Edible Oils from Health to Sustainability: Influence of the Production Processes in the Quality, Consumption Benefits and Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Study type: Randomized controlled trials (parallel or crossover), prospective cohort studies, or experimental studies in animal models.

- Participants: Humans (adults ≥ 18 years), healthy or with clinical conditions, and animal models (mainly rodents). Studies involving pregnant or lactating women and individuals under 18 years were excluded.

- Intervention: Oral administration of vegetable oils in any form or dosage, with clear specification of oil type and processing method (e.g., pressing, refining).

- Vegetable oil production: Studies reporting on raw material and quality control.

- Outcomes: At least one of the following: body weight control, hepatoprotective effects, gut microbiota modulation, reduction in cardiovascular risk factors, or outcomes related to diabetes mellitus and cancer

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessments

- ROB2 domains: bias due to randomization, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting.

- ROBINS-I domains: bias due to confounding, participant selection, intervention/exposure classification, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting.

- SYRCLE domains: selection bias (randomization and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of caretakers/researchers), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors), attrition bias, and selective reporting.

3. Results

3.1. Human Studies

3.2. Animal Studies

3.3. Vegetable Oil Production: Raw Material and Quality Control

3.3.1. Quality Control of Vegetable Oils Raw Material Production

3.3.2. Influence of Postharvest Handling and Processing of Raw Materials on Vegetable Oil Quality

3.3.3. Technological Application of Vegetable Oils and Its Benefits

3.3.4. Other Quality Concerns

3.4. Contamination by PAHs and Heavy Metals

| Author | Country | Oil(s) | * Contaminants | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohajer et al. [8] | Iran | Rice bran oil. | Pb, As, Cd, Zn, Cu, Mn. | Levels near U.S. EPA thresholds; potential health risk. |

| Antoniadis et al. [42] | Greece | Olives (from contaminated soil). | Ag, As, Cd, Pb, Sb, Tl, Zn. | Cd > EU limit (0.05 mg/kg); health risks confirmed for As and Pb. |

| Souza et al. [40] | Brazil | Olive oil, soybean oil, margarine. | Cd, Cu, Cr, Fe, Mn, Ni, V, Zn. | Environmental contamination influenced levels; monitoring recommended. |

| Tayeb & Movassaghghazani [43] | Iran | Olive and corn oils. | Cd, Pb. | Traditional olive oil presented potential risk (Pb). |

| He et al. [6] | China | Camellia, peanut, flaxseed, corn germ, sesame. | PAHs. | Levels 6–9 μg/kg (all > EU limit of 2 μg/kg); rapeseed, sunflower, olive, soybean < 6 μg/kg but still above limit. |

| Bechar et al. [7] | Morocco | Extra virgin olive oil. | Cd, Pb, Cr, Ni, Zn, As, Cu. | Levels within legal limits, but regional variation observed. |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Oil | PAHs (µg/kg) | Contaminants (µg/kg) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Camellia | 7.15 | NA | [6] |

| Sunflower | 5.63 | As 0.55; Ni 1.20; Zn 69.60; Cu 3.23; Pb 0.67; Mn 2.29; V 0.15 | [6,48] |

| Olive | 5.39 | As 7.65–9.06; Cr 7.12–9.43; Cd 3.14–5.06; Ni 6.14–8.38; Zn 18.15–28.55; Cu 16.52–21.90; Pb 3.14–17.48; Fe 56.12; Mn 6.12 | [6,7,43,48] |

| Soybean | 5.34 | As 1.58; Pb 1.12; Ni 0.96; Zn 111.09; Cu 4.44; Mn 1.96 | [6,48] |

| Peanut | 6.44 | As 5–89 *; Cd 6–9 *; Fe 5655–11,323 *; Pb 25–27 *; Zn 2863–8835 * | [6,49] |

| Flaxseed | 8.62 | Pb 25.65; Cd 70.03; As 3.10; Al 29,814 * | [6,50] |

| Corn | 6.08–182.79 | Pb 19.27–32.40; Cd 4.48–5.77 | [6,43,51] |

| Sesame | 6.31 | As 64–91 *; Cd 9 *; Fe 15,091–23,664 *; Pb 9–13 *; Zn 3192–6299 * | [6,49] |

