1. Introduction

The Nigerian poultry sector faces significant challenges stemming from inflationary pressures and currency depreciation, which have collectively heightened price volatility and undermined sector stability [

1,

2]. Inflation in Nigeria has been notably volatile following key macroeconomic reforms, including the 2023 removal of fuel subsidies, which triggered sharp increases in energy and transportation costs—primary drivers of poultry production expenses [

3,

4,

5]. Empirical analyses confirm a robust link between energy price fluctuations and inflation, exacerbating costs for agricultural inputs such as feed, and resulting in corresponding increases in poultry product prices [

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, poultry producers have had to raise output prices, perpetuating price instability throughout the sector.

Simultaneously, the depreciation of the Nigerian naira has intensified cost pressures, particularly for imported feed ingredients such as maize and soybeans that form a significant share of production inputs. This currency-induced cost shock has forced poultry farmers to recalibrate operations, often compressing profit margins and causing market exits among smaller, vulnerable enterprises [

9]. These dynamics impede sustainable growth and resilience of small- and medium-scale poultry farms, a critical concern given poultry’s pivotal role in Nigeria’s food security and nutritional landscape [

10,

11]. Agriculture, which is the backbone of Nigeria’s economy and employment, accounting for approximately 70% of national labor, has endured policy neglect since the oil economy’s rise [

12,

13]. Within agriculture, poultry farming stands out, given its nutritional importance and contribution to food security. However, persistent inflation-driven rises in essential inputs, notably feed and veterinary pharmaceuticals, have curtailed profitability and operational sustainability among producers [

14,

15]. For instance, poultry feed accounts for about 70% of production costs; maize prices alone surged by approximately 60% in early 2024, severely undermining profitability and production consistency in the sector [

16,

17].

The nexus of inflation, exchange rate volatility, and poultry price fluctuations generates complex analytical challenges with significant implications for market supply responses and overall stability. Exogenous shocks—including economic recessions and public health crises—further exacerbate sector vulnerability, highlighting the pressing need for effective risk mitigation and policy support [

9,

18]. While government efforts aimed at enhancing input access and market efficiency have yielded some gains, the poultry subsector remains acutely vulnerable to inflation and currency fluctuations [

19]. Rising poultry product prices, driven by these macroeconomic factors, substantially erode household purchasing power, especially among low-income populations dependent on food expenditures—exacerbating food insecurity [

20,

21]. Globally, high food prices have intensified undernourishment and poverty, with [

22,

23] documenting over 700 million undernourished people worldwide.

Exchange rate volatility additionally shapes agricultural value chains by influencing export competitiveness, import costs of capital goods, and domestic investment decisions [

24,

25]. Despite Nigeria’s extensive arable land, persistent food inflation and price rises are partly attributable to import reliance and naira depreciation [

26,

27]. Government initiatives, including the Agricultural Transformation Agenda and Anchor Borrowers Program, aim to bolster food security and curb inflation; however, Nigeria’s food price inflation remains significantly higher than peer African countries, largely due to exchange rate instability damping economic growth and agricultural productivity [

28,

29,

30].

While broad scholarship explores the influence of exchange rates on inflation in Nigeria [

28,

31], limited research examines the specific compounded effects of inflation and exchange rate volatility on poultry price fluctuations—a critical gap this study addresses.

Empirical insights deepen the analytical rigors of this discourse, providing a varied understanding of the propinquity among key variables and offering evidence based implications for research and practice. Using a Structural Vector Autoregressive (SVAR) model, ref. [

26] identify agricultural productivity as a key determinant exerting lasting effects on inflation, where productivity gains initially increase food prices but ultimately support inflation reduction, emphasizing agricultural efficiency’s role in price stabilization. Ref. [

32]’s GARCH-based analyses demonstrate that shocks from consumer price indices, lending rates, and exchange rates—excluding the oil market—drive food price volatility via complex market interdependencies.

Ref. [

29], employing a Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) framework, reveal a robust long-run interplay among exchange rates, food inflation, and GDP, uncovering asymmetric and positive correlations between exchange rate fluctuations and food inflation, coupled with an inverse relationship between inflation and GDP growth. Ref. [

33], adopting exponential GARCH models, highlight persistent and leverage effects in food price returns, noting that exchange rate volatility particularly magnifies imported food price volatility—critical in Nigeria’s import-dependent context.

Ref. [

34] reports positive correlations among exchange rate volatility, exports, imports, and inflation, alongside an inverse association between inflation volatility and economic growth, indicating that moderate inflation fosters investment, while excessive inflation and currency fluctuations hamper development. Ref. [

21] supports these findings through GARCH and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) analyses, identifying money supply and nominal exchange rate fluctuations as significant, long-run inflation drivers, underscoring monetary factors in Nigeria’s inflationary environment.

Recent contributions by [

28] contextualize these dynamics within the aftermath of 2023 policy shocks, including fuel subsidy removal, emphasizing accelerated food price inflation and volatility that disproportionately elevate food insecurity risks for vulnerable populations. This highlights the interplay between exogenous policy shocks and existing structural vulnerabilities in amplifying inflationary pressures.

This study introduces a novel and timely analytical approach to understanding food price instability in Nigeria by integrating inflationary dynamics and exchange rate volatility as joint macroeconomic drivers of poultry price fluctuations. While prior research has separately explored the effects of exchange rate movements or inflation on general food price levels, few studies have systematically examined their combined influence on a specific agricultural subsector as economically and nutritionally critical as poultry. Unlike most earlier works that rely on pre-2023 data and overlook recent structural policy shocks—notably the removal of fuel subsidies and subsequent currency depreciation—this study employs contemporary macroeconomic data reflecting the new price regime and its transmission effects across poultry value chains. By focusing on the post-reform macroeconomic environment, the research captures emerging non-linearities and asymmetries in the relationship between inflation, exchange rate dynamics, and poultry price volatility, which have not been adequately documented in the prior literature. Closing these gaps will support theoretical development on inflation in emerging markets that will allow evidence-based and adaptive intervention to stabilize food prices, agricultural productive output, and economic growth.

Based on existing theoretical and empirical discussion, the present study aimed to provide answers to the following research questions: (1) What is the trend of exchange rate, inflation, and poultry price volatility in Nigeria? (2) Does poultry price volatility exhibit a long-run equilibrium relationship with exchange rate and inflation? (3) Does poultry price volatility have a short-run dynamic relationship with exchange rate and inflation? Consistent with these research questions, the primary objective of the study was to determine the impact of exchange rate and inflation on poultry price volatility in Nigeria. In particular, we sought to do the following: (i) investigate the trend of exchange rate, inflation, and the volatility of poultry price; (ii) establish their long-term relationship; (iii) analyze the short- and long-run dynamics among the variables. Consequently, the study tested the following null hypotheses, namely, (i) poultry price volatility does not have a long-run relationship with exchange rate and inflation in Nigeria; (ii) exchange rate and inflation donot have a short-run effecton poultry price volatility in Nigeria; and (iii) exchange rate and inflation do not have long-run effect on poultry price volatility in Nigeria.

2. Theoretical Background

This study connects the theories of Cost-Push Inflation, Loening’s framework of food prices, and the concept of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), which help it to understand how the macroeconomic situation affects the volatility of poultry prices in Nigeria. Each perspective is designed to serve the four aspects of the study: (i) explaining the dynamics and timescales of volatility in the exchange rate, inflation, and poultry prices; (ii) testing for long-run relationships; (iii) examining the short-run relationships between predictors; and (iv) identifying the transmission channels between exchange rate and inflation affecting volatile poultry prices.

Cost-push theory asserts that inflation can arise from rising costs of production—wages, energy, and raw materials—which reduce aggregate supply and drive up prices. In open economies, such as poultry industries dependent on imports, import price hikes for feed, fuel, and veterinary inputs are rapidly passed on into retail poultry prices [

35]. Exchange rate depreciation increases local currency inputs’ costs, causing cost pressure in the supply chain due to continuous price volatility in value chains relying on foreign material input, which are also evidence from empirical studies. This process is logically related on the one hand toObjectives i and iv, and explains the short-run cost push and the persistence of those cost pushes under rigid input markets, or those dependent on imports.

Ref. [

36] developed a structural model linking domestic supply dynamics, external price pressures, and monetary conditions to explain the movement of food prices in agrarian systems. They are well-suited to the context where domestic shocks (supply shortfalls, logistic bottlenecks) combine with exchangerate-driven imported cost shocks. Loening’s approach therefore provides a formal underpinning for testing long-run cointegration (Objective ii) and short-run adjustment dynamics (Objective iii), since variations in the money and external sectors produce long-lasting and distal impacts on local food prices. The current study of the volatility of food prices corroborates this multi-component view and illustrates how disruptions in supply, the cost of trade with others, and global shocks to commodity prices jointly drive domestic price performance.

