1. Introduction

Molten salt heat exchangers are crucial components in systems requiring high-temperature heat transfer and energy storage, especially in renewable energy and advanced nuclear technologies [

1,

2,

3]. Their ability to operate efficiently at high temperatures while offering significant energy storage capacity makes them highly valuable in modern energy systems. They have high thermal stability. They can remain stable at high temperatures, typically between 250 °C and 1000 °C [

4], depending on the salt composition. They have high heat capacity. They can store a significant amount of heat, making them ideal for thermal energy storage (TES) systems. They have low vapor pressure. Molten salts have low vapor pressure, reducing the risk of pressurization in the system and making it safer, and they have a wide range of operating temperatures. This makes them ideal for processes like solar power generation or high-temperature industrial heating.

HITEC molten salt is a specialized heat transfer and thermal energy storage medium primarily used in industrial processes and solar thermal power plants. HITEC is a eutectic blend of sodium nitrate, sodium nitrite, and potassium nitrate. It melts at a relatively low temperature compared to its individual components. It has favorable thermal characteristics [

5].

1.1. Literature Review of Thermal Hydraulics of Molten Salt Heat Exchangers

Numerical modeling can be employed to simulate the behavior of molten salt heat exchangers. Wu et al. have studied the laminar natural convection heat transfer characteristics of molten salt around a horizontal cylinder [

6]. The natural convective heat transfer coefficient of molten salt around a horizontal cylinder has been studied by using commercial FLUENT CFD software under different

Ra number ranges. They have shown that the natural convection heat transfer of multi-component molten salts can be predicted by Fand’s empirical correlation when the

Ra number is within the range of 1.57 × 10

−2 to 2.03 × 10

6. Zeng et al. have carried out CFD simulation in order to study the thermal stress distribution characteristics of the heat exchanger of a molten salt steam generation system under different working conditions and different layouts [

7]. A paper written by Cao et al. [

8] discusses conventional combined gas turbine system coupling with a molten salt thermal energy storage device, as well as the system operation’s flexibility, peak regulation ability, and economy. An F-class combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) system has been investigated in this study which fundamentally consists of two gas turbines, one steam turbine, and two waste heat boilers. EBSILON Professional thermodynamic software version 16 has been used in order to develop the model of the CCGT system in this study, which can calculate the performance behavior and efficiency of the CCGT system under the wide range of operating conditions. The results show that after coupling with the molten salt energy storage, the electrical output regulation capability of the system increases by 30–44.7%, which improves the response speed of power demand [

8]. Chen et al. have performed a numerical simulation study on the mixed convective heat transfer of molten salt in a horizontal square tube with single-side heating. A good agreement has been reached between numerical results and correlations [

9]. Raj et al. studied the effects of a molten salt-air heat exchanger, focusing on identifying salt solidification inside the tubes when air is used on the shell side [

10].

1.2. Construction Materials Used in Molten Salt Therml Power Systems

Molten salt reactors (MSRs) and other molten salt applications face significant material challenges due to the high temperatures and corrosive nature of the salts. Molten salts have been proposed for use as heat transfer fluid and thermal energy storage for concentrating solar power (CSP) plants. They have low melting points, low viscosities, high boiling points, and high specific heat. However, these molten salts are highly corrosive, especially at the high temperatures (they may cause hot corrosion). In most high-temperature corrosive environments, alloys derive their corrosion resistance by forming a stable protective oxide film on the surface of the materials. These protective oxide films are soluble and chemically unstable in molten salts. Without the protection of oxide film, alloy elements are attacked by dissolution in molten salt. Moreover, thermal creep, corrosion fatigue and Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC) are also concerns at high temperatures and in corrosive environments [

11,

12,

13]. Crofer 22 is a high-temperature ferritic stainless steel developed primarily for use in environments where oxidation resistance and thermal stability are critical, such as in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs). This alloy forms a stable chromium oxide layer, which reduces chromium evaporation and contributes to its corrosion resistance in high-temperature environments [

14]. Crofer

®22H is a ferritic stainless steel with a chemical composition of approximately 20–24% chromium (Cr), with Iron (Fe) as the balance, and minor amounts of other elements like Manganese (Mn), Silicon (Si), Aluminum (Al), Titanium (Ti), and trace amounts of Carbon (C) [

15]. Its melting temperature is about 1500–1530 °C [

15].

