The Application of Blockchain Technology in the Field of Digital Forensics: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Goals

- Identify key blockchain-based forensic approaches by examining how blockchain’s core properties are leveraged to secure and streamline digital forensic investigations across various sub-domains.

- Highlight limitations or open issues with blockchain-based forensic approaches.

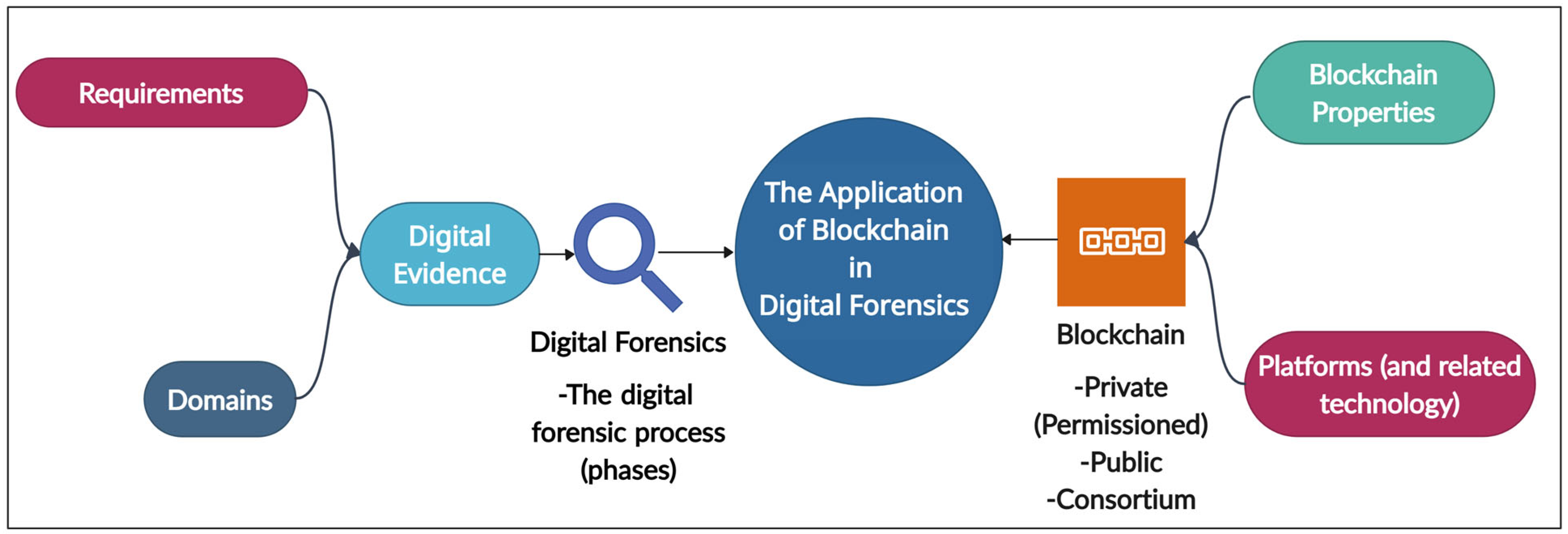

- Propose a structured representation of findings through a visual schema that can serve as a conceptual framework that illustrates blockchain applications in digital forensics. This will allow researchers to quickly identify and have a holistic understanding of the entire blockchain-in-digital forensics landscape before diving into specifics.

- Answer the following research questions:

- RQ1: How is blockchain technology currently integrated into digital forensics to address its challenges, and what key advantages does its application offer?

- RQ2: What key challenges or limitations do current blockchain-based forensic solutions face, and how do they vary across different digital forensics domains?

1.2. Research Contributions

- -

- Presents a visual representation of the state-of-the-art in blockchain application in the digital forensics field: We offer a visual schema that can serve as a structured conceptual framework that consolidates current findings on blockchain-based digital forensic solutions and highlights both widely explored and relatively understudied avenues.

- -

- Examines practical blockchain approaches of blockchain-based solutions: We investigate blockchain-based solutions (frameworks, methodologies, and tools) proposed or implemented to tackle forensic challenges with a consideration of blockchain types, platforms and blockchain properties explored by the solutions, synthesizing key insights on how these solutions enhance, or could enhance, evidence integrity, privacy, and process automation.

- -

- Identifies open issues and future directions: Our analysis highlights open challenges such as legal admissibility, scalability, and blockchain limitations such as computational costs, thus laying the groundwork for future research and the development of more robust, scalable blockchain-forensics systems.

1.3. Related Works

2. Brief Background Study of Digital Forensics and Blockchain Technology

2.1. Digital Forensics

2.2. The Digital Forensics Process

- Collection: The collection phase, otherwise known as acquisition phase, is the stage where the identified media or devices are collected by practitioners for investigative purposes, and evidence is extracted from the devices. Data are meticulously copied to make forensics copies for investigative purposes, and the authentication of the entire process occurs mainly through cryptographic hashing and time-stamping; finally, documenting the extraction process into a chain of custody occurs to provide integrity from the collection phase [28].

- Preservation: The preservation phase involves maintaining the custody of digital evidence on devices or removable media in a way that prevents any modification or alterations to its content. This phase is important for ensuring that prospective digital evidence remains original and usable in an investigation and retains reliability for legal admissibility [25]. Upholding the preservation methods through the investigation process is crucial in deciding a case.

- Examination: In this phase, practitioners carefully analyze and correlate the extracted digital evidence to find patterns, prove or disprove theories, and uncover relationships or connections that are pertinent to the investigated event [23]. This typically involves interpreting the data, comparing and correlating with other discovered evidence, and applying forensic techniques to determine its relevance.

- Reporting: The DF process culminates in this reporting stage where the investigator compiles and presents the final documentation and summary reports that contain the findings of the investigation, including the investigative steps taken throughout the process [25] to the relevant audience, i.e., a court of law, employers, or cybersecurity teams, etc. This final report relies on a thorough DF investigative process that guarantees a sufficient level of certainty in its objective conclusions.

2.3. Principles of Digital Forensics

- Integrity of Digital Evidence: Digital evidence has a complex nature that often involves issues relating to volatility and anonymity. This has made it very susceptible to integrity losses and, if not properly handled, can lead to the inadmissibility of the evidence in court or sketchy results [29]. The integrity of digital evidence is the most important requirement of the entire forensics process as it is critical to trustworthiness and admissibility of the evidence in a court of law [30]. If the evidence or data have been tampered with or changed in any way during the process, they may be challenged by opposition and rejected by the court, which can sabotage the entire investigation. Typically, examination and analysis is carried out on a replica of the digital media, and the integrity of this replica should also be maintained during the different phases of the investigation process [29]. To prove the integrity of digital evidence, a form of cryptographic hashing [31] is employed on some data at the acquisition stage to generate a unique “digital fingerprint” or signature of that data; this hash can then be compared to the hash of the evidence presented later in the digital forensics process [13]. Requirements like authenticity, security to ensure non-alteration and privacy during preservation and the transmission of digital evidence, and ethical handling are of utmost importance; thus, the forensic examiner must make use of proper tools and techniques to ensure that the data are preserved in the exact form as when they were acquired.

- Chain of Custody (CoC): This involves the sequential documentation and accountability for the custody, management, control, transfer, analysis, and final disposition of assets or evidence from collection to presentation in a court of law [32]. CoC has an important impact since it establishes integrity and safeguards the admissibility of digital evidence in court proceedings due to the volatile and complex nature of digital evidence. In digital forensics, the chain of custody acts like a secure auditable trail [11] ensuring that digital assets—whether physical devices containing evidence or the digital evidence itself—remain accounted for and untampered during the investigation process. It is a meticulous record-keeping system that tracks an asset’s journey from its origin to its destination. This documentation includes essential details such as date, time, location, individuals involved, and any custody transitions. Investigators typically must adhere to strict protocols to safeguard against unauthorized meddling and maintain the asset’s integrity. In simple terms, it is like a protective shield for evidence, ensuring its reliability throughout its entire lifecycle. Requirements of this principle include access control, data provenance, privacy/confidentiality, auditability, process automation, security, transparency, integrity, immutability, storage, and record-keeping [11].