PPP theory is rooted in Cassel and was developed by others more recently; it considers the way exchange rates convert foreign prices to domestic currency prices. In an economy where agricultural staples are imported heavily, higher exchange rate movements trigger import inflation, which increases production costs and the volatility in sectoral price levels. More recent work on Nigeria has identified non-linear and threshold effects of exchange rate pass-through to the home currency, and its inflationary implications for domestic prices, inferring that currency shocks can have different time periods in sectors like poultry, conditional on the depreciation regime (small for small scale, large for large scale), and the magnitude of devaluation. PPP thus directly informs empirical modeling of exchangerate effects on PPV and supports Objective (iv) by defining the mechanism of transmission from EXC to domestic poultry prices.

Combined, these theories form a comprehensive theoretical argument: cost-push mechanisms demonstrate how shocks of input cost will cause a rise in poultry market prices; Loening’s structural account places such shocks in context with domestic and external sectors in interaction and encourages cointegration with each other; and PPP/exchangerate pass-through formalizes the external channel through which exchange flows influence domestic costs. This triadic integration specifically underpins the study’s aims: (i) time-series dynamics are analyzed in order to identify immediate vs. lagged response; (ii) long-run equilibrium (cointegration) is examined as a means to discover the systemic links; (iii) short-run ARDL dynamics capture short-run adjustment; and (iv) structural interpretation and policy implications are derived from the identified transmission pathways.

3. Methodology

The study used annual time series obtained from reputable and authoritative secondary sources to ensure accuracy and reliability. Yearly poultry price index (PPI) (2014–2016 = 100) data were sourced from the Food and Agriculture Organisation Statistics (FAOSTAT). Inflation rates were represented by the consumer price index (CPI) (2010 = 100) and exchange rate data, specifically the real effective exchange rate index (2010 = 100) were obtained from the World Development Indicator (WDI). The data spanthe period from 1991 to 2024. The starting period wasdetermined by the availability of poultry price data. The selected variables were chosen based on their relevance tothis study and theoretical linkages.

The collected data underwent rigorous analysis to elucidate the relationships among poultry prices, inflation rates, and exchange rates. Initially, descriptive statistics werecomputed to provide an overview of the data’s central tendencies and dispersions. Subsequently, stationarity tests, such as the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF), and Philip Pirron’s tests, were conducted to determine the presence of unit roots in the time series data. Based on the stationarity results, appropriate econometric models were employed: the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model and its associatedbounds test were used to achieve the objectives. To measure the volatility of poultry price, theGeneralized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) model was applied, allowing for the examination of how fluctuations in inflation and exchange rates influenced poultry price volatility. All analysis were performed in EVIEWS 13.

The GARCH (1,1) model with constant mean is specified as follows:

return series (i.e., log return of poultry price)

= mean return

= the residual (error term) from the mean equation

= the time varying variance of the error term

ω > 0 = constant term

α ≥ 0 = ARCH term (shock from previous period)

β ≥ 0 = GARCH term (volatility persistence)

Stationarity condition: α + β < 1

The conditional variance series was extracted as the measure of poultry price volatility (PPV).

The Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model was introduced by [

37]. It is a popular econometric technique used to analyze the dynamic relationship between a dependent variable and one or more explanatory variable(s) in both the short-run and long-run. ARDL is especially useful for small-sample data and hence provides strong results even when there are different lag lengths for each variable. Some steps involved in making estimates using ARDL included the following:

where

: poultry price volatility (dependent variable)

: food inflation (independent)

: exchange rate (independent)

q, p, r: lag orders

: error term

- 3.

Bound test for cointegration: this is used to check if a long-run relationship exists between poultry price volatility, inflation, and exchange rate. A null hypothesis indicates no long-run relationship, whereas an alternative hypothesis indicates that a long-run relationship exists.

- 4.

Estimate long-run relationships: if the bounds test confirms cointegration, estimate the long-run coefficients. This emphasizes how inflation and exchange rate permanently affects poultry price volatility over time.

- 5.

Estimate

where

: first differences

the lagged error correction term from the long run model

: measures the speed of adjustment. When it is negative, it confirms that poultry price volatility adjusts to restore equilibrium after short-run shocks

- 6.

Diagnostic and stability tests: this is to ensure the model is strong. It includes serial correlation, also known as the Breusch–Godfrey; the heteroskedasticity test, otherwise known as the white or theBreusch–Pagan test; normality test, otherwise known as the Jarque–Bera test, and the stability test, also known as CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots. These tests confirm that your results are reliable and that the model is stable overtime.

The choice of the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model for analyzing the effect of inflation and exchange rate volatility on poultry price volatility is primarily motivated by its methodological flexibility and robustness in dealing with real-world economic data. One of the major advantages of the ARDL approach is that it accommodates variables that are integrated of different orders, that is, a mixture of (I(0)) and (I(1)), as long as none is integrated of order two (I(2)) [

37]. This makes the model particularly suitable for studies involving macroeconomic and agricultural variables, which often display varying degrees of stationarity.

Another justification lies in the model’s ability to capture both

short-run and long-run dynamics within a single framework. In the context of poultry markets, short-run shocks such as sudden exchange rate depreciation or inflation spikes can cause immediate price fluctuations, while long-run effects reflect structural adjustments in input costs and market equilibrium. The ARDL model, through its error correction representation, effectively distinguishes between these short-run adjustments and long-run relationships [

38].

Furthermore, the ARDL model performs well even with

small sample sizes, which is advantageous for agricultural price studies where data availability is often limited [

39].

It also allows for different lag lengths for each variable, providing flexibility to account for the delayed responses typical in agricultural markets where price transmission may not be instantaneous due to production and distribution lags.

In addition, the inclusion of lagged dependent and independent variables helps mitigate

endogeneity and

serial correlation issues, improving the reliability of estimates [

37]. The model’s bounds testing approach to cointegration provides a straightforward statistical means of testing for the existence of a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables without the need for complex pre-testing procedures.

Overall, given the dynamic nature of poultry prices and the influence of macroeconomic factors such as inflation and exchange rate volatility, the ARDL model offers a comprehensive and empirically reliable approach. It enables the estimation of both short-run and long-run effects, making it valuable for understanding market behavior and guiding policy formulation aimed at stabilizing agricultural prices.

Prior to carrying out further econometric estimates, all variables were initially tested for stationarity to mitigate spurious regressions arising from non-stationary time series [

40,

41]. The Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test was also used to account for serial autocorrelation. The estimation of integration orders appeared to vary from I(0) to I(1). According to their findings, both the linear- and Non-Linear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL)-bound tests were estimated, as they take into account variables integrated at I(0), I(1), or a blend of the two [

37,

42]. Cointegration was confirmed by the evidence that the computed F-statistic exceeded the upper-bound critical value for the I(1) level, demonstrating a long-run equilibrium relationship among the variables in the model [

43]. Given that the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is efficient across small sample sizes for small-sample analysis, and in comparison to the Hannan–Quinn, Schwarz, and Final Prediction Error scales [

42,

44], it was used to choose an optimal lag length for analysis. Accordingly, ARDL was the proposed framework to apply, since it provides an effective model of short- and long-run dynamics in systems, when variables have mixed (cointegrated) integration orders. Diagnostic tests were performed to check the estimate’s robustness and reliability. Consequently, this included the ARCH-LM test for heteroscedasticity, the Breusch–Godfrey test for serial correlation, and the Jarque–Bera test for normality, while the stability of the model was performed using the CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Poultry Price Volatility (PPV), Exchange Rate (LEXR), and Inflation (LCPI)

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for poultry price volatility (PPV), exchange rate (LEXR), and inflation (LCPI) in Nigeria from 1995 to 2024. The mean PPV of 0.6546 with a high standard deviation of 1.0714 and positive skewness of 1.7825 indicates that poultry prices were moderately volatile on the average but experienced occasional extreme spikes. LEXR shows a mean of 4.7943 with moderate variation (Std. Dev. = 0.5914) and slight positive skewness, suggesting periods of exchange rate depreciation. Inflation (LCPI) had a mean of 3.1524 and was slightly left-skewed (skewness = −0.45) with lower kurtosis, indicating moderate and more stable fluctuations compared to PPV. The Jarque–Bera tests reveal that PPV and LEXR deviated from normality, while LCPI was approximately normally distributed. Overall, PPV exhibited the highest volatility, highlighting its sensitivity to economic variables like exchange rate and inflation.

4.2. Estimation of GARCH Model of Poultry Price Volatility

The upper panel of

Table 2 presents the estimates of the GARCH(1,1) model of poultry price volatility, while the lower panel presents the Wald test of joint significance of the ARCH and GARCH parameters (i.e., H

0: α = 0, β = 0) in the variance equation. The results verified the non-negativity and stationarity restrictions (α ≥ 0, β ≥ 0,α + β < 1). Further, the Wald statistic confirmed that the volatility parameters are jointly significant at the 5% level, validating the model’s ability to capture conditional heteroskedaticity. The model diagnostics support the robustness of the estimation with moderately strong R

2 (0.421) and an acceptable Durbin–Watson statistic (1.987). These results suggest that the GARCH(1,1) specification is appropriate for modeling poultry price volatility, capturing both the short-term shocks and persistent volatility dynamics.

