Abstract

This study analyzes the differences in the selection of teaching methodologies, assessment instruments, and educational values in Master’s Theses (TFMs) written within the Geography and History specialization of a Teacher Training Master’s program in Spain. The aim is to examine how these pedagogical components vary according to the gender of the author and the educational level targeted by the instructional proposals. A mixed-methods approach was applied combining statistical analysis (Chi-square and ANOVA tests) with qualitative content analysis of 54 anonymized TFMs. The results indicate that while gender-related differences were not statistically significant in most categories, qualitative patterns emerged: female authors tended to adopt more reflective, participatory approaches (e.g., oral expression, gender visibility), whereas male authors more often used experiential or gamified strategies. Significant differences by educational level were found in the use of gamification, inquiry-based learning, and project-based learning. A progressive increase in methodological complexity was observed from lower secondary to upper levels. In terms of educational values, interdisciplinarity and inclusion were most frequently promoted, with critical perspectives such as historical memory and gender visibility more prevalent at the Baccalaureate level. These findings underscore the TFM’s role as a space for pedagogical innovation, reflective practice, and value-driven teacher identity formation.

1. Introduction

Being a teacher requires not only a strong vocational calling but also the development of didactic skills that enable educators to effectively transmit essential knowledge to students, thereby facilitating successful learning throughout the teaching–learning process. This process should, in turn, equip students with the skills, knowledge, and attitudes necessary for their future integration into the labor market. To this end, the Master’s Degree in Secondary Education Teaching (Máster Universitario en Formación del Profesorado en Secundaria) was launched in the 2009–2010 academic year, replacing the former Pedagogical Aptitude Certificate (Curso de Certificación de Adaptación Pedagógica, CAP) [1].

The structure of this Master’s program was designed within the framework of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and is based on a training model that emphasizes pedagogical competencies, methodological innovation, and formative assessment [2].

While the program is now well-established, its initial implementation was not without difficulties. The 2009–2010 academic year was characterized by organizational, structural, and coordination challenges, primarily due to insufficient planning and a lack of consensus among the responsible institutions. Benarroch [3] reports that these issues led to delays in the program’s rollout across several universities and negatively influenced students’ perceptions. In a similar vein, Benarroch, Cepero, and Perales [4] underscore the lack of coordination between university departments and secondary education centers, which hindered the early development of the program. Likewise, Viñao [5] notes that institutional coordination problems and the difficulty of integrating theoretical and practical components undermined the overall quality of teacher training.

The integration of the Master’s Thesis (Trabajo de Fin de Máster, TFM) into the Master’s in Teacher Training has posed a significant challenge—not only for students, but also for academic programs—as it requires the development of both research and pedagogical competencies within the teacher education process [6]. Several studies have highlighted students’ difficulties in conducting educational research, emphasizing the need to strengthen methodological training [7,8].

Despite these challenges, the Master’s Thesis has increasingly been recognized as a valuable space for pedagogical reflection and innovation. As noted by Breda, Font, Lima, and Pereira [9], it goes beyond a formal academic requirement by enabling future educators to critically analyze their own teaching practices and substantiate the relevance of their didactic proposals. In this sense, the Master’s Thesis has become a key instrument for fostering research-oriented thinking and academic reflection in initial teacher education [10]. Along these lines, Ahmad Abu Aser et al. [11] argue that a more strategic and structured approach to thesis design could better align teacher education programs with the demands of contemporary educational systems.

A central figure in this process is the thesis supervisor. As Mateo-Valdehíta et al. [10] emphasize, the supervisor’s role extends beyond academic advising to include personalized mentoring that supports students throughout the research process. Similarly, Gil and Segura [12] advocate for the use of digital tools to facilitate effective interaction between supervisors and students, thereby enhancing continuous supervision. The supervisor’s responsibility thus encompasses both academic and personal dimensions of guidance. This is consistent with the findings of Lizandra [13], who highlights the benefits of virtual mentoring to improve the organization, motivation, and communication of students during thesis supervision.

Nonetheless, persistent challenges remain, particularly in relation to access to research resources, training in data analysis, and preparation for the oral defense [14]. In this context, studies such as that by García-Antelo and Casal-Otero [15] have examined the use of digital platforms such as virtual campuses, highlighting their potential to provide effective, individualized support during the development of undergraduate and postgraduate theses (TFG/TFM). Strengthening supervision, deepening the exploration of research topics, and refining assessment methodologies are essential steps to enhance the academic and professional impact of the Master’s Thesis.

In terms of the competencies acquired by students, some studies have indicated that, although students tend to evaluate their training positively, there are notable shortcomings in the practical application of acquired knowledge and in professional collaboration [16]. This highlights the underlying need to incorporate active methodologies and reflective approaches into the Teacher Training Master’s program in order to align its content with the real demands of teaching practice [4,17]. This need aligns with the principles of the competency-based approach in higher education, which emphasizes the integration of knowledge, skills, and values as essential pillars for effective teacher education [18]. In light of this, it is essential to consider gender as a dynamic and intersectional social construct that shapes educational experiences, professional expectations, and pedagogical practices. Gender not only influences how future teachers are socialized into the profession but also affects their access to mentorship, evaluation processes, and the perceived legitimacy of their educational designs [19,20]. As Warin and Gannerud [20] argue, the historical feminization of teaching has led to the undervaluation of care-based pedagogies, reinforcing gendered assumptions about what constitutes educational quality. Furthermore, educational research must examine how such assumptions impact the choice of active methodologies, assessment strategies, and educational values [21,22].

These considerations are especially pertinent in teacher education programs, where pedagogical decisions intersect with sociocultural identities. As Vanner, Holloway, and Almanssori [23] argue, these decisions regarding methodologies, values, and assessment are not neutral but are shaped by gendered expectations and roles. Their intersectional analysis reveals how care-oriented approaches—often embraced by women—are undervalued, while male-coded pedagogical styles are legitimized as more “rigorous” or “academic.”

For example, gender-based attributional ambiguity—a phenomenon in which individuals are unsure whether their experiences are shaped by their gender—has been identified as a significant barrier in academic environments [21]. Likewise, the rise of non-binary and gender-diverse identities among students and educators demands that teacher education research move beyond binary conceptions of gender [20].

This focus gains particular relevance in the context of History and Geography education, which plays a central role in shaping critical citizenship, historical memory, and the understanding of sociopolitical values. As Greco [22] and Carvalho [21] emphasize, the pedagogical approach adopted in these subjects can either challenge or reproduce hegemonic narratives, making it essential to analyze how gender intersects with methodological choices, evaluative practices, and value transmission in teacher training.

Consequently, this study adopts an integrated approach that examines how pedagogical choices, values, and assessment practices reflect and reproduce gendered dynamics, contributing to a more inclusive understanding of educational practice and policy.

The Master’s in Teacher Training at Universidad Isabel I has evolved over time and now follows a clearly defined structure. Aware of the value of the Master’s Thesis as a formative tool, the institution established that the thesis should be conceived as a theoretical development grounded in the application of effective educational practices. To this end, four broad thematic lines were defined as foundational pillars to guide thesis development. Based on these, students must choose a specific topic related to curricular content, select a classroom methodology, and identify an appropriate assessment instrument. In parallel, the proposed educational practice must address relevant educational values alongside curricular content.

Although the Teacher Training Master’s at Universidad Isabel I currently offers nine different specializations—namely, Biology and Geology (BIO), Economics and Business Administration (ECO), Physical Education (PE), Vocational Training and Career Guidance (FOL), Geography and History (GH), English (EN), Spanish Language and Literature (SLL), Technology and Computer Science (TCS), and Educational Guidance—this study focuses on a sample from the Geography and History specialization. The goal is to establish generalizable parameters that may be extrapolated to other subject areas.

