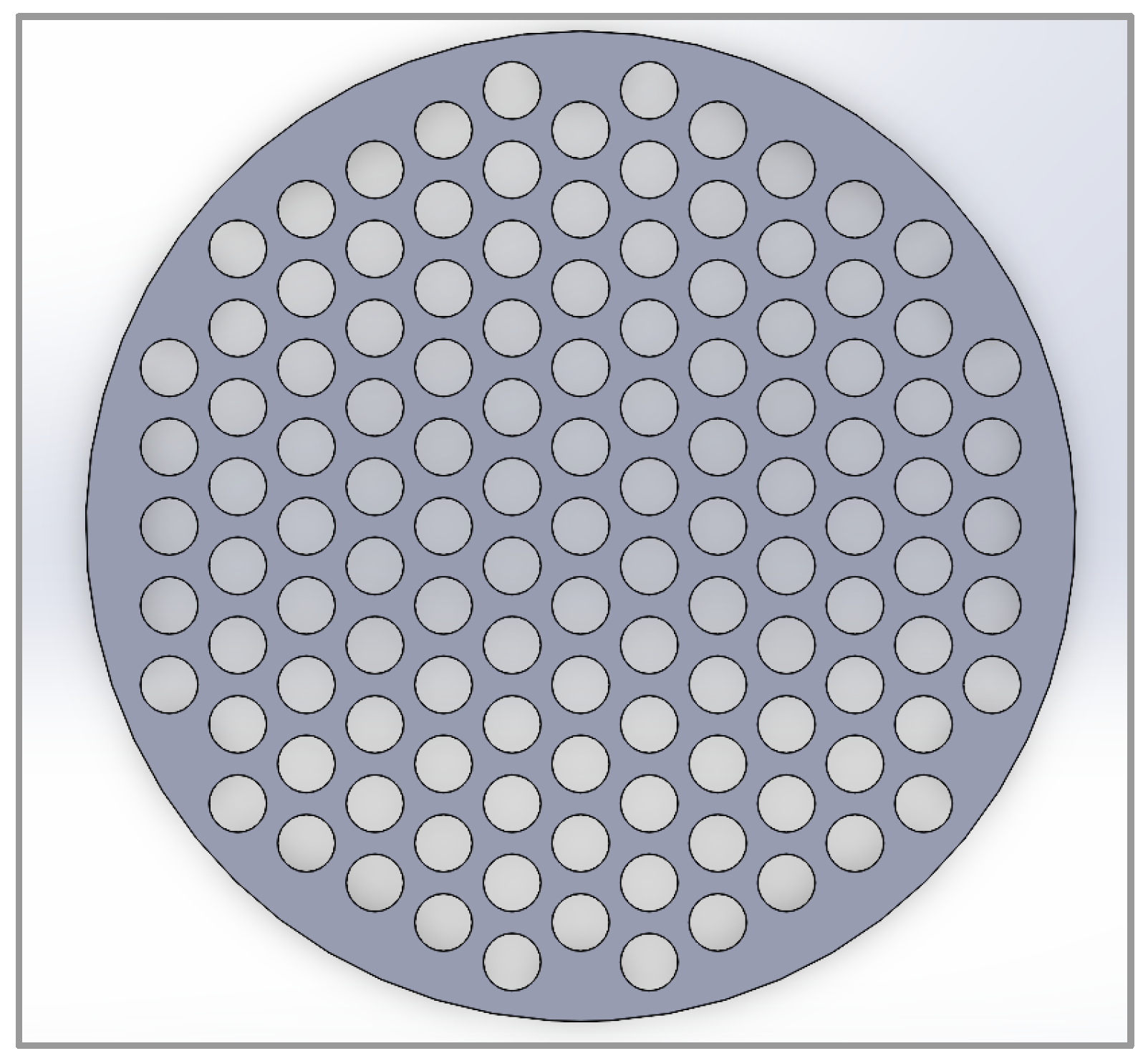

3.1. Geometry and Modeling Approach

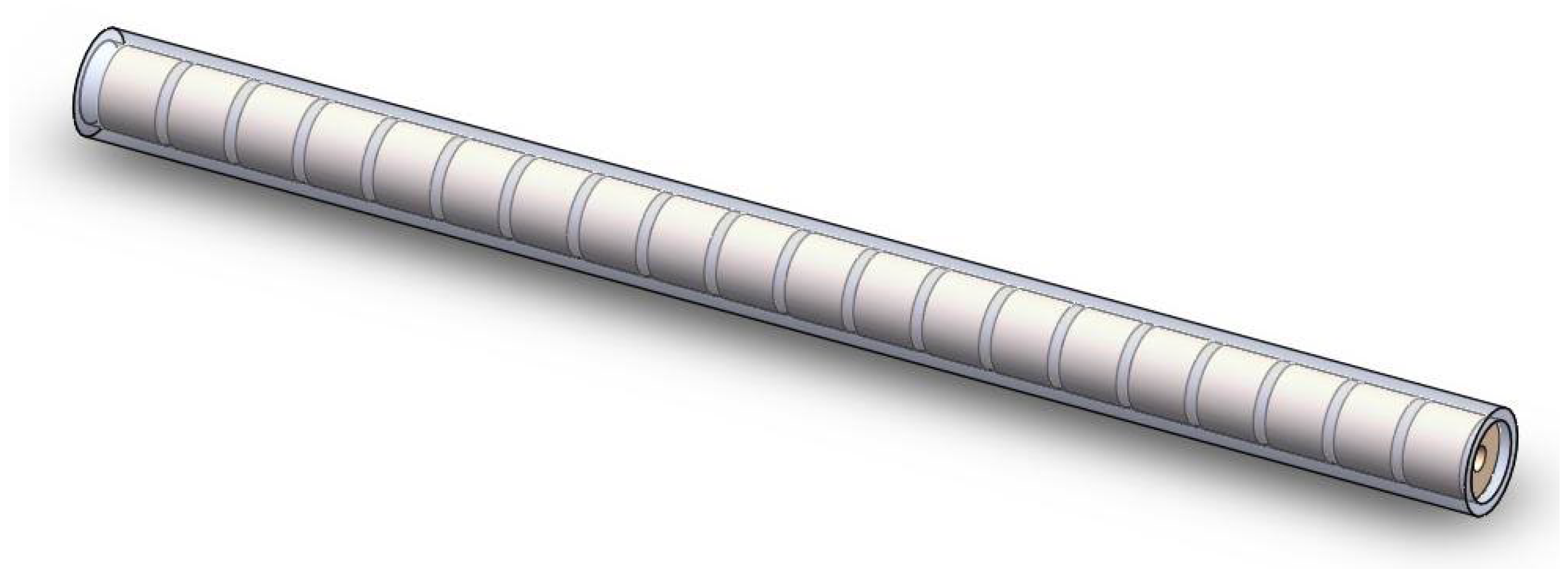

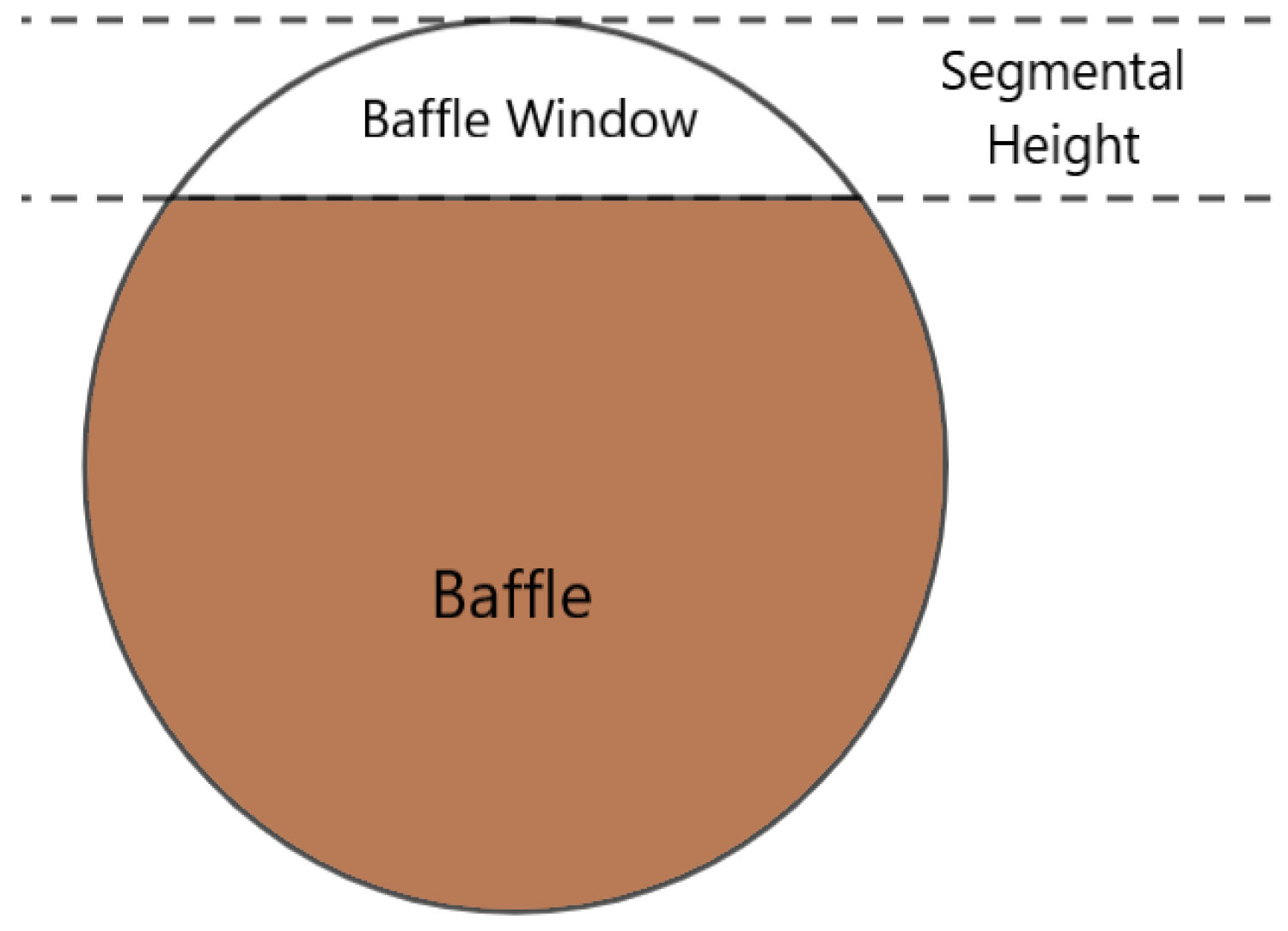

When creating the reactor geometry in COMSOL, one-quarter of the total reactor was utilized. Since each quarter is identical, simulating one section should yield results equivalent to modeling the complete reactor, while significantly reducing computational time [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The model was designed to allow easy modifications of variables for testing multiple reactors. In this article, the variables that will be varied are the inner tube diameter and the tube spacing. The geometry for each reactor was initially sketched in SolidWorks 2023 and then imported into COMSOL. This made testing different reactors efficient as the software provided capability to design tube bundles with a triangular pitch (

) and different diameters

(D) that could be varied as required.

To ensure numerical accuracy, a grid independence study was conducted by systematically refining the computational mesh using COMSOL’s predefined element size sequences. Different mesh levels were examined, and the transient solution was evaluated at t = 3000 s using the hotspot temperature difference (ΔT = Thotspot − Tinitial) as a representative metric. The adopted mesh yielded ΔT = 40.33 K, while the immediately coarser mesh produced ΔT = 40.23 K, corresponding to a relative difference of approximately 0.25%. Further mesh refinement resulted in negligible changes relative to the additional computational cost. Based on this convergence behavior, the selected mesh was deemed grid-independent and was used for all subsequent simulations.

Model verification in this study is conducted through literature-based validation and physical consistency checks, as direct experimental validation at the present reactor scale (1 m diameter) is currently unavailable in the open literature and beyond the scope of this work. The numerical framework is based on conservation equations and LaNi

5 hydrogen absorption kinetics that have been experimentally characterized and validated in prior small-scale studies, and subsequently adopted in numerous numerical and reactor-scale investigations for comparative and scale-up analyses [

2,

4,

13,

14]. In addition, the model reproduces physically consistent trends, including hotspot formation under insufficient heat removal and sensitivity of absorption time to cooling tube distribution, supporting its suitability for comparative reactor design evaluation.

3.3. Volumetric Occupancy of LaNi5 in Reactor Core

For the first simulation, the tube diameter remained the same, but the triangular pitch and number of tubes varied, allowing the comparison of reaction times for reactors containing varying amounts of

powder. The heat transfer coefficient was kept consistent for each trial (3768

). For this case, the Reynolds number was determined using ṁ = 5.36 kg/s,

D = 0.06 m, and

μ = 0.00139 Pa·s. The resulting Reynolds number (

) was 81,829. With a Prandtl number of

= 9.52 and a seawater thermal conductivity of

= 0.587

, the Nusselt number and heat transfer coefficient obtained were 385.2 and 3768

, respectively. Each reactor had the same diameter, cooling tube diameter, and mass flow rate. The reactor specifications are listed in

Table 2. The initial reactor configurations tested are listed in

Table 3, the operating and kinetic parameters governing the hydrogen absorption process in LaNi

5 are summarized in

Table 4a, and the thermophysical properties of H

2 and LaNi

5 powder are listed in

Table 4b. Low hydrogen supply pressure in these simulations led to poor cooling times; therefore, the supply pressure was set to 30 bar, similar to that used in other larger-scale metal hydride reactors [

28]. The aluminum tube thickness must be at least 4 mm [

29] to withstand a pressure of 60 bar, twice the operating pressure.

For all reactor configurations, the cooling fluid velocity should be in the range 0.5–2 m/s [

30]. The initial reactor configurations had a cooling fluid mass flow rate of 5.36 kg/s, or 1.85 m/s, which fell within the desired range. The reactor length in this instance was limited.

