Lymphatic Spread of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Patterns, Staging, and Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

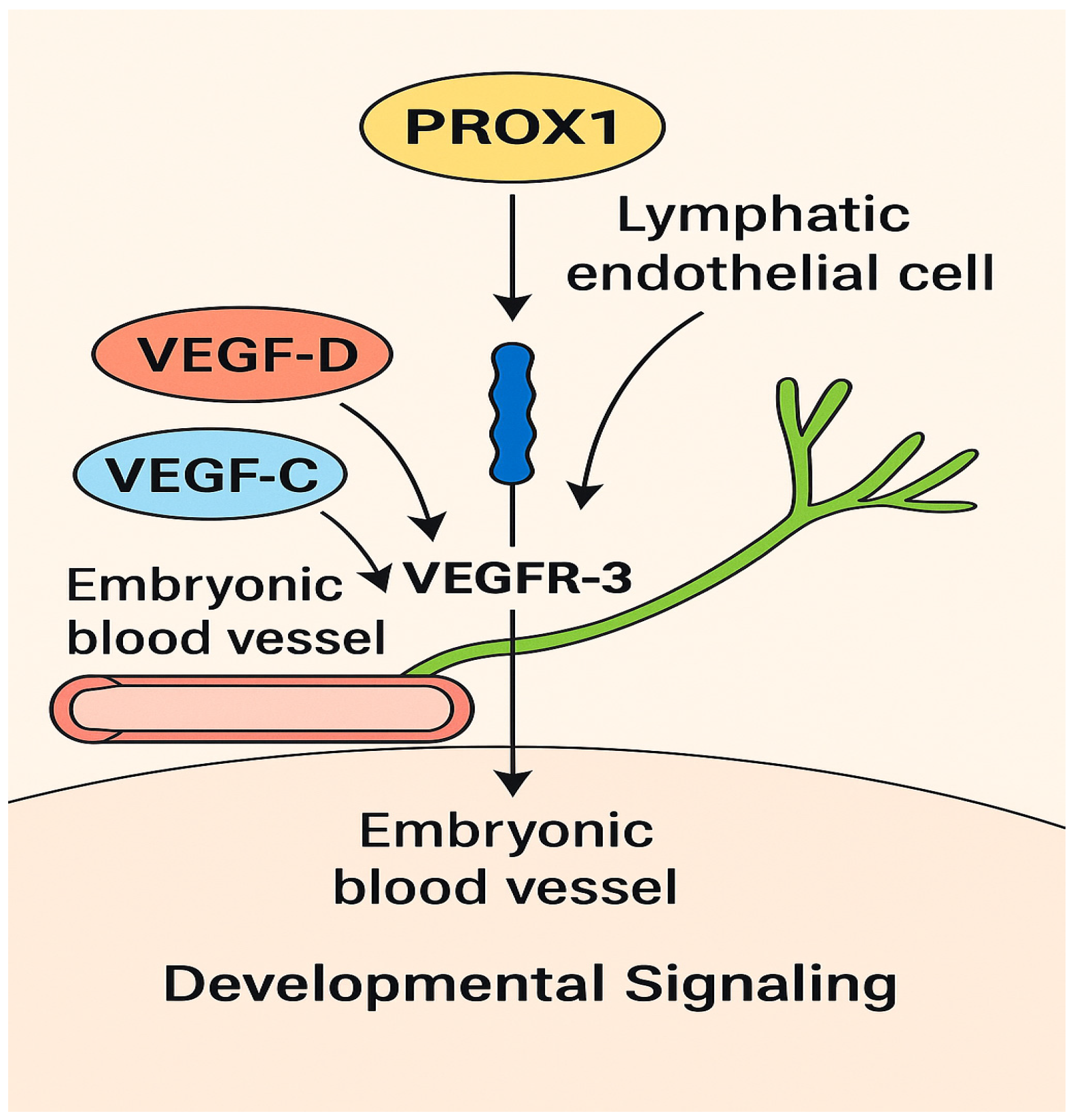

2. Lymphangiogenesis in NSCLC

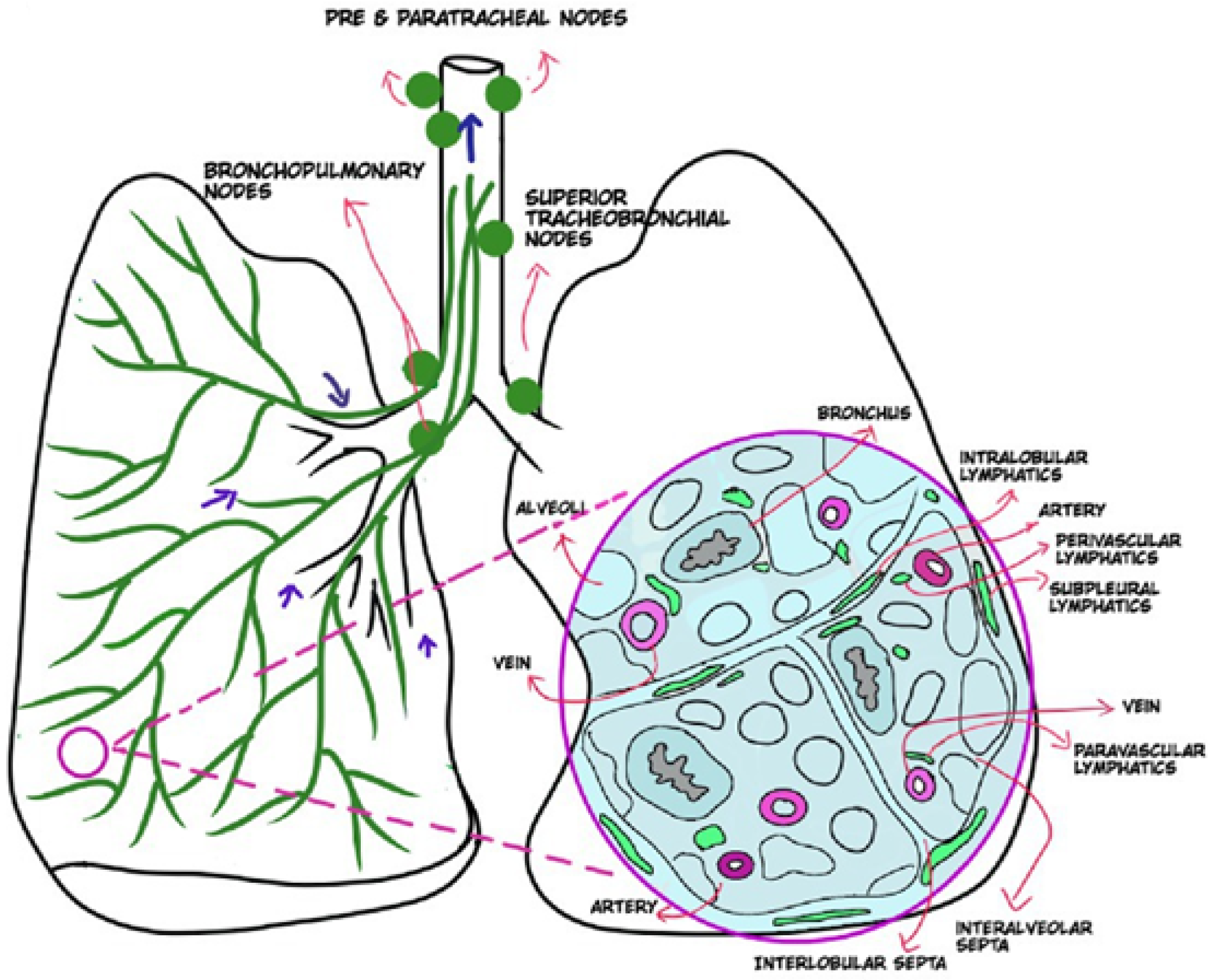

3. Normal Lymphatic Drainage Pathways

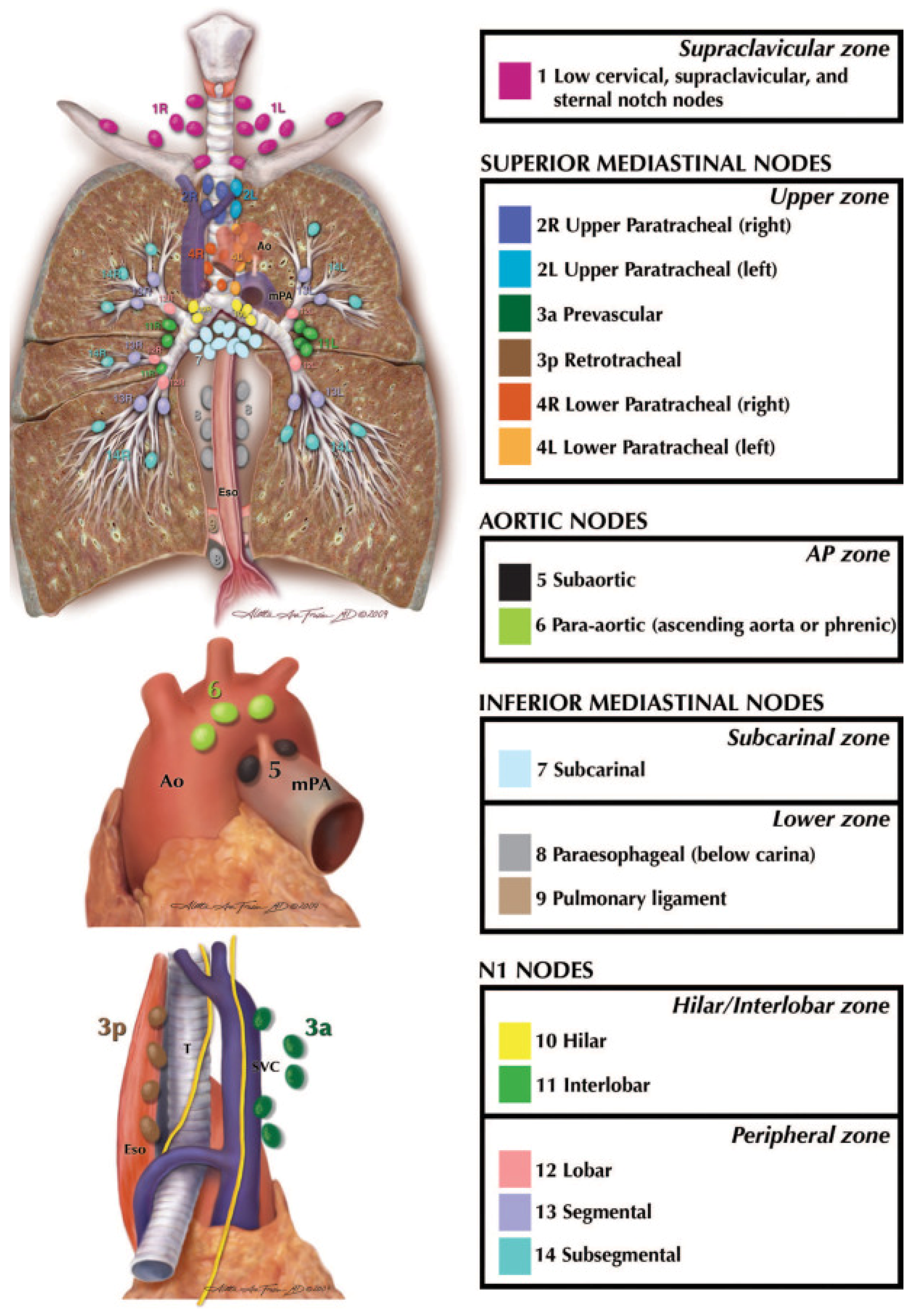

4. Patterns of Nodal Metastasis and Staging in NSCLC

5. How Tumor Location Influences Nodal Spread

6. Subtype-Specific Distribution

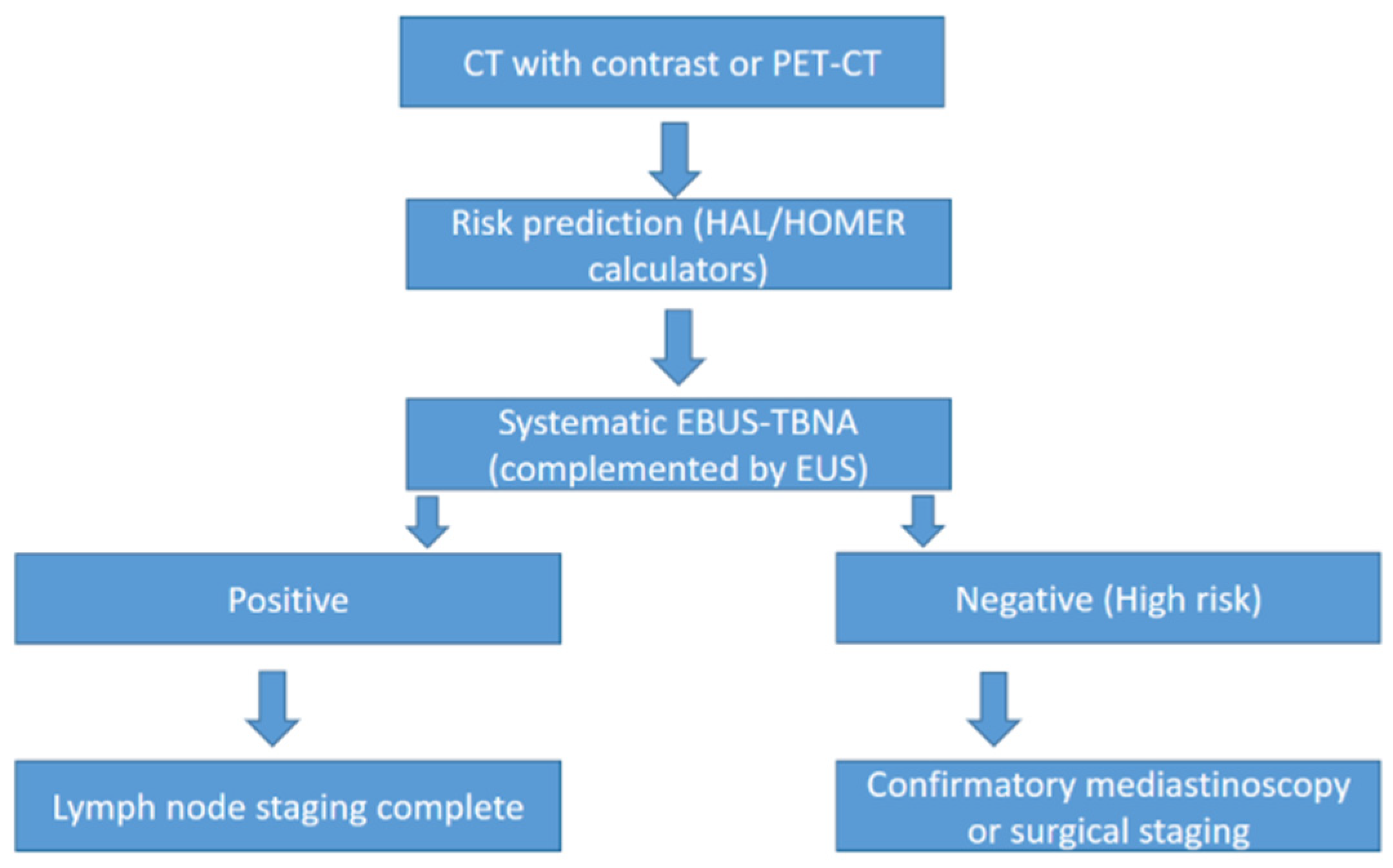

7. Clinical Prediction Tools for Nodal Metastasis

8. Advances in Lymph Node Sampling and Diagnostic Techniques

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49, Erratum in CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 203. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sankar, V.; Kothai, R.; Vanisri, N.; Akilandeswari, S.; Anandharaj, G. Lung cancer—A review. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2023, 13, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Shao, J.; Liu, D.; Li, W. Clinicopathological variables influencing overall survival, recurrence and post-recurrence survival in resected stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nicholson, A.G.; Tsao, M.S.; Beasley, M.B.; Borczuk, A.C.; Brambilla, E.; Cooper, W.A.; Dacic, S.; Jain, D.; Kerr, K.M.; Lantuejoul, S.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Advances Since 2015. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Boffa, D.J.; Kim, A.W.; Tanoue, L.T. The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. Chest 2017, 151, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, M.; Kirshenboim, Z.; Truong, M.T.; Sorin, V.; Ofek, E.; Agrawal, R.; Marom, E.M. Proposed Ninth Edition TNM Staging System for Lung Cancer: Guide for Radiologists. RadioGraphics 2024, 44, e240057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw, P.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Asamura, H.; Eberhardt, W.E.; Nicholson, A.G.; Groome, P.; Mitchell, A.; Bolejack, V.; et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, B.J.; Daly, M.E.; Kennedy, E.B.; Antonoff, M.B.; Broderick, S.; Feldman, J.; Jolly, S.; Meyers, B.; Rocco, G.; Rusthoven, C.; et al. Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Early-Stage Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the American Society for Radiation Oncology Evidence-Based Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanton, C.; Govindan, R. Clinical implications of genomic discoveries in lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1864–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, G.; Miller, P.G.; Agarwala, V.; Li, G.; Kaushik, G.; Backenroth, D.; Gossai, A.; Frampton, G.M.; Torres, A.Z.; Lehnert, E.M.; et al. Association of Patient Characteristics and Tumor Genomics with Clinical Outcomes Among Patients with Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Using a Clinicogenomic Database. JAMA 2019, 321, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, D.S.; Wood, D.E.; Aisner, D.L.; Akerley, W.; Bauman, J.R.; Bharat, A.; Bruno, D.S.; Chang, J.Y.; Chirieac, L.R.; DeCamp, M.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imyanitov, E.N.; Iyevleva, A.G.; Levchenko, E.V. Molecular testing and targeted therapy for non-small cell lung cancer: Current status and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 157, 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alitalo, A.; Detmar, M. Interaction of tumor cells and lymphatic vessels in cancer progression. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4499–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkinen, T.; Jussila, L.; Veikkola, T.; Karpanen, T.; Kettunen, M.I.; Pulkkanen, K.J.; Kauppinen, R.; Jackson, D.G.; Kubo, H.; Nishikawa, S.-I.; et al. Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis with resulting lymphedema in transgenic mice expressing soluble VEGF receptor-3. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, M.M.; Shang, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Expression of CXCR4 and VEGF-C is correlated with lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2017, 8, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liptay, M.J.; Grondin, S.C.; Fry, W.A.; Pozdol, C.; Carson, D.; Knop, C.; Masters, G.A.; Perlman, R.M.; Watkin, W. Intraoperative sentinel lymph node mapping in non-small-cell lung cancer improves detection of micrometastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1984–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.M.; Stowell, J.T.; Pope, K.; Carter, B.W.; Walker, C.M. Lymphatic Pathways of the Thorax: Predictable Patterns of Spread. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, K.; Lamattina, A.M.; Visner, G.; El-Chemaly, S. Lymphatic Vessels: The Next Frontier in Lung Transplant. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14 (Suppl. S3), S226–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Riquet, M.; Hidden, G.; Debesse, B. Direct lymphatic drainage of lung segments to the mediastinal nodes. An anatomic study on 260 adults. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1989, 97, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, A.; Reed, H.O. The lymphatic vasculature in lung function and respiratory disease. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1118583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G.R.; Trachiotis, G.D.; Mullenix, P.S.; Antevil, J.L. Minimally Invasive with Maximal Yield: A Narrative Review of Current Practices in Mediastinal Lymph Node Staging in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2024, 34, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Zhu, R.; Wu, D.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wan, Y. Application of computed tomography, positron emission tomography-computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, endobronchial ultrasound, and mediastinoscopy in the diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node staging of non-small-cell lung cancer: A protocol for a systematic review. Medicine 2020, 99, e19314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanz-Santos, J.; Serra, P.; Torky, M.; Andreo, F.; Centeno, C.; Mendiluce, L.; Martínez-Barenys, C.; de Castro, P.L.; Ruiz-Manzano, J. Systematic Compared with Targeted Staging with Endobronchial Ultrasound in Patients with Lung Cancer. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 106, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asamura, H.; Chansky, K.; Crowley, J.; Goldstraw, P.; Rusch, V.W.; Vansteenkiste, J.F.; Watanabe, H.; Wu, Y.