1. Introduction

Nowadays, with people spending up to 90% of their time indoors, exposure to compromised indoor air quality (IAQ) has emerged as a major concern for public health. In 2019 alone, World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that household air pollution was responsible for nearly 86 million lost healthy life years, with the greatest burden affecting women in low-income and middle-income countries [

1]. In the same year, WHO attributed more than 7 million annual deaths, including 3.2 million premature deaths, to exposure to poor IAQ conditions, among which 237,000 occurred in children under the age of 5. With more than 750 million people experiencing energy poverty worldwide, widespread reliance on polluting fuels for cooking and heating remains prevalent, further compromising IAQ in vulnerable households. Therefore, improving air quality has been prioritized in the action plans and policy frameworks of the European Union and the United Nations, aligning with the broader objectives of sustainable development, climate resilience, and health equity [

2,

3].

Indoor air is degraded by numerous pollutants, which are broadly classified as chemical contaminants and biological agents. Chemical contaminants encompass gaseous pollutants—such as carbon oxides (CO

x), nitrogen oxides (NO

x), ozone (O

3), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—as well as particulate matter (PM). PM represents a complex mixture of solid and liquid particles suspended in air, categorized by aerodynamic diameter into fractions such as PM

1, PM

2.5, and PM

10. A systematic review of 141 IAQ studies conducted across 29 countries revealed that PM

2.5 was the predominant research focus, being investigated in 73 of these studies [

4]. This focus is not incidental; nearly all established environmental standards have identified PM

2.5 as a critical indicator in IAQ assessment, recognizing its causal links to adverse health outcomes. Of particular concern, a range of respiratory diseases have been associated with PM

2.5 including lung cancer [

5], increased susceptibility to respiratory infections such as influenza [

6], and cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension [

7,

8].

To mitigate these health risks, health organizations, environmental regulatory bodies, and scientific institutions have established standards and guidelines that define the acceptable concentration limits for prevalent air pollutants based on exposure duration. Among the existing European standards and guidelines, the most commonly referenced short-term exposure limits for PM

2.5 are 40 µg/m

3 for the 8 h mean and 25 µg/m

3 for the 24 h mean, while the stipulated annual limit is set at 15 µg/m

3 [

9]. The WHO guidelines propose more health-protective and stringent limits for PM

2.5, recommending mean concentrations of 15 µg/m

3 over 24 h and 5 µg/m

3 annually. Alarmingly, WHO has reported that nearly 99% of the global population remains exposed to pollutant concentrations exceeding these thresholds [

10].

Recent advances in sensing technologies have helped bridge the long-standing gap between IAQ policies and their practical implementation, enabling accurate yet cost-effective monitoring of air pollutants. The rise of wearable and portable sensors has accelerated the paradigm shift toward personalized IAQ monitoring, marking a transition from spatially averaged measurements to characterization of contamination dynamics within the human microenvironment. Harnessing lightweight communication protocols, edge computing, and data analytics, sensors have evolved into the backbone of modern, smart IAQ ecosystems, facilitating an integrated, end-to-end approach to air quality management and predictive modeling [

11]. Nevertheless, limitations in spatial coverage and multi-sensing capabilities still constrain their scalability in real-world applications. In response, virtual sensing has gained prominence, reliably estimating air pollutants concentrations through sparse sensing networks using advanced spatio-temporal interpolation methods and data fusion techniques [

12].

Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are emerging as pivotal enablers of IAQ modeling, driving a transition from reactive monitoring systems toward data-driven, adaptive solutions [

13]. Beyond forecasting, AI/ML could be instrumental in improving sensors’ accuracy and reliability through low-cost calibration [

14,

15,

16] and expanding their spatial coverage through virtual sensing [

17]. The advent of Large Language Models (LLMs) has revolutionized the AI landscape, spurring significant advances in natural language understanding and human–machine interaction. Increasingly, these models are being explored as tools for integrating conversational interfaces with analytical and forecasting workflows in IAQ applications [

18]. By doing so, LLMs foster the democratization of air quality knowledge by providing accessible insights on air pollution, its associated health implications, and effective ventilation strategies [

19].

The main research objective of this work was to introduce a human-centric framework aimed at forecasting PM2.5 5 min ahead at the human immediate proxies. Integral to this framework is a low-cost, arm-worn wearable device that enables precise estimation of immediate PM2.5 exposure in a minimally intrusive manner. Such a human-centric approach eliminates the need to interpolate room-level measurements to human-proximal conditions, facilitating personalized exposure estimation, health risk assessment, and proactive air-filtration management.

The remainder of this paper is articulated as follows.

Section 2 reviews prior studies in IAQ domain with relevant research objectives.

Section 3 describes the wearable device and the data collected, explores its main distributional characteristics and dependencies, and presents the attention-based LSTM architecture.

Section 4 evaluates the proposed framework’s predictive performance. Finally,

Section 5 discusses the research findings.

2. Related Works

The robust performance of deep learning architectures in PM2.5 forecasting has been consistently substantiated across several studies, with LSTM emerging as one of the principal focal points in recent research. Integrated LSTM and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) approaches have also received considerable research attention owing to their complementary strengths in modeling both temporal and spatial dependencies in PM2.5 dynamics. Integrated LSTM and Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) approaches have emerged as effective modeling paradigms to quantify uncertainty and support probabilistic decision-making in IAQ domain. Ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) has proven to be a prominent technique for decomposing complex, non-stationary time-series into interpretable temporal modes, enhancing the learning efficacy of LSTM models. The remainder of this section outlines methodological approaches proposed for PM2.5 prediction, and reports their performance in terms of Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE).

Hybrid CNN-LSTM approaches for PM

2.5 forecasting have been investigated in three studies targeting a 1 h ahead horizon. Huang and Kuo [

20] proposed a CNN-LSTM multilayer structure with augmented attention mechanism termed Attention-based Parallel Networks (APNet), where a 1D-CNN extracts local spatial structures in PM

2.5 concentrations and an LSTM captures their temporal correlations. Using multivariate input sequences comprising cumulative PM

2.5 levels, wind speed, and rainfall duration from the preceding day, APNet achieved a MAE of 14.63 µg/m

3 and an RMSE of 34.23 µg/m

3, outperforming standalone CNN and LSTM configurations. Zaini et al. [

21] developed a hybrid CNN-LSTM model, leveraging a two-year dataset with outdoor air quality measurements from two monitoring stations in Malaysia. Although the hybrid model exhibited superior performance compared to standalone CNN and LSTM configurations, applying EEMD further enhanced the accuracy of the standalone LSTM, yielding a MAE of 2.8 µg/m

3 and an RMSE of 4.9 µg/m

3. Under a similar experimental design involving two outdoor air quality monitoring stations in Beijing, Bai et al. [

22] implemented an LSTM preceded by EEMD-based time-series decomposition. Their model reported comparable accuracy metrics for the two monitoring sites: RMSE of 14.0 µg/m

3 and 12.1 µg/m

3, MAPE of 19.6% and 16.9%, and R

2 of 0.994 and 0.991. Chae et al. [

23] developed an interpolated CNN designed to predict PM

2.5 concentrations in unmonitored areas, yielding an R

2 of 0.97 with an RMSE accounting for 16% of the concentrations’ variability.

