Pesticides and Eroding Food Citizenship: Understanding Individuals’ Perspectives on the Greek Food System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Thematic Analysis Results

3.2.1. Theme No 1—Crisis of Confidence in the Food System Governance

3.2.2. Theme No 2—Experiences of Uncertainty Regarding Food Risks

3.2.3. Theme No 3—Deficit of Confidence in Food System Actors

3.2.4. Theme No 4—Perceived Disempowerment Within the Food System

3.2.5. Theme No 5—Demands for Food System Transparency

3.2.6. Theme No 6—Concerns About Food System Sustainability and Integrity

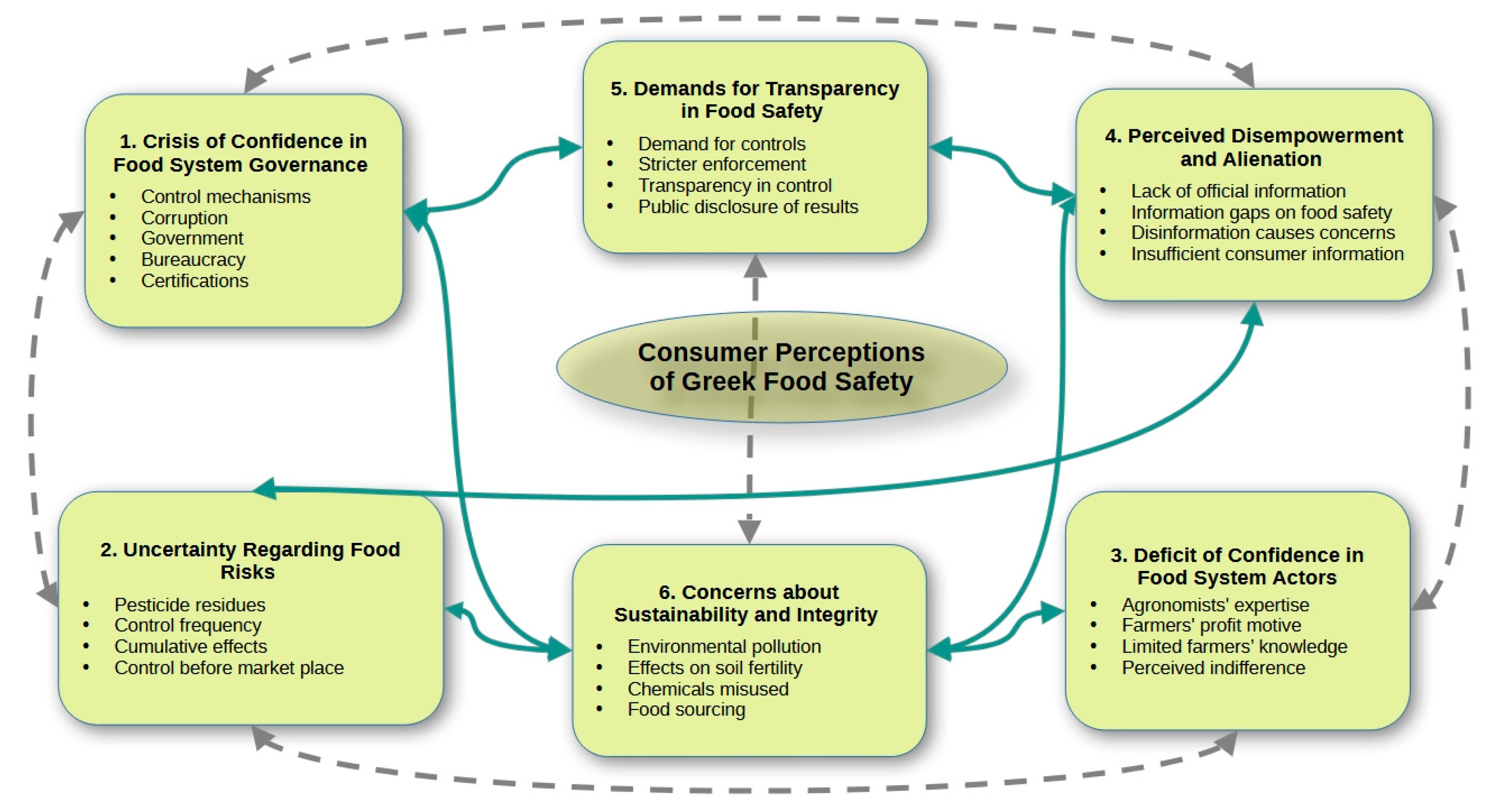

3.3. Interactions Between Themes

4. Discussion

4.1. Implementations: Strategies for Strengthening the Greek Food System

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 581 | 43.3% |

| Male | 443 | 56.7% | |

| Age | 18–24 | 67 | 6.5% |

| 25–34 | 59 | 5.8% | |

| 35–44 | 158 | 15.4% | |

| 45–54 | 428 | 41.8% | |

| 55–64 | 264 | 25.8% | |

| ≥65 | 48 | 4.7% | |

| Educational background | Less than high school | 3 | 0.3% |

| High school—Technical education | 143 | 14.0% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 383 | 37.4% | |