4.3. Trend of Poultry Price Volatility (PPV), Exchange Rates, and Inflation (1991–2024)

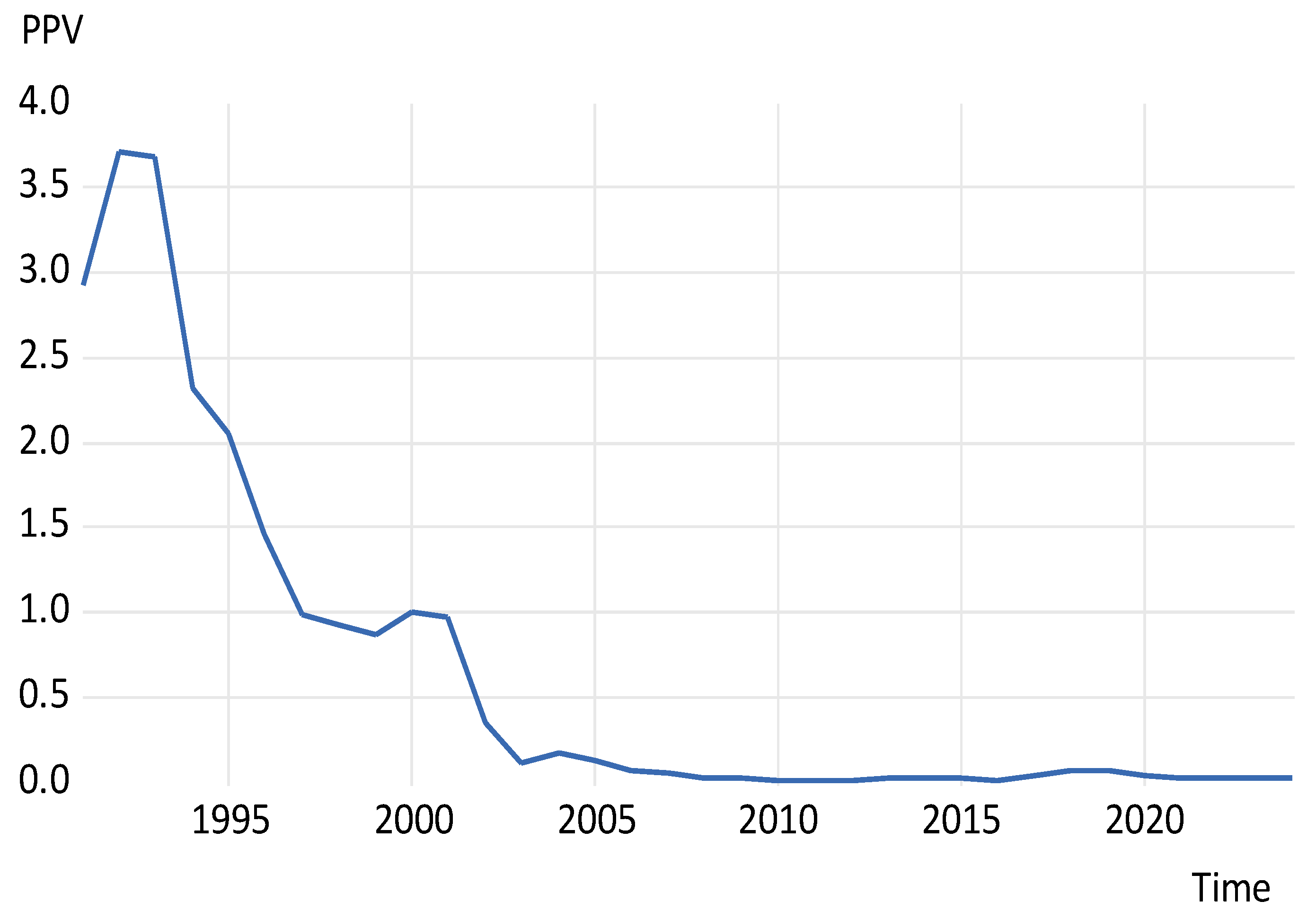

The trend of poultry price volatility (PPV) (

Figure 1) shows that, in 1991, PPV was relatively high at 3, followed by a slight increase up to 1995. From 1995, volatility declined steadily, dropping to 2, then further to 1 by 2000, and reaching almost 0 by 2005. Between 2005 and 2020, PPV remained very low, fluctuating slightly around zero, and continuing this minimal variation beyond 2020. This trend indicates that poultry prices were highly volatile in the early 1990s but stabilized significantly from the mid-2000s onwards, suggesting that structural changes in the market or economic factors may have reduced price fluctuations over time.

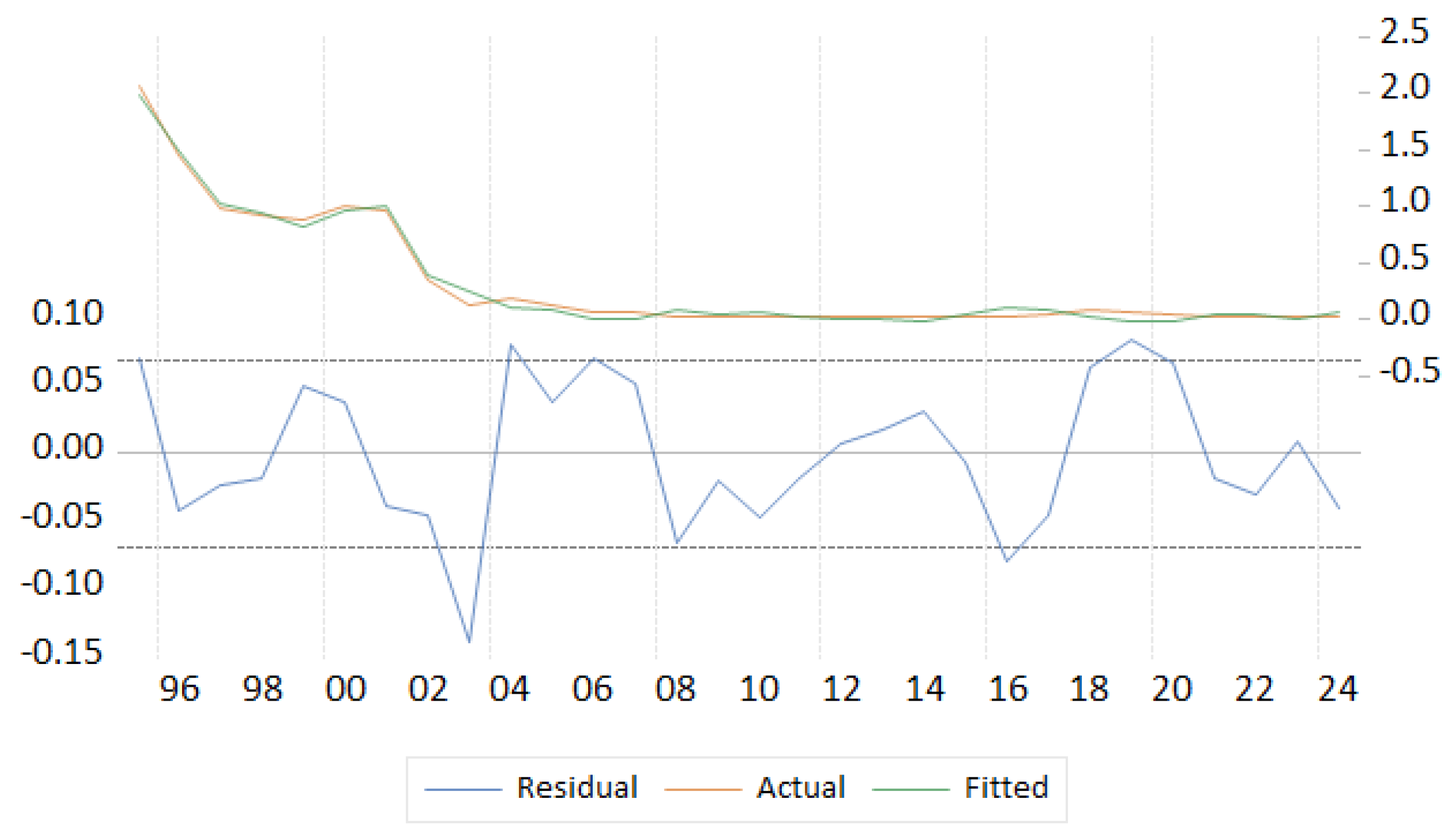

Figure 2 presents the comparison between the observed and fitted poultry price volatility (PPV). The figure shows that the ARDL model adequately captures the overall trend and level of volatility over time. The fitted PPV closely follows the long-run decline in the late 1990s and its stabilization afterwards. As expected with annual data, the short-term fluctuations are not perfectly matched but the fitted series remains within the range of the observed movements. The residual is small, random, and does not show evidence of autocorrelation or structural drift, indicating that the model is well-specified and free of bias and we thus conclude that the model provides a good fit and successfully explains the main macroeconomic drivers of poultry price volatility.

