Efficacy of Glycyrrhiza glabra in the Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

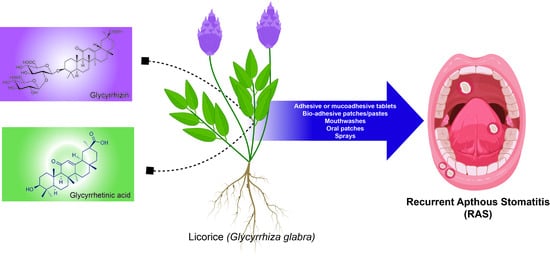

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Protocols

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Type of study: randomized controlled/clinical trial (RCT) and double-blind clinical trial study evaluating the topical treatment of Glycyrrhiza glabra in RAS;

- Type of participant (P): patient with RAS lesion (minor, major, or herpetiform type) diagnosed from the subjective and clinical assessments;

- Type of intervention (I): treatment using Glycyrrhiza glabra in any dosage form, frequency, and duration of treatment;

- Type of comparator (C): control group treated with placebo, antiseptic, or anti-inflammatory agent;

- Type of outcome measure (O): pain intensity measured with a visual analog scale (VAS), the reduction in ulcerated lesion diameter, and the period of RAS healing.

- Non-RCTs, reviews, animal studies, and in vitro studies;

- Patients with underlying diseases, like diabetes mellitus and autoimmune and allergy diseases;

- The clinical diagnosis of RAS is not defined;

- Articles not published in English language.

2.3. Search Strategies

- “licorice” or “Glycyrrhiza glabra”, AND;

- “Recurrent aphthous stomatitis” OR “recurrent aphthous ulceration” OR “RAS” OR “aphthous ulcer” OR “oral ulcer” OR “oral wound” OR “oral lesion”.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.5. Critical Appraisal for Quality if the Study