| Master’s degree | 402 | 39.2% | |

| Doctoral degree | 91 | 8.9% | |

| Population of place of residence | Rural area (<2000 residents) | 100 | 9.8% |

| Semi-urban area (2000–10,000 residents) | 139 | 13.6% | |

| Urban area (>10,000 residents) | 785 | 76.6% | |

| Residential geographical area | Northern Greece | 384 | 37.5% |

| Central Greece | 407 | 39.7% | |

| Southern Greece | 233 | 22.8% | |

| Minor children in the family | No | 575 | 56.2% |

| Yes | 449 | 43.8% | |

| Smoking attitude | No | 803 | 78.4% |

| Yes | 221 | 21.6% | |

| Sports activity | Never | 124 | 12.1% |

| Rarely | 305 | 29.8% | |

| Often | 199 | 19.4% | |

| Habitually | 396 | 38.7% | |

| Vegetarians by conviction | No | 988 | 96.5% |

| Yes | 36 | 3.5% | |

| Pesticide users | No | 709 | 69.2% |

| Yes | 315 | 30.8% |

References

- McGregor, J. Public Interests and the Duty of Food Citizenship. In Citizenship and Immigration—Borders, Migration and Political Membership in a Global Age; Cudd, A.E., Lee, W., Eds.; AMINTAPHIL: The Philosophical Foundations of Law and Justice; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 6, pp. 71–88. ISBN 978-3-319-32785-3. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolopoulou-Stamati, P.; Maipas, S.; Kotampasi, C.; Stamatis, P.; Hens, L. Chemical Pesticides and Human Health: The Urgent Need for a New Concept in Agriculture. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, D.; Cely-Santos, M.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Babin, N.; Bernhart, A.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Blesh, J.; Bowness, E.; Feldman, M.; Gonçalves, A.L.; et al. Food Sovereignty and Rights-Based Approaches Strengthen Food Security and Nutrition Across the Globe: A Systematic Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 686492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L.; Belliggiano, A. A Highly Condensed Social Fact: Food Citizenship, Individual Responsibility, and Social Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, J.; Pető, K.; Nagy, J. Pesticide Productivity and Food Security. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Food Safety in the EU: Report; Special Eurobarometer—March 2022; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2022; Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2022-09/EB97.2-food-safety-in-the-EU_report.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Reiss, R.; Johnston, J.; Tucker, K.; DeSesso, J.M.; Keen, C.L. Estimation of Cancer Risks and Benefits Associated with a Potential Increased Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 4421–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcke, M.; Bourgault, M.-H.; Rochette, L.; Normandin, L.; Samuel, O.; Belleville, D.; Blanchet, C.; Phaneuf, D. Human Health Risk Assessment on the Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables Containing Residual Pesticides: A Cancer and Non-Cancer Risk/Benefit Perspective. Environ. Int. 2017, 108, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Insausti, H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Lee, D.H.; Wang, S.; Hart, J.E.; Mínguez-Alarcón, L.; Laden, F.; Ardisson Korat, A.V.; Birmann, B.; Heather Eliassen, A.; et al. Intake of Fruits and Vegetables by Pesticide Residue Status in Relation to Cancer Risk. Environ. Int. 2021, 156, 106744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Total Cancer and All-Cause Mortality—A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, K.D. Public Perceptions of Food-Related Risks: A Cross-National Investigation of Individual and Contextual Influences. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Nikolic, A.; Mujcinovic, A.; Blazic, M.; Herljevic, D.; Goel, G.; Trafiałek, J.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Guiné, R.; Gonçalves, J.C.; et al. How Do Consumers Perceive Food Safety Risks?