising in Shaping Public Perceptions of Aesthetic Surgery

Woodbury’s open use of advertisements and before-and-after images was critical for normalizing aesthetic procedures as a means to augment beauty. His approach allowed the public to see aesthetic procedures as a means for “transformation” or improvement of oneself. However, ethical concerns were raised regarding Woodbury’s use of advertisements, which suggested that beautification procedures were a simple, risk-free means of achieving a desirable appearance, basically promoting a false narrative that elective surgical enhancements carry minimal risk. This problem of commodification of beauty-enhancing surgeries with a concomitant downplaying of risk continues to this day, and the expansion of communication tools such as the internet and social media have created a more complex ethical landscape that contemporary clinicians must contend with [

18,

19].

While the Dermatologic Institute helped popularize the concept of aesthetic surgery, it contributed to a field that lacked regulatory oversight. An increasing awareness of the potential dangers associated with unsupervised cosmetic procedures began to emerge with the growth of this practice. Overall, Woodbury’s work stimulated discussion regarding the urgent need for formalized training processes within aesthetic surgery, foreshadowing the strict regulation of modern practices of the field today.

These discussions marked a critical turning point for aesthetic surgery as a developing field. The rise of “beauty doctors” reflected the growing tension between people’s desire for aesthetic change and the responsibilities of medicine. Without proper oversight, patients were often exposed to serious risks, raising an ethical question that still exists today: where do we draw the line between medicine and beauty? Similar issues continue in the modern era with medical tourism and elective procedures. These early controversies pushed the field toward more regulation, standardized training, and accountability. The lessons learned during this time helped shape modern aesthetic surgery and emphasized that safety and professional standards should always guide cosmetic care.

5. Defining Beauty and Its History

Beauty has been a central and enduring element of human culture across civilizations and historical eras. The

Cambridge Dictionary defines beauty as “an attractive quality that gives pleasure to those who experience or think about it, or a person who has this attractive quality” [

20]. However, beauty can be interpreted through a wide range of lenses; philosophical, biopsychological, emotional, aesthetic, and even deeply personal conceptions [

21]. Arriving at a single, comprehensive definition of beauty is difficult, as its meaning varies greatly depending on cultural, historical, and geographical contexts. In ancient Greece, for instance, Plato examined the concept of

Kalon, meaning beauty, and its broader implications for society. In the dialogue

Hippias Major, Socrates and Hippias debate the nature of beauty. Hippias argues that beauty is found in all things considered “good,” relying on what he sees as a universal social consensus [

21]. Socrates, however, challenges this notion throughout the dialogue, ultimately leaving the question unresolved [

22]. These early philosophical discussions underscore that beauty is multifaceted and elusive; there is no single, essential characteristic that universally defines it.

While cultural constructs shape our understanding of beauty, scientists have attempted to identify more objective, measurable components of physical attractiveness. Research suggests that traits such as facial symmetry, averageness, sexual dimorphism, and skin homogeneity all influence perceived attractiveness. Interestingly, “averageness”; how closely a face resembles the population average; may have an even stronger effect [

23]. In one study, facial images that were digitally averaged to represent a population mean were rated as more attractive, with higher attractiveness correlating to a greater number of images used in the averaging process [

24,

25]. Furthermore, extreme beauty has been linked to exaggerated features, such as a more prominent chin in men. These findings suggest that overall facial configuration, rather than isolated features like the eyes or nose, plays a greater role in perceived beauty; possibly because average faces are cognitively easier to process [

23,

24,

25].

Beyond facial structure, body fat distribution also influences perceptions of physical beauty, particularly due to its sexual dimorphism [

23]. In men, traits such as muscularity, low body fat percentage, broad shoulders, and a V-shaped torso with a waist-to-shoulder ratio around 0.6 are often seen as attractive. In contrast, for women, a small waist-to-hip ratio has remained a consistent marker of beauty across cultures and historical periods; even as ideals have evolved [

23,

26]. Skin tone and texture also matter; specifically, skin color homogeneity (evenness in tone and texture) is another predictor of attractiveness [

27].

Ultimately, our perceptions of beauty cannot be reduced to a fixed checklist of traits. Rather, beauty is a dynamic and ever-evolving concept; one that continues to resist simple definition, even for the greatest of philosophers.

6. Modern Principles in Facial Aesthetic Analysis

Various principles can be traced back to ancient times when mathematicians and artists aimed to systematically calculate the metrics of visual concordance. Euclid’s golden ratio, the “divine proportion,” was approximately 1:1.618, describing a mathematical relationship consistently observed in nature, art, and architecture [

28]. Many have argued that this ratio describes a more masculine perspective, while smaller and more balanced facial divisions (e.g., uniform thirds and fifths) are more desirable for a female aesthetic. Building upon this principle, the Roman architect Vitruvius introduced the method of facial trisection, otherwise known as the “rule of thirds”—a popular metric that is used even today in both art and medicine [

29]. Leonardo da Vinci later delved deeper into these paradigms by delineating the “Vitruvian Man,” formulating the ideal facial proportions of vertical fifths [

30].

Facial aesthetics rely upon the three-dimensional topography of the central features of the face—the eyes, nose, cheeks, and lips—and various methods for making objective measurements of these physiological features have been developed [

31]. Cephalometry is an analytic system used to evaluate the morphological shape of craniofacial structures and examine the spatial relationships between skeletal structures [

31]. This method makes it possible to assess the sagittal, vertical, and transverse relationships between both skeletal and soft profiles, which allows for more informed pre-surgical decision-making and increased diagnostic accuracy. More recently, anthropometric methods that evaluate surface topographic measurements have been developed, and these methods are preferable to cephalometric methods for determining ideal facial proportions because they allow deeper analysis of the three-dimensional morphologies of external tissues [

31].