Therefore, the analyses carried out in this study aim to address the following research hypotheses: What are the most and least frequently selected methodologies in Master’s Theses (TFMs) within the Teacher Training Program specializing in Geography and History? Are there significant differences in methodology selection based on the students’ gender and the educational level at which the best practice is implemented? What assessment tools are chosen by future Geography and History teachers to evaluate the presented best practices? Are there significant differences in the selection of assessment tools according to the teacher’s gender and the educational level? What educational values are promoted in the best practices presented in the TFMs of the Geography and History specialization? Are there significant differences in the values addressed depending on the gender and educational level?

The aim is to identify quantitative and qualitative patterns that reveal differences in the use of methodologies, assessment tools, and underlying educational values according to educational level and the gender of the author. Given that the Teacher Training Master’s program at Universidad Isabel I is offered across the entirety of Spain and has a large student body, this analysis enables a clear understanding of current trends in the training of future teachers who will be active in the coming years.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a mixed-methods research design combining quantitative and qualitative approaches to analyze the teaching methodologies, educational values, and assessment tools employed in Master’s Theses (TFMs) in the Geography and History specialization. This methodological combination enables a more comprehensive understanding of the patterns and pedagogical decisions made by prospective teachers, integrating both measurable trends and narrative justifications.

The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods is supported by Teddlie and Tashakkori [24], who emphasize the value of methodological complementarity in educational research. Similarly, Jordanova [25] underscores the relevance of mixed-methods approaches in historical–educational studies, as they allow researchers to address the complexity of pedagogical practices and documentary analysis. Along these lines, the recent work of Soler and Rosser [26] stands out as a current reference in the application of mixed methods to educational documentation analysis, further reinforcing the validity and applicability of this approach in studies with similar characteristics.

To ensure methodological transparency, the design was structured into four interrelated but distinct phases. This structure does not respond to a longitudinal logic in the strict sense (as no new data were generated across successive time periods), but rather to the need to separate data collection from sequential layers of analysis—descriptive, interpretive, and inferential—each requiring a different level of granularity and validation. The temporal frame for the research process spanned the academic year in which the TFMs were submitted, with data collection and analytical work distributed over successive academic terms. The methodology is divided into four clearly defined phases.

Phase 1. Data Collection

In this phase, 54 Master’s Theses (TFMs) were collected from the Geography and History specialization, corresponding to student teachers working across different educational levels (Compulsory Secondary Education and Baccalaureate). All TFMs were anonymized to ensure the privacy of the authors by assigning a unique identifier to each document. The data collection process was carried out in accordance with the ethical code approved for the institution’s internal research project, thereby ensuring compliance with principles of confidentiality and ethical responsibility in educational research. This study is part of the research project titled “Multidimensional Analysis of Master’s Theses in Active Methodology: A Bibliometric, Quantitative, and Qualitative Study” (code UI1-P1103), approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Isabel I during its meeting on July 16, 2024. The sample includes all TFMs submitted during a single academic year, with each document ranging between 12,000 and 16,000 words—offering a substantial and information-rich foundation for analysis. While all TFMs were produced within a single institution, Universidad Isabel I is a nationally operating university that enrolls students from across Spain. As such, the dataset reflects a diverse range of socio-educational backgrounds and regional contexts, enhancing the representativeness and relevance of the findings. A summary of the distribution of TFMs by gender and educational level is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of TFMs by gender and educational level.

Phase 2. Classification and Coding

The data extracted from the Master’s Theses (TFMs) were organized into three main analytical categories based on the core components of the educational best practices proposed by the students. The classification is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification and coding.

Each TFM was coded according to these three categories, enabling a systematic analysis of the practices selected by future teachers. The coding process combined deductive criteria based on existing theoretical frameworks with an inductive approach to identify relevant emerging patterns in the corpus.

Phase 3. Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative analysis was conducted using webQDA software, a tool specifically developed for organizing, coding, and analyzing unstructured data in social and educational research [27]. This platform enables collaborative work and online access to all project elements, which is particularly beneficial in research involving multidisciplinary teams or geographically dispersed collaborators.

This type of methodological approach has been previously applied in educational research, both in the analysis of formative competencies [28] and in historical–educational studies involving documentary sources [29], reinforcing its methodological suitability for the present investigation.

A mixed coding strategy—both deductive and inductive—was employed to identify and classify the narrative data. Predefined thematic categories were established and subsequently enriched by emerging codes identified during data analysis. The narratives were segmented into meaning units and coded according to a hierarchical system developed within the software.

The qualitative analysis was conducted using webQDA software, a specialized tool for managing unstructured data in social and educational research. Coding followed a mixed approach: initially, thematic categories were defined based on the existing literature (deductive coding) and subsequently refined and expanded through new codes emerging during the reading and interpretation of the texts (inductive coding). Narratives were segmented into meaning units and organized hierarchically into codes and subcodes.

WebQDA supports this structure through the use of “tree codes,” facilitating both initial coding and subsequent triangulation across analytical categories. The software also allows the generation of qualitative frequency matrices (%FA), which served as a bridge between the narrative analysis and the quantitative phase of the study. This process, by enabling code cross-checking and identifying recurring patterns, enhanced the interpretive depth and analytical consistency.

The application of this tool has been methodologically validated in prior educational studies, including those conducted by Soler, Rosser, Merma-Molina, and Rico-Gómez [30], who employed similar coding protocols for analyzing heterogeneous documentary sources. These references underscore the effectiveness of the webQDA environment for systematizing complex qualitative data and reinforce the suitability of its application in the present research.

From this coding process, qualitative frequency matrices (%FA) were generated, which were then used to prepare the data for the subsequent phase of quantitative analysis.

Phase 4. Quantitative Analysis

The quantitative analysis aimed to test the study’s working hypotheses, which focused on identifying statistically significant differences in the selection of teaching methodologies, assessment instruments, and educational values based on two independent variables: the gender of the TFM author and the educational level targeted by the instructional proposal.

All variables under analysis (gender, educational level, type of methodology, type of assessment tool, and educational value) were categorical and nominal in nature. Accordingly, the Chi-square test of independence was used as the primary statistical procedure. This non-parametric test is appropriate for evaluating associations between qualitative variables and determines whether the observed frequency distributions differ significantly from those expected under the assumption of independence. The significance threshold was set at p < 0.05.

The Chi-square test was applied to examine the following hypotheses:

H1:

There are significant differences in the selection of teaching methodologies according to the author’s gender.

H2:

There are significant differences in the selection of teaching methodologies according to the educational level.

H3:

There are significant differences in the selection of assessment instruments according to the author’s gender.

H4:

There are significant differences in the selection of assessment instruments according to the educational level.

H5:

There are significant differences in the educational values promoted according to the author’s gender.

H6:

There are significant differences in the educational values promoted according to the educational level.

Additionally, two complementary exploratory tests were conducted. First, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences in the distribution of TFMs across educational levels. This analysis provided insight into variations in the density of projects per level. Second, a Spearman correlation was applied to identify potential longitudinal trends in the number of TFMs from first year of ESO to second year of Baccalaureate. Although not central to the hypothesis testing, these additional analyses enriched the internal interpretation of the dataset.

All statistical analyses were carried out using the Python programming language (v. 3.X) with specialized libraries including pandas, numpy, and scipy.stats.

3. Results

This section analyzes each of the categories established for the Master’s Theses (TFMs), focusing on the variables of gender and educational level. The analysis is conducted through both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

3.1. Category 1: Teaching Methodology Used

3.1.1. Analysis by Gender

To examine whether gender influences the selection of teaching methodologies in the TFMs, a two-level analysis was conducted. First, a global Chi-square test of independence was applied considering all methodologies as categories within a single variable in order to assess whether there was a significant overall association between the teacher’s gender and the type of methodology employed. This test yielded a result of χ2 = 10.54 (df = 7; p = 0.160), which is not statistically significant. This indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assert that male and female students systematically select different teaching methodologies.

