Considering the impact of different critical parameters on the integrated system’s performance, three parameters are selected for sensitivity analysis in this section: pressure of HPT and pinch temperature difference in HEXs and P30 (the pre-expansion pressure of propane in the ORC). The pressure of HPT determines the pressure ratio of compressors and the stored energy level of CO2, thereby affecting both the charging and discharging efficiencies. Pinch temperature difference in HEXs influences the heat-recovery ability and thermal match between fluids, which are essential for high system efficiency. P30 strongly affects the expansion ratio, net power output, and exergy efficiency of the ORC subsystem. Since these three parameters directly determine the energy conversion, heat-utilization, and power generation performance of the integrated system, they are selected as the primary critical parameters for the sensitivity analysis.

4.2.1. The Effects of Pressure of HPT

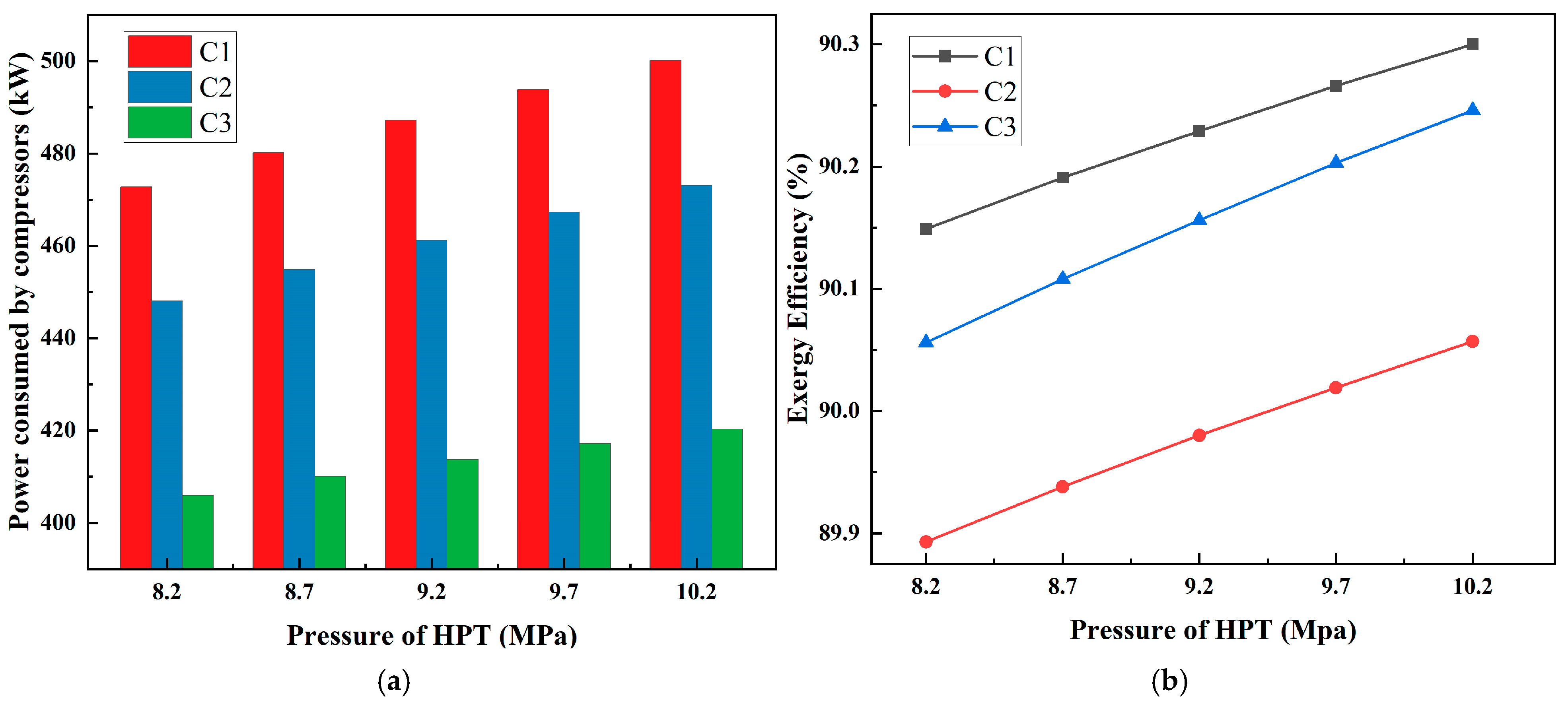

In this section, the pressure of HPT is selected to vary from 8.2 MPa to 10.2 MPa in the charge process of CCES system, as this range represents a practical operating interval that ensures stable CO2 storage while maintaining safe compressor and tank conditions.