-L.; Zielinski, M.; Ball, D.; et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revision of the N Descriptors in the Forthcoming 8th Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, W.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.; Lee, C.-T.; Chung, J.-H.; et al. Application of N Descriptors Proposed by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer in Clinical Staging. Radiology 2021, 300, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusch, V.W.; Asamura, H.; Watanabe, H.; Giroux, D.J.; Rami-Porta, R.; Goldstraw, P. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: A proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B. Narrative review of patterns of lymphatic drainage in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. AME Med. J. 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Fidias, P.; Hayman, L.A.; Loomis, S.L.; Taber, K.H.; Aquino, S.L. Patterns of lymphadenopathy in thoracic malignancies. RadioGraphics 2004, 24, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Han, Y.; Gao, M.; Su, X.; Liu, Q. Role of skip N2 lymph node metastasis for patients with the stage III-N2 lung adenocarcinoma: A propensity score matching analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, Y.; Han, C.; Gong, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Chong, Y.; Liang, N.; Li, S. Metastatic Patterns of Mediastinal Lymph Nodes in Small-Size Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (T1b). Front. Surg. 2020, 7, 580203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deng, H.Y.; Zeng, M.; Li, G.; Alai, G.; Luo, J.; Liu, L.X.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, Y.D. Lung Adenocarcinoma has a Higher Risk of Lymph Node Metastasis than Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. World J. Surg. 2019, 43, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, J.; Huang, W.; Cheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Pu, Q.; Reticker-Flynn, N.E.; Liu, L. Skip metastasis in mediastinal lymph node is a favorable prognostic factor in N2 lung cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martinez-Zayas, G.; Almeida, F.A.; Simoff, M.J.; Yarmus, L.; Molina, S.; Young, B.