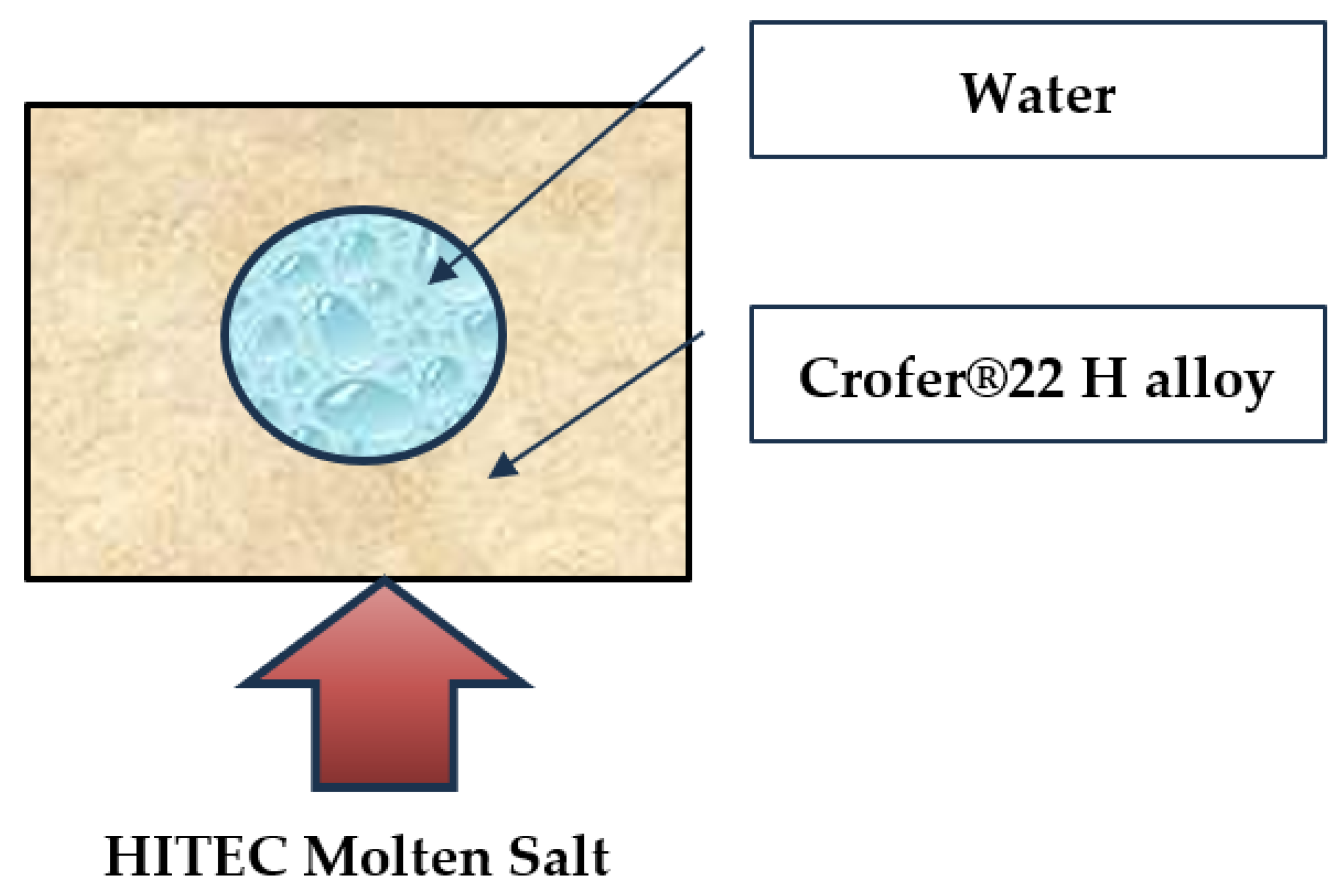

1.3. Scope and Novelties of This Research

In the framework of this research, a fully coupled computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation model of the HITEC molten salt cooling system has been developed. It simultaneously solved the Turbulent Navier–Stokes, and energy and heat conduction transport, equations. This fully coupled study examined the HITEC molten salt cooling system without using a convective coefficient (conjugate heat transfer method). The conjugate heat transfer (CHT) approach solve the fluid and solid equations simultaneously at the interface to exchange heat directly. This method has several advantages. It provides a high-fidelity result by solving the heat transfer problem across both the fluid and solid (conduction). The main configuration is a cylindrical tube along which water flows, surrounded by a solid block composed of a heat-resistant material (Crofer

®22 H alloy). This system is shown in

Figure 1.

