Abstract

Evidence-based practice in nursing supports clinical practice. Several studies have tested the knowledge and attitudes of nurses toward journal clubs (JCs) and evidence-based practice. However, no study has reported knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence-based practice (EBP) and journal club workshops in Oman whilst attending highly structured workshops with the aim of critiquing the method. This study aims to assess the knowledge of and attitude towards evidence-based practice (EBP) and JC sessions among nurses attending the EBP/JC workshop at Royal Hospital, Oman. Data were collected from 22 nurses who participated in the workshop through an online self-report validated questionnaire that examined knowledge, attitude, and satisfaction. The knowledge among the participants showed improvement after the EBP intervention (p = 0.002). There was no statistical difference (p = 0.33) between the pretest and post-test attitudes towards EBP. The indicators suggest that the workshop with the highest mean value (4.14 out of 5 points), followed by the EBP workshop, which is helpful for clinical practices (mean value = 4.09), should continue in the future. The participants of the EBP workshop also agreed that they would recommend others for similar workshops. Research and EBP workshops can increase nurses’ knowledge and effectively engage them in EBP activities. Care should be given to the organization of the workshops as it directly influences the level of satisfaction. Nurses who are satisfied with EBP workshops are more likely to recommend them to others and maintain their future attendance.

1. Introduction

Evidence-based practice (EBP) plays a crucial role in the improvement of patients’ outcomes and general health quality [1]. It also empowers nurses and enhances their performance in patient care [1]. There are several strategies to promote EBP. These strategies include journal clubs, utilizing agents of change, teaching, and using mentors [2]. Journal club is a form of EBP where healthcare workers meet and discuss research articles linked to their clinical practice [3]. It has been used as an attractive option for nursing students to attain clinical hours because the practice allows nursing students to implement and lead a traditional in-person journal club or an online collaborative journal club [4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) encourages nurses to identify, apply, and appraise research that can improve the quality of health [1]. Health research is essential to improving health system performance and to the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) and the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [5]. However, the ultimate benefit of health research lies in its translation into strategies, technologies, policies, and interventions that are effectively and appropriately delivered to benefit the people, in particular the poor and other vulnerable groups. In many countries in the Western Pacific Region, the reality is that health policies are seldom well-informed by research evidence. This is either because the evidence base on many topics is inadequate or because the capacity for health research is limited to begin with [6]. EBP can improve other aspects, including positive attitudes toward research knowledge; involvement in research activities; authority to change patient care procedures; support from physicians, managers, and other staff; information-seeking behavior; career development plans; and educational level [2]. Moreover, journal clubs can improve the clinicians’ teamwork and the growth of professionals, providing power to the team and building the team [2].

Literature Review

In the medical field, journal clubs have been implemented for a long time. In contrast, nursing research has only been included in academic programs for the past twenty years, and journal clubs were recently introduced into the nursing practice [2]. It is documented that journal clubs were utilized to facilitate research in 1990 by reviewing and discussing research papers, giving evidence that journal clubs are a successful intervention in supporting nursing EBP [1]. The positive impact of journal clubs has improved professional’s and nurses’ awareness of recent evidence in research studies. Moreover, applying research in clinical practice has been promoted, demonstrating the effectiveness of structured journal clubs.

In Oman, the Royal Hospital’s (RH) goal 6 is “Promoting Continuous professional development, research, and innovation”, which involves initiating a culture of knowledge translation and expecting all nurses in the nursing department to undertake this goal to apply EBP in their units by 2030. In 2020, the nursing research section of the RH initiated a journal club in the nursing department, where the nurses’ mentors were called to participate on a monthly basis to present and appraise a research paper with a group of nurses. The informative journal club aimed to deliver an interactive session for nurses and eventually discuss the applicability and utilization of best evidence [1,2].

Studies have shown that journal clubs improve participants’ familiarity with research studies and enhance their skills in reading and critically appraising information, thereby promoting the dissemination of research knowledge [2]. Nurses reported that participation in accessible journal clubs contributed to positive outcomes; they became more skilled, engaged, and fostered a safer environment within their workplaces. Moreover, implementing nursing journal clubs enabled nurses to better comprehend and apply research findings in clinical practice [1]. Experiences gained from journal paper discussions also contributed to enhanced nursing performance and the effective application of evidence-based practice (EBP) [1]. Some studies further suggested that engaging in evidence appraisal helped nurses develop greater self-confidence in their knowledge and clinical skills, as well as the ability to engage in knowledge sharing and promote practice changes [7]. Online sessions were also found to be effective even when nurses were away from their workplaces during educational activities [8].

