1. Overview of the Problem

Mid-career faculty (MCF) are the largest faculty cohort group in higher education and include faculty who are post tenure. Kenyon [

1] defined the time period as between 2 to 12 years post-tenure, whereas Baldwin et al. [

2] defined mid-career as the period of time after a faculty member has earned tenure and before they start to prepare for retirement. These faculty members most often are at the rank of associate professor and have successfully navigated their early career in academia. Importantly, as pre-tenure faculty members, they may have received significant support to reach that point; this support may have included mentorship from a senior faculty member or committee, focused professional development on teaching in post-secondary education, and ‘start up funds’ to launch the early career faculty members into their research trajectory [

2]. Additionally, as a pre-tenure member, they were expected to devote little time to service commitments so that they could concentrate on their teaching and research portfolios. This support contrasts with the experience of post-tenured faculty who now are expected to serve on committees, supervise more students, teach without supports, and be successful with submitting grant applications, conducting research, and publishing [

3,

4]. Kenyon [

1] characterized these pressures as the “associate grind”. Importantly, the expectations may vary among institutions and among disciplines, so MCF need to also be aware of the particular standards for their own discipline and how they are informed by institutional context. For example, research-intensive universities will have different standards than undergraduate-focused universities; furthermore, faculty in science- or health-focused disciplines will have different expectations than faculty in performing arts, education, and psychology. These contextual differences mean that the faculty members moving toward promotion need to be very aware of the impact of disciplines on tenure and promotion standards from the beginning of their faculty journey.

Not only is the ‘grind’ exhausting, but it also may have a negative effect on efforts to move towards promotion to full professorship. If an individual is considering advancing to full professor, it is crucial for them to strategize how to manage their responsibilities effectively. Associate professors must aim to meet certain criteria, which might seem ambiguous at times, including achieving recognized authorship, publishing in high-quality journals, securing successful grant funding, and delivering strong teaching performance [

5]. Additionally, these faculty are expected to be good citizens of the department or college, and rather than merely participating in committees, they are likely to be invited to chair these committees and assume a leadership role. In other words, the accountabilities remain the same, but the faculty member now needs to reach a higher bar that is often only vaguely described in the standards for promotion.

The purpose of this reflective article is to briefly identify the challenges encountered by mid-career faculty and to examine the literature regarding the role that mentorship and professional development could play in helping MCF achieve promotion. Furthermore, we will explore how these strategies can work towards faculty engagement during a phase in their careers where MCF are frustrated and yet receive very little guidance in meeting their goals and aspirations [

6]. Ensuring MCF are remaining focused and engaged has enormous personal benefits but also contributes to institutional (university and college level) benefits. Engaged faculty will more likely be retained, ensuring there are mentors for junior faculty in that department and college. Furthermore, they can lead research projects that are larger in scope, using their networks and research expertise. Lastly, engaged faculty will be more likely to engage students in their classes and ensure better outcomes for students. Moreover, this positive cycle will promote better research and teaching, translating into better outcomes for community and society writ broadly.

2. Challenges of Mid-Career Faculty

Despite their importance as essential members of the academy [

7], the challenges faced by MCF have often been overlooked, under-researched, and ignored [

8]. Baker [

9], Grant-Vallone and Ensher [

3], as well as Weimer [

10], have drawn attention to this critical issue. The frustration experienced by MCF, as identified by Baldwin et al. [

2] and Karraa and McCaslin [

11], can have a significant impact on their job satisfaction and overall commitment to the institution. Interestingly, associate professors are sometimes described as the some of the unhappiest people in the academy [

6,

12]. Similarly, Romano et al. [

4] described MCF as the most productive group of faculty members but the most dissatisfied.

Mid-career faculty are expected to continue to be productive in research and teaching, but, at the same time, they are expected to take on additional duties regarding service, leadership and student supervision and research outputs; expectations for each of these categories of faculty responsibility vary among disciplines and [

3]. According to Welch et al. [

5], institutions are sending out mixed messages by encouraging faculty to serve on committees at the university level, including faculty governance committees, but offering little incentive or reward for that service, even during the promotion process. In Heffernan and Heffernan’s [

13] study, over a third of MCF felt that they were not supported at all by their college or institution, and they were entirely responsible for their own career development.