To the best of my knowledge, this work is the first fully coupled CFD simulation of a water-cooling system based on HITEC and Crofer®22 H alloy. The proposed geometrical configuration of this heat exchanger is also novel.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Thermo-Physical Properties of the Crofer®22H

The thermal conductivity of Crofer

®22 H as a function of temperature is provided in

Figure 2. The data has been taken from [

15].

The density of Crofer

®22H at room temperature is 7700 [kg/m

3]. It should be noted that the proposed heat exchanger may work in temperature ranges higher than 500 °C. It is possible to use, for example, chloride molten salt. Mixtures containing chlorides like NaCl, MgCl

2, and KCl can operate from 385 °C to 800 °C [

16]. Its specific heat as a function of the temperature is shown in

Figure 3. The data has been taken from [

15].

2.2. Thermo-Physical Properties of the HITEC Molten Salt

The density of HITEC is shown in

Figure 4 and is adapted from [

6].

The thermal conductivity of HITEC is shown in

Figure 5 and is adapted from [

6].

The average heat capacity of HITEC molten salt is 1424 [J/(kg * K)] [

6]. Based on these thermo-physical properties, the Prandtl number of HITEC molten salt has been calculated (it is a dimensionless quantity that represents the ratio of a fluid’s momentum diffusivity to its thermal diffusivity) by the following equation:

The Prandtl number of the HITEC molten salt is shown

Figure 6.

2.3. Geometry of the Molten Salt Water Cooling System

Figure 7 shows the geometry of this system.

The water-cooling system consists of a tube and a shell. The tube radius is 5 mm, and its length is 200 mm (0.2 m). The system width is 14 mm. The pipe diameter, d, is 0.01 m. Its height is 12 mm.

2.4. Coupling CFD and Thermal Simulations of the HITEC Molten Salt Water Cooling System

This section describes numerical analysis of the heat exchanger system. COMSOL finite element code has been employed in this work.

In the framework of this research, the turbulent fluid flow and thermal effects are coupled without using a convective coefficient. This method is based on the conjugate heat transfer (CHT) approach.

2.4.1. Governing Transport (Turbulent Fluid Flow, Continuity and Energy) Equations

The governing equations numerically solved are as follows:

- (a)

Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) and continuity equations. Wilcox (k-ε) turbulence model applied in the tube domain.

- (b)

Convective heat transfer equation in the tube domain.

- (c)

Heat conduction equation in the Crofer22®22 H domain.

Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations are a set of momentum transport equations used in fluid dynamics to model the behavior of turbulent flows. The Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) method is a widely used approach in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for modeling turbulent flows. Instead of directly simulating all the complex, time-dependent fluctuations of turbulence (as in Direct Numerical Simulation—DNS), RANS equations provide a time-averaged representation of the flow. The foundation of RANS is the Reynolds decomposition. In this technique, an instantaneous flow variable (like velocity or pressure) is decomposed into two parts: the mean component and the fluctuating component. To solve the RANS equations, the Reynolds stresses must be modeled in terms of the known mean flow quantities. This is the role of turbulence models. Numerous turbulence models of varying complexity and accuracy have been developed. They are typically based on empirical observations, physical reasoning, and mathematical simplifications. A common category of RANS turbulence models includes Two-Equation Models. These are very popular in engineering applications and are used to solve two additional transport equations for two turbulence quantities. Common examples include the k-ϵ (k-epsilon) and k-ω (k-omega) models.

The characteristic of a flow is often described by the Reynolds number, which is defined as

where

U is the water velocity flowing inside the tube and d is the tube diameter,

ρ is the water density, and

η is the water viscosity. The water inlet velocities,

U, for the two cases are 1 m/s and 10 m/s. The numerical values of the Reynolds numbers are 10,000 and 100,000, respectively. These Reynolds are greater than 2100 [

17,

18]. Thus, it is possible to use a turbulence model. The k-ε model is often applied in turbulence models. This turbulence model introduces the turbulent kinetic energy,

k, and the dissipation rate of turbulence energy, ε. The turbulent viscosity is modeled by [

19,

20]

is a model constant. The transport equation for

k is [

19]

The transport equation for

ε is [

14,

15]

The turbulent model constants in the above equations are determined from experimental data [

13]. Their values are listed in

Table 1.