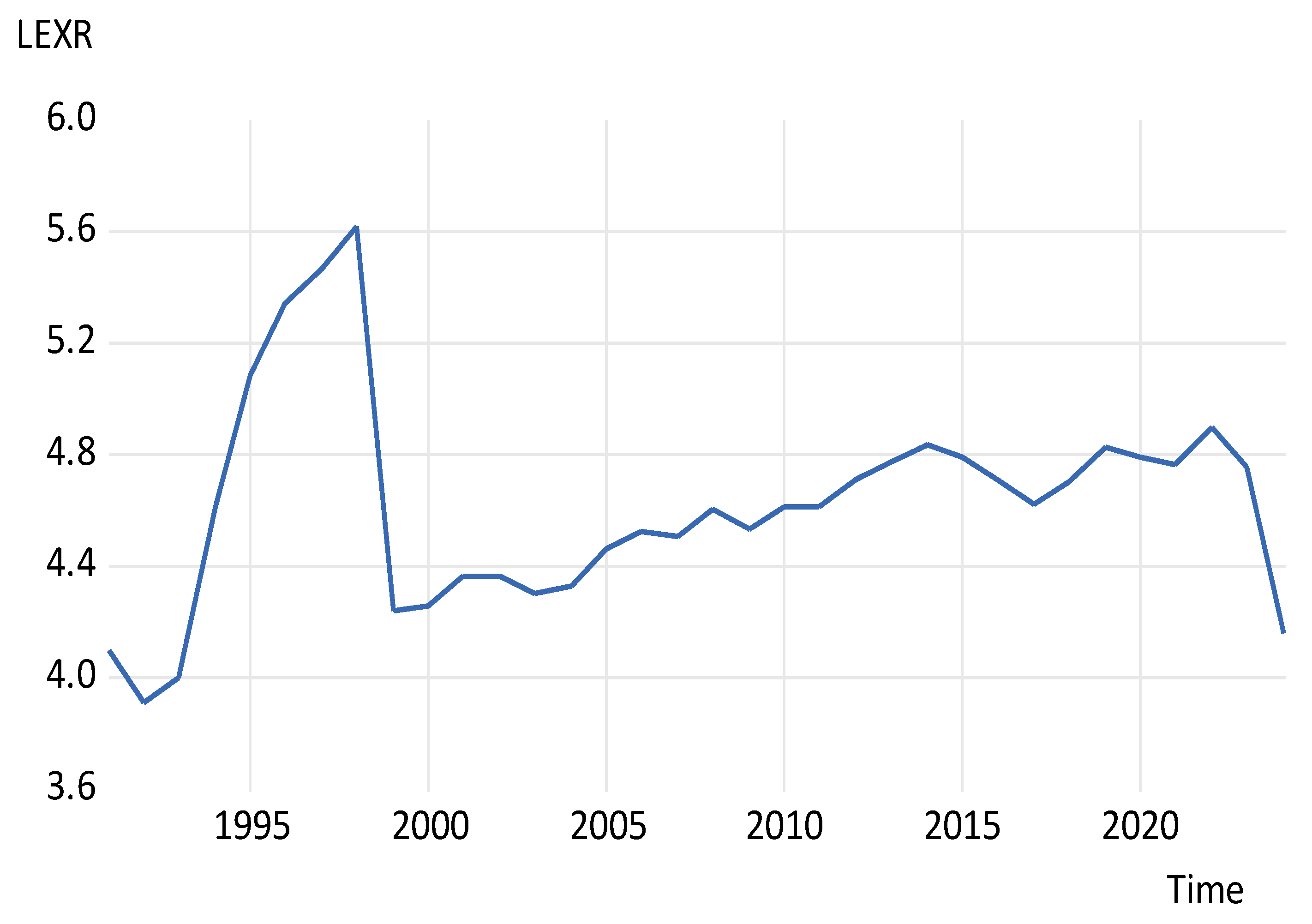

The trend of the exchange rate (LEXR) over time (

Figure 3) shows periods of both depreciation and appreciation of the Nigerian currency. In the early 1990s, the rate sharply declined to just under 4.0, reflecting significant appreciation. In the mid-to-late 1990s, the exchange rate climbed again, peaking around 5.5, showing another phase of depreciation, followed by a sudden drop to just above 4.0 in the late 1990s to early 2000s, after which it stabilized. From the 2000s to the mid-2010s, the exchange rate exhibited relative stability with a slight upward trend, fluctuating between 4.2 and 4.7, indicating slow depreciation. This gradual upward trend continued into the early 2020s, reaching around 4.8, before sharply declining to just above 4.0, signaling a sudden appreciation in the most recent period. Overall, the exchange rate experienced cycles of volatility with alternating periods of depreciation and appreciation over the years.

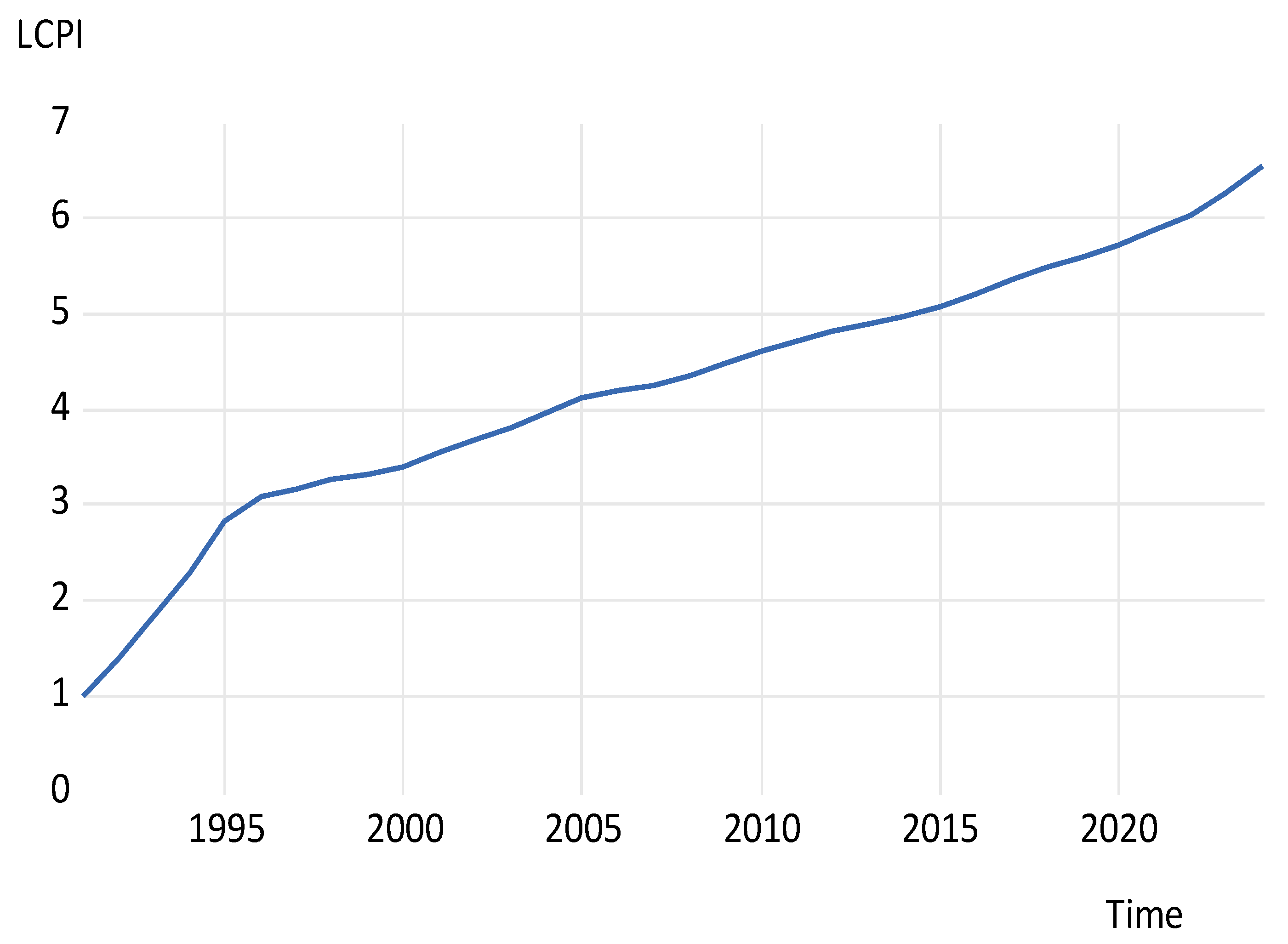

The trend of inflation (LCPI) (

Figure 4) shows a long-run and consistent upward trajectory from around 1991 to 2023, indicating a persistent inflationary environment in Nigeria. From the mid-1990s, inflation accelerated sharply, with LCPI rising from around 1 to nearly 3, suggesting rapid price increases during this period. Between the mid-1990s and early 2000s, the upward trend continued at a moderated pace, with LCPI increasing from about 3 to over 4. Throughout the 2000s to the 2010s, inflation remained steady, rising gradually from just above 4 to around 5. From the 2010s to the early 2020s, the upward trend intensified slightly, with LCPI surpassing 6, indicating continuing and possibly heightened inflationary pressures in recent years. Overall, the graph reflects a persistent rise in general price levels over the decades. This observed long-run upward trend in inflation is consistent with findings by [

45], which show that significant depreciation of the Nigerian Naira can shift inflation into a high regime, reflecting stronger persistence. Similarly, ref. [

46] document that CPI information shocks, exchange rate movements, and lending rate dynamics are significant drivers of volatility in food prices in Nigeria.