In contexts emphasizing temporal rather than spatial PM

2.5 variability, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have emerged as particular effective approaches. Prihatno et al. [

24] demonstrated the superior performance of bidirectional RNN architectures over unidirectional LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and Transformers in PM

2.5 forecasting. The bidirectional LSTM yielded comparable MAE of 2.65 µg/m

3 and 2.67 µg/m

3 for 5 min and 30 min ahead, respectively, and 3.95 µg/m

3 for 1 h ahead. X. Dai et al. [

25] employed an RNN to enable automated control actions in residential ventilation systems, combining an autoencoder with a recurrent processing layer. For 30 min ahead, it achieved MAE values of 8.3 µg/m

3 and 9.2 µg/m

3 for PM

2.5 levels below and above 50 µg/m

3, respectively. P. Karaiskos et al. [

26] applied an LSTM model to predict future time intervals expected to satisfy the threshold values stipulated in IAQ standards and guidelines, thereby assessing periods of healthy environment. Conducting experiments in a naturally ventilated fitness center in Texas, the model achieved an 85.7% detection rate. Lagesse et al. [

27] argued that LSTM models could serve as viable alternatives to costly monitoring devices, enabling PM

2.5 forecasting using data from open, low-cost, and high-end sensors. With 5 min granularity, LSTM achieved normalized RMSE of 0.024 µg/m

3, nearly matching the precision observed when using expensive nephelometers instrumentation, thereby reducing the cost barrier for building managers seeking actionable IAQ insights.

Beyond the IAQ domain, gradient boosting algorithms have shown notable performance in time-series forecasting, effectively capturing complex non-linear relationships among temporal features; however, their practical implementation in real-world IAQ application remains limited. A. Singh et al. [

28] developed an XGBoost to forecast PM

2.5 concentrations one-hour ahead attaining a MAPE of 0.040% and an RMSE < 10

−3 µg/m

3 that outperformed deep learning architectures including LSTM.

BNN architectures aimed at predicting indoor PM

2.5 concentrations were explored in two studies. First, H. Dai et al. [

29] employed a BNN leveraging an extensive IAQ dataset comprising more than 1.4 million records to predict average day-ahead PM

2.5 levels across residential settings in China. This model incorporated socioeconomic factors as additional predictors to enhance its accuracy, achieving a MAE of 9.45 µg/m

3 and an RMSE of 13.3 µg/m

3. Utama et al. [

30] proposed an integrated BNN-LSTM architecture to forecast PM

2.5 at 1-, 2-, and 3 h horizons, yielding MAE values of 0.90 µg/m

3, 2.94 µg/m

3, and 3.31 µg/m

3 for the respective horizons, outperforming LSTM and CNN-LSTM configurations.

Z. Zhang and S. Zhang [

31] introduced a novel Sparse Transformer Network (STN) with a multi-head attention-mechanism in both encoder and decoder sides aimed at minimizing computational overhead and processing time. Evaluated against CNN, LSTM, and Transformer architectures at two locations in China over 1, 6, 12, and 24 h horizons, it exhibited an optimal MAE of 3.76 µg/m

3 for Taizhou and 11.13 µg/m

3 for Beijing. Mahajan et al. [

32] implemented a univariate time-series model using exponential smoothing with drift (ESD) leveraging data from 132 IoT-based air quality monitoring stations in Taiwan. The proposed model outperformed traditional time-series models and DL architectures, attaining a MAE of 0.16 µg/m

3.

3. Methods and Materials

Section 3 outlines the materials and methods underpinning the proposed predictive framework for estimating personalized PM

2.5 exposure.

Section 3.1 presents the low-cost wearable device used to collected PM

2.5 measurements from the human immediate proxies.

Section 3.2 examines the distributional characteristics underlying the collected data.

Section 3.3 explores temporal patterns and dependencies in PM

2.5 measurements.

Section 3.4 describes the architecture of the attention-based LSTM models.

Section 3.5 defines the metrics used to evaluate their predictive performance.

3.1. Wearable Device and Data Collection

The low-cost wearable device deployed to monitor an individual’s direct exposure to PM

2.5 integrates a Sensirion SPS30 optical particle counter based on laser-scattering principles [

33]. This sensor detects particles within the 0.3–10 µm aerodynamic diameter range and computes cumulative mass concentrations for PM

1, PM

2.5, PM

4, and PM

10. It operates within a temperature range of −10 °C and 60 °C and a relative humidity range of 0% and 95% (non-condensing), and provides digital outputs through Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter (UART) and Inter-Integrated Circuit (I

2C) interfaces. According to the Sensirion specifications, SPS30 exhibits a precision error of

for PM2.5 concentrations below 100 μg/m

3, under reference conditions (25 °C and nominal supply voltage) [

34].

The SPS30 incorporates advanced contamination-resistance mechanisms to mitigate the effects of dust accumulation and humidity. To further enhance measurement precision under varying humidity conditions, a calibration model based on the humidity-adjustment equations proposed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was applied to the raw PM

2.5 measurements, compensating for hygroscopic particle growth that causes artificial overestimation in light-scattering sensors and aligning the results with reference-grade monitors [

35,

36]. The EPA model addresses this effect through a set of piecewise regression equations that correct the uncalibrated sensor output

as a function of relative humidity

. Specifically, for

µg/m

3, the calibrated concentration

is given by Equation (1).

PM2.5 measurements are recorded at a 5 s resolution and transmitted to the microcontroller via the Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) bus, which facilitates both data logging and wireless communication. The LoRaWAN system-on-chip STM32WL55 was integrated into the mainboard, ensuring low-power operation, long-range connectivity and reliable data transmissions. The wearable device is powered by a 1600 mAh lithium-polymer battery with dual charging options: USB Type-C and a photovoltaic panel, allowing for extended operation without frequent recharging.

As presented in

Figure 1, the wearable device was worn on the upper right arm of a municipal office worker in Trikala, Greece, conducting continuous 8 h monitoring sessions over a 3-month period during typical morning office hours. The arm-worn configuration was considered as the optimal placement strategy, as it balanced the need to maintain proximity to the respiratory intake area while minimizing discomfort, obtrusiveness, and workflow disruption. Data acquired from the wearable device was published to a dedicated topic of an MQTT broker and stored in a PostgreSQL time-series database, resulting in a comprehensive data collection with 518,512 samples of PM

2.5 concentrations.

Although a 5 s sampling interval captures fine-scale fluctuations essential for real-time IAQ monitoring, it introduces two major challenges. First, high granularity time-series are prone to short-term noise and sensor artifacts that may not reflect meaningful variations. Second, from an ML perspective, such a high temporal resolution increases computational overhead and the risk of overfitting to noise. To address these challenges, a conservative aggregation strategy was employed, whereby batches of 12 consecutive samples were combined into a single representative one using median as the aggregation function. The resampling process yielded a reduced dataset with .

Let

denote the measured PM

2.5 concentration at a specific time step

. Then, the univariate input vector sequence

for the LSTM model, starting at position

with a temporal context window of length

, is formulated as in Equation (2).

Let

denote the horizon at which a single-step prediction is produced by the LSTM model parametrized by

. Then, the estimated PM

2.5 concentration at that horizon is defined as in Equation (3), where

represents the set of input sequences used for model training.

3.2. Distributional Characteristics for PM2.5 Levels

As a preliminary step, the principal distributional characteristics of

were explored to gain insights into the central tendency and variability of the PM

2.5 measurements, with the results illustrated by the boxplot in

Figure 2. The mean concentration was

, corresponding to a coefficient of variation of

, which indicated pronounced PM

2.5 fluctuations during the monitoring period. This considerable dispersion was advantageous for the model training, as it exposed the model to diverse and non-stationary PM

2.5 patterns. Also, the average PM

2.5 concentration remained well below the acceptable upper limit of

reflected in European standards [

9] for long-term exposure; however, it exceeded the more restrictive WHO guideline

. The median PM

2.5 concentration at

suggested highly symmetric central distribution.