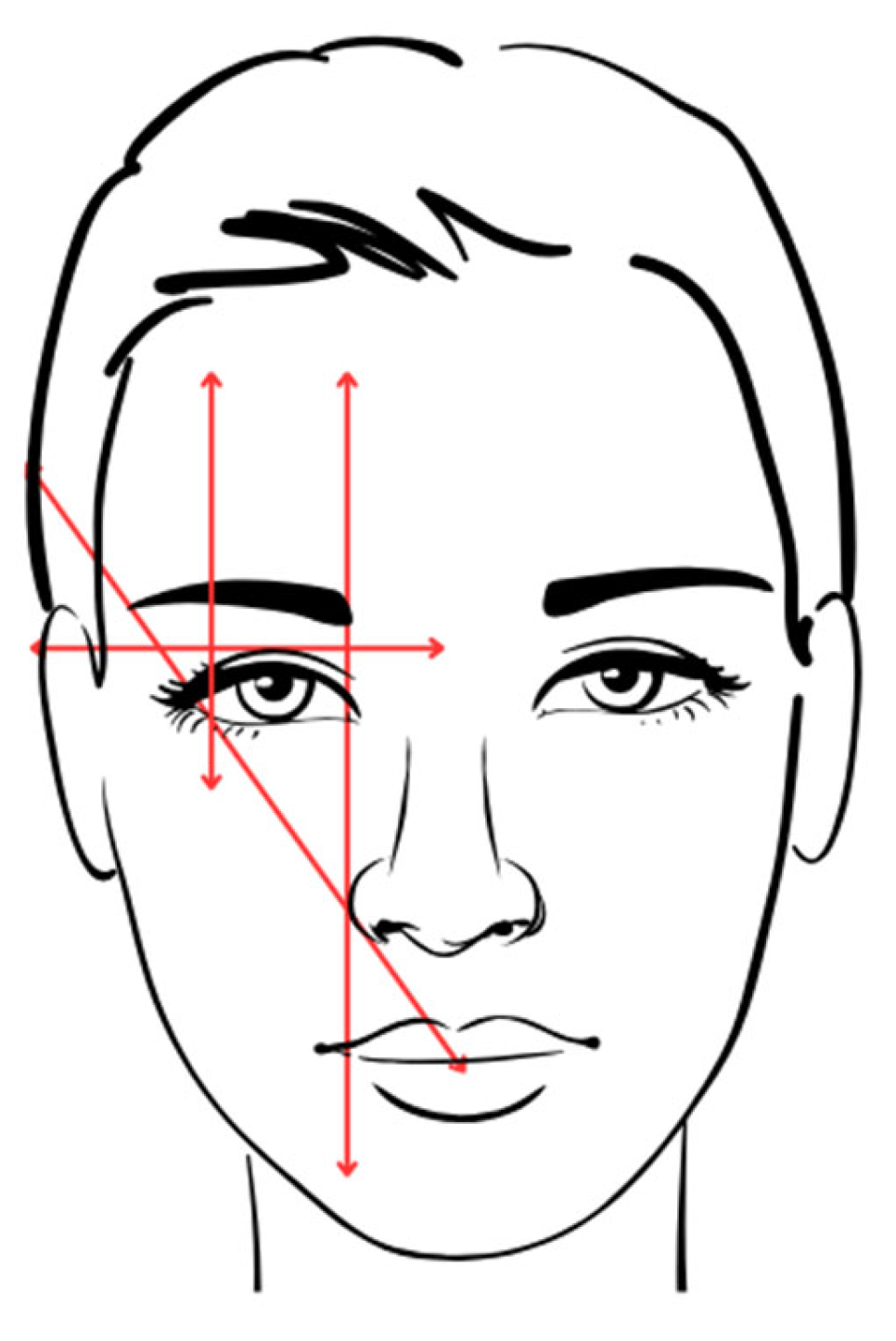

6.1. Frontal and Lateral View Analysis

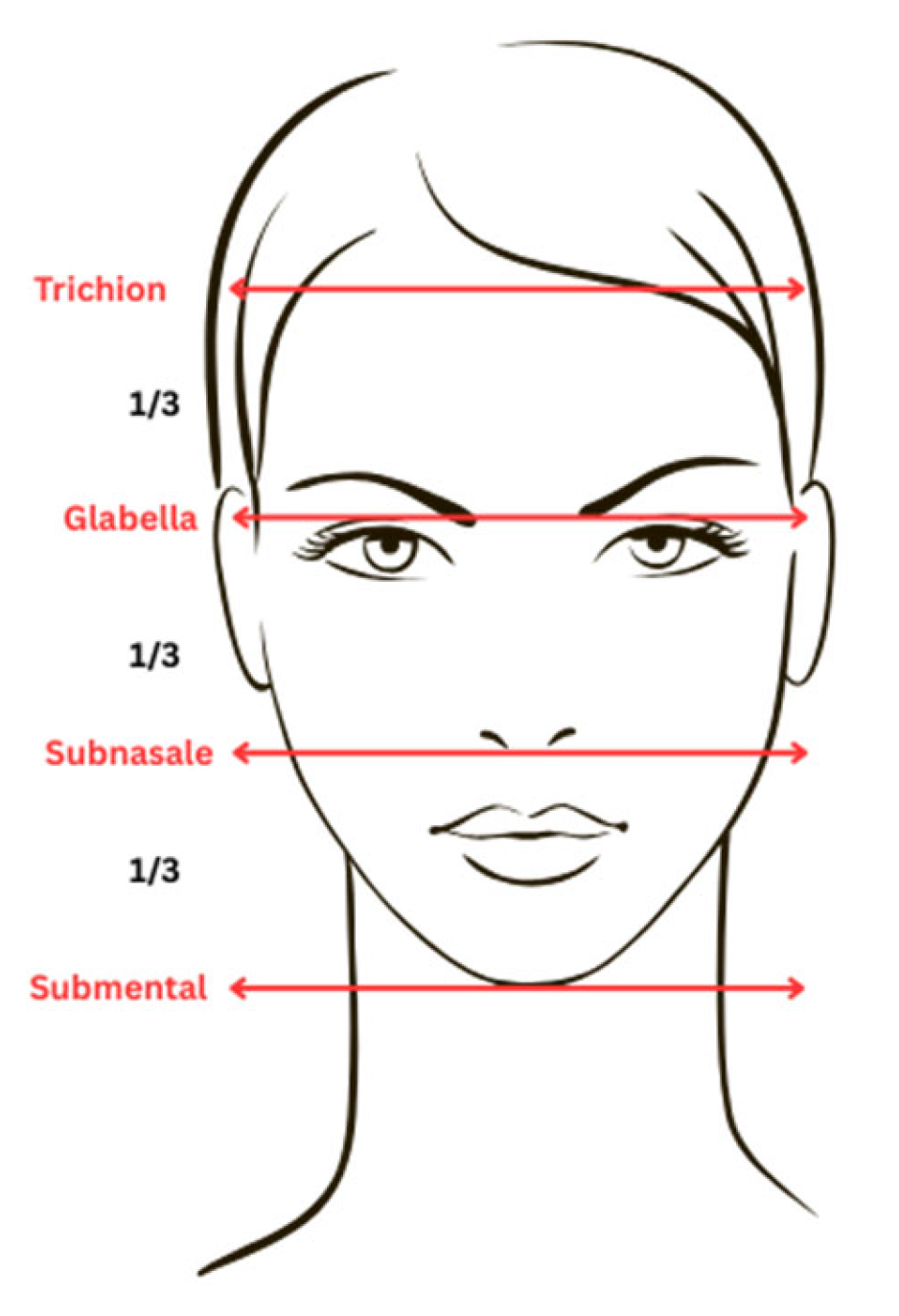

Facial analysis can be approached in several standardized ways to assess aesthetic harmony. In frontal view, overall symmetry is typically evaluated by drawing a vertical midline through the face and comparing right and left proportions. Vertical facial balance is often assessed by dividing the face into three approximate segments: the upper third extending from the hairline (trichion) to the glabella, the middle third from the glabella to the subnasale, and the lower third from the subnasale to the menton (