Several factors influence the successful implementation of journal clubs [2]. Key factors include strong guidance from individuals with pedagogical, clinical, and research competencies, fostering a positive environment, and encouraging participants’ active engagement in the planning process. In addition, well-structured meetings and consistent attendance by participants are essential [2]. Participation in journal clubs can be facilitated by recognizing them as part of career development initiatives and integrating them within the organization’s research programs, allowing employees to attend during working hours [2,3]. To further strengthen clinical research teams, institutions are encouraged to establish clinical practice guidelines for procedures, organize targeted training programs, and develop unit-based council committees within critical care services [3]. However, certain barriers may impede the implementation of journal clubs, including limited planning time, workload constraints, inappropriate selection of research papers, and technical issues during virtual sessions [2].

Similarly to other change initiatives, evidence-based practice (EBP) implementation presents several challenges for nurses [1]. A primary barrier is the scarcity of human resources, with limited staff available to meet the increasing demands of healthcare services. Additionally, access to relevant literature, whether through physical libraries or electronic databases, is often restricted due to journal subscription limitations and associated costs. These barriers have contributed to gaps in the application of EBP and a growing disconnect between academic literature and nursing practice [1]. Although EBP has been studied in Oman since 2017 and a knowledge gap was identified [9], prior research primarily utilized cross-sectional designs without evaluating the impact of educational interventions on nurses’ knowledge and attitudes. In contrast, the current study adopts a different approach by examining changes in knowledge and attitudes resulting from participation in structured educational sessions. Furthermore, this study included nurses from multiple institutions and governorates, representing a diverse range of professional experiences.

The primary objectives of this study were as follows: (1) assess the knowledge gained by nurses after attending EBP/Journal Club (JC) workshops; (2) evaluate changes in knowledge and attitude before and after the workshops; (3) explore differences based on years of nursing experience; and (4) investigate participants’ satisfaction and perceptions regarding the workshops.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A quasi-experimental pre- and post-test study design was employed to explore changes in knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based practice (EBP) and journal club (JC) sessions among nurses who attended the EBP/JC workshop at a tertiary hospital.

2.2. Study Population

The study sample comprised nurses who voluntarily chose to attend the EBP and JC workshop. Participation was open to nurses from various categories, including bedside nurses, ward nurses, and those working in specialized clinics. Furthermore, nurses from multiple institutions were eligible to participate.

2.3. Sampling and Sample Size

To achieve the study objectives, a combination of purposive and convenience sampling methods was employed to select participants based on a specific criterion: attendance at the workshops. This mixed sampling approach facilitated the collection of broader insights and richer information. A total of 30 nurses from various institutions attended the workshop.

2.4. Study Tool and Pilot Testing

The data collection tool was developed based on previous research findings and structured to align with the study’s aims and objectives. Content and face validity were established through consultation with research experts, who evaluated the tool for relevance and clarity. The questionnaire items were extracted from prior literature, organized into a structured format, and reviewed by experts using a point-based rating scale. Subsequently, the tool was pilot-tested to assess its validity and reliability.

The first section of the questionnaire captured the demographic characteristics of the nurse participants, including age, gender, marital status, level of education, current professional role, ward/unit of employment, and years of nursing experience. The second section comprised 12 items assessing participants’ knowledge and attitudes toward evidence-based practice (EBP), focusing on areas such as access to literature, reading habits, collaborative exploration of clinical practice, and perceptions of journal clubs.

The knowledge-related questions used a three-point scale (1 = true, 2 = false, 3 = don’t know), while participants’ attitudes were measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). In addition, five additional items assessing staff nurses’ satisfaction were included in the post-test questionnaire.

The pilot test was conducted with five nurses (n = 5) who had previously participated in journal club activities.