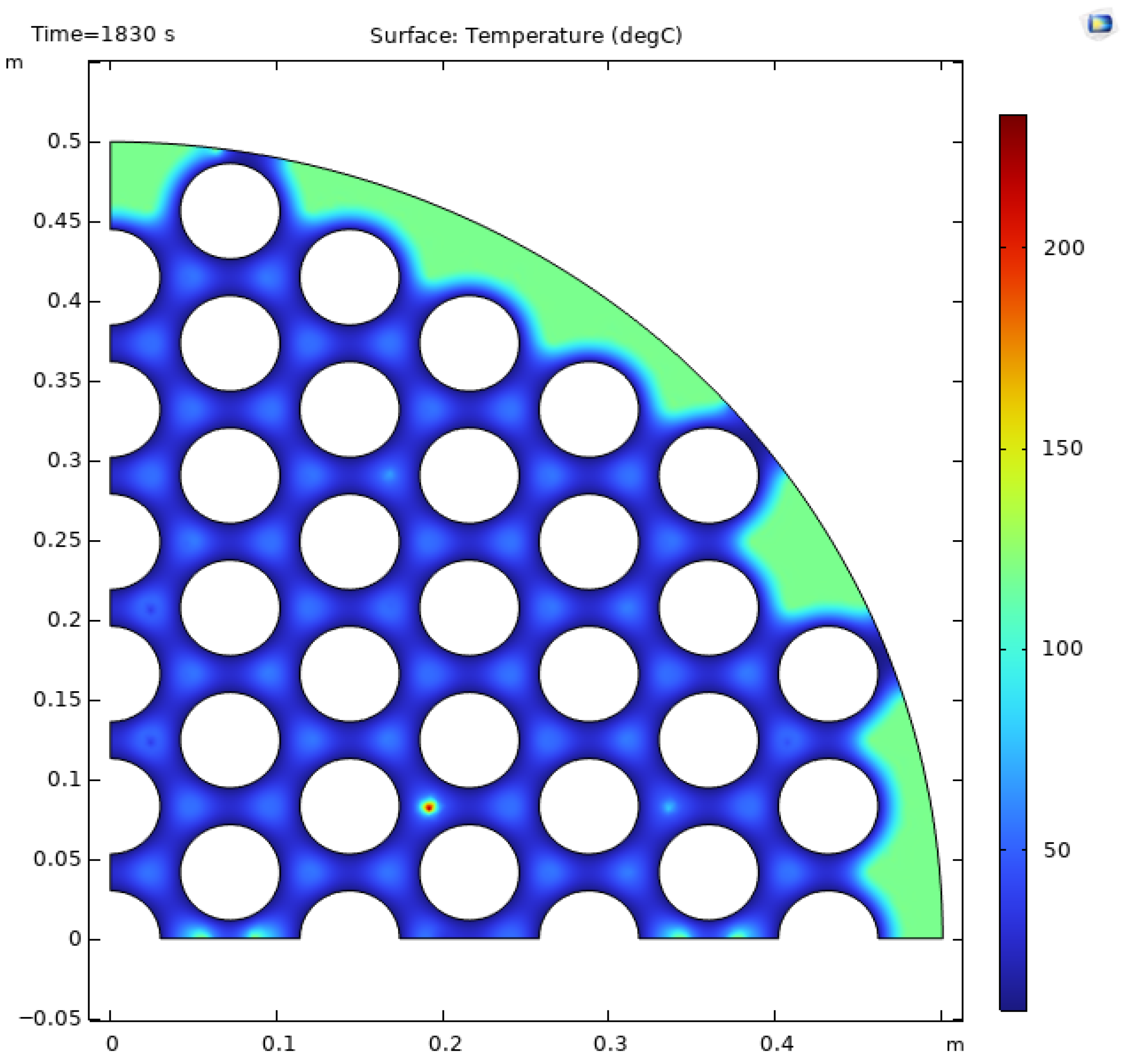

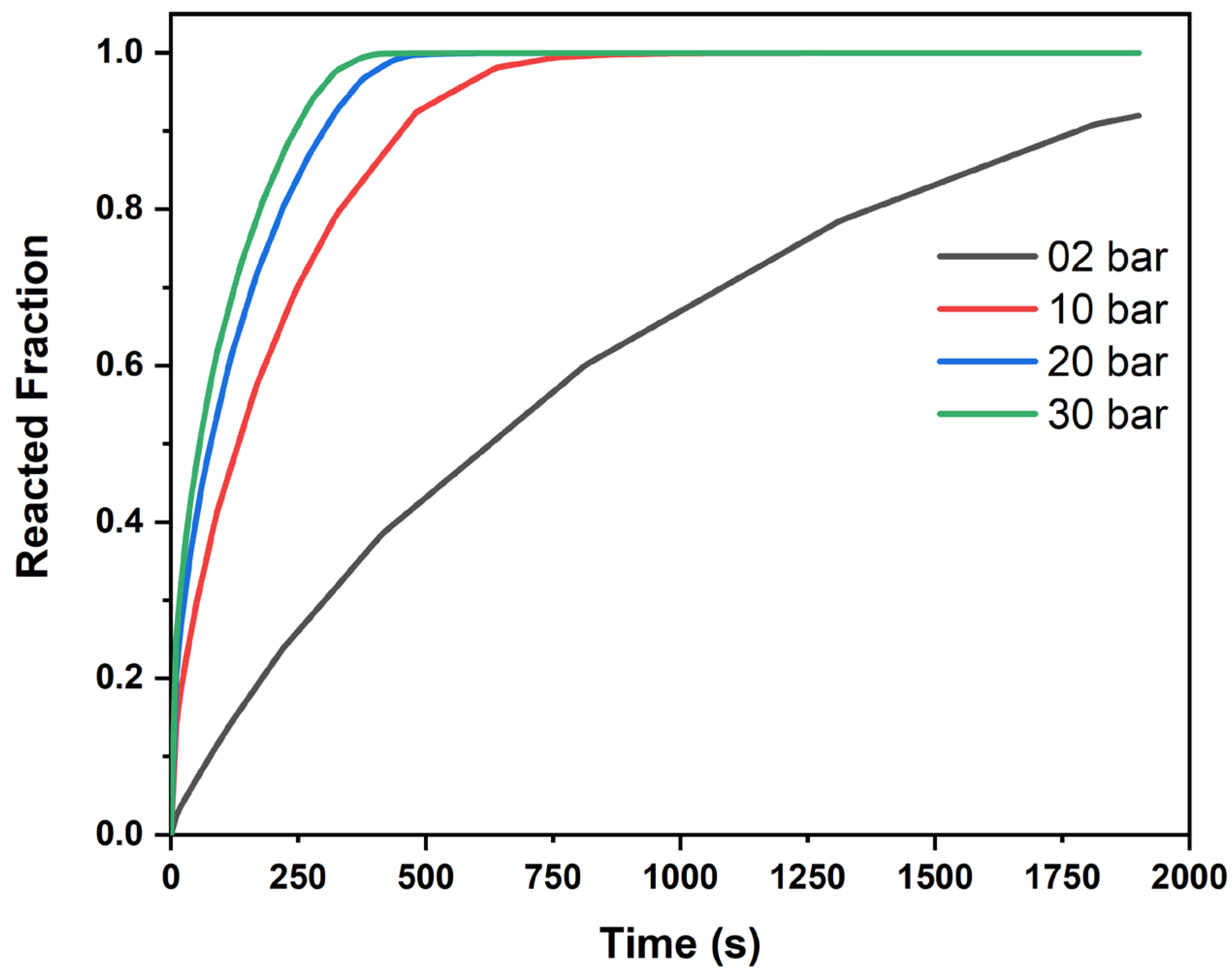

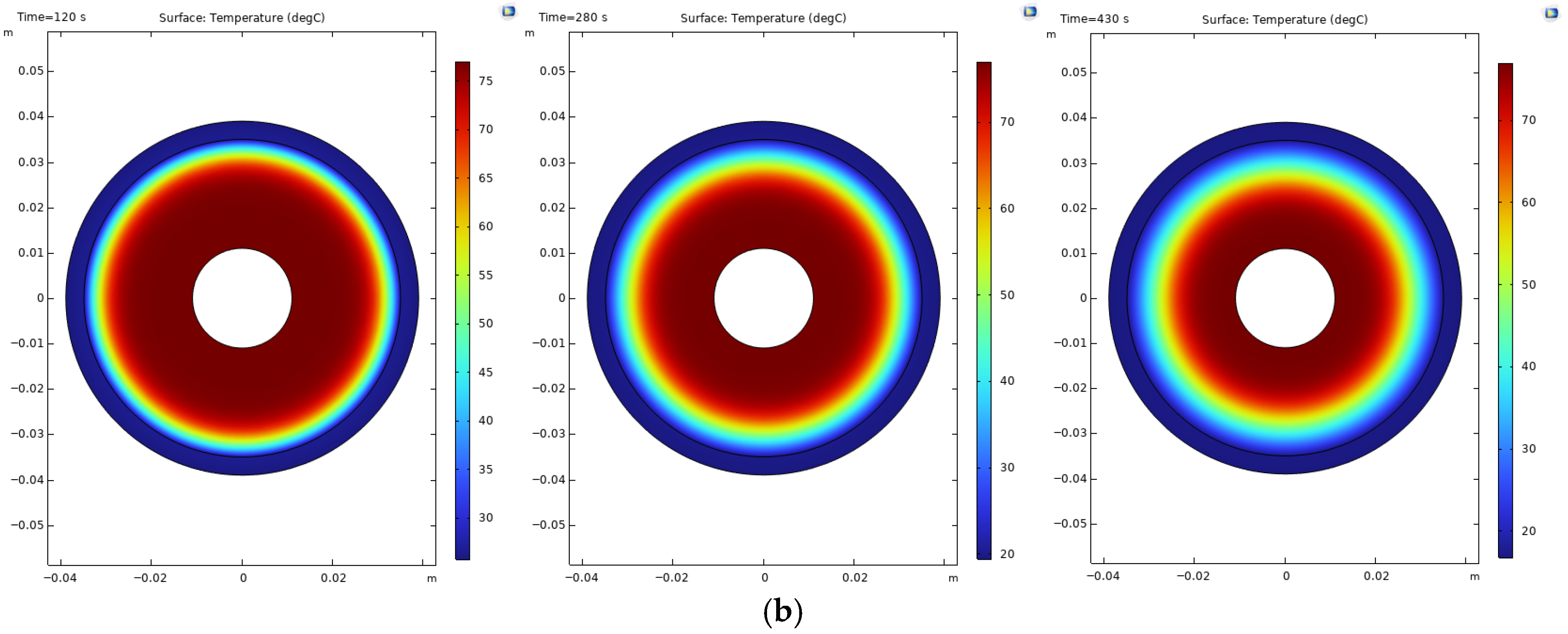

The hydrogen charging time is defined as the time it takes for the supplied hydrogen to be absorbed by 90% of the metal hydride material. This is also referred to as the “90% cooling time”. The results in

Figure 1 highlight the importance of tube spacing relative to other factors. For example, reactor 2 (

n = 85) resulted in a 90% cooling time of 3720 s, whereas reactor 3 (

n = 97) could not reach a 90% reacted fraction within the 5000 s heat transfer simulation. Although reactor 3 incorporated a larger volume for cooling, it exhibited a poorer cooling performance due to the formation of hotspots around its outer region.