3. Results

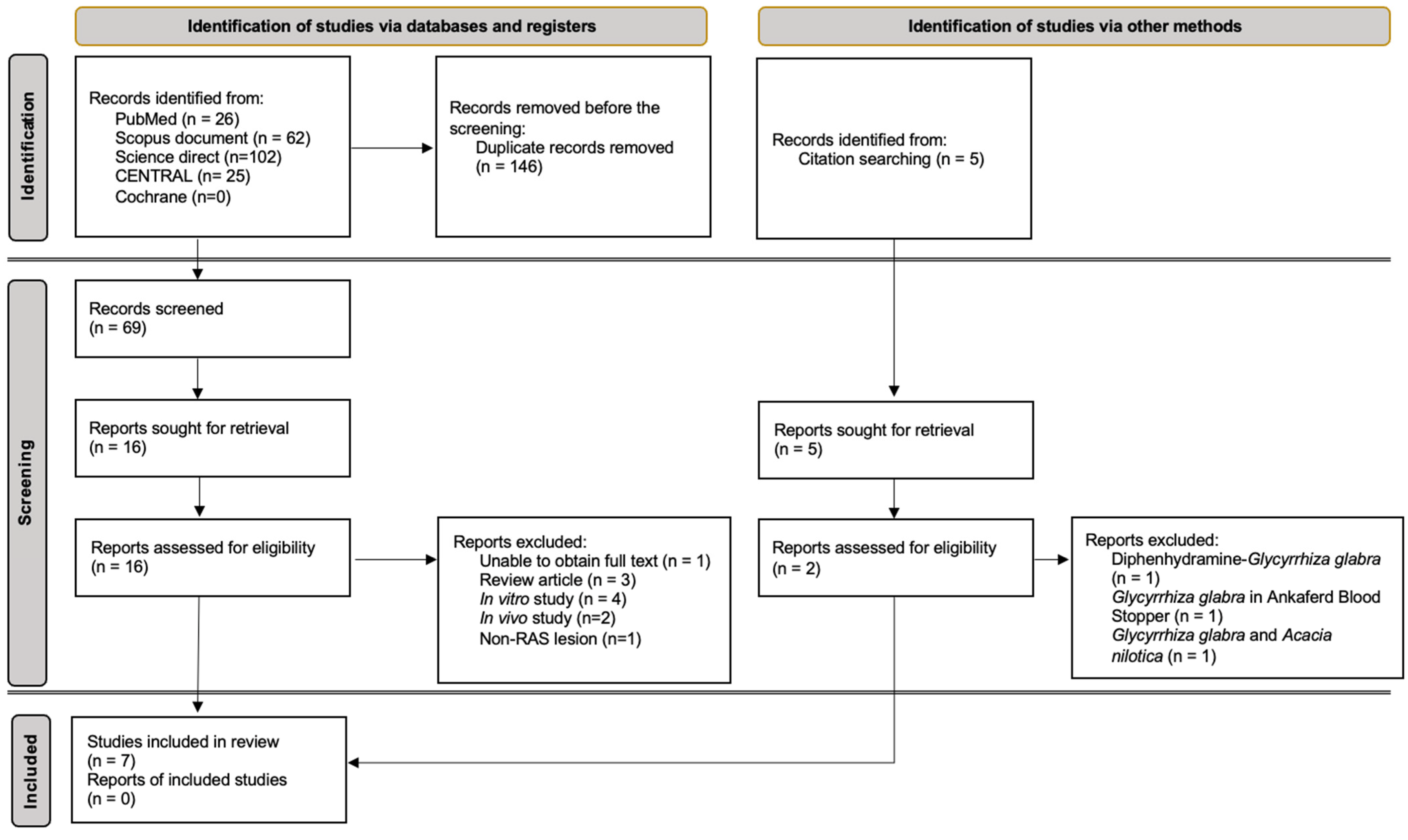

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Study

3.3. Glycyrrhiza glabra Alleviated RAS-Related Pain Intensity

3.4. Glycyrrhiza glabra Accelerating Reduction in RAS Diameter

3.5. Glycyrrhiza glabra Effect on RAS-Related Ulcer Healing Time

3.6. Quality of the Study

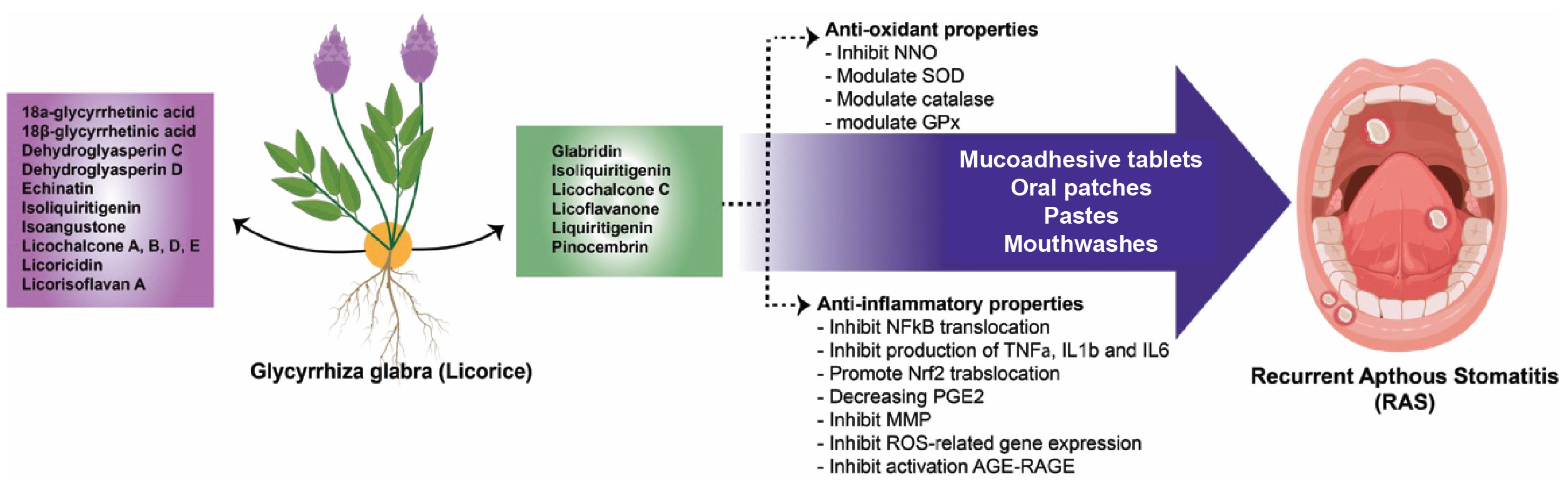

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Archilla, A.; Raissouni, T. Clinical study of 200 patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Gac. Med. Mex. 2023, 154, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, S.; Shahraki, H.R.; Dehkordi, S.D. The association of recurrent aphthous stomatitis with general health and oral health related quality of life among dental students. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2022, 14, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Novrinda, H.; Azhara, C.S.; Rahardjo, A.; Ramadhani, A.; Dong-Hun, H. Determinants and inequality of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in an Indonesian population: A cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, M.A.; Jain, A.; Madtha, S.A.; Cherian, T.M. Prevalence and risk factors of recurrent aphthous stomatitis among college students at Mangalore, India. PeerJ 2023, 11, e14998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.M.; Kumar Vadivel, J.; Ramalingam, K. Prevalence of Aphthous Stomatitis: A Cross-Sectional Epidemiological Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e49288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.L.; Fatahzadeh, M.; A Schwartz, R. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis. Indian J. Dermatol. 2022, 67, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regezi, J.A.; Sciubba, J.J.; Jordan, R.C.K. Oral Pathology: Clinical Pathologic Correlations, 7th ed.; Falk, K., Ed.; Elsevier, Inc.: Maryland Heights, MI, USA, 2017; 402p. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, M. Burket’s Oral Medicine, 12th ed.; Mehta, L.H., McKeon, M., Eds.; People’s Medical Publishing House: Shelton, CT, USA, 2015; 716p. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.B.; Smith, G.P. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A comprehensive review and recommendations on therapeutic options. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unur, M.; Ofluoglu, D.; Koray, M.; Mumcu, G.; Onal, A.; Tanyeri, H. Comparison of a New Medicinal Plant Extract and Triamcinolone Acetonide in Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis. Balk. J. Dent. Med. 2014, 18, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasry, S.; El Shenawy, H.; Mostafa, D.; Ammar, N. Different modalities for treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A Randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2016, 8, e517–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, N.; Asadimehr, N.; Kiani, Z. The effects of licorice containing diphenhydramine solution on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer-Guallar, I.; Jiménez-Soriano, Y.; Claramunt-Lozano, A. Treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A literature review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2014, 6, e168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, P.; Worthington, H.V.; Parnell, C.; Harding, M.; Lamont, T.; Cheung, A.; Whelton, H.; Riley, P. Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2021, CD008676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhina, S.; Singh, A.; Menon, I.; Singh, R.; Sharma, A.; Aggarwal, V. A randomized clinical study for comparative evaluation of Aloe Vera and 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash efficacy on de-novo plaque formation. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, C. Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine: The Basis of Diagnosis and Treatment, 3rd ed.; Taylor, A., Watt, L., Talbott, L., Hitchen, M., Rose, J., Dartmouth Inc./Antbits Ltd., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; 435p. [Google Scholar]

- Katzung, B.G.; Trevor, A.J. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 2337p. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, S.; Annadurai, S.; Abullais, S.S.; Das, G.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, M.F.; Kandasamy, G.; Vasudevan, R.; Ali, M.S.; Amir, M. Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice): A Comprehensive Review on Its Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, Clinical Evidence and Toxicology. Plants 2021, 10, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, P.; Shankargouda, S.; Rath, A.; Ramamurthy, P.H.; Fernandes, B.; Singh, A.K. Therapeutic benefits of liquorice in dentistry. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020, 11, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; El-Mleeh, A.; MAbdel-Daim, M.; Prasad Devkota, H. Traditional Uses, Bioactive Chemical Constituents, and Pharmacological and Toxicological Activities of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (Fabaceae). Biomolecules 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Oxidative stress and cancer: Antioxidative role of Ayurvedic plants. In Cancer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, C.; Epifano, F.; Genovese, S.; Grenier, D. Licorice and its potential beneficial effects in common oro-dental diseases. Oral Dis. 2011, 18, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadamnia, A.A.; Motallebnejad, M.; Khanian, M. The efficacy of the bioadhesive patches containing licorice extract in the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Phytother. Res. 2008, 23, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, D.M.; Ammar, N.M.; El-Anssary, A.A. New Formulations from Acacia nilotica L. and Glycyrrhiza glabra L. Oral Ulcer Remedy. Med. J. Islam. World Acad. Sci. 2013, 21, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, M.; Nasry, S.A.; Mostafa, D.M.; Ammar, N.M. Therapeutic efficacy of herbal formulations for recurrent aphthous ulcer. correlation with salivary epidermal growth factor. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 1097–8135. [Google Scholar]