4.4. Unit Root Test Results (Augmented Dickey–Fuller and Phillips–Perron)

Table 3 reports the results of the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP) unit root tests conducted to ascertain the stochastic features of the variables used in the empirical model. The objective of the diagnostic test was to determine whether the series were stationary in levels or required differencing to achieve stationarity. The tests were implemented with an intercept and without a deterministic trend, based on basic macro-time series practice.

In both the ADF and PP frameworks, the null hypothesis of a unit root could not be rejected for all variables (PPV, LCPI, and LEXR) at their levels, as the correlated test statistics were insignificant at the 5 percent significance threshold. This outcome indicates that the level series are non-stationary and follow an integrated stochastic process. However, after the first differencing, the t-statistics for all variables became statistically significant under both ADF and PP tests, hence the rejection of the null hypothesis of non-stationarity. This confirms that each variable is stationary after first differencing.

The empirical evidence demonstrates that PPV, LCPI, and LEXR are integrated of order one, I(1). This general integration order has significant implications for the subsequent econometric strategy. Particularly, the presence of I(1) processes implies that shocks to any of the variables have persistent effects and do not dissolve in the short run. More importantly, since all variables share the same order of integration, the data-generating process satisfies the pre-requisite for examining potential long-run equilibrium relationships using cointegration techniques. Thus, this validates the application of the ARDL bounds testing approach on the model dynamics and lag structure.

4.5. ARDL Bounds Test for Cointegration

Table 4 presents the ARDL bounds test for cointegration among poultry price volatility (PPV), exchange rate (LEXR), and inflation (LCPI). The computed F-statistic of 4.4987 was higher than the upper critical bound (I(1)) at the 5% significance level, indicating the rejection of the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship.

4.6. ARDL Model Estimates for Poultry Price Volatility

The long-run coefficient which corresponds to PPV(-1) being the cointegration term was negative and significant (

p < 0.01), which supports the stable response of error correction where differences from equilibrium in the long run are corrected around 33.6% per period (

Table 5). This follows the basic ARDL cointegration theory model, which suggests that the adjustment period is very influential for the resumption of the system [

47]. The negative and significant long-run coefficient on LCPI indicates that inflation had a negative effect on PPV over time, thus the null hypothesis was rejected.

This is in accordance with other findings by [

48], which mention inflation’s restraining influence on purchasing power value in emerging markets. In contrast, the positive coefficient of LEXR indicated a beneficial long-run effect of the appreciation of the exchange rate on the PPV, consistent with the findings of [

49], which provides evidence for the impact of the exchange rate on trade competitiveness and purchasing power.

In the shorter term, positive and significant effects of the current variations in inflation (D(LCPI)) and lagged variations in PPV and exchange rate reinforce the difficult dynamic adjustments that occur before reaching equilibrium. Also, in this study, the large negative coefficient on lagged exchange rate changes D(LEXR(-1)) and D(LEXR(-2)) points to the short-run volatility effect, as reported by [

50], reinforcing temporal variability in the effects of exchange rates. The null hypothesis that inflation and exchange rate do not have a significant effect on poultry price volatility is therefore rejected. High adjusted R-squared (0.91) and strong F-statistics are a positive sign that the model fits well and does explain the findings.

A Wald test was conducted on the short-run differenced terms with the null hypothesis that all short-run coefficients are equal to zero. The result which is presented in the lower panel of

Table 6 confirms that the short-run dynamics are jointly significant, indicating that adjustments in CPI and exchange rate exert important short-run effects on poultry price volatility.

4.7. Diagnostic Tests for ARDL Model

A battery of diagnostics tests were performedafter estimating the ARDL model and are reported in

Table 6 and

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. The diagnostic tests indicate that the model was generally well-specified. The Breusch–Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test showed an F-statistic of 0.8170 (

p = 0.4594) and ObsR-squared of 2.7799 (

p = 0.2491), suggestingno evidence of serial correlation in the residuals. The Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey heteroskedasticity test showed mixed results: the F-statistic (2.7098,

p = 0.0294) suggests possible heteroskedasticity, but the Chi-square-based tests (

ObsR-squared

p = 0.0666 and scaled explained SS

p = 0.8963) mostly indicate that the residuals were approximately homoskedastic.

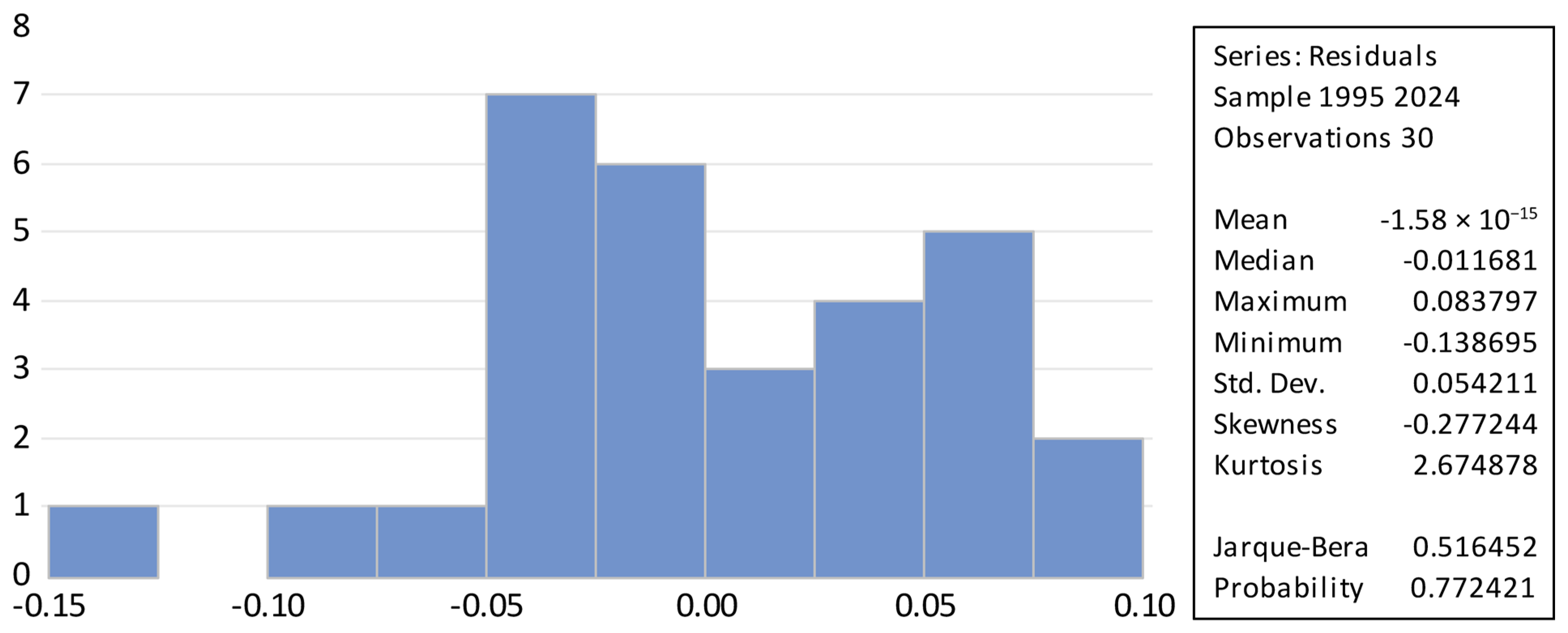

The histogram of the ARDL model residuals (

Figure 5) shows that the residuals are well-behaved and approximately normally distributed. The distribution is centered around zero, with a mean extremely close to zero (−1.58 × 10

−15), indicating no systematic bias in the model’s predictions. The residuals were roughly symmetrical, as reflected by a low skewness of −0.277, and the kurtosis of 2.675 suggests that the tails werenot excessively heavy. The Jarque–Bera test statistic of 0.516 with a

p-value of 0.772 further confirmed normality, as the null hypothesis of normally distributed residuals couldnot be rejected.

