Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

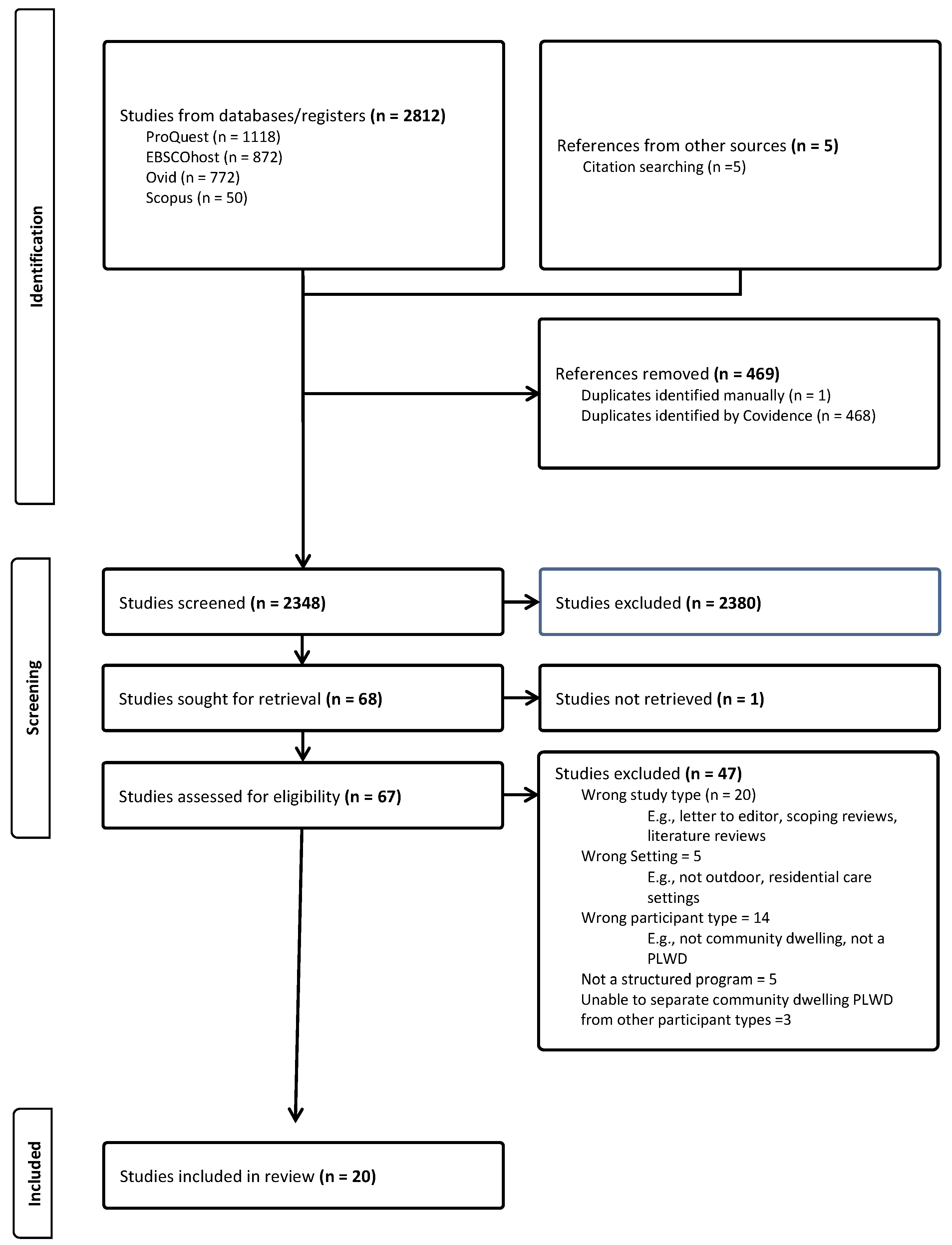

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Research Question

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

2.3. Selecting the Studies

2.4. Extracting and Charting the Data

2.5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Author(s), Year Country | Aim(s) Setting/Context Study Design | Participants | Methodology, Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| de Bruin et al., 2009 [26] Netherlands | Study 1: to inventory the types of activities organized in each type of day care facility and determine the location of the activities organized and the degree of group participation in these different activities. | Study 1: PLWD and older people without dementia; participants characteristics not reported. | Study 1: group level observation, 3.5 to 5 days per facility; average 6 h per facility |

| Study 2: to gain insights into the activities performed by PLWD in both settings by looking at the types and locations of the activities and the physical effort required. 11 GCFs predominately receiving PLWD and older adults without dementia; 12 RDCs located close to the GCFs. Cross-sectional studies. | Study 2: 30 PLWD attending GCF: 5 females, 25 males Age, mean—years: females = 80.4; males = 77 MMSE, mean: females = 19.0; males = 19.4 25 PLWD attending RDC: 18 females, 7 males Age, mean—years: females = 82.9; males = 80.9 MMSE, mean: females = 18.2; males = 20 | Study 2: individual level observation level, 1 or 2 days per person; average 6 h per person. Activity classification: (1) physical effort classification using method of Van Raaij et al. (1990); (2) other classifications completed after observations were completed. | |

| de Bruin et al., 2012 [27] Netherlands | To compare longitudinal change in functional performance in community-dwelling PLWD who attend GCFs or RDCFs. 15 GCFs offering day care to groups of 5 to 15 people per day; 22 RDCFs mostly located in the same region as the GCFs. Observational cohort study. | GCF participants—47 PLWD Cohort A: 5 females, 23 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 77.7 (5.2) Dementia type: n = 10 AD; n = 3 VD; n = 4 Other; n = 11 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD)—years: 3.1 (1.8) MMSE, mean (SD): 19.5 (5.6) n = 2 widowed; n = 26 married or cohabitating Cohort B: 3 females, 10 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 75.4 (7.5) Dementia type: n = 5 AD; n = 1 VD; n = 1 Other; n = 3 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD)—years: 4.7 (2.5) MMSE, mean: 20.2 (7.1) n = 0 widowed; n = 10 married or cohabitating Cohort C: 2 females, 7 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 79.0 (4.6) Dementia type: n = 2 AD; n = 3 VD; n = 0 Other; n = 4 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD)—years: 3.8 (2.1) MMSE, mean (SD): 22.3 (4.3) n = 3 widowed; n = 6 married or cohabitating RDC participants—41 PLWD Cohort A 12 females, 2 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 83.4 (5.8) Dementia type: n = 10 AD; n = 3 VD; n = 4 Other; n = 11 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD)—years: 3.1 (1.8) MMSE, mean (SD): 19.5 (5.6) n = 8 widowed; n = 6 married or cohabitating, Cohort B 7 females, 6 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 82.0 (7.2) Dementia type: n = 5 AD; n = 1 VD; n = 1 Other; n = 3 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD)—years: 2.9 (2.0) MMSE, mean: 21.4 (4.0) n = 7 widowed; n = 6 married or cohabitating, Cohort C 5 females, 9 males: Age, mean (SD)—years: 82.8 (6.6) Dementia type: n = 4 AD; n = 1 VD; n = 1 Other; n = 8 unspecified Dementia duration, mean (SD) -years: 3.1 (1.8) MMSE, mean (SD): 20.6 (5.9) n = 8 widowed; n = 6 married or cohabitating. | (1) Primary caregiver interviews at their homes—at study entry, six- and 12-month follow-up; (2) BADL using Barthel Index; (3) IADL using the IDDLD; (4) co-morbidity; (5) medication use. Analysis: Fisher’s Exact Test, chi square test for independence, Mann–Whitney U test, linear regression |