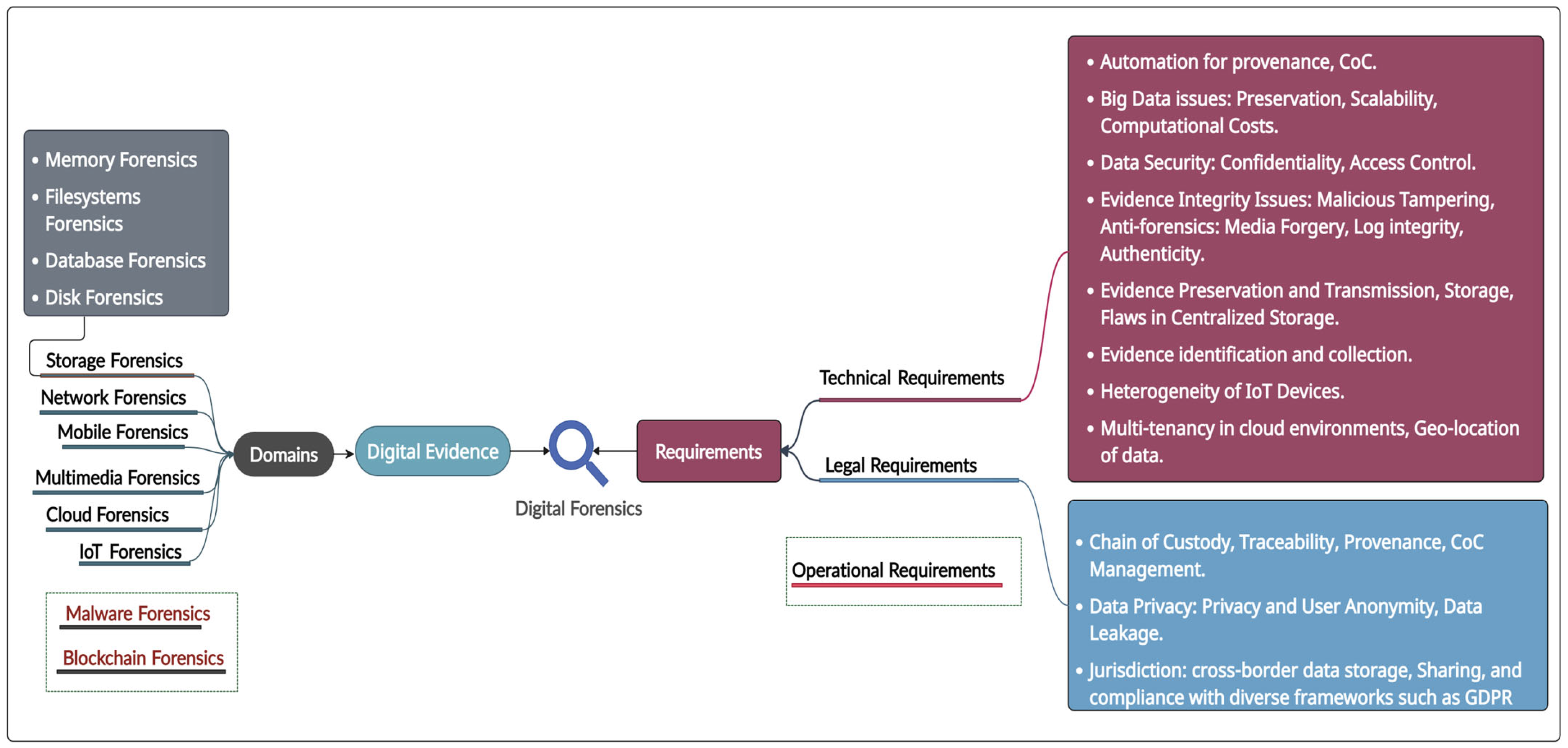

2.4. Requirements and Challenges of Digital Forensics

2.5. Domains of Digital Forensics

2.6. Blockchain

2.7. Blockchain Types

- Public Blockchain: A public blockchain, also referred to as a permissionless blockchain, enables unrestricted participation, allowing anyone to join, create, and update the blockchain through transactions. This open access makes all transactions and data stored on the blockchain visible and accessible to everyone, which can raise privacy concerns in situations where data confidentiality is crucial [68].

- Private Blockchain: A private blockchain, also called a permissioned blockchain, operates with restricted access, allowing only authorized and trusted entities to participate. Unlike public blockchains, private blockchains limit the visibility of the chain data to these trusted participants, which can be advantageous for use cases that require more control and confidentiality [68].

- Consortium Blockchain: A hybrid model that combines elements of both public and private blockchains. This is a permissioned blockchain where participation is restricted to a group of pre-selected members, typically organizations or institutions. Each node represents a participant within the consortium, and the number of nodes is based on the size of the group that governs. Consortium blockchains provide the member institutions with access to the network via gateways, offering features such as member authentication, data access control, transaction monitoring, and member management [69].

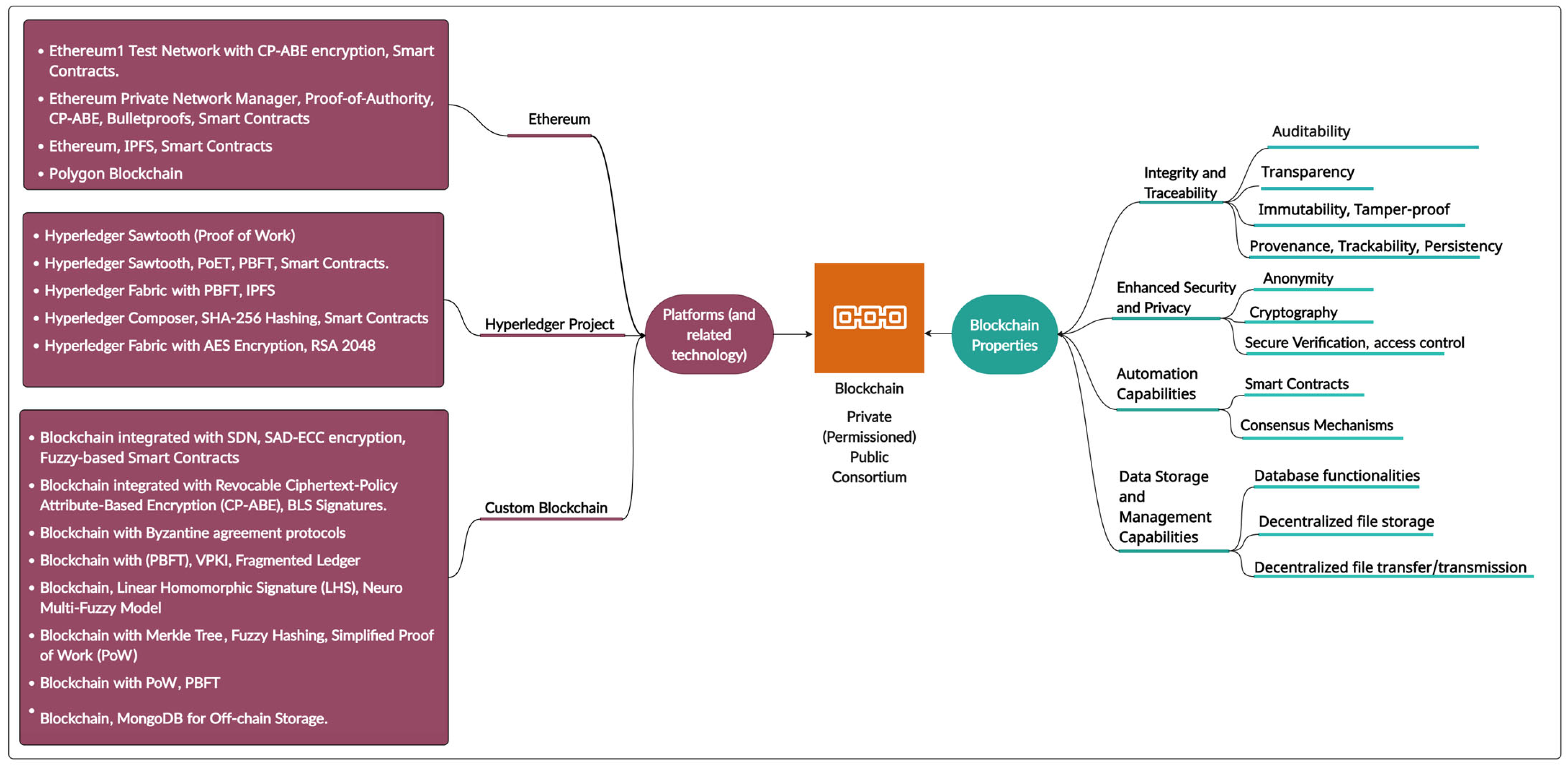

2.8. The Inherent Properties of Blockchain Technology

- Integrity and Traceability Properties: Blockchain technology is established to possess characteristics that ensure trust and accountability of preserved data. These properties include auditability [1], transparency [70], immutability, provenance [4], and a host of other names that describe similar properties in other literature such as coherence, persistency [71], trackability [72], or tamper-proof [2], etc. It is important to note that while blockchain is designed to be highly resistant to tampering, calling it completely immutable is an oversimplification; thus, it is more accurate to say that any changes or attacks are typically highly resource-intensive and highly detectable [73]. However, when all of these properties are considered together, it can guarantee near-complete integrity. Auditability/provenance allows for the verification of transactions, ensuring that all actions can be traced back to their origin, thus verifying authenticity and ownership; immutability ensures that once data are recorded, they cannot be changed discretely, while the transparency property allows for all transactions or changes to be visible to authorized parties, promoting trust, non-repudiation, and accountability.

- Enhanced Security and Privacy: Blockchain technology offers a high level of security and encryption, which creates a layer of trust without needing a centralized intermediary [74]. This is because advanced cryptographic techniques protect the data and transactions on the blockchain. Blockchain employs key cryptographic methods such as public key cryptography, zero-knowledge proofs, and hash functions to ensure data integrity, authenticity, and privacy [75]. It is also established that blockchain enhances anonymity by allowing users to perform transactions without revealing their real-world identities [76]. Public key cryptography provides pseudonymous addresses, zero-knowledge proofs, and a secure verification of smart contracts, which allow for the verification of transactions without disclosing sensitive information [74]. These generated addresses ensure high-level anonymity for both the transactions and actors on blockchain [77]. Furthermore, hash functions ensure the “chain of block” where each block contains a hash value and which connects it to the next block, causing an increased protection of sensitive data as any change in the data will alter the hash, which would affect the overall change [78]; this ability ensures the integrity of data, which is a very important characteristic of blockchain as explained.

- Automation Capabilities: The automation capabilities of blockchain have been highlighted by multiple authors, and these are usually exemplified by (a) smart contracts [79], for instance, the practicability of blockchain for automation was considered in e-government because of its decentralized nature [80]. A smart contract is a digital representation of a relationship or a contractual agreement between different parties that is enforceable by code, without any underlying obligations under the contract [81]. These self-executing contracts with the predefined rules directly written into code enable the automatic execution of agreements when the corresponding pre-defined conditions are met. (b) Consensus mechanisms such as proof-of-work (PoW) or proof-of-stake (PoS), etc., which automate the process of validating and appending transactions to the blockchain [82]. These properties of blockchain speed up transactions and increase efficiency while ensuring that the terms of the agreements are enforced automatically, accurately, and transparently without the need for intermediaries.

- Data Storage and Management Capabilities: Blockchain has been established to possess decentralized file storage and transfer capabilities and database functionalities [83], which allow it to store and manage large volumes of data securely and efficiently. Zhu et al. (2023) established the integration of blockchain into traditional databases through their survey and examined how blockchain contributes to efficient data management and storage [84]. These attributes of blockchain have also been explored to enhance the security and efficiency of file sharing based on the Inter-Planetary File System (IPFS) [85], highlighting the unique characteristics that blockchain brings to data management. Furthermore, the enhanced security and data provenance properties of blockchain make it an ideal solution to ensure trust in databases [86]. Furthermore, these capabilities allow blockchain to serve as a robust database solution that can handle diverse data types while ensuring data integrity, accessibility, and decentralized storage for chain of custody especially, which further enhances the reliability and security of the system.

