Indocyanine Green-Guided Lymphatic Sparing Surgery for Lipedema: A Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

2.1. Method

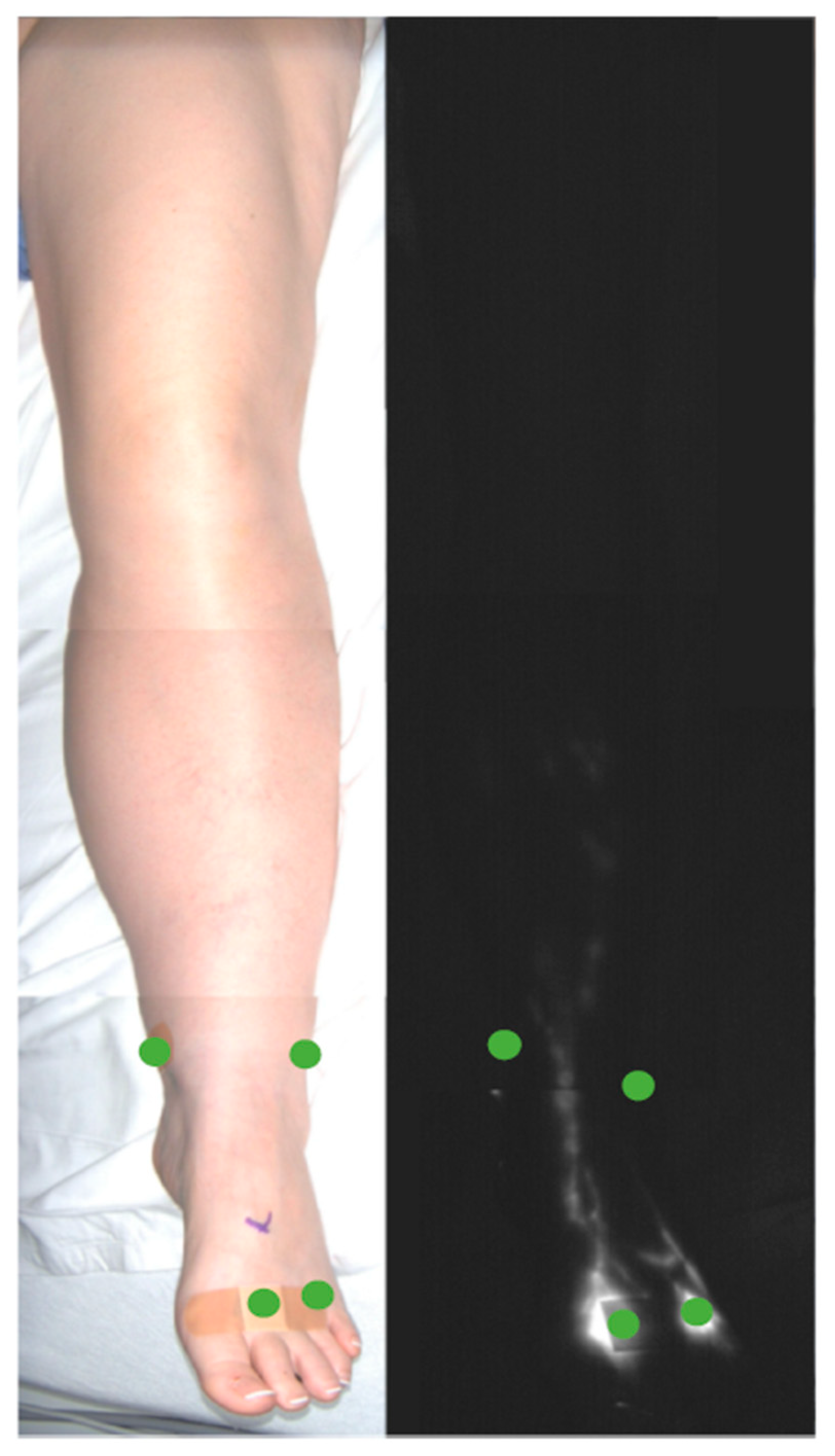

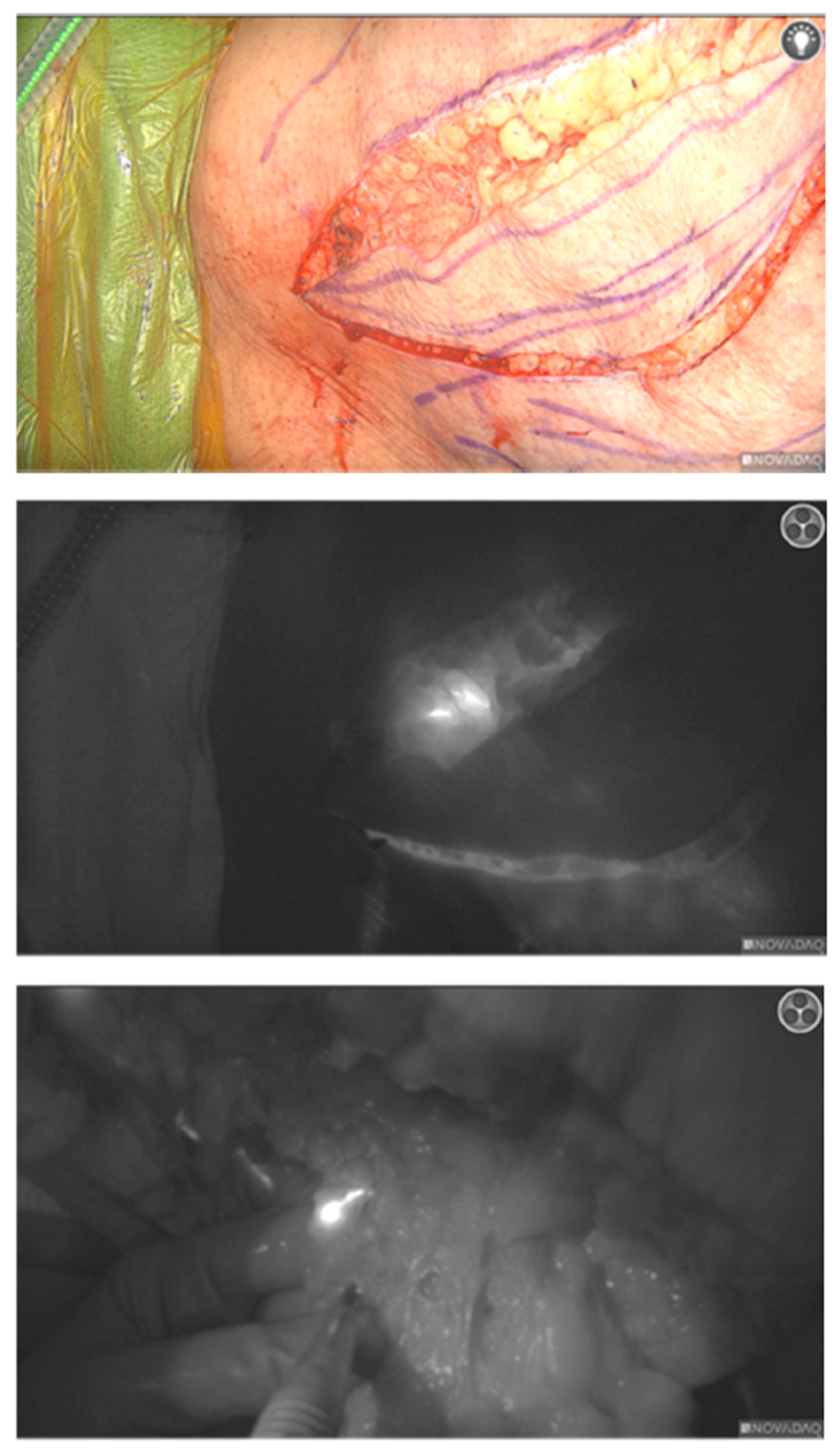

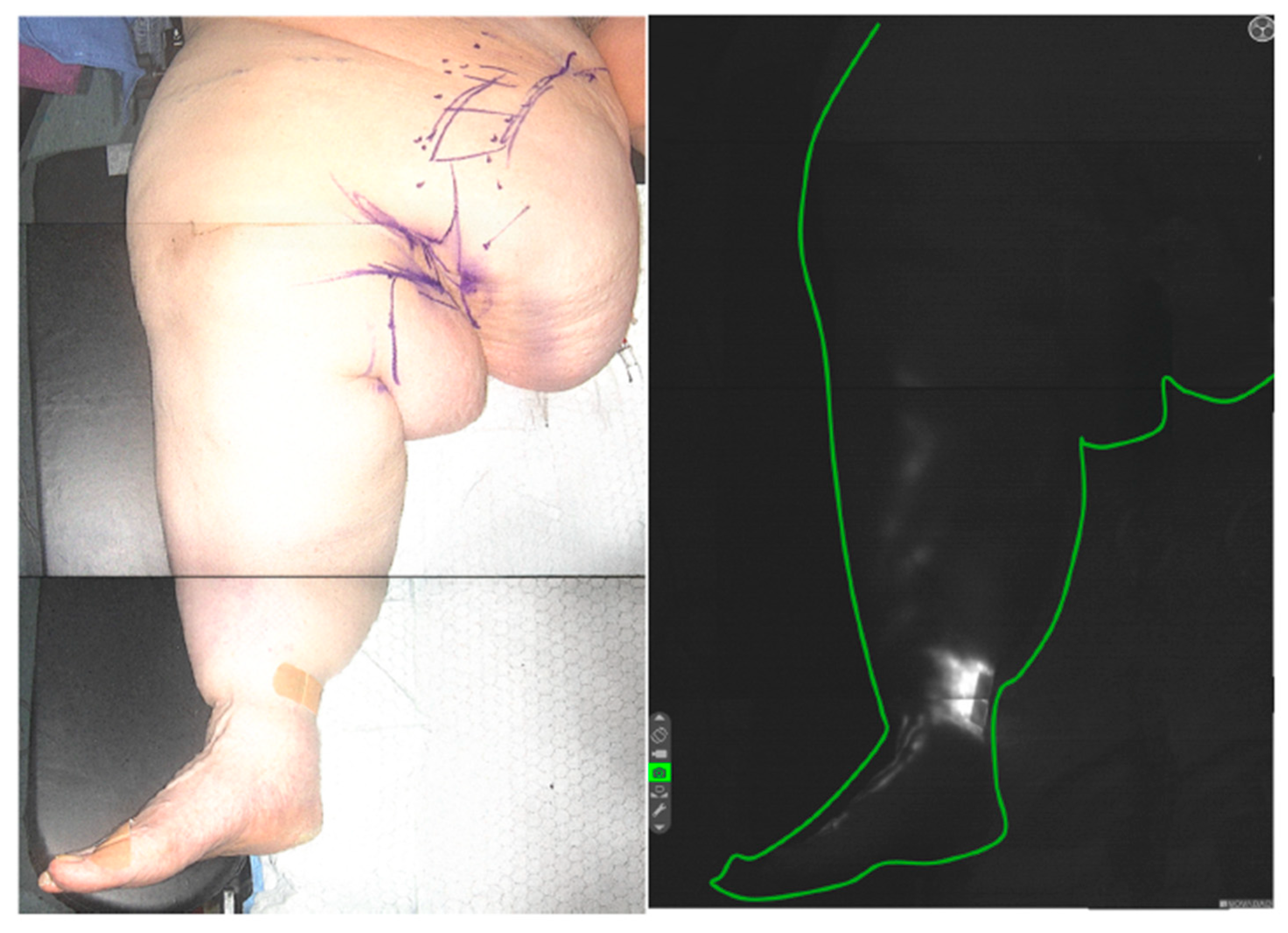

ICG Lymphography

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wold, L.E.; Hines, E.A.; Allen, E.V. Lipedema of the legs; a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann. Intern. Med. 1951, 34, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buso, G.; Depairon, M.; Tomson, D.; Raffoul, W.; Vettor, R.; Mazzolai, L. Lipedema: A Call to Action! Obesity 2019, 27, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, H.; Thompson, B.M.; Suami, H.; Heydon-White, A.; Blackwell, R.; Tisdall Blake, F.; Koelmeyer, L.A. Differentiation of lipoedema from bilateral lower limb lymphoedema by imaging assessment of indocyanine green lymphography. Clin. Obes. 2023, 13, e12588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macca, L.; Di Bartolomeo, L.; Guarneri, C. Cobblestone-like Skin. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2022, 12, e2022200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneri, C.; Vaccaro, M. Cobblestone-like skin. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 179, 673–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshomer, F.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y.; Hong, D.W.; Pak, C.J.; Suh, H.P.; Hong, J.P. Lipedema associated with Skin Hypoperfusion and Ulceration: Soft Tissue Debulking Improving Skin Perfusion. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2024, 51, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamatschek, M.; Knors, H.; Klietz, M.L.; Wiebringhaus, P.; Aitzetmueller, M.; Hirsch, T.; Kueckelhaus, M. Characteristics and Patient Reported Outcome Measures in Lipedema Patients-Establishing a Baseline for Treatment Evaluation in a High-Volume Center. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.F.; Pandey, S.K.; Lensing, J.N. Does Liposuction for Lymphedema Worsen Lymphatic Injury? Lymphology 2023, 56, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, J.M.; Alonso-Farto, J.C. Indocyanine green-guided liposuction for patients presenting with residual nonpitting edema after lymphovenous anastomosis. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS 2022, 75, 2482–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollina, U.; Heinig, B. Treatment of lipedema by low-volume micro-cannular liposuction in tumescent anesthesia: Results in 111 patients. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeller, W.; Hueppe, M.; Meier-Vollrath, I. Tumescent liposuction in lipoedema yields good long-term results. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeller, W.; Meier-Vollrath, I. Tumescent Liposuction: A New and Successful Therapy for Lipedema. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2006, 10, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersant, B.; de Clermont-Tonnerre, E.; Argentino, G.; Bensid, M.; Bensaid, S.; Roccaro, G.; Hermeziu, O.; Murante, A.; La Padula, S.; Meningaud, J.P. Ultrasound Assisted Liposuction with VASER for lower limb lipedema: A single-center cohort of 191 female patients. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 10–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van la Parra, R.F.D.; Deconinck, C.; Pirson, G.; Servaes, M.; Fosseprez, P. Lipedema: What we don’t know. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. JPRAS 2023, 84, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.; Daniel, T. Validation of the Lymphedema Life Impact Scale (LLIS): A condition-specific measurement tool for persons with lymphedema. Lymphology 2015, 48, 128–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.N.; Fertmann, J.P.; Baumeister, R.G.H.; Putz, R.; Frick, A. Tumescent and dry liposuction of lower extremities: Differences in lymph vessel injury. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 718–724, discussion 725–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pas, C.B.; Boonen, R.S.; Stevens, S.; Willemsen, S.; Valkema, R.; Neumann, M. Does tumescent liposuction damage the lymph vessels in lipoedema patients? Phlebology 2020, 35, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro, V.; Gianfranco, M.C.; Cervelli, V.; Gentile, P. Medial Thigh Contouring in Massive Weight Loss: A Liposuction-Assisted Medial Thigh Lift. World J. Plast. Surg. 2019, 8, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenoff, J.A.; Coon, D.; Nayar, H.; Kling, R.E.; Rubin, J.P. Medial