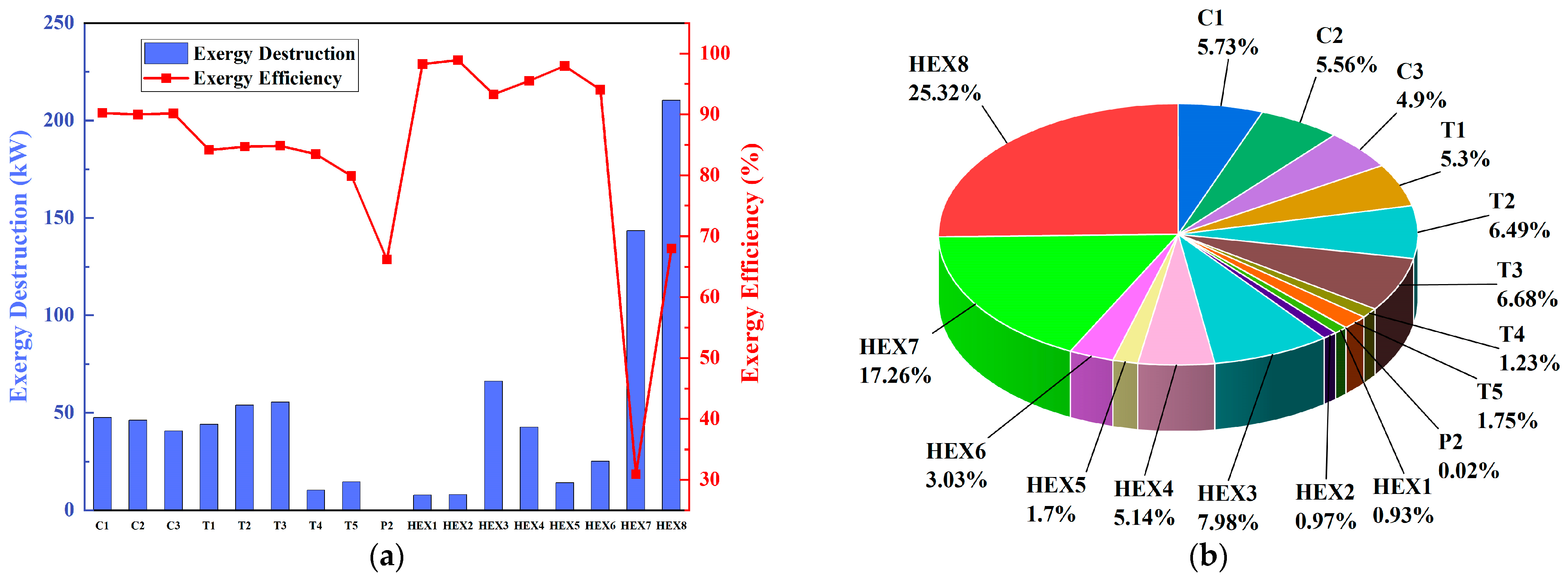

Figure 4 illustrates how the power consumption and exergy efficiency of three compressors (C

1, C

2, and C

3) vary under increasing pressure of HPT in the charge process of the CCES system. As shown in

Figure 4a, all three compressors show an increasing trend in power consumption as the pressure of the HPT rises from 8.2 MPa to 10.2 MPa. C

1 consistently shows the highest power consumption among all compressors and increase from 472.74 kW to 500.15 kW, C

2 displays moderate power consumption, in the middle range between C

1 and C

3 and increase from 448.06 kW to 473.07 kW. C

3 shows the lowest power consumption across all pressures and increase from 405.91 kW to 420.24 kW. This trend of increased power consumption is due to the compression line of the CCES, the pressure ratio of the three compressors keep increasing which requires more power consumption.

Figure 4b expresses the relationship between exergy efficiency and the pressure of HPT. Exergy efficiency of each compressor measures the effectiveness with which the compressor converts input energy into useful work. All compressors show an increase in exergy efficiency with increasing pressure of HPT. C

1 has the highest exergy efficiency among all compressors and shows a consistent increase from 90.14% to 90.30%. C

3 also shows an increase but lower than C

1, rising from 90.05% to 90.24%. C

2 displays the lowest exergy efficiency but also has a small increase from 89.89% to 90.05%. This suggests that as the pressure of HPT increases, although the energy demand is higher, the compressors operate more effectively in terms of converting input energy into useful output.

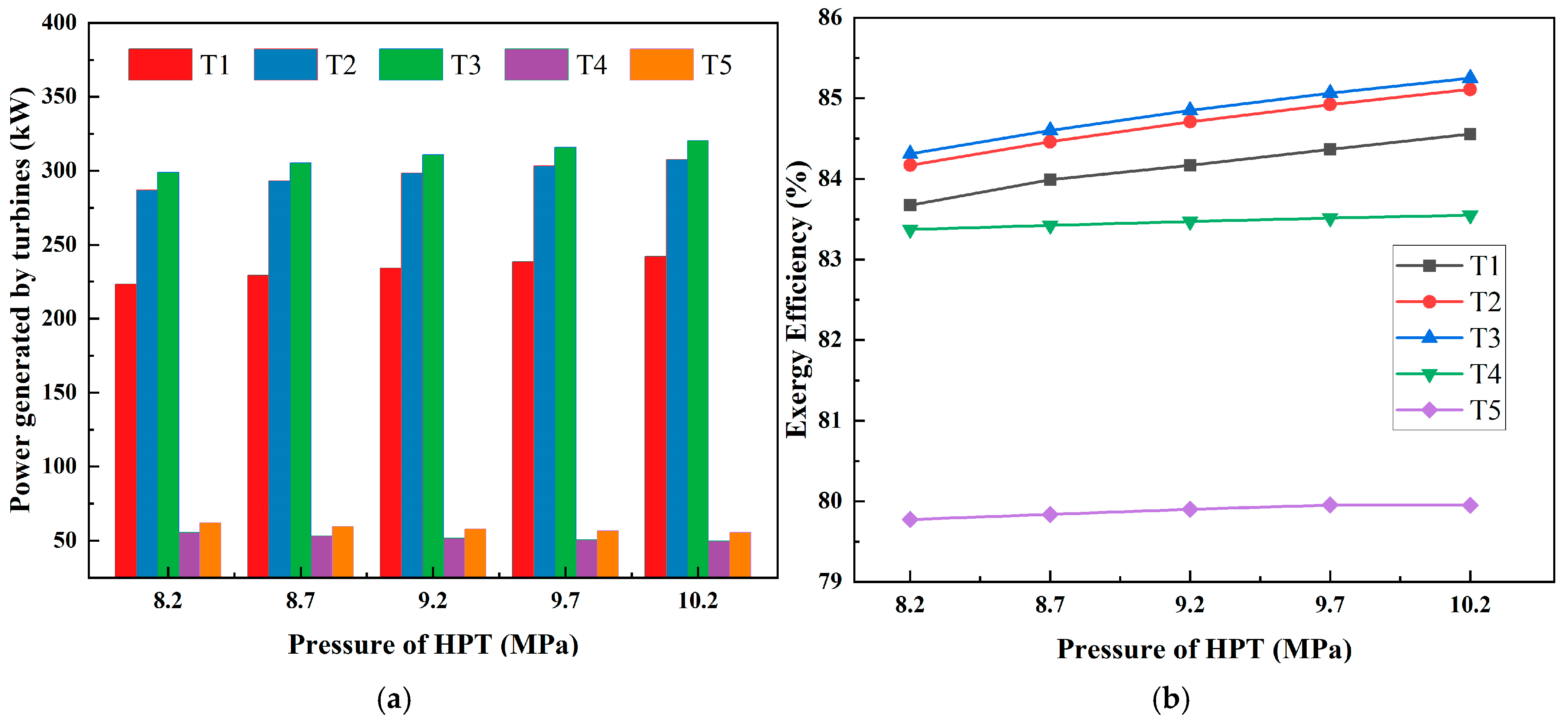

Figure 5 describes the power generation and exergy efficiency of five turbines (T