Second, this global approach was complemented by an item-specific analysis. Individual Chi-square tests were applied to each type of methodology to detect any specific gender-based differences. In this case, none of the methodologies showed statistically significant differences (p > 0.05), although experiential learning displayed a marginal trend toward significance (p = 0.071). Taken together, these results suggest a relatively balanced distribution in methodological choices between male and female students, reinforcing the idea that methodological decisions in TFMs are more closely linked to pedagogical goals, didactic strategies, or contextual factors than to gender.

To deepen the interpretation of this quantitative balance and considering that statistical results point to a gender-equitable implementation, qualitative analysis was employed as an essential complement to understand how this equity is reflected in actual teaching practices. Through the narratives found in the TFMs, not only were the selected methodologies identified, but also the pedagogical motivations, discursive orientations, and instructional goals that underpin them. This qualitative approach makes it possible to capture more subtle distinctions—those not visible through statistical analysis—and provides a deeper understanding of how gender and educational level influence the conceptualization and implementation of these teaching strategies. In this regard, the analysis of the most frequently mentioned methodologies in the TFMs reveals interesting patterns according to the gender of the authors.

As shown in Table 3, the distribution of educational methodologies employed in the Master’s Theses (TFMs) is broken down by the gender of the student teachers, expressed in both absolute frequency and relative percentage (%FA). Although the global quantitative analysis did not yield statistically significant differences between male and female participants in terms of methodology selection, certain nuanced patterns emerge and can be better interpreted through qualitative insights.

Table 3.

Frequency and percentage of teaching methodologies by gender.

Among the methodologies most frequently used by both genders, cooperative learning and project-based learning (PjBL) stand out. Cooperative learning appears as the most frequently employed strategy among male (26.77% FA) and female (26.22% FA) authors alike. This suggests a shared perception of the value of collaborative, participatory methods in promoting meaningful learning and inclusive classroom practices.

Narrative excerpts from the TFMs reinforce this finding. One male-authored proposal, for instance, states:

“The School Archaeological Museum, as a pedagogical project, fosters collaborative work and meaningful learning. Through the creation of exhibitions and guided tours organized by students, a direct connection is established between historical content and the school community.”(Male)

This illustrates how cooperative learning serves as a strategy to integrate content knowledge with student agency and community engagement.

Similarly, a female-authored TFM highlights:

“All tasks are carried out in groups of five, strategically formed to ensure diversity and promote peer learning.”(Female)

This underscores that the collaborative model is equally embraced by female teachers as a means to foster diversity, equity, and interaction among students.

Another widely adopted approach is project-based learning (PjBL), which reflects a shared interest in methodologies that integrate theory and practice. In this context, one male-authored TFM notes:

“Project-Based Learning in the first year of Baccalaureate is organized around the creation of educational podcasts. Each term will focus on a specific theme, encouraging collaboration among students at different stages of the academic year. Sessions will be held to design, discuss, and ultimately record a podcast episode.”(Male)

Similarly, a female-authored narrative highlights:

“The proposal is based on the use of Project-Based Learning. Students will create an exhibition on recent Argentine history, working in groups in an autonomous and reflective manner.”(Female)

These examples indicate that both male and female teachers value PjBL as a methodological strategy that empowers students to take an active and critical role in their own learning process.

In terms of methodologies that show notable differences in frequency between genders, even though these differences are not statistically significant, some recurring patterns can still be identified.

Flipped classroom appears more frequently in the choices made by female student teachers (14.75% FA) compared with their male counterparts (8.66% FA). This may reflect a stronger interest among women in promoting student autonomy through digital tools outside the classroom. One narrative highlights this perspective:

“The teacher believes that the flipped classroom method is particularly suitable for teaching History, as there is a wide range of audiovisual resources available. With proper planning and time, it is possible to implement this methodology in specific units, especially those in which students show less interest or face greater difficulty.”(Female)

Gamification also shows a slightly higher frequency among women (21.31% FA) than men (15.74% FA). This may suggest a female preference for innovative strategies that foster student motivation through interactive tools, as illustrated in the following narrative:

“The use of digital games in the classroom is intended to bring History and Geography content closer to the digital environment in which students live. Using educational video games allows students to actively engage in the learning process, fostering motivation and critical thinking.”(Female)

Among male student teachers, this methodology is also used, albeit to a lesser extent. One narrative notes:

“The gamification technique was selected for use in the early stages of the course. Interactive content will be implemented using EdPuzzle and quizzes via Kahoot!”(Male)

In contrast, experiential learning appears to be more common among male authors (10.23% FA) than female authors (1.63% FA), suggesting that male teachers may place greater emphasis on direct, hands-on experiences. This tendency is reflected in the following excerpt:

“The use of active field-based methods allows students to connect theoretical content in Geography with real-world experiences. Students actively participate in analyzing natural and cultural elements, fostering meaningful and contextualized learning.”(Male)

3.1.2. Analysis by Educational Level

The global statistical analysis using the Chi-square test of independence revealed a significant difference in the use of teaching methodologies according to educational level (χ2 = 29.15; df = 35; p = 0.017). This result indicates a dependency between the type of methodology employed and the educational level at which it is implemented. In other words, the distribution of methodologies is not uniform across different academic levels.

However, this overall significance does not directly indicate which specific methodologies or levels are responsible for the observed differences. To address this, a post hoc analysis was conducted using individual Chi-square tests for each methodology to compare their distribution across educational levels.

The results of this item-specific analysis revealed that three methodologies showed statistically significant differences by educational level: gamification (χ2 = 15.27; p = 0.009), inquiry-based learning (χ2 = 14.38; p = 0.013), and project-based learning (PjBL) (χ2 = 13.87; p = 0.016). In contrast, other methodologies such as flipped classroom and cooperative learning did not show significant variation across levels (p > 0.05).