3. Systematic Literature Review

3.1. Objectives and Scope

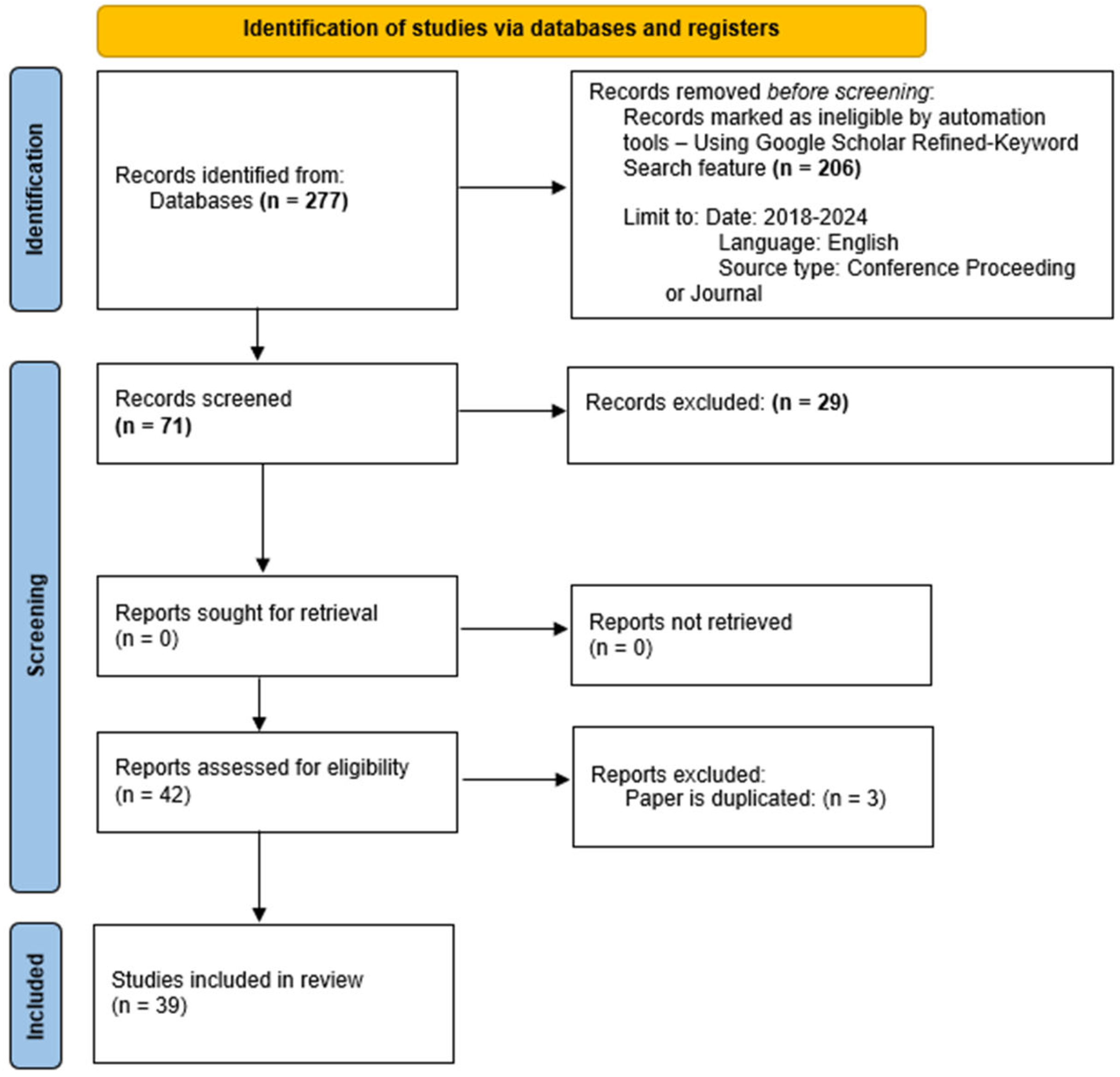

3.2. SLR Research Protocol

3.2.1. Search Strategy

3.2.2. Literature Selection Criteria

3.2.3. Selection of Results

3.2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3.3. Results of Systematic Literature Review