1 to T

5) under various pressures of HPT. As shown in

Figure 5a, T

1, T

2, and T

3 produce higher power compared to T

4 and T

5, with T

2 and T

3 producing the most. T

4 and T

5 produce significantly less power, especially noticeable at higher pressures since T

4 decreases from 55.42 kW to 49.69 kW and T

5 also decreases 62.03 kW to 55.50 kW, whereas T

1 increases from 223.31 kW to 242.11 kW, T

2 increases from 286.94 kW to 307.62 kW, and T

3 increases from 298.86 kW to 320.33 kW when the pressure of HPT rises. The upward trend in the power output of T

1, T

2, and T

3 can be explained by how, as the pressure of HPT increases, the heat absorbed by ethylene glycol during the compression process in CCES also increases, which in turn leads to an increase in the thermal energy that can be utilized by the turbines during the expansion process. The decrease in the power output of T

4 and T

5 is due to the outlet temperature of the hot fluid EG from HEX

7 in the ORC remaining unchanged (the temperature returned to CCES), which results in a decrease in the mass flow rate of propane in the ORC. The trend of each turbine of exergy efficiency under the increasing pressure of HPT is shown in

Figure 5b. T

1, T

2, and T

3 display a steady increase in exergy efficiency as the pressure of HPT rises, in which T

1 increases from 83.67% to 84.45%, T

2 increases from 84.17% to 85.11%, and T

3 increases from 84.31% to 85.25%, suggesting that these turbines are effectively converting available energy into useful work at higher pressure of HPT. T

4 and T

5 also shows an increase, but at a slower rate than T

1, T

2, and T

3, in which T

4 rises from 83.37% to 83.54% and T

5 rises from 79.77% to 79.95%, indicating less sensitivity to the pressure of HPT changes.

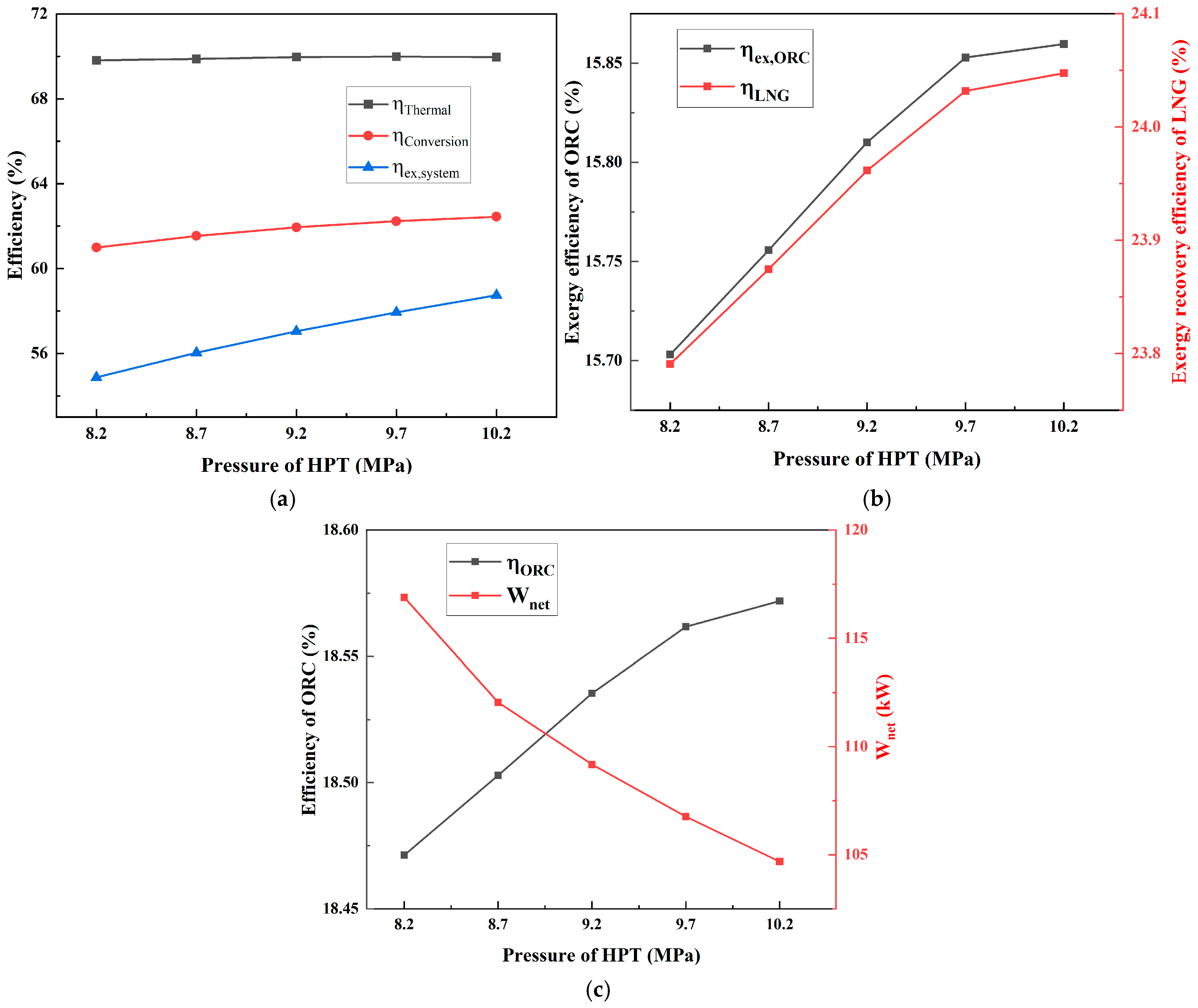

Figure 6 illustrates various efficiency metrics for the integrated system.

Figure 6a describes the relationship between the pressure of HPT and three different efficiency metrics (

,

and

). With the increase in pressure of HPT from 8.2 MPa to 10.2 Mpa,

is nearly constant, with very little variation of around 69.81% to 69.96%.

shows a steady increase from 60.98% to 62.44%, indicating improvements in the energy conversion process in the CCES system as the pressure of HPT increases.

also increases from 54.87% to 58.73%, which implies that the integrated system is becoming more effective at using the available energy to do work.

As shown in

Figure 6b, with the increase in pressure of HPT from 8.2 MPa to 10.2 Mpa,

gradually increases from 18.47% to 18.57%. This result indicates that the ORC system becomes more efficient in its energy conversion process under higher pressure of HPT. However,

shows a clear downward trend from 116.88 kW to 104.68 kW as the pressure of HPT increases, showing that while the system may be operating more efficiently, the output power available from the ORC system is less.

