Development of a Screening Measure to Identify Breast Appearance Dissatisfaction in Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Measures and Their Limitations

1.2. The Current Study

1.3. The Breast Appearance Concerns Scale (BACS)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Analysis Overview

2.2.2. Statistical Methods

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.3.2. Body Image-Related Measures

2.3.3. Mood-Related Measures

2.3.4. New Measure

3. Results

3.1. EFA Results

3.2. CFA Results

3.3. Internal Consistency

3.4. Test–Retest Reliability

3.5. Construct Validity

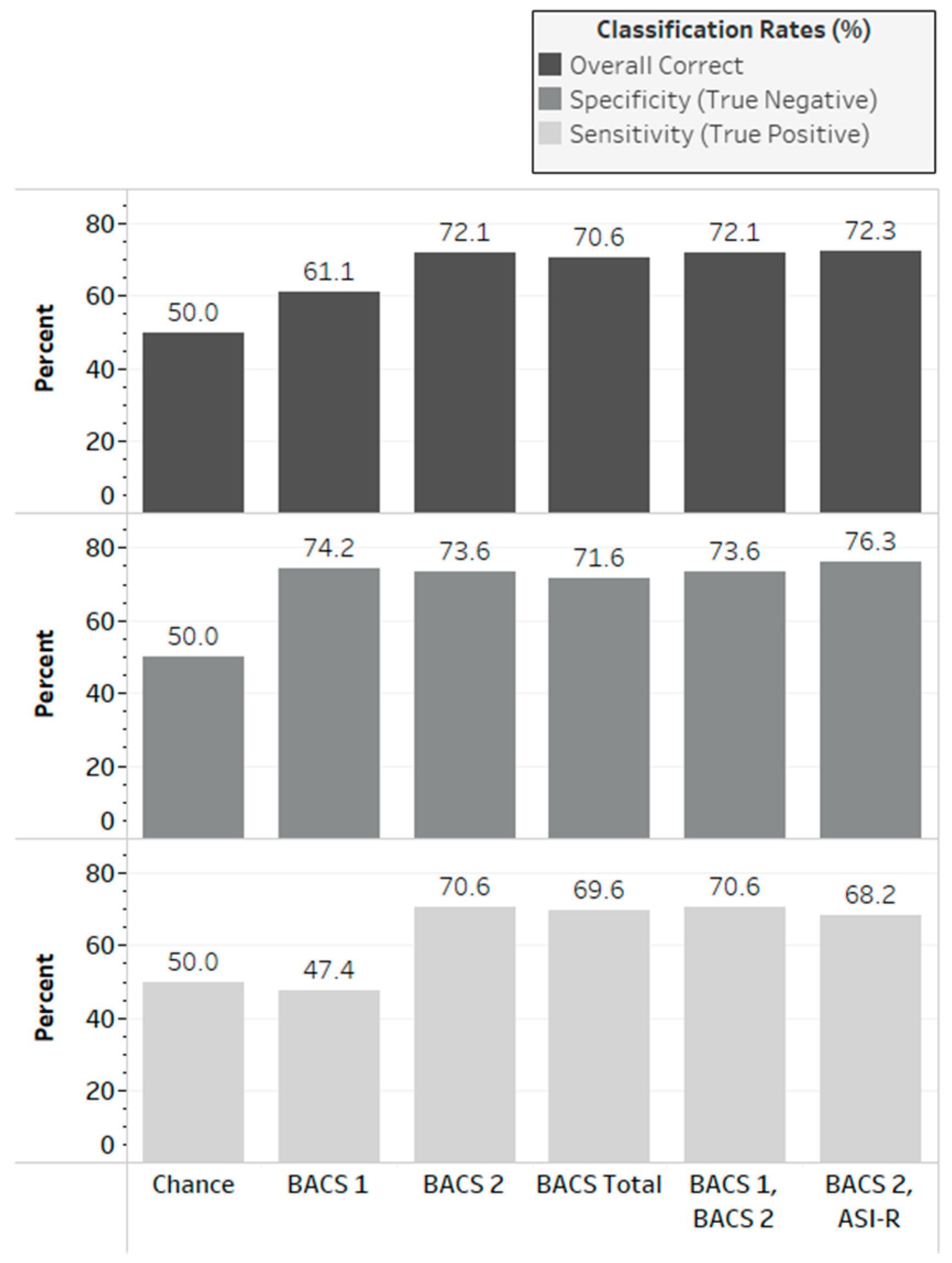

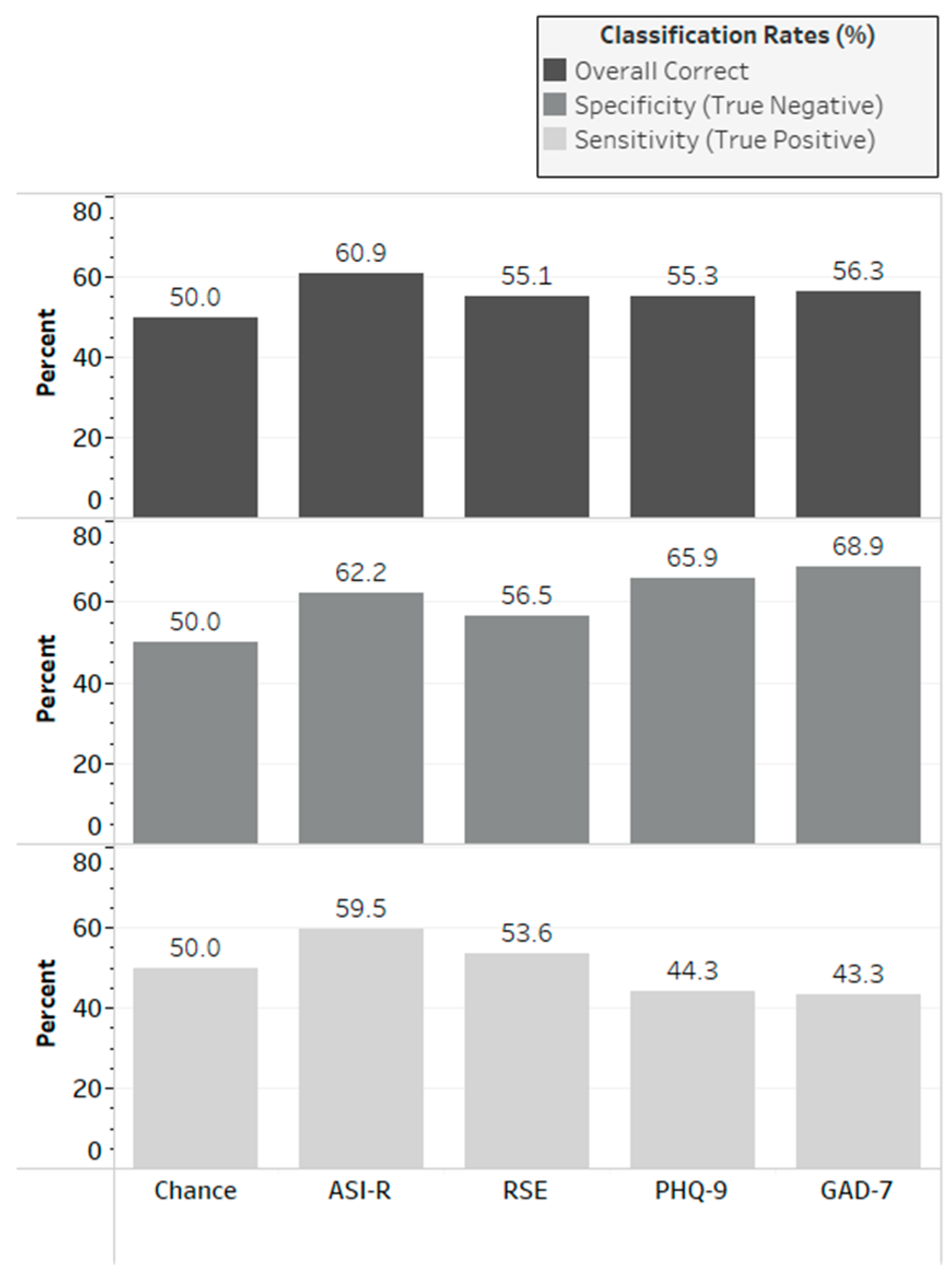

3.6. Predictive Validity

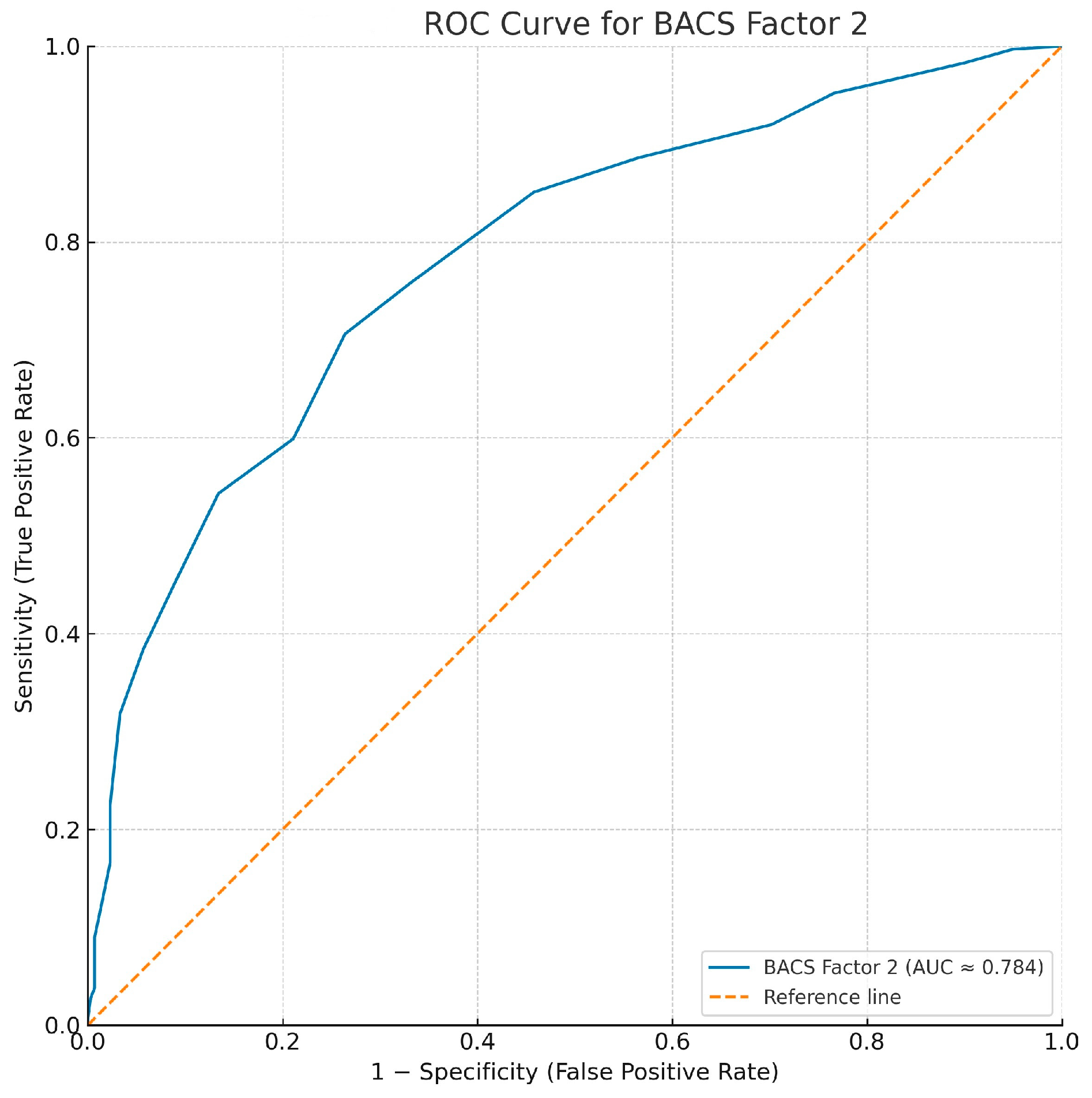

3.7. Clinical Cutoff Determination

3.8. Exploratory Analysis by Racial/Ethnic Group

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Clinical Utility and Theoretical Implications

4.2. Ethical & Diversity Considerations

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBS | Cosmetic breast surgery |

| NAC | Nipple–areola complex |

| BACS | Breast Appearance Concerns Scale |

| ASI–R | Appearance Schemas Inventory–Revised |

| BIBCQ | Body Image after Breast Cancer Questionnaire |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| RSE | Rosenberg Self-Esteem |

