1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are critical for a variety of modern technologies including electric vehicles (EVs), drones, battery energy storage (BESS), consumer electronics (e.g., laptops and smart phones), and more [

1]. These technologies improve energy efficiency in transportation, mitigate the impacts of intermittency in emission-free energy production technologies, and improve economic productivity [

2]. As a result the demand for LIBs continues to grow, which means the supply chain that provides the materials for LIBs must grow as well. LIBs consist of a cathode comprising lithium-metal oxides (the most popular being nickel–manganese–cobalt [NMC] and iron phosphate [LFP]), an anode (generally made from graphite but with silicon additions becoming increasingly popular), and an electrolyte (typically lithium hexafluorophosphate). Each of these components have their own extensive supply chains with unique and shared challenges including geopolitical risk and production concentration that LIB producers and consumers increasingly need to be cognizant of [

3]. This is especially true for the supply chains of critical minerals.

This study focuses on six metals central to mainstream LIBs—nickel, manganese, cobalt, lithium, aluminum, and copper. We focus on the metals in NMC batteries because they are currently the most popular; the other most popular battery chemistry LFP consists of relatively common metals with diverse production and processing supply chains, and as a result the six metals we focus on are labeled as critical minerals. This study maps the upstream supply of six metals critical to lithium-ion batteries using USGS data, company reports, and Bloomberg Terminal outputs to create a harmonized dataset across supply-chain stages. Supply security is shaped not only by resource availability but also by corporate concentration and geopolitical positioning. The study provides a transparent 2024 baseline to track future supply shifts and strategies to secure the energy and critical minerals supply chains for the technologies of the future.

A core motivation for our work is that geographic diversity upstream (mining) often gives way to greater concentration midstream (refining/precursors), creating exposure to policy, logistics, and energy-price shocks in a small number of processing hubs [

4]. Recent international assessments show refining and processing of critical minerals—including copper, nickel, cobalt, lithium, and manganese—are disproportionately located in East Asia, reinforcing systemic bottlenecks even as global demand grows [

4].

Building on this context, we assemble a two-layer empirical framework for calendar year 2024: (i) country totals from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) as the reference for global production by nation [

5], and (ii) company-level production and flows compiled from finance-screening outputs and verified against company disclosures, then reconciled to the country layer via explicit attribution rules (JV-share splits, operator vs. owner, and year alignment).

Scope and Boundaries

The quantitative scope and boundaries of this analysis include coverage of Li, Ni, Co, Mn, and Cu mine production (measured in metric tons) as well as primary aluminum output at the smelter gate. The qualitative scope includes major processing destinations identified in the research but this study excludes quantitative exploration of downstream activities. Therefore, the out-of-scope includes totals for downstream products such as LiOH/LCE, Ni/Co/Mn sulfate or matte flows, and Al/Cu foils, which are referenced only narratively. Company-totals and company-in-country totals are compiled for each metal, using the most recent and consistently reported year for each. World totals are fixed per metal and year to ensure consistent share calculations.

2. Background

2.1. Case Background: Functions of Key Metals in NMC-Based LIBs

The cathode chemistry of nickel–manganese–cobalt (NMC) lithium-ion batteries relies on a layered oxide in which Ni, Mn, and Co jointly determine the specific capacity and structural stability of the cathode, while Li serves as the charge carrier and Al/Cu act as lightweight, conductive current collectors that enable efficient electron transport at the cathode and anode, respectively. Within NMC cathodes, higher Ni content raises specific capacity but increases structural- and thermal-management challenges, whereas Co improves electronic and structural stability and Mn enhances lattice and thermal stability at a lower cost, motivating a system-wide view of supply for all six metals [

6].

2.1.1. Nickel (Ni)

Nickel is the principal capacity contributor in NMC cathodes: increasing Ni content introduces more redox-active

/

couples which yield higher specific capacity [

7,

8]. However, Ni-rich cathodes suffer from structural instabilities, such as surface reconstruction, oxygen release, cation mixing, and lattice distortion, which accelerate degradation [

8]. To mitigate these drawbacks, strategies such as targeted doping, robust surface coatings, compositional gradients, and optimized microstructure or particle design are commonly employed [

7,

9].

2.1.2. Manganese (Mn)

Manganese improves the structural and thermal stability of layered NMC and helps lower cost relative to cobalt-heavy chemistries [

10]. It can participate in reversible redox reactions alongside Ni and Co and contributes to voltage-profile shaping, although in practice its primary role is stabilization rather than direct capacity contribution [

10].

2.1.3. Cobalt (Co)

Cobalt stabilizes the layered structure, enhances electronic conductivity, and improves rate capability and cycle life, especially at moderate Ni contents [

10]. Reducing Co content (toward Ni-rich NMC) maintains high energy density but requires countermeasures such as surface coatings and compositionally graded particles to preserve safety and longevity [

10,

11].

2.1.4. Lithium (Li)

Lithium is the charge carrier that shuttles between electrodes; in NMC cells it intercalates and de-intercalates in the layered oxide cathode and in the anode during charge and discharge [

12]. NMC electrochemistry is governed by Li-vacancy creation and transition-metal redox, which together determine capacity, operating voltage, and dominant fade pathways [

12].

2.1.5. Aluminium (Al)

Aluminium serves as the standard

cathode current collector because it resists oxidation at high potentials (≈3.7–4.3 V vs. Li/

) where copper would corrode [

13]. Al foils—and emerging three-dimensional Al foams—provide low mass, high conductivity, and corrosion resistance, enabling high-areal-capacity NMC electrodes [

14]. Using copper on the cathode is avoided because Cu oxidizes above about 3.5 V, degrading performance; thus, Al is mandatory on the cathode side [

15].

2.1.6. Copper (Cu)

Copper is the standard

anode current collector because it remains stable at low potentials (near 0 V vs. Li/

), offers high conductivity, and adheres well to anode coatings [

16]. Interface engineering of Cu—such as texturing, protective coatings, or three-dimensional structures—improves adhesion and rate capability and reduces impedance growth, which is important for high-power electric vehicle duty cycles [

17]. At end of life, both Cu and Al foils can be directly reused after cleaning, supporting circularity and reducing pack cost and

emissions [

18,

19].

2.2. How These Metals Shape EV Outcomes (with NMC)

Energy density and range: NMC’s higher cell-level energy density than LFP (owing largely to Ni-enabled capacity) helps extend EV driving range and reduce pack mass [

20].

Pack-level reality: Gains at cell level partially dilute at pack level (thermal management, safety margins), but NMC/NCA still lead volumetric/gravimetric density for long-range EVs [

21].

Cost/stability trade-offs: Mn helps stabilize and lower cost; Co enhances stability/conductivity but adds cost/ethical-sourcing pressure; high-Ni designs require coatings/doping and tight control of particle micro-cracking to preserve cycle life under EV fast-charge/high-power use [

10,

11].

Sustainability and regional context: NMC production and precursor supply today are geographically concentrated; LCA outcomes depend strongly on energy mix and recycling inputs; several studies show NMC can be environmentally favorable when recycling is included [

22].

2.3. Mining and Processing of Key Metals

2.3.1. Aluminum—Mining (Bauxite Extraction → Crushing/Screening → Refining to Alumina)

Primary aluminum production originates from bauxite, a lateritic ore containing gibbsite, boehmite, and diaspore. Most deposits are shallow and laterally extensive, favoring open-pit mining with truck–shovel fleets and surface miners for bulk extraction [

23]. Run-of-mine bauxite is typically crushed and screened before stockpiling, with blending practices used to control alumina, silica, and moisture contents critical for downstream processing [

24]. In high-grade ores beneficiation is limited, but clay-rich or reactive-silica-bearing bauxites require washing, desliming, and size classification to reduce impurities and caustic consumption in Bayer digestion [

25]. Once beneficiated, the ore is refined to alumina by the Bayer process, where sodium hydroxide selectively dissolves aluminum oxides under high temperature and pressure, leaving behind iron-rich “red mud” residues. Refining efficiency depends on particle size, feed mineralogy, and process control [

26]. Global supply is dominated by a few large-scale surface mines in Australia, Guinea, Brazil, and China, underscoring the geographic concentration of primary aluminum resources [

23,

27].