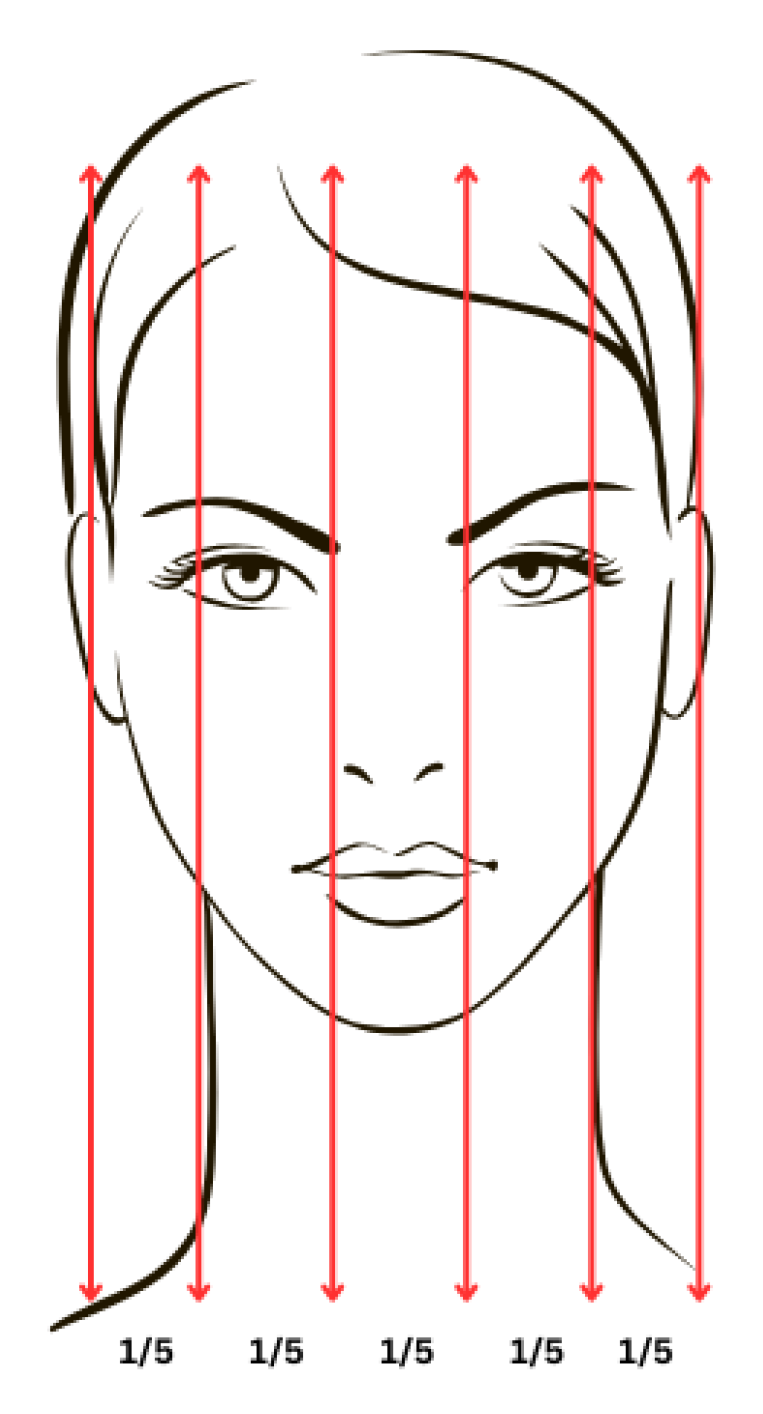

Figure 2). In individuals with a high or receding hairline, the superior limit of the upper third can instead be estimated at the highest point of frontalis contraction. Horizontal proportions can be evaluated by dividing the face into five roughly equal parts—one corresponding to the intercanthal width, two representing the width of each eye, and two extending laterally from the outer canthi to the helical rims (

Figure 3) [

32,

33].

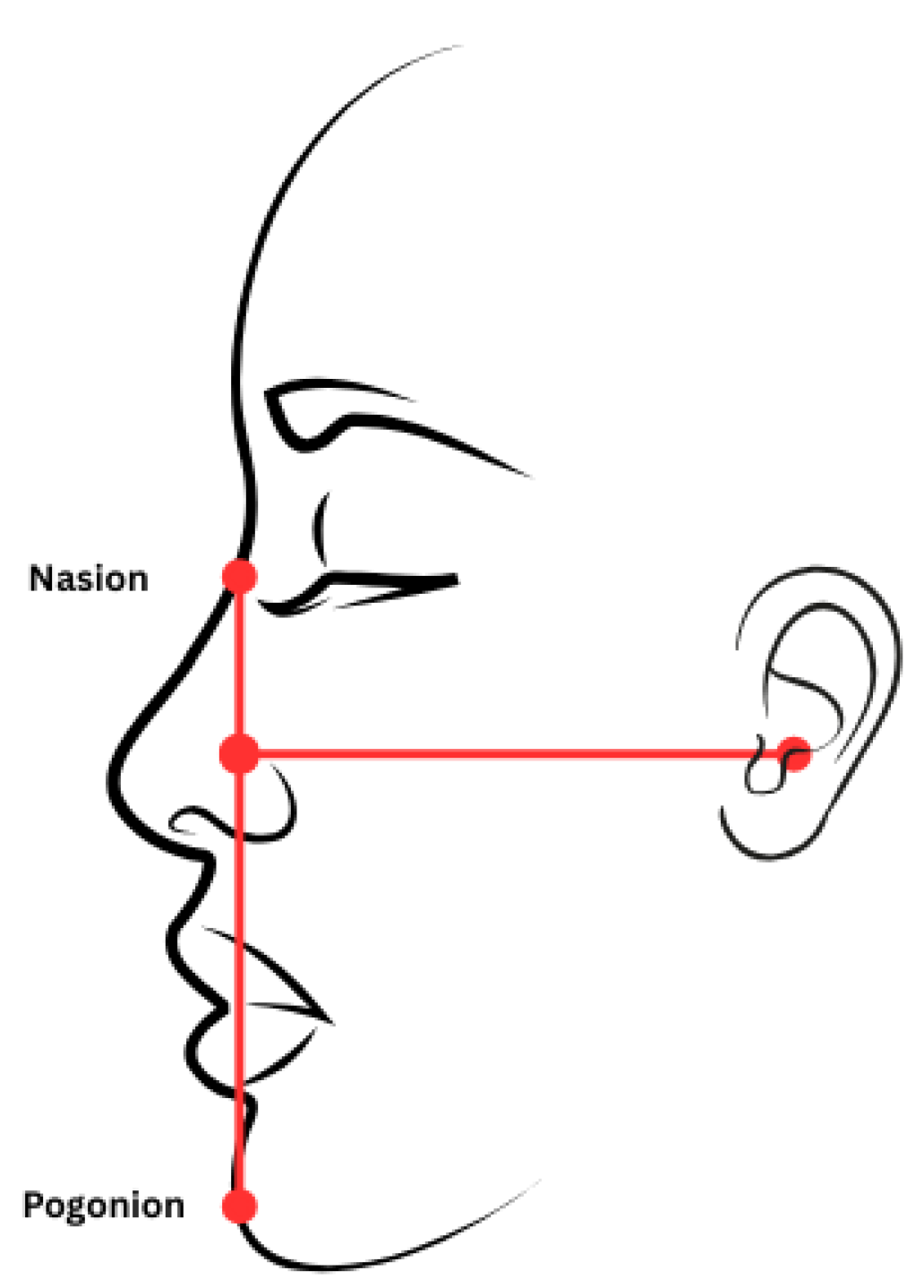

When assessing the facial profile (

Figure 4), vertical height and projection are the main parameters of interest. The Frankfort horizontal plane, which is drawn from the lowest point of the orbital rim to the tragion, serves as the reference baseline. For the midface, a line connecting the nasion and subnasale should ideally meet the Frankfort horizontal at roughly a right angle, which reflects a balanced anterior projection. In the lower third, a line from the subnasale to the pogonion (the point of greatest chin prominence) is evaluated in the same way; its relationship to the Frankfort plane helps identify chin retrusion or excessive projection. Together, these angular relationships create a standardized metric for ensuring harmony in lateral view [

32,

33].