| de Bruin et al., 2015 [28] Netherlands | To explore the value of day services at GCFs in terms of social participation for PLWD. GCFs. Qualitative descriptive study. | 21 PLWD attending day services at GCFs: 3 females, 18 males Age, mean (SD)—years: 71.0 (7.5) Dementia type (self-report): n = 11 AD; n = 4 VD; n = 2 PD dementia; n = 2 other dementia; n = 2 unknown Years with dementia (self-report), mean (SD): 5.7 (2.6) n = 21 married or living with a partner n = 9 had agricultural background Family caregiver: 18 females, 3 males Age, mean (SD)—years: 68.3 (8.3) ----------------------------------------- 12 PLWD on waiting list for GCFs; 2 females, 10 males Age, mean (SD)—years: 76.1 (9.6) Dementia type (self-report): n = 4 AD; n = 4 VD; n = 2 other dementia; n = 2 unknown Years with dementia (self-report), mean (SD): 6.8 (8.3) 11 married/living with partner, 1 living with other family member n = 6 had an agricultural background Family caregiver: 10 females, 2 males Age, mean (SD): 72.5 years (8.9) | Semi-structured interviews with dyads of PLWD living at home and family caregivers. Analysis: Framework analysis method |

| de Bruin et al., 2021 [29] Netherlands | To understand (1) the motivation of PLWD and family carers to choose nature-based ADSs in urban areas; (2) the value of nature-based ADSs in urban areas in terms of the health and well-being of PLWD and family carers from different perspectives, i.e., PLWD, family carers, providers of nature-based ADSs in urban areas. Nature-based ADSs in urban areas in different regions of the Netherlands. Qualitative study. | 21 PLWD; 8 females, 13 males Age, range—years: 51 to 90 Type of ADS PLWD attending: n = 15 social entrepreneur; n = 2 nursing home; n = 1 social care organization; n = 3 hybrid type 18 family carers: 16 females, 2 males Age, range—years: 46 to 82 Relationship with PLWD: n = 9 wife, n = 1 ex-wife, n = 1 partner, n = 5 daughter, n = 1 husband, n = 1 brother ----------------------------------------- 15 providers of nature based ADSs. Provider types: (1) n = 7 social entrepreneur in a green environment, e.g., city farm, city garden, park; n = 2 South region, n = 3 Middle region, n = 2 North region. (2) n = 3 nursing home opening up its garden to community-dwelling PLWD living; n = 1 i Middle region, n = 2 North region. (3) n = 1 social care organization organizing green activities, e.g., green maintenance, children’s farm, or city farm visits and walks in green environments; South region. (4) n = 1 citizen(s) with other agencies, offer ADS in a community garden; Middle region (5) n = 3 hybrid ADS, LTC institution jointly organizes nature-based ADS with other types of partners; n = 1 South region, n = 1 Middle region, n = 1 North region. | 40 to 60 min, face-to-face semi-structured interviews with the following: (1) PLWD and family carers in their homes or at the ADS [dyads; separately]; 2 participants together based on preference; (2) providers at their workplace. Framework analysis method to analyze the data. |

| Ellingsen-Dalskau et al., 2021 [30] Norway | To (1) compare aspects of the care environment between FDCs and RDCs; (2) investigate the types of activities taking place, engagement; physical effort, social interaction and mood. 10 FDC services at ordinary farms in the community with a varying degree of conventional farming activities. 7 RDCs, with their own staff, situated near, or within, residential nursing homes across different regions in Norway. Observational study. | 42 participants from 10 FDCs 46 RDC participants No collection of demographic information. | (1) participant observation in random order for 1 min, three times per hour, for a total of 4 h (12 observations per participant); (2) MEDLO Analysis: mean percentage, SD, estimate of fixed effect, SE, 95% CI; linear mixed model. |

| Finnanger Garshol et al., 2020 [31] Norway | To investigate: (1) the potential of FDCs as services that can promote physical activity for PLWD by comparing the levels of physical activity between RDC and FDC attendees; (2) levels of physical activity for FDC attendees on the days they are at the farm and the days they are not. 15 FDC services across all of Norway; and 23 MDC in the south-eastern part of Norway. Secondary analysis of data collected in two separate studies [longitudinal study; cross-sectional study (Olsen et al., 2016)]. | 29 FDC participants: 9 females, 20 males Age, mean (SD)—years: 74 (7.22) 13.8% were living alone 20.7% had a college or university education CDR: 10.3% very mild; 65.5% mild; 20.7% moderate; 3.7% severe 107 RDC participants: 71 females, 36 males Age, mean (SD)—years: 84.3 (8.10) 54.3% were living alone 28.7% had a college or university education CDR: 2.9% very mild; 40.2% mild; 48% moderate; 4.9% severe | Actigraphy, CDR scale and TUG data Analysis: t-test, adjusted linear regression, mixed model regression. |

| Finnanger-Garshol et al., 2022 [32] Norway | In-depth comparison of the emotional well-being of FDC and RDC participants as related to care environment aspects. FDCs situated at commercial farms; RDCs situated at or near nursing homes, with their own staff. Part of a larger project investigating FDCs in Norway. Observational study. | 42 participants from 10 FDCs 46 participants from seven RDCs No demographic information for participants | (1) participant observation in random order for 1 min, three times per hour, for a total of 4 h, 12 observations per participant; (2) MEDLO Analysis: t-test, linear mixed models. |

| Hall et al., 2018 [33] Canada | To assess if and how day program providers could (1) increase client engagement in horticultural activities on both a physical and emotional level by adopting an improved garden design and recreational programming built on client strengths (i.e., interest and past history with gardening); (2) promote client self-determination compared to more traditional and staff-directed day program activities. A 10-week, twice weekly structured horticultural therapy program in the dementia-friendly garden space at McCormick Home [Alzheimer Outreach Services]. Mixed methods | 14 Alzheimer Outreach Services’ clients: 4 females, 10 males Age—years: 61 to 96; average = 84 MMSE: average = 20; range = 8 to 30; Type of dementia: n = 5 AD; n = 3 non-specified dementia; n = 1 FTD; n = 3 VD, n = 1 PD-related dementia; n = 1 unknown diagnosis | (1) DCM Observational Tool; (2) recorded narrative notes underwent thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006); (3) questionnaire, developed by previous director of Alzheimer Outreach Services, mailed to each caregiver to complete for each day their family member attended the garden project. |

| Hassink et al., 2019 [34] Netherlands | To (1) Provide insight into the characteristics of different types of nature-based ADSs in urban areas for PLWD living at home. (2) Explore common and specific challenges for the development and running of different types of nature-based ADSs in urban areas. Nature-based ADSs in urban areas. Two-phase mixed methods study. | 21 representatives of nature-based ADS completed the online survey 17 initiators of nature-based ADS were interviewed | (1) national inventory of nature-based ADSs in urban areas; (2) semi-structured interviews with initiators of the ADSs identified in the first phase. Analysis: Inductive, iterative process (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) |

| Hewitt et al., 2013 [24] England | To (1) identify the possible benefits of a structured group gardening program for people with YOD; (2) identify potential changes in well-being and the mental state of participants and the perceptions of carers; (3) identify useful assessment scales and group activities to inform a larger research project. Two community sites: (1) Thrive Trunkwell Garden Project, Berkshire—a site developed for horticultural therapy for people with physical disabilities, learning difficulties, and older PLWD; (2) Barkham Day Hospital garden—a purpose- designed garden for PLWD, on the grounds of Wokingham Community Hospital, Berkshire. 46 sessions held weekly for 2 h. Each session included a group meeting to socialize and help plan the session; 1 h of structured gardening tasks targeted to each person’s abilities; and, regroup after the gardening to reflect, discuss progress, and promote group belonging. Mixed methods. | 12 PLWD: 8 females, 4 males Age—years: mean = 58.6; range = 43–65 Dementia type: AD n = 9; FTD n = 1; Mixed AD/VD n = 1; DLB, n = 1 | Perceived benefits of the activities were assessed qualitatively using semi-structured interviews with carers and quantitatively with BWBP. |

| Ibsen et al., 2018 [35] Norway | To map available FDCs in Norway and describe services and participants’ care environment. Farms throughout Norway offering day care services to PLWD. Cross-sectional survey. | 32 FDCs: n = 6 providers (face-to-face interviews); n = 26 providers (telephone interviews) | Telephone and face-to-face interviews. |

