Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Particles in Exhaled Breath Condensate via Engineered Face Masks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. EBC Collection Device

2.2. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

2.3. Sample Collection and Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA

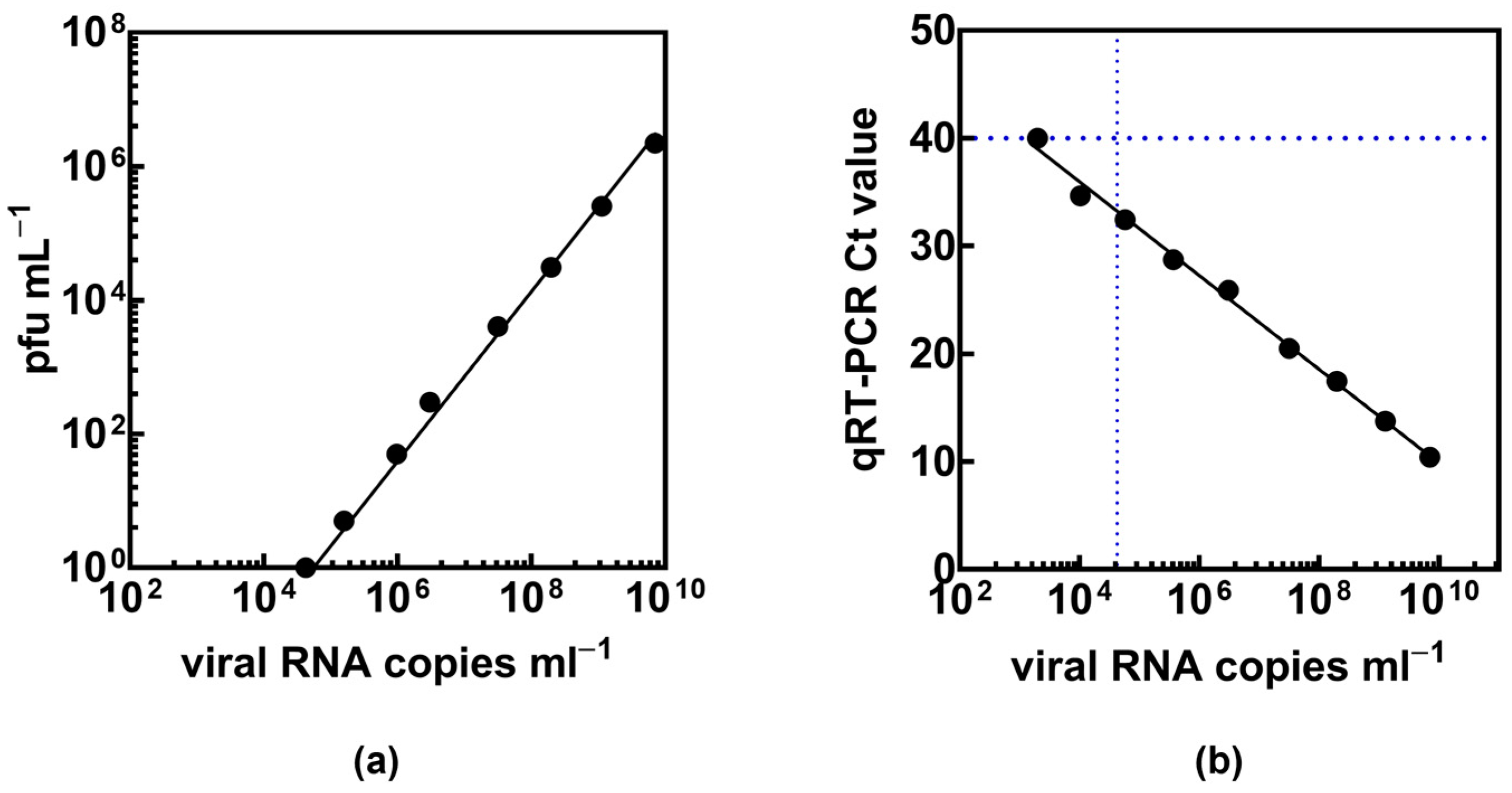

2.4. Biological Experiments

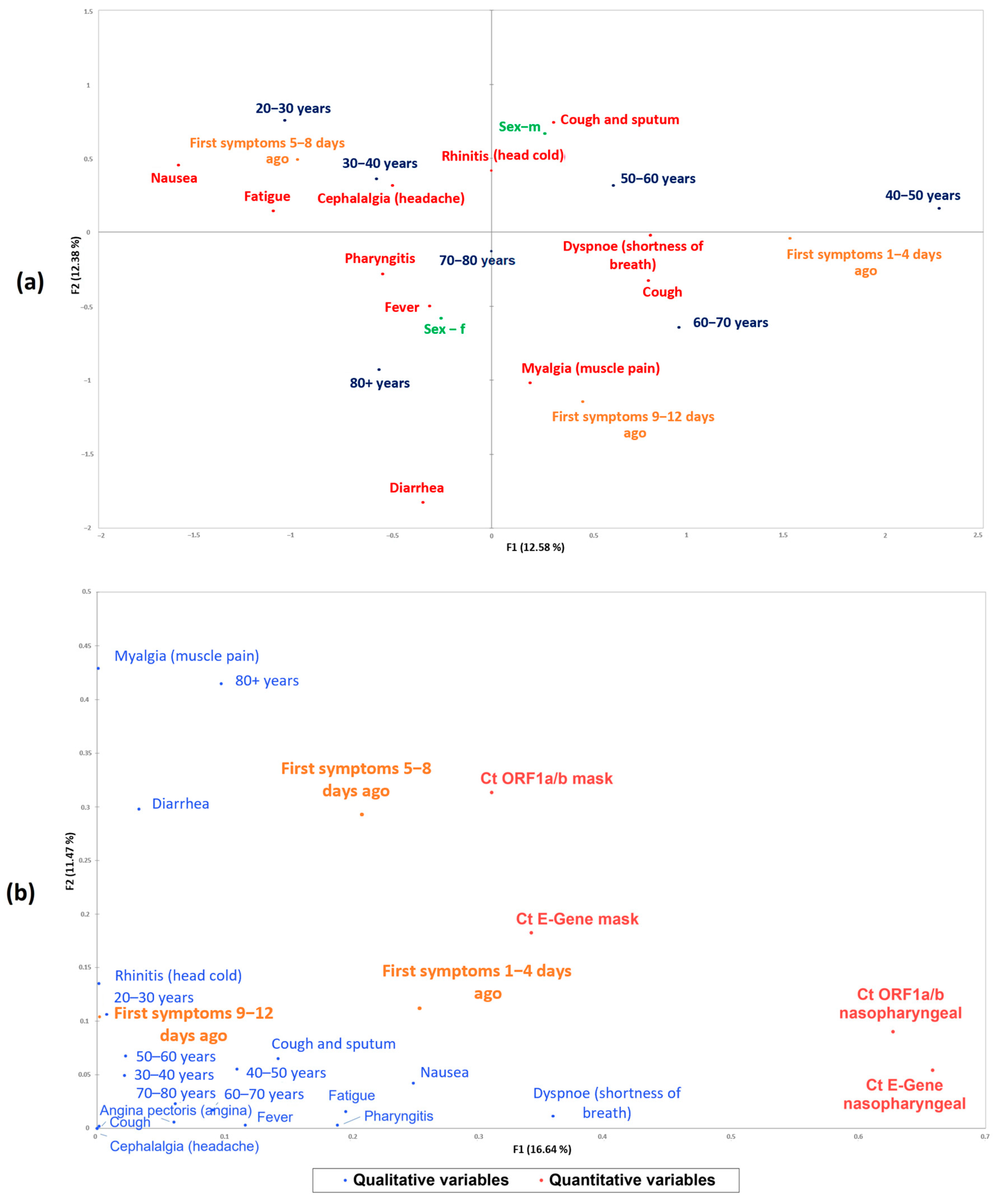

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meo, S.A.; Meo, A.S.; Klonoff, D.C. Omicron new variant BA.2.86 (Pirola): Epidemiological, biological, and clinical characteristics—A global data-based analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 9470–9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, D.; Palmer, J.C.; Tudge, I.; Pearce-Smith, N.; O’Connell, E.; Bennett, A.; Clark, R. Long distance airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: Rapid systematic review. BMJ 2022, 377, e068743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prather, K.A.; Marr, L.C.; Schooley, R.T.; McDiarmid, M.A.; Wilson, M.E.; Milton, D.K. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 370, 303–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almstrand, A.C.; Ljungström, E.; Lausmaa, J.; Bake, B.; Sjövall, P.; Olin, A.-C. Airway monitoring by collection and mass spectrometric analysis of exhaled particles. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, T.; Drikakis, D. On respiratory droplets and face masks. Phys. Fluid. 2020, 32, 063303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhang, R.; Li, J. Coughs and Sneezes: Their Role in Transmission of Respiratory Viral Infections, Including SARS-CoV-2. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 651–659. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, F.; Ozen, M.O.; Guimaraes, C.F.; Wang, J.; Hokanson, K.; Ahmed, R.; Reis, R.L.; Paulmurugan, R.; Demirci, U. Wearable Collector for Noninvasive Sampling of SARS-CoV-2 from Exhaled Breath for Rapid Detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 41445–41453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwanochie, E.; Linnes, J.C. Review of non-invasive detection of SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory pathogens in exhaled breath condensate. J. Breath Res. 2022, 16, 024002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J.; Wadekar, S.; DeCubellis, K.; Jackson, G.W.; Chiu, A.S.; Pagneux, P.; Saada, H.; Engelmann, I.; Ogiez, J.; Loze-Warot, D.; et al. A mask-based diagnostic platform for point-of-care screening of COVID-19. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 192, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleiro Rufo, J.; Paciencia, I.; Mendes, F.C.; Farraia, M.; Rodolfo, A.; Silva, D.; de Oliveira Fernandes, E.; Delgado, L.; Moreira, A. Exhaled breath condensate volatilome allows sensitive diagnosis of persistent asthma. Allergy 2019, 74, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank-Quinn, C.; Armstrong, M.; Powell, R.; Gomez, J.; Elie, M.; Reisdorph, N. Determining the presence of asthma-related molecules and salivary contamination in exhaled breath condensate. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeminasab, S.; Ghanbari, R.; Emamalizadeh, B.; Jouyban-Gharamaleki, V.; Taghizadieh, A.; Jouyban, A.; Khoubnasabjafari, M. Exhaled breath condensate efficacy to identify mutations in patients with lung cancer: A pilot study. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2022, 41, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman-Beltran, S.; Carreto-Binaghi, L.E.; Carranza, C.; Torres, M.; Gonzalez, Y.; Munoz-Torrico, M.; Juarez, E. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Mediators in Exhaled Breath Condensate of Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. A Pilot Study with a Biomarker Perspective. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patsiris, S.; Papanikolaou, I.; Stelios, G.; Exarchos, T.P.; Vlamos, P. Exhaled Breath Condensate and Dyspnea in COPD. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1337, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.J.; Toomey, S.; Madden, S.F.; Casey, M.; Breathnach, O.S.; Morris, P.G.; Grogan, L.; Branagan, P.; Costello, R.W.; De Barra, E. Use of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Thorax 2021, 76, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhamsyah, R.; Dimandja, J.-M.D.; Hesketh, P.J. Design and Analysis of Exhaled Breath Condenser System for Rapid Collection of Breath Condensate. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.A.; Quindry, J.C. Application of a Novel Collection of Exhaled Breath Condensate to Exercise Settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szunerits, S.; Dӧrfler, H.; Pagneux, Q.; Daniel, J.; Wadekar, S.; Woitrain, E.; Ladage, D.; Montaigne, D.; Boukherroub, R. Exhaled breath condensate as bioanalyte: From collection considerations to biomarker sensing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, H.; Park, J.; Abbas, N.; Kang, S.; Hyun, H.; Seong, H.; Yoon, J.G.; Noh, J.Y.; Kim, W.J.; et al. Collection and detection of SARS-CoV-2 in exhaled breath using face mask. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Kan, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, Z.; Pan, W.; Zhou, F.; Duan, X. An intelligent face mask integrated with high density conductive nanowire array for directly exhaled coronavirus aerosols screening. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 186, 113286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshid, M.; Bakhshi Sichani, S.; Barbosa Estrada, D.L.; Neefs, W.; Clement, A.; Pohlmann, G.; Epaud, R.; Lanone, S.; Wagner, P. An Efficient Low-Cost Device for Sampling Exhaled Breath Condensate EBC. Adv. Sens. Res. 2024, 3, 2400020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Cheah, E.S.; Malkin, J.; Patel, H.; Otu, J.; Mlaga, K.; Sutherland, J.S.; Antonio, M.; Perera, N.; Woltmann, G.; et al. Face mask sampling for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in expelled aerosols. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.Q.; Soenksen, L.R.; Donghia, N.M.; Angenent-Mari, N.M.; de Puig, H.; Huang, A.; Lee, R.; Slomovic, S.; Galbersanini, T.; Lansberry, G.; et al. Wearable materials with embedded synthetic biology sensors for biomolecule detection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1366–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Buerer, L.; Wang, J.; Kaplan, S.; Sabalewski, G.; Jay, G.D.; Monaghan, S.F.; Arena, A.E.; Fairbrother, W.G. Efficient Detection of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from Exhaled Breath. J. Mol. Diagn. 2021, 23, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, L.K.; Casale, T.; Demoly, P. Coronavirus Disease (COVID)-19: World Health Organization Definitions and Coding to Support the Allergy Community and Health Professionals. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 2144–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.A.; Haefliger, S.; Harris, B.; Pavlakis, N.; Clarke, S.J.; Molloy, M.P.; Howell, V.M. Exhaled breath condensate for lung cancer protein analysis: A review of methods and biomarkers. J. Breath Res. 2016, 10, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.F.; Zhang, L.; Shi, S.Y.; Fan, Y.C.; Wu, Z.L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, D.Q. Expression of surfactant protein-A in exhaled breath condensate of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1667–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muccilli, V.; Saletti, R.; Cunsolo, V.; Ho, J.; Gili, E.; Conte, E.; Sichili, S.; Vancheri, C.; Foti, S. Protein profile of exhaled breath condensate determined by high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 105, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaria, M.; Mellors, T.R.; Petion, J.S.; Rees, C.A.; Nasir, M.; Systrom, H.K.; Sairistil, J.W.; Jean-Juste, M.-A.; Rivera, V.; Lavoile, K.; et al. Preliminary investigation of human exhaled breath for tuberculosis diagnosis by multidimensional gas chromatography—Time of flight mass spectrometry and machine learning. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2018, 1074–1075, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.-C.; Li, W.; Wu, L.; Huang, D.; Wu, M.; Hu, B. Solid-Phase Microextraction Fiber in Face Mask for In Vivo Sampling and Direct Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Exhaled Breath Aerosol. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11543–11547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canas, L.S.; Sudre, C.H.; Capdevila Pujol, J.; Polidori, L.; Murray, B.; Molteni, E.; Graham, M.S.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Berry, S.; et al. Early detection of COVID-19 in the UK using self-reported symptoms: A large-scale, prospective, epidemiological surveillance study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e587–e598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, I.M.; Alexander, H.D. Triple jeopardy in ageing: COVID-19, co-morbidities and inflamm-ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 73, 101494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