4. Summary of Primary Study

5. State of the Art in Blockchain Application in the Field of Digital Forensics: A Visual Schema

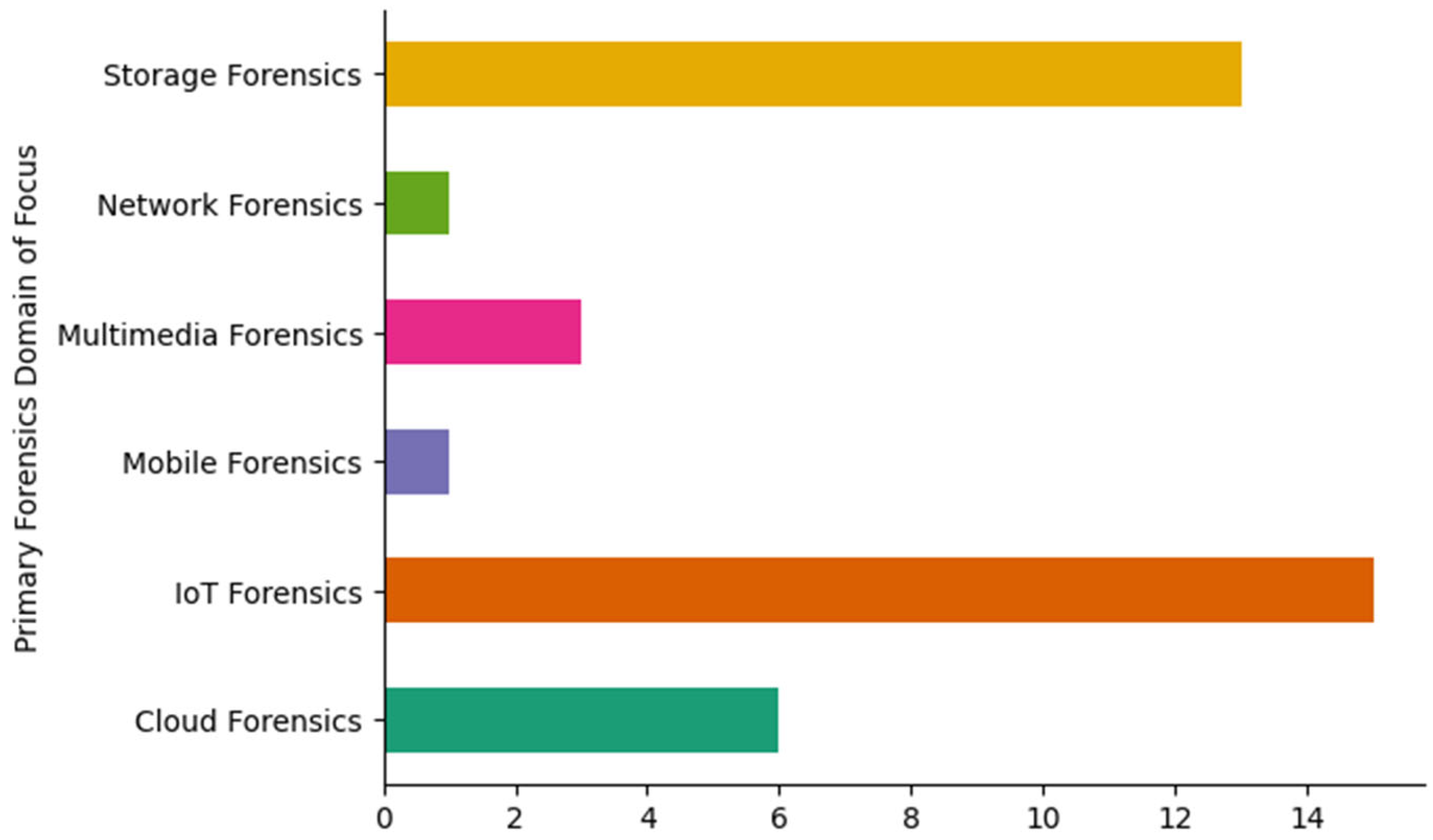

5.1. Digital Forensics Domains Explored

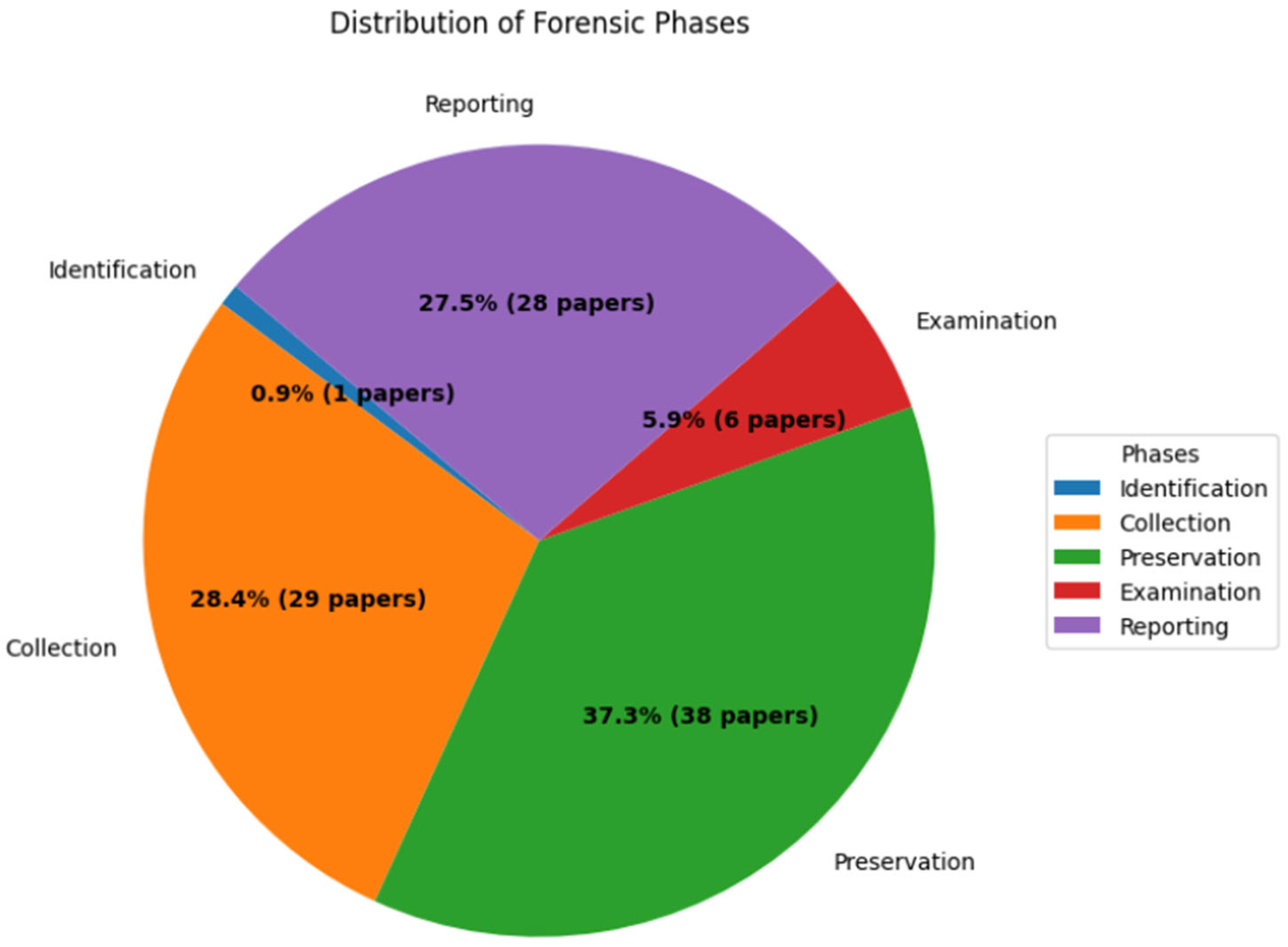

5.2. Digital Forensics Phases Explored

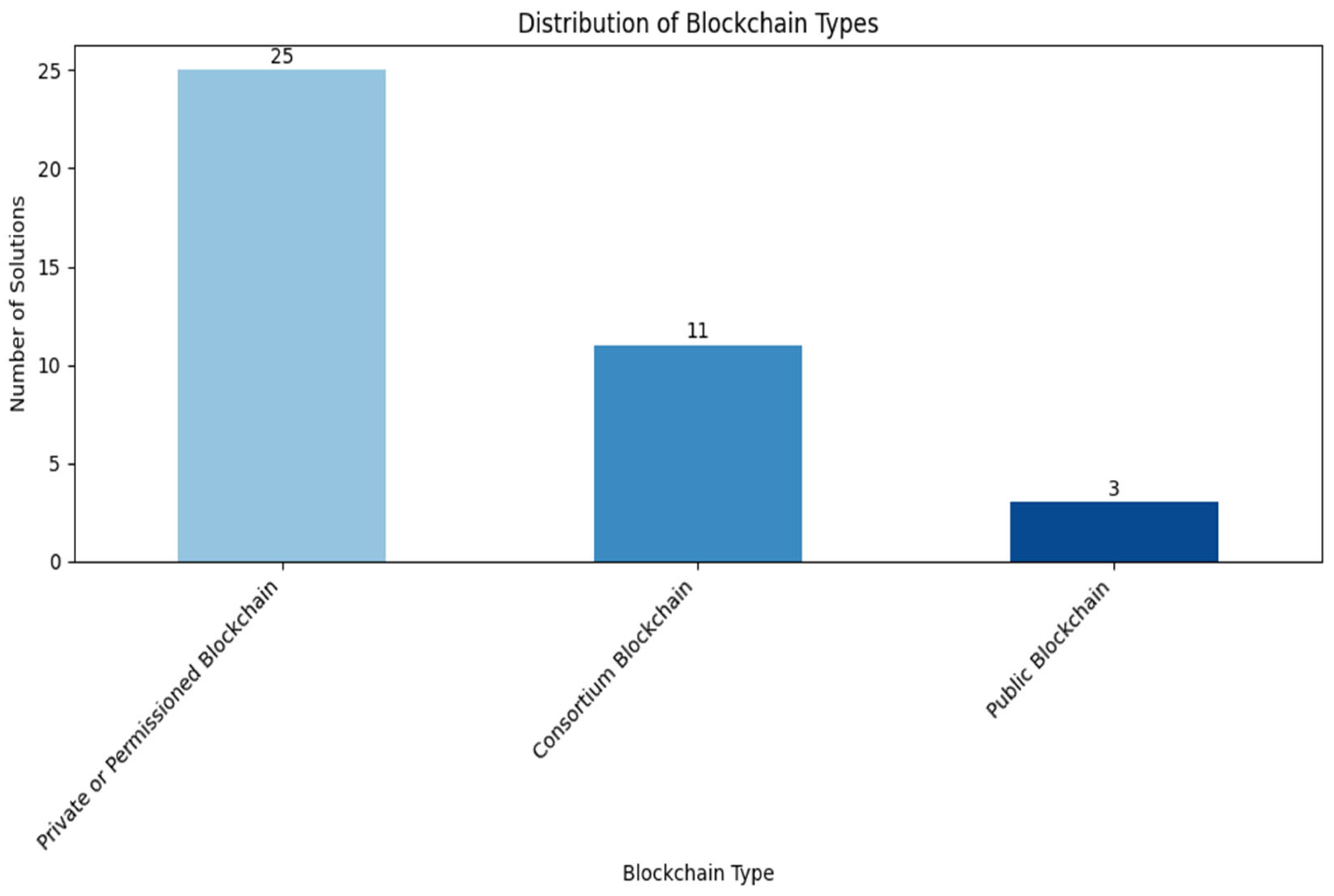

5.3. Blockchain Type Utilized

5.4. Blockchain Platforms Utilized

6. Discussion of Results

6.1. RQ1: How Is Blockchain Technology Currently Integrated into Digital Forensics to Address Its Challenges, and What Key Advantages Does Its Application Offer?

6.1.1. Blockchain-Driven Enhancements to Forensic Principles: Enhancing Evidence Integrity and Chain of Custody

6.1.2. Applications Across IoT, Cloud, and Emerging Domains

6.1.3. Strengthening Storage Forensics

6.1.4. Automating Forensic Processes

Key Advantages of Blockchain Integration in Digital Forensics

6.2. RQ2: What Key Challenges or Limitations Do Current Blockchain-Based Forensic Solutions Face, and How Do They Vary Across Different Digital Forensics Domains?

7. Open Issues and Future Research Direction

7.1. Narrowed Focus of Existing Research

7.2. Lack of Studies in Malware Forensics

7.3. Lack of Studies in Blockchain Forensics

7.4. Neglect of Operational Requirements in Digital Forensics

7.5. Ethical Implications of Blockchain in Digital Forensics

8. Limitations of Research

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dasaklis, T.K.; Casino, F.; Patsakis, C. Sok: Blockchain solutions for forensics. In Technology Development for Security Practitioners; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.K.; Rana, A.K.; Rana, S.K.; Sharma, V.; Lilhore, U.K.; Khalaf, O.I.; Galletta, A. Decentralized model to protect digital evidence via smart contracts using layer 2 polygon blockchain. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 83289–83300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khateeb, H.; Epiphaniou, G.; Daly, H. Blockchain for modern digital forensics: The chain-of-custody as a distributed ledger. In Blockchain and Clinical Trial: Securing Patient Data; Springer: Cham, Switherland, 2019; pp. 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M. Applications of blockchain in digital forensics and forensics readiness. In Blockchain for Cybersecurity and Privacy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 339–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah, S.S. Understanding blockchain technology. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2018, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselgren, A.; Kralevska, K.; Gligoroski, D.; Pedersen, S.A.; Faxvaag, A. Blockchain in healthcare and health sciences—A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 134, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, J.; Yang, H.; Ma, X. Supply chain finance innovation using blockchain. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 67, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Saha, R.; Lal, C.; Conti, M. Internet-of-Forensic (IoF): A blockchain based digital forensics framework for IoT applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 120, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbi, A.; MacDermott, Á.; Ismael, A.M. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based Internet of Things (IoT) forensic investigation process models. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2022, 42, 301470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanji, S.; Alfandi, O.; Ahmad, L.; Kakkengal, L.; Al-Kfairy, M. A systematic analysis on the readiness of Blockchain integration in IoT forensics. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2022, 42, 301472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, D.; Mangeth, A.L.; Frajhof, I.; Alves, P.H.; Nasser, R.; Robichez, G.; Silva, G.M.; Miranda, F.P.d. Exploring blockchain technology for chain of custody control in physical evidence: A systematic literature review. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlam, H.F.; Ekuri, N.; Azad, M.A.; Lallie, H.S. Blockchain Forensics: A Systematic Literature Review of Techniques, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Electronics 2024, 13, 3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Årnes, A. Digital Forensics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sachowski, J. Implementing Digital Forensic Readiness: From Reactive to Proactive Process; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, M.; Marnerides, A.; Johnson, C.; Pezaros, D. A survey on industrial control system digital forensics: Challenges, advances and future directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1705–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Palmbach, T.; Miller, M.T. Henry Lee’s Crime Scene Handbook; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, B.; Spafford, E. An event-based digital forensic investigation framework. In Proceedings of the Digital Forensic Research Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 11–13 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, F.B. Digital Forensic Evidence Examination; Asp Press Livermore: Livermore, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, B.; Choo, K.-K.R. An integrated conceptual digital forensic framework for cloud computing. Digit. Investig. 2012, 9, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, M.D.; Eloff, M.M.; Eloff, J.H. Integrated digital forensic process model. Comput. Secur. 2013, 38, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Norwawi, N.M.; Raman, V. Internet of Things (IoT) digital forensic investigation model: Top-down forensic approach methodology. In Proceedings of the 2015 Fifth International Conference on Digital Information Processing and Communications (ICDIPC), Sierre, Switzerland, 7–9 October 2015; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Prayudi, Y.; Riadi, I. Digital Forensics Workflow as A Mapping Model for People, Evidence, and Process in Digital Investigation. Int. J. Cyber-Secur. Digit. Forensics 2018, 7, 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Atlam, H.F.; Hemdan, E.E.-D.; Alenezi, A.; Alassafi, M.O.; Wills, G.B. Internet of things forensics: A review. Internet Things 2020, 11, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Le-Khac, N.-A.; Scanlon, M. Evaluation of digital forensic process models with respect to digital forensics as a service. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.01730. [Google Scholar]

- Ajijola, A.; Zavarsky, P.; Ruhl, R. A review and comparative evaluation of forensics guidelines of NIST SP 800-101 Rev. 1: 2014 and ISO/IEC 27037: 2012. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Internet Security (WorldCIS-2014), London, UK, 8–10 December 2014; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Horsman, G. The COLLECTORS ranking scale for ‘at-scene’digital device triage. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsman, G.; Sunde, N. Unboxing the digital forensic investigation process. Sci. Justice 2022, 62, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Solms, S.; Louwrens, C.; Reekie, C.; Grobler, T. A control framework for digital forensics. In Proceedings of the Advances in Digital Forensics II: IFIP international Conference on Digital Forensics, National Center for Forensic Science, Orlando, FL, USA, 29 January–1 February 2006; pp. 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, S. Protecting the Integrity of Digital Evidence and Basic Human Rights During the Process of Digital Forensics. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.H.; Sharma, P.K.; Jo, J.H.; Park, J.H. A blockchain-based decentralized efficient investigation framework for IoT digital forensics. J. Supercomput. 2019, 75, 4372–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussev, V. Hashing and data fingerprinting in digital forensics. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2009, 7, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopade, M.; Khan, S.; Shaikh, U.; Pawar, R. Digital forensics: Maintaining chain of custody using blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2019 Third International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud)(I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 12–14 December 2019; pp. 744–747. [Google Scholar]

