Abstract

Soil moisture is an essential environmental parameter affecting hydrological cycles, agricultural productivity, and climate systems. Conventional in situ measurements are precise but do not provide the spatiotemporal coverage for large applications. This research provides an extensive framework for estimating and mapping surface soil moisture by integrating Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data with machine learning in the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud platform. The study area is the agricultural region of Perambalur district in Tamil Nadu State, India. The research took place between September 2018 and January 2019. The dual-polarized (VV and VH) Sentinel-1 C-band images were collected in tandem with ground truth soil moisture data collected through the gravimetric method. A set of SAR indices and engineered features were extracted from the backscattering coefficients (σ°). A random forest (RF) machine learning model was used in this study to estimate soil moisture. The RF model incorporating the complete set of engineered features showed a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.694 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.823 (Soil moisture %). The complete processing and modeling workflow was encapsulated in the GEE-based software tool (version 1) providing an accessible, user-friendly platform for generating near-real-time maps of soil moisture. This research proves that the combination of Sentinel-1 data with clever machine-learning algorithms in the GEE cloud platform provides a scalable, efficient, and potent tool for operational soil moisture mapping serving applications in precision agriculture and in the management of the water resource.

1. Introduction

Soil moisture lies at the root of the terrestrial water, energy, and carbon balances. The soil moisture held in the voids among the soil constituents controls the partitioning of received precipitates into runoff and infiltration, controls the rate of evapotranspiration, and has a direct effect on crop growth and agricultural productivity [1,2,3,4,5]. Accurate information on soil moisture at different spatial and time scales is therefore necessary for many applications like the forecasting of droughts and floods, irrigation scheduling, climate simulation, and ecophysiological studies [1,4,5]. The relation between crop condition and soil moisture is simple and profound; below-optimal moisture causes water stress and reduced productivity, while excessive moisture causes root damage and loss of nutrients. This relation forms the cornerstone of precision farming, which aims at maximizing inputs like water and fertilizer in tandem with field conditions in real time.

Traditional techniques like the gravimetric method, time-domain reflectometry (TDR), and neutron probes give highly precise point measurements [6,7]. The in situ methods, though precise and spatially dense, require much more labor and are spatially sparse, making them unsuitable for repeated assessments across large and heterogeneous areas [8,9]. The remote sensing technologies then proved to be the much-needed alternative with the capacity to systematically assess surface soil moisture across large areas [9,10]. Of the many remote sensing approaches, active microwave remote sensing with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) is uniquely the best-suited method [9,10] to this task. Unlike the optical sensors, the SAR systems can be used during the day or at night, and the systems remain minimally affected by atmospheric interference like clouds and fogs, thus allowing for steady data acquisition [10,11].

The European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-1 mission, belonging to the Copernicus program, has transformed Earth observation with the C-band SAR sensor by delivering free, open, and permanent data at high spatial (up to 10 m) and temporal (6–12 days) resolution [10,11,12]. The backscattered signal (σ°) observed by SAR significantly depends on the target surface’s dielectric characteristics, which for bare or sparse vegetation-covered soil are essentially controlled by its moisture content [9,13]. Sentinel-1’s dual polarization (VV and VH) provides some very useful complementary information. The co-polarized backscattering (VV) is observed to be more sensitive to surface scattering and then more directly connected to soil moisture, whereas the cross-polarized backscattering (VH) is more affected by the volume scattering inside the vegetation canopies in order to better quantify the surface status [13,14,15].

Several methods have been proposed for the retrieval of soil moisture in the SAR data, which vary from simple indices-based techniques, empirical and semi-empirical models, to intricate physical models and machine learning techniques [9,13,16,17]. Some polarization-based indices have also been developed to eliminate geometric and sensor effects to enhance the robustness of the soil moisture retrievals. A few of them are the differential power detection difference (DPDD), the normalized difference polarization index (NDPoII), polarization ratios (VH/VV and VV/VH), polarization differences (VH–VV and VV–VH), the polarization product (VH × VV), sum (VV + VH), and the volume-dominant difference polarization index (VDDPI) [16,17,18]. The indices attempt to quantify the physical scattering mechanisms related to the soil’s dielectric constant and surface moisture [17,18].