2.3.2. Nickel—Mining (Sulfide Ores → Crushing/Milling/Flotation; Laterites → Drying/Reduction/Leaching)

Nickel resources occur mainly as sulfide and laterite ores, with extraction routes determined by deposit type. Sulfide ores such as those at Norilsk and Sudbury are commonly mined underground, while disseminated bodies permit open-pit operations. After extraction, ore is crushed and milled before undergoing froth flotation to concentrate Ni–Cu sulfides, with selective flotation and magnetic separation enhancing recovery of pentlandite and pyrrhotite [

28]. Concentrates are smelted to matte and refined hydrometallurgically, often through pressure oxidation (POX) or chloride leaching [

29]. Laterite deposits, which constitute the bulk of global nickel resources (notably in Indonesia and the Philippines), are mined via large-scale open-pits. Beneficiation is limited but includes drying, screening, and ore blending to manage Mg:Fe ratios and moisture before processing. Limonitic laterites are treated with High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) to produce mixed hydroxide/sulfide precipitates, whereas saprolitic ores are processed by the Rotary Kiln–Electric Furnace (RKEF) route to make ferronickel [

30,

31]. Studies highlight that ore blending, stockpile management, and particle-size optimization are crucial to stabilizing feed and maximizing recovery, linking mine-to-plant design directly to battery-grade precursor production [

32,

33]. Global supply is now dominated by laterite projects in Southeast Asia, reshaping trade flows and increasing dependence on energy- and acid-intensive hydrometallurgical routes [

29].

2.3.3. Lithium—Mining (Hard-Rock Spodumene → Crushing/Flotation; Brines → Evaporation/Precipitation)

Lithium resources are hosted mainly in hard-rock pegmatites and continental brines, with mining approaches shaped by deposit type. Hard-rock spodumene deposits, notably in Western Australia (e.g., Greenbushes, Pilgangoora), are mined via large-scale open-pit methods. The ore undergoes multi-stage crushing, milling, and froth flotation to produce spodumene concentrates, typically graded as SC6 (6%

O) [

34,

35]. Concentrates are calcined at high temperature to transform

-spodumene into the more reactive

-phase, before sulfuric acid roasting and water leaching yield lithium sulfate, which is converted into lithium carbonate or hydroxide for battery applications [

36]. Continental brine resources, dominant in Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, are produced by pumping Li-rich brines to surface evaporation ponds. Sequential salt precipitation (Na, K, Mg, Ca removal) concentrates the brine to high LiCl grades, which are then processed to lithium carbonate or hydroxide [

37]. Brine projects face challenges such as water balance, Mg:Li ratio management, and long residence times, while Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) technologies are under development to improve recovery and reduce environmental impacts [

38]. Globally, supply is increasingly concentrated in Australia (hard-rock) and South America (brines), with emerging projects in Africa and China diversifying feedstock availability [

35].

2.3.4. Cobalt—Mining (Sulfide Ores → Flotation/Smelting; Laterites → HPAL/Pyrometallurgy)

Cobalt occurs primarily as a by-product of copper and nickel extraction, with distinct processing pathways depending on deposit type. In magmatic sulfide systems (e.g., Sudbury in Canada, Norilsk in Russia), cobalt is recovered alongside nickel and copper. Ores are crushed and milled, followed by froth flotation to concentrate Ni–Cu–Co sulfides. These concentrates are smelted to matte, then refined hydrometallurgically through pressure oxidation or solvent extraction circuits [

39,

40]. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which supplies more than 70% of global mined cobalt, stratiform Cu–Co oxide ores dominate. These are extracted by open-pit mining, then processed via crushing, milling, and sulfuric acid leaching. Leach solutions are refined using solvent extraction and electrowinning (SX–EW) to yield cobalt metal or intermediates [

41,

42]. Increasingly, laterite-hosted cobalt resources in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea are exploited through High-Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL) to produce mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP) or mixed sulfide precipitate (MSP) for the battery supply chain [

30,

43]. Key industry challenges include impurity management (Fe, Mn, Cu), high acid and energy requirements, and sustainability concerns linked to artisanal mining, child labor, and geopolitical risks in the DRC [

44,

45]. The shift toward laterite-based HPAL projects is reshaping global trade flows, with Asian refineries emerging as central hubs in the cobalt supply chain [

40,

43].

2.3.5. Manganese—Mining (Extraction → Crushing/Screening → Beneficiation)

Most manganese is mined from sedimentary oxide deposits such as pyrolusite, with large-scale open-pit mining being the dominant method, though underground approaches exist for steeper or deeper ore bodies [

46]. Once extracted, run-of-mine ore is crushed and screened into size classes for further upgrading to meet metallurgical and battery specifications [

46]. For coarser ores where manganese oxides are well liberated, gravity separation techniques such as jigs and shaking tables are widely employed. These processes take advantage of the high density of Mn oxides to raise the grade at relatively modest energy cost, with pilot and plant studies showing that jigging can effectively upgrade low-grade fractions (1–10 mm) when liberation is sufficient [

47]. When manganese is finely intergrown with iron or silica, beneficiation circuits incorporate magnetic separation—either dry or wet—after crushing and screening to enhance the Mn:Fe ratio before any hydrometallurgical steps [

48]. Fine or clay-rich ores often require scrubbing and desliming prior to gravity or magnetic separation to prevent slime entrainment and to stabilize jig performance. Route selection is dictated by mineralogy and particle size: coarse liberated oxides favor gravity methods, while Fe-rich or finer textures require magnetic or combined flowsheets to achieve high-grade concentrates at minimal energy or reagent cost. In battery-focused projects, mine-to-plant interfaces such as blast fragmentation, crusher settings, and stockpile blending are optimized to ensure consistent leach feed downstream [

49]. Global supply data emphasize that these beneficiation steps are critical to meeting market specifications, with the majority of output controlled by a few large-scale surface mines [

46].

2.3.6. Copper—Mining (Sulfide vs. Oxide Routes; Pit → Concentration/Leach)

Copper production is dominated by large open-pit porphyry deposits, typically containing less than 1% Cu, mined through drill–blast and truck–shovel operations. After extraction, ore is crushed and ground to liberate valuable minerals, with the subsequent treatment determined by mineralogy: flotation for sulfides or acid leaching for oxides [

50]. Sulfide ores such as chalcopyrite and bornite are upgraded via froth flotation, producing Cu-rich concentrates that are sent to smelters, with reagent suites (collectors, frothers, depressants) tailored to the ore characteristics. Mine planners must balance blast fragmentation and milling throughput to achieve target recovery at the design grind size while managing energy costs [

51]. Mixed ore bodies are often handled by stockpiling oxide-rich zones for hydrometallurgical processing while routing sulfides to concentrators, maximizing utilization of all ore types [

50].

Oxide ores are generally treated by heap or dump leaching using dilute sulfuric acid, with engineered pads incorporating liners and collection systems to optimize percolation and control recovery [

52]. The resulting leach solutions are processed by solvent extraction (SX) and electrowinning (EW), producing 99.99% cathode copper at mine sites [

52]. Many mining districts operate dual flowsheets, running both sulfide concentrators and oxide leach pads in parallel, with mine scheduling adapted to variations in ore hardness, grade, and weather, all of which influence throughput, acid consumption, and recovery rates. According to USGS summaries, flowsheet selection and performance vary widely depending on country and deposit style, reflecting the need for flexible and integrated approaches in global copper production [

53].

2.4. Material Flow Analysis Literature

Recent work has begun to explicitly quantify the

where and

when of LIB material flows. Busch et al. develop a dynamic, scenario-based framework that maps how future lithium extraction shifts geographically under different demand and recycling assumptions, showing that higher end-of-life recovery can defer greenfield mining and reallocate extraction across regions over time [

54]. These pathways are also explored in [

55], which investigate low-cost approaches for producing black mass and managing the reverse supply chain for lithium. In parallel, Wesselkämper et al. compare direct recycling with second-use pathways, estimating the timing and magnitude of secondary material supply from retired EV packs and its potential to displace primary extraction and reduce climate impacts [

56].