6.2. Other Aesthetic Considerations

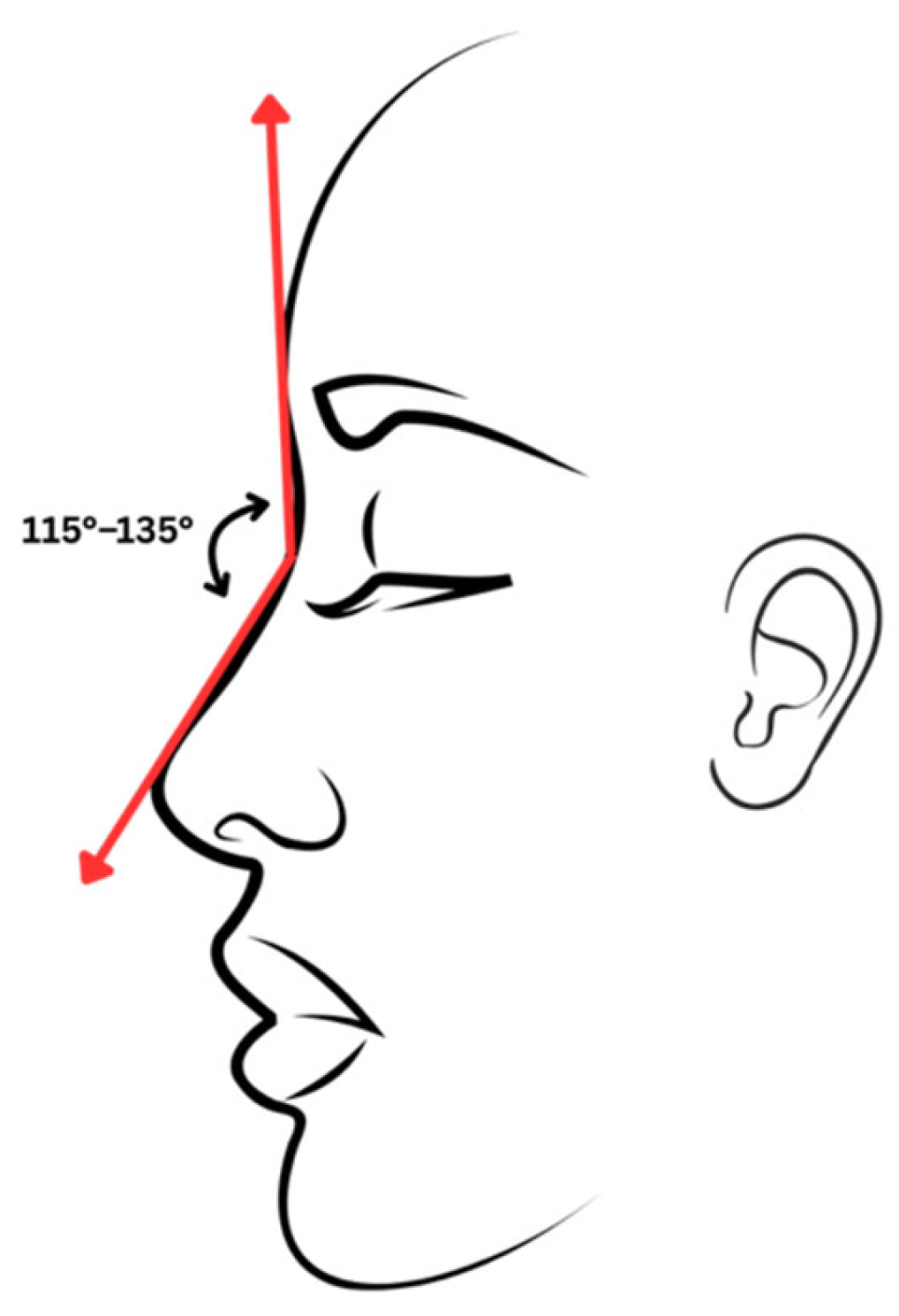

Foreheads are an aesthetic facial feature with a surprising level of variability. The forehead is typically convex on profile, with the most anterior point above the nasion at the level of the supraorbital ridge [

32,

34,

35]. Males tend to have a more prominent glabella and supraorbital rim compared to women due to differing frontal nasal sinus development [

32,

34]. In contrast, women tend to have a rounder, more convex contour. The nasofrontal angle, measured at the glabella, generally ranges from 115–135 degrees, which varies across gender, ethnicity, and age [

32,

34,

35] (

Figure 5).

The aesthetic brow for females begins medially above the medial canthus and alar base and ends laterally at an axis connecting the lateral canthus to the alar base. The peak of the brow lies 5–10 mm superior to the lid margin and above the lateral limbus. In contrast, the aesthetic male brow has no distinct peak but follows a gentle curve at the level of the supraorbital rim (

Figure 6) [

32,

34,

35].

It is critical to note that aesthetic ideals vary significantly across cultures, ethnicities, and historical contexts. Features regarded as attractive in one population may not hold the same value in another. Surgeons should therefore approach each patient with an individualized perspective, taking into account cultural background and personal preferences rather than adhering strictly to numerical ratios. This culturally informed approach broadens the understanding of beauty and challenges the idea of a singular, Western-defined aesthetic standard.

7. Evolution of Common Facial Cosmetic Procedures

7.1. Rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty, one of the oldest procedures in the field of plastic surgery, has evolved remarkably over time, encompassing approaches for both restoring functional deficits and for attaining modern aesthetic ideals. After Sushruta had laid the groundwork for rhinoplasties in ancient India with the forehead flap technique for reconstructive purposes [

36], the Italians of the 15th century played a key role in further refining the nasal reconstructive procedure by using skin grafts from the arm to augment nasal defects caused by scarring [

37]. And the German surgeon Karl von Graefe conceived the term “rhinoplasty” in his early 19th century text “

Rhinoplastik,” in which he described 3 unique rhinoplasty procedures: the forehead flap technique (Indian), the grafting method (Italian), and the modified free arm graft (German) [

11].

Advances continued into the 19th century, with Johann Dieffenbach introducing external incisions to correct nasal deformities in 1845 [

38]. John Orlando Roe was an American otolaryngologist whose endonasal rhinoplasty method was introduced in 1887, and Jacques Joseph’s external approach was debuted in 1898, both strategies highlighting the need for implementing structural corrections in addition to considering the psychological aspects of nasal procedures [

39]. By 1978, Sheen’s “Aesthetic Rhinoplasty” introduced a more balanced approach, combining reduction and grafting, contrasting with Joseph’s reduction-only approach [

40]. Modern advances made during both World Wars allowed for more detailed techniques in skin grafting and tissue manipulation, allowing for more precise procedures [

41]. Modern procedures including preservation rhinoplasty and the use of ultrasonic tools and non-surgical injectables have further transformed the field, offering sharp precision, shorter recovery times, and improved scar recovery.