- Karie, N.M.; Venter, H.S. Taxonomy of challenges for digital forensics. J. Forensic Sci. 2015, 60, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, A.; Mehrotra, V.; Goel, S.; Naman, K.; Maurya, S.; Agarwal, R. Developing trends and challenges of digital forensics. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Networks (ISCON), Mathura, India, 22–23 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Spathoulas, G.P.; Anagnostopoulos, M.; Ghosal, A.; Borocz, I.; Solanas, A.; Conti, M.; Patsakis, C. Research trends, challenges, and emerging topics in digital forensics: A review of reviews. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 25464–25493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, M.; Brighi, R. Digital Forensics: Best Practices and Perspective. In Digital Forensic Evidence: Towards Common European Standards in Antifraud Administrative and Criminal Investigations; Collezione di Giustizia Penale; Wolters Kluwer/CEDAM: Milano, Italy, 2021; pp. 13–48. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhaqm, A.; Ikuesan, R.A.; Kebande, V.R.; Abd Razak, S.; Grispos, G.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Al-Rimy, B.A.S.; Alsewari, A.A. Digital forensics subdomains: The state of the art and future directions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 152476–152502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.D.; Norman, J. An analysis of digital forensics in cyber security. In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Cognitive Computing: AICC 2018, Hyderabad, India, 2–4 February 2018; pp. 701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Yaacoub, J.-P.A.; Noura, H.N.; Salman, O.; Chehab, A. Digital forensics vs. Anti-digital forensics: Techniques, limitations and recommendations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.17028. [Google Scholar]

- Case, A.; Richard, G.G., III. Memory forensics: The path forward. Digit. Investig. 2017, 20, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghmehchi Firoozjaei, M.; Habibi Lashkari, A.; Ghorbani, A.A. Memory forensics tools: A comparative analysis. J. Cyber Secur. Technol. 2022, 6, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligh, M.H.; Case, A.; Levy, J.; Walters, A. The Art of Memory Forensics: Detecting Malware and Threats in Windows, Linux, and Mac Memory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Malin, C.; Casey, E.; Aquilina, J. Malware Forensics Field Guide for Windows Systems; Syngress: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, B. File System Forensic Analysis; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhaqm, A.; Abd Razak, S.; Othman, S.H.; Ali, A.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Rosman, A.S.; Marni, N. Database forensic investigation process models: A review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 48477–48490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K. Data Breach Preparation and Response: Breaches Are Certain, Impact Is Not; Syngress: Rockland, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, I.; Davies, G.; Pringle, N.; Blyth, A. The impact of hard disk firmware steganography on computer forensics. J. Digit. Forensics Secur. Law 2009, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilli, E.S.; Joshi, R.C.; Niyogi, R. Network forensic frameworks: Survey and research challenges. Digit. Investig. 2010, 7, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Tunio, S.; Akhtar, F.; Wajahat, A.; Nazir, A.; Ullah, F. Network Forensics: A Comprehensive Review of Tools and Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacoub, J.-P.A.; Noura, H.N.; Salman, O.; Chehab, A. Advanced digital forensics and anti-digital forensics for IoT systems: Techniques, limitations and recommendations. Internet Things 2022, 19, 100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riadi, I.; Umar, R.; Firdonsyah, A. Identification Of Digital Evidence On Android’s Blackberry Messenger Using NIST Mobile Forensic Method. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. (IJCSIS) 2017, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Brunty, J. Mobile device forensics: Threats, challenges, and future trends. In Digital Forensics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Verdoliva, L. Media forensics and deepfakes: An overview. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2020, 14, 910–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sencar, H.T.; Verdoliva, L.; Memon, N. Multimedia Forensics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bourouis, S.; Alroobaea, R.; Alharbi, A.M.; Andejany, M.; Rubaiee, S. Recent advances in digital multimedia tampering detection for forensics analysis. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarthanan, T.; Bagheri, M.; Zargari, S. IoT forensics: An overview of the current issues and challenges. In Digital Forensic Investigation of Internet of Things (IoT) Devices; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 223–254. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanova, M.; Nikoloudakis, Y.; Panagiotakis, S.; Pallis, E.; Markakis, E.K. A survey on the internet of things (IoT) forensics: Challenges, approaches, and open issues. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 1191–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manral, B.; Somani, G.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Conti, M.; Gaur, M.S. A systematic survey on cloud forensics challenges, solutions, and future directions. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnaye, P.; Kulkarni, V. A comprehensive study of cloud forensics. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.; Malin, C.H.; Aquilina, J.M. Malware Forensics: Investigating and Analyzing Malicious Code; Syngress: Burlington, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lohachab, A.; Garg, S.; Kang, B.; Amin, M.B.; Lee, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, X. Towards interconnected blockchains: A comprehensive review of the role of interoperability among disparate blockchains. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M. Blockchain for Dummies (2nd IBM Li); Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wüst, K.; Gervais, A. Do you need a blockchain? In Proceedings of the 2018 Crypto Valley Conference on Blockchain Technology (CVCBT), Zug, Switzerland, 20–22 June 2018; pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, S.S.; Syed, T.A. ForensicTransMonitor: A Comprehensive Blockchain Approach to Reinvent Digital Forensics and Evidence Management. Information 2024, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.S.; Vecchio, M.; Putra, G.D.; Kanhere, S.S.; Antonelli, F. A decentralized peer-to-peer remote health monitoring system. Sensors 2020, 20, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebe, M.; Erdin, E.; Akkaya, K.; Aksu, H.; Uluagac, S. Block4forensic: An integrated lightweight blockchain framework for forensics applications of connected vehicles. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, R.; Hemdan, E.E.-D.; El-Fishway, N. A review study on blockchain-based IoT security and forensics. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 36183–36214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, M.S.; Chowdhury, M.J.M.; Hoque, M.A. A survey of consensus algorithms in public blockchain systems for crypto-currencies. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 182, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Ye, J.; Murimi, R.; Wang, G. A survey on consortium blockchain consensus mechanisms. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.12058. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.-V.; Hsu, C.-L. A systematic literature review of blockchain technology: Security properties, applications and challenges. J. Internet Technol. 2021, 22, 789–802. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, G.; Sharma, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Ahmad, I.; Qureshi, S.; Ishfaq, M. Blockchain technology: Benefits, challenges, applications, and integration of blockchain technology with cloud computing. Future Internet 2022, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, B.K.; Panda, S.S.; Jena, D. An overview of smart contract and use cases in blockchain technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Bangalore, India, 10–12 July 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhknecht, F. Talking blockchains: The perspective of a database researcher. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 37th International Conference on Data Engineering Workshops (ICDEW), Chania, Greece, 19–22 April 2021; pp. 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, R.; Liu, L. Security and privacy on blockchain. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2019, 52, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, X. A survey on blockchain technology and its security. Blockchain: Res. Appl. 2022, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Mu, Q.; Yang, B.; Yu, Y. Secure pub-sub: Blockchain-based fair payment with reputation for reliable cyber physical systems. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 12295–12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.-N.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Blockchain challenges and opportunities: A survey. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2018, 14, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, R.; Alex, A. A review on blockchain security. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP: Bristol, UK, 2018; p. 012030. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.N.; Loukil, F.; Ghedira-Guegan, C.; Benkhelifa, E.; Bani-Hani, A. Blockchain smart contracts: Applications, challenges, and future trends. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2021, 14, 2901–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassen, M. Blockchain and e-government innovation: Automation of public information processes. Inf. Syst. 2022, 103, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, J.; Hein, A.; Weking, J.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. Process automation on the blockchain: An exploratory case study on smart contracts. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 5 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Li, K.; Xiao, L.; Cai, J.; Liang, W.; Castiglione, A. A systematic review of consensus mechanisms in blockchain. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Li, B.; Chang, W.; Jia, Z.; Shen, Z.; Shao, Z. A survey of blockchain data management systems. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. (TECS) 2022, 21, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, J.; Zhong, Z.; Yue, C.; Zhang, M. A Survey on the Integration of Blockchains and Databases. Data Sci. Eng. 2023, 8, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Yang, W.; Zheng, J. Blockchain private file storage-sharing method based on IPFS. Sensors 2022, 22, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatal, S.; Rane, J.; Patel, D.; Patel, P.; Busnel, Y. Fileshare: A blockchain and ipfs framework for secure file sharing and data provenance. In Advances in Machine Learning and Computational Intelligence: Proceedings of ICMLCI 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 825–833. [Google Scholar]

- Keele, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; EPSRC: Swindon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Shaikh, A.A.; Laghari, A.A. IoT with multimedia investigation: A secure process of digital forensics chain-of-custody using blockchain hyperledger sawtooth. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 10173–10188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, W.A.; Farouk, M.; Darwish, S.M. An enhanced blockchain-based IoT digital forensics architecture using fuzzy hash. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 151327–151336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Miao, J. A novel blockchain-based digital forensics framework for preserving evidence and enabling investigation in industrial Internet of Things. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 86, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, S.; Dixit, A. BlockSLaaS: Blockchain Assisted Secure Logging-as-a-Service for Cloud Forensics. In Security and Privacy: Second ISEA International Conference, Proceedings of the ISEA-ISAP 2018, Jaipur, India, 9–11 January 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ragu, G.; Ramamoorthy, S. A blockchain-based cloud forensics architecture for privacy leakage prediction with cloud. Healthc. Anal. 2023, 4, 100220. [Google Scholar]