As shown in

Figure 6c,

and

raise simultaneously as the pressure of HPT rises.

increases from 15.70% to 15.86%, suggesting that ORC components are better utilizing the available thermal energy as the pressure of HPT increases. The increase of

(from 23.79% to 24.04%) indicates that the use of LNG in ORC for cooling is becoming more efficient under higher pressure of HPT.

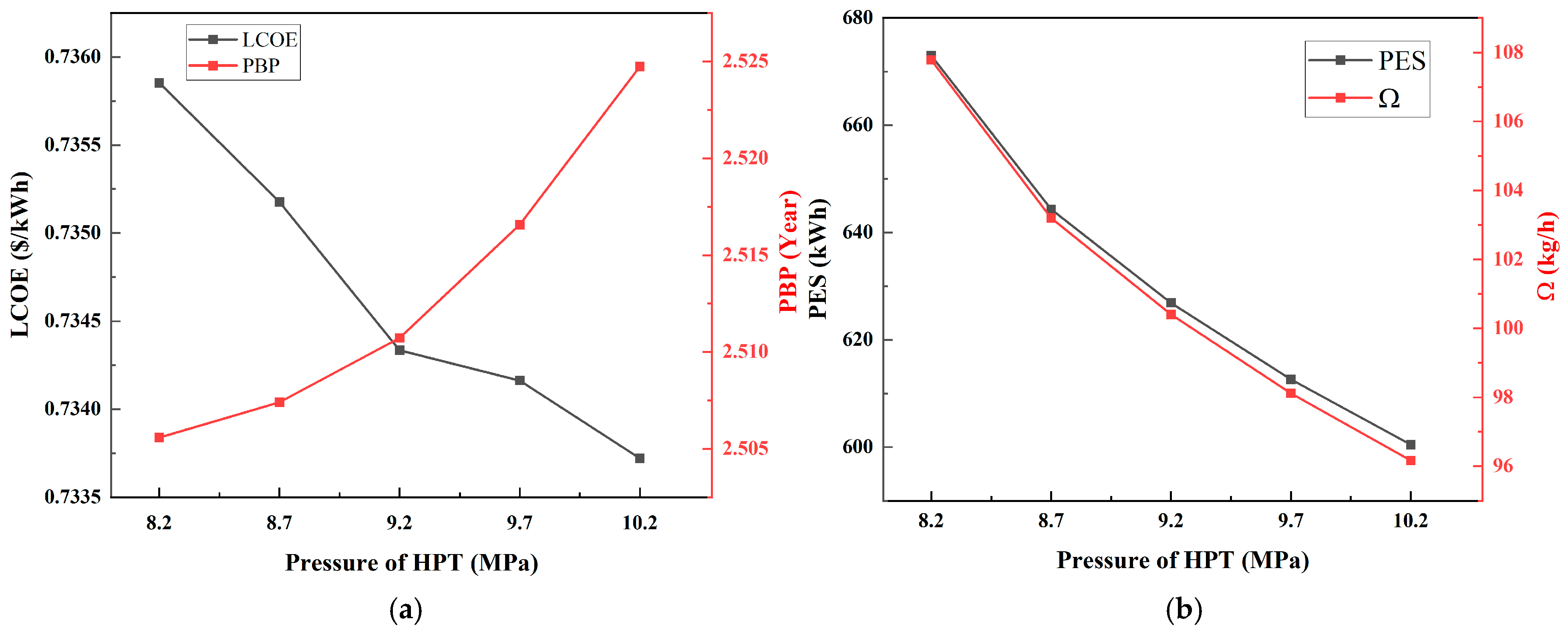

Figure 7a shows that integrated system economic performance varies under different pressure of HPT. LCOE decreases significantly from USD 0.7358/kWh to USD 0.7337/kWh as the pressure increases from 8.2 to 10.2 MPa, reaching a minimum value around 10.2 MPa, suggesting that higher pressure of HPT leads to less cost-effective electricity generation. PBP shows an increasing trend from 2.5 Years to 2.52 Years as the pressure rises, suggesting that the time to recover investments extends as pressure of HPT increases.

As shown in

Figure 7b, with the increase in pressure of HPT from 8.2 MPa to 10.2 Mpa, PES decreases consistently from 672.97 kWh to 600.46 kWh. This trend implies that the higher pressure of HPT makes the integrated system less efficient in terms of energy conservation and output per energy input.

decreases simultaneously from 107.78 kg/h to 96.17 kg/h since

decreased. In general, the decreasing trends in both PES and

at higher pressure of HPT indicate a decreasing trend in terms of environmental sustainability and efficiency.

In conclusion, increasing the pressure of HPT enhances thermodynamic performance (, and ) and slightly improves economic indicators (lower LCOE), but at the cost of reduced environmental benefits (lower PES and ) and slightly longer PBP. Therefore, the pressure of HPT represents a critical trade-off parameter in system design and optimization, and its optimal range must be carefully selected depending on the priority of performance metrics.

4.2.2. The Effects of Pinch Temperature Difference

In this section, to investigate the impact of different pinch temperature difference in HEXs on the system performance, four temperature values (3 K, 5 K, 7 K and 9 K) are selected as variables. In addition, the small pinch temperature differences represent idealized designs and may require additional constraints on the heat exchanger area and pressure drop in a detailed engineering-scale study.