| PHQ–9 | Patient Health Questionnaire–9 |

| GAD–7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 |

| MBSRQ | Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire |

| BESAA | Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults |

References

- Cash, T.F.; Smolak, L. Understanding Body Images: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. In Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-1-60918-182-6. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-Discrepancy: A Theory Relating Self and Affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.D.; Perri, M.G.; Riley, J.R. Discrepancy between Actual and Ideal Body Images: Impact on Eating and Exercise Behaviors. Eat. Behav. 2000, 1, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mond, J.; Mitchison, D.; Latner, J.; Hay, P.; Owen, C.; Rodgers, B. Quality of Life Impairment Associated with Body Dissatisfaction in a General Population Sample of Women. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solvi, A.S.; Foss, K.; von Soest, T.; Roald, H.E.; Skolleborg, K.C.; Holte, A. Motivational Factors and Psychological Processes in Cosmetic Breast Augmentation Surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2010, 63, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Soest, T.; Torgersen, L.; Kvalem, I.L. Mental Health and Psychosocial Characteristics of Breast Augmentation Patients. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Melnyk, S.E.; Hrabosky, J.I. The Assessment of Body Image Investment: An Extensive Revision of the Appearance Schemas Inventory. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, R.; Robertson, N. Psychological Adjustment to Lower Limb Amputation amongst Prosthesis Users. Disabil. Rehabil. 2006, 28, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarry, J.L.; Dignard, N.A.L.; O’Driscoll, L.M. Appearance Investment: The Construct That Changed the Field of Body Image. Body Image 2019, 31, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, H.; Canavarro, M.C. A Longitudinal Study about the Body Image and Psychosocial Adjustment of Breast Cancer Patients during the Course of the Disease. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 14, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Grift, T.C.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Elfering, L.; Özer, M.; Bouman, M.-B.; Buncamper, M.E.; Smit, J.M.; Mullender, M.G. Body Image in Transmen: Multidimensional Measurement and the Effects of Mastectomy. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1778–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, S.J.; Gullyas, C.; Hogg, F.J.; Power, K.G. Psychosocial Predictors of Body Image Dissatisfaction in Patients Referred for NHS Aesthetic Surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2018, 71, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Soest, T.; Kvalem, I.L.; Roald, H.E.; Skolleborg, K.C. The Effects of Cosmetic Surgery on Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Psychological Problems. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 62, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowska, A.; Zaborski, D.; Modrzejewski, A.; Pastucha, M. The Effect of Cosmetic Surgery on Mental Self-Image and Life Satisfaction in Women Undergoing Breast Augmentation: An Intermediate Role of Evaluating the Surgery as One of the Most Important Life Events. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2022, 75, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, N. The Body Image After Breast Cancer Questionnaire, the Design and Testing of a Disease-Specific Measure. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canda, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, N.N.; Goodwin, P.J.; Mcleod, R.S.; Dion, R.; Devins, G.; Bombardier, C. Reliability and Validity of the Body Image after Breast Cancer Questionnaire. Breast J. 2006, 12, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, S.J.; Klassen, A.F.; Scott, A.M.; Pusic, A.L. A Closer Look at the BREAST-Q. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2013, 40, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pusic, A.L.; Klassen, A.F.; Scott, A.M.; Klok, J.A.; Cordeiro, P.G.; Cano, S.J. Development of a New Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Breast Surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009, 124, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.F.; Dominici, L.; Fuzesi, S.; Cano, S.J.; Atisha, D.; Locklear, T.; Gregorowitsch, M.L.; Tsangaris, E.; Morrow, M.; King, T.; et al. Development and Validation of the BREAST-Q Breast-Conserving Therapy Module. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 2238–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif Nia, H.; Firouzbakht, M.; Rekabpour, S.-J.; Nabavian, M.; Nikpour, M. The Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Body Image after Breast Cancer Questionnaire: A Second- Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 3924–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.; Proctor, M.; Cassisi, J.E. The Application of Medical Tattooing in Cosmetic Breast Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10, e4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.J.; Cassisi, J.E. Applications of Medical Tattooing: A Systematic Review of Patient Satisfaction Outcomes and Emerging Trends. Aesthetic Surg. J. Open Forum 2021, 3, ojab015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, R.; Amoroso, M.; Plate, N.; Trogen, C.; Selvaggi, G. The Aesthetically Ideal Position of the Nipple-Areola Complex on the Breast. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.-W.; Park, S.O.; Jin, U.S. A Nipple-Areolar Complex Reconstruction in Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Using a Local Flap and Full-Thickness Skin Graft. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2018, 42, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satteson, E.S.; Brown, B.J.; Nahabedian, M.Y. Nipple-Areolar Complex Reconstruction and Patient Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gland Surg. 2017, 6, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.; Cassisi, J.E.; Dvorak, R.D.; Decker, V.; Becker, S. Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perceptions of Mastectomy Reconstruction: A Comparative Analysis of Medical Tattooing Impact on Aesthetics. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 49, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965; ISBN 978-1-4008-7613-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, T.F.; Labarge, A.S. Development of the Appearance Schemas Inventory: A New Cognitive Body-Image Assessment. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1996, 20, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-9829983-2-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraes, E.F.R.; Durand, P.; Morisada, M.; Scomacao, I.; Duraes, L.C.; De Sousa, J.B.; Abedi, N.; Djohan, R.S.; Bernard, S.; Moreira, A.; et al. A Novel Validated Breast Aesthetic Scale. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2022, 149, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, K.; Radotra, I.; Khanna, A. The CQC’s Recommendations on Psychological Assessment for Cosmetic Surgery Patients: Will They Improve the Patient’s Journey? A Review of Current Practice in the UK Based on a Survey of 71 Plastic Surgeons. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2021, 74, 2392–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Apovian, C.; Brethauer, S.; Garvey, W.T.; Joffe, A.M.; Kim, J.; Kushner, R.F.; Lindquist, R.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Seger, J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutrition, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of Patients Undergoing Bariatric Procedures—2019 Update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 175–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race or Ethnic Identification | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 0.2 |

| Asian or Asian American | 52 | 8.8 |

| Black or African American | 35 | 5.9 |

| White | 327 | 55.5 |

| Hispanic, Latina, or Spanish Origin | 138 | 23.4 |

| Multiracial | 36 | 6.1 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 427 | 72.5 |

| Homosexual | 12 | 2.0 |

| Bisexual | 111 | 18.8 |

| Other | 25 | 4.2 |

| Prefer not to say | 14 | 2.4 |

| Biological Sex | ||

| Female | 589 | 100 |

| Male | 0 | 0 |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Female | 588 | 99.8 |