Complementary MFAs add spatial granularity and stock–flow timing. A national-scale study for the Republic of Korea enumerates 33 unit processes and 170 inter-stage flows across manufacturing, in-use, collection, and treatment, revealing where materials accumulate and leak within a country system [

57]. Dynamic MFAs spanning Li, Co, Ni, and Mn link demand scenarios and lifetime distributions to time-stamped requirements and end-of-life streams, providing inputs for capacity planning in mining, refining, and recycling [

58,

59]. Finally, market-wide assessments by the IEA synthesize today’s geographic concentration in refining and precursor production, offering a macro “where” backdrop that complements bottom-up MFAs and highlights midstream chokepoints relevant to near-term risk [

4]. Recent cross-market analyses such as Dimitriadis et al. [

60] were also informative, demonstrating how integrating traditional and digital data sources can illuminate dynamic linkages between resource markets and broader economic systems—an approach that motivates our effort to reconcile multi-source production data. Other work investigates the reverse supply chain of critical minerals, which entails recovering these minerals from end uses typically lithium ion batteries, completing the loop from production to recycling [

55,

61].

While this body of work advances understanding of dynamic flows and scenario modeling, relatively few studies address the methodological foundations for compiling and validating multi-source mineral production data. Methodological contributions by Graedel et al. [

62], Hatayama and Daigo [

63], and Pauliuk and Heeren [

64] outline procedures for reconciling heterogeneous statistics, propagating uncertainty, and ensuring internal consistency in material flow databases. Building on these approaches, our study harmonizes company-level disclosures with national production datasets to develop a consistent, country- and company-resolved map of upstream extraction. This framework strengthens data comparability across commodities and improves the empirical basis for analyzing geographic concentration in extraction activities.

Our study therefore contributes a cross-commodity, company- and country-resolved snapshot anchored to the latest production year, reconciling corporate disclosures with national totals. Whereas prior work often models future flows or single-country systems, we quantify where upstream production sits now and link it to known midstream hubs from external reviews, clarifying near-term exposure points in LIB supply chains.

2.5. Literature Gap

Existing analyses of lithium-ion battery (LIB) supply chains tend to focus either on forward-looking scenarios or on single-metal, single-country systems, which makes it hard to compare exposure across commodities and to ground policy in what is happening now. A further gap is the lack of a transparent, reproducible reconciliation between company disclosures and country totals, especially where joint ventures, operator–owner splits, and reporting lags create inconsistencies. Finally, while midstream concentration is often discussed qualitatively, most studies stop short of providing a synchronized, company–country baseline that quantifies how upstream production is distributed across firms and geographies in the most recent year.

This paper addresses those gaps by building a cross-commodity, cross-company map of the upstream for six LIB-relevant metals anchored to a single production year. We introduce explicit attribution and scaling rules (including JV-share handling and country re-balancing) to reconcile corporate totals with national aggregates, and we publish harmonized tables at both the company-total and company-in-country levels. The result is a decision-ready snapshot of where upstream production sits today, normalized across metals so that risks, dependencies, and diversification options can be compared on a like-for-like basis.

Beyond establishing a clean baseline, our approach links that upstream map to known midstream hubs, turning abstract “concentration” into measurable exposure for each metal and corporate actor. By standardizing the units, aggregation logic, and share calculations, the work enables benchmarking across time (future updates) and across studies (replication by others), filling the practical need for a transparent, method-driven foundation on which scenario modeling, resilience planning, and policy design can confidently build.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Scope

We conduct a cross-sectional, asset-to-corporation mapping of six Li-ion battery metals—copper, aluminum, lithium, cobalt, manganese, and nickel—covering mining and refining/consumer flow signals for the calendar year 2024. Units of analysis are (i) company-level production, (ii) company-by-country production allocations, and (iii) country totals.

3.2. Data Sources and Screening

Bloomberg Equity Screening. Using the Bloomberg Terminal Equity Screening tool, we filtered Sector = Materials and set Revenue ≥ USD 1000 M and Market Cap ≥ USD 1000 M. From the results, we added a custom column for the metal of interest (e.g., “Mined Copper (tonnes)”). Where Bloomberg provided mine/refinery and consumer locations, we recorded them for flow mapping.

Company reports. For each metal, we examined the top firms returned by screening and verified mined tonnage in the most recent annual/technical reports (e.g., Form 10-K, annual report, NI 43-101/JORC). When values differed from Bloomberg, we adopted the company’s report as the authoritative source.

USGS country totals (2024). We collected country-level production totals from the U.S. Geological Survey Mineral Commodity Summaries (MCS) and commodity-specific reports.

Supply-chain flows in Bloomberg. Where available, we used Bloomberg’s supply-chain/sales analytics to identify consumer geographies for each producing company.

3.3. Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI)

We quantify production concentration using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), which sums the squares of each producer’s percentage market share:

where

is the percentage market share of producer

i and

N is the total number of producers. HHI values range from near 0 (highly fragmented) to 10,000 (single-producer monopoly). An HHI value of 10,000 represents a pure monopoly, while scores above 2500 indicate a highly concentrated industry. Values between 1500 and 2500 reflect moderate concentration, those below 1500 signify an unconcentrated market, and figures under 100 denote a highly competitive environment. We calculated HHI for both country-level and company-level production for each mineral, focusing on the top three producers to capture the largest contributors to global supply [

65].

3.4. Core Tables Built

- 1.

Company–country allocation table: Production Country, Corporation, HQ, Company Production in Country, Country Production, % of Country Production, Sources.

- 2.

Company-totals table: Corporation, HQ, Total Company Production, Total Worldwide Produced [metal], % of Global Market.

- 3.

Mapping table for flow visualization: Ticker, Name, HQ Country, Mining—[Metal] Mined Production, Mining Locations 1–4, Consumer Locations 1–4.

3.5. Harmonization, Attribution, and QA Rules

Company identity and HQ. We normalized issuer names (parent vs. subsidiaries) and assigned ultimate parent HQ from Bloomberg.

Attribution. Production volumes are attributed to the ultimate parent corporation; for company-by-country allocations we apply the frequency-based rule below.

Conflicts and overrides. If the sum of a company’s site-level outputs exceeded the corresponding USGS country total, we retained the company totals and adjusted the country value upward, documenting the override.

Units. All production is recorded as metal contained (Mt or kt) for 2024.

De-duplication. Duplicate assets across sources were merged; for cross-border sites, operator-reported splits were used where available.

3.6. Country Allocation from Company Evidence

In this study, we implemented a frequency-weighted country-allocation approach to ensure realistic distribution of company production across mining jurisdictions. This method assumes that a higher frequency of a country appearing in Bloomberg datasets and company disclosures reflect greater mining intensity and thus a larger share of actual production. Assigning equal weights would imply uniform production across all listed countries, which would overlook substantial variation in ore grades, mine capacities, and corporate asset portfolios. The frequency-based rule therefore provides a more evidence-aligned and transparent assumption for reconciling company-by-country allocations.

For each company c and metal m, Bloomberg provides up to four mining source countries. We estimate company-by-country splits using a frequency-weighted allocation, then scale to match USGS totals.

- Step 1:

Frequency Weights.

For a company

c, let

be the count of mentions of country

k across listed sources. Let

be the total frequency. The initial allocation weight is

- Step 2:

Company Total Split.

Let

be the verified total mined tonnage for company

c. The initial allocation to country

k is

- Step 3:

Country Scaling to USGS.

For country

k, compute the pre-scale sum

Let

be the USGS total for country

k. Define the scale factor

The scaled company production in country

k is

Exception rule: if based on verified values exceeds materially, we set and raise to the company-verified total, documenting the change.

3.7. Derived Metrics

% of Country Production (by company): % of Global Market (by company): Additionally, to reconcile inconsistencies between company totals and USGS country aggregates, company-reported production figures were adopted as the authoritative reference whenever discrepancies were identified. Company reports and technical filings generally capture direct, site-level operational data that are timelier than aggregated USGS estimates. When verified company totals exceeded the corresponding USGS figures, the country total was adjusted upward to maintain internal consistency, and each override was recorded in a reconciliation log. This procedure may introduce a slight upward bias if overlapping assets or reporting-period differences occur; however, these cases were limited and did not materially influence concentration outcomes. Future updates will incorporate cross-validation with newer USGS releases and third-party databases to further reduce such residual differences.