This same trend is observed between reactors 5 and 6 (

n = 121 and

n = 139, respectively). Reactor 5 reached a 90% cooling time of 1830 s, where reactor 6 required 3330 s to reach the same level of hydrogen absorption. These findings showed that the tube spacing and count are important, but it is equally important to ensure equal distribution of the cooling tubes around the outside of the reactor. Reactor 5 (

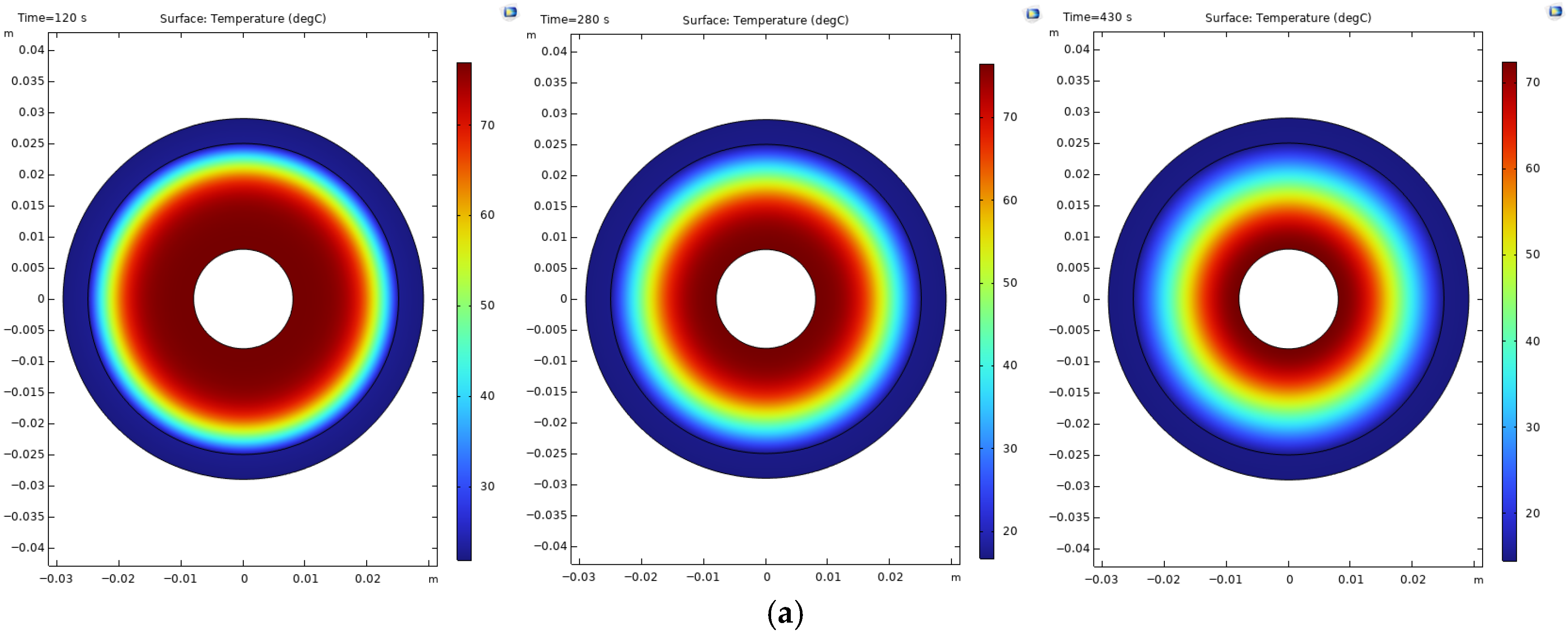

Figure 2) illustrates minimal hotspot formation around the outside of the reactor compared to the reactors with a poor cooling time, such as reactors 3 and 6.

The presence of hotspots on the hydride bed is an indication of uneven temperature distribution. These zones of localized high temperature can hamper the hydrogen absorption kinetics, produce thermal stress concentrations, and, with prolonged cycling, deteriorate materials and reduce the mechanical integrity of the reactor shell. Hence, optimized tube spacing and balanced cooling distribution are essential measures to ameliorate hotspot temperatures and to achieve thermal uniformity, structural reliability, and safe operation of large-scale metal hydride reactors.

Overall, four of the six reactor configurations, reactors 2, 4, 5, and 6, achieved 90% cooling within the 5000 s simulation window. Reactor 2 displayed a 90% cooling time of 3720 s, highlighting a favorable balance between storage capacity and heat removal. From these simulations, maintaining a metal hydride storage volume of approximately 55–60% appears reasonable. However, the arrangement of and the number of cooling tubes require further optimization to minimize temperature non-uniformity and enhance overall reactor performance.