The quartile breakdown revealed a narrow interquartile range (IQR) of , with positioned at and positioned at , implying limited dispersion among the central 50% of measurements. Despite that narrow IQR, multiple outliers were identified, predominantly above the upper whisker at , indicative of intermittent spikes in PM2.5 concentrations over the monitoring period. This outlier prevalence allowed for a more rigorous evaluation for the model’s robustness beyond typical patterns governing PM2.5 concentrations, such as extreme contamination events. The minimum concentration observed was , while the maximum reached .

3.3. Exploration of Linear Dependencies and Sharing Information in PM2.5 Concentrations

3.3.1. Autocorrelation Patterns in PM2.5 Concentrations

Prior to autocorrelation analysis, the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) statistical test was conducted to assess the stationarity of the time-series, a necessary condition for valid autocorrelation inference. The test examined the null hypothesis of a unit root, whose presence would indicate non-stationarity driven by stochastic trends or random-walk components. With an ADF statistic of , well below the critical value of , and a p-value , the results provided strong statistical evidence to reject the null-hypothesis of a unit root, thereby confirming the stationarity assumption.

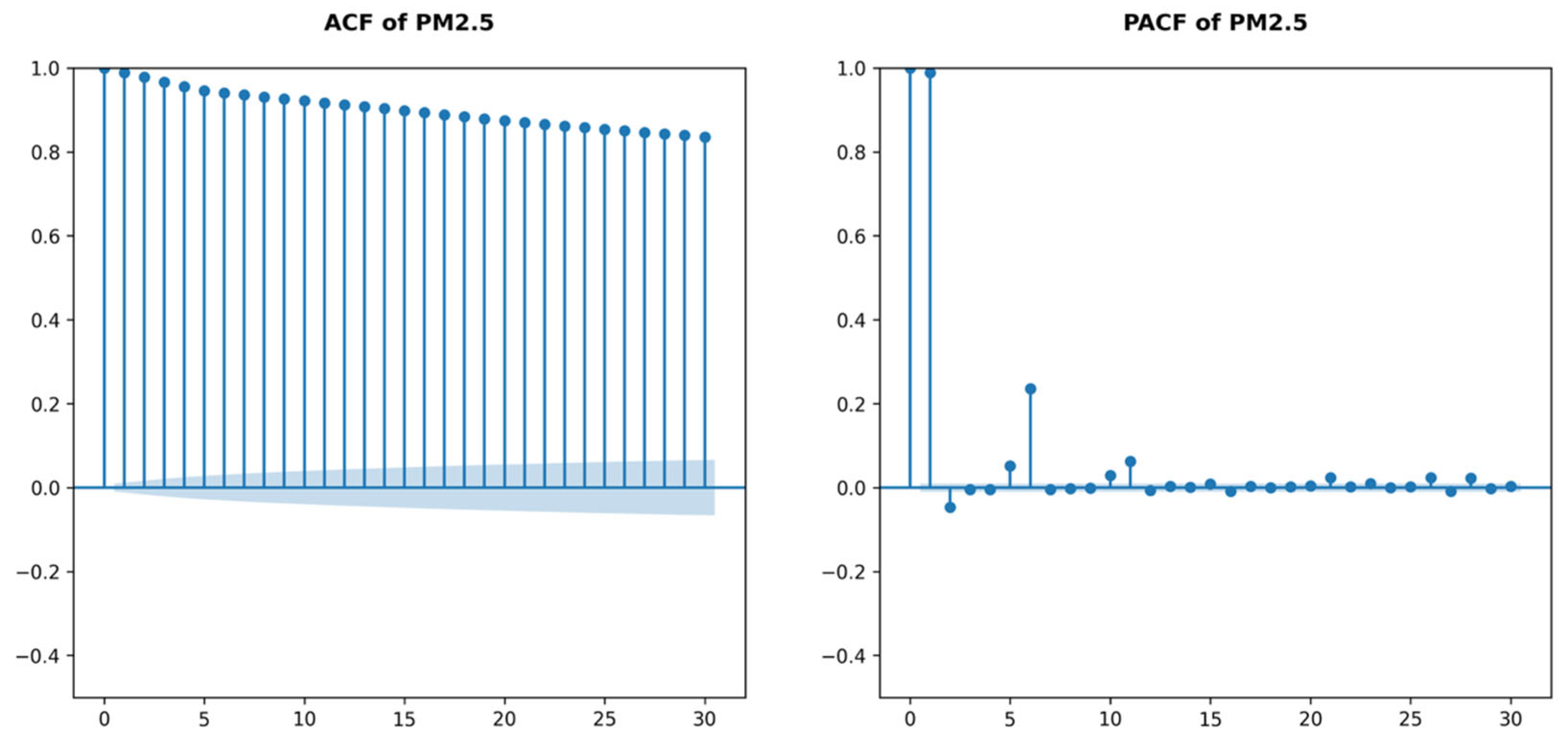

To analyze the temporal patterns under the stationarity assumption for the time-series PM

2.5 measurements, Autocorrelation (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Functions (PACF) were used, with their corresponding plots presented in

Figure 3. Aligned with the targeted short-term 5 min forecasting horizon, the lookback windows for both ACF and PACF were restricted up to 30 lagged values, representing PM

2.5 dynamics in the immediate human surroundings over a 30 min period.

The ACF revealed strong and persistent autocorrelations in PM2.5 concentrations across the examined 30 min interval, with correlation coefficients . The gradual decline pattern in ACF values further supported the presence of long-memory characteristics in the time-series. In contrast, the PACF identified a dominant partial autocorrelation at lag-1 and a moderate secondary effect at lag-2. For subsequent lags, coefficients declined toward zero, except at lag-6, where a notable resurgence suggested a potential periodic component. In summary, the most recent PM2.5 concentrations emerged as the primary predictive drivers for short-term horizons, while higher-order lag effects were generally negligible.