2.5. Data Collection

An online self-administered questionnaire, based on the finalized validated tool, was distributed to all nurses who attended the EBP and Journal Club workshops. Participants were provided with an informed consent form and a study brief outlining the aim, purpose, and objectives of the research. All responses were collected anonymously to ensure participant confidentiality. Data collection was conducted over a two-week period, with a reminder email sent shortly after the initial invitation. Of the 30 nurses listed as workshop participants, 27 agreed to participate in the study. However, only 22 participants completed both the pre- and post-test questionnaires and thus were included in the final paired analysis.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 23. Descriptive statistics were reported as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. Inferential statistics were conducted using paired sample t-tests to evaluate differences between pre- and post-test scores. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of < 0.05 (95% confidence interval). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the 12-item questionnaire were 0.86 (pre-test) and 0.89 (post-test), indicating high internal consistency.

Ethical consideration: This study was approved by the Royal Hospital Scientific Research Board (approval number SRC/26771). Participants were informed about the study’s purpose and provided voluntary consent before participation. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured, and participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ General Characteristics

A total of 22 nurses participated in both the pre-test and post-test surveys assessing the knowledge and attitudes toward the EBP/Journal Club (JC) workshop. Table 1 presents a summary of the participants’ general characteristics.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were female (86.4%). Most participants (54.5%) were between 31 and 40 years of age. In terms of regional distribution, 45.5% were from the Muscat region, followed by 27.3% from North Sharqiya. Regarding educational attainment, 63.6% of the participants held a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree, while 22.7% held a diploma qualification.

In terms of professional experience, approximately 63.6% of the participants had more than eight years of nursing experience, with 31.8% reporting 8–12 years and another 31.8% reporting 13–25 years of experience. With respect to their current professional roles, 45.5% were employed as general nurses and 31.8% as senior nurses.

These findings indicate that the study sample represented a diverse group in terms of demographic and professional backgrounds.

3.2. Training and Development Activity

Table 2 presents the frequency of training and development activities undertaken by participants over the past six months, as well as the number of training hours completed. The majority of participants (63.6%) reported no involvement in training or development activities during this period. Among the 22 participants, only two had accumulated more than 120 training hours.

Table 2.

Summary of training and development activity.

3.3. Knowledge

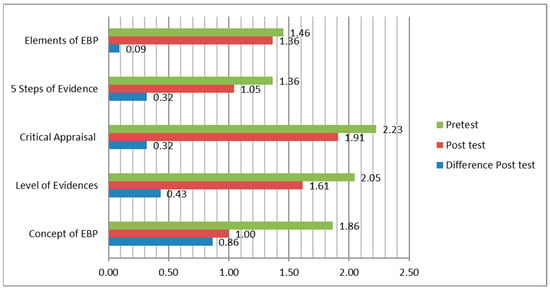

The EBP survey instrument facilitated the quantitative assessment of participants’ knowledge and skills related to evidence-based practice. The results, illustrated in Figure 1, present the mean scores for the knowledge-related survey items.

Figure 1.

Knowledge Factor.

Figure 1 illustrates the differences in participants’ knowledge scores before and after the EBP workshop intervention. Participants demonstrated an improvement in knowledge, with mean scores decreasing from 1.79 ± 0.51 at baseline to 1.24 ± 0.22 following the intervention, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of the before and after comparison of knowledge and attitude (N = 22).

A paired sample t-test was conducted to compare pre- and post-test scores. As shown in Table 3, the mean difference was statistically significant (p = 0.002), indicating that participants’ knowledge improved significantly after attending the EBP workshop.

3.4. Attitude

The mean score for participants’ attitudes toward the usefulness and adoption of EBP increased from the pre-test to the post-test survey. For example, during the post-test survey, most participants strongly agreed with statements such as “engaging in EBP enabled me to perceive its value and feel more confident at work” and “medical professionals should be equipped with EBP knowledge and skills.” However, the paired sample t-test results presented in Table 3 indicate no statistically significant difference between pre-test and post-test attitude scores (p = 0.33).

3.5. Satisfaction

Satisfaction with the EBP workshop was assessed using descriptive statistics, with a summary of results presented in Table 4. Overall, the majority of participants reported positive experiences with the workshop. Among the satisfaction indicators, the highest mean score (4.14) was assigned to the statement recommending that similar workshops should continue in the future. This was followed by the perception that “the EBP workshop was helpful for clinical practices” (mean score = 4.09). Additionally, the participants agreed that they would recommend the workshop to others and found the timing of the sessions to be appropriate, with both indicators receiving a mean score of 4.05.