Schmiedehaus et al. [

14], posited that neoliberalist notions that have spread to the university shifts the environment from one of exchange and collaboration to individualism, competition, and siloed work. Rewards for collaboration are supplanted by rewards for individual achievements. Moreover, MCF must determine teaching, research, and service goals within a quickly changing environment, especially through the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Shifting institutional goals, changing student demographics, new learning technologies, and now artificial intelligence are contextual factors to which all faculty must respond [

14]. Similarly, MCF need to adapt to the changing environment after initial successes and chart their own path forward (that potentially may be decades long), even though the targets are ill-defined, and there are no dedicated additional resources specific to MCF needs.

3. The Challenge of Promotion to Full Professor

Many of the issues encountered by MCF are further demonstrated in the pursuit of promotion to full professor. As noted by Bowering and Reed [

15], academia is very competitive, and there is intense performativity pressure even though “promotion targets are neither transparent nor well-operationalized, that variations exist in the processes within and across university departments and faculties and that the decision makers can lack adequate training” (p. 2). Faculty members are unable to accurately assess their progress and improve their performance if the targets are vague and are open to interpretation [

8,

15]. The standards for promotion to the rank of full professor focus on research productivity, even though associate professors are under pressure to take on more teaching, supervision, and especially service, impacting their capacity to conduct research [

15,

16]. This focus on research productivity aligns mostly with research-intensive universities, and expectations regarding teaching, supervision, and service will be informed by disciplinary standards. Additionally, some faculty members may focus more on teaching and service, and Kenyon [

1] described these faculty as “highly respected contributors within their institutions and beyond–influential and deeply appreciated colleagues who make a lasting impression on a university, on a discipline, and in countless students’ lives” (para. 13). These contributions, unfortunately, do not seem to weigh as heavily in promotion decisions [

16].

Bowering and Reed [

15] contended that work environment, role conflicts, and work–life balance contributed to difficulties with career progression. The faculty members in their study “described a work environment where the expectations were unclear, little time to meet research obligations was afforded, bullying and incivility occurred, and grantsmanship and publication were difficult” [

15] (p. 14). Many associate professors, especially women, were not sure they wanted to pursue promotion to full professor, and Buch et al. [

16] noted that it seemed as if “women were standing still at associate professor” (p. 39). Buch et al. [

16] identified barriers to promotion including:

Lack of attention to career planning by associates;

Lack of institutional and departmental attention to and support for career development needs of associates;

Lack of career development opportunities for associates;

Disproportionate service demands/administrative duties for associates that interfere with progress toward full professorship;

Lack of transparency and clarity regarding promotion criteria;

Need for more flexible and inclusive “paths to professor” that recognize a broader range of contributions. (p. 40)

Herein lies the challenge and why further discussion and investigation is required to ensure that campuses can determine how to implement mentoring programs that may lead to better and more supportive processes for MCF in achieving their career goals.

4. Women in the Academy

The problem seems to be most acute for women, even though the demographic profile of full-time academics has been shifting slowly. As Canadian faculty members, we are most aware of the Canadian context; the following information about women faculty is presented from our geographical and political lens. According to Statistics Canada data from 2021/2022, although many more women have been joining academia over the last two decades, they are underrepresented in the full professor category [

17]. Women attained parity at the assistant professor rank in the early 1990s and now slightly outnumber men at that rank. The proportion of women associate professors is 44.3%. However, at the full professor rank, women comprise only 31.4% in 2021/2022 [

17]. Of the 42,204 full-time teaching staff, 17,535 were full professors in 2021/2022, 15,588 were associate professors, and 9081 were assistant professors. These numbers could be misleading though; in the last two decades, the number of full professors who are 65 or older has risen dramatically (especially for those 70 and older); those older full professors are predominantly men [

17].

Women faculty encounter many of the same barriers and challenges as their male counterparts. However, there are additional challenges that contribute to the disparity between the numbers of women and men full professors. For example, James et al. [

18] noted that career interruptions because of maternity leaves can have an adverse impact on women’s forward progress, especially in their research. Furthermore, there are continuing differences in gendered expectations regarding care and household duties and responsibilities [

8,

18]. The culture of universities perpetuates the unrealistic idea that family commitments should not impact the work life of a faculty member [

15]; this tension is felt predominantly by women faculty [

15,

18]. Moreover, these disparities were accentuated during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially during the periods of school and daycare closures [

18].