3.8. Reconciliation of Company Totals and National Aggregates

A reconciliation procedure was implemented to ensure consistency between company-reported production totals and USGS country aggregates. Minor discrepancies were identified only for manganese and copper, where company totals slightly exceeded USGS values. In these cases, country totals were adjusted upward to match verified company data, with changes marked by asterisks for transparency. For all other metals, including aluminum, nickel, lithium, and cobalt, company and USGS figures were consistent. Because the adjustments were limited and small in magnitude, their effect on concentration metrics and company rankings was negligible. When differences occurred, company data were treated as the authoritative source since they provide more current, site-level information, while USGS estimates are compiled annually and may lag. All overrides were recorded in a reconciliation log, and although this approach could introduce a slight upward bias in rare cases, it ensured internal consistency and a more accurate reflection of actual production activity.

3.9. Supply-Chain Mapping

From Bloomberg’s supply-chain view, we recorded consumer locations for each issuer and joined them to the mapping table. These were used to build (i) country-to-country flow maps and (ii) company-to-country Sankey diagrams.

3.10. Software and Reproducibility

Data collection and cleaning were performed in Excel/Google Sheets; aggregation and scaling in Python 3.11 (pandas) or Excel; maps and Sankeys in Power BI 2/Python (Plotly). We archived (i) Bloomberg screening filters, (ii) company-report links, (iii) USGS tables, and (iv) scaling spreadsheets to ensure reproducibility.

3.11. Limitations

Limitations of our study include incomplete disclosure of site-level outputs by diversified miners, lags in USGS 2024 reporting, and the heuristic nature of frequency-based allocations where mine-level tonnages are not published.

4. Results

For each of the six explored metals we present the mine production by largest producing countries and companies. We highlight where these companies are headquartered, how much market share they have, and where they send their material to be processed. Then, we calculate how concentrated each metals are using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index.

We visualize these results using global maps to illustrate what mineral is produced (circles that are bigger for higher production), where it is produced, and by whom (country and company).

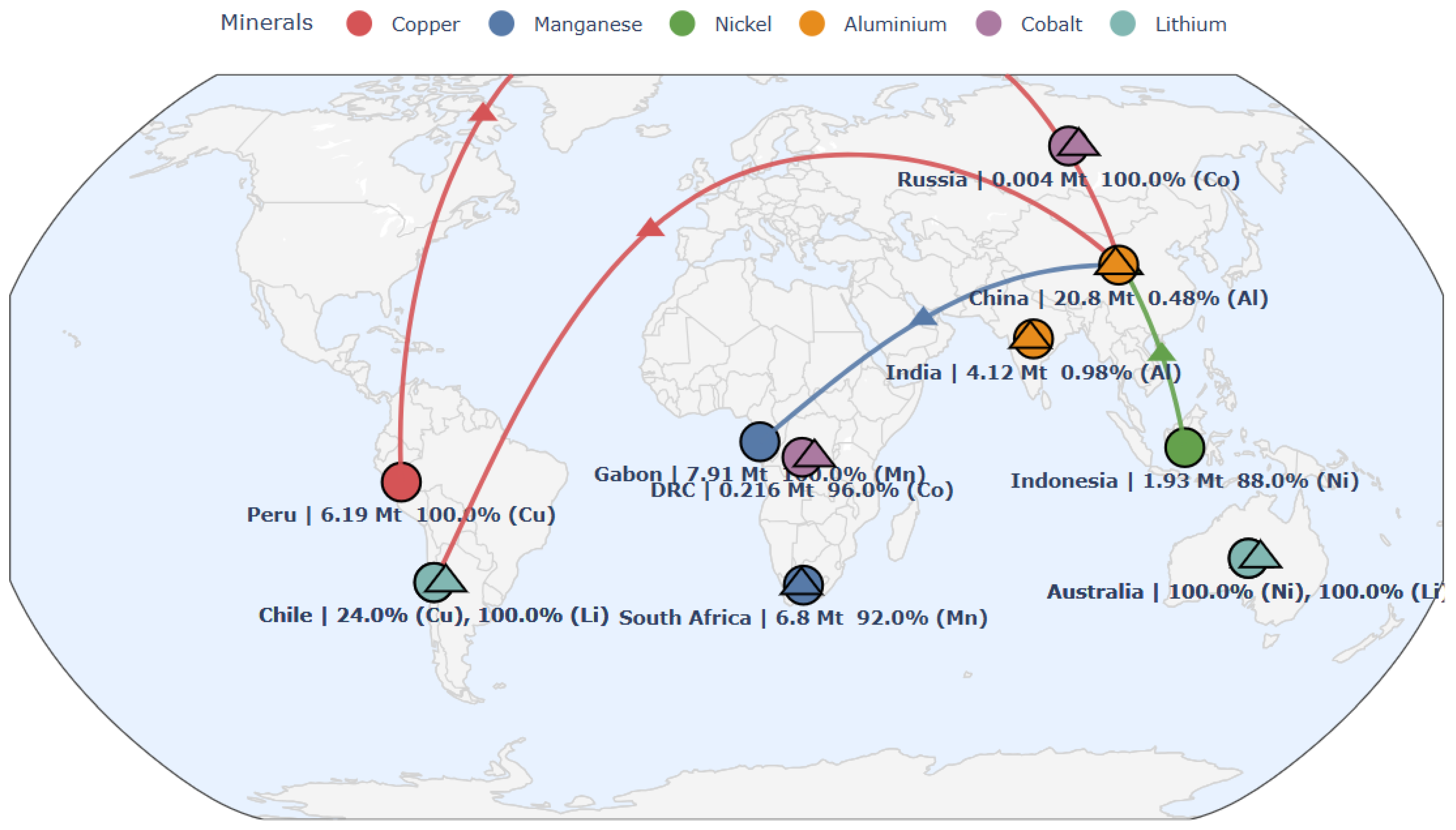

Figure 1 shows the top two producing countries for each mineral (colors correlate to the minerals) and the corresponding top processing location (triangles) for each producer.