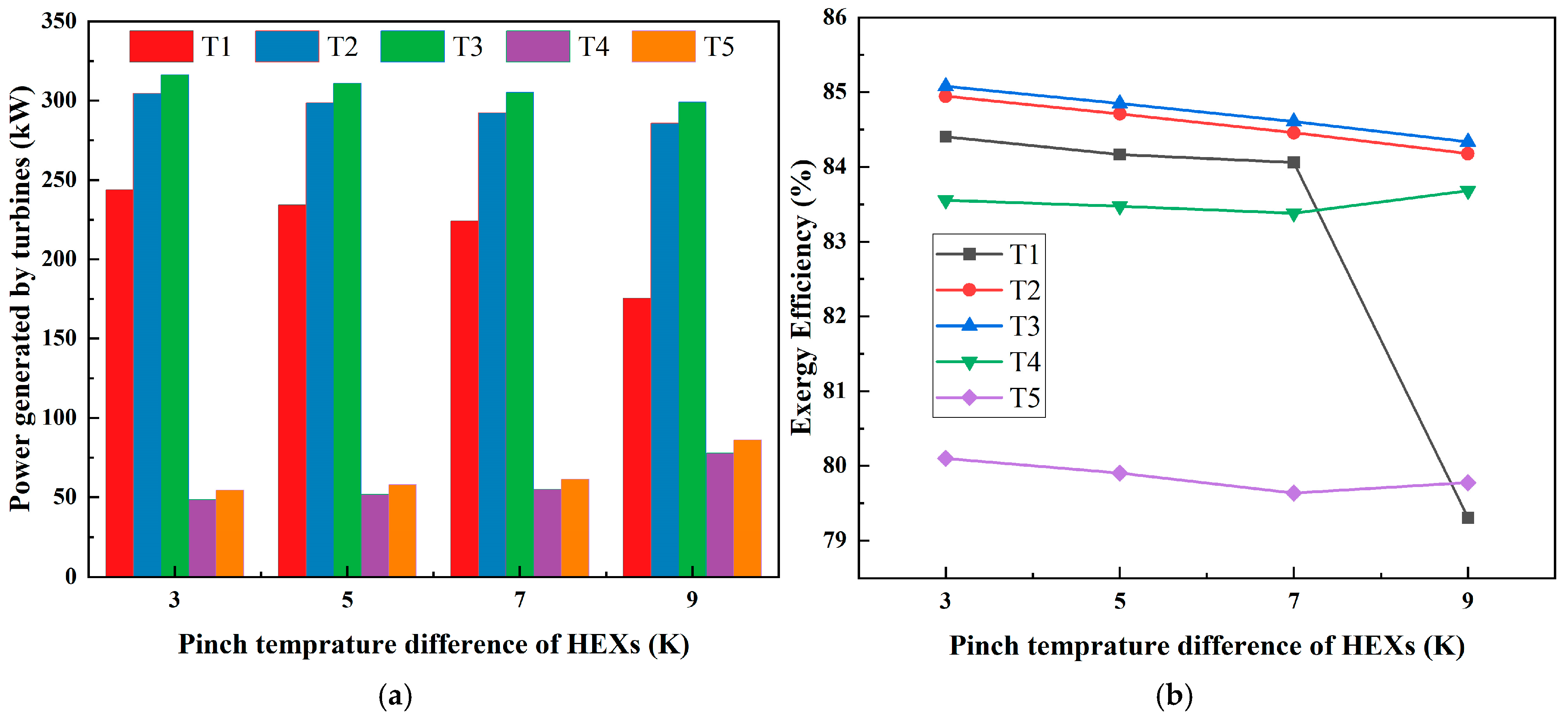

Figure 8 illustrates the power generation and exergy efficiency of five turbines (T

1 to T

5) under various pinch temperature differences in HEXs. As shown in

Figure 8a, turbines in the charge process (T

1, T

2, and T

3) show a decreasing trend of power generation with rising pinch temperature difference from 3 K to 9 K. T

1 reduces from 243.7 kW to 175.47 kW and drops dramatically when pinch temperature difference increases to 9 K, which is similar to the exergy efficiency in

Figure 8b. T

2 and T

3 have similar power generation; T

2 decreases from 304.54 kW to 285.67 kW and T

3 decreases from 316.31 kW to 299.07 kW. In contrast to the turbines of the charge process, T

4 and T

5 rise simultaneously as the pinch temperature difference rises. T

4 increases from 48.57 kW to 77.85 kW and T

5 increases from 54.46 kW to 86.06 kW. The decrease in the power output of T

1-T

3 is due to the increasing HEXs’ pinch temperature difference, which leads to a reduction in the heat transfer, and the amount of heat available for the turbines to utilize also decreases. The increase in HEXs’ pinch temperature difference leads to an increase in the propane mass flow in the ORC. As a result, the power output of T

4 and T

5 show an upward trend.

As shown in

Figure 8b, with the increase in pinch temperature difference from 3 K to 9 K, the exergy efficiency of T

1, T

2, and T

3 all decrease; while T

3 has the highest exergy efficiency and decreases from 85.07% to 84.33%, T

2 has a similar decreasing trend with T

3, from 84.94% to 84.17%. T

1 shows a noticeable decrease as pinch temperature difference increases, particularly dropping at 9 K, from 84.40% to 79.30%. The exergy efficiency of T

4 and T

5 are lower than turbines in the charge process, especially that of T

5, showing the lowest exergy efficiency among all turbines from 80.1% to 79.77%, and lowest exergy efficiency is reached when pinch temperature difference is 7 K. T

4 shows a simultaneous trend with T5 of exergy efficiency from 83.55% to 83.68%, which also reaches the lowest exergy efficiency when pinch temperature difference is 7 K.