- Raeesi, V.; Arbabi-Kalati, F.; Akbari, N.; Hamishekar, H. Comparison effectiveness of the bioadhesive paste containing licorice 5% with bioadhesive paste without drug in the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2015, 31, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.-L.; Hsu, P.-Y.; Chung, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Lin, K.-Y. Effective licorice gargle juice for aphthous ulcer pain relief: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 35, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, M.; Saeedi, M.; Ehsani, H.; Sharifian, A.; Moosazadeh, M.; Rostamkalaei, S.; Hatkehlouei, B.M.; Molania, T. Analyzing Glycyrrhiza glabra (Licorice) Extract Efficacy in Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis Recovery. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2018, 6, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.D.; Sherman, J.; van der Ven, P.; Burgess, J. A controlled trial of a dissolving oral patch concerning glycyrrhiza (licorice) herbal extract for the treatment of aphthous ulcers. Gen. Dent. 2008, 56, 206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Bernal, J.; Conejero, C.; Conejero, R. Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020, 111, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surboyo, M.D.C.; Boedi, R.M.; Hariyani, N.; Santosh, A.B.R.; Manuaba, I.B.P.P.; Cecilia, P.H.; Ambarawati, I.G.A.D.; Parmadiati, A.E.; Ernawati, D.S. The expression of TNF-α in recurrent aphthous stomatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine 2022, 157, 155946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślebioda, Z.; Krawiecka, E.; Rozmiarek, M.; Szponar, E.; Kowalska, A.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B. Clinical phenotype of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and interleukin-1β genotype in a Polish cohort of patients. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 46, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Ye, W.; Gong, L.; Lv, K.; Gao, B.; Yao, H. Serum interleukin-6, interleukin-17A, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, F.; Kars, A.; Topal, K.; Yavuz, Z. Systemic immune inflammation index in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 88, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estornut, C.; Rinaldi, G.; Carceller, M.C.; Estornut, S.; Pérez-Leal, M. Systemic and local effect of oxidative stress on recurrent aphthous stomatitis: Systematic review. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 102, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur’Aeny, N.; Gurnida, D.A.; Suwarsa, O.; Sufiawati, I. Serum Level of IL-6, Reactive Oxygen Species and Cortisol in Patients with Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis related Imbalance Nutrition Intake and Atopy. J. Math. Fundam. Sci. 2020, 52, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Y.; Chen, G.; Wu, Z.; Fang, H. Serum levels of total antioxidant status, nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthase in minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis patients. Medicine 2019, 98, e14039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.K. Glycyrrhiza glabra. Edible Med. Non-Med. Plants 2005, 10, 354. [Google Scholar]