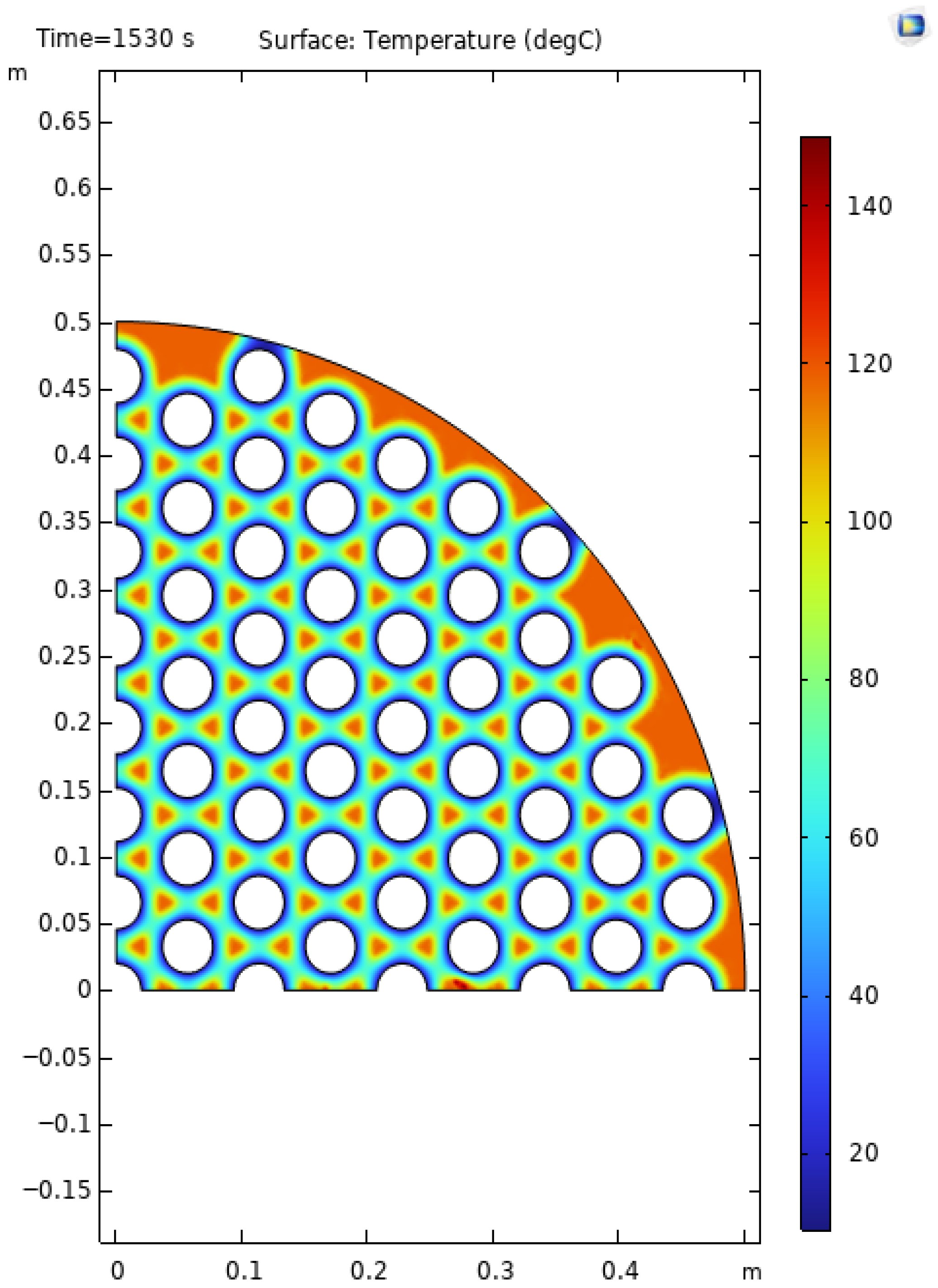

Figure 1 shows the reacted fraction for each tube configuration. Increasing the number of tubes initially results in a faster rate of reaction as expected, but as previously mentioned, the tube spacing and diameter must be optimized for 90% of the reaction to be completed. When the metal hydride bed is not evenly cooled, the reaction rate significantly decreases after reaching 80%. This effect is evident in

Figure 3 with the 139-tube reactor (reactor 6). A large portion of the metal hydride absorbs hydrogen within 1000 s (approximately 82%), yet the remaining 8% requires 2000 s due to insufficient cooling. The hot spots in this reactor are shown in

Figure 3.

3.4. Optimization via Variable Tube Diameter and Spacing

After these initial simulations, other reactors were tested with metal hydride storage volume between 55–60%, by varying the outer tube diameter (

) and triangular pitch (

) for each test. The reactor geometries in

Table 5 were simulated in this test:

The flow velocity from the first set of simulations was maintained for these simulations (~1.85 m/s). Due to the changing diameter of the cooling tubes, the mass flow rate for each reactor differed, impacting the heat transfer coefficient of the cooling fluid.