Other contributing factors include the lack of mentoring and networking afforded to women faculty; women are less likely to be connected to collegial networks. The result can be feelings of isolation and lack of support for research productivity [

8]. Moreover, in Terosky et al.’s [

8] study, women faculty identified that departmental colleagues were responsible “for their disproportionately high administrative and service workloads” (p. 65), as well as lack of mentoring and support in their academic journey. As mentioned previously, the realities of women faculty will vary by institution and discipline. Other factors such as being a visible minority, having mental health challenges, or expressing gender diversity can also have an impact on how others (faculty and students) respond to certain faculty members.

Specifically, studies have pointed to the amplified challenges that women faculty of color or Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) women experience including increased emotional labor, disparities in pay, negative and racist comments from students and colleagues, and structural inequities regarding tenure and promotion [

19,

20]. Women of color often feel pressured to serve on diversity task forces and anti-racism committees [

20]. Lin and Kennette [

20] advocated that tenure and promotion standards should be redesigned to develop a more “equitable review process” to take into account the invisible and emotional labor of BIPOC faculty and “address challenges related to teaching and scholarship that lead to discrepant outcomes compared to white faculty in order to amplify the contribution of women of color faculty” (p. 16). Kulp et al.’s [

21] extensive study on clarity of standards in tenure and promotion identified that women experienced lower promotion clarity and the intersection of being a woman and BIPOC is related to significantly lower promotion clarity (p. 89). Further, BIPOC women can experience particularly strong resistance when applying for full professor [

21]. As evidenced in these multiple studies, intersectional racism and sexism make the journey of BIPOC women faculty a multi-layered challenge [

19].

Clearly, the career path for MCF as they strive to achieve promotion to full professor can be difficult. There are many examples in the literature of how the lack of support for MCF has personal and professional impacts. The problem may be most acute for women in academia. This issue should receive more attention from post-secondary institutions as there is an institutional impact when mid-career faculty reach a plateau post-tenure and struggle to remain engaged [

6]. The following section outlines the impacts at the institutional level.

5. The Impact of Mid-Career Faculty Attrition

In the realm of higher education institutions, ensuring the retention of MCF plays a pivotal role in upholding institutional quality and fostering collective advancement. Regrettably, the challenges confronted by MCF often remain understudied and overlooked, potentially resulting in frustration and even attrition [

5,

6]. Baldwin and Chang [

7] highlighted a discernible gap in research attention, noting that MCF receive limited scrutiny compared to their early career counterparts. When MCF do not feel supported or engaged in their academic institutions, there is a higher likelihood that they will seek opportunities elsewhere, such as other higher education institutions, or they may leave academia all together [

13]. The attrition of MCF poses a considerable financial burden on institutions, involving costs associated with advertising, recruiting, orientating, and training new faculty. Studies by Baker [

9], Baldwin and Chang [

7], Campbell and O’Meara [

22], and Thompson [

23] highlighted the crucial role of educational leadership in facilitating faculty retention. Even though significant attention and resources are focused on pre-tenure faculty retention and success, the costs associated with MCF departures do not seem to be as seriously considered institutionally [

24].

Heffernan and Heffernan [

13] estimated that as early as 2023, a significant portion of current MCF in higher education may retire (25%) or leave the profession (25%). With the loss of MCF through retirement or attrition, there will be a loss of collective expertise in research, supervision, and teaching, as well as a reduction in the pool of potential department, college, and institutional leaders [

25]. While some succession planning is expected, sharp reductions in MCF numbers will deprive the institution of its institutional knowledge and historical perspective, which are instrumental in collective growth and continuity [

13]. Failure to implement effective faculty retention strategies can have serious consequences for higher education institutions. Heffernan and Heffernan [

13] highlight the potential departure of MCF if they do not receive the necessary support for their professional growth. Losing MCF not only results in the loss of experienced educators, but inattention to MCF retention can also have a severe impact on the depth of the leadership pool from which an institution can draw [

25].