- Pourvahab, M.; Ekbatanifard, G. Digital forensics architecture for evidence collection and provenance preservation in iaas cloud environment using sdn and blockchain technology. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 153349–153364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Shen, J.; Cao, Z.; Dong, X. Blockchain based digital evidence chain of custody. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Blockchain Technology, Hilo, HI, USA, 12–14 March 2020; pp. 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; He, J.; Xuan, X. A data preservation method based on blockchain and multidimensional hash for digital forensics. Complexity 2021, 2021, 5536326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lal, C.; Conti, M.; Hu, D. LEChain: A blockchain-based lawful evidence management scheme for digital forensics. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 115, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lone, A.H.; Mir, R.N. Forensic-chain: Blockchain based digital forensics chain of custody with PoC in Hyperledger Composer. Digit. Investig. 2019, 28, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, D.; Bartolomei, B. Digital forensics and privacy-by-design: Example in a blockchain-based dynamic navigation system. In Privacy Technologies and Policy: 7th Annual Privacy Forum, APF 2019, Rome, Italy, 13–14 June 2019, Proceedings 7; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Lal, C.; Conti, M.; Alazab, M.; Hu, D. Eunomia: Anonymous and secure vehicular digital forensics based on blockchain. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2021, 20, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, T.; Abouyoussef, M. Towards Privacy-Preserving Vehicle Digital Forensics: A Blockchain Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS), San Antonio, TX, USA, 29–30 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Philip, A.O.; Saravanaguru, R.K. Smart contract based digital evidence management framework over blockchain for vehicle accident investigation in IoV era. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 4031–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, S.; Fu, K. Tfchain: Blockchain-based trusted forensics scheme for mobile phone data whole process. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 6th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC), Chongqing, China, 4–6 March 2022; pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, G.; Xin, J.; Wang, Q.; Ni, X.; Guo, X. Research on IoT Forensics System Based on Blockchain Technology. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 4490757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.-C. The application of blockchain of custody in criminal investigation process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 192, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusetti, M.; Salsi, L.; Dallatana, A. A blockchain based solution for the custody of digital files in forensic medicine. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2020, 35, 301017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuson-David, K.; Al-Hadhrami, T.; Alazab, M.; Shah, N.; Shalaginov, A. BCFL logging: An approach to acquire and preserve admissible digital forensics evidence in cloud ecosystem. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 122, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.; Sharma, S.; Mohan, S. Blockchain enabled intelligent digital forensics system for autonomous connected vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Communication, Computing and Internet of Things (IC3IoT), Chennai, India, 10–11 March 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.; Fernandes, S.; Raorane, S.; Syed, S. A novel approach for digital evidence management using blockchain. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Computational Techniques (IC-RACT), Raigad, India, 27–28 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.A.; Uddin, M.; Shaikh, A.A.; Laghari, A.A.; Rajput, A.E. MF-ledger: Blockchain hyperledger sawtooth-enabled novel and secure multimedia chain of custody forensic investigation architecture. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 103637–103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunianto, E.; Prayudi, Y.; Sugiantoro, B. B-DEC: Digital evidence cabinet based on blockchain for evidence management. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2019, 181, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, P.T.; Do Hoang, H.; Khanh, N.B.; Pham, V.-H. Sdnlog-foren: Ensuring the integrity and tamper resistance of log files for sdn forensics using blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th NAFOSTED Conference on Information and Computer Science (NICS), Hanoi, Vietnam, 12–13 December 2019; pp. 416–421. [Google Scholar]

- Pourvahab, M.; Ekbatanifard, G. An efficient forensics architecture in software-defined networking-IoT using blockchain technology. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 99573–99588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothukuri, V.; Cheerla, S.S.; Parizi, R.M.; Zhang, Q.; Choo, K.-K.R. BlockHDFS: Blockchain-integrated Hadoop distributed file system for secure provenance traceability. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaletey, E.; Parizi, R.M.; Zhang, Q.; Choo, K.-K.R. BlockIPFS-blockchain-enabled interplanetary file system for forensic and trusted data traceability. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain), Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 July 2019; pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sakshi; Malik, A.; Sharma, A.K. Blockchain-based digital chain of custody multimedia evidence preservation framework for internet-of-things. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2023, 77, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarpala, L.; Casino, F. A blockchain-based forensic model for financial crime investigation: The embezzlement scenario. Digit. Financ. 2021, 3, 301–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Saraswat, D.; Tanwar, S. NyaYa: Blockchain-based electronic law record management scheme for judicial investigations. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 63, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Ma, H.; Ding, B.; Wang, H.; Shi, P. Subtraction of Hyperledger Fabric: A blockchain-based lightweight storage mechanism for digital evidences. J. Syst. Archit. 2024, 153, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L.; Shreelekshmi, R. Edwards curve digital signature algorithm for video integrity verification on blockchain framework. Sci. Justice 2024, 64, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apirajitha, P.; Devi, R.R. A novel blockchain framework for digital forensics in cloud environment using multi-objective krill Herd Cuckoo search optimization algorithm. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2023, 132, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.S.; Feng, T. Using blockchain to ensure the integrity of digital forensic evidence in an iot environment. EAI Endorsed Trans. Creat. Technol. 2022, 9, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, D.; Gill, N.S.; Gulia, P.; Yahya, M.; Ahanger, T.A.; Hassan, M.M.; Abdallah, F.B.; Shukla, P.K. A secure digital evidence preservation system for an iot-enabled smart environment using ipfs, blockchain, and smart contracts. Peer–Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M.R.; Ghahyazi, A.E. A Conceptual Blockchain-Based Framework for Secure Industrial IoT Remote Monitoring: Proof of Concept. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 139, 1071–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotsis, S.; Kolokotronis, N.; Limniotis, K.; Shiaeles, S.; Kavallieros, D.; Bellini, E.; Pavué, C. Blockchain solutions for forensic evidence preservation in IoT environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Network Softwarization (NetSoft), Paris, France, 4–28 June 2019; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, J.; Islam, R.; Mahboubi, A.; Islam, M.Z. A State-of-the-Art Review of Malware Attack Trends and Defense Mechanism. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 121118–121141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, T.M.; Suresh, A.; Bhargavi, S.; Reddy, M.H.V.; Nikhil, K.S.; Priya, G.C. Enhancing Crypto Transaction Security: A Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Electrical Energy Systems (ICEES), Chennai, India, 22–24 August 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Related Work | Multiple Digital Forensics Domains | Challenges or Limitations of Blockchain-Based Solutions | Blockchain Type | Blockchain Platform | Blockchain Properties of Interest | Visual Schema of Blockchain Application to Digital Forensics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akinbi et al. [9] | Only IoT | × | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Khanji et al. [10] | Only IoT | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × |

| Batista et al. [11] | × | × | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| Dasaklis et al. [1] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | × | × |

| Atlam et al. [12] | ✓ | ✓ | × | × | ✓ | × |

| Our SLR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Requirements of Digital Forensics | Challenges in Digital Forensics | Description of Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Requirements | Vast Volumes of Data (Big Data) | Handling and processing large datasets efficiently, which complicates analysis. Issues related to decentralized data, data accessibility and management during investigation, data duplication, heterogeneity of data and data sources, etc. |

| New and Emerging Technologies and Devices | Challenges posed by new digital devices and technologies such as Cloud, IoT, AI, Smart Contract Vulnerabilities, etc. This includes difficulties in extracting data from small and embedded devices as well as data dispersed across multiple platforms, cloud environment, and diverse formats. | |

| Security of Digital Evidence | Issues relating to preservation of integrity evidence tampering, confidentiality (data leakage and access control), and availability of digital evidence. | |

| Instability of Digital Evidence (Time Sensitivity) | Issues related to the transient and volatile nature of digital data, making timely collection crucial. Concerns over the durability and degradation of storage media. | |

| Anti-Forensics Techniques | Methods that make it difficult to conduct forensic analysis and increase sophistication in cybercriminal methods cause the need for high computational resources and thus lead to more cost for tools, time needed per investigation, etc. | |

| Network Forensic Analysis Tools | Improving the functionalities of tools for traffic sniffing, analyzing encrypted network data, intrusion detection, protocol analysis, and Security Event Management (SEM). | |

| Forensics Process Automation | High reliance on manual processes in forensic investigations. This means a need for automating forensic tasks to improve efficiency. | |

| Legal Systems Requirements | Jurisdiction | Legal complications arising from cross-border data storage, exchange, and/or access, as well as inconsistent legal protocols across jurisdictions. |

| Admissibility of Digital Forensic Methods and Tools | Ensuring forensic methods are legally accepted. | |

| Privacy and Ethical Concerns | Balancing investigative needs with privacy rights. | |

| Chain of Custody | Ensuring integrity, provenance, reliability, and proper documentation of evidence from collection to presentation. Access control and evidence-tampering concerns. | |

| Omission of Terms and Conditions in Service Level Agreements (SLAs) | Lack of forensic provisions in SLAs with tech service providers. | |

| Operational Requirements | Inadequate Knowledge Sharing and Communication among experts | Inefficiencies in sharing and communication of forensic expertise and findings. |

| Forensic Investigator Licensing Requirements | Need for formal certification and regulation of forensic investigators. | |

| Challenge of Digital Forensic Preparedness in Organizations | Ensuring organizations are prepared for forensic investigations through resource allocation, policies, processes, guidelines, and procedures. | |

| Training Gaps | Shortage of trained and certified digital forensic experts. Continuous need for updated training to keep pace with technological advancements. | |

| Incidence Detection, Response, and Prevention | Challenges in identifying and mitigating digital incidents in organizations. |

| Database Search Strategy | |

|---|---|

| Keywords | “Blockchain Digital Forensics”, “Blockchain”, “Digital Forensics”, “Computer Forensics”, “Blockchain-based digital forensics”, “Blockchain-based forensics”, “Blockchain Application Digital Forensics”, “Legal investigation”, “Judicial investigation”, “digital investigation”, “digital enquiry”, “Litigation” |

| Linking words | “and”, “in”, “for”, “with”, “to” |

| Identified blockchain properties used as keywords | “immutability”, “integrity”, “traceability”, “resilience”, “security”, “privacy”, “automation”, “smart contracts”, “decentralized”, “peer-to-peer”, “chain”, “auditability”, “trust”, “decentralized storage” |

| Scope | 2003–2025 (Until January) |

| Databases and Search Engines | MDPI, SpringerLink, ACM digital library, ResearchGate, Scopus Search Engine (Science Direct), Google Scholar |

| Last date searched | 9 January 2025 |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| The selected paper must be relevant to blockchain technology application to digital forensics and the digital forensics investigation process regardless of the specific digital forensics’ domain. | The paper focuses on the application of digital forensic processes to investigate blockchain technology. |

| The paper must provide a practical or theoretical application of blockchain to the digital forensics investigation process. | The paper falls outside the broader field of blockchain technology application to digital forensics and digital forensics investigation process. |

| The paper must not be a review or survey paper or other studies. | The paper does not discuss concepts, models, or frameworks integrating blockchain technology to digital forensics. |

| The paper must be peer-reviewed. | Papers that are not peer-reviewed. |

| The paper must be written in English. | Papers not written in English and duplicates of published papers. |

| The paper must be published in a conference proceeding or journal. | Grey literature (white papers, editorial comments, book reviews, government documents, and blog posts). |

| The paper must be within 2018–2025. | Papers that are outside the years 2018–2025. |