Table 4.

Satisfaction with EBP.

4. Discussion

The findings of this quasi-experimental study demonstrate that educational workshops focused on research and evidence-based practice (EBP) significantly enhanced nurses’ scientific knowledge, literature retrieval skills, and critical appraisal abilities. Furthermore, participation in the EBP workshops strengthened nurses’ understanding and application of EBP principles in clinical practice.

4.1. Knowledge

As shown in Table 3, participants’ knowledge scores approached 1 (“true”) on the three-point scale (1 = true, 2 = false, 3 = don’t know), indicating a significant improvement from pre- to post-EBP intervention. Similar studies have reported significant enhancements in participants’ knowledge following educational interventions, with overall mean knowledge scores improving post-training [10,11,12,13]. For example, D’Sousa et al. [13] found a statistically significant increase in nurses’ knowledge after participation in EBP-focused educational programs (p < 0.05). Moreover, previous research has demonstrated that nurses who receive EBP education are more likely to apply evidence-based knowledge in clinical practice, positively influencing patient care outcomes [14].

Based on the findings of this study, EBP intervention workshops offer valuable learning opportunities and effectively enhance nurses’ understanding of evidence-based practice concepts. The educational intervention also reinforced nurses’ comprehension of the evidence hierarchy, critical appraisal skills, and the integration of current research into clinical decision making [3]. Supporting these findings, other studies have similarly reported improvements in nurses’ knowledge following attendance at research-focused educational sessions [1,3,15]. A systematic review of 15 studies confirmed that educational interventions significantly enhanced nurses’ knowledge related to EBP [16].

These findings suggest that training workshops, whether conducted in-person, online, or in a hybrid format, play a critical role in advancing nurses’ EBP knowledge and improving the application of evidence in clinical practice [13]. Educational activities such as journal clubs and EBP sessions were also shown to strengthen the adoption of the best available evidence into nursing practice [3,17].

4.2. Attitude

This study found that nurses’ attitudes toward evidence-based practice (EBP) improved in the post-test compared to the pre-test; however, the difference was not statistically significant. This outcome may be explained by the self-selection of participants, as enrollment in the workshop was voluntary. It is likely that nurses who registered already held positive attitudes toward EBP and were motivated to enhance their knowledge. These findings are consistent with a systematic review that reported either no change or only minimal improvement in attitudes following EBP educational interventions [16].

Similarly, Li et al. [18] observed that psychiatric nurses demonstrated only moderate levels of EBP-related behavior (mean behavior score = 4.11 ± 1.36), paralleling the current study’s findings. Although some studies suggest that behavior may improve if leadership actively promotes and reinforces EBP practices within clinical settings [14], other research has shown that structured educational programs can lead to significant positive changes in both behavior and beliefs toward EBP [9,14,19,20,21].

Despite the lack of a statistically significant change in attitudes, the participants in this study expressed a strong willingness to recommend the EBP workshop to others and indicated their intent to continue attending future sessions. As Li et al. [18] emphasized, “it is imperative to engage in conscious behavior and to strengthen advanced education to enhance nurses’ research knowledge.” According to the knowledge–attitude–behavior theory, knowledge directly influences attitude, which in turn indirectly affects behavior. Furthermore, leadership engagement is recognized as a critical factor in fostering a culture of EBP adoption, promoting staff involvement, and encouraging positive behavioral change toward evidence-based practice [15,22,23].

4.3. Satisfaction

This study highlighted the important role of structured educational EBP programs in enhancing participants’ satisfaction. Satisfied participants are more likely to recommend such activities to others, as reflected in the findings of this study, where nurses expressed their intention to continue attending EBP workshops in the future. These results align with previous research demonstrating high levels of satisfaction among nurses who participated in journal club sessions and EBP-related educational activities [24,25].

Nurses tend to report greater satisfaction when educational interventions meet their expectations and are tailored to their professional needs [16,25,26]. Consequently, participants often recommend similar workshops to their colleagues, thereby promoting wider engagement with EBP initiatives [13].