- Badkhane, Y.; Yadav, A.S.; Bajaj, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Raghuwanshi, D.K. Glycyrrhiza glabra L.: A Miracle Medicinal Herb. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, Z.; Mirzaei, H.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Sadeghi Mahoonak, A.R.; Khomeiri, M. Effect of harvest time on antioxidant activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra root extract and evaluation of its antibacterial activity. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 2951–2957. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Belén, L.H.; Kaur, R.; Kregiel, D.; Uprety, Y.; Beyatli, A.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Kırkın, C.; et al. Glycyrrhiza Genus: Enlightening Phytochemical Components for Pharmacological and Health-Promoting Abilities. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 7571132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Yuan, B.-C.; Ma, Y.-S.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y. The anti-inflammatory activity of licorice, a widely used Chinese herb. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 55, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacique, A.P.; Barbosa, É.S.; de Pinho, G.P.; Silvério, F.O. Maceration extraction conditions for determining the phenolic compounds and the antioxidant activity of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. Cienc. Agrotecnologia 2020, 44, e017420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, N.M.P.; Warditiani, N.K.; Laksmiani, N.P.L.; Widjaja, I.N.K.; Rismayanti, A.A.M.I.; Wirasuta, I.M.A.G. Perbandingan Metode Ekstraksi Maserasi dan Refluks Terhadap Rendemen Andrografolid dari Herba Sambiloto (Andrographis paniculata (Burm.f.) Nees). Univ. Udayana 2014, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, A.R.; Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: Basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Singh, A.; Kumari, P.; Nishad, J.H.; Gautam, V.S.; Yadav, M.; Bharti, R.; Kumar, D.; Kharwar, R.N. Advances in extraction technologies: Isolation and purification of bioactive compounds from biological materials. In Natural Bioactive Compounds; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.-J.; Son, D.-H.; Chung, T.-H.; Lee, Y.-J. A Review of the Pharmacological Efficacy and Safety of Licorice Root from Corroborative Clinical Trial Findings. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frattaruolo, L.; Carullo, G.; Brindisi, M.; Mazzotta, S.; Bellissimo, L.; Rago, V.; Curcio, R.; Dolce, V.; Aiello, F.; Cappello, A.R. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Flavanones from Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (licorice) Leaf Phytocomplexes: Identification of Licoflavanone as a Modulator of NF-kB/MAPK Pathway. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschelli, S.; Pesce, M.; Vinciguerra, I.; Ferrone, A.; Riccioni, G.; Antonia, P.; Grilli, A.; Felaco, M.; Speranza, L. Licocalchone-C Extracted from Glycyrrhiza glabra Inhibits Lipopolysaccharide-Interferon-γ Inflammation by Improving Antioxidant Conditions and Regulating Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression. Molecules 2011, 16, 5720–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiyagarajan, P.; Chandrasekaran, C.V.; Deepak, H.B.; Agarwal, A. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory mediators by an extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra and its phytoconstituents. Inflammopharmacology 2011, 19, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siracusa, L.; Saija, A.; Cristani, M.; Cimino, F.; D’Arrigo, M.; Trombetta, D.; Rao, F.; Ruberto, G. Phytocomplexes from liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) leaves—Chemical characterization and evaluation of their antioxidant, anti-genotoxic and anti-inflammatory activity. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S.; Geng, X.; Jiang, H.; Dai, Y.; Wang, P.; Hua, M.; Gao, Q.; Lang, S.; Hou, L.; et al. Antioxidant Effects of Roasted Licorice in a Zebrafish Model and Its Mechanisms. Molecules 2022, 27, 7743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, J.; Tian, S.; Liu, Y. The anti-diabetic activity of licorice, a widely used Chinese herb. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.; Atiq, A.; Ain, Q.U.; Ali, J.; Khan, S.; Ali, H. Evaluating the mucoprotective effects of glycyrrhizic acid-loaded polymeric nanoparticles in a murine model of 5-fluorouracil-induced intestinal mucositis via suppression of inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1539–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surboyo, M.D.C.; Mansur, D.; Kuntari, W.L.; Syahnia, S.J.M.R.; Iskandar, B.; Arundina, I.; Liu, T.-W.; Lee, C.-K.; Ernawati, D.S. The hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-sorbitol thin film containing a coconut shell of liquid smoke for treating oral ulcer. JCIS Open 2024, 15, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, S.; Xu, H.; Guo, J.; Yan, F. Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and wet-adhesive poly(ionic liquid)-based oral patch for the treatment of oral ulcers with bacterial infection. Acta Biomater. 2023, 166, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Mei, L.; Wang, D.; Jia, P.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, W. A self-stabilized and water-responsive deliverable coenzyme-based polymer binary elastomer adhesive patch for treating oral ulcer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Study | Type of RAS | Control Group | Intervention Group | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject (n) | Dosage From | Subject (n) | Dosage Form | Frequency of Treatment | |||

| Placebo-controlled, observer-blind, consecutive-group clinical trial | Minor | - | Vehicle patch | 15 | Patch | Once daily | [23] |

| Randomized controlled trial | Minor | 7 | No treatment | 7 | Paste | Three times daily | [24] |

| Randomized controlled trial | NS | 10 | No treatment | 10 | Paste | Four times daily | [25] |

| Randomized controlled double-blind | Minor | 20 | Placebo patch | 20 | Paste | Four times daily | [26] |

| 20 | Diphenhydramine mouthwash | ||||||

| Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Minor Major Herpetiform | 24 | Xylitol mouthwash | 30 | Mouthwash | Four times daily | [27] |