| Ibsen et al., 2020 [36] Norway | To (1) describe PLWD who attend FDC in Norway; (2) explore whether the characteristics of participants and FDC are associated with QoL. FDC, 25 farms. Cross-sectional design. Study reported on data collected in a larger project (Eriksen et al., 2019). | 94 dyads (PLWD and next of kin): 36 females (38.3%), 58 males (61.7%) Age—years: mean (SD) = 75.8 (8.3); range = 58 to 96 Married/cohabitant, n = 60 (63.8%); Alone (unmarried, divorced, widowed), n = 34 (36.2%) 84.9% had a dementia diagnosis, type not stated MoCA, mean (SD) = 11.5 (6.2) CDR Sum of boxes, mean (SD) = 7.4 (3.2) 54.3% had mild dementia, 26.6% had moderate dementia, 1.1% had severe dementia 38.3% had full awareness of their memory loss | (1) QoL-AD scale; (2) OSS-3; (3) MoCA; (4) CDR; (5) REED; (6) MADRS; (7) RAID-N; (8) NPI; (9) GMHR; (10) EQ-VAS; (11) Physical activity—participants and next of kin were asked about how many days per week participants were physically active for at least 20 min; (12) PSMS; (13) IADL. Analyses: multilevel regression analysis; univariate analysis; multivariate multilevel linear regression |

| Ibsen T.L, & Eriksen S., 2021 [37] Norway | To investigate how PLWD describe attending FDCs in Norway. Five FDC services in different parts of Norway. Qualitative descriptive study. | 10 PLWD: 4 females, 6 males Age—years: 60 to 70, n = 5; 71 to 80, n = 2; 81 to 90, n = 3 7 lived with a partner, 3 lived alone 4 participants had previous experience with farm work | Semi-structured interviews with participants at the farm. Content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman 2004). |

Innes et al., 2024 [38] Canada | To explore the understanding of outdoor-based activities from the perspectives of organizations providing outdoor opportunities, PLWD, and their care partners. Outdoor-based support/programming/ services in three target areas in Southern Ontario. Multiple-methods. | n = 29 organization workers; 22 females, 7 males Age—years: 21–30, n = 2; 31–40, n = 3; 41–50, n = 11; 51–60, n = 7; 61–70, n = 4; 71+, n = 0 Years of Service in Role, Organization—years: <1, n = 3; 1–3, n = 7; 3–5, n = 1; 5–10 years, n = 5; 10+, n = 11; No response, n = 2 21 PLWD * Years Since Diagnosis: <1, n = 2; 1–2, n = 4; 2–3, n = 6; 3+, n = 7; No response, n = 1 14 care partners * 19 older adults * * demographics by group not available | (1) 1–1 interviews; (2) focus groups; (3) walking focus groups. Thematic analysis |

| Morris et al., 2021 [39] England | To present the findings regarding the impact of attending the GLC on self-reported well-being for PLWD and care partners. GLC garden, at the front of the Dementia Hub building, within the campus of the University of Salford. Specific study design not stated. | 4 PLWD, 4 current care partners, 6 former care partners: 11 females, 3 males Age—years: average = 68.5; range = 50 to 87 | (1) Post GLC semi-structured interviews (30 to 60 min, telephone or video conference); (2) Unstructured observations; (3) Structured observations using DCM. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006 approach). |

| Noone & Jenkins, 2018 [40] Scotland | To (1) deliver a community-based gardening program for PLWD; (2) explore participants’ experiences of the gardening sessions; (3) explore the experience of the gardening program from the perspectives of those who care for PLWD, using qualitative semi-structured interviews. Community-based gardening program in a garden was located on the grounds of a community hall in Glasgow, which hosted a day center for PLWD. Weekly gardening sessions over six weeks. Specific study design not stated. | 6 PLWD 3 professionals who had experience of working with PLWD in the garden—one OT, two community gardeners. 4 care staff from day center: n = 2 care workers, n = 1 care manager; n =1 care assistant | Pragmatist methodological perspective drawing upon elements of phenomenology and action research Data collection methods were guided by phenomenological principles: (1) Informal semi-structured interviews following each session; (2) researcher’s observations documented after each session; (3) individual semi-structured interviews with carers and professionals Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006 framework). |

| Oher, Tingberg, & Bengtsson, 2024 [25] Sweden | To (1) explore the needs of individuals with YOD in a garden setting; (2) generate design-related knowledge for ‘dementia-friendly’ outdoor environments. An 8 week long nature-based program in Alnarp’s rehabilitation garden on the campus of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Southern Sweden), a specifically developed garden based on research from landscape architecture, environmental psychology, and medical science. Qualitative. | 6 people with YOD: 2 women, 4 men Age—years: mean = 61.5; range = 51–67 Type of dementia: AD, n = 5; VD, n = 1 Severity of dementia: mild cognitive decline, n = 3; mild–moderate cognitive decline, n = 1; moderate cognitive decline, n = 2 5 staff members—2 Memory Clinic staff, both nurses; 3 members of the Rehabilitation Garden team: an OT, a horticultural engineer, and a PT and ergonomist. | Semi-structured interviews. Content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs 2008). |

| Robertson et al., 2020 [41] Scotland | To investigate the experiences of people with and without dementia who attend a national ‘dementia-friendly’ walking group initiative. “Paths for All”, a Scottish charity that supports National Health Service trusts, local authorities, and community organizations to run a range of free walking activities for local people. ‘Dementia-friendly’ walks, a subset of a wider group of free-at-the-point-of-delivery ‘health walks’ which aim to promote activity amongst people who live with long-term health conditions. Co-produced, participatory methodology drawing on an existing community research partnership. | Participant characteristics not reported. | (1) walking interviews conducted concurrently with two participants from each group, one person identified as having dementia alongside a carer, friend or relative (2) focus group following each walk—walkers, volunteers, and walk leaders were invited to discuss the key facilitators, barriers, and benefits of participating in each of the walking groups. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke 2006) |

| Schols, van der Schriek, & van Meel, 2006 [42] Netherlands | To (1) get a first impression of the effects of day care at a small dairy farm; (2) discern the most striking differences between patients in institutional day care and patients attending day care on the farm. Care Farm “Enjoying Life” (Den Hout), an existing dairy farm, with capacity to provide day care for elderly patients with physical disabilities and/or dementia who still live at home. Nursing home day care in Nursing Home de Riethorst (Geertruidenberg). Cross-sectional study. | 13 Care Farm PLWD participants: Men:Women-2:1 Age, mean—years = 74 Farming background, n = 13 Dementia type: AD 77%; VD 8%; Other 15% Reported problematic behavior before start of day care: n = 10 (76%) Sundowning before start of day care: n = 10 (76%) 24 Day care at nursing home PLWD participants: Men:Women-1:1 Age, mean—years = 74 Farming background, n = 5 Dementia type: AD 71%; VD 13%; Other 16% Reported problematic behavior before start of day care: n = 22 (92%) Sundowning before start of day care: n = 21 (88%) | (1) activities of daily living (ADL, Barthel score); (2) reported “problematic behavior”; (3) # and types of medication; (4) active or inactive involvement in day care activities during the day; (5) therapeutic intervention; (6) family satisfaction |

| Smith-Carrier et al., 2021 [43] Canada | To explore (1) experiences of therapeutic gardening for PLWD; (2) perspectives on senses and emotions elicited in the gardening process that promote well-being. Therapeutic gardening program offered at an adult day center in Southwestern Ontario, conducted in a large outdoor garden outside the center building. The program is delivered over multiple waves and participants are involved in all aspects of the gardening cycle from spring clean-up, planting, garden maintenance, harvest, to clean-up in the fall. IPA | 6 PLWD, early stages All of Caucasian descent. | (1) Observations with field notes. (2) Six waves of semi-structured interviews over the various planning, planting, tending, pruning, and harvesting seasons of the garden. Analysis: case-by-case using a systematic, qualitative analysis; transformed into narrative accounts reflecting the researchers’ analytic interpretation. |