3.3.2. Mutual Information in PM2.5 Concentrations

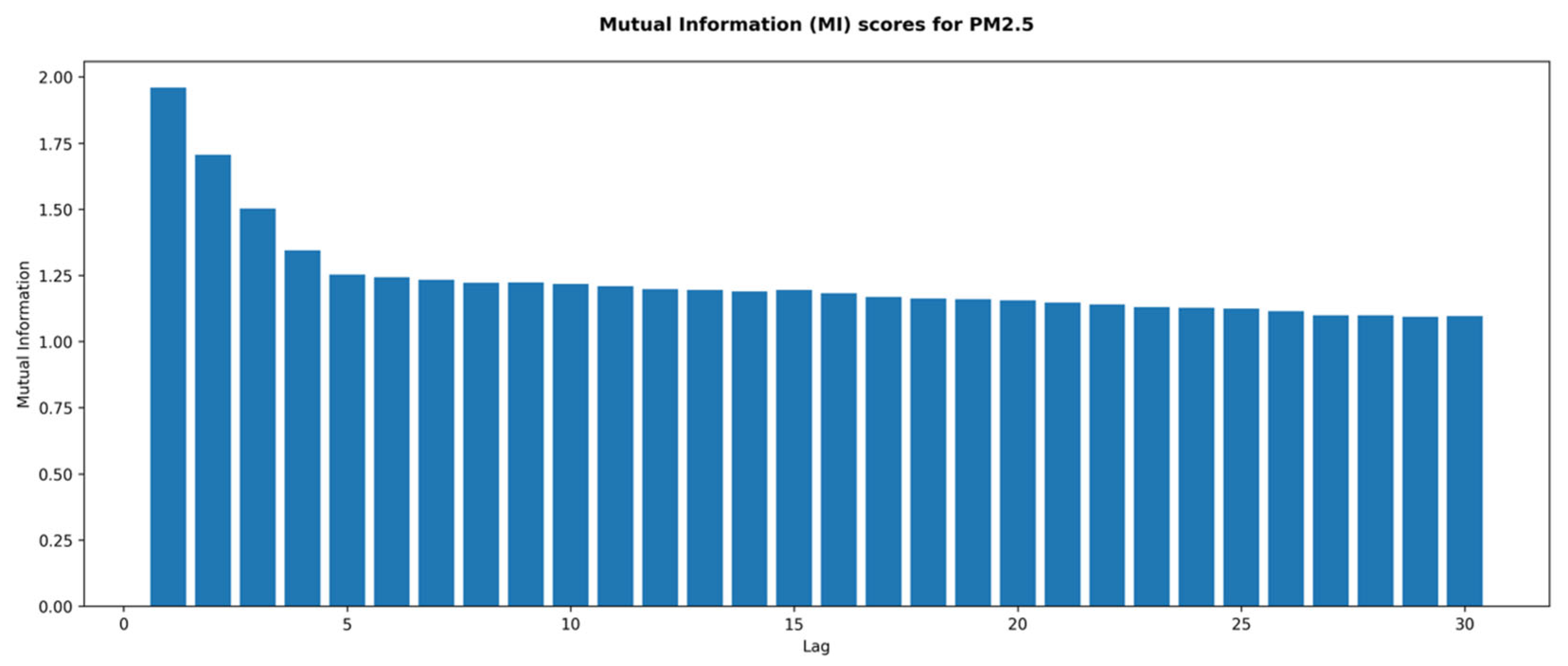

A limitation of ACF and PACF is that they primarily capture linear temporal dependencies, whereas more complex non-linear relationships may exist across different lag intervals in PM2.5 concentrations. Despite this limitation, the immediate lags at 1, 2, and 5 steps warrant particular attention due to their strong linear predictive signals.

The Mutual Information (MI) measure was employed to quantify the shared information between the current PM2.5 levels and their lagged counterparts up to 30 steps prior. This information-theoretic measure does not assess non-linearity per se, but determines the total statistical dependence through uncertainty reduction in current PM2.5 concentrations given knowledge of preceding ones. Consequently, when analyzed in conjunction with the ACF and PACF, it facilitates the identification of latent temporal and non-linear dependencies in PM2.5 dynamics.

Figure 4 illustrates the results of the MI analysis. At the shortest lags, MI revealed pronounced shared information among PM

2.5 concentrations, particularly up to lag-5, with MI scores of 1.95, 1.68, 1.49, 1.35, and 1.25. From lag-5 onwards, MI scores reached a plateau around 1.10, demonstrating weaker yet detectable dependencies. These results contrasted with those obtained from the PACF, where linear dependencies diminished after lag-2, except for a resurgence at lag-5, suggesting the presence of non-linear components.

3.4. Modeling PM2.5 Using an Attention-Based LSTM Architecture

The dataset was partitioned into training and testing subsets using an 85/15 split ratio that preserved the chronological structure of the time-series, allocating the most recent 15% of the measurements to . The resulting holdout set, comprising 6481 unseen samples, provided an unbiased estimate of the model’s generalization performance. A walk-forward validation was applied to using 5 temporal splits to reduce the period-specific bias inherent in single chronological train-validation splits, thereby enhancing generalization robustness through multiple independent evaluations across distinct time intervals and avoiding data leakage. Each fold involved expanding training windows and non-overlapping sequential validation sets, maintaining a 70/30 ratio and progressively incorporating additional measurements for training.

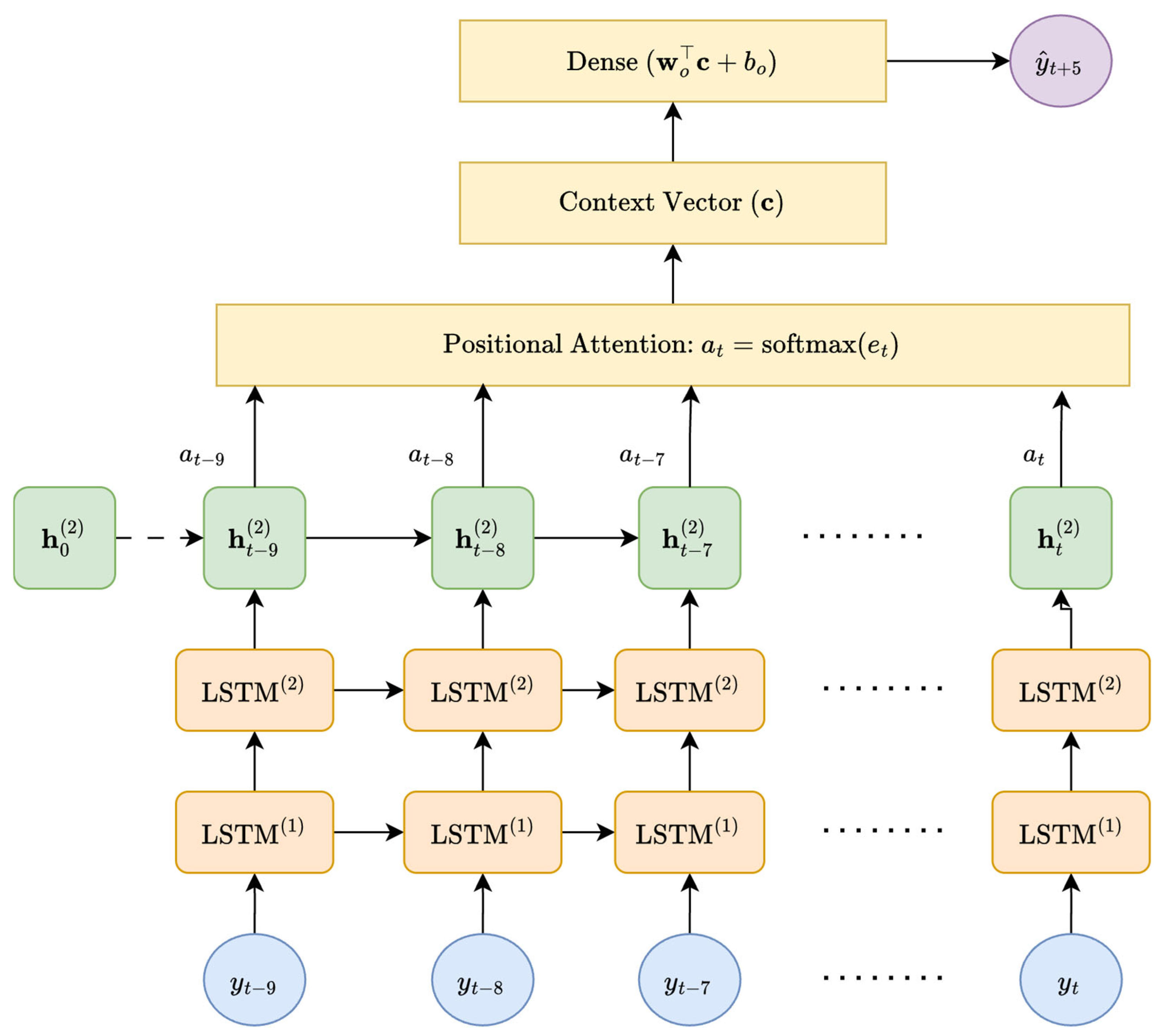

An attention-based LSTM model was employed to produce single-step predictions of PM

2.5 concentration, denoted as

, at a forecasting horizon of

min, using univariate input sequences

consisting of

consecutive PM

2.5 measurements. This 10 min lookback window was selected according to the findings reported in

Section 3.3, which evidenced strong temporal dependencies in PM

2.5 concentrations over this time range. Specifically, the ACF exhibited a persistent autocorrelation pattern with a gradual decay extending up to 30 min, while the PACF revealed that the dominant direct temporal dependencies were mainly confined to short lags (up to two minutes), with a secondary peak at lag-6. MI corroborated these findings, exhibiting asymptotic information convergence well before 10 min, thereby confirming that the key predictive information resides within the selected temporal window.