Thigh Lift in the Massive Weight Loss Population: Outcomes and Complications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElKiran, Y.M.; ElShafei, A.; Morshed, A.M.; Elkiran, Y.Y.; Elmetwally, A.M. Hybrid approach of massive lipolymphedema of the thigh: A novel surgical technique. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2024, 13, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, H.; Arnold, C.A.; Payne, J.E.; Miller, M.J.; Skoracki, R.J.; Iwenofu, O.H. Massive localized lymphedema: A clinicopathologic study of 46 patients with an enrichment for multiplicity. Mod. Pathol. 2016, 29, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciudad, P.; Bustos, V.P.; Escandón, J.M.; Flaherty, E.G.; Mayer, H.F.; Manrique, O.J. Outcomes of liposuction techniques for management of lipedema: A case series and narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2024, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, K.; Tadisina, K.K.; Brewer, M.; Holton, L.H.; Banda, A.K.; Singh, D.P. Massive localized lymphedema revisited: A quickly rising complication of the obesity epidemic. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2015, 74, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, V.N.; Hinson, C.S.; Hu, M.; Brooks, R.M. Management of Lipedema Beyond Liposuction: A Case Study. Aesthetic Surg. J. Open Forum 2023, 5, ojad088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lipedema Type | Type I | Accumulation of adipose tissue around the hips and buttocks. |