The RANS (Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes) turbulence models are widely used in engineering (especially in CFD) because they are fast and reasonably accurate for many practical flows. But they definitely have some important limitations: Many RANS models (especially simple ones like k-ε, k-ω) assume turbulence is isotropic (i.e., same in all directions). However, real turbulence, specially near walls, in swirling flows, or in shear layers—is often highly anisotropic. It should be noted that RANS equations are time-averaged; they smooth out important transient phenomena like vortices, turbulence bursts, or oscillations. This means they cannot capture transient phenomena without extra modeling (e.g., URANS or switching to LES). It is justified to use RANS for pipe flow for fully developed turbulent flow (constant velocity profile along the pipe length) and simple geometries (such as straight pipes and moderate curvature). Engineering-level accuracy is acceptable (not super high-fidelity details). The continuity transport equation is [

19]

The energy equation applied of the water flowing inside the tube is as follows [

19]:

The heat conduction equation of the Crofer

®22 H is

2.4.2. Boundary Conditions and Initial Conditions

It is assumed that the velocity of the water entering the channel is 1 m/s and 10 m/s. The temperature of the water entering into the tube is 20 °C. It is assumed that the bottom side of the Crofer

®22H block is heated by the HITEC molten salt. It is assumed that the velocity of the molten salt over the plate is 20 m/s. The Reynolds number of HITEC molten salt is shown in

Figure 8.

The Reynolds numbers of HITEC molten salt shown in

Figure 8 are much greater than the critical Reynolds number for a flat plate. Thus, it is possible to apply Chilton-Colburn empirical equation in order calculate the Nu number [

21]:

The forced convective heat transfer coefficient and the molten salt temperature are constant and uniform. The rest of the other boundaries are defined adiabatic.

The convective heat transfer coefficient as a function of the temperature is shown in

Figure 9. It has been assumed that the convective heat transfer coefficient is 18,173 W/(m

2·K) and the molten salt temperature is

.

The maximal value of the HITEC molten salt convective coefficient is greater than 18,000 [W/(m

2·K)]. Similar convective heat transfer coefficients have been reported in [

22]. In general, radiative heat transfer is negligible in molten salts under turbulent flow conditions [

23,

24].

3. Results

The influence of the water velocity on the cooling system performance has been investigated in this research. The numerical results for a water velocity of 1 [m/s] are presented in

Section 3.1. Grid sensitivity analysis has been carried out. This numerical model has been validated against analytical results. The numerical results for water velocity of 10 [m/s] are presented in

Section 3.2.

3.1. Numerical Simulation Results for Case I

The model geometry contains 2 domains, 12 boundaries, 24 edges, and 16 vertices. The mesh consists of 792,172 domain elements, 44,132 boundary elements, and 1772 edge elements. The convergence plot is shown in

Figure 10.