Empirical models, i.e., multiple linear regression (MLR) models, are easy to develop and deploy, specifying statistical relationships between backscatter and ground observations [13,19,20,21,22,23]. They are generally site and time specific in most cases. In recent years, machine-learning algorithms like Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) have gained immense popularity. They can extract complex, nonlinear relationships and integrate many data sources, often providing more steady and accurate estimations. RF, an ensemble-learning algorithm, is notably acclaimed for having strong accuracy and robustness to noise and the ability to deal with large-dimensional data [14,24]. RF has already proved strong potential for modeling nonlinearity between SAR observables and soil moisture observations. RF can potentially utilize many different SAR-derived features (e.g., VV2, VH2, VV × VH, VH/VV, VH–VV) to learn complex scattering-moisture relationships with higher generalizability [17,24,25].

The massive scale of data produced by such missions as Sentinel-1 creates insurmountable challenges for conventional desktop-centric data analysis and processing. Cloud geospatial platforms, and, in particular, Google Earth Engine (GEE), have become a game-changing answer. GEE encompasses the multi-petabyte inventory of public satellite imagery and offers planetary-scale computing infrastructure, enabling the analysis of extensive datasets on the fly without having to resort to local storage or high-performance computing infrastructure [26,27]. This has made Earth observation data more democratized and has made it feasible to create operational, near-real-time surveillance applications. GEE offers public access to Sentinel-1 archives, application program interface (APIs) for regression modeling, and interactive visualization tools, removing the necessity for local high-performance infrastructure [26,27,28,29]. The integration of empirical, index-based, and RF models within GEE makes it feasible to monitor soil moisture in near real time across agricultural areas [26,27,30,31].

The study aims at developing and validating a comprehensive framework for estimating soil moisture by fusing Sentinel-1 SAR observations with in situ gauges and data-intelligence (RF) models [17,24]. The significant activity is to encapsulate the framework in an editable GEE app in such a way that it becomes a highly accessible and scalable tool for monitoring soil moisture patterns in the agricultural region of Perambalur in India [17,25].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

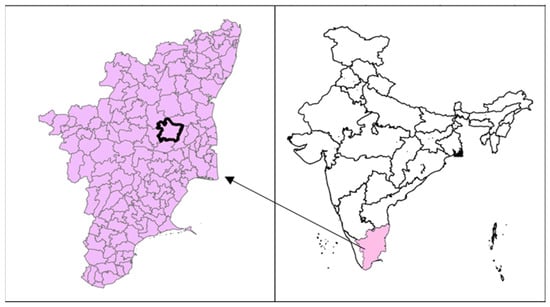

The research area fell within the Perambalur district in the north-central Tamil Nadu region of India, within 10°54′–11°30′ latitude N and 78°36′–79°30′ E longitude (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The district spans about 1,756 km2 and features semi-arid tropical conditions with an average rainfall of 908 mm annually, falling majorly in the October–December period during the north-east monsoon. The area’s topography is flat to gentle undulation with an elevation between 100 m and 200 m above the mean sea level. The dominant soil type is red loam and clay loam with moderate drainage and effective moisture retention, situations best suited for dryland crops like maize, sugarcane, groundnut, and millets. The district experiences reoccurring drought stress following variability in the rainfall regime and is thus well-suited for the analysis of SAR-based soil moisture retrieval. The in situ sampling sites for this research were spaced across the district’s representative agricultural fields (Figure 1). The soil samples were sampled in tandem with Sentinel-1 satellite passage to ensure coincidence between in situ and satellite observations in terms of time.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of the study area. (Left) Perambalur district highlighted within Tamil Nadu, India (Right).

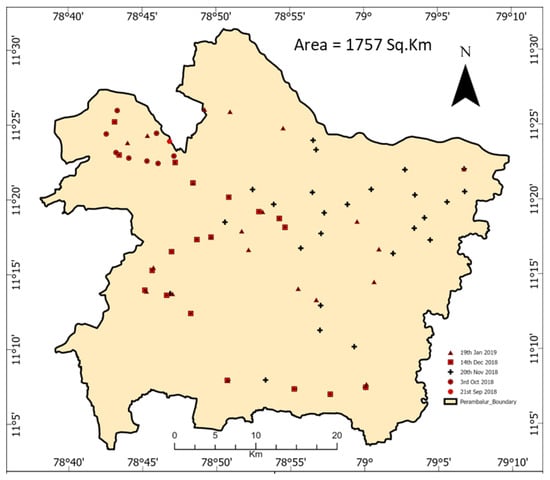

Figure 2.

A detailed map of the district showing the distribution of in situ sampling sites for different dates between September 2018 and January 2019.