Currently, rhinoplasty continues to be a highly customizable procedure that can not only drastically alter the patient’s physical appearance but also correct functional impairments to improve breathing and other pathologies. This makes rhinoplasty a powerful procedure for enhancing patient self-confidence and contributing to overall wellbeing. And the complex anatomy of the nose will ensure that needed surgical innovations will continue to arise into the future.

7.2. Blepharoplasty

The earliest descriptions of periocular surgery date back thousands of years. Ancient medical writings such as the

Ebers Papyrus (around 1550 BC) described techniques for treating eye conditions like ectropion and trichiasis [

42], while the

Edwin Smith Papyrus mentioned early suturing of the brow region [

43]. Even earlier references from Hammurabi’s Code suggest that procedures involving the lacrimal sac were performed as part of early ophthalmic care [

44]. Together, these texts show that surgery around the eyes was one of the first areas where medicine aimed to restore both function and appearance; principles that would eventually shape modern blepharoplasty.

The periocular region of the face plays an integral role in the human expression of emotions, mood, personality, and character, thus highlighting the ever-increasing prevalence and popularity of blepharoplasty (eyelid surgery) in modern-day cosmetic surgery. “Blepharon” means “eyelid”, and this term was originally coined by Karl Von Grafe in 1818 as he was the first to formally describe eyelid reconstruction [

45]. Before the 19th and 20th century advances, earlier approaches to blepharoplasty relied more upon aggressive tissue resection, often resulting in complications such as a hollowed eye appearance or an excessively shortened (“amputated”) eyelid. The French surgeon Suzanne Noel, in 1920, emphasized the importance of preoperative planning with photographs, further contributing to advancing safety standards for this delicate procedure [

46].

More recently, over the past 3 decades or so, the focus has shifted toward enhancing patient outcomes, improving patient comfort, and reducing associated complications. Whereas the foundational technique of blepharoplasty has remained consistent throughout history, the focus on enhanced patient safety and a greater emphasis on “fullness” of the eyelids with a concomitant reduction in “heaviness” has allowed for more conservative excision of eyelid structures and fat transfer when feasible.

7.3. Facelift

Historically, the facelift procedure first focused on a simple excision of skin, eventually shifting over time to isolated superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) manipulation [

47]. Over time, more modern approaches to performing facelifts have then shifted from SMAS manipulation to volume restoration [

48]. In 1901, Eugene von Holländer performed the first facelift, in which the elliptical skin surrounding the ear was removed. Prior to World War II, conservative surgical approaches were favoured due to limited infection control and pain management options. However, the widespread availability of antibiotics and anesthetics during and after the war enabled the adoption of more aggressive techniques. This period also marked a turning point in facial reconstructive surgery, as the specialty gained broader acceptance and became more mainstream, reducing the stigma previously associated with plastic surgery [

49,

50,

51].

Building on these early efforts, Erich Lexer introduced a more advanced facelift technique in 1916 that marked a shift in facial rejuvenation. His method involved lifting the facial skin from the underlying fat layer, repositioning it for a smoother contour, and trimming the excess [

52]. Lexer’s artistic background in sculpture influenced the precision of his approach, which became the dominant standard for the next several decades. Still, the results were often criticized for their overly tight appearance, described as the “wind tunnel” effect, due to the unnatural tension in the facial skin [

51,

52].

Later in 1968, Todd Skogg introduced a new approach to facelifting that involved manipulating deeper tissue layers, specifically through subfacial dissection, instead of depending solely on skin tension. By 1974, Skogg developed a technique that allowed dissection beneath the platysma muscle while preserving the overlying skin. In 1976, Mitz and Peyronie provided the first anatomical description of the SMAS facelift [

51,

53], although the term “SMAS” was coined later by French craniofacial and plastic surgeon Paul Tessier, who built on Skoog’s innovative work to refine facelift techniques. One of Tessier’s refinements developed around 1981 was the use of coronal incisions to adjust the eyebrow and soft tissues. And moving into the modern day, Sam Hamra developed a deep plane facelift technique using a plane of dissection below the SMAS and allowing for direct lysis of retaining ligaments and maximum mobilization of the superficial soft tissue [

51,

54]. Since then, modern facelift procedures have focused on reducing scarring and creating an effective result with minimal healing time. Also, “Mini facelifts” or “S-lifts” have been adopted as a less extensive version of the facelift.

7.4. Chemical Peeling Techniques

Facial resurfacing remains an important way to rejuvenate aging skin. For plastic surgeons, it is important to have a solid understanding of non-invasive facial rejuvenation techniques [

55]. The earliest forms of peeling date back to ancient Egypt, where women used sour milk containing lactic acid, an alpha-hydroxy acid, to smooth and refresh the skin [

56]. Later, dermatologists like Paul Gerson Unna and Ferdinand Hebra formalized the medical use of resorcinol, phenol, and salicylates for controlled peeling [

57].

Today, alpha hydroxy acids are used for superficial peels, trichloroacetic acid (20–35% TCA) for medium-depth peels, and phenol-based solutions for deep peels [

58]. The goal of chemical resurfacing is to stimulate collagen production and improve the appearance of acne scars, fine lines, photoaging, and hyperpigmentation [

59]. Peels are often used along with surgical procedures such as facelifts or laser treatments to enhance overall results. Although complications like redness, hyperpigmentation, and scarring can occur, recent advances in technique and formulation have made chemical peels a safe, effective, and affordable way to complement facial aesthetic surgery [

58,

59].

7.5. Otoplasty

The intricate anatomy of the ear provides an explanation for the challenges and ongoing refinement of otoplastic procedures, which have been refined over almost 200 years. The position of the auricle and its relation to the nasal region and brow are instrumental features to consider in the planning of the procedure [

60]. The aims of the otoplasty procedure are typically to address both functional and aesthetic issues of prominent ears. The first noted otoplasty technique took place in 1845, when Dieffenbach described the resection of retro auricular skin and concho-mastoid fixation to correct a post-traumatic auricular prominence [

61]. However, this technique had some limitations. Namely, the exclusive resection of postauricular skin only corrects the cephalo-auricular angle [

60] and does not address the cartilaginous forces involved in shaping the prominent ear, resulting in possible recurrence of the ear’s protrusion over time. But in 1881, Edward Talbot Ely (1850–1885), otherwise known as the “Father of Aesthetic Otoplasty” [

62] further refined the technique by including the excision of the conchal and triangular fossa cartilage [

63].

In 1910, Luckett addressed restoration of the anti-helical fold and widening of the concho-scaphal angle by adding a posterior excision of skin and cartilage, followed by closure with mattress sutures, which results in a sharp anti-helical border due to the full-thickness cartilage excision [

60,

64] Then, in 1963, the Mustarde technique was developed, which involved enhancing the antihelical fold with permanent concho-scaphal mattress sutures while avoiding cartilage excision [

65]. However, this technique only corrected the prominence of the upper third of the auricle, and further procedural refinements were needed for correcting the overdeveloped conchal bowl. Thus, in 1968, Furnas described a concho-mastoid fixation suture technique for reducing the helix-mastoid distance. In this technique, retro auricular soft tissues, including posterior auricular muscle and ligament, are resected and attached by 3 to 4 nonabsorbable mattress sutures to set the conchal bowl as far back as the mastoid [

66], and the procedure is typically performed alongside anti-helical fold reconstruction.