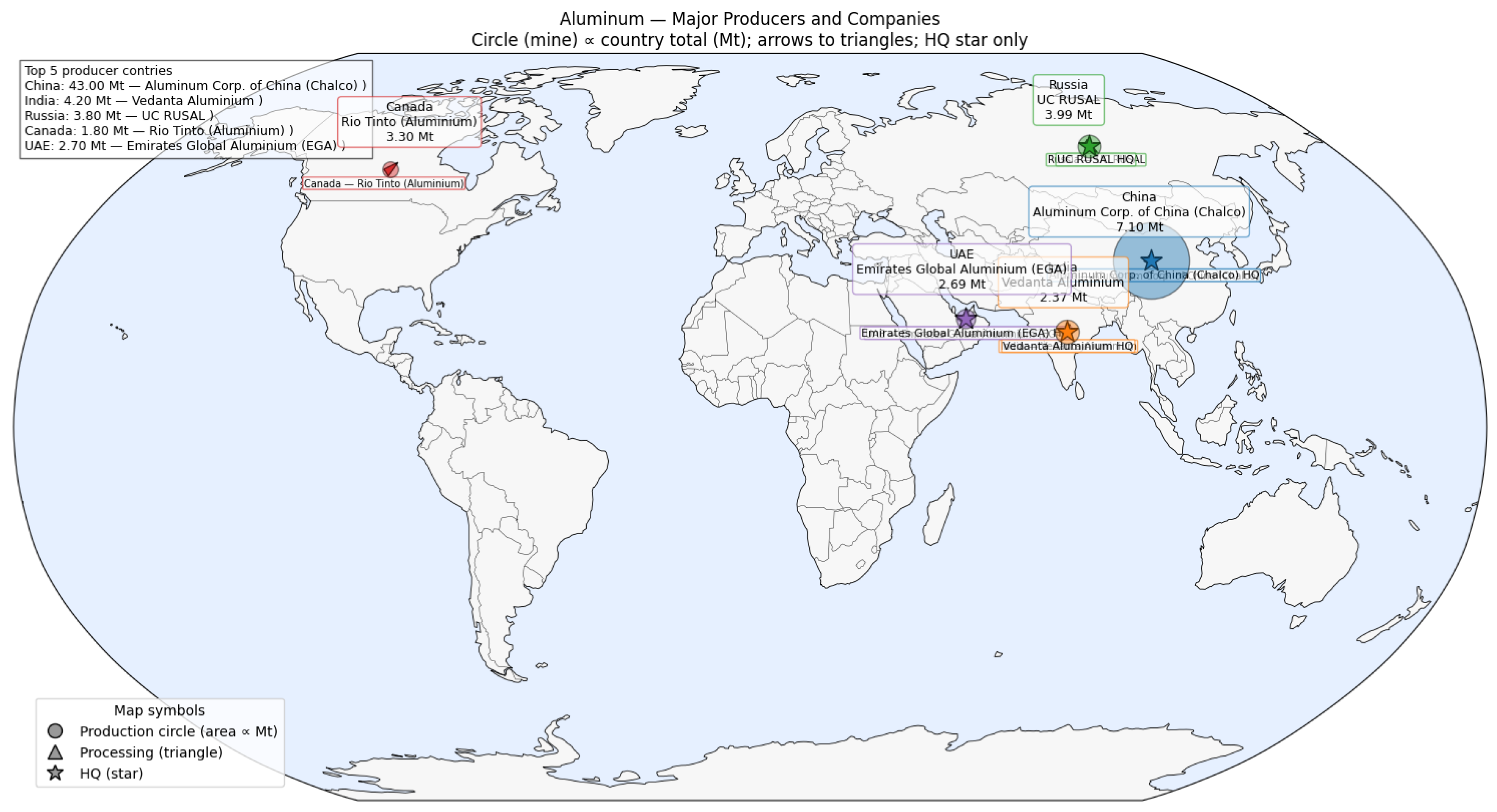

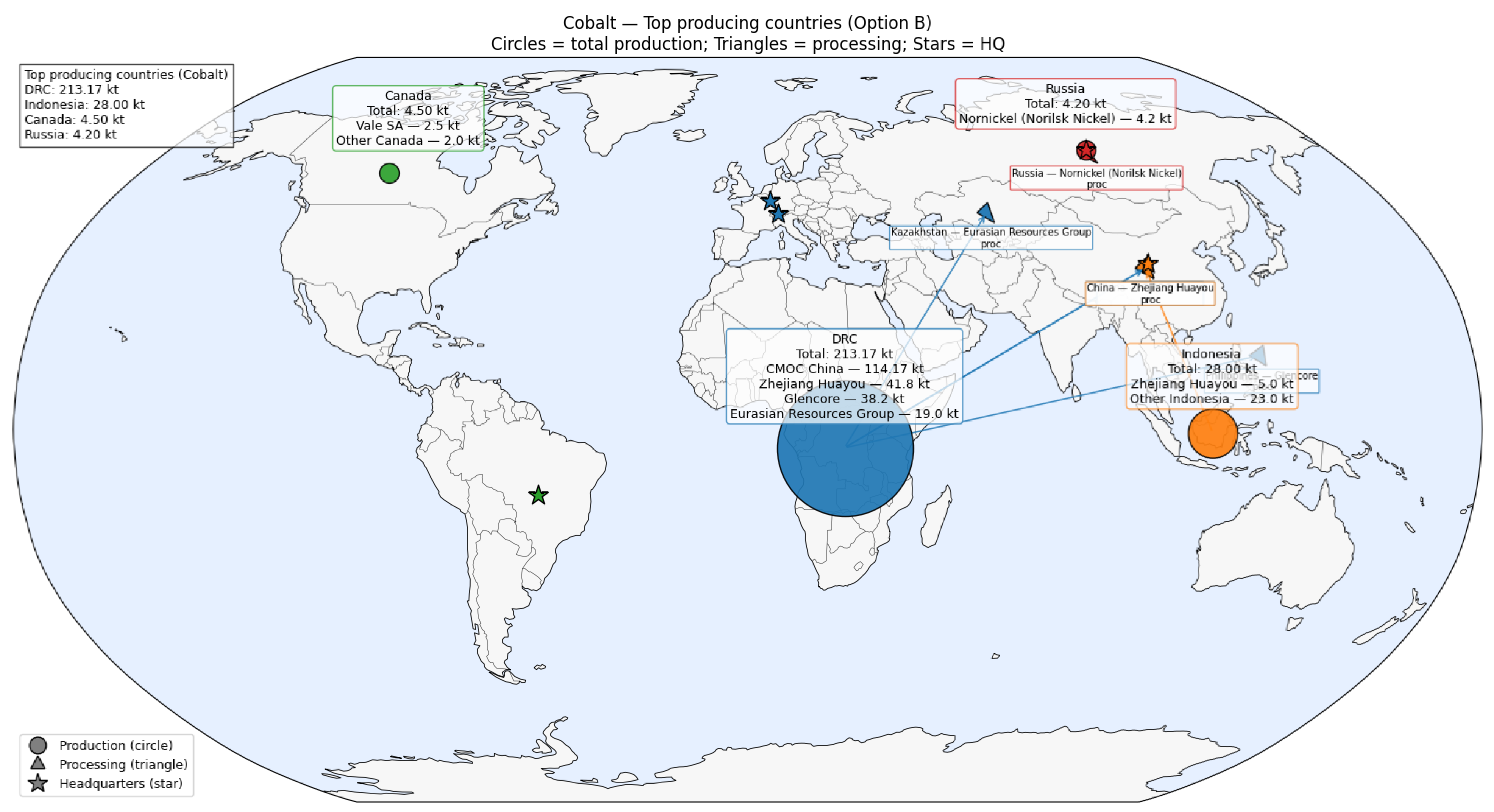

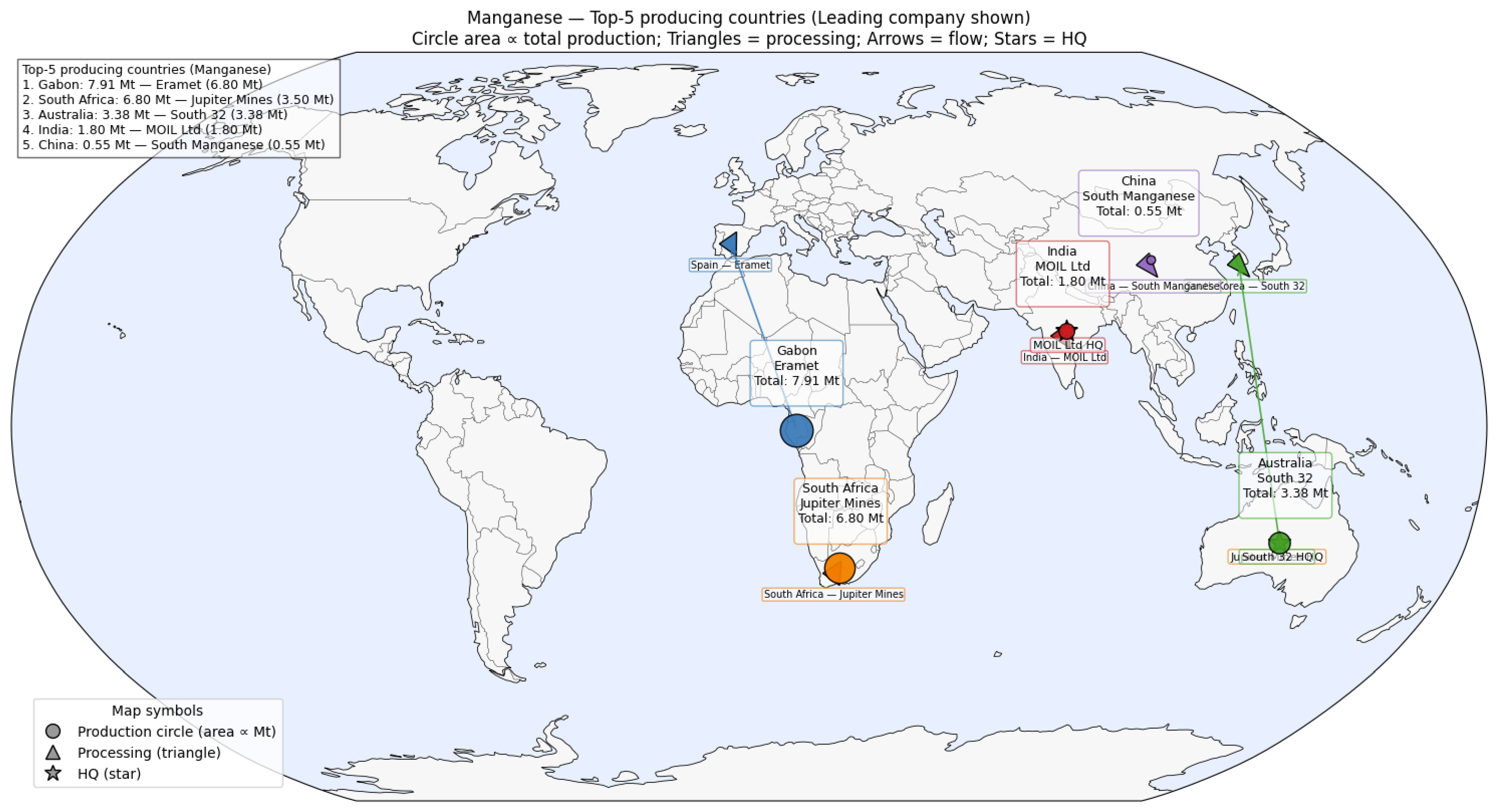

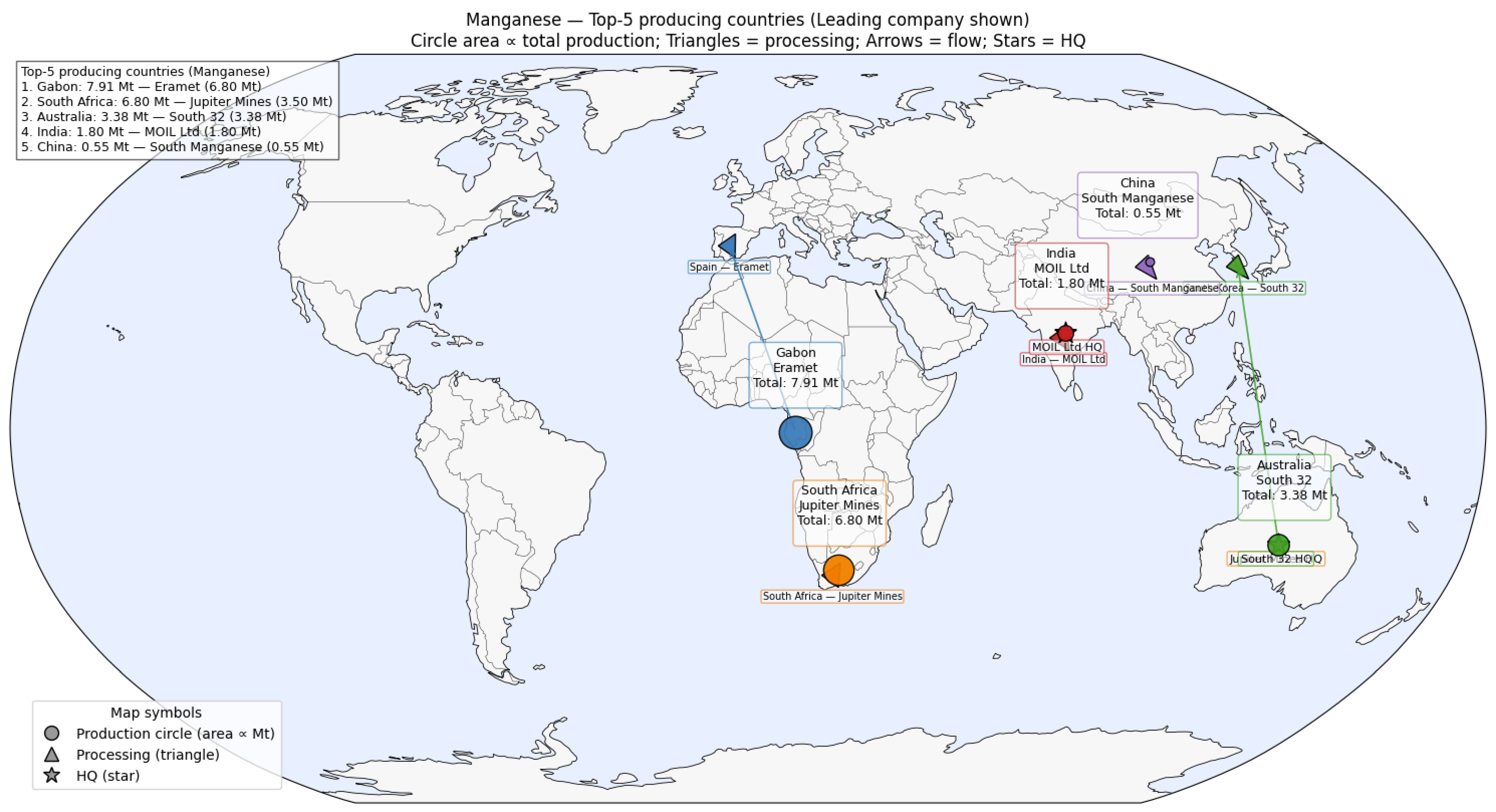

Figure 2,

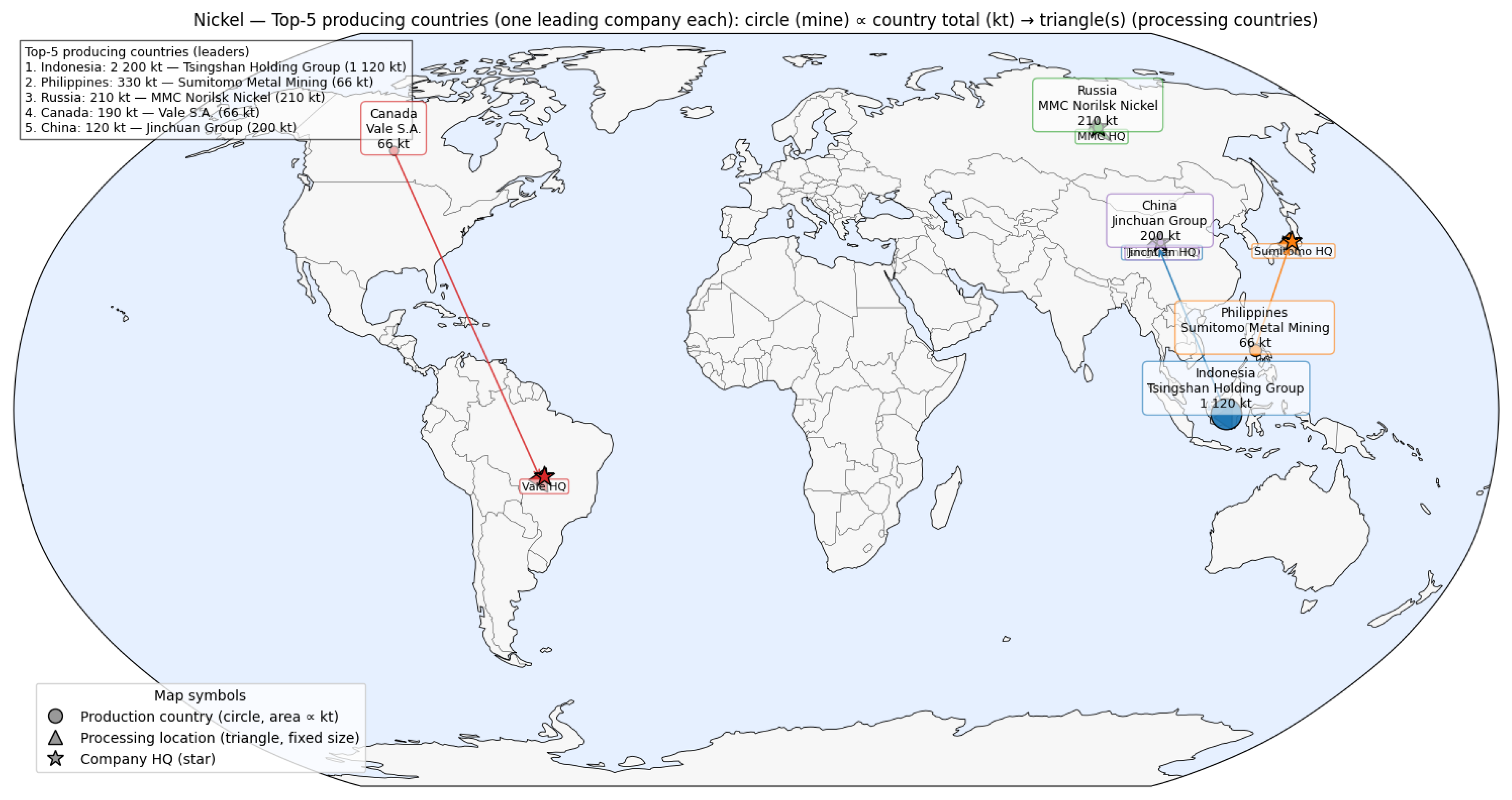

Figure 3,

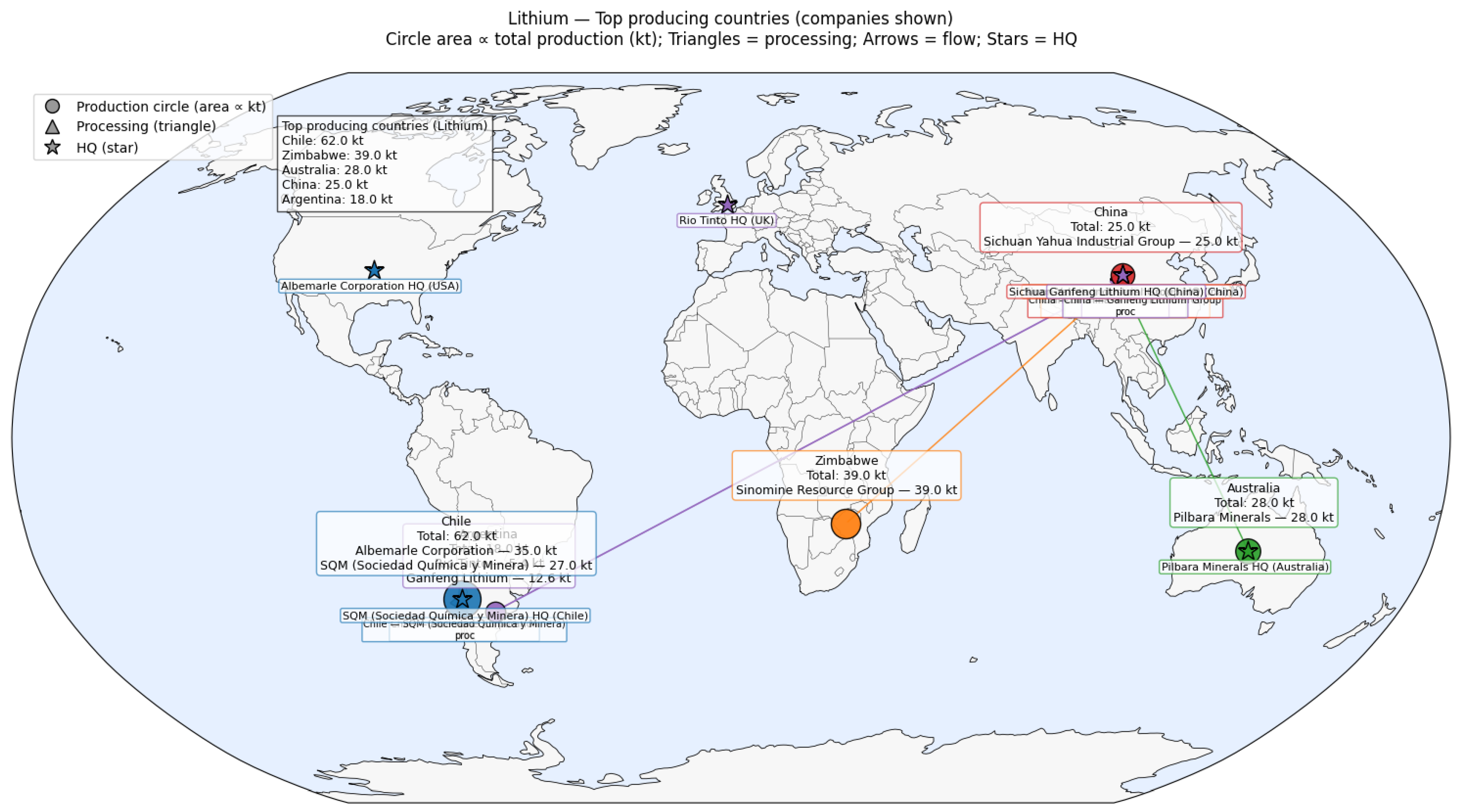

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the top five producers for each respective mineral, their production locations (circle with bigger circles indicating more production), and their company headquarters (star) for mine production of aluminum, nickel, lithium, cobalt, copper, and manganese, respectively. The single mineral maps also show the main processing locations (triangle) where each company sends their ore to be processed. Some companies process their ore on site or within the country while others ship their ore to be processed at another location in the globe. The mineral production data is quantitative, extracted from numerous data sources including company reports, governmental data collection agencies, and other research studies. In contrast, the producer locations are qualitative; they are derived from company reports, major facility locations, and other research studies but the exact flows from mine to processing plant have not been determined in this work. Nonetheless, the maps and tables provide a clear look at who are the major players in the critical mineral space, what are these players mining, where are they mining, and where are they sending their ore to be processed. This information aims to be a useful resource for researchers and policymakers seeking to understand and improve the critical mineral supply chain.

4.1. Aluminum

Table 1 shows that primary aluminum production is heavily concentrated among a small number of vertically integrated corporations.