2.2. Data Acquisition: In Situ and Satellite

In Situ Data: Ground truth soil moisture data has been collected during the field campaigns in coincidence with Sentinel-1 satellite overpasses on the following days: 21 September 2018, 3 October 2018, 20 November 2018, 14 December 2018, and 19 January 2019. Soil samples in the top 10 cm at several such sampling stations in the district have been collected. The volumetric soil moisture content has been measured by the standard method of gravimetry. The fresh samples were weighed and then dried in the oven at 105 °C for 24 h and reweighed to compute the volumetric soil moisture (θ) . Monthly means were calculated at the sampling date and then matched with the co-registered observations of the SAR. Figure 2 shows the sites of the sampling across the Perambalur district.

Satellite Data: Sentinel-1A C-band (5.405 GHz) SAR data with the interferometric wide (IW) swath mode were downloaded from the Copernicus Open Access Hub during the following five dates which coincided with field campaign dates: 21 September, 3 October, 20 November, 14 December 2018, and 31 January 2019. The Ground Range Detected (GRD) data product with dual polarization (VV and VH) at 10 m spatial resolution was used.

2.3. Preprocessing of SAR

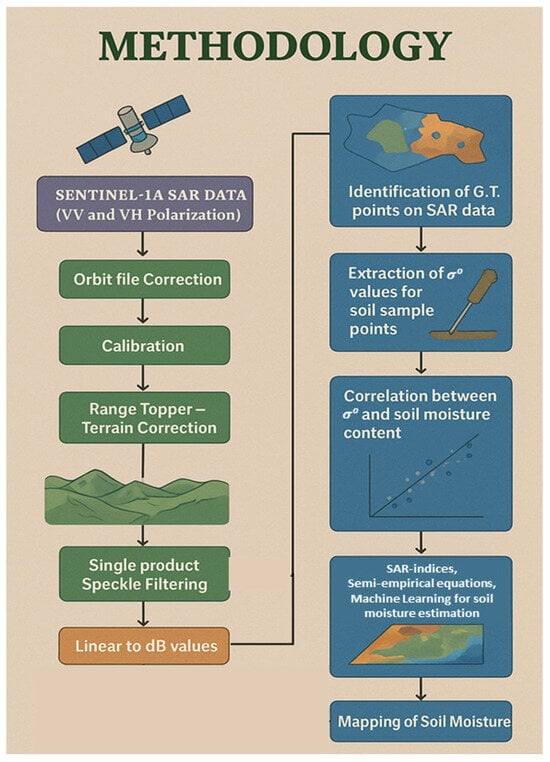

All Sentinel-1 GRD scenes were pre-processed with the ESA Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP) toolbox to convert the raw data to calibrated, georeferenced backscattering coefficients (σ°) [10,11,12,17]. The standardized workflow (see Figure 3) involved the following steps: Apply Orbit File: To update satellite position and velocity information for precise geolocation. Thermal Noise Removal: To reduce noise artifacts, primarily in the cross-polarized (VH) channel. Radiometric Calibration: To convert pixel observations from digital numbers to the physically meaningful σ° quantities in linear terms. Speckle Filtering: Use of a 3 × 3-windowed Lee filter to reduce the inherent granular noise (speckle) in the SAR imagery [9,13,17]. Range Doppler Terrain Correction: Correction for geometric deformation in relation to the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) 30m Digital Elevation Model (DEM), aiming to achieve precise geographic registration. Conversion to Decibels (dB): The linear σ° quantities were converted to the logarithmic scale of decibels (dB) with the following formula: where DN is the calibrated strength of the pixel and A is the calibrating factor [9,11].

Figure 3.

The methodological workflow adopted in this study, from Sentinel-1 data pre-processing to model development and the generation of soil moisture maps.

2.4. Estimating Soil Moisture

2.4.1. Feature Engineering

To provide comprehensive information to the machine learning model, a variety of SAR-based indices and engineered features were calculated from the VV and VH backscatter values. These indices reduce the influence of topography and surface roughness and emphasize dielectric contrast caused by soil wetness. The SAR-based indices enhance sensitivity to different surface characteristics. Table 1 shows all the indices used in this work along with their benefits. These indices were also features used for training the machine learning approach for estimating soil moisture from the SAR dataset. The primary features used were polarization ratios and differences: VH/VV and VH-VV, sensitive to vegetation structure and surface roughness. Mathematical combinations: VV × VH, VV + VH, VV2, VH2. Normalized difference polarization index (ND-Poll): (VV−VH)/(VV + VH), which helps in normalizing the data and reduce topographic effects. Differential power detection (DPDD): VV + VH, sensitive to changes in dielectric properties [16,17,18]. Volume-dominant difference polarization index (VDDPI): (VV + VH)/VV, used to assess the contribution of volume scattering.