In more recent times, less invasive techniques for otoplasty have been developed with the hopes of reducing postoperative complications, for example, hematomas, asymmetry, and scarring, among others. This can be seen in Fritsch’s “suture-only” technique, or Peled’s “incisionless otoplasty”, and finally Graham and Gault’s retro-auricular approach utilizing an endoscope advanced along a small incision in the hairline [

67].

The development of otoplasty marked a shift from purely reconstructive goals to a focus on aesthetics. Dieffenbach set the foundation for aesthetic ear surgery by using carefully planned incisions to correct auricular deformities [

61]. Ely, Luckett, and later Mustardé advanced these ideas with suture-based contouring techniques, paving the way for more refined and minimally invasive approaches. Together, these milestones illustrate how the study of auricular anatomy contributed to a broader principle in aesthetic surgery: understanding the natural proportions and operating with precision while minimizing the intervention. The evolution of key facial aesthetic procedures demonstrates how early reconstructive principles have been refined into more modern and patient-centered techniques.

8. Current Trends in Aesthetic Surgery

According to the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (AAFPRS), in 2023, facelifts were the most highly requested cosmetic procedure, followed by rhinoplasties and blepharoplasties [

68]. In fact, the number of facelifts performed has been increasing annually, with a 60% increase in 2017 alone [

68]. This same survey reported younger patients are now opting for facelifts, with patient ages ranging from 35 to 55 years. Interestingly, the rising rate of facelift procedures in a younger population may in part be due to the growing use GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as Ozempic, for weight-loss. Semaglutides can lead to significant weight loss in a short period, which may result in skin laxity that many individuals seek to address cosmetically.

Men are also increasingly becoming involved in the culture of plastic surgery. While aesthetic procedures have been traditionally sought mainly by women, the development of minimally invasive techniques is reducing the gender divide [

68]. Overall, patients are now more focused on surgical procedures that enhance their individuality, rather than on results that make it obvious surgery had been performed. In fact, 24% of the AAFPRS survey respondents reported that the patient’s biggest fear revolved around looking unnatural after a facial procedure [

68].

Plastic surgery as a form of preventive medicine at a younger age has been rising in line with the unique values of Generation Z. And with the increasing use of social media, younger populations have more exposure to the many possibilities of aesthetic treatments. The AAFPRS reported that a whopping 75% of facial plastic surgeons have seen sharp rises in demand from patients under the age of 30, particularly for minimally invasive procedures, such as lip filling and blepharoplasty, that require minimal downtime [

69].

Additionally, the rise of social media filters has allowed people to visualize altered versions of their appearance, such as enhanced skin smoothness or alteration of facial structure, prompting a growing number to pursue cosmetic procedures that replicate their “filtered” selves. However, a phenomenon known as “Snapchat Dysmorphia” describes an obsessive and unhealthy desire to look like an edited version of oneself, which poses a unique ethical challenge for aesthetic surgeons [

69].

The rising popularity of social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube has brought widespread attention to cosmetic procedures, making aesthetic medicine more mainstream and accessible. However, this increased exposure raises concerns about long-term implications. The normalization of aesthetic procedures, particularly among younger patients, may influence how future generations perceive aging, self-image, and the need for cosmetic intervention. Studies have shown links between social media use and unrealistic body image expectations, sometimes leading to conditions such as body dysmorphia [

70].

The use of GLP-1 agonists, such as Ozempic, for cosmetic weight loss has introduced new considerations within plastic surgery. However, there is still limited data on how these medications may affect long-term surgical planning, tissue healing, or patient satisfaction [

71]. As social media continues to amplify public interest in GLP-1 use, it is essential for surgeons to stay informed about these trends and their social influence. Surgeons should counsel patients thoughtfully, emphasizing safety, realistic expectations, and overall well-being.

9. Technological Advancements

Numerous recent advances in technology are being taken advantage of within the context of cosmetic surgery. Facial plastic surgeons must have a deep understanding of anatomic relationships when performing aesthetic procedures, and three-dimensional (3D) printing is a recent technical advance that can be used by surgeons for preoperative visualization and planning, as well as for implant fabrication. For fat grafting procedures, precise presurgical planning to determine the exact location for the fat injection and the amount of fat needed can greatly affect patient outcomes [

72]. These preoperative planning steps have traditionally relied on surgeon experience. However, 3D printed masks can provide a surgical guide to improve the accuracy of volume enhancement, which is particularly important for patients with complex facial anatomy [

72].

Virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) are other technical advances that have been used to guide surgeons during various cosmetic procedures, including dermal filler planning, rhinoplasty, and facial artery mapping; similar technologies are also being adapted for complex reconstructive cases [

73]. VR and AR can also strengthen surgeons’ understanding of patient-specific anatomical relationships, providing more nuanced information for preoperative planning [

73]. These tools are also helpful for patients, allowing them to “try on” different procedures before committing to surgery and helping them better understand the limitations and possibilities of procedural outcomes. Thus, the use of AR and VR by both patients and surgeons can help minimize miscommunication, ultimately enhancing postoperative satisfaction.

And lastly, artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools such as “chatbots” and specialized medical devices allow for the analysis of large volumes of data to make predictions via pattern recognition [

74]. Facial plastic surgery relies on clinical expertise and artistic vision to restore form and function to the face. AI-based tools can provide advanced analytics for aesthetic planning through predictive modelling, positioning it as a transformative tool for complex surgical decision-making. Some surgical devices developed by companies such as Proximie have AI-based analytics for postoperative analysis of procedures recorded with their “smart glasses,” which surgeons wear to record procedures in real time. These AI-analytics also allow for large pools of surgical videos to be aggregated and assessed, providing insights into workflow inefficiency, safety concerns and areas for improvement [

75]. Future AI-based device integrations may eventually guide instrument use during surgery, predict possible complications, and even recommend procedural steps.

While technological advancements are an exciting and promising avenue, integrating them into everyday surgical practice remains challenging due to high costs, concerns about patient privacy, and limited accessibility [

76]. There are also ethical concerns surrounding the use of AI tools, including the potential for misinformation, data privacy issues, and racial bias [

77]. The widespread use of social media filters and the constant exposure to altered facial images add another layer of complexity, making it more difficult to manage patient expectations while maintaining professional integrity [

78]. Increased training, standardized oversight, and thoughtful regulation are essential to ensure these technologies are implemented safely and help close gaps in care rather than widen them. Overall, AI represents the latest leap in medical advances, and the immense possibilities are only now beginning to emerge.

10. Conclusions

Aesthetic surgery has undergone profound changes over the course of history. Understanding the histories of reconstructive and aesthetic surgery can inform surgeons of how principles developed for functional restoration have grown into tools for elective cosmetic refinement. The conflict between attaining both practical and cosmetic goals will continue to drive the field of plastic surgery, as changes in cultural values and advances in technology, including 3-D printing and AI, play a greater role in surgical decision-making. As the field of aesthetic surgery continues to evolve, professionals must maintain vigilant awareness regarding the benefits and risks of new technologies, while prioritizing patient safety and satisfaction.