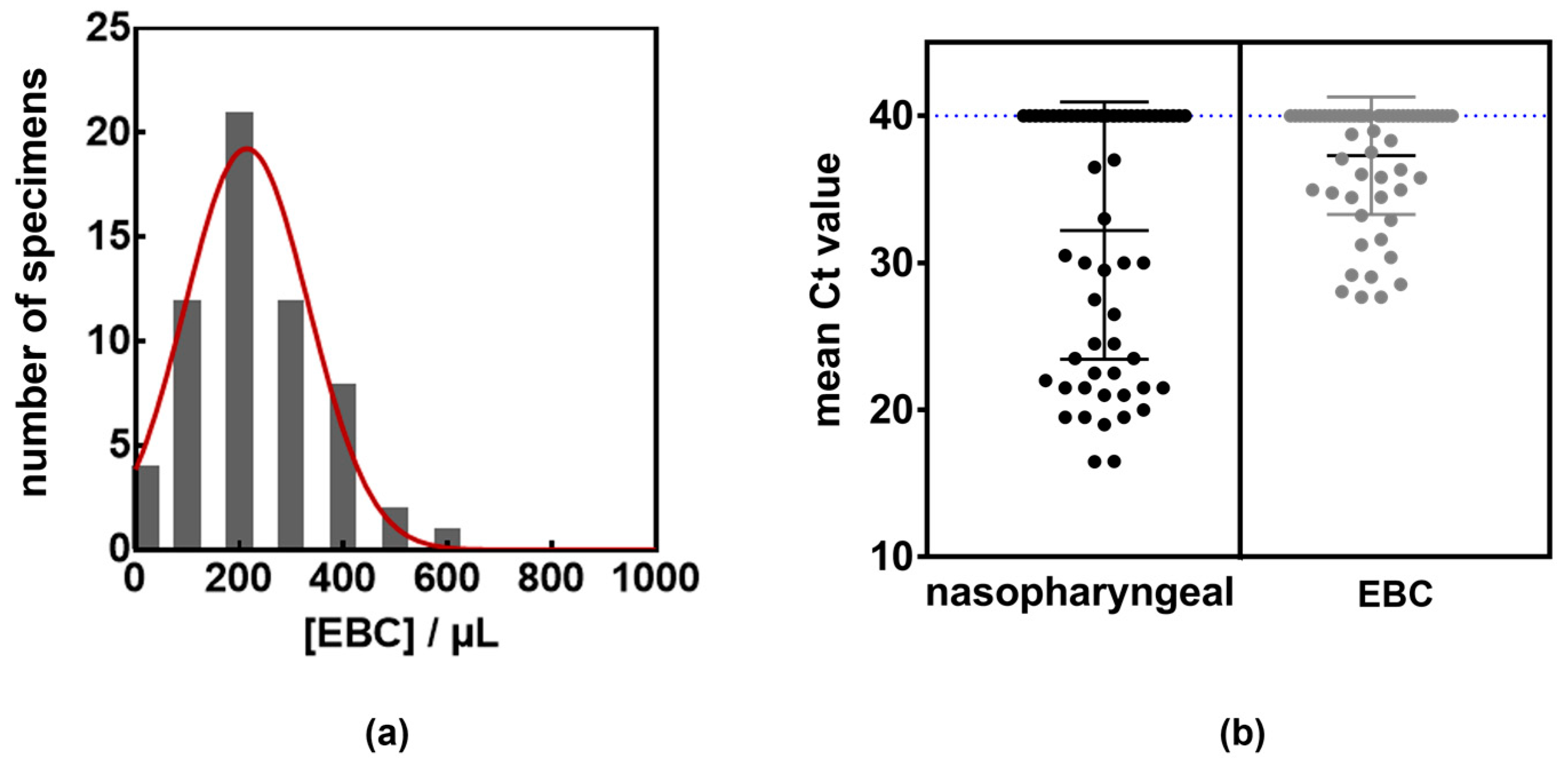

| Patient Characteristics | Total Cohort (n = 60) | Presence of Viral RNA in Nasopharyngeal Samples | Presence of Viral RNA in EBC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 32 females, 28 males | 30/30 (16 females, 14 males) | 25 */30 (16 females, 14 males) | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| Median | 27 | 71 | 65 | ||

| Mean | 45.7 | 66.2 | 63.4 | ||

| Average time from COVID-19 symptoms onset to test (days) | 6.7 | 6.7 | 4.7 | ||