| Type II | Accumulation of adipose tissue spanning from the hips to the knees. | |

| Type III | Accumulation of adipose tissue with a hip-to-ankle phenotype. | |

| Type IV | Accumulation of adipose tissue with a hip-to-ankle phenotype. | |

| Type V | Predominance of fat exclusively in the calf region. | |

| Lipedema Stage | Stage I | Thickening and softening of the subcutis with small nodules; skin is smooth. |

| Stage II | Thickening and softening of the subcutis with larger nodules due to increased fibrous tissue; skin texture is uneven (‘mattress phenomenon’). | |

| Stage III | Thickening and hardening of the subcutis with large nodules; disfiguring lobules of fat on the inner thighs and inner aspects of the knees/over-hanging masses of tissue. | |

| Stage IV | Lipolymphedema. |

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD (Range) |

|---|---|

| Age at time of surgery (years) | 49.5 ± 14.4 (33–70) |

| Preoperative BMI, median, kg/m2 | 52.65 (IQR, 5.68 kg/m2) |

| Comorbidities | Number of patients (%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (25%) |

| Hypertension | 4 (50%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 3 (37.5%) |

| Lipedema type | Number (%) |

| Type I | 2 (0%) |

| Type II | 2 (66.7%) |

| Type III | 3 (33.3%) |

| Type IV | 1 (0%) |

| Type V | 0 (0%) |

| Lipedema stage | Number (%) |

| Stage I | 2 (16.7%) |

| Stage II | 2 (33.3%) |

| Stage III | 3 (50.0%) |

| Stage IV | 1 (0%) |

| Preoperative LLIS score, average | 48 |

| Postoperative LLIS score, average | 18 |

| Complications | Number of patients (%) |

| Superficial skin infection | 2 (25%) |

| Wound dehiscence | 1 (12.5%) |

| Skin necrosis | 0 (0%) |

| Hematoma | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazarei, M.; Sarrami, S.M.; Fadavi, D.; Mehta, M.; Bazell, A.; De La Cruz, C. Indocyanine Green-Guided Lymphatic Sparing Surgery for Lipedema: A Case Series. Lymphatics 2025, 3, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040042

Mazarei M, Sarrami SM, Fadavi D, Mehta M, Bazell A, De La Cruz C. Indocyanine Green-Guided Lymphatic Sparing Surgery for Lipedema: A Case Series. Lymphatics. 2025; 3(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazarei, Michael, Shayan Mohammad Sarrami, Darya Fadavi, Meeti Mehta, Anna Bazell, and Carolyn De La Cruz. 2025. "Indocyanine Green-Guided Lymphatic Sparing Surgery for Lipedema: A Case Series" Lymphatics 3, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040042

APA StyleMazarei, M., Sarrami, S. M., Fadavi, D., Mehta, M., Bazell, A., & De La Cruz, C. (2025). Indocyanine Green-Guided Lymphatic Sparing Surgery for Lipedema: A Case Series. Lymphatics, 3(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040042