| Author(s) Year | Results |

|---|---|

| de Bruin et al., 2009 [26] | GCF activities included the following: (1) domestic activities [chopping vegetables, cooking, dish washing, and laying and clearing the table]; (2) farm- and animal-related activities and garden- or yard-related activities. More activities were organized outdoors at GCFs. GCFs: average = 2.0 activities daily, e.g., going for a walk, watching and feeding animals, painting fences, gardening; RDCs: average = 0.8 activities daily, e.g., going for a walk, shopping at the market. GCFs: the majority of activities were performed by individuals or one or more subgroups. RDCs: more activities were performed with almost the entire group. * Men (72.3% of observations) and * women (77.6% of observations) at GFCs participated more in organized activities compared to men (59.2%) and women (53.8%) at RDCs. Men and women at RDCs sat and pottered significantly (p < 0.001) more than men and women at GCFs. Men and women at GCFs spent significantly more time outdoors than counterparts at RDCs (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001). Men and women at RDCs were significantly more frequently involved in activities performed while sitting and requiring no movements or only minor hand and arm movements than men and women at GCFs (p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Activities that required sitting with arm movements were rarely observed at GCFs. Men at RDCs spent significantly more time lying down while resting than men at GCFs (p < 0.001). Activities requiring standing with/without arm movements were more often performed by the women at GCFs than those at the RDCs (p = 0.002). Standing activities involving whole-body movements were most frequently performed by men at GCFs who did these activities significantly more often than men at RDCs (p < 0.001). Women at RDCs hardly ever performed walking activities that required whole-body movements. These types of activities were done significantly more often by women at GCFs (p < 0.001). * study participant characteristics reported as male/female, but men/women used in the results section. |

| de Bruin et al., 2012 [27] | GCF: mean # of days of care per week (SD): Cohort A: 1.8 (0.7); Cohort B: 2.5 (1.3); Cohort C: 2.7 (1.1) RDC, mean # of days of care per week (SD): Cohort A: 2.1 (0.9); Cohort B: 1.9 (0.7); Cohort C: 2.4 (1.0) In all but one participant, BADL performance did not change significantly over time. Average rates of change in BADL did not differ significantly between groups within the three cohorts. In all but three participants, IDDLD Initiative nitiative scores did not change significantly over time. IDDLD Required Assistance scores did not change significantly. The average rates of change in IADL performance did not differ significantly between groups within the three cohorts. In all but one participant, # of diseases and medications did not change significantly over time. # of psychotropic medications did not change significantly. Average rates of changes in # of diseases and medications did not differ significantly between groups within the three cohorts. |

| de Bruin et al., 2015 [28] | Main Themes and sub-themes: (1) Reasons for initiating services for PLWD: (1.1) the most important reason was enabling social interactions; (1.2) stimulation of activities; (1.3) enabling participation in useful and meaningful activities. (2) Reasons for initiating services for caregivers: (2.1) reducing caregiver burden; (2.2) enabling own activities and social interactions; (2.3) increasing freedom (3) Factors related to selecting GCF services setting: A farm setting was a deliberate choice: (3.1) PLWD liked to be outdoors, be physically active, were fond of animals/gardening; (3.2) the presence of animals, the spacious and outdoor environment, and atmosphere; (3.3) disliked the RDC facilities, institutional environment, activities offered, expectation they would not connect with other participants. (4) Value of GCF related to social participation: (4.1) activities were socially relevant; (4.2) enabled social participation in other domains, specifically “paid employment” and “volunteer work”; (4.3) gave PLWD something to do, made them feel useful and meaningful, made them feel “part of something”, e.g., made them feel able to contribute to something; (4.4) increased social interactions and gave PLWD a sense of belonging. |

| de Bruin et al., 2021 [29] | Main Themes and sub-themes: (1) Motivation to initiate nature-based ADSs in an urban area: (1.1) possibility of being active; (1.2) possibility of spending time outdoors; (1.3) presence of green and natural environment; (1.4) opportunity to meet people of one’s own age; (1.5) presence of a diverse range of stimuli; (1.6) relaxing atmosphere, staff were friendly; (1.7) short travel distance between one’s home and the ADS location; (1.8) availability of a place at the ADS location. (2) Value of nature-based ADS for PLWD: (2.1) contact with nature and animals; (2.2) activity engagement; (2.3) different types of activities and jobs, and outdoor environment with different places to go to; (2.4) ADS provided structure; a fixed day structure, dedicated times for activities and jobs; seasons play a role in offering a certain structure; (2.5) social interactions were facilitated with other participants, staff, volunteers, other visitors; some considered social interaction the most valued aspect; interactions enabled PLWD to remain part of society and stimulated a sense of belonging; (2.6) communal dining stimulates social interactions between participants and healthy eating; (2.7) important and satisfying to do meaningful work, particularly for younger participants; (2.8) focus on normal daily life, a normal, non-institutional kind of place; no stigmatizing; sense of belonging; everyone is equal; can participate in society for as long as possible. (3) Value of nature-based ADS for family carers: (3.1) respite—could unwind … did not have to take care of or worry about their relative for the day; (3.2) maintaining carers’ own activities and social contacts; (3.3) reassurance—relative was at the right place, which he or she liked to visit, therefore, did not feel guilty about shifting responsibilities to an ADS for some days a week; (3.4) practical and emotional support received from ADS professionals, which made family carers feel less alone in caring for their relative. |

| Ellingsen-Dalskau et al., 2021 [30] | No statistical differences between FDC and RDC groups for most commonly observed activities: (1) sitting (23.2% in total) (p = 0.55, SE 5.58); (2) joint meals (21.9% in total) (p = 0.98, SE 4.16). The three most common activities on FDCs following sitting and common meals were the following: (1) farming and working with animals (17.3%; only occurred at the farms); (2) walking outdoors (15.3%); (3) domestic and cooking activities (8.9%). Walking outdoors occurred significantly more often at FDC compared to RDC (p = 0.007, SE 4.15). No significant difference was found for domestic and cooking activities (p = 0.10, SE 4.64) between groups. The three most common activities in RDC following sitting and common meals were the following: (1) quiz, music, and spiritual activities (17.2%); (2) exercise and dancing (11.8%); (3) listening to staff reading (10.9%). FDC participants: (1) had higher levels of physical effort—39.4% observations of participants standing up or walking around at FDC versus 13.2% at RDC, p < 0.001, SE 4.36; (2) were outdoors more—42.3% observations of attendees being outdoors at FDC versus 2.6% at RDC, p < 0.001, SE 7.79; (3) experienced more social interaction—81.5% observations of social interaction taking place at FDC versus 64.3% at RDC, p = 0.006, SE 5.55; (4) had more positive mood—94.2% observations of positive or very positive mood at FDC versus 79.6% at RDC, p = 0.004, SE 4.4. |

| Finnanger Garshol et al., 2020 [31] | FDC participants spent 22.81 minutes more in moderate activity each day, equating to 159.67 minutes more for the entire week than RDC participants. On the days at the farm, FDC participants spent 25.85 minutes less in sedentary activity (p = 0.012), 40.37 minutes more in light activity (p < 0.001), 12.53 minutes more in moderate activity (p = 0.032), and took 1043.36 more steps (p = 0.005). |

| Finnanger-Garshol et al., 2022 [32] | Statistically significant difference in mood scores between groups for the activities sitting, eating/drinking and reading, with the FDC group having higher scores. Significantly higher mean mood scores in the FDC group compared to the RDC group for sedentary physical effort, no social interaction, interaction with another person, interaction with two or more people, being inside and being engaged in activity. Attending FDCs was statistically significantly associated with higher emotional well-being than attending RDCs. Increased physical effort, being outdoors, and farm-based activities were not associated with emotional well-being. |

| Hall et al., 2018 [33] | DCM: (1) 60.42% of the time participants were either extremely engaged or in a state of extremely high well-being; (2) 17.00% of the time people were either very engaged or in a state of high well-being; (3) 5.53% of the time participants were in a state of visible ill-being. Four themes were identified as follows: (1) Combining structured and unstructured activity—Unstructured activity afforded autonomy to assume risks as participants saw fit; structured activities provided a degree of direction to enhance experiences; (2) The importance of teamwork—Participants took care of others’ gardens when they did not attend, participants worked together to achieve common goals; (3) Garden reminiscence—Participants talked about their pasts with others, fostering a deep and meaningful rapport between the participants who frequently engaged with each other in an unstructured manner; (4) Positive risk taking—Risks and barriers noted were consideration related to falls, light sunburn, potential dehydration, the consumption of non-ripened food from the sensory pot, feeling too warm even when sitting in shade, and fatigue through overstimulation. Caregiver questionnaire findings: (1) participants frequently and spontaneously talked about their garden experiences on the day they participated and on days other than when they were in the garden; (2) emotional expression when talking about their gardening—‘happy’ and ‘enthusiastic’ most frequently reported emotions; (3) participants viewed their work in the garden as a personal accomplishment, being recognized by staff and others as good at gardening; (4) at times being ‘upset’ was expressed when an undesirable or unexpected event occurred; (5) attitude about gardening experience influenced emotional status for a period beyond the immediate discussion, oftentimes for hours after the discussion, sometimes for the entire day. |