Understanding the history of aesthetic surgery helps surgeons balance artistry with ethical principles and remember that patient safety should always come first, especially in times of rapid innovation. This perspective encourages honest conversations with patients, realistic expectations, and a focus on individualized care. A deeper understanding of the field’s historical roots can also help trainees recognize how beauty ideals have evolved over time and why diversity in aesthetic standards should be considered when managing patients.

In addition, new technologies in plastic surgery should be developed and implemented with rigorous safety standards that prioritize both patient well-being and privacy. With the growing influence of AI tools and social media, practitioners must stay aware of how public awareness and perception of aesthetic procedures are changing and help guide patients toward informed, thoughtful decision-making.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception, drafting, and revision of this manuscript and approved the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. All materials used are publicly accessible through previously published sources as referenced in the manuscript, consistent with MDPI Research Data Policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Summer Yono and Karla Passalacqua for their support and guidance during the preparation of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whitaker, I.S.; Karoo, R.O.; Spyrou, G.; Fenton, O.M. The Birth of Plastic Surgery: The Story of Nasal Reconstruction from the Edwin Smith Papyrus to the Twenty-First Century. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroline, M.W.; Sahar, N.S.; Ching, Y.J.L.; Mark, R. Revealing the face of Ramesses II through computed tomography, digital 3D facial reconstruction and computer-generated Imagery. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2023, 160, 105884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, M.C.; Buvariya, S.; Krishna, A.G.; Singh, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Tiwari, R. The father of oral and maxillofacial surgery, “Sushruta the legend”: An overview. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2024, 12, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bhishagratna, K.K. The Sushruta Samhita: An English Translation Based on Original Sanskrit Text; Bose Brothers: Calcutta, India, 1907; Available online: https://archive.org/details/englishtranslati01susruoft (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Dave, T.; Habte, A.; Vora, V.; Sheikh, M.Q.; Sanker, V.; Gopal, S.V. Sushruta: The Father of Indian Surgical History. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, e5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatchford, J.W., III. The Surgery of Celsus’ De Medicina. Ann. Surg. Open 2024, 5, e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsus, A. De Medicina. Translated by W.G. Spencer; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1935; Available online: https://archive.org/details/demedicina02celsuoft (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ménard, S. An Unknown Renaissance Portrait of Tagliacozzi (1545–1599), the Founder of Plastic Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.A. The Tagliacozzi Flap as a Method of Nasal and Palatal Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1985, 76, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliacozzi, G. De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem; Gaspare Bindoni: Venice, Italy, 1597; Available online: https://collections.library.utoronto.ca/view/anatomia%3ARBAI096 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- von Graefe, K. Rhinoplastik; Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1818; Available online: https://archive.org/details/rhinoplastikoder00grae/page/n3/mode/2up?ref=ol (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Macionis, V. History of plastic surgery: Art, philosophy, and rhinoplasty. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 71, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoutzanis, C.; Winocour, J.; Unger, J.; Gabriel, A.; Maxwell, G.P. The Evolution of Breast Implants. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2019, 33, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uroskie, T.W.; Colen, L.B. History of Breast Reconstruction. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2004, 18, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Goel, A. From Quackery to Super-Specialization: A Brief History of Aesthetic Surgery. Indian J. Plast. Surg. 2024, 57, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.C. Cosmetic Surgery: The Correction of Featural Imperfections; Oak Printing Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1907; Available online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011681882 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Mazzola, R.F. Commentary on: The 19th Century Origins of Facial Cosmetic Surgery and John H. Woodbury. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2015, 35, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkler, K.A.; Hudson, R.F. The 19th Century Origins of Facial Cosmetic Surgery and John H. Woodbury. Aesthetic Surg. J. 2015, 35, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mironica, A.; Popescu, C.A.; George, D.; Tegzeșiu, A.M.; Gherman, C.D. Social media influence on body image and cosmetic surgery considerations: A systematic review. Cureus 2024, 16, e65626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge University. Beauty. Cambridge English Dictionary [Internet]. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/beauty (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Sisti, A.; Aryan, N.; Sadeghi, P. What is Beauty? Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2021, 45, 2163–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselinoff, C. Apophatic Beauty in the Hippias Major and the Symposium. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2024, 82, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashi, N.A. (Ed.) Beauty and Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Clinician’s Guide; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, J.H.; Roggman, L.A.; Musselman, L. What Is Average and What Is Not Average About Attractive Faces? Psychol. Sci. 1994, 5, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, J.H.; Roggman, L.A. Attractive Faces Are Only Average. Psychol. Sci. 1990, 1, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Adaptive significance of female physical attractiveness: Role of waist-to-hip ratio. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, B.; Grammer, K.; Thornhill, R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness in relation to skin texture and color. J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamargo, R.J.; Pindrik, J.A. Mammalian Skull Dimensions and the Golden Ratio (Φ). J. Craniofacial Surg. 2019, 30, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milutinovic, J.; Zelic, K.; Nedeljkovic, N. Evaluation of Facial Beauty Using Anthropometric Proportions. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 428250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oranges, C.M.; Largo, R.D.; Schaefer, D.J. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man: The Ideal Human Proportions and Man as a Measure of All Things. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 137, 764e–765e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galantucci, L.M.; Percoco, G.; Lavecchia, F.; Di Gioia, E. Noninvasive Computerized Scanning Method for the Correlation Between the Facial Soft and Hard Tissues for an Integrated Three-Dimensional Anthropometry and Cephalometry. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2013, 24, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, K.S.; Vasconez, H.C. 6 Principles of Facial Aesthetics. Plastic Surgery Key [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://plasticsurgerykey.com/6-principles-of-facial-aesthetics/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Naini, F.B. Facial Aesthetics: Concepts & Clinical Diagnosis; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781118786567.fmatter (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Toledo Avelar, L.E.; Cardoso, M.A.; Santos Bordoni, L.; de Miranda Avelar, L.; de Miranda Avelar, J.V. Aging and Sexual Differences of the Human Skull. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2017, 5, e1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgh, J. The Aesthetics of the Upper Face and Brow: Male and Female Differences. Facial Plast. Surg. 2018, 34, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaye, D.A. The history of nasal reconstruction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 29, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, I.C.; Mazzola, R.F. History of Reconstructive Rhinoplasty. Facial Plast. Surg. 2014, 30, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, R.F.; Marcus, S. History of Total Nasal Reconstruction with Particular Emphasis on the Folded Forehead Flap Technique. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1983, 72, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.M. John Orlando Roe: Father of Aesthetic Rhinoplasty. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2002, 4, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J.H. Rhinoplasty: Personal Evolution and Milestones. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2000, 105, 1820–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treger, D.; Taylor, R.; Prasad, S.; Thaller, S.R. Plastic Surgery Contributions to the World Wars: Historical Foundations for Modern Craniofacial Techniques. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2025, 36, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, D.M.; Diane, D.E. The History of Ophthalmology; Blackwell Science: Cambridge, UK, 1996. Available online: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma998127083406676&context=L&vid=01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST&lang=en&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=LibraryCatalog&query=lds56,contains,Ophthalmology,AND&mode=advanced&offset=250 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Aston, S.J. (Ed.) Third International Symposium of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Eye and Adnexa; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1982. Available online: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma995401283406676&context=L&vid=01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST&lang=en&search_scope=MyInstitution&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=LibraryCatalog&query=lds56,contains,Ophthalmologic%20Surgical%20Procedures,AND&mode=advanced&offset=340 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Hirschberg, J. The History of Ophthalmology; Wayenborgh: Bonn, Germany, 1982. Available online: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma995950933406676&context=L&vid=01NLM_INST:01NLM_INST&lang=en&search_scope=MyInstitution&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&isFrbr=true&tab=LibraryCatalog&query=lds56,contains,Ophthalmology,AND&mode=advanced&offset=230 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Bhattacharjee, K.; Misra, D.K.; Deori, N. Updates on upper eyelid blepharoplasty. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastic Surgery Key. History of Techniques: Early Blepharoplasty Involved Aggressive Resection Often Resulting in Hollowed Eyes or “Amputated” Eyelids; Suzanne Noël in 1920 Emphasized Preoperative Photography Planning. Plastic Surgery Key [Internet]. 2017. Available online: https://plasticsurgerykey.com/history-of-techniques/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Charafeddine, A.H.; Drake, R.; McBride, J.; Zins, J.E. Facelift: History and anatomy. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2019, 46, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrich, R.J.; Durand, P.D.; Dayan, E. The Lift-and-Fill Facelift: Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System Manipulation with Fat Compartment Augmentation. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2019, 46, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangat, D.; Frankel, J. The History of Rhytidectomy. Facial Plast. Surg. 2017, 33, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.J.; Hohman, M.H. Rhytidectomy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564338/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Ashary, I.A. Mesh Induced Permanent Surgical Facelift-Modification of Surgical Face-Lifting. MAR Case Rep. 2023, 6, 1–7. Available online: https://www.medicalandresearch.com/assets/articles/documents/DOCUMENT_1749919320684da65888c3cMARDS_346.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Locher, W.G.; Feinendegen, D.L. Aus der Frühzeit der Ästhetischen Chirurgie: Eugen Holländer (1867–1932) und Erich Lexer (1867–1937) als Face-Lift-Pioniere. Handchir. Mikrochir. Plast. Chir. 2020, 52, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitz, V.; Peyronie, M. The superficial musculo-aponeurotic system (SMAS) in the parotid and cheek area. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1976, 58, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamra, S.T. The deep-plane rhytidectomy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1990, 86, 53–61. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2359803/ (accessed on 31 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meaike, J.D.; Agrawal, N.; Chang, D.; Lee, E.I.; Nigro, M.G. Noninvasive Facial Rejuvenation. Part 3: Physician-Directed—Lasers, Chemical Peels, and Other Noninvasive Modalities. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2016, 30, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Shang, J.; Gu, Z.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Lactic Acid Chemical Peeling in Skin Disorders. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, C.; Ursin, F.; Steger, F. The rise of Chemical Peeling in 19th-century European Dermatology: Emergence of agents, formulations and treatments. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C.; Wambier, C.G.; Soon, S.L.; Sterling, J.B.; Landau, M.; Rullan, P.; Brody, H.J. Basic chemical peeling: Superficial and medium-depth peels. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 81, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, T.; Lanoue, J.; Rahman, Z. A Practical Approach to Chemical Peels: A Review of Fundamentals and Step-by-step Algorithmic Protocol for Treatment. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nazarian, R.; Eshraghi, A.A. Otoplasty for the Protruded Ear. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2011, 25, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieffenbach, J.F. Die Operative Chirurgie; F. A. Brockhaus: Leipzig, Germany, 1845; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Die_operative_Chirurgie.html?id=72WVzwEACAAJ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Lam, S.M. Edward Talbot Ely: Father of aesthetic otoplasty. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2004, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenda, E.; Marques, A.; Pereira, M.D.; Zantut, P.E. Otoplasty and its origins for the correction of prominent ears. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 1995, 23, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.O. The classic reprint. A New Operation for Prominent Ears Based on the Anatomy of the Deformity by William H. Luckett, M.D. (reprinted from Surg. Gynec. & Obst., 10: 635-7, 1910). Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1969, 43, 83–86. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4885279/ (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Mustardé, J.C. The correction of prominent ears using simple mattress sutures. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1963, 16, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnas, D.W. Correction of prominent ears by conchamastoid sutures. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1968, 42, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumann, A. Otoplasty–techniques, characteristics and risks. GMS Curr. Top. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007, 6, doc04. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3199845/ (accessed on 31 July 2025). [PubMed]