Table 1.

SAR-based indices derived from the VV and VH polarization channels, which were calculated from SAR dataset and used as input features for the Random Forest model.

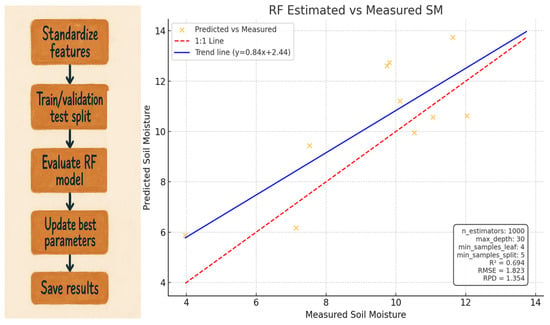

2.4.2. Random Forest (RF) Regression

A Random Forest regressor, which is a strong ensemble machine-learning algorithm, was then formulated as the more sophisticated alternative. RF creates many individual decision trees and makes collective decisions with their outputs, which reduces overfitting and enhances generalizability. The model was trained on both direct and engineered SAR features: {VV, VH, VV2, VH2, VV × VH, VH/VV, VV/VH, VH–VV, VV-VH, VV + VH, DPDD, NDPoII, and VDDPI}. RF creates an ensemble of decision trees in which the conclusive output is the average across-trees output [21,22]. The number of trees (n = 500) and maximum depth were optimized with ten-fold cross-validation on the following hyperparameters. The model was evaluated with in situ soil moisture observations as ground truth [23]. Statistic metrics—R2, RMSE, and mean absolute error (MAE)—were calculated for each method (MLR, index-based, and RF).

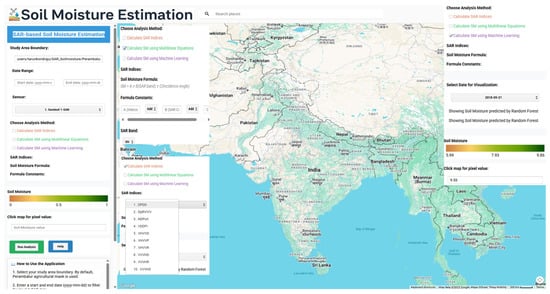

2.5. Google Earth Engine (GEE) Tool Development

A key outcome of this study was the translation of the analysis into an operational tool within GEE [26,27,28,29]. A web-based application was developed using GEE’s JavaScript API. The application integrates the Sentinel-1 data archive, SAR indices calculations, MLR equations and trained RF model, based soil moisture estimation. It allows users to define an area of interest, a date range, and analysis methodology, and the tool automatically processes the relevant SAR imagery and applies the specific soil moisture model to generate and display a soil moisture map in near real time.

3. Results

3.1. In Situ Soil Moisture and SAR Backscatter Dynamics

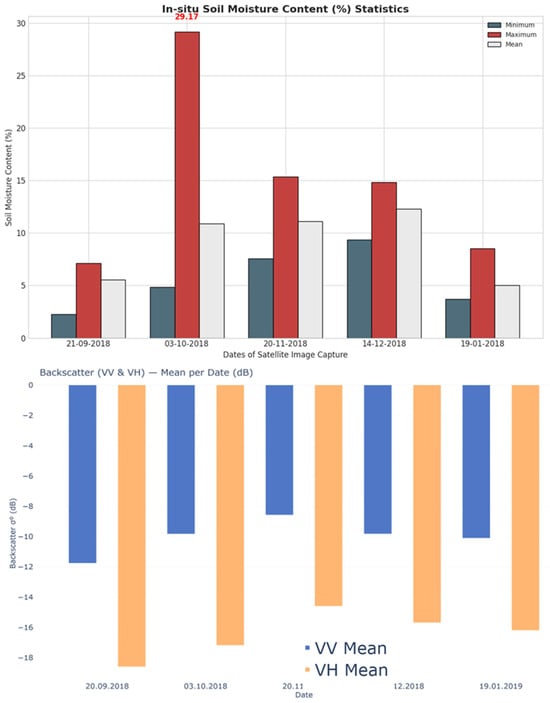

The in situ measured soil moisture values showed high temporal variability between September 2018 and January 2019 (Figure 4 (top)). The least soil moisture was found on 21 September 2018 at Arumbavur (2.27%) and Poolambadi (3.00%), characteristic of post-monsoon dryness. The soil moisture grew rapidly in October 2018, varying between 4.85% and 29.17% at the sampling stations. November 2018 exhibited moderate values, where most samples were greater than 10%, while December 2018 exhibited high but constant values. The minimum mean moisture (≈5.04%) with minimum variation occurred in January 2019, indicating surface drying during post-monsoon conditions.