| Hassink et al., 2019 [34] | Five main types of initiatives identified were as follows: (1) Social entrepreneurs offering nature-based ADS using their own facilities or with existing facilities; (2) Nursing homes opening their gardens to PLWD living at home; (3) Social care organizations setting up nature-based activities; (4) Community gardens set up by citizens; (5) Hybrid initiatives—care organizations initiating nature-based ADS with institutional partners or social entrepreneurs. There were differences in locations; nature-based activities; # and diversity of participants. The importance of quality of care was identified, but initiators had different ideas about this. Approaches included the following: (1) the medical approach, focusing on safety; (2) the community approach, focusing on participation in the community. Initiators from nursing homes and care organizations: (1) agreed on the importance of focusing on well-being rather than only medical care; (2) stressed the importance of quality control and providing quality care as their core business, which involved minimizing risks and employing professional personnel with a formal education, a systematic monitoring of the satisfaction of the care, and an acknowledgement that multidisciplinary consultation was needed. Issues included attention to poisonous plants, water hazards, and the risk of stumbling. Social entrepreneurs, social care, and the neighborhood initiative: (1) had little affinity with formal quality control issues and protocols; (2) emphasized the importance of freedom for clients and providing a setting that is as normal as possible. All initiators stressed: (1) entrepreneurial behavior as key in realizing an ADS in an urban area; (2) the importance of having knowledge about financing, dementia care, and running a project. Challenges: (1) scarcity of green spaces, especially in city centers; (2) persuading PLWD to participate in activities/go outside in bad weather; (3) funding was decreasing while support needed by PLWD was increasing. Some work was not funded and many activities were only possible with volunteers; (4) developing support and ownership among employees. Risks included the following: a loss of enthusiasm and commitment when processes were complicated, the realization that the ADS took more time than expected, employees getting a job elsewhere; (5) the high workload of care employees because they saw the nature-based activities as additional to their normal tasks. Specific ADS-type challenges: (1) social entrepreneurs—finding a suitable location/establishing a new location requires considerable investments in time, financial resources, e.g., for building, equipment, and perseverance; (2) nursing homes—involving PLWD living at home to establish interaction with the neighborhood, commitment among employees and support within the organization, continuation when the funding ends or the project leader moves to another position, costs for maintenance of the garden and making sure there is sufficient expertise to manage the garden and involve PLWD in nature-based activities; (3) social care organization—the difficulty in finding volunteers who are interested and able to take responsibility for PLWD visiting the city farm, location needs to be close to the day center of the welfare organization to allow people to get there, arranging transportation; (4) citizens’ initiative—getting support from the municipality, getting competent volunteers involved who were willing to invest time in the initiative and who were also able to build a good relationship with PLWD, securing the back-up and support from an organization with expertise in dementia care; (5) hybrid initiatives—engaging committed managers of different organizations, combining different sources of funding, taking differences in interests and work culture between organizations into account. |

| Hewitt et al., 2013 [24] | There was an increase in mean BWBP scores for the first eight sessions, followed by a leveling off of the scores due to reaching a ceiling. There was no significant difference in BWBP scores (original Profile-t(5) = 1.43, p = 0.21; amended version-t(5) = 0.88, p = 0.425) between the first and last sessions. There was no statistical change in MMSE at 6 months; there was a statistically significant decline in MMSE at 12 months (paired t(5) = 3.88, p = 0.012). Themes: (1) At 6 months—what difference has the gardening group made? (1.1) Self-identity; (1.2) Companionship; (1.3) Orientation. (2) ‘What difference has the gardening group meant for you, personally?’ (2.1) Respite/independence for participant; (2.2) Safe physical activity and knowing a loved one was being looked after. (3) End of project—What difference did the gardening group make: (3.1) Enjoyment; (3.2) Independence; (3.3) Feeling useful, having achievement; (3.4) Feeling valued; (3.5) Reduced anxiety— ‘Small size of group led to reduced anxiety for participant and carer’. |

| Ibsen et al., 2018 [35] | The highest # of farms were in the central and south-eastern part of Norway.

n = 227 total participants:

Personnel: Regular nurse, n = 17 (53.1%); health-educated personnel, n = 25 (78.1%); volunteer workers n = 20 (62.5%) All highlighted the opportunity to choose activities individually tailored for each participant.

|

| Ibsen et al., 2020 [36] | Fifteen farms (60.0%) had health-educated personnel with a bachelor’s degree. All farms, but one, had animals. The mean # (SD) of days at FDC per week = 2.2 (0.9); the average # (SD) of participants per day = 5.9 (1.3); the average # (SD) of employees per day = 2.2 (0.6); the average # of participants per employee = 2.7 The average time (SD) spent at the FDC = 5.8 h/day (1.3). The mean time (SD) spent outdoors summer and winter = 2.2 h (0.6); Summer—average 2.9 h (range 1 to 4.5 h) outdoors; Winter—average 1.4 h (range 0.5 to 3 h) outdoors. The mean # (SD) physical active (≥20 min) days per week mean = 2.9 (3.6). QoL associated with the following: the experience of having social support (p = 0.023); a low score on depressive symptoms (p< 0.001); spending time outdoors at the farm (p < 0.001). In total, 14% of all the variance in QoL was explained by the variable time spent outdoors at the FDC. |

| Ibsen T.L, & Eriksen S., 2021 [37] | # of days at FDC per week: range = 1 to 4 days; 1 day (n = 1), 2 days (n = 5), 3 days (n = 3), 4 days (n = 1). Three main categories (and corresponding sub-categories): (1) Social relations—being part of a fellowship. (1.1) Social relationships that occurred = to other participants, providers and animals. (1.2) A special fellowship due to the similar situation of having dementia helped participants use humor as a coping strategy with their diagnosis. (2) Being occupied at the farm—occupied in different ways with activities that provided meaning and a feeling of usefulness. (2.1) Feels like working—the farm was viewed as a place of work, the activity was meaningful and experienced as ‘real work’. (2.2) Being active—there was a great variety of activities, physically active while working; there were many walking opportunities. (2.3) Being outdoors—added to their experience; natural surroundings; the outdoors facilitated natural conversations; attached to animals, animals were perceived as more like a part of the outdoor scenery. (3) Individually tailored service—(3.1) being seen for who I am—providers facilitated work tasks in accordance with their individual abilities. This revealed a feeling of being seen by the provider as someone who had skills that were useful and even needed; personality was respected and taken seriously; (3.2) being one who contributes—participants had influence on the activities and they, to some extent, could choose between different tasks; there was the opportunity for participants to do things that might be new and challenging; this contributed to the participants’ feeling of mastery and self-esteem since they were able to handle the delegated work; (3.3) attending day care at a farm makes me feel like a real participant—an active part in the relationships with others and in the work and help; the farm context was a natural setting for outdoor activities, and work tasks were characterized as authentic farm work that needed to be done; participants were allowed to use their competency at different tasks and had the opportunity to have an influence on their stay at the day care. |