| Primary Study | Summary of Contribution | Blockchain-Driven Enhancements to Forensic Principles | Drawbacks or Challenges of Approach | Primary Digital Forensics Domain in Focus | Primary Phase(s) Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS1—Khan et al. [89] | This study introduces a framework leveraging Hyperledger Sawtooth to enhance real-time video surveillance in multimedia forensics. By integrating blockchain with IoT, it ensures secure chain-of-custody management and addresses issues like frame filtering and object-of-interest identification. Smart contracts streamline validation processes, and immutable distributed storage (IPFS) improves evidence handling. Performance evaluations indicate notable resource efficiency and reduced consumption. | Evidence Integrity: Data Preservation and Transmission Integrity, Access Control; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Immutability | This solution still faces challenges, which include significant computational demands and bandwidth requirements for handling real-time multimedia data, along with the complexity of implementing automated processes for filtering and identification. | Multimedia Forensics | Collection, Preservation |

| PS2—Mahrous et al. [90] | This paper proposes a framework for IoT digital forensics that incorporates fuzzy hashing into a blockchain-based architecture. The fuzzy hash technique improves evidence detection by enabling the identification of variations in digital evidence while enhancing data integrity through Merkle trees and a simplified proof-of-work consensus mechanism. The framework also handles heterogeneity in IoT devices and explores forensic analysis on resource-constrained systems. | Evidence Integrity: Data Integrity, Evidence Collection; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Provenance | Issues that this framework still grapples with include scalability issues, which arise due to the increased computational and storage demands of processing large volumes of IoT data on the blockchain, particularly in real-time scenarios. Additionally, integrating fuzzy hashing adds computational overhead. | IoT Forensics | Identification, Collection |

| PS3—Xiao et al. [91] | This paper presents a framework for digital forensics in the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) using blockchain technology. The framework introduces a novel batch consensus mechanism based on an improved delegated proof-of-stake (DPoS) algorithm, enabling tamper-proof, non-repudiable, and real-time storage of evidence. A token-based access control mechanism enhances security and ensures efficient retrieval of evidence. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Data Security; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Provenance; Access Control | The limitation of this approach centers around scalability issues as data volumes grow to big data levels in IIoT systems, whereas the proposed model is currently limited to simulated environments, requiring real-world testing for broader applicability. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation |

| PS4—Rana et al. [2] | This paper proposes a model leveraging the Layer 2 Polygon blockchain and IPFS for decentralized storage and management of digital evidence. Smart contracts automate access control, ensuring tamper-proof evidence handling. The model enhances transparency, reduces reliance on centralized authorities, and facilitates multi-country investigations. | Evidence Integrity: Data Integrity, Tamper Resistance; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Access Control | Limitations in this approach include vulnerabilities in smart contracts, a potential of 51% attacks, Sybil attacks, which involve creating multiple nodes to launch cyberattacks, and the scalability of managing increasing evidence volumes in real-world applications. | Storage Forensics | Collection, Reporting |

| PS5—Rane and Dixit [92] | The approach presented by this paper is the BlockSLaaS, a blockchain-assisted secure logging-as-a-service framework for cloud forensics. The solution uses a private-permissioned blockchain to ensure a tamper-proof chronological recording of logs, thereby preserving their integrity and confidentiality. Fine-grained access controls allow forensic investigators to retrieve logs securely while addressing multi-stakeholder collusion problems. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Log Integrity; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Access Control | The model faces challenges related to scalability in handling vast volumes of cloud generated logs, potential system delays, and the computational overhead of cryptographic operations. | Cloud Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Examination |

| PS6—Ragu and Ramamoorthy [93] | This paper proposes cloud forensics architecture integrating Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and blockchain technologies for privacy leakage prediction. The system leverages SAD-ECC encryption, fuzzy-based smart contracts, and Logical Graphs of Evidence (LGoE) to enhance evidence collection, analysis, and reporting in IaaS cloud environments. The architecture ensures secure, decentralized data storage and processing while addressing data provenance and traceability challenges. | Evidence Integrity: Data Integrity, Provenance; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Automation | Scalability issues due to the growing volume of evidence, computational overhead from complex cryptographic techniques, and the potential latency in forensic workflows. | Cloud Forensics | Identification, Collection, Preservation, Examination, Reporting |

| PS7—Pourvahab and Ekbatanifard [94] | This paper presents DFeSB, a digital forensic architecture integrating Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and blockchain technologies for evidence collection, provenance preservation, and forensic analysis in IaaS cloud environments. The system employs SA-DECC encryption, fuzzy-based smart contracts (FSCs), and Logical Graph of Evidence (LGoE) for comprehensive forensic processes. It ensures tamper-proof evidence storage, secure user authentication, and traceable evidence provenance. | Evidence Integrity: Data Integrity, Provenance; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Ownership Proof | Challenges of this architecture include scalability issues due to large-scale evidence volumes, high computational costs that are needed for the cryptographic algorithms, and latency in evidence verification workflows. | Cloud Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Examination, Reporting |

| PS8—Yan et al. [95] | This paper proposes a blockchain-based protocol for managing the chain of custody of digital evidence. The protocol integrates ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) for secure access control, BLS signature for group consensus and verification, and blockchain for maintaining an immutable, traceable record of evidence creation, transfer, and storage. The approach emphasizes balancing privacy and traceability while ensuring evidence integrity and validity. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Transparency | Scalability issues arise from the increased computational and communication demands of the consensus mechanism as the size of groups and the number of transactions grow. These challenges can lead to delays in reaching consensus and broadcasting transactions to all nodes in the network. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Collection, Examination |

| PS9—Liu et al. [96] | This paper presents a model that uses blockchain and multidimensional hash algorithms to preserve digital evidence securely. The model introduces dual custody chains: a branch chain for individual cases and a main chain for overarching integrity using multidimensional hashing. The model ensures high levels of automation, minimizes human intervention, and strengthens the chain of custody for digital forensics applications. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Provenance; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Automation | Challenges that this model face revolve around computational overhead issues due to multidimensional hashing and heavy encryption approach, also potential inefficiency in scalability when managing large volumes of evidence and users. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Collection |

| PS10—Li et al. [97] | This paper proposes LEChain, a lawful evidence management framework using blockchain to secure the entire chain of custody in digital forensics. It incorporates randomizable signatures for witness privacy, CP-ABE for fine-grained access control, and PoA consensus on a consortium blockchain for managing evidence records. It also integrates juror voting during court trials with a privacy-preserving mechanism. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Access Control | In the LEChain, scalability issues arise due to the significant computational resources required for cryptographic operations like CP-ABE and randomizable signatures. Additionally, the PoA consensus mechanism can introduce high communication overhead as the network grows, potentially causing delays. The complexity of managing multiple stakeholders with varying access levels further complicates real-world deployment. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Reporting |

| PS11—Lone and Mir [98] | This paper proposes forensic chain, a blockchain-based model implemented using Hyperledger Composer to strengthen the chain of custody in digital forensics. The model incorporates evidence creation, transfer, deletion, and display functions to ensure the integrity, traceability, and authenticity of digital evidence throughout its lifecycle. The system uses a permissioned blockchain to securely store metadata and logs related to evidence transactions. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Immutability | Scalability challenges may be experienced as a result of the limited throughput of Hyperledger Composer blockchain platform when there is large volume of data to be processed. It also faces challenges of high computational overhead for managing large volumes of evidence, and the complexity of real-time integration with existing forensic tools. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Reporting |

| PS12—Cebe et al. [66] | This paper proposes a lightweight blockchain-based framework called Block4Forensic (B4F) for vehicular forensics. The framework leverages Vehicular Public Key Infrastructure (VPKI) for membership management and privacy preservation and uses a fragmented ledger approach to reduce blockchain storage overhead. By storing hashes of data in a shared ledger and maintaining detailed information in fragmented ledgers, the framework ensures evidence integrity and privacy while facilitating efficient accident analysis. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Privacy Preservation | Scalability challenges could arise from managing membership and fragmented ledger synchronization with millions of vehicles. Additionally, the framework lacks mechanisms for ensuring the availability of critical forensic data in cases of participant failures. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation |

| PS13—Billard and Bartolomei [99] | This paper presents a blockchain-based navigation system for IoT-enabled vehicles, emphasizing digital forensics and privacy by design. Their proposed prototype leverages Hyperledger Fabric to ensure pseudonymized storage of GPS data for traffic analysis while maintaining user privacy under GDPR compliance. The system supports forensic investigations by providing immutable, non-repudiable logs of navigation history. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Privacy Preservation | This approach faces limitations concerning the practical challenges of integrating the blockchain-based system with existing vehicular systems. Furthermore, potential security vulnerabilities and risks associated with pseudonymized data patterns persist such as the inability to guarantee the accuracy of submitted data and privacy risks around the probability of identifying users through data patterns remains. | IoT Forensics | Preservation, Examination |

| PS14—Li, Chen et al. [100] | This paper introduces Eunomia, a vehicular digital forensics (VDF) framework leveraging a consortium blockchain to ensure privacy, accountability, and traceability. The framework models investigations as finite state machines executed through smart contracts, enabling evidence management and traitor tracing. Data confidentiality is maintained using CP-ABE and Bulletproofs, while pseudonymous identities safeguard user privacy. The framework is evaluated using an Ethereum-based prototype. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Confidentiality; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Privacy Preservation | Scalability issues arise from computational and communication overheads in cryptographic operations (e.g., CP-ABE and Bulletproofs). Additionally, pseudonymity risks user identity exposure through data patterns, and the system complexity poses integration challenges. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Examination |

| PS15—Menard and Abouyoussef [101] | This paper proposes a privacy-preserving vehicular digital forensics (VDF) strategy utilizing a consortium blockchain and group signatures. The strategy ensures user anonymity while maintaining traceability in cases of misconduct. Two ledgers are used: one for general vehicular data and another for evidence. Performance evaluations demonstrate low computational overhead and efficient communication. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Anonymity, Privacy Preservation | Limitations of this model include potential scalability issues in managing two ledgers with increasing vehicle and evidence data. Computational overhead from cryptographic operations like group signatures may affect real-time processing in larger networks. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation |

| PS16—Philip and Saravanaguru [102] | This paper proposes a smart contract-based digital evidence management framework for vehicle accident investigations on the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) era. The framework integrates blockchain and InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) to collect, preserve, and manage evidence from vehicles, neighboring devices, and infrastructure. Dynamic access control is implemented using smart contracts, ensuring data sharing among stakeholders such as law enforcement and insurance providers. The framework is evaluated for performance and cost-efficiency in both public and private blockchain environments. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Access Control | Limitations of this framework include high computational and communication overhead when deploying smart contracts on public blockchains, as well as scalability concerns existing as well because as accident-related data grows, the storage and retrieval of evidence on the blockchain and IPFS require substantial computational resources, which may lead to bottlenecks. Also, the dependence on IPFS pinning services for long-term evidence storage introduces external risks if it cannot be sustained. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation, |