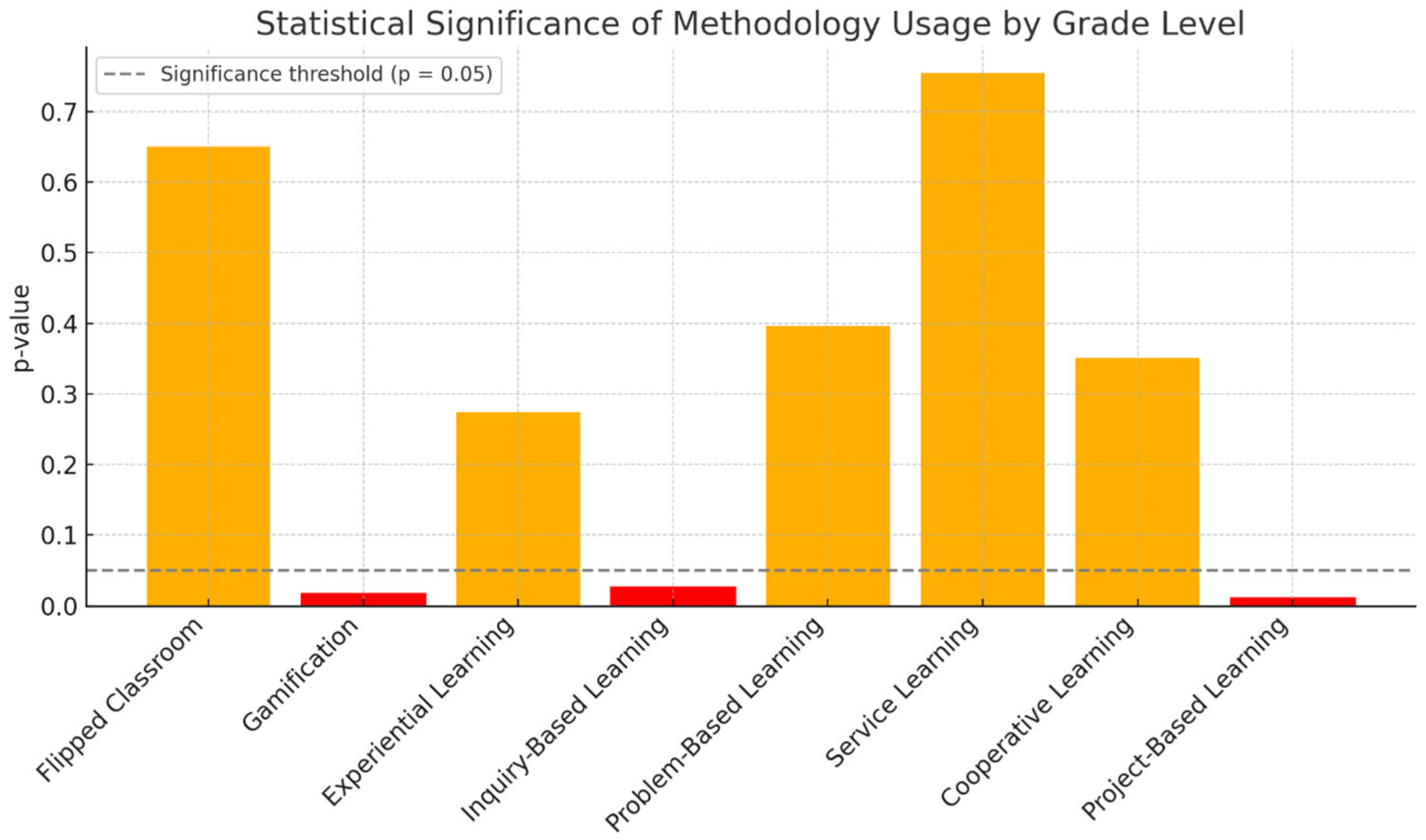

Taken together, these findings indicate that although there is a general relationship between educational level and methodological choice, it is particularly concentrated in three approaches: gamification, inquiry, and project-based learning. These results highlight the need for further exploration into how and why these specific methodologies are adapted differently depending on the course or educational stage. These results are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

p-Values from Chi-square tests assessing the relationship between methodology use and educational level.

The analysis of standardized residuals helped identify the specific educational levels in which certain methodologies were used significantly more or less than expected:

- Gamification was used much more frequently in the fourth year of ESO (residual = 2.43), and significantly less in the third year of ESO (−2.03) and the first year of ESO (−2.16).

- Inquiry-based learning stood out positively in the third year (1.76) and second year of ESO (1.52), and was underused in the second year of Baccalaureate (−1.81).

- Project-based learning (PjBL) was used significantly more in the first year of ESO (1.99) and the second year of Baccalaureate (1.73), and less in the first year of Baccalaureate (−2.45).

As a preliminary step in the qualitative analysis, a quantitative study was conducted to examine the relationship between educational level and the overall use of active methodologies. The global results indicated a statistically significant association between these two variables, prompting a post hoc analysis to determine which specific methodologies were responsible for the observed differences.

However, when applying a Pearson correlation between the total number of methodological applications and the methodological diversity per level, no significant relationship was found (r = 0.35; p = 0.50). This finding suggests that a higher frequency of methodological use does not necessarily imply greater variety in pedagogical approaches. Therefore, it was considered relevant to complement the statistical approach with a qualitative analysis aimed at gaining a deeper understanding of how these methodologies are implemented and adapted according to educational level.

To facilitate a clearer understanding of the data, Table 4 displays the distribution of teaching methodologies across the four levels of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), while Table 5 focuses specifically on the two levels of Baccalaureate. This separation allows for a more precise interpretation of patterns and differences in methodology usage between lower and upper secondary education stages.

Table 4.

Use of teaching methodologies by educational level (frequency and %FA).

Table 5.

Use of teaching methodologies by educational level (frequency and %FA).

The quantitative analysis revealed a significant relationship between the use of active methodologies and educational level (χ2 = 29.15; p = 0.017). While certain methodologies such as cooperative learning and flipped classroom did not exhibit statistically significant differences across levels, others—namely gamification, inquiry-based learning, and project-based learning (PjBL)—showed relevant variations depending on the year group. To gain a deeper understanding of how these methodologies are implemented at each educational level, we turn to the qualitative analysis, where narrative data reveal nuances not captured by quantitative methods.

Cooperative learning is one of the most widely used methodologies across all educational levels, especially in the fourth year of ESO (29.78%), first year of ESO (26.47%), and second year of Baccalaureate (24%). Although no significant quantitative differences were found, the qualitative narratives suggest that its implementation varies depending on the level.

In the early years of ESO, cooperative learning is used primarily as a tool to promote coexistence and collaboration among students:

“Groups of four students are formed, with rotating roles, balanced by gender, to encourage cooperation and reduce performance gaps.”(Male, 1st ESO)

In contrast, at the Baccalaureate level, the approach becomes more academic and argument-driven, emphasizing collaborative knowledge construction:

“Group activities are designed to foster collaborative learning through discussion and problem-solving.”(Male, 2nd Baccalaureate)

Although the frequency of use does not differ significantly across levels, the narratives suggest a qualitative evolution in its application, from basic group structuring in early secondary education to deeper conceptual engagement in upper levels.

Project-based learning (PjBL), on the other hand, shows statistically significant variation across levels (χ2 = 13.87; p = 0.016). It is particularly frequent in the first year of ESO (29.41%), fourth year of ESO (21.27%), and second year of Baccalaureate (24%). The progressive use of this methodology becomes evident in the qualitative narratives as well.

In the lower levels of ESO, project-based learning (PjBL) focuses on concrete and hands-on activities, such as simulations and manual projects:

“The main activity is a simulated archaeological excavation that includes all stages: surveying, digging, cataloguing, and dissemination.”(Male, 1st ESO)

However, in higher levels, the approach shifts toward interdisciplinary and critical projects:

“The student will analyze war propaganda posters from a critical perspective, combining History, Art, and Photography.”(Male, 2nd Baccalaureate)

Thus, PjBL evolves from an experiential, task-oriented approach in lower secondary education to a more complex and analytical application in the upper levels.

Gamification also shows statistically significant differences by educational level (χ2 = 15.27; p = 0.009), with higher usage in the fourth year of ESO (27.65%), first year of Baccalaureate (23.07%), and second year of ESO (19.6%).

In the earlier years, gamification is used primarily to motivate students through simple digital tools:

“A historical trivia game using Kahoot! was designed to review content in a fun and participatory way.”(Male, 2nd ESO)

In contrast, in more advanced courses, gamification takes on a more structured and reflective format:

“An Escape Room will be used as a playful yet critical tool to explore 20th-century art movements.”(Female, 1st Baccalaureate)

This shift suggests that gamification transitions from a motivational tool in lower levels to a strategy for developing critical thinking and analytical skills in upper levels.

Inquiry-based learning also shows statistically significant differences across educational levels (χ2 = 14.38; p = 0.013), with peaks in the third year of ESO and second year of Baccalaureate (20%).

At the ESO level, inquiry tends to be more guided and linked to practical tasks such as information gathering or visual representation:

“The student will research pre-Roman peoples and represent the findings on an interactive map.”(Male, 2nd ESO)

In contrast, at the Baccalaureate level, the inquiry approach becomes more analytical and ethically driven:

“The student will analyze the Argentine dictatorship through testimonies, audiovisual archives, and written sources.”(Female, 1st Baccalaureate)

This evolution reflects a transition from guided inquiry in the lower levels to critical reflection and multidisciplinary analysis in the upper levels.