| Innes et al., 2024 [38] | Themes: (1) Outdoor-based care was conceptualized as the following: (1) built environment—the nature and design of the built environment influenced whether participants described a location as favorable for outdoor-based activities for PLWD; and (2) outdoor activities—a range of formal activities promoting engagement with the outdoors, in particular, natural environments. PLWD, older adults, and care partners also talked about less formalized activities as important either on their own or together in locations they enjoyed. (2) Perceived benefits: (2.1) mental—emotional well-being, the outdoors is a place where mood and emotions could be experienced in a positive manner, the mood improves, a sense of freedom is experienced, feelings of acceptance and connections to people and their communities are realized. Gardening activities were perceived as an opportunity for therapeutic benefit and to give a sense of purpose for PLWD; (2.2) social well-being—connecting with others, chance social connections, being outdoors allows for placing oneself to be with others and choosing to engage or not, there is the opportunity to be part of, and build, a community, see wildlife, and be with pets and animals; (2.3) physical well-being—moving one’s body, physiological benefits. |

| Morris et al., 2021 [39] | Before the GLC interview, four themes: (1) Well-being through gardening—(1.1) a general love of gardening and enjoyment of being outdoors; (1.2) access to an outdoor space and the opportunity to engage in gardening was important; (1.3) relaxation and the therapeutic benefit of gardening was important; (1.4) participants enjoyed watching plants grow, giving them a sense of satisfaction and a feeling of purpose. (2) Social connectedness—(2.1) gardening provided a social environment where they could connect with other people; the importance of sustaining and building upon these relationships through the GLC.; (2.2) friendships with like-minded people in similar situations, which are based on a mutual purpose, enabled individuals to work together bringing enjoyment and satisfaction. Friendships were a key motivator for current and former care partners attending the GLC; (2.3) gardening provided opportunity to connect socially and engage in new activities; (2.4) former care partners highlighted that through a communal gardening group, they could share their experiences and empathize with other group members; (2.5) GLC offers a trusted social environment where members feel supported and can fulfil a need to support others. (3) Increasing knowledge—(3.1) a motivation for participation was to improve the knowledge of gardening and dementia; (3.2) learning among participants—varying levels of expertise create an environment where group members can learn from each other and further enhance a sense of social connection. (4) Active participation—(4.1) a desire to engage in a range of activities related to participants’ creative interests and activities they would like to spend more time doing. DCM findings during GLC: participants spent the majority of their time engaged and experiencing good overall levels of well-being. At no point during mapping was ill-being recorded. The mean ME score was +2.5 indicating a good and sustained overall level of mood and engagement. Post-GLC, follow-up interviews, five themes: (1) What is a good life?—Having active participation in a social life is a key aspect of living a good life. (2) Active participation—participants reflected positively on the autonomy afforded by the GLC—the number of different things on offer and the lack of prescribed ways of conducting oneself during sessions. (3) Social connectedness and peer support—peer support was experienced and a supportive environment was created. (4) What could be improved?—More PLWD attending groups like the GLC. (5) Impact of COVID-19 |

| Noone & Jenkins, 2018 [40] | Three themes: (1) Gardening and identity—gardening activities offered the opportunity to express elements of identity that had become less prominent on their dementia journeys. (1.1) Care staff believed the ability to participate in an activity that the participant enjoyed had improved their level of engagement. (1.2) Express aspects of the participant’s character; (1.3) there was the opportunity for the participant to share his/her extensive gardening knowledge. (2) Gardening and agency—a sense of agency was expressed through gardening. (2.1) There was a sense of control and involvement in the project; (2.2) a freedom of choice afforded through the project represented an opportunity that was lacking in their everyday lives; (2.3) the opportunity to work autonomously in the garden appeared to be particularly enjoyable; (2.4) the ability to work autonomously and make free choices was a primary benefit of gardening for PLWD; (2.5) the group’s successes had defied the expectations of others; (2.6) the ability of the garden to offer PLWD a sense of freedom from the restrictions impinging upon their everyday lives. (3) Gardening and community—gardening created an opportunity to create a new social dynamic. (3.1) This saw the emergence of a new social group, changing dynamics as a consequence of the study; (3.2) this gave participants the confidence to break out of their social routine; (3.3) the creation of a new group dynamic, distinct from the larger day center group, and mutual interest in it encouraged the development of new friendships. |

| Oher, Tingberg, & Bengtsson, 2024 [25] | Two main categories (and related sub-categories): (A) Being Comfortable in the outdoor environment—represented the need to be able to, and dare to, use the outdoor environment. Seven environmental qualities which constitute considerations of the physical environment were discussed by people with YOD and/or staff: (A1) closeness and easy; (A2) entrance and enclosure; (A3) safety and security; (A4) familiarity; (A5) orientation and way finding; (A6) different options in different kinds of weather; (A7) calmness. (B) Access to nature and surrounding life—represented what makes spending time in the outdoors interesting, enjoyable, rewarding, and meaningful. Thirteen environmental qualities, which constitute considerations of the physical environment, for designers to pursue in order to increase the possibility of both stimulation and restoration: (B1) contact with surrounding life; (B2) social opportunities; (B3) joyful and meaningful activities; (B4) sensory experiences of nature; (B5) species richness and variety; (B6) seasons changing in nature; (B7) culture and connection to the past; (B8) openness; (B9) symbolism and reflection; (B10) space; (B11) serenity and peace; (B12) wild nature; (B13) secluded and protected. |

| Robertson et al., 2020 [41] | Themes identified: (1) Being with Others: Social Inclusion, Participation and Confidence—(1.1) the most prominent benefit was the increase in social integration and social health more broadly. (1.2) Individuals interacted with a more diverse group than might happen elsewhere; (1.3) attending the walks gave PLWD the opportunity to meet and spend time with other people, in a relatively safe, supported environment; (1.4) the combination of a predominantly open membership combined with group norms encouraged informal engagement and PLWD were recognized and valued as ‘full’ members. (1.5) Being part of a group often offered an opportunity to connect organically with others who had shared/similar experiences and created understanding between members which fostered enabling (rather than disabling) practices; this created a sense of community, and friendships emerged. (2) Reciprocity and Looking Out for Each Other: Creating a Safe and Secure Social Environment—(2.1) groups created a safe and secure social environment where participants engaged in meaningful activities supportive of their physical, mental, and social health. (2.2) Safety and security were important to walkers with and without dementia, and walk leaders were considered within the ethos of dementia-inclusiveness. (2.3) Participants valued the walking groups as a place where family carers and the person they cared for could spend some time apart, gaining some respite from each other; (2.4) opportunities for mixed abilities, e.g., different length walks depending on mobility and support from other group members, this meant that carers could feel reassured that their partner would be looked after by others while they spent time with other people; (2.5) potential catalyst for PLWD to develop new social relationships and networks, while supporting them to be active participants in their local communities. (3) Accessing the Outdoors: Promoting Agency and Capacity through Physical Activities—(3.1) walking groups functioned as part of a wider initiative to support attendees to take proactive steps to maintain health; (3.2) Walking was discussed as proactive and reactive responses to health concerns, and as a valuable and valid method of promoting/maintaining health; (3.3) walking was an activity that could be made accessible for people at various stages of their dementia journey; (3.4) walking groups functioned as spaces where the challenges faced by PLWD were validated and respected alongside challenges faced by others rather than in isolation; (3.5) physical gains—walking could reassert confidence, agency, and capacity; (3.6) walking was socially situated; exercise was more enjoyable when performed with others; (3.7) a continued participation via walking was enabled as a healthy and meaningful activity which reinforced a broader commitment to and acceptance of adaptation and enablement for all members irrespective of a formal diagnosis. |

| Schols, van der Schriek, & van Meel, 2006 [42] | Care Farm participants:

Day care at nursing home participants:

|

| Smith-Carrier et al., 2021 [43] | Master Themes: (1) Digging in the dirt: Activating the sense of touch—(1.1) participants clearly enjoyed being in the natural environment and derived much pleasure from activating their senses through gardening. (1.2) ‘All of it’ (the experience of gardening) was valuable; (1.3) the sense of touch, particularly the feel of the dirt, emerged as the most important; something everyone can do. (2) Reminiscence ignited: Links to the past in our eternal gardens—(2.1) all senses were activated in the garden, bringing about precious memories. The sense of smell was especially identified as a key mechanism for cultivating reminiscence; (2.2) participating in the garden had the power to bring forward pleasant memories and erase painful thoughts of the present. (3) A sense of accomplishment for engaging in productive work—(3.1) gardening gave an implicit sense of being productive, and of contributing to the greater good, prestige of hard work, satisfaction. (3.2) Gardening was not perceived to be a favourite pastime or hobby but a job, with the prestige and status that comes with hard work. (4) Being together: The social benefits of gardening—(4.1) shared sense of being part of something larger than oneself. (4.2) Working with the group reduces sensations of physical pain. (4.3) Gardening fosters the development of intimate relationships and provides camaraderie that gives a feeling of connection. (5) Finding meaning: Curiosity, wonder, and lifelong learning—(5.1) participants used the seasons as an analogy for the circle/cycle of life. (5.2) Regardless of one’s age or stage in the cycle of life, individuals maintain a deep sense of curiosity and the need to keep learning. Lifelong learning, curiosity and wonder. (6) ‘It’s just another season’: Cultivating peace and hope—(6.1) gardening was meaningful as it gave a sense of hope for the future. (6.2) In the garden participants were able to ‘focus on the present’; this mindful awareness brought them peace, and hope. (7) Reaping the benefits of positive and physical well-being—(7.1) both the physical and therapeutic exercises of gardening had positive effects on mental health, reducing feelings of depression and increasing levels of happiness. (7.2) Positive emotions generated in the garden are not only experienced during the actual gardening activity but stay with participants for extended periods afterward. |

3.2. Types of Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs

3.3. Opportunities and Benefits

3.3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.4. Challenges

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLWD | People living with dementia |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Revies and Meta-Analyses |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| YOD | Young onset dementia |

| AD | Alsheimer’s disease |

| ADS | Adult day services |

| GCF | Green care farm |

| FDC | Farm-based day care |

| GLC | Good Life Club |

| COREQ | Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

Appendix A

| Query | |

|---|---|

| 1 | (alzheimer disease.mp OR “alzheimer-type dementia (atd)”.mp OR “alzheimer type dementia (atd)”.mp OR “dementia, alzheimer-type (atd)”.mp OR alzheimer dementia.mp OR dementia, alzheimer.mp OR alzheimer’s disease.mp) OR ((Alzheimer Disease/OR Alzheimer Disease.mp) OR (Dementia, Vascular/OR Dementia, Vascular.mp) OR (Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration/OR Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration.mp) OR (Lewy Body Disease/OR Lewy Body Disease.mp) OR (Mixed Dementias/OR Mixed Dementias.mp)) |

| 2 | Caregivers/OR Caregivers.mp OR (caregivers.mp OR caregiver.mp OR care givers.mp OR care giver.mp OR carers.mp OR carer.mp OR family caregiver, family.mp OR caregivers, family.mp OR family caregiver.mp OR spouse caregiver, spouse.mp OR caregivers, spouse.mp OR spouse caregiver.mp OR informal caregiver, informal.mp OR caregivers, informal.mp OR informal caregiver.mp) |

| 3 | Independent Living/OR (independent living.mp OR living, independent.mp) |

| 4 | (Nature/OR nature.mp) OR (Gardens.mp OR Horticulture.mp) OR (gardens.mp OR garden.mp) |

| 5 | Support Group.mp OR Support Groups.mp OR Community Support.mp OR Group, Support.mp OR Groups, Support.mp OR Program Development/OR (program development.mp OR development, program.mp OR program descriptions.mp OR description, program.mp OR descriptions, program.mp OR program description.mp) |