| Double-blind clinical trial | Minor | 21 | Placebo mucoadhesive tablet | 21 | Mucoadhesive tablet | Three times daily | [28] |

| Double-blind clinical trial | NR | 23 | Placebo patch | 23 | Patch | Once daily | [29] |

| 23 | No treatment | ||||||

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | Processing Technique | Dosage Form | Concentration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | Maceration | Patch | 1% | [23] |

| Roots and rhizomes | Maceration | Paste | Whole extract | [24] |

| Roots | Maceration | Paste | 1% | [25] |

| Roots and rhizomes | Maceration | Paste | 5% | [26] |

| NR | NR | Mouthwash | NR | [27] |

| Roots | Maceration | Mucoadhesive tablet | 17.25% | [28] |

| Roots | NR | Patch | NR | [29] |

| Dosage form of Glycyrrhiza glabra | Control | Duration of Treatment | Pain Assessment | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch | Vehicle patch | Once daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 1 and 5 days | [23] |

| Paste | No treatment | Four times daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 2 and 5 days | [25] |

| Paste | Placebo paste | Four times daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 3 and 5 days | [26] |

| Mouthwash | Xylitol mouthwash | Four times daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 1 and 2 days | [27] |

| Mucoadhesive tablet | Diphenhydramine mouthwash | Three times daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 1 until 7 days | [28] |

| Placebo mucoadhesive tablet | |||||

| Patch | Placebo or patch | Once daily | VAS | Significant pain reduction after 1 day | [29] |

| No treatment |

| Dosage form of Glycyrrhiza glabra | Control | Duration of Treatment | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch | Vehicle patch | Once daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 5 days | [23] |

| Paste | No treatment | Three times daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 2 and 3 days | [24] |

| Paste | No treatment | Four times daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 2 and 5 days | [25] |

| Paste | Placebo paste | Four times daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 3 and 5 days | [26] |

| Diphenhydramine mouthwash | ||||

| Mouthwash | Xylitol mouthwash | Four times daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 1 and 2 days | [27] |

| Mucoadhesive tablet | Placebo mucoadhesive tablet | Three times daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 3, 5, and 7 days | [28] |

| Patch | Placebo or no treatment | Once daily | Significant ulcer diameter reduction after 8 days | [29] |

| Dosage form of Glycyrrhiza glabra | Control | Duration of Treatment | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch | Vehicle patch | Once a day | No significant healing time | [23] |

| Paste | Placebo paste | Four times daily | Significantly faster ulcer healing | [26] |

| Diphenhydramine mouthwash | ||||

| Mouthwash | Diphenhydramine mouthwash | Four times daily | Significantly faster ulcer healing after 1, 3, and 7 days | [29] |

| Assessment Criteria | [23] | [24] | [26] | [28] | [29] | [27] | [25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection criteria | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Randomization | x | X | √ | o | o | o | o |

| Blinding | o | X | √ | o | x | √ | X |

| Follow-up rate | X | X | X | X | X | √ | X |

| Intervention detail | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Outcome measure | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Statistical analysis | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Quality | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | High | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Oman Medical Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iskandar, A.S.; Nisa, G.S.N.; Queen, H.; Wicaksono, S.; Surboyo, M.D.C.; Ernawati, D.S. Efficacy of Glycyrrhiza glabra in the Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Oman Med. Assoc. 2025, 2, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/joma2010008

Iskandar AS, Nisa GSN, Queen H, Wicaksono S, Surboyo MDC, Ernawati DS. Efficacy of Glycyrrhiza glabra in the Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the Oman Medical Association. 2025; 2(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/joma2010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleIskandar, Annisa Sabrina, Ghinaya Shaliha Nursaida Nisa, Hanifa Queen, Satutya Wicaksono, Meircurius Dwi Condro Surboyo, and Diah Savitri Ernawati. 2025. "Efficacy of Glycyrrhiza glabra in the Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials" Journal of the Oman Medical Association 2, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/joma2010008

APA StyleIskandar, A. S., Nisa, G. S. N., Queen, H., Wicaksono, S., Surboyo, M. D. C., & Ernawati, D. S. (2025). Efficacy of Glycyrrhiza glabra in the Treatment of Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of the Oman Medical Association, 2(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/joma2010008