Flipped classroom shows an overall average usage of 10.4%, with higher frequencies in the second year of Baccalaureate (16%) and in the early years of ESO (11.76%). Although no statistically significant differences were found (p > 0.05), the qualitative data reveal noteworthy pedagogical nuances.

At the ESO level, its implementation focuses on optimizing classroom time:

“Videos will be used to introduce content at home, allowing in-class sessions to focus on practical activities.”(Male, 1st ESO)

In Baccalaureate, the approach becomes more reflective and autonomous, fostering critical thinking:

“Students prepare content at home, and class sessions focus on critical analysis and active participation.”(Male, 2nd Baccalaureate)

3.2. Category 2: Educational Values

3.2.1. Analysis by Gender

A Chi-square test of independence was applied to determine whether there was a significant relationship between the gender of the TFM author and the type of educational value emphasized in their instructional proposals. The results (χ2 = 11.12; df = 7; p = 0.133) indicate that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, as the p-value exceeds the significance threshold (p > 0.05). Consequently, no statistically significant differences were found between male and female authors regarding the educational values they prioritized in their projects. These results suggest that, in this case, the educational approach does not vary meaningfully based on gender.

To further explore these findings, individual Chi-square tests were conducted for each category of educational value, with the aim of identifying whether any specific value showed significant differences by gender. The results showed that none of the educational values analyzed presented statistically significant differences between male and female authors (all p-values > 0.05). These included values such as inclusion, heritage education, gender visibility, peace education, and historical memory, among others. The category closest to the significance threshold was intercultural education, with a p-value of 0.0698, which, although not statistically significant, may warrant a more attentive qualitative exploration of how this value is addressed across genders. Table 6 shows the distribution of educational values by gender.

Table 6.

Educational values by gender (frequency and %FA).

The most prominent educational value in the analyzed TFMs is interdisciplinarity (%FA: 30.76%), reflecting a clear pedagogical commitment to integrated knowledge approaches. This high frequency points to an instructional intention aimed at overcoming curricular fragmentation and connecting different fields of knowledge to foster more meaningful and functional learning.

As one narrative illustrates:

“The proposal combines history, language, ICT, art, and social skills in a comprehensive approach.”(Male, 3rd ESO)

This interdisciplinary perspective allows for the integration of historical, digital, artistic, social, and civic knowledge, facilitating learning that is more closely aligned with students’ real-life contexts. Another teacher notes:

“The proposal integrates competencies in history, geography, language, digital literacy, and teamwork in a cross-curricular approach […] including critical thinking, visual expression, and mobile learning.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

In addition, interdisciplinarity serves as a vehicle for inclusion and motivation, allowing various learning styles to emerge and connect with multiple competencies:

“The card game design includes writing in English, use of Canva, graphic design, chronological sequencing, and historical analysis.”(Male, 4th ESO)

The second most frequent value in the TFMs is inclusion, reflecting the strong sensitivity of future teachers to classroom diversity. Its high frequency demonstrates a sustained concern for ensuring equitable participation of all students, regardless of their abilities, interests, or needs.

This goal is explicitly stated in many proposals:

“Collaborative work is designed as an inclusive and unifying tool that enhances participation for all students.”(Male, 1st ESO)

The inclusive approach is largely grounded in the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and involves adapting materials, group configurations, timing, and roles based on students’ specific needs:

“The proposal encourages diverse student participation through rotating roles […] tailored to their interests, abilities, and learning styles.”(Male, 1st Baccalaureate)

The emotional dimension of inclusion is also highlighted, particularly in cases involving students with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, or anxiety:

“Individualized strategies and active methodologies are incorporated to support inclusive education […] visual thinking and collaborative work facilitate learning for all students.”(Female, 2nd Baccalaureate)

The third most common value across the TFMs is heritage education, with a balanced distribution across genders (%FA men: 16.67%; women: 18%). Its presence is tied to a clear pedagogical objective: to connect students with their historical and cultural identity through the use of tangible and intangible elements from the past.

Heritage education is justified not only as curricular content, but also as a tool for the development of critical thinking, historical awareness, and community identity. This is clearly articulated in the narratives:

“Valuing documentary heritage as a source of knowledge for contemporary history and collective memory.”(Male, 4th ESO)

It is also directly connected to cultural sustainability and respect for collective memory, as one female teacher states:

“Historical memory and the appreciation of cultural processes are addressed through the analysis of maps, archives, and historical sources.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

Many proposals include educational field trips, work with primary sources, archive digitization, and active engagement through museum visits:

“The visit to the Prado Museum offers a unique opportunity to connect directly with cultural heritage.”(Male, 2nd Baccalaureate)

“The classroom becomes a musealized space that reclaims local history.”(Male, 1st ESO)

These practices reflect an understanding of heritage as a living pedagogical resource, enabling students to reflect on the present through the lens of the past while also fostering the protection, dissemination, and reinterpretation of cultural legacy.

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) emerges as a cross-cutting approach increasingly integrated into the proposals, reflecting the commitment of future teachers to educate for critical, engaged, and environmentally responsible citizenship. Although not as dominant as other values, its presence is notable and consistent across genders (FA% men: 10.90%; women: 10%).

Narratives show that this focus goes beyond environmental concerns and incorporates cultural, social, and educational sustainability aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda:

“Students will develop environmental awareness and reflect on the human impact on natural ecosystems.”(Male, 2nd ESO)

“The curriculum includes content linked to the SDGs, such as the consequences of war, wealth distribution, or environmental issues.”(Female, 4th ESO)

Moreover, connections are made between heritage, civic engagement, and sustainability, positioning education as a driver for eco-social transformation:

“The project aligns with the SDGs by promoting critical citizenship, social justice, and democratic participation.”(Male, 4th ESO)

“A critical and socially engaged attitude is fostered through activities conducted in real physical and urban spaces.”(Female, 3rd ESO)

Thus, this value becomes a lever for connecting the classroom with the world, as it integrates humanistic, scientific, and civic content from an eco-social perspective.

Peace education and coexistence has a lower presence in both male and female-authored TFMs (male: 10.26%; female: 7%). It is generally addressed through themes of mutual respect, collaborative work, and critical thinking. Frequent references are made to cooperative dynamics and values education:

“The class group is managed through dialogue, mutual respect, and emotional self-regulation.”(Male, 1st ESO)

A similar trend is observed in intercultural education, with higher representation in TFMs authored by women (men: 6.41%; women: 14%). This approach aims to acknowledge the cultural diversity of students and promote respect, empathy, and dialogue:

“The cultural plurality in classrooms has become very visible… visual language helps overcome barriers such as language differences.”(Female, 4th ESO)

Peace education and historical memory also appear more frequently in female-authored TFMs (men: 4.49%; women: 8%) and are deeply tied to the critical analysis of contemporary history and human rights education. Memory is addressed as a tool for justice and historical reflection:

“Students work with family testimonies, historical documents, and debates on the 1977 Amnesty Law.”(Male, 4th ESO)

We conclude with the value of gender visibility, which is significantly more prevalent in TFMs authored by women (men: 3.21%; women: 8%). These proposals aim to reintegrate women into historical narratives and develop a gender-sensitive perspective in the teaching of art, history, and citizenship:

“The curriculum includes basic knowledge about historically invisible groups: women, slaves, and foreigners.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

“The study of the Second Spanish Republic incorporates a gender perspective into the history of art.”(Female, 2nd Baccalaureate)

3.2.2. Analysis by Educational Level

To determine whether there was a significant relationship between educational levels and the type of educational value prioritized in the teaching proposals, a Chi-square test of independence was applied. The global analysis revealed a statistically marginal association between the two variables (χ2 = 47.71; df = 35; p = 0.071), suggesting that the use of educational values is not entirely homogeneous across different levels of education. Although the p-value is slightly above the conventional threshold of statistical significance (p = 0.05), its proximity justifies a more detailed examination.