The proposed attention-based LSTM model integrated a deep, stacked LSTM encoder consisting of multiple gated recurrent layers that capture hierarchical temporal patterns, coupled with a custom positional attention mechanism designed to introduce a recency bias during sequence aggregation. Let

denote the depth of the stacked LSTM encoder and

represent the

-dimensional hidden state of the

-th LSTM layer at time step

. For an input sequence

, Equation (4) defines the computations in the first layer, where

denotes the PM

2.5 concentration at time step

; Equation (5) specifies each subsequent layer; and Equation (6) yields the model output

.

The custom positional attention mechanism implemented a learnable weighting scheme that encouraged the model to focus on the most informative timesteps within the input sequencies through explicit recency bias injection. Grounded in prior findings indicating that the most recent PM

2.5 measurements carry the highest predictive importance, this mechanism combined a trainable attention weight vector

with a monotonically increasing deterministic temporal bias to prioritize the most recent hidden states. Softmax normalization was applied to attention scores

computed over the sequence of hidden states

from the final LSTM layer, allowing the mechanism to perform differentiable, adaptive temporal aggregation across the entire lookback window. Let

denote the learned bias for each position

and

denote the fixed positional bias for each time step

. The, the computation of the attention scores, normalized weights, and context vector follows Equations (7)–(9).

The output layer of the proposed LSTM architecture consists of a fully connected dense layer

that maps the attention-aggregated context vector

to the final prediction

. It applies a linear transformation with a learned weight vector

and bias term

to the context vector

, yielding a scalar output corresponding to the predicted PM

2.5 concentration at the desired 5 min forecasting horizon, as defined in Equation (10).

During training, the LSTM variants were optimized to minimize the loss function

of the Mean Squared Error (MSE), as described in Equation (11), where

denotes the batch size. In addition, early stopping was applied for model regularization, terminating the training at epoch

when the validation loss

plateaued using a patience of 4 epochs.

Figure 5 depicts the proposed attention-based LSTM architecture. The model ingests univariate input sequences of 10 consecutive PM

2.5 measurements, representing a 10 min lookback window. Two stacked LSTM layers encode temporal dependencies and produce hidden states for each time step, which are subsequently weighted by a positional attention mechanism (softmax-normalized) according to their relevance. The resulting context vector aggregates the weighted hidden representations and is passed through a dense output layer to generate the forecasted PM

2.5 concentration 5 min ahead.

3.5. Hyperparameter Tuning for Attention-Based LSTM Performance

Given the prohibitive computational overhead introduced when pursuing exhaustive grid searches during the hyperparameter tuning process in DL problems, the present study adopted a history-aware Bayesian optimization approach that strategically navigated across a mixed discrete-continuous high-dimensional hyperparameter space

, facilitating the early pruning of unpromising architectures and configurations. The key idea behind this approach is to model the probability distributions of different hyperparameter configuration vectors

conditioned on their observed predictive performance utilizing the Tree-structured Parzen Estimators (TPE) technique. In each iteration, an acquisition-based optimization problem was formulated to inform the selection of subsequent candidate configuration vectors

toward promising regions of the hyperparameter space

, likely to minimize an objective cost-function

reflecting the validation loss, as expressed in Equation (12).

The coarse-to-fine paradigm was followed to initially explore a broad hyperparameter space comprising multiple hierarchical sequential LSTM structures, learning rates, regularization strengths and patterns. Subsequently, a narrower hyperparameter space was constructed, concentrated around those regions that proximate the global minimum of the objective cost-function in terms of validation error.

For the initial space

, shallow-to-deep sequential LSTM architectures were investigated that comprised

layers with a monotonical decreasing pattern of

units per layer. These configuration parameters were selected to align with the limited problem’s temporal scope. To further mitigate overfitting risk, different dropout strategies

were explored with rates

, including (i): no-dropout

with all rates equal to zero, (ii): uniform dropout

with equal rates across the layers, (iii): pyramid dropout

with peak rates at the middle layers, and (iv): terminal-heavy dropout

with stronger regularization at the terminal layer. Learning rate and L2 regularization strength encompassed values within continuous ranges, restricted to

and

. The complete configuration space

investigated for the initial model search is summarized in Equation (13).

For the refined space

, a tightened grid of parameters was explored capitalizing on the results from the

best-performing configurations in

. A key distinction from the previous search was that learning rates

and L2 regularization strengths

were restricted to a discrete set of two values, representing those overperformed across the prior explorations in

. The refined configuration space

explored is defined in Equation (14).

3.6. Evaluation Metrics for Attention-Based LSTM Performance

The implemented attention-based LSTM variants were evaluated using the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), defined in Equation (15), where

denotes the total number of samples in

. This metric quantifies the average magnitude of absolute errors regardless their direction, that is, the absolute difference between the actual

and the predicted

. MAE was also employed as a complementary metric to the training and validation losses during each training epoch.

4. Results

Section 4 reports the comparative performance of attention-based LSTM variants in forecasting PM

2.5 concentrations 5 min ahead.

Section 4.1 outlines the hyperparameter optimization process.

Section 4.2 then presents the training and validation of the three best-performing model configurations identified through optimization and assesses their predictive performance on unseen data.

4.1. Results from Hyperparameter Tuning for Attention-Based LSTM

An iterative optimization process with 40 trials was conducted to explore configurations across the hyperparameter space , aiming to minimize the validation MAE. Each trial comprised 3 independent training runs to account for stochasticity introduced by random weight initializations. All models were trained for up to 150 epochs, with an early stopping mechanism applied using a patience of 3 epochs and an improvement threshold of to prevent overfitting.

In absence of prior domain knowledge, the search across

initiated with a random configuration, yielding a validation MAE of

in Trial 1 that outperformed all the subsequent trials up to Trial 15. Marginal performance gains were observed in Trial 15 with the validation MAE reducing to

under a configuration comprising a 3-layer LSTM architecture with [

8,

16,

32] units, a terminal-heavy dropout strategy with rates of 0.0, 0.1, and 0.2,

and

.

Two additional performance improvements occurred until the termination of the optimization process in . In Trial 23, the validation MAE was reduced at , adjusting the dropout strategy from terminal-heavy to no-dropout, and . The most pronounced improvement detected in Trial 35 in which the validation MAE was reduced at , refining model’s regularization using pyramid dropout strategy with rates 0.0, 0.1, and 0.0, and adjusting and . Throughout the exploration of , the validation MAE remained consistently within the narrow band of and , indicating stable convergence near the global minimum.

Based on the preceding results, the top-performing configurations were used to construct the reduced hyperparameter space , including 3- and 4-layer architectures with no-dropout, pyramid and terminal-heavy dropout strategies. The dropout rates were restricted to the discrete set , as weaker regularization produced lower validation MAE. Learning rates and L2 regularization strengths were not arbitrarily chosen; instead, they were limited to discrete sets, representative of the best performed magnitude orders: and .

The optimization process in

commenced with an initial validation MAE of

, which was marginally improved in Trial 3. In this trial, a 3-layer LSTM architecture with [

8,

16,

32] units per layer decreased the validation MAE by

utilizing uniform dropout rates of 0.2 across the layers,

and

. In Trial 24, the same architecture employed the pyramid dropout strategy with dropout rates of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.1,

, and

, resulting in an improved validation MAE improvement at

, beyond which no further gains were observed.

4.2. Results from Training Process for the Attention-Based LSTM Models

Following the hyperparameter optimization in

, the three best-performing attention-based LSTM variants were derived for subsequent modeling and evaluation, corresponding to the configurations yielding the lowest MAE (

Table 1). These variants were trained with a batch size of 32 for up to 150 epochs, using an early-stopping patience of 3 epochs and a minimum improvement threshold of

in validation loss.