| PS17—Hu et al. [103] | This paper proposes TFChain, a blockchain-based trusted forensics scheme for the entire lifecycle of mobile phone data. By integrating memory analysis and blockchain technology, the framework ensures the authenticity, timeliness, and traceability of evidence. It minimizes manual intervention by automating evidence collection, storage, and analysis while maintaining security through Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) on Hyperledger Fabric. Evidence is stored in IPFS, with blockchain maintaining metadata and transaction records. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability, Auditability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Automation | Scalability limitations arise due to increased storage demands and computational resources for IPFS and PBFT as evidence volume grows. Reliance on off-chain storage (IPFS) introduces dependency risks and potential delays in data retrieval. Additionally, the scheme relies on a trusted authority, which could be a single point of failure. | Mobile Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS18—Liang et al. [104] | This paper presents a blockchain-based IoT forensics system that integrates alliance chains and distributed storage to improve the integrity and traceability of IoT evidence. The framework supports evidence collection, analysis, and reporting while ensuring data security and access control through blockchain technology. A case study on drone forensics demonstrates the applicability of the system in real-world scenarios. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Access Control | The framework faces scalability issues as the IoT data volumes grows, straining the distributed storage systems and leading to potential bottlenecks in storage and retrieval. Additionally, the reliance on IoT convergence devices introduces a single point of failure as these devices are responsible for data aggregation and validation before uploading to the blockchain. If compromised it could result in the loss of evidence integrity, risking the forensic process. Furthermore, ensuring the security and synchronization of alliance chain nodes across different jurisdictions adds complexity to deployment. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS19—Tsai [105] | This paper proposes a blockchain-based chain of custody framework implemented on a private Ethereum blockchain to enhance digital evidence management. The framework uses smart contracts to enforce role-based access control, ensuring secure evidence collection, transfer, and verification across the preliminary investigation, case management, and court phases. The framework’s immutability and traceability features strengthen the admissibility of digital evidence in judicial proceedings. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Access Control | The framework faces scalability challenges, particularly as the volume of digital evidence grows, increasing computational demands on Ethereum nodes. Also, there is the issue of managing cross-border case sharing, which introduces complexities in synchronizing data across different jurisdictions. | Storage Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS20—Lusetti et al. [106] | This paper proposes a blockchain-based solution for the custody of digital forensic files in forensic medicine, using Hyperledger Fabric. The solution incorporates a hybrid cryptographic system (AES and RSA) to encrypt and securely store digital evidence in redundant online storage while ensuring traceability via a private blockchain. It enables role-based access management and records all user actions on the blockchain to maintain evidence integrity and access transparency. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Confidentiality; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Access Control | Scalability challenges stem from managing large volumes of digital files and user operations on the blockchain. The system also depends heavily on the proper deployment of secure hardware, such as USB devices and tamper-resistant modules. The study also highlights that compatibility of this solution with varying legal frameworks across jurisdictions may be complex. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Reporting |

| PS21—Awuson-David et al. [107] | This paper proposes a Blockchain Cloud Forensic Logging (BCFL), a framework for acquiring and preserving log evidence in cloud ecosystems. The framework, which is built on Hyperledger Fabric, ensures tamper-proof evidence collection and traceability using smart contracts and distributed ledger technology. BCFL also addresses compliance with GDPR by maintaining an auditable chain of custody for evidence. The framework’s effectiveness is demonstrated through a case study in a simulated cloud environment. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Access Control | Scalability concerns exist due to increased demands on the distributed ledger as cloud log inevitably grows. Also, reliance on a single simulated environment rather than operational cloud ecosystems raises questions about real-world applicability especially as different cloud environments exist. | Cloud Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS22—Tyagi et al. [108] | This paper proposes a blockchain-enabled intelligent digital forensics system for autonomous connected vehicles (ACVs). The system combines blockchain with AI to collect, analyze, and report digital evidence while maintaining privacy and security. It utilizes short randomizable signatures for witness anonymity, ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CP-ABE) for access control, and a distributed ledger for immutable evidence storage. The framework supports multi-stakeholder collaboration in ACV incident investigations. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Immutability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Privacy Preservation | High computational and communication overhead due to cryptographic operations like CP-ABE and randomizable signatures. Scalability concerns also arise with large-scale data from numerous sensors, and nodes in ACV ecosystems are considered. Finally, since real-time data processing in the distribution system is implemented, it may introduce some delay. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS23—Rao et al. [109] | This paper introduces a blockchain-based digital evidence management system for maintaining the chain of custody (CoC). The system ensures tamper-proof evidence handling from collection to presentation in court by storing evidence records in a private blockchain and enforcing integrity through cryptographic hashes. The proposed system supports evidence tracking, validation, and synchronization across participants in a forensic investigation. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Auditability | Scalability challenges arise as the volume of evidence grows, increasing storage and synchronization demands on the blockchain. The reliance on private blockchains limits interoperability with external systems and raises trust concerns in multi-stakeholder scenarios. | Storage Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS24—Khan et al. [110] | This paper introduces MF-Ledger, a blockchain-enabled multimedia forensic investigation architecture built on Hyperledger Sawtooth. The architecture supports the collection, preservation, and analysis of multimedia evidence, leveraging smart contracts for automated processes and maintaining the chain of custody through an immutable and distributed ledger. The system incorporates Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) and Proof of Elapsed Time (PoET) consensus mechanisms to ensure security and scalability. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Transparency | This approach faces scalability challenges, which stem from its ability to handle large multimedia files and integrate distributed storage solutions. Furthermore, additional computational overhead is introduced due to the use of PBFT and PoET consensus mechanisms. Further, managing stakeholder coordination in a decentralized environment adds complexity. | Multimedia Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS25—Yunianto et al. [111] | This paper presents B-DEC (Blockchain Digital Evidence Cabinet), a blockchain-based digital evidence management system designed to secure the chain of custody (CoC). Built on Ethereum private blockchain, the system integrates smart contracts for automating access control and ensuring evidence integrity. B-DEC enhances the traditional Digital Evidence Cabinet (DEC) by adding features such as evidence splitting, detailed logging, and JSON-based structured CoC documentation for forensic investigations. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Auditability, Transparency | Scalability concerns arise from the increased computational requirements and storage needs for managing the resulting complex CoC structures. Additionally, this prototype requires high GAS fees, and some execution delays persist, which could impede real-time evidence management. Finally, the lack of standardization across digital evidence formats is an issue that may impede the integration with real-word applications. | Storage Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS26—Duy et al. [112] | This paper proposes the SDNLog-Foren system, a blockchain-based log management system for Software Defined Networking (SDN) forensics. The system integrates Hyperledger Fabric to ensure tamper resistance and integrity of log files used in forensic investigations. SDNLog-Foren employs log filtering, segmentation, and distributed ledger storage to manage and preserve log evidence securely while providing fine-grained access control for investigators. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Auditability; Chain of Custody: Traceability, Transparency | The system faces concerns with scalability due to the high volume of log data generated in SDN environments, which can overwhelm the blockchain’s transaction handling and storage capacity. This will lead to slower performance as the size of the ledger grows larger. Also, managing frequent transactions and syncing them across multiple blockchain nodes increases latency and computational overhead. | Network Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS27—Kumar et al. [8] | This paper proposes the Internet-of-Forensics (IoF) framework, a blockchain-based digital forensics system designed for IoT applications. The framework integrates a hierarchical blockchain structure with chain of custody (CoC), evidence chain (EC), and case chain (CC) to ensure transparency, traceability, and integrity of evidence. It leverages lattice-based cryptography for post-quantum security and efficient computation. The system addresses cross-border legal challenges through consortium blockchain. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Transparency, Automation | Scalability concerns arise due to the growing number of IoT devices and the increasing size of blockchain records, which can lead to storage and processing delays. Additionally, the high computational cost of lattice-based cryptographic operations and synchronization issues in cross-border consortium blockchain setups still poses challenges that need to be handled such as diverse legal frameworks across regions and time zone differences. | IoT Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS28—Pourvahab and Ekbatanifard [113] | This paper proposes a forensics architecture for SDN-IoT environments integrating blockchain technology to address challenges such as evidence tampering, traceability, and chain of custody (CoC) management. The system uses the Linear Homomorphic Signature (LHS) algorithm for device authentication and a Neuro Multi-Fuzzy classifier for packet analysis. Logs and evidence are stored immutably in the blockchain, ensuring transparency and accountability for forensic investigations. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Automation | Managing extensive log data and computational requirements for the LHS algorithm and Neuro Multi-Fuzzy model poses scalability concerns. Also, integration with existing SDN-IoT infrastructure is complex, and the distributed nature of the architecture may lead to synchronization delays in evidence updates across nodes. | Network Forensics | Collection, Preservation, Reporting |

| PS29—Mothukuri et al. [114] | This paper proposes BlockHDFS, a blockchain-integrated Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) for secure provenance traceability. By using Hyperledger Fabric, the system records file metadata, such as hash values, access times, and modification times, in an immutable blockchain ledger. This ensures tamper-proof logging, allowing investigators to trace file changes and verify evidence integrity during forensic investigations. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Transparency | Performance overheads occur in metadata extraction and blockchain logging processes, particularly during high data loads. This indicates scalability issues likely arising due to increasing metadata size and synchronization demands as file volumes grow. Also, the periodic execution of the NodeJS client introduces potential delays in real-time applications. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Reporting |

| PS30—Nyaletey et al. [115] | This paper proposes BlockIPFS, a blockchain-integrated Interplanetary File System (IPFS) for enhancing forensic traceability and secure data sharing. By utilizing Hyperledger Fabric, the system logs metadata, such as file hashes, access timestamps, and owner details in an immutable ledger, while raw files remain on the IPFS network. The solution provides clear audit trails for forensic investigations and authorship protection, ensuring accountability and privacy in distributed file systems. | Evidence Integrity: Tamper Resistance, Traceability; Chain of Custody: Provenance, Transparency | Managing large volumes of metadata and synchronizing blockchain logs introduces significant overhead that can impact system efficiency. Furthermore, the framework lacks robust mechanisms to restrict access to file hashes outside the blockchain, which may lead to unauthorized sharing. The execution of smart contracts also adds computational complexity, affecting overall performance. | Storage Forensics | Preservation, Reporting |