| 6 | limit to (english language and humans and yr = “2000–2024”) |

References

- World Health Organization. Dementia. 15 March 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Cloutier Fisher, D. Making Meaningful Connections a Profile of Social Isolation Among Older Adults in Small Town and Small City, British Columbia: Final Report; University of Victoria Centre on Aging: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey, L.; Chandaria, K.; Quince, C.; Kane, M.; Saunders, T. Dementia 2012: A National Challenge. 2012. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/alzheimers_society_dementia_2012-_full_report.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Swaffer, K. Dementia: Stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia 2014, 13, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, S.R.; Szymczynska, P. Meaningful activities for improving the wellbeing of people with dementia: Beyond mere pleasure to meeting fundamental psychological needs. Perspect. Public Health 2016, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharani, A.; Zaidi, S.N.Z.; Jury, F.; Vatter, S.; Hill, D.; Leroi, I. The long-term impact of loneliness and social isolation on depression and anxiety in memory clinic attendees and their care partners: A longitudinal actor–partner interdependence model. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2022, 8, e12235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.J. The Landmark Study Report 1: Navigating the Path Forward for Dementia in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/documents/Landmark-Study-Report-1-Path_Alzheimer-Society-Canada_0.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Demirbas, M.; Hahn-Pedersen, J.H.; Jørgensen, H.L. Comparison Between Burden of Care Partners of Individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease Versus Individuals with Other Chronic Diseases. Neurol. Ther. 2023, 12, 1051–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer Society of Canada. Heads Up for Healthier Living: For People with Alzheimer’s Disease and Their Families. 2011. Available online: https://alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/documents/Heads-Up-for-Healthier-Living-Alzheimer-Society.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Penninkilampi, R.; Casey, A.-N.; Singh, M.F.; Brodaty, H. The Association between Social Engagement, Loneliness, and Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 66, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Jung, J.H.; Kang, H.W.; Jung, I.C. Non-pharmacological interventions for patients with dementia: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e17279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg-Weger, M.; Stewart, D.B. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Persons with Dementia. Mo. Med. 2017, 114, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDermott, O.; Charlesworth, G.; Hogervorst, E.; Stoner, C.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Spector, A.; Cispke, E.; Orrell, M. Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: A synthesis of systematic reviews. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 23, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.K.; Tischler, V.; Wong, G.H.Y.; Lau, W.Y.T.; Spector, A. Systematic review of the current psychosocial interventions for people with moderate to severe dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1313–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, C.; Fernandes, S.; Romão, A.; Fernandes, J.B. Current trends in psychotherapies and psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: A scoping review of randomized controlled trials. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1286475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaur, S.; Cherukuri, S.H.S.; Murshed, S.M.; Purev-Ochir, A.; Abdelmassih, E.; Hanna, F. The Impact of Regular Physical Activity on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Dementia Patients in High-Income Countries—A Systematic Scoping Review. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuohy, D.; Kingston, L.; Carey, E.; Graham, M.; Dore, L.; Doody, O. A scoping review on the psychosocial interventions used in day care service for people living with dementia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Owen, S.; Opdebeeck, C.; Ledingham, K.; Connell, J.; Quinn, C.; Page, S.; Clare, L.; Lu, N.; Nan, L. Provision of Outdoor Nature-Based Activity for Older People with Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review from the ENLIVEN Project. Health Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.L.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, P.; Watts, C.; Hussey, J.; Power, K.; Williams, T. Does a Structured Gardening Programme Improve Well-Being in Young-Onset Dementia? A Preliminary Study. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 76, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oher, N.; Tingberg, J.; Bengtsson, A. The Design of Health Promoting Outdoor Environments for People with Young-Onset Dementia—A Study from a Rehabilitation Garden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, S.R.; Oosting, S.J.; Kuin, Y.; Hoefnagels, E.C.M.; Blauw, Y.H.; de Groot, L.C.P.G.M.; Schols, J.M.G.A. Green Care Farms Promote Activity Among Elderly People with Dementia. J. Hous. Elder. 2009, 23, 368–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, S.; Oosting, S.; Tobi, H.; Enders-Slegers, M.-J.; van der Zijpp, A.; Schols, J. Comparing day care at green care farms and at regular day care facilities with regard to their effects on functional performance of community-dwelling older people with dementia. Dementia 2012, 11, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, S.R.; Stoop, A.; Molema, C.C.M.; Vaandrager, L.; Hop, P.J.W.M.; Baan, C.A. Green Care Farms: An Innovative Type of Adult Day Service to Stimulate Social Participation of People with Dementia. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, S.R.; Buist, Y.; Hassink, J.; Vaandrager, L. ‘I want to make myself useful’: The value of nature-based adult day services in urban areas for people with dementia and their family carers. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen-Dalskau, L.H.; de Boer, B.; Pedersen, I. Comparing the care environment at farm-based and regular day care for people with dementia in Norway-An observational study. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnanger Garshol, B.; Ellingsen-Dalskau, L.H.; Pedersen, I. Physical activity in people with dementia attending farm-based dementia day care—A comparative actigraphy study. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnanger-Garshol, B.; Pedersen, I.; Patil, G.; Eriksen, S.; Ellingsen-Dalskau, L.H. Emotional well-being in people with dementia—A comparative study of farm-based and regular day care services in Norway. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e1734–e1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Mitchell, G.; Webber, C.; Johnson, K. Effect of horticultural therapy on wellbeing among dementia day care programme participants: A mixed-methods study (Innovative Practice). Dementia 2018, 17, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, J.; Vaandrager, L.; Buist, Y.; de Bruin, S. Characteristics and challenges for the development of nature-based adult day services in urban areas for people with dementia and their family caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, T.L.; Eriksen, S.; Patil, G.G. Farm-based day care in Norway—A complementary service for people with dementia. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, T.L.; Kirkevold, Ø.; Patil, G.G.; Eriksen, S. People with dementia attending farm-based day care in Norway—Individual and farm characteristics associated with participants’ quality of life. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 28, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibsen, T.L.; Eriksen, S. The experience of attending a farm-based day care service from the perspective of people with dementia: A qualitative study. Dementia 2021, 20, 1356–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, A.; Dal Bello-Haas, V.; Burke, E.; Lu, D.; McLeod, M.; Dupuis, C. Understandings and Perceived Benefits of Outdoor-Based Support for People Living with Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.; Innes, A.; Smith, S.; Wilson, J.; Bushell, S.; Wyatt, M. A qualitative evaluation of the impact of a Good Life Club on people living with dementia and care partners. Dementia 2021, 20, 2478–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, S.; Jenkins, N. Digging for Dementia: Exploring the experience of community gardening from the perspectives of people with dementia. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.M.; Gibson, G.; Pemble, C.; Harrison, R.; Strachan, K.; Thorburn, S. “It Is Part of Belonging”: Walking Groups to Promote Social Health amongst People Living with Dementia. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schols, J.M.; van der Schriek-van Meel, C. Day care for demented elderly in a dairy farm setting: Positive first impressions. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2006, 7, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Carrier, T.A.; Beres, L.; Johnson, K.; Blake, C.; Howard, J. Digging into the experiences of therapeutic gardening for people with dementia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Dementia 2021, 20, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, S.; Blackman, T.; Martyr, A.; Van Schaik, P. The impact of early dementia on outdoor life: A ‘shrinking world’? Dementia 2008, 7, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buru, T.; Kállay, É.; Cantor, M.; Papuc, I. The Investigation of the Relationship Between Exposure to Nature and Emotional Well-Being. A Theoretical Review. In Environmental and Human Impact of Buildings; Moga, L., Șoimoșan, T.M., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M.P.; DeVille, N.V.; Elliott, E.G.; Schiff, J.E.; Wilt, G.E.; Hart, J.E.; James, P. Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Oyekanmi, K.O.; Gibson, A.; South, E.C.; Bocarro, J.; Hipp, J.A. Nature Prescriptions for Health: A Review of Evidence and Research Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickerdike, L.; Booth, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Farley, K.; Wright, K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Buffoli, M.; Rebecchi, A.; Croci, R.; Oradini-Alacreu, A.; Stirparo, G.; Marino, A.; Odone, A.; Capolongo, S.; Signorelli, C. Association between Urban Greenspace and Health: A Systematic Review of Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howarth, M.; Brettle, A.; Hardman, M.; Maden, M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: A scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Barton, J. Nature-Based Interventions and Mind-Body Interventions: Saving Public Health Costs Whilst Increasing Life Satisfaction and Happiness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bao, W.W.; Yang, B.Y.; Liang, J.H.; Gui, Z.H.; Huang, S.; Chen, Y.C.; Dong, G.H.; Chen, Y.J. Association between greenspace and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 817, 152513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, L. Outdoor green space exposure and brain health measures related to Alzheimer’s disease: A rapid review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler Davis, S.; Benkowitz, C.; Nield, L.; Dayson, C. Green spaces and the impact on cognitive frailty: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1278542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, H.K.; Peoples, H. Experiences related to quality of life in people with dementia living in institutional settings—A meta-aggregation. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 83, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, L.; MacAndrew, M.; Doherty, K.; Fielding, E.; Beattie, E. Characteristics and value of ‘meaningful activity’ for people living with dementia in residential aged care facilities: “You’re still part of the world, not just existing”. Dementia 2023, 22, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Albert, M.; Fox, N.; Goedert, M.; Kivipelto, M.; Mestre-Ferrandiz, J.; Middleton, L.T. Why has therapy development for dementia failed in the last two decades? Alzheimer’s Dement. 2016, 12, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde-van Buuringen, M.; Hendriks-van der Sar, R.; Verbeek, H.; Achterberg, W.P.; Caljouw, M.A.A. The effect of garden use on quality of life and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in people living with dementia in nursing homes: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1044271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensma, R.; van den Bogerd, N.; Dijkstra, K.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.; Krabbendam, L.; de Vries, R.; Maas, J. How to implement nature-based interventions in hospitals, long-term care facilities for elderly, and rehabilitation centers: A scoping review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 103, 128587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzon, A.; Rebba, V.; Paccagnella, O.; Rigon, M.; Boniolo, G. The value of supportive care: A systematic review of cost-effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for dementia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population Related | |

| Alzheimer’s disease Lewy body dementia Frontal temporal dementia Vascular dementia Multiple etiology (mixed) dementia, e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia Degenerative neurologic health condition related to dementia, e.g., Parkinson’s disease Disease severity: mild, moderate, severe Young onset dementia Adult population Living status of PLWD: community-dwelling | Cognitive impairment due to other health condition, e.g., traumatic brain injury Mild cognitive impairment |

| Under 18 years of age (children, pediatric population) | |

| Living status of PLWD: long-term care; congregate care facility; hospital; hospice | |

| Activity and Intervention Related | |

| Outdoors—built or natural environment Nature, parks, gardens, horticulture Outdoor activities Outdoor-based care, nature-based care | Animal-based activities, animal-assisted therapy Indoor activities Indoor leisure/recreation/sports/exercise |

| Concept(s) and Outcome(s) Explored/Examined/Evaluated | |

| Type of outdoor-based care Benefit(s)—psychological, social, physical, mental, emotional, health- and wellness-related Opportunity/Opportunities—e.g., prospects, facilitators, favorable circumstances at any level, e.g., individual, care partner, organization, community, policy Challenge(s)—e.g., barriers, risk(s) at any level, e.g., individual, care partner, organization, community, policy | Other concept(s) or outcome(s) |

| Document Type and Study Related | |

| Full text available, peer-reviewed Any study design, e.g., quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, multi-methods Ability to delineate and extract data related to purpose, e.g., if mixed populations (community-dwelling versus long-term care) or (mixed interventions outdoor-based versus indoor-based) Published in the English language | Unable to obtain full text Non-peer-reviewed papers Grey literature, e.g., dissertations, editorials, book chapters, book reviews, letters to editor, position papers, conceptual discussions and commentaries, news articles, reports Unable to delineate/separate data in order to extract data related to purpose Published in languages other than English |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Innes, A.; McLeod, M.; Burke, E.; Lu, D.; Dupuis, C.; Dal Bello-Haas, V. Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Scoping Review. J. Dement. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2030021

Innes A, McLeod M, Burke E, Lu D, Dupuis C, Dal Bello-Haas V. Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Scoping Review. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease. 2025; 2(3):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2030021

Chicago/Turabian StyleInnes, Anthea, Mason McLeod, Equity Burke, Dylan Lu, Constance Dupuis, and Vanina Dal Bello-Haas. 2025. "Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Scoping Review" Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease 2, no. 3: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2030021

APA StyleInnes, A., McLeod, M., Burke, E., Lu, D., Dupuis, C., & Dal Bello-Haas, V. (2025). Outdoor-Based Care and Support Programs for Community-Dwelling People Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners: A Scoping Review. Journal of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease, 2(3), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/jdad2030021