Figure 2 visualizes the flows from production to processing on a global map. The updated country–company mapping highlights how these firms operate across multiple jurisdictions. Chinese producers such as Chalco, Hongqiao, SPIC, and Xinfa together account for nearly 30% of global supply, while UC RUSAL, Rio Tinto, and EGA also represent significant shares, each spanning both domestic and overseas assets. Additional contributions from India (Vedanta, Hindalco, NALCO), Bahrain (Alba), Norway (Hydro), and the United States (Alcoa, Century) illustrate the broader geographic footprint of the sector, though on a smaller scale. These cross-linked operations underscore the high concentration of production within a limited set of transnational actors.

As seen in

Table 2, primary aluminum production at the country level is highly concentrated in China, where Chalco, Hongqiao, SPIC, and Xinfa collectively represent nearly half of national output. India is another significant contributor, with Vedanta, Hindalco, and NALCO together accounting for the majority of its production. Outside Asia, UC RUSAL dominates Russian supply, while Rio Tinto and Alcoa play major roles across Canada, Australia, and Iceland. Smaller but strategically important contributions come from the Middle East (EGA in the UAE, Alba in Bahrain, and Hydro in Qatar), highlighting the global dispersion of smelting capacity despite heavy regional concentration.

4.2. Nickel

As seen in

Table 3, global nickel production is dominated by Tsingshan Holding Group, which alone accounts for over 30% of the world’s total. Other significant contributors include Huayou Cobalt, Nornickel, Jinchuan Group, and Vale, each supplying between 4 and 10% of global output. A second tier of producers—such as Harita Nickel, Nickel