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Sagar, A.-E.S.; Gildea, T.; Debiane, L.G.; et al. A Prediction Model to Help with Oncologic Mediastinal Evaluation for Radiation: HOMER. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aziz, F. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: A concise review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2012, 1, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Annema, J.T.; van Meerbeeck, J.P.; Rintoul, R.C.; Dooms, C.; Deschepper, E.; Dekkers, O.M.; De Leyn, P.; Braun, J.; Carroll, N.R.; Praet, M.; et al. Mediastinoscopy vs endosonography for mediastinal nodal staging of lung cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA 2010, 304, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharples, L.D.; Jackson, C.; Wheaton, E.; Griffith, G.; Annema, J.T.; Dooms, C.; Tournoy, K.G.; Deschepper, E.; Hughes, V.; Magee, L.; et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound relative to surgical staging in potentially resectable lung cancer: Results from the ASTER randomised controlled trial. Health Technol. Assess. 2012, 16, 1–75, iii–iv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, P.; Zhao, Y.-Z.; Jiang, L.-Y.; Zhang, W.; Xin, Y.; Han, B.-H. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, F.; Aoe, M.; Ohsaki, Y.; Okada, Y.; Sasada, S.; Sato, S.; Suzuki, E.; Semba, H.; Fukuoka, K.; Fujino, S.; et al. Complications associated with endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: A nationwide survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy. Respir. Res. 2013, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gilbert, C.R.; Dust, C.; Argento, A.C.; Feller-Kopman, D.; Gonzalez, A.V.; Herth, F.; Iaccarino, J.M.; Illei, P.; O’Neil, K.; Pastis, N.; et al. Acquisition and Handling of Endobronchial Ultrasound Transbronchial Needle Samples: An American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Chest 2025, 167, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oki, M.; Saka, H.; Kitagawa, C.; Kogure, Y.; Murata, N.; Ichihara, S.; Moritani, S.; Ando, M. Randomized Study of 21-gauge Versus 22-gauge Endobronchial Ultrasound-guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration Needles for Sampling Histology Specimens. J. Bronchol. Interv. Pulmonol. 