| Rice Bran | NA | As 2.46; Cd 0.07; Ni 0.97; Zn 101.36; Cu 21.08; Pb 2.57; Mn 2.44 | [48] |

| Palm | 22.6 | As 2.8; Ni 10.08; V 0.55; Cr 5.36; Co 0.21; Cu 17.94; Zn 191.04; Pb 2.01; Mn 26.31 | [48,51] |

| Canola | 129.28 | As 0.67; Ni 0.27; Cu 9.82; Zn 65.36; Pb 1.03; Mn 0.89 | [48,52] |

| Rapeseed | 4.35 | Cd 1–7 *; Pb 12–100 *; As 1–10 *; Hg < 5–10 *; Cu 36–55 *; Fe 236–1320 * | [6,52] |

References

- Martín-Torres, S.; Ruiz-Castro, L.; Jiménez-Carvelo, A.M.; Cuadros-Rodríguez, L. Applications of multivariate data analysis in shelf life studies of edible vegetal oils—A review of the few past years. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijaard, E.; Virah-Sawmy, M.; Newing, H.S.; Ingram, V.; Holle, M.J.; Pasmans, T.; Omar, S.; Van den Hombergh, H.; Unus, N.; Fosch, A.; et al. Exploring the Future of Vegetable Oils: Oil Crop Implications—Fats, Forests, Forecasts, and Futures. IUCN; Sustainable Nutrition Scientific Board (SNSB): Gland, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella-Martínez, C.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Vera CNRd Fernández-López, J.; Viuda-Martos, M. Healthier Oils: A New Scope in the Development of Functional Meat and Dairy Products: A Review. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Aldhalmi, A.K.; Attia, A.I.; Ibrahem, Z.A.; Alshehry, G.; Loutfi, M.; Elolimy, A.A.; El-Kholy, M.S. Effects of including different levels of equal mix of soybean and flaxseed oils in Japanese quail diets on the growth, carcass quality, and blood biomarkers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.L.; He, H.; Jin, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhang, L.; Xue, M.; Fan, J.; Wang, S. Occurrence of EU-priority polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in edible oils and associated with human health risks in Hangzhou city of China. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 145, 107834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechar, S.; Najimi, C.; Mohamed, K.; Essediya, C.; Nounah, A. Geographical distribution of potentially toxic elements in olive oils from the Fes-Meknes region of Morocco and their health risk assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 203, 115608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajer, A.; Baghani, A.N.; Sadighara, P.; Ghanati, K.; Nazmara, S. Determination and health risk assessment of heavy metals in imported rice bran oil in Iran. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 86, 103384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarilla, L.D.; Grilli, G.; Huais, P.Y.; Labuckas, D.; Maestri, D.; Ferrarese, M.; Tourn, E.; Szawarski, N.; Grandinetti, G.; Ferreira, M.F.; et al. Pollinators significantly enhance seed set, yields and chemical parameters of oil seed in sunflower crops. Field Crops Res. 2025, 322, 109736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, P.; Wu, F.; He, W.; Mao, L.; Jia, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiao, J. Cooking oil/fat consumption and deaths from cardiometabolic diseases and other causes: Prospective analysis of 521,120 individuals. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voon, P.T.; Ng, C.M.; Ng, Y.T.; Wong, Y.J.; Yap, S.Y.; Leong, S.L.; Yong, X.S.; Lee, S.W. Health Effects of Various Edible Vegetable Oils: An Umbrella Review. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Morvaridzadeh, M.; Pizarro, A.B.; Rouzitalab, T.; Khorshidi, M.; Izadi, A.; Shidfar, F.; Omidi, A.; Heshmati, J. Effect of extra virgin olive oil consumption on glycemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1953–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernáez, Á.; Fernández-Castillejo, S.; Farràs, M.; Catalán, Ú.; Subirana, I.; Montes, R.; Solà, R.; Muñoz-Aguayo, D.; Gelabert-Gorgues, A.; Díaz-Gil, Ó.; et al. Olive Oil Polyphenols Enhance High-Density Lipoprotein Function in Humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karupaiah, T.; Chuah, K.A.; Chinna, K.; Matsuoka, R.; Masuda, Y.; Sundram, K.; Sugano, M. Comparing effects of soybean oil- and palm olein-based mayonnaise consumption on the plasma lipid and lipoprotein profiles in human subjects: A double-blind randomized controlled trial with cross-over design. Lipids Health Dis. 2016, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njike, V.Y.; Ayettey, R.; Treu, J.A.; Doughty, K.N.; Katz, D.L. Post-prandial effects of high-polyphenolic extra virgin olive oil on endothelial function in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled crossover trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 330, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.J.; Henderson, T.; Gebauer, S.K. Consumption of High-Oleic Soybean Oil Improves Lipid and Lipoprotein Profile in Humans Compared to a Palm Oil Blend: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Lipids 2021, 56, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Li, Y.; Willett, W.C.; Sun, Q.; Sampson, L.