Figure 4.

Statistical summary (minimum, maximum, and mean) of in situ soil moisture content (%) for the five sampling dates (Top) and temporal variation in Sentinel-1 backscatter statistics (σ° in dB) for VV and VH polarizations over the study period (Bottom).

Backscattering coefficients (σo for both polarizations exhibited similar seasonal variation (Figure 4 (bottom)). VV polarization ranged from −12 dB to −8 dB, and VH ranged from −18 dB to −14 dB. Both indicated greater σo from September to December and then, in January, a sharp reduction. The VV channel consistently indicated higher σo magnitudes, reflecting higher surface scattering than VH, namely, volume vegetation-affected [14,15,17,24]. This is indicative of the sensitivity of the C-band signal to temporal changes in surface moisture.

3.2. Random Forest (RF) Model Performance

Total observed data was split into testing and training data with 30 to 70% ratio. The RF regression algorithm was trained using training data and tested with the test data. The Random Forest (RF) model, which integrated all the engineered SAR features with SAR indices, performed significantly better. With these enhancements, the RF model predicted R2 = 0.694, RMSE = 1.823, and ratio of performance to deviation (RPD) = 1.354 with final hyperparameter settings as n_estimators = 1000, max_depth = 30, min_samples_leaf = 4, and min_samples_split = 5 [21,22,23,24,25]. The ranking of feature importance showed that VV-related predictors (VV and VV × VH) contributed the most to model performance, followed by VH/VV and VH–VV ratios [17,24,25]. Figure 5 shows the process of RF model training and validation, along with a scatter plot illustrating the high concordance of predictions by the RF model with measured ground truth values, having points tightly clustered around the 1:1 perfect agreement line. The trendline shows that though the RF model performs better, it slightly overestimates the target.

Figure 5.

Performance of the Random Forest model, showing the correlation between predicted and measured soil moisture.

3.3. Model Evaluation

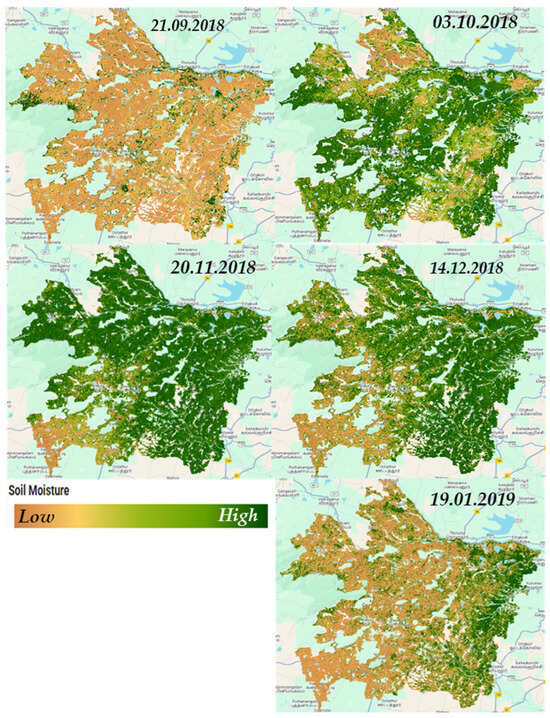

The RF algorithm can derive nonlinear relationships between SAR observables and soil moisture. Table 2 shows the performance of the RF model. From the table, the model performance is acceptable, as the R2 is 0.65, RMSE is 1.823 (soil moisture in %), and the MAE is 2.36 (soil moisture in %). This validated model was later used to estimate the soil moisture from the SAR datasets, and the results are shown in Figure 6. The moisture maps reflect the temporal variations in the soil moisture estimate in the Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu for the dates considered. The soil moisture varies from light brown to dark green, depicting the increase from less soil moisture to more soil moisture. Additionally, these maps show only the masked area with bare soil only. The vegetation area was masked from the satellite imagery with an agriculture mask generated using multispectral optical satellite Sentinel-2 (S2) and NDVI vegetation index. The soil moisture maps successfully showed spatial gradients, where the values were more abundant in low-lying agriculture areas and less so over upland regions. The maps showed the spatial heterogeneity and temporal soil moisture evolution from wet (October–November) to dry (January) was obviously observed in the GEE interface. The cloud-based feature of the tool allowed real-time retrieval and visualization without local computation, from wetness in October to general dryness in January.