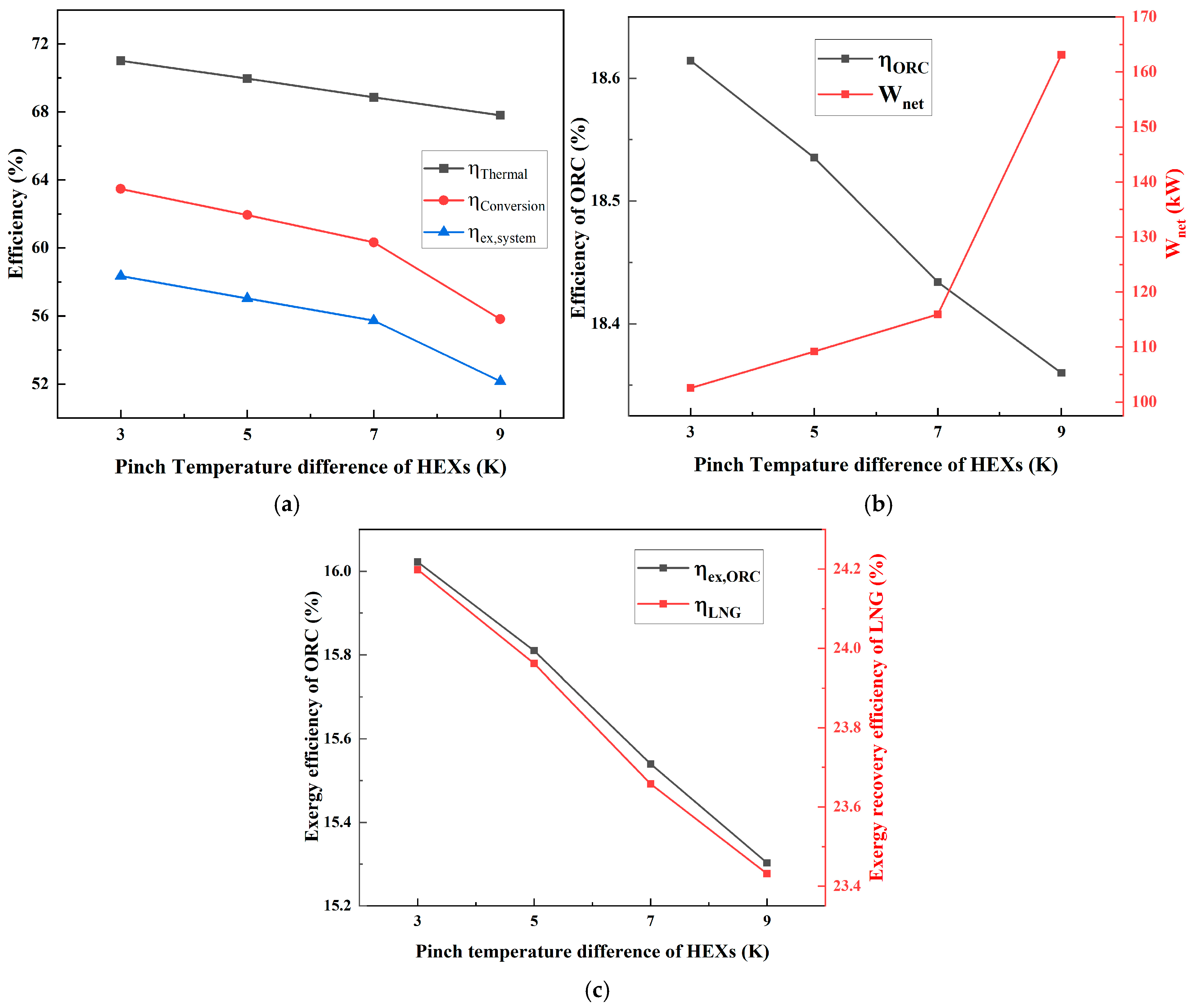

Figure 9 illustrates different efficiency metrics of the integrated system under different pinch temperature differences in HEXs. As shown in

Figure 9a,

remains relatively stable as the pinch temperature difference increases from 3 K to 9 K, only slightly decreasing from 71.01% to 67.80%. This stability suggests that

is less sensitive to variations in pinch temperature difference.

decreases significantly from 63.47% to 55.81% as the pinch temperature difference increases, suggesting that higher pinch temperature difference negatively affects the energy conversion process, due to the reduced thermal driving force.

also shows a notable decrease from 58.34% to 52.15% with higher pinch temperature difference. This indicates increasing inefficiencies and energy losses in the system as the pinch temperature difference in HEXs increases. A larger pinch temperature difference causes less heat transfer, which results in less energy recovery and conversion and ability of the integrated system to utilize available energy and exergy also declines as energy losses rise with less heat transfer.

As shown in

Figure 9b,

decreases from 18.61% to 18.36% with increasing pinch temperature difference, suggesting that the ORC becomes thermodynamically less efficient, as less heat exchange leads to less effective energy conversion. Contrary to the trend of

,

initially increases with increasing pinch temperature difference but then sharply rises at the highest pinch temperature difference from 102.53 kW to 163.12 kW.

As shown in

Figure 9c,

and

show a simultaneously downward trend under different pinch temperature of HEXs’ rises.

decreases steadily from 16.02% to 15.3% as pinch temperature rise which indicates that lower pinch temperature is more favorable for energy conversion process.

consistently decreases from 24.19% to 23.43% with higher pinch temperature difference. This further confirms that energy efficiency in such thermal process is compromised at higher pinch temperature due to low effective heat transfer.

Therefore, the performance improvement achieved by reducing the pinch temperature difference in HEXs can be regarded as the expected upper limit value of the performance enhancement that can be systematically achieved in the design of HEX7 and HEX8 by adopting advanced heat transfer technologies.