2011, 18, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, C.; Darwiche, K.; Franzen, D.; Hager, T.; Bode-Lesnievska, B.; Kneuertz, P.J.; He, K.; Koenig, M.; Freitag, L.; Wei, L.; et al. A Prospective, Randomized Trial for the Comparison of 19-G and 22-G Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Aspiration Needles; Introducing a Novel End Point of Sample Weight Corrected for Blood Content. Clin. Lung Cancer 2019, 20, e265–e273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahidi, M.M.; Herth, F.; Yasufuku, K.; Shepherd, R.W.; Yarmus, L.; Chawla, M.; Lamb, C.; Casey, K.R.; Patel, S.; Silvestri, G.A.; et al. Technical Aspects of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016, 149, 816–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.J.; Chan, H.P.; Soon, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.; A Soo, R.; Kee, A.C.L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the adequacy of endobronchial ultrasound transbronchial needle aspiration for next-generation sequencing in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2022, 166, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, G.A.; Gonzalez, A.V.; Jantz, M.A.; Margolis, M.L.; Gould, M.K.; Tanoue, L.T.; Harris, L.J.; Detterbeck, F.C. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013, 143 (Suppl. S5), e211S–e250S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Olivé, I.; Monsó, E.; Andreo, F.; Sanz, J.; Castellà, E.; Llatjós, M.; de Miguel, E.; Astudillo, J. Sensitivity of linear endobronchial ultrasonography and guided transbronchial needle aspiration for the identification of nodal metastasis in lung cancer staging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2009, 35, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousema, J.E.; van Dorp, M.; Noyez, V.J.; Dijkgraaf, M.G.; Annema, J.T.; van den Broek, F.J.C. Unforeseen N2 Disease after Negative Endosonography Findings with or without Confirmatory Mediastinoscopy in Resectable Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botana-Rial, M.; Lojo-Rodríguez, I.; Leiro-Fernández, V.; Ramos-Hernández, C.; González-Montaos, A.; Pazos-Area, L.; Núñez-Delgado, M.; Fernández-Villar, A. Is