—Results from a Multi-Country Survey. Food Control 2022, 142, 109216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanzi, L.; Ahmadi Kaliji, S.; Prosperi, P.; Collewet, L.; El Khechen, R.; Michailidis, A.C.; Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; De Rosa, M.; Francescone, M. Value Seeking, Health-Conscious or Sustainability-Concerned? Profiling Fruit and Vegetable Consumers in Euro-Mediterranean Countries. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K.B.; Skarpa, P.E.; Roditakis, E. Pesticide Safety in Greek Plant Foods from the Consumer Perspective: The Importance of Reliable Information. Agrochemicals 2023, 2, 484–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembischevski, P.; Lauria, V.B.D.M.; Da Silva Mota, L.I.; Caldas, E.D. Risk Perception of Food Chemicals and Technologies in the Midwest of Brazil: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Food Control 2022, 135, 108808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, M.-C.; Weinrich, R. Consumer Segmentation for Pesticide-Free Food Products in Germany. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoglou, K.; Roditakis, E. Pesticides and Integrated Crop Management food products: Factors affecting their acceptance by consumers. Entomol. Hell. 2023, 32, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Siegrist, M.; Keller, C. Attitudes toward Chemicals Are Associated with Preference for Natural Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, I.; Feng, Z.; Avanasi, R.; Brain, R.A.; Prosperi, M.; Bian, J. Evaluating the Perceptions of Pesticide Use, Safety, and Regulation and Identifying Common Pesticide-related Topics on Twitter. Integr. Envir. Assess Manag. 2023, 19, 1581–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C.; Sarwar, A.; Khan, N. The Effects of Consumer Consciousness, Food Safety Concern and Healthy Lifestyle on Attitudes toward Eating “Green”. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, B.K.; Lobo, A.; Vu, P.A. Organic Food Purchases in an Emerging Market: The Influence of Consumers’ Personal Factors and Green Marketing Practices of Food Stores. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembischevski, P.; Caldas, E.D. Consumers’ Trust in Different Sources of Information Related to Food Hazards and Their Judgment of Government Performance—A Cross-Sectional Study in Brazil. Foods 2023, 12, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Clark, B.; Rhymer, C.; Kuznesof, S.; Hajslova, J.; Tomaniova, M.; Brereton, P.; Frewer, L. A Systematic Review of Consumer Perceptions of Food Fraud and Authenticity: A European Perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 94, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkos, D.; Kosma, I.S.; Vasiliou, A.; Guine, R.P.F. Consumers’ Trust in Greek Traditional Foods in the Post COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, R.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Golba, J.; Nowacka, A.; Hołodyńska-Kulas, A.; Kopczyńska, K.; Góralska-Walczak, R.; Gnusowski, B. Evaluation of Pesticide Residues Occurrence in Random Samples of Organic Fruits and Vegetables Marketed in Poland. Foods 2022, 11, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blok, A.; Jensen, M.; Kaltoft, P. Regulating Pesticide Risks in Denmark: Expert and Lay Perspectives. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2006, 8, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Schebesta, H.; Candel, J.J.L. Game-Changing Potential of the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 586–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyabina, V.P.; Esimbekova, E.N.; Kopylova, K.V.; Kratasyuk, V.A. Pesticides: Formulants, Distribution Pathways and Effects on Human Health—A Review. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabro, G.; Vieri, S. Limits and Potential of Organic Farming towards a More Sustainable European Agri-Food System. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Thorsøe, M.H. Rebalance Power and Strengthen Farmers’ Position in the EU Food System? A CDA of the Farm to Fork Strategy. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 41, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, W.; Gao, J. Do Not Be Anticlimactic: Farmers’ Behavior in the Sustainable Application of Green Agricultural Technology—A Perceived Value and Government Support Perspective. Agriculture 2023, 13, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Messina, F. Attitudes towards Organic Foods and Risk/Benefit Perception Associated with Pesticides. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.J.; Warland, R. Determinants of Food Safety Risks: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach*. Rural Soc. 2005, 70, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.R.D.; Hammitt, J.K. Perceived Risks of Conventional and Organic Produce: Pesticides, Pathogens, and Natural Toxins. Risk Anal. 2001, 21, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kleef, E.; Ueland, Ø.; Theodoridis, G.; Rowe, G.; Pfenning, U.; Houghton, J.; Van Dijk, H.; Chryssochoidis, G.; Frewer, L. Food Risk Management Quality: Consumer Evaluations of Past and Emerging Food Safety Incidents. Health Risk Soc. 2009, 11, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, A.P.G.; Favaro, B.F.; De Oliveira, A.S.; Zanin, L.M.; Da Cunha, D.T. The Role of Risk Perception as a Competitive Mediator of Trust and Purchase Intention for Vegetables Produced with Pesticides. Food Control 2024, 160, 110351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.E.; Marques, J.M.R.; Torres, A.P.; Marshall, M.I.; Deering, A.J. Safe, Sustainable, and Nutritious Food Labels: A Market Segmentation of Fresh Vegetables Consumers. Food Control 2024, 165, 110654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Cvetkovich, G. Perception of Hazards: The Role of Social Trust and Knowledge. Risk Anal. 2000, 20, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfman, N.C.; Vázquez, E.L.; Dorantes, G. An Empirical Study for the Direct and Indirect Links between Trust in Regulatory Institutions and Acceptability of Hazards. Safety Sci. 2009, 47, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjærnes, U.; Harvey, M.; Warde, A. Trust in Food: A Comparative and Institutional Analysis; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4039-9891-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pauer, S.; Rutjens, B.T.; Brick, C.; Lob, A.B.; Buttlar, B.; Noordewier, M.K.; Schneider, I.K.; Van Harreveld, F. Is the Effect of Trust on Risk Perceptions a Matter of Knowledge, Control, and Time? An Extension and Direct-Replication Attempt of Siegrist and Cvetkovich (2000). Social Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2024, 15, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, Z.; Liu, Y.; William, S. Trust in Government, Perceived Integrity and Food Safety Protective Behavior: The Mediating Role of Risk Perception. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1605432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M. Trust and Risk Perception: A Critical Review of the Literature. Risk Anal. 2021, 41, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitlin, J.; Van Der Duin, D.; Kuhn, T.; Weimer, M.; Jensen, M.D. Governance Reforms and Public Acceptance of Regulatory Decisions: Cross-national Evidence from Linked Survey Experiments on Pesticides Authorization in the European Union. Regul. Gov. 2023, 17, 980–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Cabedo, C.; Gómez-Benito, C. A Theoretical Model of Food Citizenship for the Analysis of Social Praxis. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2017, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, J.L. Eating Right Here: Moving from Consumer to Food Citizen: 2004 Presidential Address to the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society, Hyde Park, New York, June 11, 2004. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore; Washington, DC, USA; Melbourne, Australia, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4739-5324-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen, K.J. An Invitation to Social Construction: Co-Creating the Future, 4th ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-5297-7779-6. [Google Scholar]