For this reason, individual Chi-square tests were carried out for each of the educational values in order to assess whether their distribution varied significantly between the ESO and Baccalaureate levels. The results of these specific tests indicated that none of the educational values showed statistically significant differences in their usage across educational levels (all p-values were greater than 0.05). However, certain approaches—such as inclusion (χ2 = 7.84; p = 0.164) and interdisciplinarity (χ2 = 6.71; p = 0.243)—did exhibit some variability in distribution, although not to a statistically significant extent.

In this case, a Pearson correlation was not applied, as this test requires continuous, linearly related quantitative variables. The data under analysis consisted of absolute frequencies distributed across qualitative categories (educational levels and value types), for which the Chi-square test is a more appropriate method for evaluating the presence of dependence or independence between variables.

To facilitate a clearer understanding of the data, Table 7 displays the distribution of educational values across the four levels of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), while Table 8 focuses specifically on the two levels of Baccalaureate. This separation allows for a more precise interpretation of patterns and differences in the use of both values and methodologies between the lower and upper secondary education stages.

Table 7.

Distribution of educational values by level—compulsory secondary education (ESO).

Table 8.

Distribution of teaching methodologies by level—baccalaureate (first and second year).

The qualitative analysis of educational values reveals how certain ethical and pedagogical priorities are expressed differently depending on the educational level, offering insights into the kind of citizenship and critical awareness that future teachers aim to foster. Inclusion, the most frequent and cross-cutting value, is particularly notable in the third ESO (22.73%) and second Baccalaureate (21.62%). Across the different levels, this value is interpreted through an adaptive and universal lens. In the early stages of secondary education, the emphasis is placed on designing accessible and participatory learning environments, as reflected in the following narrative:

“Cooperative work is presented as an inclusive and cohesive tool that enhances participation for all students.”(Male, 1st ESO)

In Baccalaureate, the discourse becomes more structured and argument-driven, as noted by one female teacher:

“Strategies are applied to support and enhance the skills of all students, especially those with specific educational support needs (ACNEAE).”(Female, 2nd Baccalaureate)

Interdisciplinarity also stands out as one of the most representative values, with notable peaks in the first and third ESO (23.08% and 22.73%) and second Baccalaureate (21.62%). Narratives link it closely with active methodologies and integrative projects. One example illustrates this approach:

“The proposal combines history, ICT, oral expression, critical thinking, and civic competencies through activities such as debates, presentations, and textual analysis.”(Male, 2nd ESO)

In the fourth ESO, a female teacher highlights its use to foster critical citizenship:

“Related subjects within the Social Sciences can be taught in an interdisciplinary way… shaping students into citizens with civic reasoning and ethical awareness.”(Female, 4th ESO)

Heritage education, with a consistent presence across all levels (e.g., 23.08% in the first ESO and 18.92% in the second Baccalaureate), reflects a growing concern with historical legacy and its pedagogical application. The proposals range from tangible to symbolic heritage. As one male teacher states:

“The project focuses on the Roman heritage of El Bierzo, especially Las Médulas, as a teaching tool.”(Male, 1st ESO)

In the upper educational stages, female teachers introduce a more critical and museographic interpretation of heritage, as illustrated by the following narrative:

“The Prado Museum and the Reina Sofía are used as critical sources to analyze the presence (or absence) of women artists in their collections.”(Female, 2nd Baccalaureate)

Peace education and coexistence, with notable frequencies in the third ESO (18.18%) and first ESO (10.26%), is frequently associated with cooperative learning dynamics and the peaceful resolution of conflicts. One male teacher summarizes the approach as follows:

“The aim is to strengthen mutual respect, dialogue, and peaceful conflict resolution within the classroom.”(Male, 3rd ESO)

In contrast, education for historical memory, though less common overall, presents a more intense and critical narrative in the Baccalaureate and fourth ESO. For instance:

“Students will study crimes against humanity during World War II, political repression, and human rights.”(Female, 4th ESO)

Finally, values such as intercultural education—especially present in the fourth ESO (12.70%)—and gender visibility, although lower in quantitative terms, include narratives that are clearly sensitive to diversity and gender perspectives. One female teacher affirms:

“The history of Malinche and her pivotal role in the conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan is recovered, presenting her as a central figure in the historical narrative.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

3.3. Category 3: Assessment Instruments Used

3.3.1. Analysis by Gender

To determine whether there is a significant relationship between gender (male and female) and the use of different assessment methods in educational contexts, a Chi-square test of independence was conducted. The overall Chi-square test yielded a value of χ2 = 33.98 with a p-value of 0.0012. Since the p-value is less than 0.05, we can conclude that there is a statistically significant association between gender and the use of assessment methods as a whole, indicating that the distribution of assessment methods varies between male and female authors.

Subsequently, individual Chi-square tests were performed for each assessment method to identify whether any specific method showed significant differences in usage by gender. However, none of the individual methods produced a p-value below 0.05, suggesting that no single method is significantly associated with gender when analyzed in isolation.

This finding implies that although the overall distribution of assessment methods differs significantly by gender, no specific method on its own accounts for this difference in a statistically significant way. This could be due to the dilution of the overall effect when broken down by individual methods or to insufficient sample sizes for detecting statistically significant differences at the method-specific level.

Given that the general analysis indicated a significant association, a post hoc analysis was conducted to identify potential combinations of methods that might collectively be associated with gender. The post hoc results support the interpretation that, while there is a general trend of association between gender and the use of assessment methods, this trend is not strong or consistent enough to reach statistical significance at the level of individual methods.

These findings suggest the need for further studies with larger samples or the inclusion of additional contextual variables that may influence preferences for certain types of assessment tools, as illustrated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Distribution of Assessment Instruments.

To better understand this relationship, a qualitative analysis was conducted using narratives from the Master’s Theses (TFMs), which revealed meaningful differences in the perspective and application of assessment methods according to the teacher’s gender.

Oral expression is among the most frequently used assessment methods, especially among female authors (28.46%) compared with male authors (8.38%). The narratives show that female teachers tend to use this method primarily to foster critical thinking and argumentation, particularly through debates and presentations:

“During the sessions, especially through debates and presentations, oral interaction is used to assess students’ understanding and critical thinking.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

In contrast, male teachers more often apply oral expression as a means to present final results or summarize conclusions, reflecting a more expository rather than dialogic approach:

“At the end of the module, students present their conclusions through oral projects that integrate what they have learned in the practical sessions.”(Male, 1st ESO)

Gamified assessment is slightly more prevalent among male teachers (17.41%) than female (11.67%). The qualitative data suggest that men tend to favor digital tools such as Kahoot! or escape rooms to introduce competitive or playful dynamics:

“In Sessions 1 and 2, Kahoot! is used as a gamified tool to review and assess knowledge acquired about Greco-Roman culture.”(Male, 1st ESO)

Female teachers also employ gamification, but tend to integrate it into post-activity reflection, suggesting a more pedagogically grounded use:

“During the third session, an interactive breakout activity in Genially is used, with differentiated gamified tasks for Castilians and Aragonese.”(Female, 2nd ESO)

Student productions are a relatively evenly distributed method (11.61% for men, 13.86% for women). However, qualitatively, male teachers tend to focus on visual organization and information structuring, such as timelines or infographics:

“Students create global timelines to understand the evolution of life and the universe, connecting disciplines such as history, biology, and geology.”(Male, 1st ESO)

3.3.2. Analysis by Educational Level

To assess whether there were significant differences in the distribution of cases between the educational levels of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO) (first, second, third, and fourth year) and Baccalaureate (first and second year), a Chi-square test of independence was performed by grouping the levels into two categories: ESO and Baccalaureate.