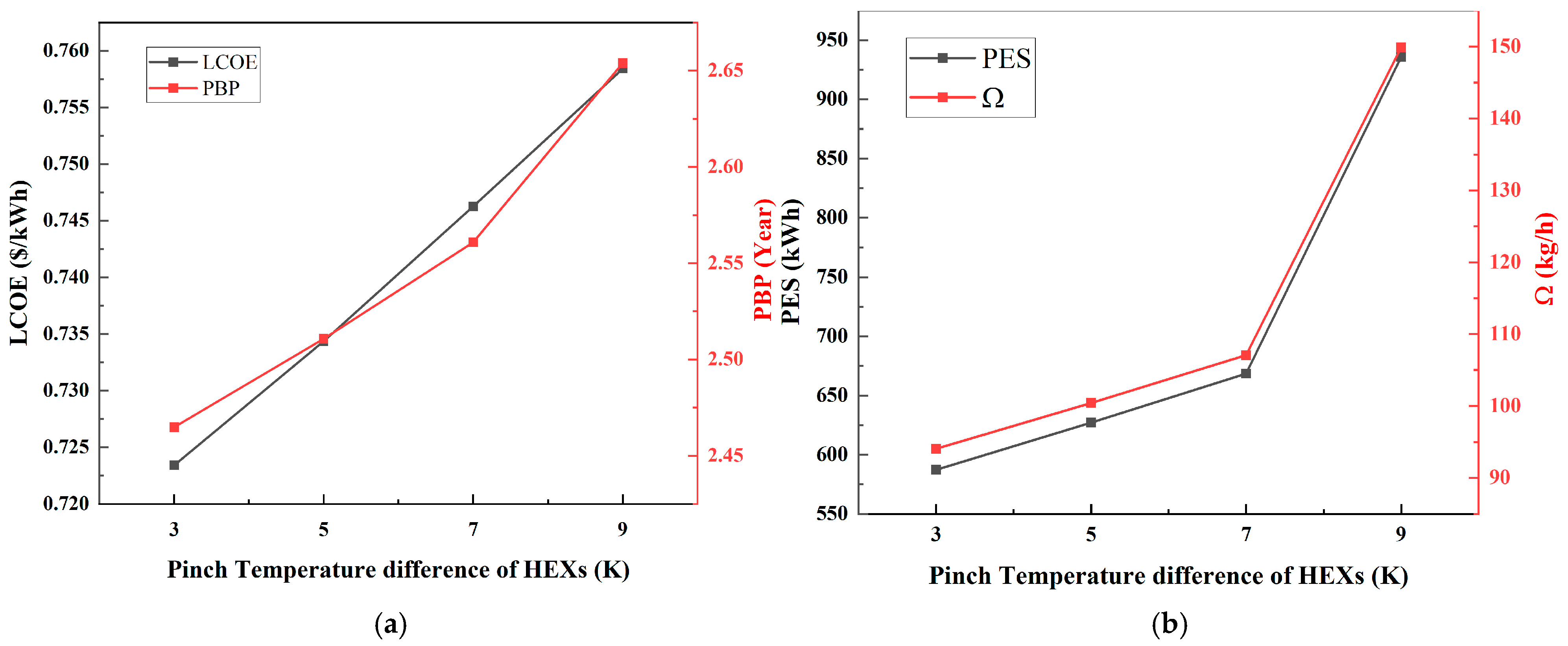

Figure 10 illustrates how pinch temperature difference in HEXs affects the economic and environmental performance of the integrated system. As shown in

Figure 10a, LCOE shows a clear upward trend as the pinch temperature difference increases from 3 K to 9 K. The rising LCOE from USD 0.723/kWh to USD 0.758/kWh indicates that larger pinch temperature difference reduces heat transfer effectiveness, leading to lower system efficiency and thus higher electricity generation cost. PBP also increases from about 2.45 years to 2.65 years as the pinch temperature rises. This suggests that system investment is recovered more slowly when thermal transfer is poorer.

Figure 10b describes the environmental performance of the integrated system. There is a notable jump in PES as the pinch temperature difference increases, rising sharply from around 587.22 kWh to 935.92 kWh. This increase suggests that the energy saving of the integrated system becomes better at higher pinch temperature difference. This trend is consistent with

. Another environmental metric of

Ω similarly shows a steep increase from about 94.04 kg/h to 149.89 kg/h. This reflects that despite lower thermal efficiency, the system could be effectively offsetting more CO

2 at higher pinch temperature difference.

In conclusion, these results show a complex interaction between economic cost, environmental impact, and system efficiency as influenced by the pinch temperature difference in HEXs. Higher pinch temperature difference, while negative to cost-effectiveness and basic thermal performance, enhances other aspects like energy savings and avoided CO2 emissions. These insights could be critical for making decisions about operating parameters and optimization of the integrated system.

4.2.3. The Effects of P30

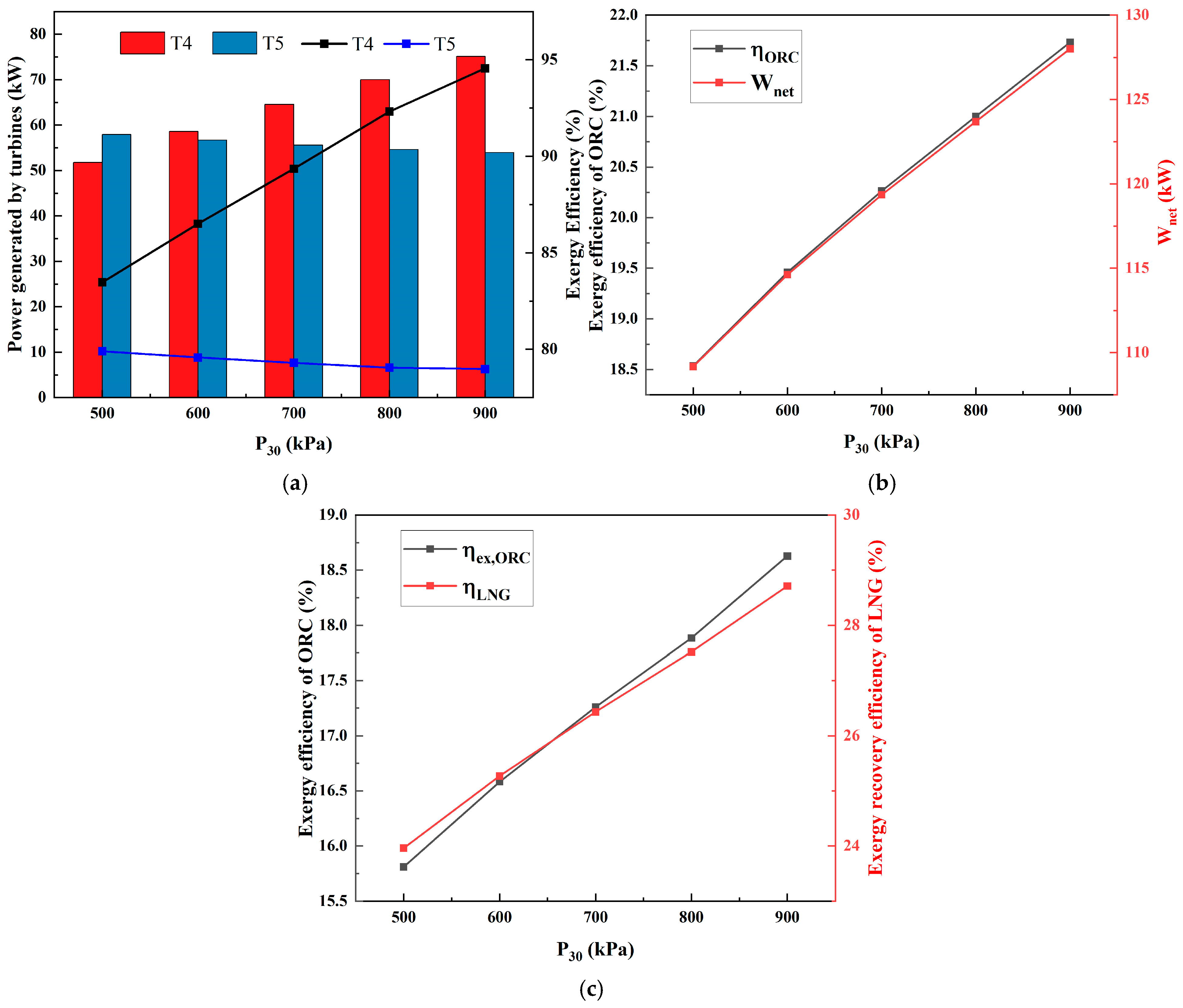

Figure 11 illustrates the influence of P

30 (the pre-expansion pressure of propane in the ORC) on the performance of turbines and ORC system efficiency. As shown in