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F.B. Consumption of Olive Oil and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality Among U.S. Adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, R.; Kapravelou, G.; Cubedo, M.; Solanas, M.; Escrich, E. Body weight gain and control: Beneficial effect of extra virgin olive oil versus corn oil in an experimental model of mammary cancer. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 125, 109549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tao, H.; Shentu, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xu, T. Camellia seed oil exerts a more gradual influence on the progression of high-fat diet induced NAFLD mice compared to corn oil: Insights from gut microbiota and metabolomics. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Pacheco, L.S.; Tessier, A.J.; Li, Y.; Willett, W.C.; Sun, Q.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F.B. Changes in olive oil consumption and long-term body weight changes in 3 United States prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 121, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesteiro, E.; Galera-Gordo, J.; González-Gross, M. Aceite de palma y salud cardiovascular: Consideraciones para valorar la literatura. Nutr. Hosp. 2018, 35, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, M.B.; Costa, J.; Zucchetti, J.I.; Pavlovic, T.; Calace, P.; Saigo, M.; Wheeler, M.C. Protein characterization of the soybean malic enzyme family to select metabolic targets for seed oil improvement. Plant Sci. 2025, 360, 112707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé-Rodríguez, S.; Ledesma-Escobar, C.A.; Miho, H.; Muñoz, C.; Priego-Capote, F. Deciphering the influence of the cultivar on the phenolic content of virgin olive oil. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 129, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiday, L. Red palm oil. International News on Fats, Oils, and Related Materials. INFORM 2017, 28, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.L.; Pai, M.M.; Krishnaprasad, P.R.; Pai, M.V.; Murlimanju, B.V.; Mohan, A.; Prabhu, L.V.; Vadgaonkar, R. Virgin coconut oil—Its methods of extraction, properties and clinical usage: A review. La Clin. Ter. 2024, 175, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablaoui, C.; Besombes, C.; Jamoussi, B.; Rhazi, L.; Allaf, K. Comparison of expander and Instant Controlled Pressure-Drop DIC technologies as thermomechanical pretreatments in enhancing solvent extraction of vegetal soybean oil. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 7235–7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeaiter, A.; Besombes, C.; Rhazi, L.; Haddarah, A.; Hamieh, T.; Allaf, K. How does instant autovaporization deepen the cold press-extraction process of sunflower vegetal oil? J. Food Eng. 2019, 263, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajski, Ł.; Lozano, A.; Uclés, A.; Ferrer, C.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Determination of pesticide residues in high oil vegetal commodities by using various multi-residue methods and clean-ups followed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1304, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, L.D.; López, D.S.; Montealegre, Á.M.; Eim, V.S.; Sandoval-Aldana, A. Study of the physicochemical properties of hass avocado oil encapsulated by complex coacervation. LWT 2024, 204, 116491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamoussi, B.; Jablaoui, C.; Hajri, A.K.; Chakroun, R.; Al-Mur, B.; Allaf, K. Deodorization process of vegetal soybean oil using Thermomechanical Multi-Flash Autovaporization (MFA). LWT 2022, 167, 113823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Belloch, C.; Salvador, A. Sunflower oil oleogels as alternative fat in hybrid meat patties. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Solivelles, S.; Li, L.; Belloch, C.; Flores, M. Effect of partial substitution of animal by vegetal ingredients on the quality of hybrid dry-fermented sausages. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, K.N.; Kuş, B.; Gürkan, R. A new ion-pair ultrasound assisted-cloud point extraction approach for determination of trace V(V) and V(IV) in edible vegetal oils and vinegar by spectrophotometry. Microchem. J. 2019, 150, 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, J.A.N.; Culluzpuma, A.C.; Llaguno, S.N.S.; Montiel, J.A.P.; Garcia, I.P.V. Estudio de las condiciones del proceso de extracción de aceite de Aguacate (Persea americana) con fines alimenticios en Ecuador. Nutr. Clín. Dietética Hosp. 2021, 41, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, S.C.; Kafatos, A. Vegetable Oils: Dietary Importance. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier: Kidlington, UK; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R0915 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- European Union. Official Journal of the European Union. 2021. Available online: https://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/783d5a5d-fa7b-11eb-b520-01aa75ed71a1.0006.03 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Barbosa, F.; Rocha, B.A.; Souza, M.C.O.; Bocato, M.Z.; Azevedo, L.F.; Adeyemi, J.A.; Santana, A.; Campiglia, A.D. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs): Updated aspects of their determination, kinetics in the human body, and toxicity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part B 2023, 1, 28–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.M.D.; Toloza, C.A.T.; Aucélio, R.Q. Fast determination of trace metals in edible oils and fats by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and ultrasonic acidic extraction. J. Trace Elem. Miner. 2022, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Antoniadis, V.; Thalassinos, G.; Levizou, E.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.L.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J. Hazardous enrichment of toxic elements in soils and olives in the urban zone of Lavrio, Greece, a legacy, millennia-old silver/lead mining area and related health risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 434, 128906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayeb, J.; Movassaghghazani, M. Assessment of lead and cadmium exposure through olive and corn oil consumption in Gonbad-Kavus, north of Iran: A public health risk analysis. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 14, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Updates Guidelines on Fats and Carbohydrates. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-07-2023-who-updates-guidelines-on-fats-and-carbohydrates (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Su, R.; Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Ding, W.; Feng, L. Effects of Prenatal Arsenic, Cadmium, and Manganese Exposure on Neurodevelopment in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamas, G.A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Jones, M.R.; Mann, K.K.; Nasir, K.; Tellez-Plaza, M.; Ujueta, F.; Navas-Acien, A.; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; et al. Contaminant Metals as Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e029852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Morata, I.; Schilling, K.; Glabonjat, R.A.; Domingo-Relloso, A.; Mayer, M.; McGraw, K.E.; Galvez Fernandez, M.; Sanchez, T.R.; Nigra, A.E.; Kaufman, J.D.; et al. Association of Urinary Metals With Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and All-Cause Mortality in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 150, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.T.; Liao, K.W.; Xuan, T.C.; Chiou, T.Y.; Lin, Z.E.; Lee, W.J. Determination, distribution, and health risk assessment of 12 heavy metals in various edible oils in Taiwan. JSFA Rep. 2024, 4, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehri, F.; Heshmati, A.; Ghane, E.T.; Khazaei, M.; Mahmudiono, T.; Fakhri, Y. A probabilistic health risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in edible vegetable oils consumed in Hamadan, Iran. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Hwang, J.Y.; Lee, H.E.; Kim, T.H.; Choi, J.D.; Gang, G.J. Effects of food processing methods on migration of heavy metals to food. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2019, 62, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, L.; Veyrand, B.; Adegboye, A.; Hossou, S.E.; Koné, A.Z.; Oyedele, A.D.; Kisito, C.S.; Dembélé, Y.K.; Eyangoh, S.; Verger, P.; et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in foods from the first regional total diet study in Sub-Saharan Africa: Contamination profile and occurrence data. Food Control 2019, 103, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Shemshadi, G.; Khorshidian, N.; Ghasemzadeh-Mohammadi, V.; Fakhri, Y.; Hosseini, H.; Khaneghah, A.M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) content of edible vegetable oils in Iran: A risk assessment study. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Country | Study Type | Population | Duration | Intervention | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