- American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. AAFPRS Unveils Aesthetic Statistics from Annual Facial Plastic Surgery Survey; AAFPRS: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.aafprs.org/Media/Press_Releases/2024_02_01_PressRelease.aspx (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New Trends in Facial Plastic Surgery: Minimally Invasive ‘Tweakments’ Now Comprise 82% of Procedures; Facelift and Rhinoplasty Surging in Demand; AAFPRS: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.aafprs.org/Media/Press_Releases/New-Trends-in-Facial-Plastic-Surgery.aspx (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Laughter, M.R.; Anderson, J.B.; Maymone, M.B.C.; Kroumpouzos, G. Psychology of aesthetics: Beauty, social media, and body dysmorphic disorder. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 41, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.H.; Ockerman, K.; Furnas, H.; Mars, P.; Klenke, A.; Ching, J.; Momeni, A.; Sorice-Virk, S. Practice Patterns and Perspectives of the Off-Label Use of GLP-1 Agonists for Cosmetic Weight Loss. Aesthetic. Surg. J. 2024, 44, NP279–NP306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E.; Huang, Y.-H.; Zhao, L.; Seelaus, R.; Patel, P.; Cohen, M. Virtual Surgical Planning and Three-Dimensional Printed Guide for Soft Tissue Correction in Facial Asymmetry. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, N.; Marques, M.; Scharf, I.; Yang, K.; Alkureishi, L.; Purnell, C.; Patel, P.; Zhao, L. Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality in Plastic and Craniomaxillofacial Surgery: A Scoping Review. Bioengineering 2023, 17, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune-Ely, M.; Achanta, M.; Song, M.S.H. The future of artificial intelligence in facial plastic surgery. JPRAS Open 2023, 39, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proximie. Proximie launches PxLens smart glasses with 4K camera to digitize operating and diagnostic rooms. Tech Funding News, 3 April 2023. Available online: https://www.techfundingnews.com/proximie-launches-pxlens-smart-glasses-with-4k-camera-to-digitise-operating-and-diagnostic-rooms/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Duong, T.V.; Vy, V.P.T.; Hung, T.N.K. Artificial Intelligence in Plastic Surgery: Advancements, Applications, and Future. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffourc, M.; Gerke, S. Generative AI in Health Care and Liability Risks for Physicians and Safety Concerns for Patients. JAMA 2023, 330, 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, E.M.; Román Ledesma, S.; Acosta Matos, J.A.; Castillo Cortorreal, M.E.; Goncharova, I.; Rivera Bonilla, R.B.; Rosario, R.A.; Encarnación Ramirez, M.J. Influence of Social Media Filters on Plastic Surgery: A Surgeon’s Perspective on Evolving Patient Demands. Cureus 2025, 17, e80483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).