The configuration C1 processed univariate input sequences of 10 consecutive PM

2.5 measurements through three stacked LSTM layers with 32, 16, and 8 units, respectively. It employed a pyramid dropout scheme with rates of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.1, and used a learning rate of

and an L2 regularization strength of

. This configuration exhibited a tri-phasic smooth monotonic convergence pattern in both training and validation curves, as illustrated in

Figure 6. An initial rapid descent was observed for both curves up to epoch 30, followed by gradual refinement over the subsequent 70 epochs, and a stable asymptotic behavior until epoch 120. The consistent gap between the curves and the absence of oscillations indicated stable learning without signs of overfitting. The early stopping mechanism was triggered after 120 epochs, restoring the LSTM model from epoch 117 for subsequent evaluation. The model yielded a training MAE of 0.171 μg/m

3 and a validation MAE of 0.177 μg/m

3.

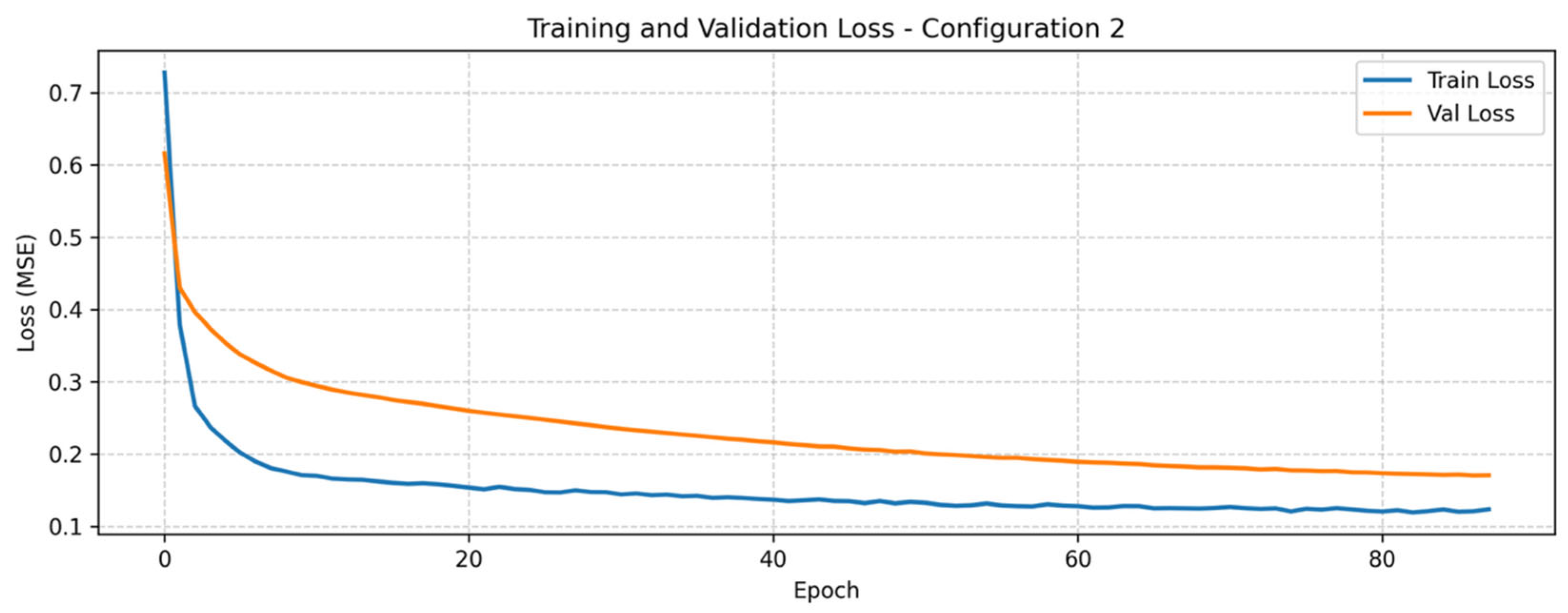

The configuration C2 processed univariate input sequences of 10 consecutive PM

2.5 measurements through three stacked LSTM layers with 32, 16, and 8 units, respectively. It employed a unform dropout strategy with rate of 0.2, using a learning rate of

and an L2 regularization strength of

. As illustrated in

Figure 7, this configuration exhibited congruent learning patterns with those of configuration C1, reaching an earlier plateau and being terminated by the early-stopping mechanism at epoch 84. A wider gap between training and validation curves was observed during the initial decay phase (25 epochs), followed by gradual refinement of both losses over the next 40 epochs. C2 showed a more resource-efficient learning process while achieving nearly identical predictive performance to the previous configuration. The model yielded a training MAE of 0.174 μg/m

3 and a validation MAE of 0.179 μg/m

3.

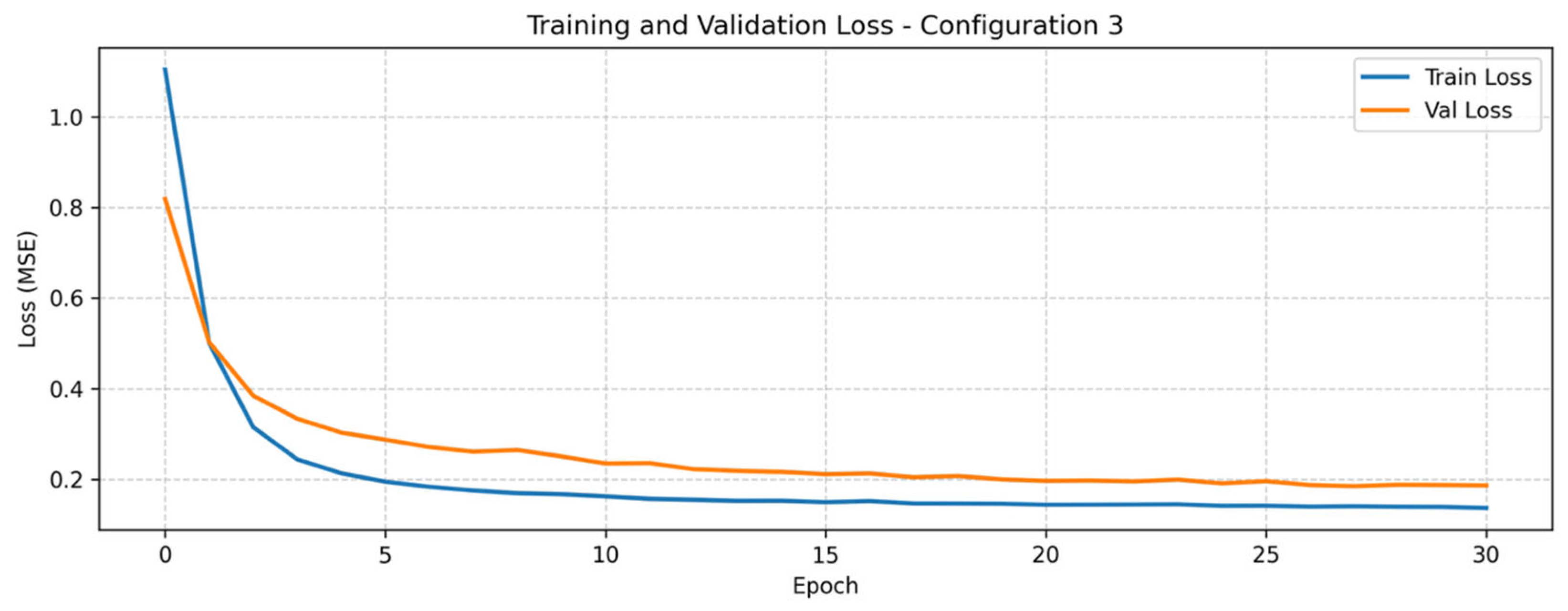

The configuration C3 processed univariate input sequences of 10 consecutive PM

2.5 measurements through three stacked LSTM layers with 32, 16, and 8 units, respectively. It employed a pyramid dropout strategy with rates of 0.0, 0.2, and 0.0, and used a learning rate of

and an L2 regularization strength of

. This configuration revealed a distinct learning pattern compared to the previous ones, as illustrated in