The test yielded a Chi-square value of 6.25 with a p-value of 0.9366. Since the p-value is greater than the conventional significance threshold (0.05), the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. This indicates that there are no statistically significant differences in the distribution of cases between ESO and Baccalaureate levels.

From a practical perspective, this result suggests that the number of observed cases across both educational stages is statistically similar, indicating no marked bias in the distribution of data by educational level.

To further explore differences among educational levels, additional statistical analyses were performed. First, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine whether there were significant differences in the number of cases recorded per level. The analysis produced an F-statistic of 4.30 with a p-value of 0.0017, indicating that at least one educational level exhibits a significantly different frequency compared with the others. This suggests that the distribution of cases is not uniform across all levels considered.

Additionally, a Spearman’s rank–order correlation was applied to test for a potential trend in the number of records from the first year of ESO to the second year of Baccalaureate. The resulting coefficient was −0.49, with a p-value of 0.3287, showing that there is no statistically significant trend across levels. This implies that the number of cases does not follow a clearly increasing or decreasing pattern based on the educational level.

To facilitate a clearer understanding of the data, Table 10 displays the distribution of assessment instruments across the four levels of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), while Table 11 focuses specifically on the two levels of Baccalaureate. This separation allows for a more precise interpretation of patterns and differences in the use of assessment strategies between lower and upper secondary education stages.

Table 10.

Use of assessment instruments by educational level—ESO (first to fourth year).

Table 11.

Use of assessment instruments by educational level—baccalaureate (first and second year).

Although the quantitative analysis indicates that there are no statistically significant differences when comparing broader educational stages (ESO vs. Baccalaureate), the qualitative analysis reveals certain trends in the progression of the complexity of assessment instruments as students advance in their academic journey.

In the early years of ESO (first and second), low- and medium-complexity instruments are predominant, particularly those related to experiential assessment, practical activities, and gamification. These tools are designed to promote active participation and classroom engagement:

“Students participate in a simulated archaeological excavation using specific kits, applying real techniques in a controlled educational environment.”(Male, 1st ESO)

“A historical trivia quiz using Kahoot has been designed to review content in a fun and engaging way.”(Male, 2nd ESO)

This trend suggests that, in the initial stages, the pedagogical focus is on motivation and hands-on learning using methods that stimulate interest and direct experimentation. The presence of high-complexity instruments in the first ESO (46.43%) decreases in the second ESO (34.57%), highlighting a more playful and practical emphasis in the latter.

As students progress through the third and fourth ESO, assessment instruments evolve toward greater critical reflection and information synthesis. There is an increase in medium-complexity instruments, especially in the fourth ESO (47.06%), where oral expression and the creation of educational materials become more prominent:

“Students create global timelines to understand the evolution of life and the universe, connecting disciplines such as history, biology, and geology.”(Female, 4th ESO)

This shift reflects a transition toward methodologies that require knowledge organization and interdisciplinary thinking.

In Baccalaureate (first and second years), the use of assessment instruments becomes more complex, oriented toward critical reflection, argumentative analysis, and written production. Medium- and high-complexity tools predominate, aligning with the analytical and in-depth focus characteristic of this stage:

“Students write critical commentaries on artworks, relating them to historical and aesthetic movements.”(Female, 2nd Baccalaureate)

“Each student writes a reflective essay on the historical impact of 20th-century social movements.”(Male, 1st Baccalaureate)

Critical analysis and argumentative writing are central components of assessment in Baccalaureate, where students are expected to develop a deep understanding of historical and social phenomena.

4. Discussion

The results of this study reveal consistent patterns in the development of Master’s Theses (TFMs) by students in the Master’s Degree in Secondary Education Teaching, specializing in Geography and History. Although no statistically significant quantitative differences were observed between genders, the qualitative analysis reveals differentiated trends in the pedagogical intent behind the selection and implementation of methodologies, values, and assessment tools.

In line with studies such as a forthcoming publication by Universidad Isabel I, which analyzes more than 2000 TFMs, active methodologies (T4) are shown to predominate, especially in proposals presented by women. These are characterized by a more reflective use of tools such as gamification or oral expression, aimed at developing critical thinking and argumentation. Although focused on the STEM field, the study by Beroíza-Valenzuela and Salas-Guzmán [31] provides a useful explanatory framework to understand this trend. The authors emphasize that factors such as gender stereotypes, self-efficacy, and personal expectations influence how women position themselves in educational contexts, affecting their pedagogical choices. Appropriately contextualized, this perspective helps to interpret similar differences in the field of social sciences.

Although the primary focus of this study is empirical and quantitative, the analysis incorporates gender as a key category for exploring potential pedagogical differences. In light of the absence of statistically significant differences, it is essential to consider contemporary theoretical frameworks that conceptualize gender not as a fixed or essential condition, but as a socially and relationally constructed identity [20,32]. From this perspective, the results may reflect a shared pedagogical culture shaped by the structure of initial teacher training. Warin and Gannerud [20] point out that values traditionally associated with femininity in education—such as empathy, care, and cooperation—are increasingly adopted by teachers of all genders, especially in inclusive and reflective training environments. In line with this, Greco [22] emphasizes that gender is socially constructed from early childhood through everyday interactions, assigned roles, and social expectations. Therefore, the convergence in methodological choices observed in the TFMs should not be interpreted as gender neutrality, but rather, as evidence of a reconfiguration of contemporary teaching identities that transcend traditional binary stereotypes.

The lack of statistically significant gender-based differences in our findings does not imply gender neutrality in pedagogical design. As Savigny [33] argues, cultural sexism in academia often operates subtly, reinforcing gendered hierarchies even in seemingly egalitarian environments. These dynamics can influence how pedagogical approaches and academic contributions are perceived and valued, particularly when they align with care-oriented or inclusive practices typically associated with femininity. Similarly, Mason [34] points out that the presumption of neutrality often conceals deeply rooted gendered expectations, especially in how teaching competencies and authority are evaluated. As Vanner et al. [23] demonstrate, gendered dynamics in education frequently operate beneath the surface, subtly shaping perceptions of teaching strategies without necessarily producing explicit divergence in formal choices. This interpretation resonates with Russell’s [35] call to move beyond binary gender frameworks and recognize how fluid and intersectional identities influence pedagogical practice. From this perspective, the observed convergence in methodological choices may reflect a shared pedagogical culture shaped by evolving gender norms rather than an actual absence of gender-based effects.

However, a closer qualitative reading suggests that subtle patterns persist beneath this apparent convergence. For instance, male students tend to apply approaches such as experiential learning or gamification from a more expository or review-oriented perspective. This may reflect prior cultural and academic influences, as also suggested by Guevara [36], and reinforces the idea that gender continues to shape pedagogical preferences, even in nuanced or implicit ways.

In terms of assessment, a significant evolution can be observed compared with studies from a decade ago. Monteagudo, Molina Puche, and Miralles [37] warned of the overwhelming predominance of memorization-focused written exams—scarcely incorporating rubrics, cooperative tasks, or portfolios—while Gómez Carrasco and Miralles [38] showed that Geography and History assessments in lower secondary education rarely included historical thinking, instead favoring closed, factual-recall questions. Furthermore, the qualitative study by Alfageme-González, Monteagudo, and Miralles [39] revealed a generational divide in assessment conceptions: more experienced teachers tended to retain traditional evaluative models, while younger teachers showed greater openness to formative approaches.