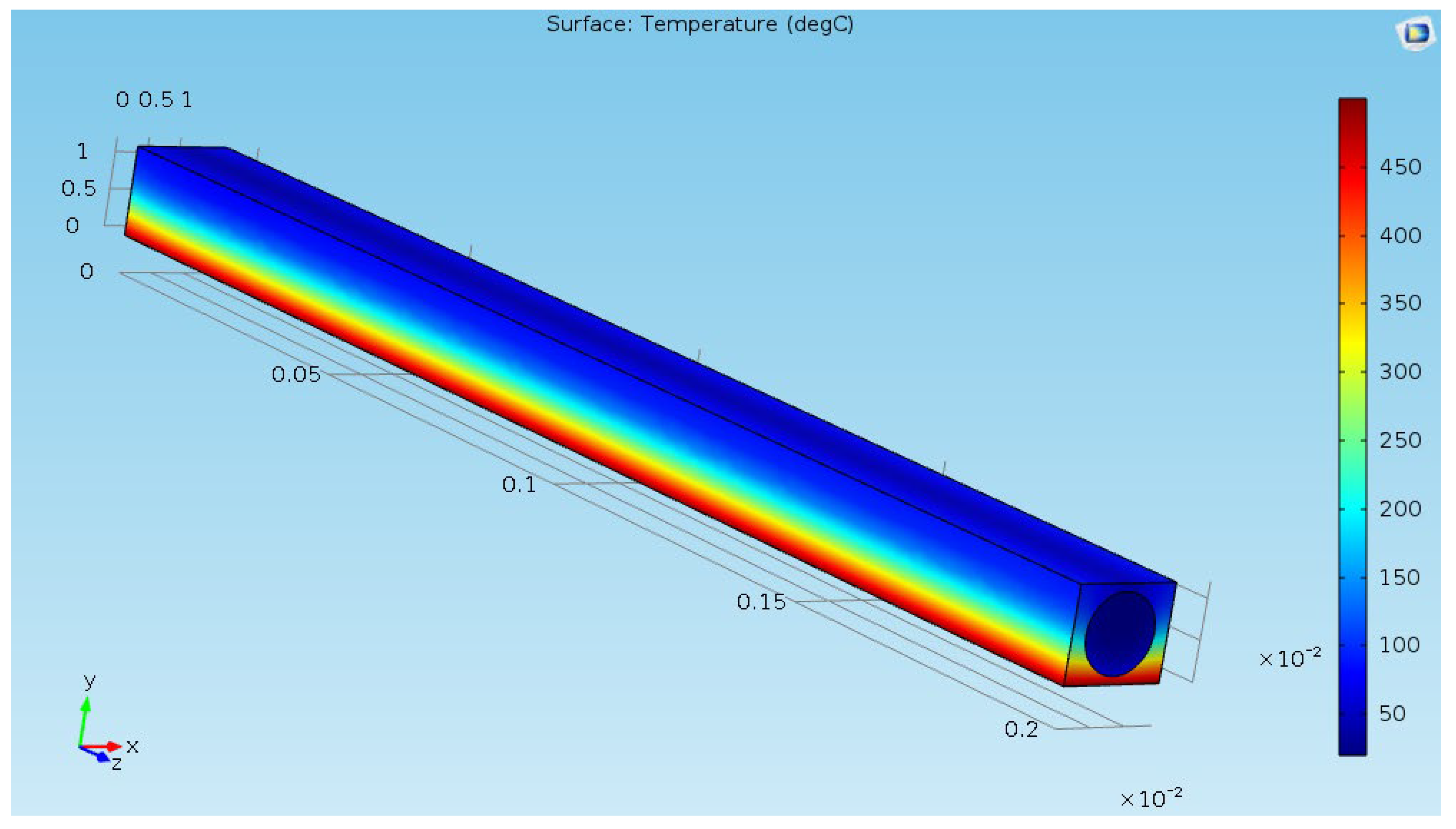

Figure 10 shows that the numerical errors have been decreased by 5 magnitudes. A 3D temperature field of the water flowing inside the tube is provided in

Figure 11.

Figure 11 shows that the maximal surface temperature of the Crofer

®22H reached 500 °C. A large temperature gradient is observed on the Crofer

®22H. It is less than the maximal service temperature of Crofer

®22H, which is typically up to 900 °C [

25]. The average outlet water temperature as a function of the time is provided in