Figure 8. In particular, it showed accelerated convergence during the initial 10 epochs, despite using the same learning rate as in configuration C2. This steep decay pattern was likely attributable to reduced regularization constraints, reflected in the zero dropout rates of both the initial and terminal layers, partially offset by the higher L2 regularization strength. Unlike the previous configurations, C3 displayed a bi-phasic learning behavior, characterized by a rapid initial descent immediately followed by an early plateau, without gradual intermediate refinement. Erratic oscillations in the validation trajectory between epochs 10 and 20 indicated that performance gains in the training set were not consistently mirrored in the validation set. Training was terminated at epoch 30 by the early-stopping mechanism due to the absence of meaningful validation improvements. The model yielded a training MAE of 0.178 μg/m

3 and a validation MAE of 0.193 μg/m

3.

Table 2 summarizes the quantitative performance of the three configurations across the training and validation. The results highlighted consistent learning dynamics among the models, with configuration C1 achieving the most stable convergence and the lowest MAE, followed by C2 with marginally higher errors and C3 showing reduced learning stability.

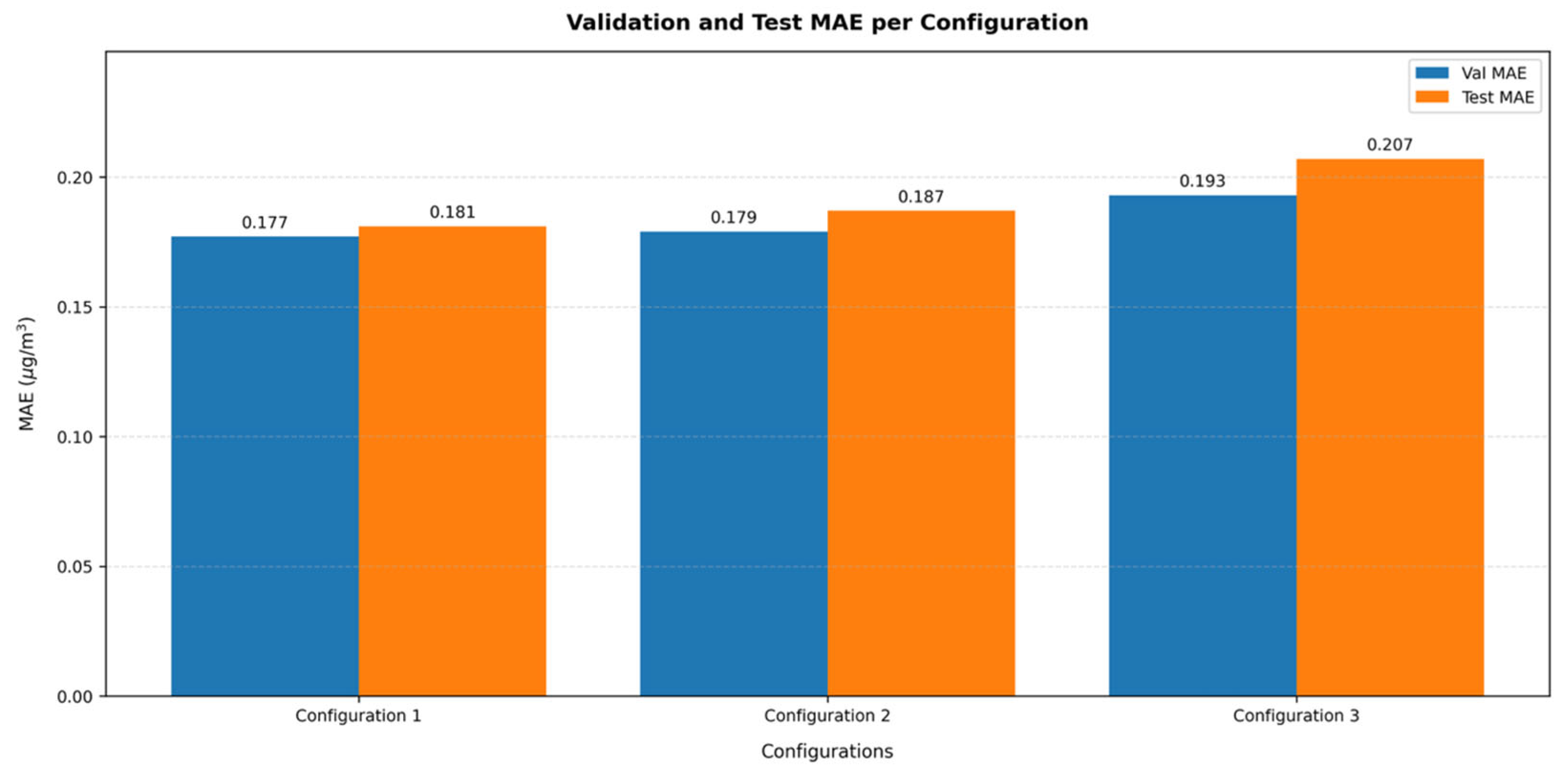

4.2.1. Performance Evaluation for the Attention-Based LSTM Models

The validation and test MAE that obtained from the three different hyperparameter configurations C1, C2, and C3 are presented in

Figure 9.

The configuration C1 achieved the optimal predictive performance, corresponding to the lowest validation and test MAE of and , respectively. The consistent MAE in both validation and test sets with a 2.3% relative difference indicated robust model’s generalized and further confirmed its stable learning.

The configuration C2 demonstrated a comparable MAE of in the validation set, although it resulted in a 4.5% higher MAE in the test set at . This performance degradation on unseen data highlighted that the hyperparameter set for configuration C2 was more susceptible to overfitting and the training for fewer epochs limited the model’s learning capacity in more generic temporal dependencies.

The configuration C3 resulted in inferior performance compared to the previous ones, resulting in a validation MAE of and a testing MAE of , representing a performance degradation by 14.4% degradation when compared to the optimal configuration C1. The root cause was the truncated, bi-phasic learning and the erratic validation curve that led to premature overfitting. Despite the higher L2 regularization that attempted to compensate, the marginal validation improvements after epoch 10 and the early termination at epoch 30 further limited model’s generalization.