Table 2.

Shows the average performance metrics of RF approach.

Figure 6.

Shows the soil moisture spatial maps estimated using the RF model incorporated into GEE. Each image is labeled using the date of the image. A color gradient legend is provided to indicate the soil moisture content in each image. Light brown and yellow indicate lower soil moisture content in the soil and the greener shaded indicate higher soil moisture content in the soil.

3.4. Spatial Soil Moisture Mapping and GEE Application

Since the RF model is now integrated into GEE, an application with a user-friendly user interface (UI) was developed to utilize the RF model for estimating soil moisture for a particular region based on user inputs through GEE-based cloud computing. A GEE application named the soil moisture estimation tool (SMET) was developed for on-demand soil moisture mapping and can be accessed from https://ee-tarunkondraju.projects.earthengine.app/view/soil-moisture-estimation-tool (accessed on 26 November 2025). The user interface of the application can be seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Shows the UI for the GEE application used to estimate soil moisture from Sentinel-1 SAR imagery. The image also indicates various options and panels available to the user for calculating soil moisture: indices, multiple linear regression, and the RF approach.

Along with the RF model, the application hosts several indices (see Table 2) that the user can use to assess the soil moisture or study the surface from the SAR dataset. Further, the application also offers multiple linear regression-based soil moisture estimation options. For the same study area [32] several date-specific MLR models were developed. These models establish a simple linear relationship between the measured soil moisture (dependent variable) and the SAR backscatter (σ°) and the sensor’s local incidence angle (independent variables). A linear model was formulated to estimate soil moisture (SM) from σ0 and incidence angle (θi): , where a is the intercept and b1, b2, and b3 are the regression coefficients optimized using least-squares fitting. The formula structure was incorporated into the application. So, users can use this option if they already have an equation to calculate soil moisture from the SAR dataset using only VV and VH polarization and the inclination angle, then they can use this option to understand the spatial variability of soil moisture or on a specific date.

The application allows the user to select a location using the GEE asset and a date range by providing the start and end dates. Then, the user needs to choose one of the available processes for estimating the soil moisture from SAR dataset. After the selection, the user can click on the run analysis button. The application will collect all the images in that area of interest between the start and the end date. These images will be sorted as per the date and will be shown in the data selection drop down menu. Once the user selects the date, the corresponding soil moisture image will be displayed on the Google maps along with the boundary shapefile. The associated legend with the minimum and maximum soil moisture values observed across the area will be displayed. The current displayed image can be clicked to reveal the soil moisture at that particular pixel in the dedicated text box. Further, the displayed image can be downloaded if it is less than 32 MB in size.

4. Discussion

This work successfully developed and validated a robust soil moisture estimation algorithm from Sentinel-1 data, culminating in an operational GEE-based tool. The findings of this study offer several key conclusions about the application of SAR remote sensing to crop monitoring. The soil moisture estimation through VV has out performed soil moisture estimation using VH polarization, and is consistent with the radar remote sensing physics and most previous research studies [9,13,14,15,17]. VV-polarized waves engage primarily through surface scattering, which is highly sensitive to the topsoil layer’s dielectric constant, a variable that directly represents moisture content itself. VH-polarized backscatter is dominated by volume scattering from vegetation and surface multiple scattering, which can suppress the soil moisture signal. Our results confirm that for moderately to lightly vegetated agricultural croplands, VV polarization is the preferred channel for direct soil moisture estimation. Temporal observations confirmed the impact of rainfall variability; October 2018 exhibited maximum soil moisture variation (approx. 7.94% standard deviation) following high-intensity rainfall events, and January 2019 illustrated a dry equilibrium phase. These processes confirm the physical correspondence between surface dielectric properties and SAR backscatter response. The Random Forest model further enhanced performance by incorporating nonlinear interactions among features, reducing error propagation present in purely empirical methods [19,20,21,22,23,28].