These numbers also underscore the urgency of addressing MCF retention to mitigate the anticipated consequences. Failing to retain MCF can result in poor student outcomes, increased workload for remaining faculty, and faculty burnout [

4,

16]. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this trend; the “great resignation” resulting from individuals re-evaluating their career goals and quality of life because of the pandemic extended to higher education faculty considering resignation [

14].

Baldwin and Chang [

7] describe the critical role that MCF play on campuses and characterized them as “the keystone of the academic enterprise” (p. 28). They are essential players in instructional, program development, administration, and citizenship roles [

7]. Mid-career faculty also form a bridge between new assistant professors and full professors as they look towards retirement. Loss of MCF can negatively impact the collective expertise and cohesion of academic institutions, hindering the long-term vitality of the institution [

7].

6. Retaining MCF: A Strategic Imperative

Given the potentially costly repercussions of MCF turnover, it is crucial for educational leaders to prioritize retention strategies. Investing time, energy, and policy development in supporting MCF professional development and career growth are paramount [

3,

7,

26]. Further, MCF should be strongly encouraged to participate in these workshops or faculty mentorship programs; while pre-tenure faculty can have incentives such as a course release, MCF are rarely incentivized to participate in mentorship programs even when they are encouraged to demonstrate a commitment to improvement as part of their tenure and promotion applications [

26]. By offering opportunities for growth, mentorship, and recognition, institutions can create an environment that nurtures MCF and ensures their continued engagement and satisfaction. It is worth noting that MCF need not pursue all opportunities simultaneously but can instead focus on one or two areas at a time.

Focusing on the retention of MCF not only contributes to the strength and perseverance of academic institutions, but also allows for the continuity of institutional knowledge, fosters faculty agency, and promotes a vibrant intellectual community [

4]. Ultimately, these factors enhance student success by providing students with access to experienced educators who can facilitate their learning and development [

27].

As Terosky et al. [

8] contend, further research into how to mitigate these challenges is needed, and all levels of the institution can play a part in helping MCF stay invested in continuing along the career trajectory towards full professorship. One model, proposed by Baldwin and Chang in 2006, pointed to a possible solution in proposing a mid-career faculty development process. This model will be described in more detail in the following section. We will elaborate on two pieces of the model that we believe are especially critical areas for MCF retention and are areas that do not require a significant infusion of new resources to achieve.

7. Mid-Career Faculty Development Process

The mid-career faculty development model was created based on the work of Baldwin and Chang in 2006. Baldwin and Chang brought attention to the limited focus on the development of mid-career faculty (MCF), as institutional efforts predominantly centered around the professional growth of their early career counterparts. In their influential work on “keystone faculty”, Baldwin and Chang underscored the significance of acknowledging and addressing the needs of MCF. Conducting a comprehensive exploration, they revealed that programs and initiatives designed to support MCF are diverse and contingent upon institutional contexts. As a result of their research, they formulated the MCF development process, a framework designed to encapsulate the support mechanisms available for MCF as they navigate the pivotal middle years of their academic careers.