- De Tavernier, J. Food Citizenship: Is There a Duty for Responsible Consumption? J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2012, 25, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escajedo San-Epifanio, L. Challenging Food Governance Models: Analyzing the Food Citizen and the Emerging Food Constitutionalism from an EU Perspective. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.J.; Ma, L. Citizen Participation, Perceived Public Service Performance, and Trust in Government: Evidence from Health Policy Reforms in Hong Kong. Public Perform. Manag. 2021, 44, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, J.; Gillespie, S.; Savona, N.; Deeney, M.; Kadiyala, S. Trust and Responsibility in Food Systems Transformation. Engaging with Big Food: Marriage or Mirage? BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e007350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D. The Philosophical Foundations of Constructionist Research. In Handbook of Constructionist Research; Holstein, J.A., Gubrium, J.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-59385-305-1. [Google Scholar]

- Loseke, D.R.; Kusenbach, M. The Social Construction of Emotion. In Handbook of Constructionist Research; Holstein, J.A., Gubrium, J.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-59385-305-1. [Google Scholar]

- Krystallis, A.; Frewer, L.; Rowe, G.; Houghton, J.; Kehagia, O.; Perrea, T. A Perceptual Divide? Consumer and Expert Attitudes to Food Risk Management in Europe. Health Risk Soc. 2007, 9, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, E.; Houghton, J.R.; Krystallis, A.; Pfenning, U.; Rowe, G.; Van Dijk, H.; Van Der Lans, I.A.; Frewer, L.J. Consumer Evaluations of Food Risk Management Quality in Europe. Risk Anal. 2007, 27, 1565–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.; Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; Elliott, C.; Dean, M. Assessing Differences in Levels of Food Trust between European Countries. Food Control 2021, 120, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergen, K.J.; Gergen, M.M. Social Construction and Research as Action. In The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2nd ed.; Reason, P., Bradbury, H., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4129-2029-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beekman, V. Consumer Rights to Informed Choice on the Food Market. Ethic Theory Moral Prac. 2008, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.-T.; Lin, H.-C.; Tsai, M.-C. Effect of Institutional Trust on Consumers’ Health and Safety Perceptions and Repurchase Intention for Traceable Fresh Food. Foods 2021, 10, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaschi, D.; Leonardi, L. Food Insecurity and Changes in Social Citizenship. A Comparative Study of Rome, Barcelona and Athens. Eur. Soc. 2023, 25, 413–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriflik, L. Consumer Citizenship: Acting to Minimise Environmental Health Risks Related to the Food System. Appetite 2006, 46, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, U. Critical Theory of World Risk Society: A Cosmopolitan Vision. Constellations 2009, 16, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-based Qualitative Analytic Approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward Good Practice in Thematic Analysis: Avoiding Common Problems and Be(Com)Ing a Knowing Researcher. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2023, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Participants’ Crisis of Confidence in Food System Governance | Lack of trust in the credibility and accountability of food system governance |

| 2 | Participants’ Experiences of Uncertainty Regarding Food Risks | Uncertainty and apprehension about food safety and quality risks |

| 3 | Deficit of Confidence in Food System Actors | Questioning of food system stakeholder credibility |

| 4 | Participants’ Disempowerment in the Food System | Perceived disempowerment and alienation within the food provisioning landscape |

| 5 | Participants’ Demands for Food System Transparency | The issue of enhanced transparency in food safety |

| 6 | Concerns about Food System Sustainability and Integrity | Concerns about the long-term viability and ethical soundness of the food production |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simoglou, K.B.; Skarpa, P.E.; Roditakis, E. Pesticides and Eroding Food Citizenship: Understanding Individuals’ Perspectives on the Greek Food System. Agrochemicals 2025, 4, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals4010003

Simoglou KB, Skarpa PE, Roditakis E. Pesticides and Eroding Food Citizenship: Understanding Individuals’ Perspectives on the Greek Food System. Agrochemicals. 2025; 4(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals4010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimoglou, Konstantinos B., Paraskevi El. Skarpa, and Emmanouil Roditakis. 2025. "Pesticides and Eroding Food Citizenship: Understanding Individuals’ Perspectives on the Greek Food System" Agrochemicals 4, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals4010003

APA StyleSimoglou, K. B., Skarpa, P. E., & Roditakis, E. (2025). Pesticides and Eroding Food Citizenship: Understanding Individuals’ Perspectives on the Greek Food System. Agrochemicals, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/agrochemicals4010003