4.4. Strengths and Limitation

This study has several notable strengths. The use of a quasi-experimental pre-and post-test design allowed for the direct measurement of changes in knowledge and attitudes following the intervention. The inclusion of participants from multiple institutions and with varied professional experience enhanced the diversity of the sample. Furthermore, the structured and evidence-based nature of the EBP workshop contributed to the study’s educational rigor.

Nevertheless, several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size and the limited representativeness of participants’ institutions constrained the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study’s quasi-experimental design restricted the ability to conduct follow-up assessments to evaluate the long-term impact of the workshop on participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and the implementation of journal club activities within their institutions. The sampling technique, which combined purposive and convenience sampling, may have also introduced selection bias, further affecting the representativeness of the sample and limiting the robustness of the parametric tests employed. Moreover, reliance on self-reported data could have introduced reporting bias.

Furthermore, as the study was conducted within a specific healthcare context in Oman, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to different regions or healthcare systems. Additionally, because participation in the EBP workshop was voluntary, it is possible that participants were already more motivated or predisposed toward positive attitudes, potentially introducing intervention-selection bias. Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution, considering these methodological constraints.

4.5. Implications for Practice

This study provides a baseline understanding of how EBP workshops can enhance nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and satisfaction. The structure and delivery of EBP initiatives can be further improved by incorporating additional educational materials aimed at deepening participants’ conceptual understanding and encouraging active engagement. Moreover, maintaining the continuity of such workshops is likely to enhance nurses’ clinical performance and the application of evidence-based practice.

Given the high satisfaction levels reported, it would be valuable to explore the integration of interactive and clinically embedded teaching strategies when designing future EBP sessions and workshops. Although this study did not directly assess patient-related outcomes, acknowledging patients as collaborative partners in EBP processes remains critical. Therefore, future research should consider longitudinal designs and larger-scale pre- and post-test studies to assess the long-term effectiveness of EBP educational interventions and to identify factors that contribute to successful EBP adoption. Additionally, greater emphasis on integrating EBP into the development of clinical policies and procedures is recommended to ensure that nursing practice remains grounded in the best available evidence.

5. Conclusions

This quasi-experimental study involving 22 nurses from different regions highlights the critical role of educational workshops focused on research and evidence-based practice (EBP) in enhancing nurses’ scientific knowledge, literature retrieval skills, and critical appraisal abilities. Participation in the EBP workshop also contributed to increased confidence and engagement with EBP principles.

Although participants identified the organization of the workshops as an area needing improvement, overall satisfaction was high. Nurses reported that the workshops positively impacted their clinical practice, expressed intentions to attend future sessions, and indicated a willingness to recommend similar workshops to their colleagues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.; methodology, J.A.M.; validation, W.A.A.; formal analysis, M.A.A.; data curation, J.A.M.; writing—original draft, J.A.M.; writing—review and editing, W.A.A. and M.A.A.; Supervision, M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Royal Hospital Scientific Research Board (approval number SRC#26771; Date of approval: 14 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