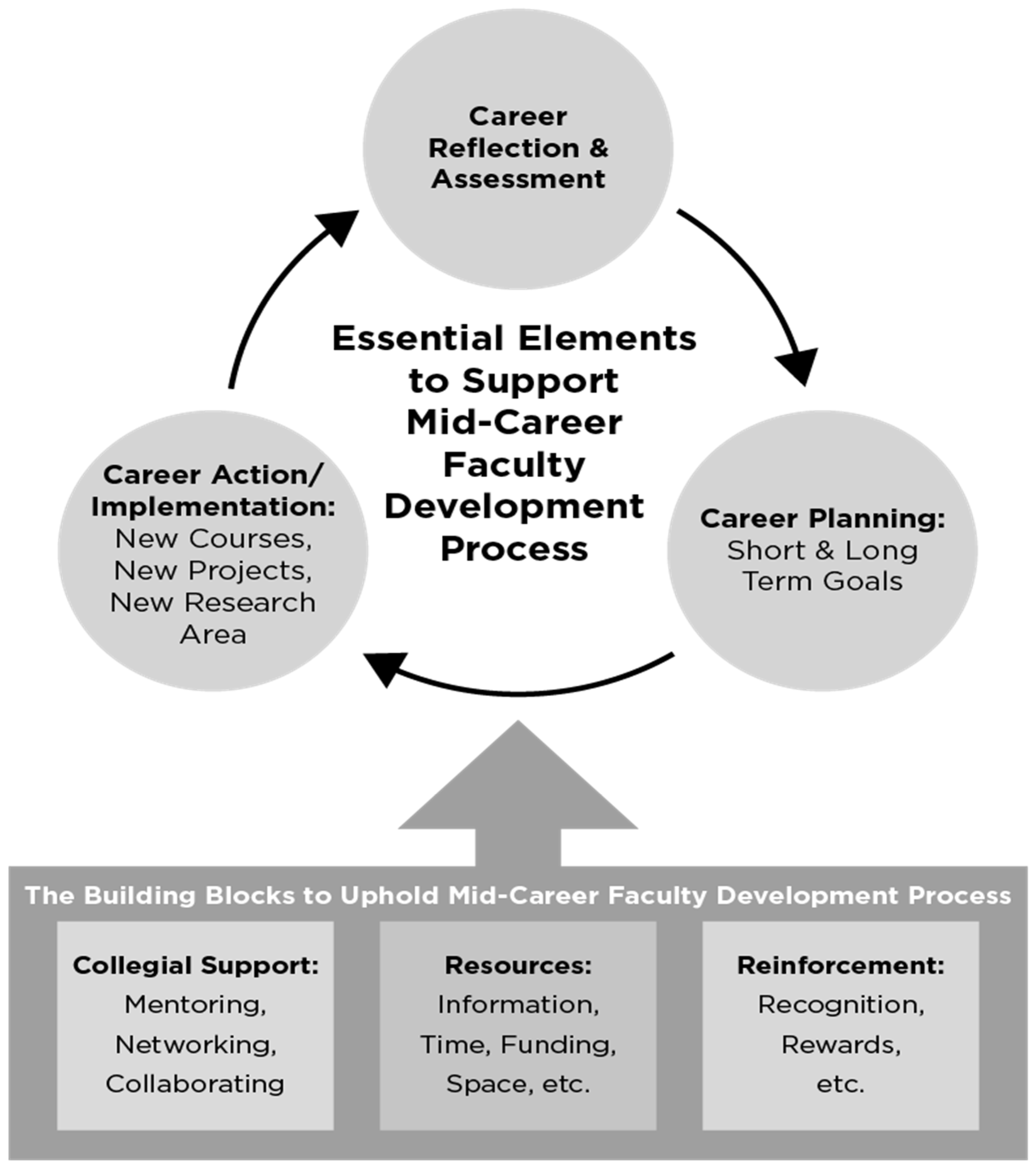

The authors of this model (

Figure 1) specifically designed it to serve as a guiding framework for deans, department chairs, and faculty development committees seeking to establish a support system for MCF within academic institutions. Since its original publication, the model has gained significant recognition in academic literature on MCF, with numerous studies referencing and building upon its principles [

2,

28,

29,

30].

This model has been crafted as a three-step approach to support MCF development, ensuring the necessary resources are available to sustain this process [

7,

29]. The steps include career reflection (informal and formal reflection and importance of reflection), career planning (short- and long-term goals, promotion after tenure), and career action and implementation (professional development and career advancement, scholarly teaching and scholarship). Baldwin and Chang’s [

7] work is foundational in understanding how to support MCF, and other researchers have explored the topic of MCF and largely agreed with Baldwin and Chang’s findings [

6,

24,

28]. As this process addresses many key topics pertinent to supporting MCF, we chose to focus on only one of the building blocks that uphold the MCF development process, collegial support, and one of the essential elements to support the MCF development process, career reflection and assessment. We chose to focus on this element, as in our own experience, these elements were of utmost importance in our academic journey. Furthermore, other authors such as Pastore [

28] agree that this area is an essential piece of Baldwin and Chang’s model.

7.1. Collegial Support

Faculty appreciate formal and informal support from colleagues. While mentoring programs are usually more formal, opportunities to meet informally are equally important in building collegial relationships and a sense of belonging [

5,

28]. The types of collegial support can come in the form of mentoring, networking, and collaborating; these types of support can be structured and formal or take a more informal approach. Further, collegial support can include guidance and advice related to all aspects of faculty workload, including research, teaching, and service. Notably, the type of support that they need or require may depend on the stage of their career; for example, MCF prefer asynchronous, digital supports that they can access when they can fit it into their schedules [

6]. Each of these forms of collegial support will be elaborated upon in the following sections.