These results emphasize that Sentinel-1 SAR observations coupled with engineered polarization-based features and Random Forest regression can estimate surface soil moisture effectively in semi-arid agricultural regions. The RF model’s performance (R2 = 0.694) can be attributed to its ability to recognize complex, nonlinear relationships and to effectively combine information from a broad range of input features. Parameters such as vegetation water content, leaf area index, and surface roughness introduce nonlinearity to backscatter-soil moisture relations. Engineered indices such as ratios reduce the RF model to partially decompose the effects of confusion, leading to better estimation. The RF model, having been learned with more varied sets of features and conditions, represents a more robust and portable solution. The development of the GEE application represents a significant step forward in making this type of research more operationalizable.

The standard model for downloading, storing, and processing terabytes of satellite data represents a critical bottleneck limiting the practical application of remote sensing for decision making. By employing the GEE platform, all such workflow is automated and executed on the cloud with results generated within seconds through a web browser. Such “democratization” of satellite data analysis can provide stakeholders such as agricultural extension agencies, water resource managers, and even farmers themselves with timely data-based information for activities like irrigation scheduling and drought analysis [26,27,28,29,30,31]. The ability to generate maps in near real-time is a paradigm shift from after-the-event analysis to real-time control. Despite the promising results, this work is not without limitations.

The empirical nature of the RF model makes it still dependent on the range of conditions within the training data. Its performance can degrade if it is applied in regions that have highly varied soil types, plant cover, or climate without local calibration. Furthermore, C-band SAR penetration is minimal in densely vegetated canopy layers, and accuracy will decrease in highly forested areas or cropped fields with tightly spaced mature crops. Subsequent research can focus on improving the transferability of models by employing more and geographically spread-out training datasets. Integration of data, combining Sentinel-1 SAR data with Sentinel-2 optical data (to improve the description of vegetation) and thermal data (to provide surface temperature estimation) would potentially increase the accuracy of the model. Exploration of more advanced deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can also unveil new potential by automatically learning spatial features from the imagery.

5. Conclusions

This research effectively demonstrated an end-to-end and scalable processing pipeline for estimating and tracking surface soil moisture from Sentinel-1 SAR images in the Google Earth Engine platform. It was confirmed that VV polarization is more sensitive to soil moisture than VH polarization. A Random Forest machine-learning algorithm, trained on a collection of engineered SAR features and indices, demonstrated a high predictive power (R2 = 0.694). The integration of this model into a readily available GEE application introduces a scientific process that entails managing complexity to the level of an actionable tool for near real-time environmental monitoring. This paper recognizes the tremendous potential for synergy between open-access satellite imagery, advanced machine learning, and cloud computing in providing actionable intelligence for sustainable agriculture and water resource management, unlocking the door to data-driven decision-making at scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.T.K. and S.R.; methodology, T.T.K.; software, R.N.S.; validation, T.T.K. and R.R.; formal analysis, T.T.K. and R.G.R.; investigation, R.G.R.; resources, T.T.K., R.G.R. and A.B.; data curation, R.G.R. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.K.; writing—review and editing, T.T.K. and R.N.S.; visualization, T.T.K.; supervision, R.N.S.; project administration, R.N.S.; funding acquisition, R.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results summarized in the manuscript were achieved as part of the research project “Network Program on Precision Agriculture (NePPA)”, which is funded by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), India.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Corti, T.; Davin, E.L.; Hirschi, M.; Jaeger, E.B.; Lehner, I.; Orlowsky, B.; Teuling, A.J. Investigating soil moisture–climate interactions in a changing climate: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2010, 99, 125–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobriyal, P.; Qureshi, A.; Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A. A review of the methods for monitoring soil moisture. J. Hydrol. 2012, 458, 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken, H.; Huisman, J.A.; Bogena, H.; Vanderborght, J.; Vrugt, J.A.; Hopmans, J.W. On the value of soil moisture meas-urements in vadose zone hydrology: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, W00D06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robock, A.; Vinnikov, K.Y.; Schlosser, C.A.; Speranskaya, N.A.; Entin, J.K. The global soil moisture data bank. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 81, 1281–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Blöschl, G.; Pampaloni, P.; Calvet, J.C.; Bizzarri, B.; Wigneron, J.P.; Kerr, Y. Operational readiness of microwave remote sensing of soil moisture. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, G.C.; Davis, J.L.; Annan, A.P. Electromagnetic determination of soil water content: Measurements in coaxial trans-mission lines. Water Resour. Res. 2003, 16, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, A.W.; Grayson, R.B.; Blöschl, G. Scaling of soil moisture: A hydrologic perspective. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2002, 30, 149–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, E.G.; Jackson, T.J.; Lakshmi, V.; Chan, T.K.; Nghiem, S.V. Soil moisture retrieval from AMSR-E. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaby, F.T.; Moore, R.K.; Fung, A.K. Microwave Remote Sensing: Active and Passive, Vol. 2: Radar Remote Sensing and Surface Scattering and Emission Theory; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, R.; Snoeij, P.; Geudtner, D.; Bibby, D.; Davidson, M.; Attema, E.; Potin, P.; Rommen, B.; Floury, N.; Brown, M.; et al. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, N.; Zribi, M.; Paloscia, S.; Verhoest, N.E.C.; Lievens, H.; Van Der Velde, R.; Panciera, R.; Bouvet, A.; De Lannoy, G. An overview of the soil moisture products from the Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 596. [Google Scholar]