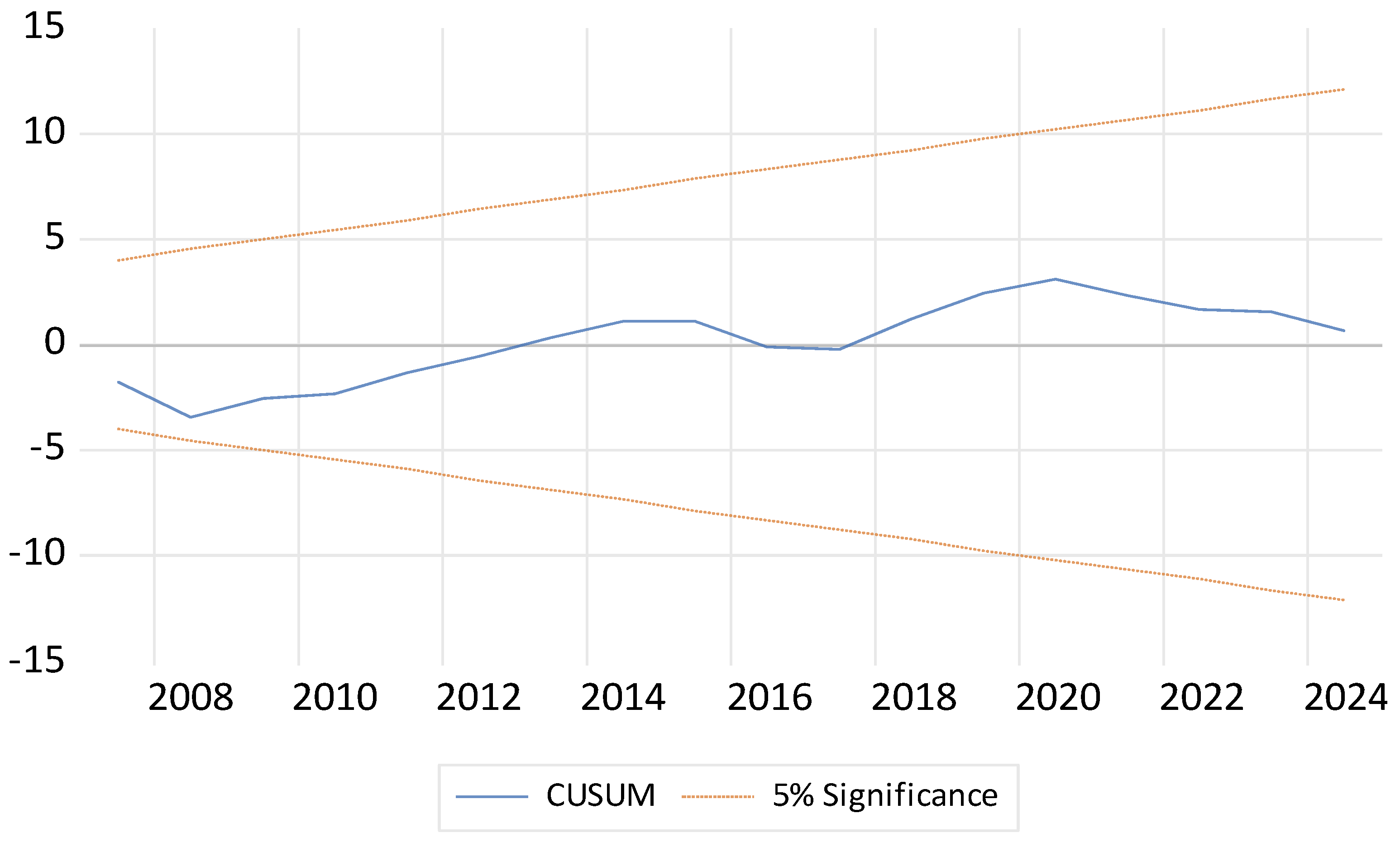

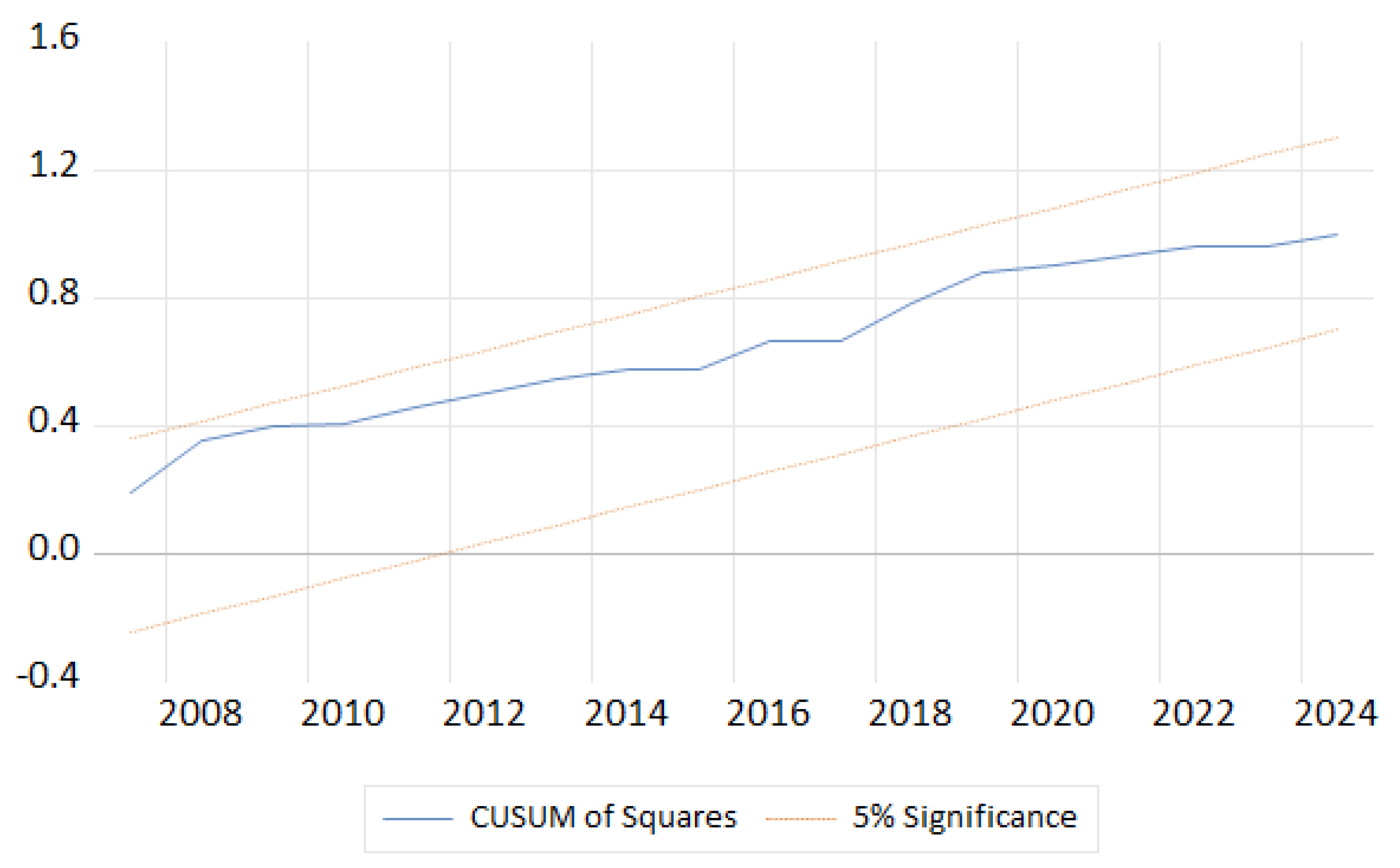

The CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots reveal that the cumulative sums of the recursive residuals stayed well within the critical limits during the sample period, indicating no structural breaks. This means the parameters in the ARDL model remained consistent over time. The CUSUM plot shows that the coefficients did not undergo sudden shifts, while the CUSUMSQ plot indicated that neither gradual variance nor gradual variation in variance could be anticipated. Taken together, these results confirm both the temporal consistency and the reliability of the estimated model. Accordingly, the model can be classified as robust for inference and forecasting.