The participants of this study were informed about the reasons for this study and were given the option to agree for the participation. All participants were ensured that data are coded and anonymized for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The original data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leonard, A.; Power, N.; Mayet, S.; Coetzee, M.; North, N. Engaging Nurses in Research Awareness Using a New Style of Hospital Journal Club—A Descriptive Evaluation. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 108, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häggman-Laitila, A.; Mattila, L.R.; Melender, H.L. A Systematic Review of the Outcomes of Educational Interventions Relevant to Nurses with Simultaneous Strategies for Guideline Implementation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almomani, E.; Alraoush, T.; Sadah, O.; Al Nsour, A.; Kamble, M.; Samuel, J.; Atallah, K.; Zarie, K.; Mustafa, E. Journal Club as a Tool to Facilitate Evidence Based Practice in Critical Care. Qatar Med. J. 2020, 2019, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vortman, R. Meeting the Doctor of Nursing Practice Essentials through a Journal Club Clinical Experience. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2021, 52, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieny, M.P.; Bekedam, H.; Dovlo, D.; Fitzgerald, J.; Habicht, J.; Harrison, G.; Kluge, H.; Lin, V.; Menabde, N.; Mirza, Z.; et al. Strengthening Health Systems for Universal Health Coverage and Sustainable Development. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017, 95, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Strengthening Health Research and Evidence-Based Decision Making. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/activities/strengthening-health-research-and-evidence-based-decision-making (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Purnell, M.; Skinner, V.; Majid, G. A Paediatric Nurses’ Journal Club: Developing the Critical Appraisal Skills to Turn Research into Practice. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 34, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.E. “Keeping You in the Know”: The Effect of an Online Nursing Journal Club on Evidence-Based Knowledge among Rural Registered Nurses. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2019, 37, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busaidi, I.S.; Al Suleimani, S.Z.; Dupo, J.U.; Al Sulaimi, N.K.; Nair, V.G. Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice in Oman: A Multi-Institutional, Cross-Sectional Study. Oman Med. J. 2019, 34, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.; Couto, F.; Cardoso, A.F.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Santos, L.; Rodrigues, R.; Coutinho, V.; Pinto, D.; Ramis, M.A.; Rodrigues, M.A.; et al. The Effectiveness of an Evidence-Based Practice (Ebp) Educational Program on Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Ebp Knowledge and Skills: A Cluster Randomized Control Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koota, E.; Kääriäinen, M.; Melender, H.L. Educational Interventions Promoting Evidence-Based Practice among Emergency Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 41, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, D.; Fischer-Cartlidge, E. Building Evidence-Based Practice Competency through Interactive Workshops. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2020, 34, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuman, C.J.; Powers, K.; Banaszak-Holl, J.; Titler, M.G. Unit Leadership and Climates for Evidence-Based Practice Implementation in Acute Care: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive Study. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.D.; George, A.; Nair, S.; Noronha, J.; Renjith, V. Effectiveness of an Evidence-Based Practice Training Program for Nurse Educators: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Adawi, M. Evidence Based Practice Through a Journal Club; How Can We Promote Nursing Practice? Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/ebn/2024/01/21/evidence-based-practice-through-a-journal-club-how-can-we-promote-nursing-practice/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Portela Dos Santos, O.; Melly, P.; Hilfiker, R.; Giacomino, K.; Perruchoud, E.; Verloo, H.; Pereira, F. Effectiveness of Educational Interventions to Increase Skills in Evidence-Based Practice among Nurses: The EDITcare Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Alomari, A.M.A.; Singh, K.; Kunjavara, J.; Joy, G.V.; Mannethodi, K.; Al Lenjawi, B. The Nurses Perceived Educational Values and Experience of Journal Club Activities—A Cross-Sectional Study in Qatar. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour to Evidence-Based Practice among Psychiatric Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 9, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonck, P.; de Coning, R. A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of a Skills Capacity Workshop in the South African Public Service. Afr. Eval. J. 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseka, P.U.; Mbakaya, B.C. Knowledge, Attitude and Use of Evidence Based Practice (EBP) among Registered Nurse-Midwives Practicing in Central Hospitals in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Baker, N.N.; AbuAlrub, S.; Obeidat, R.F.; Assmairan, K. Evidence-Based Practice Beliefs and Implementations: A Cross-Sectional Study among Undergraduate Nursing Students. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maydick-Youngberg, D.; Gabbe, L.; Simmons, G.; Smith, D.; Quimson, E.; Meyerson, E.; Manley-Cullen, C.; Rosenfeld, P. Assessing Evidence-Based Practice Knowledge: An Innovative Approach by a Nursing Research Council. J. Nurs. Adm. 2021, 51, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakhras, M.; Al-Mousa, D.S.; Al Mohammad, B.; Spuur, K.M. Knowledge, Attitude, Understanding and Implementation of Evidence-Based Practice among Jordanian Radiographers. Radiography 2023, 29, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenke, R.J.; Thomas, R.; Hughes, I.; Mickan, S. The Effectiveness and Feasibility of TREAT (Tailoring Research Evidence and Theory) Journal Clubs in Allied Health: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, W.Y.; Huang, L.C.; Hung, H.C.; Hung, S.C.; Chuang, T.F.; Yeh, L.Y.; Tseng, H.C. Effectiveness of Digital Flipped Learning Evidence-Based Practice on Nurses’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice: A Quasi-Experimental Trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilla, L.; Ylönen, M.; Laaksonen, C.; Paltta, H.; Von Schantz, M.; Soini, T. Journal Club as a Method for Nurses and Nursing Students’ Collaborative Learning: A Descriptive Study. Health Sci. J. 2013, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Oman Medical Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).