7.2. Mentoring

Mentoring and professional development were the most impactful in terms of MCF’s feelings of being supported, which enhanced their intentions to stay [

13]. Focused mentorship programs should begin as soon as faculty are promoted to the associate professor rank. Buch et al. [

16] advocated for establishing a “comprehensive mid-career mentoring program that is responsive, inclusive, flexible and organic” (p. 44). Many researchers have pointed out the benefits of peer mentoring [

15]. These mentors, though, should be trained to ensure that their support is helpful and is focused on the specific needs for the rank; associate professors have expressed more dissatisfaction with their peer mentoring experience than assistant professors, highlighting the need for specific advice and support depending on rank [

15]. Mentors can be individuals who have already achieved a full professor status or a leader in higher education who understands the tenure and promotion process at their institution.

Furthermore, MCF need encouragement and mentorship regarding development of their career plans [

3,

16]. They should think about or reflect on their career goals, receive guidance and knowledgeable advice on the promotion criteria, conduct a self-assessment focusing on the next stages of their faculty career, discuss the plan with their mentor(s) and the department head or chair, and then work toward their goals; the reflection and planning are key elements for a strong plan that will set them up for aspirational yet realistic goals [

3,

16,

30]. This planning should begin as soon as they are promoted to associate professor 1 [

16,

31].

While formal mentoring between senior colleagues and associate professors is needed, there are also benefits to setting up self-selected mentorship exchanges and peer-to-peer mentoring [

8]. Faculty may feel more comfortable with self-selected mentors and will then be more likely to continue the mentorship relationship. Additionally, MCF will feel a sense of agency if they can approach their own mentors. Whether the mentors are peers, are self-selected mentors, or formal mentors, the mentors should receive some professional development on how to provide effective mentorship [

32].

7.3. Networking

Building networks of colleagues on campus and beyond promotes a sense of community and serves to expand possibilities for research and connection [

5]. These networks will be beneficial for career growth, including the opportunities to collaborate on research applications, research projects, and publications. The faculty members may appreciate opportunities to discuss research, but opportunities to discuss teaching and learning practices are also beneficial in expanding faculty members’ pedagogical skills and expertise [

4].

7.4. Collaborating

Collaboration can take many forms in faculty work. Several authors focus on peer mentoring that centers on women faculty supporting each other in working towards promotion to full professor [

8,

31,

33]. For example, Darling et al. [

31] discussed women faculty members’ individual needs as faculty and then described how to collaboratively work towards addressing these needs, including completing peer observations of each other’s teaching, providing letters of support, and collaborating where possible on research, publications, and presentations; Terosky et al. [

8] proposed similar measures. Importantly, the women faculty members found their meetings to be safe spaces where they could talk about their concerns, questions, challenges, and successes. This collaborative environment was crucial and effective; all members of the group achieved promotion within a short time frame. Of note, Darling et al. [

31] recommended that the collaborative group be interdisciplinary so that group members can contribute insights from different disciplinary perspectives; this finding aligns with the work of Rees and Shaw [

33].

7.5. Career Reflection and Assessment

Mid-career faculty have specific needs for their own personal and professional growth that require careful consideration and dedicated resources (financial and human) to promote continued engagement in their work while working towards achieving their career goals [

16]. There needs to be transparent, consistent, and fair criteria that can help associate professors identify the achievable and important milestones in their journey to achieve certain goals such as promotion to full professor rank [

16]. Engaging in reflection, setting career goals, and accessing personal and professional supports are critical in ensuring that MCF remain engaged in their work and more satisfied with their career path. Building on Baldwin and Chang’s [

7] work, it is recommended that faculty members actively partake in self-reflection concerning their career trajectories. This process should encompass a thorough evaluation of their professional strengths, weaknesses, and identified areas for ongoing development. This is also a necessary step in the promotion process. Reflection can include student evaluations, annual faculty reports, and post-tenure review processes, such as promotion from assistant to associate professor. In addition, Hamilton [

24] suggests that faculty can use reflection to improve their teaching practices. Reflection on teaching can be considered scholarly teaching, where faculty use systematically and strategically gathered evidence to develop themselves as effective teachers [

34].