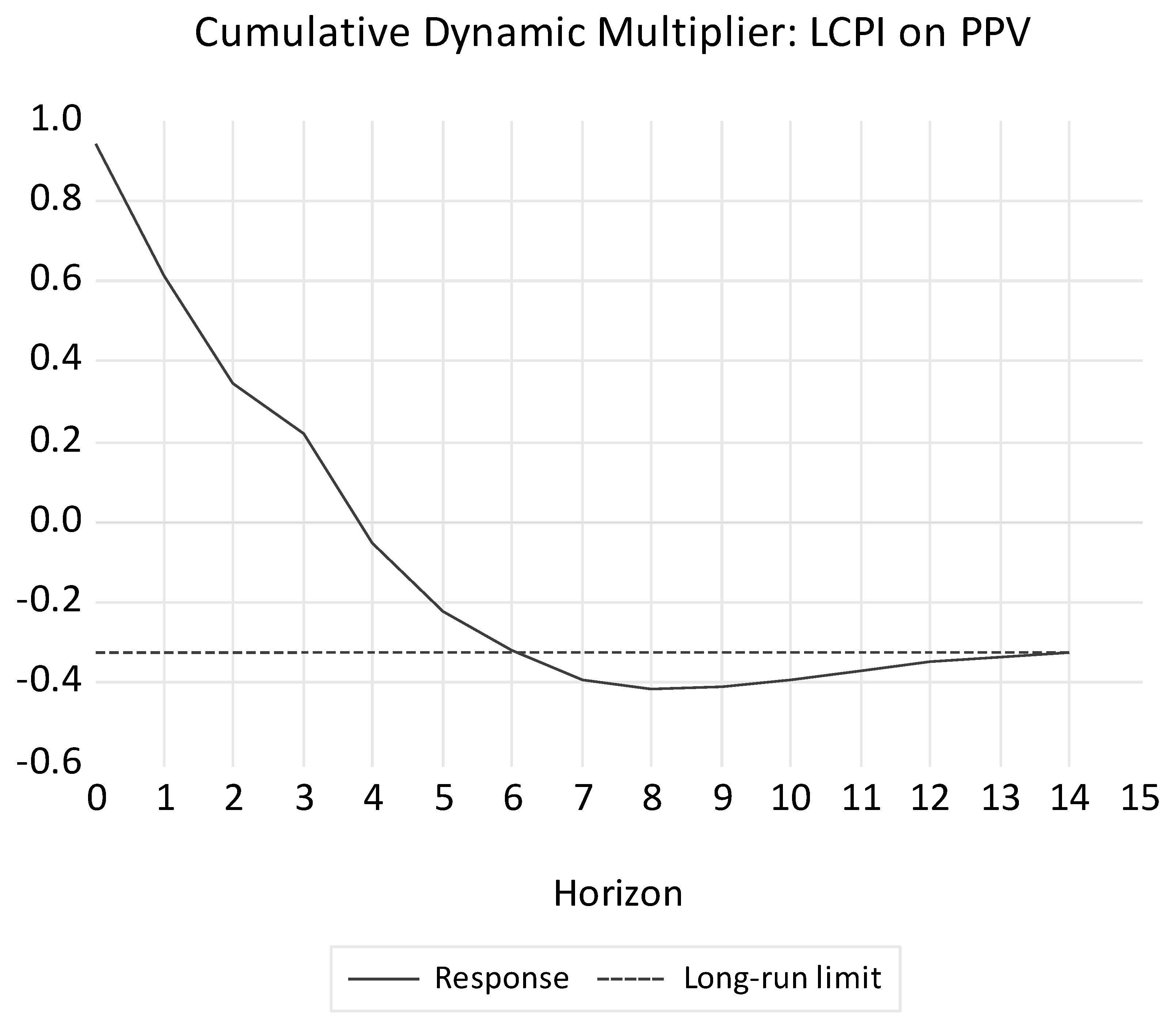

4.8. Cumulative Dynamic Multipliers

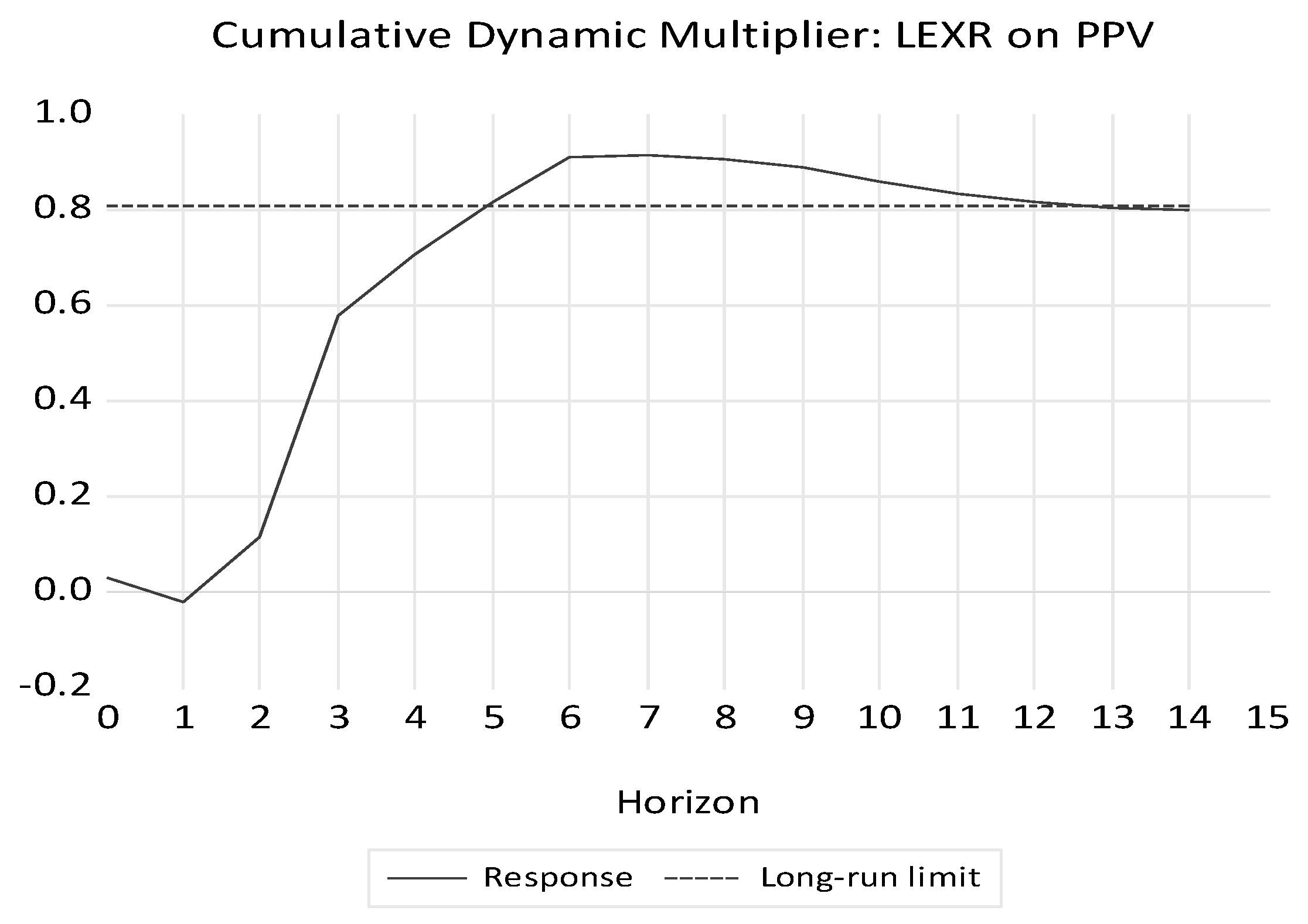

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the cumulative dynamic multiplier for the effect of exchange rate on product price volatility and the effect of inflation on product price volatility, respectively.

Figure 7 illustrates the long-run effect of a shock to the exchange rate (LEXR) on poultry price volatility (PPV). Initially, the response was negligible, with the effect remaining close to zero for the first two periods (horizon 0–2). However, from period 2 to 6, a positive and accelerating impact was observed, with the cumulative effect rising sharply to a peak around 0.9. This suggests that an exchange rate shock had a delayed but significant positive influence on poultry price volatility, meaning that, as the exchange rate changed, poultry prices became more volatile. Following the peak at period 6, the effect began to decline slightly, eventually stabilizing and converging to a long-run limit of approximately 0.8.

The cumulative dynamic multiplier (

Figure 8) shows the interaction dynamics between inflation, as expressed by the logarithm of consumer price index (LCPI), and poultry price volatility (PPV) in Nigeria. In the context of the short run (horizons 0–1) the response of PPV to an inflationary shock was highly positive and reached a maximum of around 1.0. This result indicates strong cost-push effects, as the higher prices of essentials, for instance, feed grains, energy, and transport, immediately leaked through into poultry prices, increasing volatility [

51,

52]. From horizon 4 onward, the response become negative; however, it stabilized around –0.35 in the long run, indicating that market-specific adaptation and structural adjustment will be occurring at the market level. Such a transition indicates that producers and traders slowly incorporated inflation expectations, adjusted inflation expectations, implemented a dynamic price structure, shifted from the use of imported inputs to local sources, and increased the efficiency of supply [

23,

53]. As a result, whereas inflation does rattle the market, long-run inflation may trigger structural response and learning behavior along the poultry value chain. At an economic level, this dynamic suggests that inflation pass-through can turn destabilizing into stabilizing effects over time. Accordingly, macroeconomic stability policy, domestic feed grain value chain strengthening, input efficiency, and exchange rate volatility management are essential for combating inflationary shocks, enhancing producer welfare and increasing access to affordable protein among Nigeria’s growing population [

5,

54].

4.9. Discussion

The descriptive statistics reveal that poultry price volatility (PPV) in Nigeria averaged 0.6546 over 1995–2024, but with a high standard deviation (1.0714) and strong positive skewness (1.7825), indicating occasional extreme spikes despite moderate average volatility. Exchange rate (LEXR) fluctuations were moderate (mean = 4.7943, Std. Dev. = 0.5914), showing periods of currency depreciation, while inflation (LCPI) was relatively stable (mean = 3.1524, left-skewed), implying more predictable price movements compared to poultry prices. The Jarque–Bera results confirm that PPV and LEXR deviated from normality, which may reflect the influence of external shocks, market imperfections, and policy changes, whereas LCPI follows a more regular distribution. These results are consistent with [

55], who also found agricultural commodity prices in Nigeria to be more volatile than macroeconomic indicators, and they reinforce the vulnerability of poultry markets to exchange rate and inflation shocks.