| Male | 1 | 0.2 |

| Highest Level of Education/Degree | ||

| High School Graduate (diploma or equiv.) | 198 | 33.6 |

| Some college but no degree | 231 | 39.2 |

| Associates degree in college | 142 | 24.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree in college | 18 | 3.1 |

| Instructions: The following questions assess self-satisfaction regarding the breasts and body. Please read each statement carefully and decide how it applies to you. When answering, consider how you have been feeling over the past month. | |

|---|---|

| 1. | I am happy with the position of my nipple and areola complex. |

| 2. | I am happy with the shape of my nipple and areola complex. |

| 3. | I am happy with the color of my nipple and areola complex. |

| 4. | I am satisfied with the size of my breast. |

| 5. | I feel comfortable when others see my breasts. |

| 6. | The appearance of my breast could disturb others. |

| 7. | I feel that people are looking at my chest. |

| 8. | I need to be reassured about the appearance of my bust. |

| 9. | I would keep my chest covered during sexual intimacy. |

| 10. | I think my breasts appear uneven to each other. |

| 11. | I feel people can tell my breasts are not normal. |

| 12. | I think about my breasts. |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I am happy with the position of my nipple and areola complex. | 0.800 | 0.081 |

| 2. I am happy with the shape of my nipple and areola complex. | 0.886 | −0.001 |

| 3. I am happy with the color of my nipple and areola complex. | 0.744 | −0.087 |

| 4. I am satisfied with the size of my breast. | 0.212 | 0.559 |

| 8. I need to be reassured about the appearance of my bust. | −0.013 | 0.726 |

| 9. I would keep my chest covered during sexual intimacy. | 0.167 | 0.434 |

| 10. I think my breasts appear uneven to each other. | 0.161 | 0.338 |

| 11. I feel people can tell my breasts are not normal. | 0.145 | 0.454 |

| 12. I think about my breasts. | −0.010 | 0.583 |

| Factor 1: Nipple–Areola Satisfaction | |

| Item 1 | I am happy with the position of my nipple and areola complex. |

| Item 2 | I am happy with the shape of my nipple and areola complex. |

| Item 3 | I am happy with the color of my nipple and areola complex. |

| Factor 2: General Breast Satisfaction | |

| Item 4 | I am satisfied with the size of my breast. |

| Item 8 | I need to be reassured about the appearance of my bust. |

| Item 9 | I would keep my chest covered during sexual intimacy. |

| Item 10 | I think my breasts appear uneven to each other. |

| Item 11 | I feel people can tell my breasts are not normal. |

| Item 12 | I think about my breasts. |

| BACS Total | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASI-R | 0.297 ** | 0.095 * | 0.353 ** |

| RSE | −0.349 ** | −0.260 ** | −0.320 ** |

| PHQ-9 | 0.237 ** | 0.162 ** | 0.227 ** |

| GAD-7 | 0.228 ** | 0.097 * | 0.255 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gofman, S.; Cassisi, J.E.; Proctor, M.; Paulson, D.; Decker, V. Development of a Screening Measure to Identify Breast Appearance Dissatisfaction in Women. J. Aesthetic Med. 2025, 1, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020007

Gofman S, Cassisi JE, Proctor M, Paulson D, Decker V. Development of a Screening Measure to Identify Breast Appearance Dissatisfaction in Women. Journal of Aesthetic Medicine. 2025; 1(2):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020007

Chicago/Turabian StyleGofman, Sivanne, Jeffrey E. Cassisi, Miranda Proctor, Daniel Paulson, and Veronica Decker. 2025. "Development of a Screening Measure to Identify Breast Appearance Dissatisfaction in Women" Journal of Aesthetic Medicine 1, no. 2: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020007

APA StyleGofman, S., Cassisi, J. E., Proctor, M., Paulson, D., & Decker, V. (2025). Development of a Screening Measure to Identify Breast Appearance Dissatisfaction in Women. Journal of Aesthetic Medicine, 1(2), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jaestheticmed1020007