To address the challenges faced by MCF and promote their retention, it is essential to prioritize professional development opportunities [

7,

13]. DeCourcey et al. [

35] emphasized that supporting MCF’s professional growth and agency is vital to their engagement and satisfaction within the institution. Professional development should encourage MCF to critically examine their teaching practices, foster faculty leadership, and facilitate conversations that enable a transition from scholarly teaching to the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) [

24,

36]. One of the challenges that college MCF face is maintaining vitality in teaching, including engagement with scholarly activities, such as SoTL ([

35]). The scholarship of teaching and learning is an international movement in higher education that contributes to the quality of teaching and learning research at the individual, faculty, program, and institutional level, as well as higher education in general [

37,

38,

39]. Accessing support from individuals (educational developers or instructional designers) within centers for teaching and learning can assist faculty to improve their teaching and learning “through literature-informed, rigorous methodological inquiry, and peer disseminated findings” [

39] (p. 2). Educational developers in higher education can support MCF development, both personal and professional, as professional development is essential for faculty to continue to grow as educators, leaders, and scholars [

40] According to Kanuka and Anuik [

6], opportunities to engage in collaboration and socializing with colleagues through networking and regular professional development activities result in a reduction in feelings of isolation and enhance relationships between employees and the institution.

8. Discussion

Throughout this paper, we have discussed some of the tensions and challenges faced by MCF in academia. We acknowledge these challenges may be both institutional and/or discipline-dependent; however, these challenges are real and can be a barrier to faculty reaching their full potential. The results from Heffernan and Heffernan’s [

13] study were alarming even at the time of publication. In this study, the authors predicted that upward of a half to two-thirds of faculty could leave the academy due to a variety of frustrations which we have addressed in this paper. Specifically, the authors predicted that current MCF in higher education would retire (25%) or otherwise leave the profession (25%). Key takeaways we highlight include tenure and promotion standards, women in the academy, and lack of support for professional development.

Hamilton [

24] noted that there is a financial burden that is associated with replacing departed MCF, including costs to advertise, recruit, orient, and support professional development of new faculty. There is also a human cost to having a lack of institutional support for MCF in tenure and promotion and career development. Decreased morale and loss of institutional knowledge and history can also impact MCF in both their career reflection and assessment. Educational leaders should dedicate their time, energy, and policy-making efforts towards supporting MCF in their professional development and career growth, addressing their unique [

7,

24]. The purpose of this paper is to shed light on some of the reasons why MCF may be leaving higher education. We hope this paper will spark conversations within academic institutions about the importance of acknowledging the experiences of MCF, so that context-specific solutions can be developed.

9. Conclusions

Mid-career faculty are essential members of academia. Because they have navigated through the processes to achieve tenure, they have demonstrated their skills in teaching and research. However, crossing the threshold into mid-career, they are expected to take on more extensive service commitments while continuing to develop their teaching expertise and research success. These tensions and increasing workloads may lead to frustration, disengagement, and potentially, burnout. The challenges are especially pronounced for women faculty. Post-secondary campuses need to invest energies into supporting the specific needs of MCF to ensure that they continue to be productive while protecting their wellbeing. A robust approach includes collegial support, resources and funding, reinforcement and recognition, and attention to structure and environment. Lastly, faculty themselves need to ensure that they are accessing the resources and supports available to them in order to stay engaged and stay well in their academic journey.

10. Limitations and Future Research

We acknowledge that this piece is reflective in nature and is based on our personal experiences as white, Western, female scholars in academia. The purpose of this paper is to shed light on some of the reasons why MCF are leaving higher education. We hope this paper will spark conversations within academic institutions about the importance of acknowledging the experiences of MCF, so that context-specific solutions can be developed. The literature that informed this paper and supported our experiences is just one piece of the puzzle. As a next step, we recommend conducting a formal scoping review to systematically map all the available literature on MCF. This would help identify key concepts, theories, research studies, and gaps in the research.

In this paper, we focused on the promotion from associate to full professors, but we recognize that there are similar challenges or barriers for promotions from assistant to associate professors. Additionally, while we chose to focus on women in academia and their struggles in the tenure and promotion (T & P) process, we acknowledge that the experiences of minority men represent a gap in the literature that could be explored in future studies.