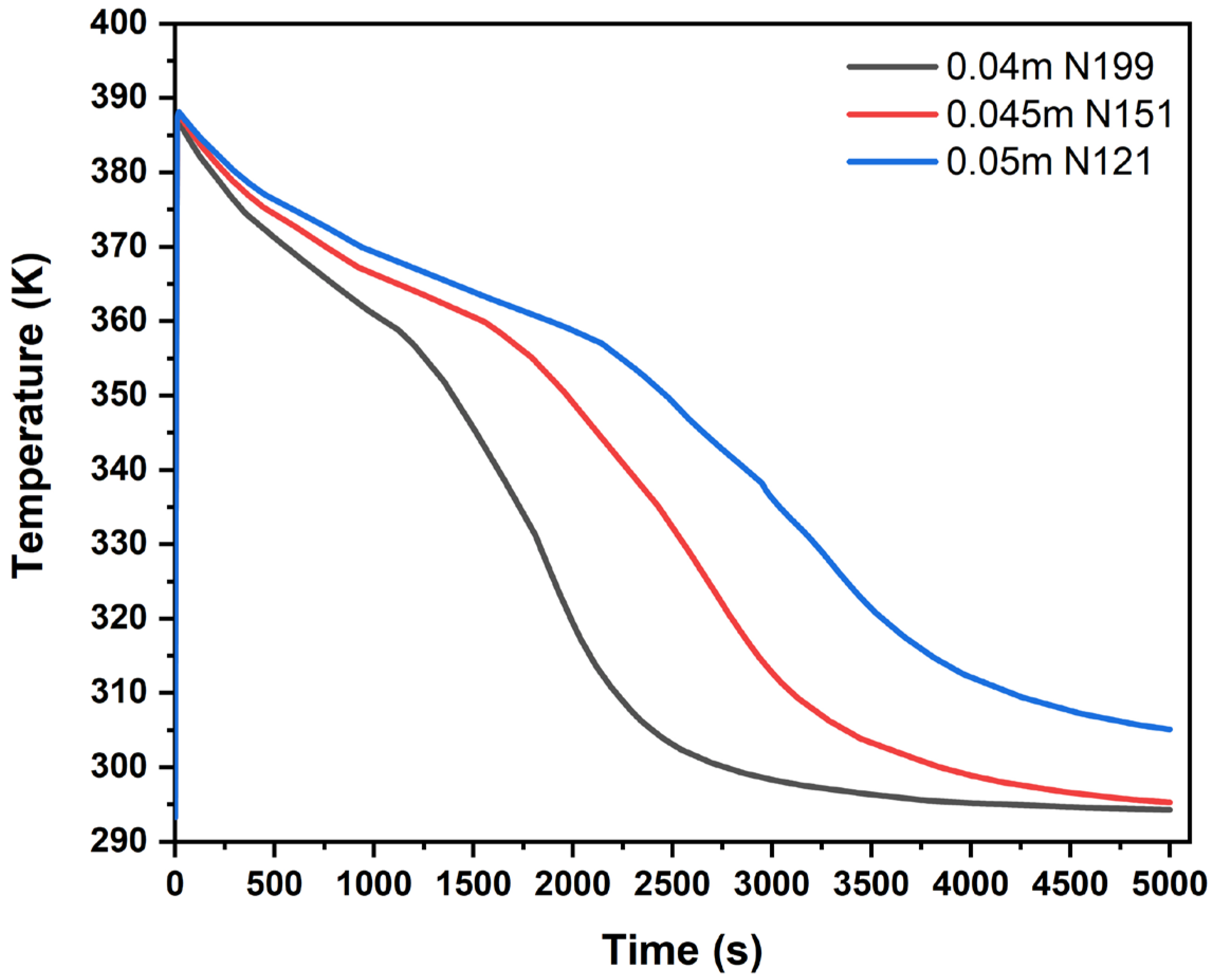

The simulations of reactors 7–9 (

Figure 4) showed that when the tube spacing adequately cools the outer portion of the reactor, the number of cooling tubes becomes the main factor to reach 90% reaction completion. Reactors 7, 8, and 9 achieved 90% reaction completion in 1540 s, 2110 s, and 2730 s, respectively. Reactor 9, like reactor 5, had the same number of cooling tubes but a smaller tube diameter and a slightly increased spacing between tubes. This tube spacing was increased from 8.3 cm to 8.4 cm. The primary purpose of this reactor test was to determine if reactor 5, which had the best cooling time from the previous experiment, was effectively utilizing the area for cooling fluid. Reactor 9 did show a slower cooling time by roughly 15 min but had a metal hydride storage percent volume of nearly 60% compared to 44% in reactor 5. Reactors 7 and 8 were modelled to maintain the volume occupied by the metal hydride and to assess how much the cooling time could be extended by adding more cooling tubes. Reactor 7 had a significant decrease in cooling time but also utilized 199 cooling tubes compared to reactors 5 and 9.

Figure 5 shows the temperature distribution for reactors 7 and 8. All the reactors tested still contained hotspots around the reactor exterior, regardless of the tube bundle configuration. The tube spacing is determined to ensure that over 90% of the metal hydride powder is in contact with the cooling fluid. This allows the tube diameter and number of tubes to be adjusted to achieve the desired 90% cooling time. If cooling time is a critical reactor design factor, a higher tube count is typically selected, despite the increased reactor complexity. Conversely, if cooling times between 1800 and 3600 s are deemed acceptable, the tube count can be reduced to simplify the reactor design. In this scenario, tube spacing must be carefully optimized to minimize hotspots within the reactor. Future design considerations may include implementing one or more of the following:

- 1.

External cooling jacket: This might effectively eliminate the hotspots around the outer portion of the reactor.

- 2.

Circular tube bundle: This would help ensure that the cooling effects reach 90–100% of the metal hydride powder.

- 3.

Changing reactor shell geometry: A polygonal shape might better utilize storage space by better fitting the shape of the tube bundle.