Industries, Glencore, and BHP’s Nickel West—add meaningful shares, while smaller but strategic players like MBMA, SMM, CNGR, Anglo American, South32, and Eramet ensure geographical diversification. Collectively, this distribution underscores both the dominance of Chinese firms in refining and the importance of Indonesia and Australia as rising centers of supply.

As seen in

Table 4, Indonesia dominates global nickel supply, with Tsingshan Holding Group alone providing more than half of the country’s output, while Huayou Cobalt, Nickel Industries, MBMA, Vale, and Harita Nickel contribute significant shares, reflecting the nation’s role as the largest and most diversified hub. Australia follows with production concentrated in BHP’s Nickel West, supported by South32 and Glencore’s Murrin Murrin. New Caledonia remains important through Eramet’s SLN and the Koniambo JV with Glencore, while Canada’s nickel is split mainly between Vale and Glencore. Russia’s Nornickel dominates domestic output entirely, and other contributors include Sumitomo Metal Mining in the Philippines, Jinchuan in China, and Anglo American’s Barro Alto operation in Brazil. This distribution highlights Indonesia’s preeminence, Australia’s consolidation, and the critical but geographically dispersed roles of Canada, Russia, and emerging producers.

4.3. Lithium

Table 5 presents the global lithium production share by major corporations. A few companies dominate the market, with Albemarle (15.99%), Sinomine Resource Group (17.82%), and SQM (12.16%) as the leading producers. Other key contributors include Pilbara Minerals (12.71%), Sichuan Yahua (11.40%), and Ganfeng Lithium (8.10%). Collectively, these firms supply the majority of global lithium, underlining a highly consolidated industry structure.