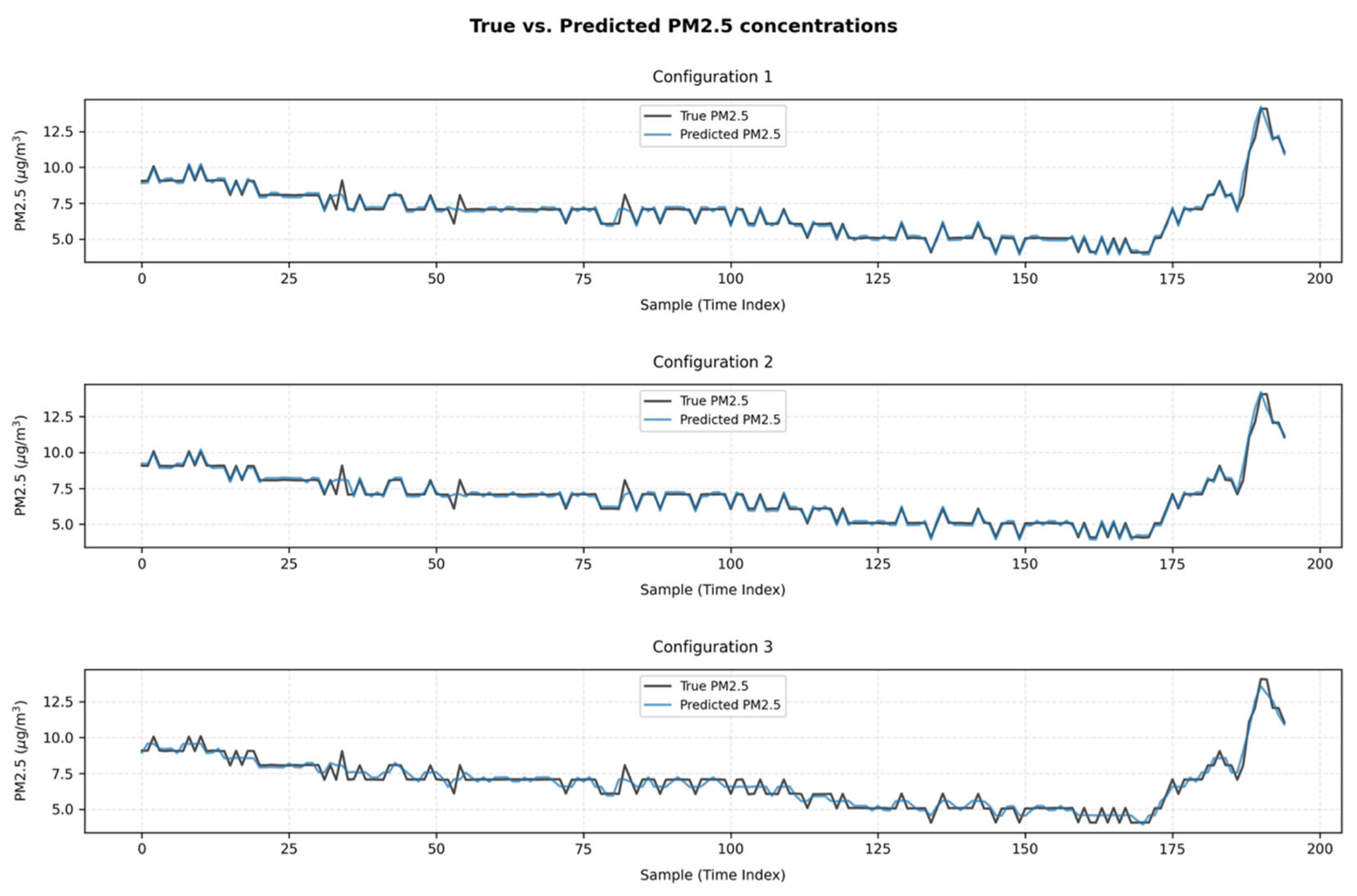

4.2.2. Visualization of the Attention-Based LSTM Models Predictive Accuracy

Figure 10 presents the comparative overview of predicted versus actual PM

2.5 concentrations for the three attention-based LSTM configurations, which accounted for a representative 50% of the hold-out test set with 195 non-overlapping single-step predictions.

The intuitive, visual examination provided convincing evidence for the superior predictive performance of configurations C1 and C2 compared to C3 throughout the time-series. Given the minimal residuals, the negligible overshoots and lags, and the close temporal tracking of the ground truth PM2.5 concentrations under steady-state conditions, both configurations established themselves as robust operational modeling approaches. The 4.5% MAE advantage of configuration C1 over C2 stems from its enhanced forecasting precision during stable pollution conditions, as both configurations achieved immediate magnitude and timing adaption to the transient spiked occurred at the final temporal segment.

In contrast, the configuration C3 demonstrated more pronounced deviations from the actual values and diminished temporal responsiveness. This configuration particularly struggled to capture the temporal onset and magnitude at the extreme contamination event, and during episodic, lower-amplitude spikes that occurred in the intermediate intervals. Despite these performance limitations, the configuration C3 preserved the general time-series trend and presented compelling computational advantages. Therefore, it constitutes a lightweight alternative for applications tolerating higher prediction uncertainty in exchange for reduced computational resources, such as continuous monitoring systems where approximate trend identification suffices.

5. Conclusions

This study introduced a human-centric approach for assessing short-term PM2.5 exposure, integrating wearable sensing with deep learning to translate predictive analytics into personalized IAQ insights. Τhe proposed approach employed a low-cost, arm-worn wearable device equipped with a Sensirion SPS30 sensor to unobtrusively capture PM2.5 dynamics within the human microenvironment. By functioning at the human-level, this device eliminated the need for spatial interpolation from room-level PM2.5 concentrations to individual exposure estimates, thereby reducing the demand for dense sensor deployments and computational resources. An LSTM with attention mechanism complemented the sensing module, modeling the temporal dependencies that govern human-level PM2.5 dynamics.

Το experimentally evaluate the proposed framework, three-month monitoring campaign was conducted in Trikala, Greece, that involved 8 h daily sessions with a municipal office worker, yielding 518,512 PM

2.5 samples collected at 5 s intervals. As presented in

Section 3.2, the examined office space exhibited relatively stable IAQ dynamics, while occasional contamination spikes served to evaluate model performance under stress conditions. As presented in

Section 3.3, the most pronounced dependencies in PM

2.5 concentrations observed at the immediate lags, maintaining significant autocorrelation and shared information persistence for up to 30 min. Accordingly, using a 10 min historical context for predicting PM

2.5 concentrations 5 min ahead proved to be an effective trade-off between temporal context length and computational overhead.

Following Bayesian hyperparameter optimization, the three best-performing attention-based LSTM variants were evaluated, each adopting a distinct architecture, regularization strategy, and learning rate. A 3-layer LSTM model comprising [

8,

16,

32] units per layer and a pyramid dropout with rates 0.0, 0.1, and 0.0,

and

achieved the optimal performance, reporting an MAE of 0.183 μg/m

3. Comparable performance, with a MAE higher only by 0.004 μg/m

3, was obtained from a 3-layer LSTM model employing uniform dropout rates of 0.2,

and

.

Beyond predictive accuracy, practical considerations related to device operation and user experience were also assessed. The wearable device was powered by a 1600 mAh lithium-polymer battery featuring dual charging options—USB Type-C and an integrated photovoltaic panel—which enabled continuous monitoring for three months with only five recharging cycles. The SPS30 sensor maintained stable performance throughout this period, supported by its built-in contamination-resistance mechanisms and the applied EPA-based humidity calibration that ensured measurement reliability under varying environmental conditions. The participant reported satisfactory comfort and unobtrusiveness during daily use; however, future iterations should emphasize further miniaturization and ergonomic improvements to enhance long-term user acceptability in real-world deployments.

Multiple research avenues warrant future investigation to advance and further elaborate this promising forecasting approach. First, the predictive performance of attention-based LSTM models across more extended horizons should be prioritized, also incorporating multi-variant input sequencies that comprises additional predictors for PM2.5 concentrations, including climatic conditions, gaseous pollutants, and occupancy status. Second, more sophisticated DL architectures should also be explored, such as Transformer networks and ensemble learning approaches, due to their strong capacity to model intricate temporal patterns. Third, to establish the proposed model’s robustness and generalization, it should be replicated and validated across indoor settings that experience diverse pollution concentration pattern and environmental conditions. Finally, the practical implementation of the proposed LSTM model with attention mechanism should be pursued in real-world environments, particularly through its integration with epidemiological and other health outcome models to enable personalized exposure-health risk assessment.