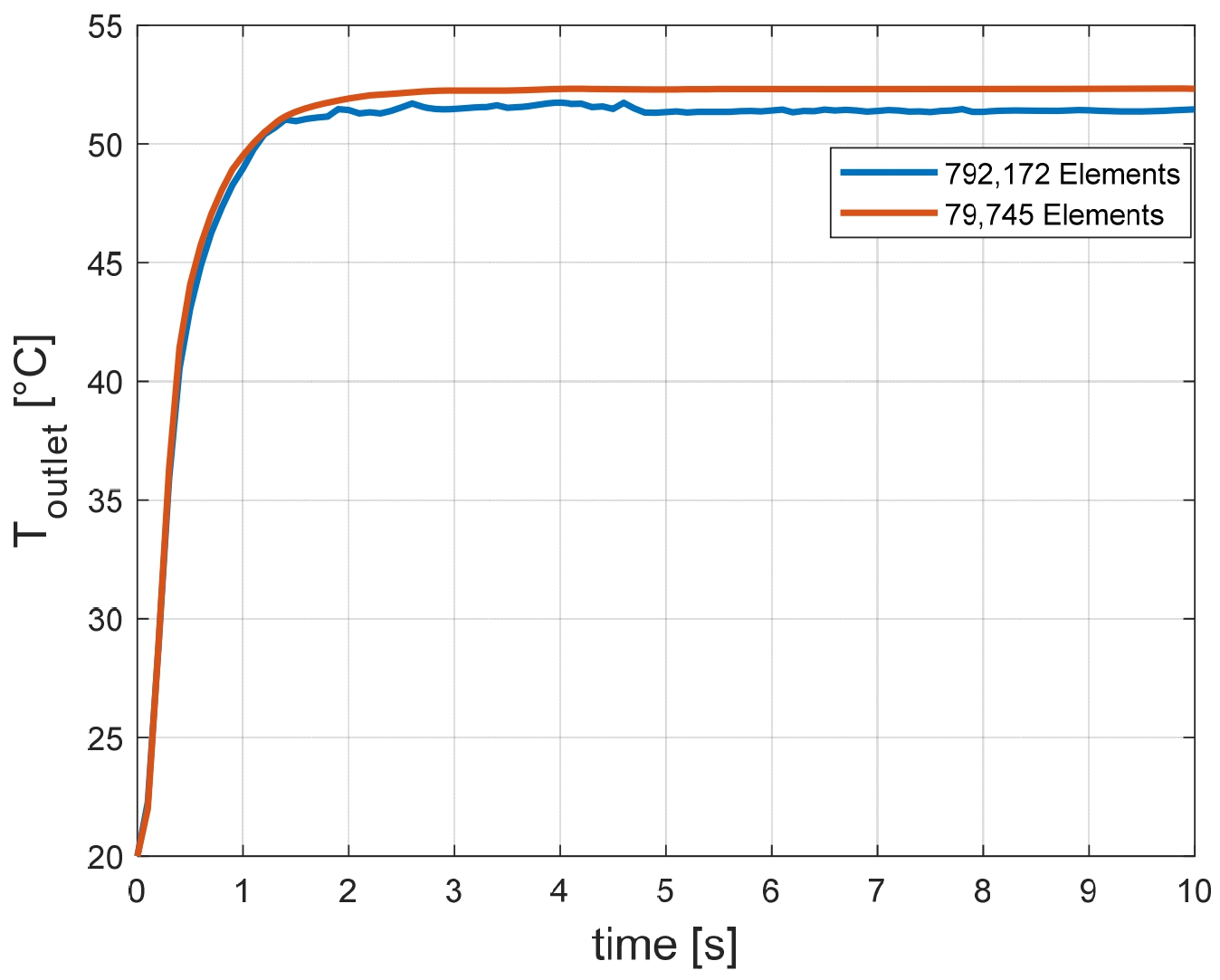

Figure 12.

Figure 11 shows that the average outlet water temperature reached a steady state value of 51.5 °C after 2 s. Two simulations have been performed on two COMSOL models. The first simulation has been performed with mesh consisting of 792,172 domain elements, 44,132 boundary elements, and 1772 edge elements. The second simulation has been performed with mesh consisting of 79,745 domain elements, 15,838 boundary elements, and 1033 edge elements. The difference in the average temperature is less than 2% (see

Figure 13).

The average surface temperature as a function of the time is provided in

Figure 14.

The average surface temperature reached 377 °C (the metal is hot at the two sides of the solid block). As can be seen from the graph shown in

Figure 9, the convective heat transfer coefficient is about 18,174 W/(m

2·K). The heat transfer results obtained by using COMSOL software version 5.1 have been validated against analytical results. A closed-form solution has been obtained for constant heat flux. It should be noted that the radiative heat transfer is negligible in molten salts under turbulent flow conditions. The analytical solution for this case is obtained by using an energy balance equation at steady state conditions [

21].

where

h denotes the molten salt convective coefficient,

is the surface temperature,

is the molten salt temperature, P is the half perimeter of the circular water tube, L is the length of the heat exchanger.

and

are the mass flow rate and heat capacity of the water. The maximum difference between the analytical results and numerical results is less than 7% (the analytical solution for this case is 55.23 °C). The average outlet water temperature is less than the boiling temperature of the water at atmospheric pressure.