- Hajnsek, I.; Pottier, E.; Cloude, S.R. Inversion of surface parameters from polarimetric SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2003, 41, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zribi, M.; Baghdadi, N.; Holah, N.; Fafin, O. New methodology for soil surface moisture estimation from C-band radar data. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W08410. [Google Scholar]

- Attema, E.P.W.; Ulaby, F.T. Vegetation modeled as a water cloud. Radio Sci. 1978, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; He, B.; Li, X.; Zeng, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. First assessment of Sentinel-1A data for soil moisture retrieval using a coupled water cloud model and advanced integral equation model over the central Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 714. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska-Zielinska, K.; Musial, J.; Malinska, A.; Budzynska, M.; Gurdak, R.; Kiryla, W.; Bartold, M.; Grzybowski, P. Soil moisture in wetlands—Estimation by a combination of the C-band Sentinel-1 and optical data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Paloscia, S.; Pettinato, S.; Santi, E.; Notarnicola, C.; Pasolli, L.; Reppucci, A. Soil moisture mapping using Sentinel-1 images: Algorithm and preliminary validation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 134, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.; Le, N.; Ha, N.; Nguyen, L.; Tran, D.; Nguyen, C.; Bui, D.T. A new approach for soil moisture estimation using Sentinel-1 SAR data and a Random Forest algorithm. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3338. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Han, D.; Ramirez, M.R.; Islam, T. Machine learning techniques for downscaling SMOS satellite soil moisture using MODIS land surface temperature for hydrological application. Water Resour. Manag. 2013, 27, 3127–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.S.; Alonso, L.; Moreno, J.F.; Mateo, M.P. A multi-resolution, multi-temporal approach for estimating fractional vegetation cover with remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountrakis, G.; Im, J.; Ogole, C. Support vector machines in remote sensing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiu, M.; Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 114, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, A.; De Lannoy, G.; Albergel, C.; Vreugdenhil, M.; Wagner, W.; Dorigo, W. Validation of the ESA CCI soil moisture product in the U.S. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 194, 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Zribi, M.; Escorihuela, M.J.; Baghdadi, N.; Seguin, B. Determination of soil moisture from C-band radar data. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 32, 130–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Kakooei, M.; Moghimi, A.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Moghaddam, S.H.A.; Mahdavi, S.; Ghahremanloo, M.; Parsian, S.; et al. Google Earth Engine Cloud Computing Platform for Remote Sensing Big Data Appli-cations: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5326–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimple, U.; Sitole, A.; Patel, A.; Simon, B. Google Earth Engine based analysis for agricultural drought monitoring in Bun-delkhand region, India. Geomat. Nat. Haz. Risk 2021, 12, 166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, T.; Jagdhuber, T.; Piles, M.; Kainulainen, J.; Karbou, F.; Ikonen, J. Towards a global soil moisture product from Sen-tinel-1: A deep learning approach. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Steele-Dunne, S.C.; McNairn, H.; Monsivais-Huertero, A.; Judge, J.; Liu, P.W.; Papathanassiou, K. Radar remote sensing of agricultural canopies: A review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2017, 10, 2249–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazirh, A.; Merlin, O.; Er-Raki, S.; Gao, Q.; Rivalland, V.; Malbeteau, Y.; Khabba, S.; Escorihuela, M.J. An operational soil moisture mapping algorithm at high resolution over agricultural areas using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1811. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, S.; Ramasamy, J.; Ramalingam, K.; Sivakumar, K.; Sellaperumal, P.; Deepagaran, G. Estimation of soil moisture from Sentinel-1A synthetic aperture radar (SAR) in Perambalur district of Tamil Nadu. Pharma Innov. J. 2019, 8, 360–362. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).