Poultry price volatility (PPV) analysis was clear and followed a definite path, from very high volatility in the early 1990s until it eventually reached its maximum value in 1995, then continued to decline to near-zero after 2005. This transformation was part of a structural change in Nigeria’s poultry system from a state of macroeconomic instability and external imbalances to an improved system of domestic coordination and production efficiency. The initial volatility was also due to exchange rate shocks, dependence on inputs from feed, and weak infrastructure that amplified the effects of global price transmission. In agricultural policy reforms including the Presidential Initiative on Livestock Development and the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy, the significant decrease due to the volatility of the sector of agriculture since the mid-2000s was observed. They enhanced local production capacity, promoted value chain integration, and reduced dependence on unpredictable imports. The development of vertically integrated poultry enterprises has facilitated feed supply, manufacturing and marketing, stabilizing market prices and creating supply consistency. These findings are consistent with [

56,

57], who noted that infrastructural and institutional improvements significantly decrease agricultural price volatility by improving coordination and market efficiency. It is, however, in contrast with [

58], who documented persistent volatility in other livestock sub-sectors, particularly beef and dairy, which resulted from climate variability and feed cost pressures. That difference highlights sectoral differences: shorter production cycles for poultry produce in less exposed settings, while ruminant production models are still susceptible to ecosystem impacts. Overall, the decrease in PPV post-2005 is a sign of the industrial maturation of Nigeria’s poultry market, backed by better value chain connections, domestic investments, and policies with strong consistency. The importance of long-run infrastructure and institutional development to ensure price stability and replicate comparable resilience in other livestock value chains is emphasized by the evidence.

The exchange rate trend demonstrates cycles of depreciation and appreciation, with notable instability in the 1990s, followed by relative stability in the 2000s and mild depreciation into the 2010s before a sharp recent appreciation. This cyclical movement reflects Nigeria’s history of policy regime changes, oil price shocks, and foreign exchange controls. The pattern supports findings by [

59], who documented that exchange rate volatility in Nigeria is heavily influenced by oil revenue fluctuations and government monetary policy adjustments. The relatively calmer 2000s suggest improved macroeconomic management compared to the structural adjustment era.

Nigeria’s inflation trend (LCPI) is consistent, and, since 1991, the inflation rate has shown a persistent upward trend, peaking most significantly around the mid-1990s under the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP), wherein policies such as currency devaluation, trade liberalization, and subsidy removal induced Cost-Push Inflation through higher import and production costs. Since the 2000s, inflation has been steady but increasing, underpinned by fiscal deficits, monetary expansion, and imported price pressures, implying that inflation has become a structural feature of Nigeria’s economy. As noted by [

60], this persistence in the long term is indicative of poor productivity, limited fiscal discipline, and market inefficiencies, and [

61] underline the weak role of conventional monetary policy, as it has minimal effect because of exchange rate misalignment and the limitations of supply chains. Likewise, ref. [

61] reports that external shocks and fluctuations in global commodity prices continue to drive higher imported inflation in sub-Saharan Africa. The close connection between food and headline inflation also indicates how agricultural bottlenecks and distributional inefficiencies affect consumer prices. In the aggregate, Nigeria’s inflation dynamics demonstrate a dynamic macroeconomic context in which partial stabilization endeavors are accompanied by entrenched structural limitations, demonstrating the requirement of continuous institutional reform and coordinated policies to achieve long-run price stability.

The unit root tests show that all variables were non-stationary at levels but became stationary after first differencing (PPV and LEXR clearly I(1), LCPI borderline I(1)), making the ARDL approach suitable. This implies that shocks to these variables had lasting effects, a typical feature of macroeconomic and commodity price series. Similar results have been reported by [

39], who found that Nigerian exchange rate and inflation series exhibit persistence, reflecting structural rigidities and delayed market adjustments.

The bounds test confirmed a long-run relationship among PPV, LEXR, and LCPI, with the F-statistic exceeding the upper bound at the 5% level. This indicates that, despite short-run fluctuations, these variables move together in the long run, suggesting that poultry price volatility is systematically linked to exchange rate and inflation dynamics. This supports the findings of [

60], that, in developing economies, food prices are closely tied to macroeconomic fundamentals, especially exchange rates.

The ARDL results indicated that poultry price volatility was highly persistent (PPV(-1) significant and positive) and influenced by both inflation and exchange rate dynamics. Inflation increases PPV contemporaneously but reduces it in the following period, suggesting a short-run cost push followed by market adjustment. Exchange rate effects are lagged and mixed, with some lags amplifying volatility and others dampening it, highlighting the complex transmission mechanism from currency fluctuations to poultry prices. The high R

2 suggests strong explanatory power, consistent with [

61], who also found exchange rate volatility to be a major driver of food price instability in Nigeria.

Diagnostic results indicated no serial correlation and generally acceptable homoskedasticity, although one heteroskedasticity measure suggested mild variance instability. This implies thatthe model wasstatistically reliable for inference. Similar robustness in ARDL estimations has been reported by [

37] when dealing with macroeconomic variables in small samples, supporting the credibility of these results.

The cumulative dynamic multiplier analysis revealed that exchange rate shocks had a delayed but significant positive impact on poultry price volatility, peaking around period six before stabilizing. This suggests that currency movements take time to pass through the poultry market, possibly due to contract lags, import dependency on feed inputs, and the gradual adjustment of consumer prices. The delayed transmission effect is consistent with [

55], who found that exchange rate shocks in Nigeria’s agricultural sector are not instantaneous but accumulate over several periods.

The residual distribution was approximately normal, with skewness and kurtosis close to ideal values and the Jarque–Bera test confirming normality. This supports the validity of the model’s statistical inferences. Comparable findings have been documented by [

40], who noted that normal residuals are common in well-specified ARDL models for macroeconomic series.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of poultry price volatility (PPV) dynamics in Nigeria in the context of exchange rate fluctuation (LEXR) and inflation (LCPI) from 1991 to 2024. Our bounds test confirms a stable long-run equilibrium relationship between these variables and further affirms the systematic relationship of poultry price to macroeconomic fundamentals. The fact that the volatility of the price of poultry is relatively long-lasting, and with it, the sensitivity of poultry against inflation or exchange rate shocks, make it a very sensitive sector amidst macroeconomic disruption. This evidence only adds weight to the contention that Nigerian poultry price instability is even worse than overall macroeconomic instability in Nigeria and results from imported feed dependence and exposure to external shocks.

The reduction in variation with reference to 2005 and our analysis corroborate the impact of structural reforms and policy measures (like the Presidential Initiative on Livestock Development and National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS)) that led to institutional integration, supply chain development, and increasing domestic production capacity. The high volatility of poultry price due to exchange rate shocks remains, but is mitigated at an initial, somewhat short-run stage, and it also represents short and embedded long-run cost-push mechanisms, as well as in response to macroeconomic signals in the poultry sector, the inflation phase. ARDL test and bounds test results suggest that macroeconomic–agricultural coordination coherence is required for long-run price stability in poultry.

Macroeconomic management and cohesive policy in various sectors will be essential in the stabilization of Nigeria’s poultry market according to the study. Through the implementation of more effective exchange rate management, the lagged and magnified influence of currency volatility on poultry price instability can be mitigated. A corresponding response is necessary if we want to reduce the short-run shocks and the volatility in prices of producer income, to manage inflation through the realistic harmonization of monetary and fiscal policy.

Policy priorities should be directed to the following: expanding and strengthening the domestic feed grain value chain to reduce foreign exchange liabilities and enhance cost competitiveness; diversifying local feed ingredient production, veterinary service and cold chain infrastructure investment; increasing market information systems and data-driven monitoring for the early warning of volatility shocks; advancing price stabilization and rural logistics tooling to reduce transaction costs and improve market integration; encouragingsmall- to medium-size animal husbandry businessesto finance, use risk management tools, and make institutional linkages, and promoting technical innovation and PPP and technology transformation to upgrade the poultry production and distribution system. On aggregate, these measures could bolster the poultry sector’s resilience while allowing inclusive, innovation-based growth.

Further study is needed to investigate asymmetrical and non-linear impacts of exchange rate and inflation shocks on the poultry product sector and production scales. The integration of climate swings, feed price cycles, and digital market intelligence systems into volatility models would offer a clearer policy context and yield greater predictive power. Comparative studies on West African countries could complement the Nigerian experience and help to identify the regional food market stabilization regimes.

Nigeria’s poultry industry has attained a relatively stable and advanced stage, largely attributable to macroeconomic policy reforms, increased domestic investment, and institutional strengthening. However, sustaining this progress will require a gradual macroeconomic stabilization, the upgrading of infrastructure, and innovation in productivity growth. Lastly, a comprehensive and coordinated policy framework, which integrates macroeconomic stability, sectoral productivity, and supply chain efficiency, is required to stabilize poultry prices and provide for producers’ livelihoods, and to increase access to protein for the expanding population to access affordable protein.