Figure 11a, with P

30 rising from 300 kPa to 900 kPa, the power output of T

4 increases significantly from 51.78 kW to 75.10 kW; exergy efficiency of T

4 also increases steadily from 83.47% to 94.55%. This result indicates that T

4 performs better at higher propane initial pressure. On the contrary, the power output of T

5 decreases from 57.93 kW to 53.96 kW; the exergy of T

5 also shows a slight downward trend from 79.90% to 78.98%, suggesting that T

5 is negatively affected by higher P

30. The decrease in the output power of T

5 is due to the drop in the outlet temperature of T

4 (the propane inlet temperature of HEX

8), which leads to a reduction in heat exchange, further causing the outlet temperature and mass flow rate of LNG at HEX

8 to decrease, resulting in a reduction in the available heat for T

5.

As shown in

Figure 11b, both

and

increase linearly and significantly with P

30 rising;

increases from 18.53% to 21.73% and

increases from 109.17 kW to 127.99 kW. Increasing P

30 increases the expansion ratio and specific work output in ORC, improving both efficiency and net power. This confirms that higher pre-expansion pressure of propane is favorable for the performance of the ORC system.

As shown in

Figure 11c,

and

both show a positive correlation with P

30.

increases from 15.81% to 18.62% and

increases from 23.96% to 28.71%. This is because the higher propane pressure increases the expansion work potential in the ORC system, reducing irreversibility and improving exergy utilization.

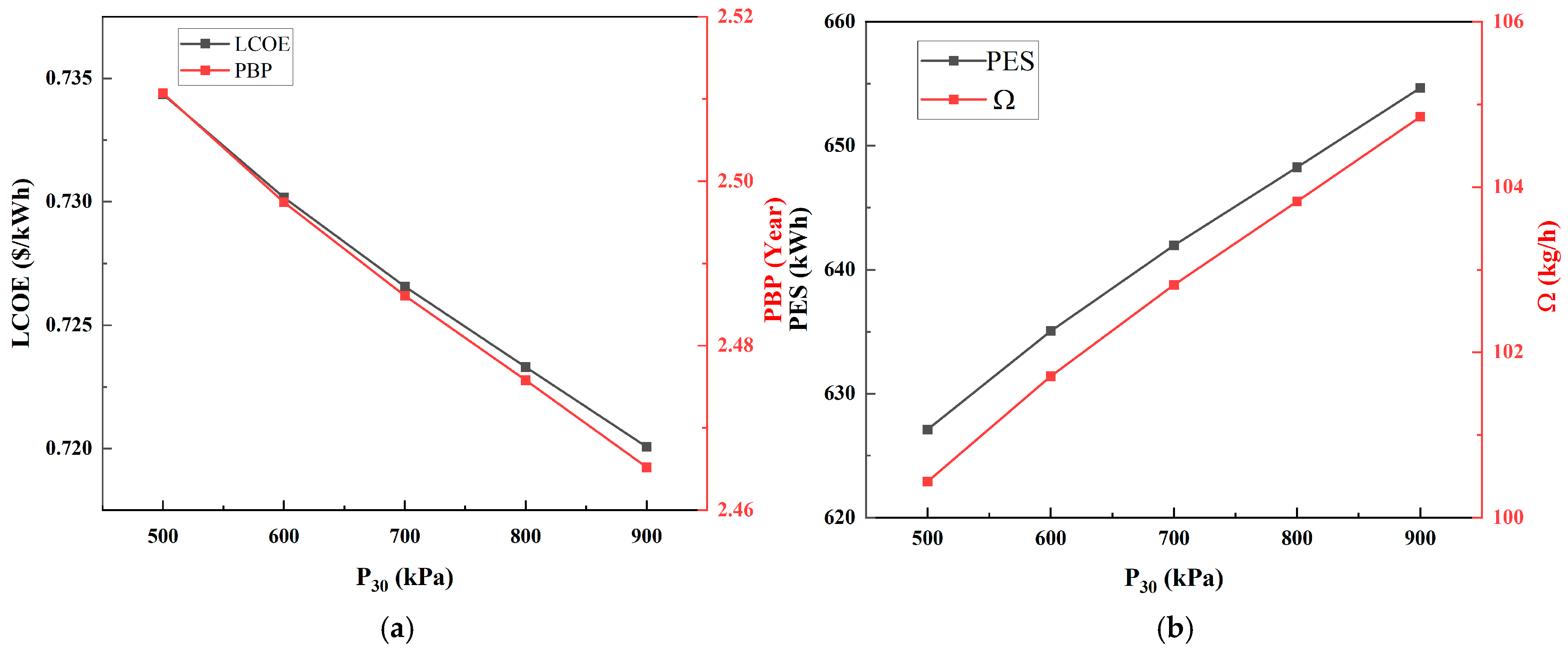

Figure 12 shows how the varying P

30 affects the economic and environmental performance of the integrated system. As shown in

Figure 12a, as P

30 increase from 500 kPa to 900 kPa, LCOE and PBP have a downward trend simultaneously. LCOE reduces from USD 0.734/kWh to USD 0.720/kWh and PBP reduces from 2.51 years to 2.46 years. This indicates economic improvement at higher propane pressure, due to an improved expansion ratio and reduced irreversibility. The ORC system becomes more efficient, leading to lower LCOE and PBP.

The environmental performance of integrated system under varying P

30 is shown in

Figure 12b. PES and Ω both show an upward trend as P

30 increases. PES rises from 627.09 kWh to 654.66 kWh and

Ω increases from 100.43 kg/h to ~104.85 kg/h. This is because higher P

30 improves energy conversion effectiveness, leading to greater substitution of fossil fuel-based power. As a result, more CO

2 emissions are avoided and PES is enhanced.

In general, increasing P30 significantly enhances the overall performance of the integrated system. As P30 rises, both thermal and exergy efficiencies improve, increases, and the system becomes more economically attractive with a lower LCOE and shorter PBP. Additionally, environmental benefits are improved, as shown by higher PES and Ω. Therefore, treating P30 as a key optimization parameter is an effective strategy to achieve high efficiency, economic viability, and environmental sustainability in system design and operation.