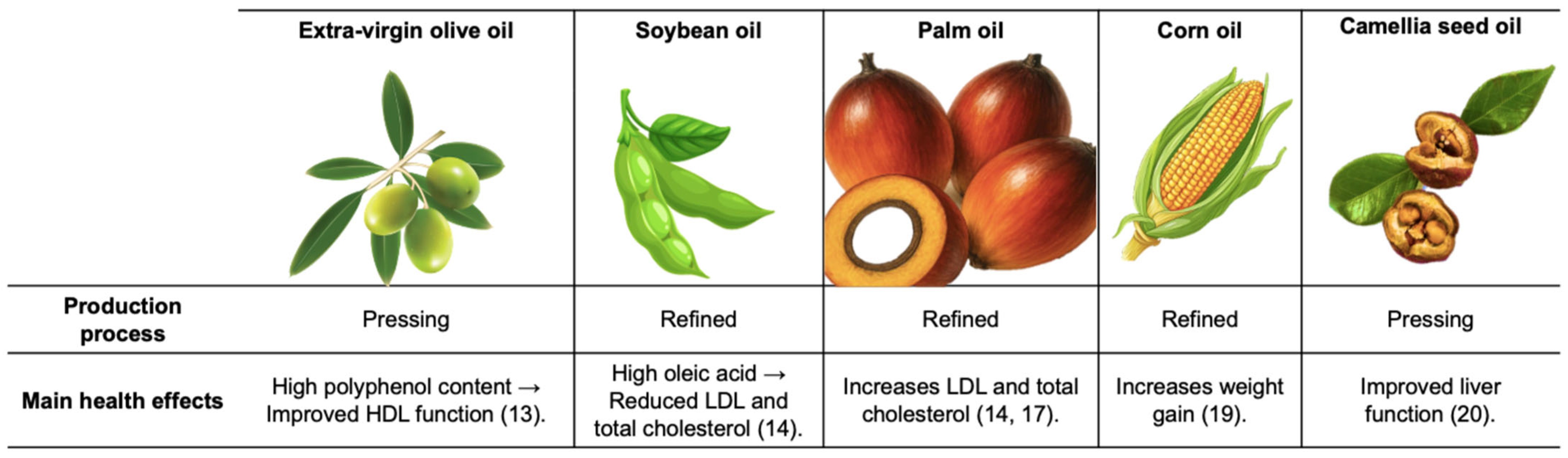

| Hernáez et al. [13] | Spain | Randomized | 47 healthy men. | 3 weeks per intervention (washout 2 weeks) | 25 mL/day extra virgin olive oil with low vs. high polyphenol content. | High-polyphenol olive oil improved HDL function (cholesterol efflux, HDL composition and fluidity). |

| Karupaiah et al. [14] | Malaysia | Randomized | 36 healthy adults. | 4-week periods (washout 2 weeks) | Mayonnaise made with soybean oil vs. palm olein. | Soybean oil mayonnaise reduced total and LDL cholesterol more than palm olein mayonnaise. |

| Estruch et al. [15] | Spain | Randomized | 7447 adults (55–80 years) at high cardiovascular risk. | Median 4.8 years | Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts vs. low-fat control diet. | Reduced incidence of major cardiovascular events; Mediterranean diet with unsaturated fats beneficial. |

| Njike et al. [16] | USA | Randomized, | 20 adults at risk for type 2 diabetes. | – | 50 mL of high-polyphenol extra virgin olive oil. | Improved endothelial function; no blood pressure change. |

| Baer et al. [17] | USA | Randomized | 60 healthy adults. | 4-week periods (crossover) | High-oleic soybean oils vs. compared to other alternative oils. | High-oleic soybean oils improved lipid and lipoprotein profile, lowering total cholesterol and LDL compared to partially hydrogenated oils. |

| Zhang et al. [10] | USA | Prospective Study | 521,120 adults, 50–71 years. | 16 years | Substitution of butter/margarine with vegetable oils, including olive oil. | Vegetable oils linked to lower mortality. |

| Guasch-Ferré et al. [18] | USA | Prospective Study | 92,383 adults. | 28 years | >7 g/day of olive oil. | Reduced total and cause-specific mortality. |

| Moral et al. [19] | Spain | Experimental Study | 818 Rats | 150 to 274 days | Corn oil vs. Olive oil (with extra virgin olive oil + corn oil). | Corn oil increased weight gain. Extra virgin olive oil helped control weight gain. |