While these studies do not offer a definitive picture of the current state of assessment practices in Spanish classrooms, the results of the present study suggest positive signs of transformation in how assessment is conceived and applied in initial teacher education. The inclusion of co-evaluation rubrics, reflective journals, and open-ended tasks in the analyzed TFMs suggests a shift toward more competency-based models including the development of critical thinking, source interpretation, and disciplinary argumentation. This aligns with the findings of Tirado-Olivares et al. [40], who demonstrated that the integration of active learning methodologies combined with formative assessment technologies enhances not only academic performance but also pedagogical awareness among pre-service teachers in the social sciences. In this sense, the training system shows promising signs of progress toward more competence-oriented models, although, as these authors also highlight, perceived competence does not always translate into actual mastery, underscoring the importance of integrating reflection and continuous monitoring mechanisms in assessment practices.

With regard to educational values, the TFMs reflect a strong commitment to inclusion, interdisciplinarity, and heritage education, particularly in upper secondary levels such as Baccalaureate. At these stages, more critical dimensions such as historical memory and gender visibility also emerge, reinforcing the role of the TFM as a space for ethical reflection and pedagogical transformation [6].

In terms of educational level, a progression in methodological complexity is evident: in lower secondary education (ESO), experiential proposals (e.g., dramatizations and games) are more common, while in Baccalaureate, methodologies requiring greater abstraction (e.g., essays, critical commentaries) prevail. This progression is consistent with findings by Pagés et al. [7], who interpret it as an indicator of pedagogical maturity. Although focused on mathematics education, Martín-Cudero et al. [41] highlight that active methodologies linked to the STEAM approach foster critical thinking, creativity, and the social contextualization of learning. These are also key competencies in History and Geography education, justifying the methodological analogy observed in the analyzed TFMs.

Finally, the study raises questions about the extent to which methodological choices are influenced by students’ prior disciplinary training, as suggested by Fernández et al. [42] and Mosquera and Santamaría [43]. Along these lines, García-Lázaro et al. [44], although not focused on a specific area, underscore the need to integrate technological, pedagogical, and disciplinary knowledge (TPACK model) in initial teacher education. The authors also warn that a high perceived self-efficacy in the use of ICT does not necessarily imply real competence, particularly in school environments where traditional models of technology use prevail. This warning is especially relevant in the social sciences, where the transformative potential of technology remains underutilized.

Taken together, the findings highlight the value of the TFM not only as an academic product but as a formative space where methodological innovation, critical reflection, and ethical commitment to teaching intersect. This study underscores the need for further research into how gender, disciplinary background, and educational level interact in shaping teacher identity in hybrid and digital environments. While this study is based on a single university, it is important to note that this institution has national reach, enrolling students from all across Spain. This contributes to a certain degree of socio-territorial diversity within the sample. Nevertheless, the fact that the data comes from a single institution and covers only one academic year is acknowledged as a limitation. Therefore, we propose expanding the analysis in future research to include TFMs from multiple academic years and other universities. This would allow for the development of longitudinal studies and enhance the generalizability and comparative value of the findings.

5. Conclusions

This article reviews a corpus of 54 Master’s Theses (TFMs) from the Master’s in Teacher Training in the specialization of Geography and History presented at the International University Isabel I (Spain). Of the 54 theses, 32 were written by men and 22 by women, representing 59.26% and 40.74% of the sample, respectively. Regarding the educational level targeted by the teaching proposals, the sample includes 9 TFMs for first-year ESO, 16 for second-year ESO, 4 for third-year ESO, 15 for fourth-year ESO, 2 for first-year Baccalaureate, and 8 for second-year Baccalaureate.

Category 1: Teaching Methodologies

Regarding teaching methodologies, no statistically significant differences were found by gender (H1). However, the qualitative analysis revealed distinctions in the pedagogical intent of the future teachers. Female authors were more likely to use strategies such as flipped classroom and gamification, typically with reflective and participatory aims. In contrast, male authors tended to favor experiential learning, often with a more expository approach. These differences can be interpreted through the lens of gender as a social construct, recognizing that methodological decisions are not neutral, but are shaped by differentiated educational trajectories and socially internalized expectations about the teaching role.

With respect to educational level (H2), a clear methodological progression was observed, aligned with students’ cognitive development. In the lower years of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), motivational and practical strategies prevailed, including gamification, inquiry-based learning, and collaborative activities. In upper secondary levels, particularly in Baccalaureate, more cognitively demanding and analytical methods became more frequent, such as project-based learning, argumentative writing, and structured debate.

It is important to note that this evolution does not stem from regulatory mandates, as educational policy does not prescribe specific methodologies for each grade level. Rather, it provides a general framework oriented toward competency development. As a result, the methodological choices found in the analyzed Master’s Theses (TFMs) are not based on externally imposed patterns, but on autonomous decisions made by the teacher education students. These decisions reflect both their interpretation of the curriculum and their personal views on effective teaching strategies. Consequently, this methodological progression may be interpreted as a sign of didactic awareness among future teachers: the greater the complexity of the content and intended competencies, the greater the degree of pedagogical reflection observed in instructional design.

Moreover, these methodological decisions not only shape the teaching plan but likely influence how students perceive and engage with the learning process. The methodologies applied serve as mediators between knowledge and educational experience, affecting student motivation, levels of participation, and the development of key skills. Thus, analyzing the methodological choices in TFMs allows for insights not only into the construction of professional teacher identity but also into the types of educational experiences that these future educators may foster in their classrooms.

Category 2: Educational Values

Regarding the educational values promoted in the Master’s Theses (TFMs), no statistically significant differences were found based on the authors’ gender (H5). However, the narrative analysis revealed meaningful nuances in the pedagogical intentionality of the future teachers. Both male and female authors prominently prioritized interdisciplinarity and inclusion, indicating a shared commitment to overcoming curricular fragmentation and addressing classroom diversity through flexible and integrative strategies.

Heritage education also holds a significant presence in the TFMs written by both genders, although with different emphases. Male authors tend to highlight the historical and documentary value of heritage, focusing on its usefulness as a source of knowledge about the past. Female authors, on the other hand, are more likely to integrate heritage into pedagogical proposals connected to social awareness, historical memory, and critical thinking. In these cases, heritage is employed as a means to problematize the dominant historical narratives, give visibility to marginalized identities, and foster civic reflection, particularly in higher educational levels.

Values such as Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), peace education, and intercultural education, though less frequent quantitatively, reflect an emerging commitment to fostering critical and socially engaged citizenship. Female authors, in particular, tend to incorporate these dimensions with greater narrative depth, embedding references to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), cultural diversity, and the peaceful management of conflict. Although these patterns do not reach statistical significance, they suggest differentiated narrative approaches and ethical sensibilities.

With regard to gender visibility, a clear qualitative difference emerges: although this value represents a smaller portion of the overall sample, it appears more frequently and with greater elaboration in TFMs authored by women. These proposals include explicit references to the representation of women in history, critiques of hegemonic narratives, and the application of feminist perspectives in curriculum design and instruction.

As for differences by educational level (H6), a progression is observed in how values are addressed. In the lower levels of Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO), values tend to be incorporated through functional or instrumental approaches such as cooperative learning or inclusive dynamics. In Baccalaureate, however, values are approached in a more critical, reflective, and argumentative manner. This shift not only reflects students’ cognitive development but also indicates a deeper level of pedagogical awareness in the planning of instruction. Given that current educational legislation does not mandate specific values, the choices reflected in the TFMs are the result of autonomous decisions made by pre-service teachers.

Lastly, it is important to note that the integration of values into Geography and History is not explicitly prescribed in the official curriculum. Rather, it depends on how future teachers interpret and reconstruct these disciplines from a personal and pedagogical standpoint. In this regard, the TFMs offer a valuable space to explore how prospective educators build their professional identities through ethical and socially responsive educational commitments.

Category 3: Assessment Instruments