| Nasopharyngeal sampling | EBC/mask sampling | ||||

| ORF1a/b | E-gene | ORF1a/b | E-gene | ||

| Sensitivity | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.8 | |

| Specifity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Positive predictive value | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Negative predictive value | 1 | 1 | 0.91 | 0.83 | |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| Accuracy | 1 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.9 | |

| Hospitalized Patient No. | Age (Years) | Ct ORF1a/b Nasopharyngeal | Ct E-Gene Nasopharyngeal | Ct ORF1a/b EBC (Mask) | Ct E-Gene EBC (Mask) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | 30.4 | 30.5 | 36.3 | 38.8 |

| 2 | 83 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 30.7 | 31.8 |

| 3 | 36 | 25.0 | 26.0 | 28.7 | 29.4 |

| 4 | 83 | 22.0 | 22.6 | - | - |

| 5 | 58 | 19.1 | 19.6 | 32.4 | 34.0 |

| 6 | 77 | 24.6 | 25.4 | 27.6 | 28.5 |

| 7 | 75 | 19.6 | 20.7 | 34.7 | 37.0 |

| 8 | 83 | 22.8 | 23.4 | - | 37.5 |

| 9 | 89 | 19.5 | 20.3 | - | - |

| 10 | 71 | 36.1 | 37.9 | - | - |

| 11 | 62 | 22.2 | 23.1 | 28.1 | 29.0 |

| 12 | 71 | 29.8 | 32.0 | 34.0 | 35.5 |

| 13 | 88 | 29.2 | 30.9 | 36.6 | - |

| 14 | 42 | 16.4 | 17.1 | 29.1 | 29.2 |

| 15 | 80 | 30.5 | 31.9 | - | - |

| 16 | 57 | 21.1 | 22.2 | 27.3 | 28.1 |

| 17 | 74 | 22.2 | 22.7 | 34.3 | 35.6 |

| 18 | 66 | 21.7 | 22.4 | 33.1 | 35.8 |

| 19 | 38 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 31.0 | 32.2 |

| 20 | 92 | 19.1 | 19.2 | 35.8 | 38.4 |

| 21 | 64 | 26.6 | 27.4 | 34.2 | 35.8 |

| 22 | 61 | 21.8 | 21.8 | 27.4 | 27.9 |

| 23 | 24 | 19.9 | 20.3 | 32.4 | 33.5 |

| 24 | 53 | 20.1 | 20.4 | 30.3 | 30.4 |

| 25 | 63 | 23.8 | 24.2 | 34.0 | 34.9 |

| 26 | 82 | 29.6 | 30.5 | 36.0 | 36.7 |

| 27 | 75 | 24.9 | 25.4 | 34.9 | 37.2 |

| 28 | 51 | 39.9 | 34.7 | 34.7 | 36.9 |

| 29 | 77 | 32.7 | 34.5 | - | - |

| 30 | 90 | 27.4 | 28.3 | - | 37.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dörfler, H.; Daniels, J.; Wadekar, S.; Pagneux, Q.; Ladage, D.; Greiner, G.; Assadian, O.; Boukherroub, R.; Szunerits, S. Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Particles in Exhaled Breath Condensate via Engineered Face Masks. LabMed 2024, 1, 22-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010005

Dörfler H, Daniels J, Wadekar S, Pagneux Q, Ladage D, Greiner G, Assadian O, Boukherroub R, Szunerits S. Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Particles in Exhaled Breath Condensate via Engineered Face Masks. LabMed. 2024; 1(1):22-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleDörfler, Hannes, John Daniels, Shekhar Wadekar, Quentin Pagneux, Dennis Ladage, Georg Greiner, Ojan Assadian, Rabah Boukherroub, and Sabine Szunerits. 2024. "Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Particles in Exhaled Breath Condensate via Engineered Face Masks" LabMed 1, no. 1: 22-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010005

APA StyleDörfler, H., Daniels, J., Wadekar, S., Pagneux, Q., Ladage, D., Greiner, G., Assadian, O., Boukherroub, R., & Szunerits, S. (2024). Molecular Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Particles in Exhaled Breath Condensate via Engineered Face Masks. LabMed, 1(1), 22-32. https://doi.org/10.3390/labmed1010005