| Zhou et al. [20] | China | Experimental Study | 15 Mice | 12 weeks | High-fat diet + oral camellia seed oil compared with corn oil. | Camellia seed oil reduced liver fat, improved liver function and gut microbiota. |

| Author | Raw Material | Nutritional/Functional Benefits | Antinutritional Risks/Contaminants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jamoussi et al. [31]; Badia et al. [23]; Jablaoui et al. [27] | Soy | Polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic, 50–55%), monounsaturated fatty acids (oleic, 20–25%), antioxidant tocopherols; MFA and DIC technologies preserve bioactive compounds. | Trans fats, 3-MCPD, glycidyl esters; accumulation of Cd and Pb in contaminated soils. |

| Daza et al. [30]; Rajski et al. [29]; Neira Mosquera et al. [35] | Avocado | 60–70% oleic acid, carotenoids, phytosterols, and tocopherols; encapsulation and cold pressing preserve stability and bioactive compounds. | Persistent lipophilic pesticides; mycotoxins in poorly stored seeds. |

| Rajski et al. [29] | Almond | Predominance of oleic and linoleic acids; high metabolic and functional value; source of antioxidants. | Persistent lipophilic pesticides; mycotoxins in poorly stored seeds. |

| Gesteiro et al. [22]; Cassiday [25] | Palm (Conventional, RBD) | Oleic C18:1 (35.79) and linoleic C18:2 (14.77) acids | High content of palmitic acid (Saturated fatty acids). Refining, bleaching, and deodorization processes drastically reduce the content of carotenoids, lycopene, xanthophylls, tocopherols, and tocotrienols. |

| Gesteiro et al. [22]; Cassiday [25] | Red Palm (CPO, RPO) | High content of carotenoids, tocopherols and tocotrienols, 70% in the form of tocotrienols. | High content of palmitic acid (Saturated fatty acids). Strong taste, smell like overripe mushrooms. Free fatty acids (FFA), moisture, trace meals, and other impurities. |

| Tomé-Rodríguez et al. [24] | Olive | 55–80% oleic acid; phenolic compounds (oleuropein, oleacein, oleocanthal) with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective activity. | Low risk of lipid oxidation; possible migration of contaminants during extraction if not controlled. |

| Flores et al. [32]; Zeaiter et al. [28]; Amarilla et al. [9] | Sunflower seed | Profile rich in oleic and linoleic acid. Development of oleogels could reduce saturated fatty acids in processed food and improve PUFA/SFA ratio. | Lipidic oxidation by high unsaturation; contaminants related to the refining process. |

| Garcia-Solivelles et al. [33]; Savva & Kafatos [36]; Rao et al. [26] | Coconut | Increase serum HDL cholesterol more than LDL cholesterol to give a more favorable lipid profile relative to dietary carbohydrates. Mimic the properties of animal fats providing solid like texture. | High content of saturated fatty acids. Loss of antioxidants during hot processing, microbial contamination during fermentation, and possible trace metal accumulation (e.g., cadmium, vanadium, lead) if coconuts are grown in contaminated soils. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, V.d.S.; Arias, L.V.A.; Usberti, F.C.S.; Oliveira, R.A.d.; Fakhouri, F.M. Edible Oils from Health to Sustainability: Influence of the Production Processes in the Quality, Consumption Benefits and Risks. Lipidology 2025, 2, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040021

Silva VdS, Arias LVA, Usberti FCS, Oliveira RAd, Fakhouri FM. Edible Oils from Health to Sustainability: Influence of the Production Processes in the Quality, Consumption Benefits and Risks. Lipidology. 2025; 2(4):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040021

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Viviane de Souza, Luna Valentina Angulo Arias, Franciane Colares Souza Usberti, Rafael Augustus de Oliveira, and Farayde Matta Fakhouri. 2025. "Edible Oils from Health to Sustainability: Influence of the Production Processes in the Quality, Consumption Benefits and Risks" Lipidology 2, no. 4: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040021

APA StyleSilva, V. d. S., Arias, L. V. A., Usberti, F. C. S., Oliveira, R. A. d., & Fakhouri, F. M. (2025). Edible Oils from Health to Sustainability: Influence of the Production Processes in the Quality, Consumption Benefits and Risks. Lipidology, 2(4), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/lipidology2040021