the diagnostic yield of mediastinal lymph node cryobiopsy (cryoEBUS) better for diagnosing mediastinal node involvement compared to endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA)? A systematic review. Respir. Med. 2023, 218, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, L.; Tsao, M.S. Tumour tissue sampling for lung cancer management in the era of personalised therapy: What is good enough for molecular testing? Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonuguntla, H.K.; Shah, M.; Gupta, N.; Agrawal, S.; Poletti, V.; Nacheli, G.C. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial cryo-nodal biopsy: A novel approach for mediastinal lymph node sampling. Respirol. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e00808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, J.-R.; Huang, Z.-S.; Fu, W.-L.; Wu, X.-L.; Wu, N.; Kuebler, W.M.; Herth, F.J.; Fan, Y. Transbronchial mediastinal cryobiopsy in the diagnosis of mediastinal lesions: A randomised trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salih Makawi, M.; Ciaccio, S.; Khan, A.; Nathani, A.; Ortiz-Pacheco, R. Lymphatic Spread of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Patterns, Staging, and Diagnosis. Lymphatics 2025, 3, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040043

Salih Makawi M, Ciaccio S, Khan A, Nathani A, Ortiz-Pacheco R. Lymphatic Spread of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Patterns, Staging, and Diagnosis. Lymphatics. 2025; 3(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalih Makawi, Mohamed, Stephen Ciaccio, Asad Khan, Alireza Nathani, and Ronaldo Ortiz-Pacheco. 2025. "Lymphatic Spread of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Patterns, Staging, and Diagnosis" Lymphatics 3, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040043

APA StyleSalih Makawi, M., Ciaccio, S., Khan, A., Nathani, A., & Ortiz-Pacheco, R. (2025). Lymphatic Spread of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Mechanisms, Patterns, Staging, and Diagnosis. Lymphatics, 3(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040043