3.2. Numerical Simulation Results for Case II

The 3D velocity field of the water flowing inside the tube is provided in

Figure 15.

Figure 15 shows that the water flows with a fully developed turbulent velocity profile [

26]. A 3D temperature field of the water-cooling system is provided in

Figure 16.

Figure 16 shows that the maximal surface temperature reached 441.2 °C. This temperature is less than the temperature shown in

Figure 11. This is because the water mass flow rate is greater than in the previous case. It is less than the maximal service temperature of Crofer

®22H, which is typically up to 900 °C [

25].

4. Conclusions

Molten salt heat exchanger systems are primarily used in applications that benefit from high-temperature heat transfer and thermal energy storage.

Concentrated Solar Power (CSP): This is one of the most prominent applications. Molten salts are used to absorb solar energy during the day and store it as heat. This stored heat can then be used to generate electricity at night or on cloudy days, making solar power a more reliable, on-demand energy source.

Industrial Process Heating: Various industrial processes, such as chemical recycling and steel processing, require high temperatures. Molten salt systems can provide a stable and efficient way to deliver this heat, which is an alternative to traditional thermal oil or steam systems.

In the framework of this research work, a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation model of the HITEC molten salt water cooling system has been developed. HITEC molten salt is a specialized heat transfer and thermal energy storage medium primarily used in industrial processes and solar thermal power plants. It is a eutectic blend of sodium nitrate, sodium nitrite, and potassium nitrate. COMSOL finite element code has been employed in this work. In the framework of this research the conjugate heat transfer (CHT) method has been applied. This method provides a high-fidelity numerical result without making assumptions about the convective coefficient. It simultaneously solves the Turbulent Navier–Stokes and energy and heat conduction transport equations. This fully coupled study examined a HITEC molten salt cooling system. The main configuration is a cylindrical tube along which water flows, surrounded by a solid block composed of a heat-resistant material (alloy Crofer®22 H).

The governing equations numerically solved are as follows:

- (a)

The Wilcox (k-ε) turbulence model and continuity equations applied in the water tube domain.

- (b)

The convective heat transfer (energy) equation in the tube domain.

- (c)

The heat conduction equation is solved throughout the solid domain

A parametric study has been performed in order to analyze the influence of the water velocity on the water-cooling system performance, and two cases have been investigated in this paper: a water flowing velocity of 10 [m/s] and a water flowing velocity of 1 [m/s]. It has been observed that the maximal surface temperature of the Crofer®22 H reached 441.2 °C in the first case. The maximal surface temperature of the Crofer®22 H reached 500 °C in the second case. These values are less than the maximal service temperature of Crofer®22, which typically reaches up to 900 °C. Crofer®22 H provides excellent steam oxidation, high corrosion resistance, and high thermal creep resistance.

In the second case it has been shown that the average outlet water temperature reached the steady state value of 51.5 °C after 2 s. The heat transfer results obtained by using COMSOL software version 5.1 have been validated against analytical results. A closed-form solution has been obtained for constant heat flux. The maximum difference between the analytical results and numerical results is less than 7% (the analytical solution for this case is 55.23 °C). The proposed HITEC molten thermal system may be applied in oil and gas industries and in power plants (such as the Organic Rankine Cycle). It should be noted that the proposed heat exchanger may work in temperature ranges higher than 500 °C. It is possible to use, for example, chloride molten salt. Mixtures containing chlorides like NaCl, MgCl2, and KCl can operate from 385 °C to 800 °C. Typically, natural gas or oil is combusted on site to fuel steam generation units, which creates two problems. First, it exposes the project to economic risk through the highly variable nature of natural gas costs, which is significant given the large volume of fuel that will be consumed over the life of the project. Second, natural gas combustion is the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions for an in-situ project. Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) was demonstrated to be a practical and economically viable tool for heat generation. The exit temperatures of CSP or fluoride salt-cooled, high-temperature reactor (FHR) reactors meet most process heat requirements. The exit temperature is about 700 °C. Refinery peak temperatures reach ~600 °C (thermal crackers). The molten salt transfers the heat to water, which then heats the ORC’s working fluid. For example, the hot water can heat the Butane working fluid flowing in the boiler. Hot water is used extensively in oil refineries for both direct process applications and for auxiliary functions like cleaning and heating. The desalting process is a critical first step in refining hot water used to prepare crude oil for distillation.