Table 6 breaks down production at the country–company level. Australia, Chile, and China emerge as the leading producing nations, with company contributions varying widely within each. In Australia, Pilbara Minerals and Mineral Resources together account for more than half of national output, while SQM dominates Chile with over 55%. In China, production is more fragmented, with Sichuan Yahua (53%) and Sinomine (100% of Zimbabwe’s production) reflecting regional concentration. Argentina contributes smaller volumes, divided mainly between Rio Tinto and Ganfeng.

Together, these tables highlight both corporate concentration at the global level and country-level dependence on a few key players, showing how lithium supply is controlled by a limited set of companies across major producing regions.

4.4. Cobalt

Table 7 outlines company-level cobalt production relative to global supply. CMOC China is the leading producer with nearly 40% market share, followed by Zhejiang Huayou (16%) and Glencore (13%). Other firms such as Eurasian Resources Group, Vale, and Nornickel hold smaller shares, while Wheaton Precious Metals and Panoramic Resources remain marginal. Overall, production is concentrated among a few corporations, highlighting structural vulnerabilities in the supply chain.

Table 8 breaks down production by country and company, emphasizing the geographic concentration of cobalt supply. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) dominates global output, with CMOC China, Glencore, and Zhejiang Huayou producing the bulk of its supply. In contrast, countries such as Australia, Cuba, Madagascar, Indonesia, China, Brazil, and Russia contribute smaller volumes, often tied to a single company. This reflects dispersed resources but strong reliance on the DRC, creating chokepoints in both geography and corporate control.

4.5. Copper

As illustrated in

Table 9 and

Table 10, the global copper industry is dominated by major producers such as Volcan Cia Minera from Peru, Freeport-McMoRan from the United States, and BHP Group from Australia, each contributing around 10% of the global market. Other key players include Southern Copper (USA), Yunnan Copper (China), Grupo Mexico (Mexico), Glencore (UK), and Zijin Mining (Hong Kong), with market shares ranging from 4% to 6%. China stands out as the primary processing hub for most of these companies, along with significant refining operations in Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. Overall, while copper production is geographically dispersed, the processing and refining stages are highly concentrated in East Asia, reflecting the global interdependence within the copper supply chain.

As seen in

Table 9 and

Table 10, Peru leads with significant contributions from Volcan, Freeport-McMoRan, BHP, and Southern Copper, jointly accounting for over a third of the country’s total copper output. Chile follows, with production driven by BHP, Freeport-McMoRan, and Glencore, while Australia, Mexico, and the United States also hold major shares in global copper production. Additionally, China, DRC, and Indonesia play important roles, with companies like Yunnan Copper, Zijin Mining, and Glencore actively involved, underscoring the globally distributed yet interconnected nature of copper mining operations.

4.6. Manganese

The data in

Table 11 and

Table 12 detail the major global manganese-producing companies and their market shares. Eramet (France) dominates the industry with 31.38% of global production, with processing spread across Spain, China, the UK, Mexico, and Australia. South32 (Australia), Assmang (South Africa), and Jupiter Mines (Australia) follow as key players, each contributing between 16 and 21% of global output. Other contributors include MOIL Ltd. (India) and South Manganese (Hong Kong), highlighting the geographically diversified yet interlinked structure of global manganese production and processing.

Table 12 highlights major manganese-producing countries and their leading corporations. Gabon leads global production, with Eramet (France) contributing nearly 86% and South Manganese (Hong Kong) accounting for 14% of the country’s total output. South Africa follows, where Assmang (UK), South32 (Australia), and Jupiter Mines (Australia) collectively dominate production, covering over 90% of national output. Australia, India, China, and Malaysia also play key roles, with South32, MOIL Ltd., and Assmang representing full or significant shares of their respective country totals.

4.7. HHI Concentrations

Table 13 illustrates how concentrated the global production of certain critical minerals is, as well as the concentration within the countries that produce the most. We used the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), a standard measure used in economics to determine the degree of market concentration and competition within an industry, to calculate how concentrated the production is. We did not collect data from every single company that produces these minerals, globally or nationally. Instead, we focused only on the largest producers—specifically those with at least a 5–10% market share (either globally or within a leading country).

Because of this, the concentration levels (HHI scores) we calculated are smaller than the true values (underestimates). However, since HHI squares the market share percentages (in order to provide a better indicator of dominance than raw market share), it gives much more weight to companies with larger market shares. This means that the excluded companies with market shares smaller than our 5–10% threshold add very little to the final HHI score. Therefore, our results are still close to the true magnitude, and the conclusions we draw from them remain accurate and useful.

Manganese’s global HHI of approximately 2096 indicates a moderately concentrated market, characterized by dominant production from South Africa (3334), Gabon (7587), and Australia (10,000). These elevated national HHIs suggest that manganese extraction is controlled by a small number of large producers, resulting in limited diversification across the global supply base. The concentration of production within these regions highlights the strategic importance of Southern Africa and Oceania, where vertically integrated operations play a decisive role in shaping global availability and pricing dynamics.

Nickel’s global HHI of approximately 1150 indicates a moderately concentrated market, primarily driven by Indonesia’s dominance in laterite and HPAL operations. At the country level, Indonesia shows a relatively high concentration (2988), while Russia’s HHI of 10,000 reflects a single-producer monopoly. For the Philippines, only one producer—Sumitomo Metal Mining (Japan)—was identified, holding about 20% of national production; no additional company-level data were available. Overall, the results suggest that although global nickel production is moderately competitive, national-level production remains concentrated, with control largely held by a limited number of vertically integrated firms.

Cobalt global HHI of roughly 3214 points to an extremely concentrated market, heavily influenced by Australia (8752), Russia (7198), and China (5830). These high national HHIs reflect a tight supply chain, where a few dominant players maintain significant control over extraction and processing activities. The structure underscores cobalt’s strategic vulnerability, as supply is dependent on limited geographic regions and vertically integrated operations that shape both pricing and availability in the global market.

Lithium global HHI of approximately 1241 reflects a moderately high concentration, consistent with the limited number of nations engaged in large-scale production. The dominance of Zimbabwe (10,000), followed by Argentina (5800) and Chile (4650), highlights a regional clustering of lithium resources within southern Africa and South America. This concentration pattern indicates that while the global market is expanding due to rising battery demand, production control remains confined to a small group of resource-rich countries.

Copper’s global HHI of around 457 reflects a highly competitive and unconcentrated market, with production widely distributed among major producers such as Chile (220), DRC (180), and Peru (2202). The relatively low concentration levels demonstrate that copper supply is diversified across multiple continents, reducing the risk of market dominance by any single country. This dispersed structure enhances supply resilience and market stability, positioning copper as one of the most competitively sourced critical minerals globally.

Aluminum’s global HHI of approximately 312 indicates a highly competitive market, reflecting the wide distribution of production among multiple multinational firms. China’s relatively low HHI of 625 suggests a competitive domestic market structure, even though it accounts for a dominant share of global output. In contrast, India (4258) and Russia (10,000) exhibit significantly higher concentration levels, implying that their national industries are controlled by a smaller number of large producers. Overall, while the global aluminum market appears diverse and competitive, domestic market structures in certain major producing countries remain highly concentrated.

5. Discussion: Supply Chain Narratives

5.1. Aluminum

Aluminum production begins with bauxite mining, which is geographically widespread but increasingly refined through a limited number of industrial hubs. Major bauxite sources are found in Guinea, Australia, China, Brazil, and Indonesia, yet much of the refining into alumina occurs in China, which dominates global output, followed by smaller refining centers in Australia and Brazil. This mismatch between the locations of ore extraction and refining generates large, transoceanic flows of bauxite and alumina, particularly from Guinea and Australia to Chinese facilities. Primary smelting is even more concentrated, shaped by both energy availability and industrial policy. China accounts for roughly three-fifths of world metal output, supported by coal-based power, while hydroelectric capacity supports smelters in Canada, Norway, and Iceland, and natural gas powers those in the Gulf states.

The updated main processing country data show that much of the smelting and refining capacity is concentrated within a few key regions, particularly China and the Middle East, where vertically integrated producers operate across several jurisdictions. Chinese groups such as Chalco, Hongqiao, SPIC, and Xinfa manage both domestic refining and overseas ventures in Guinea and Indonesia, reflecting a strategy of cross-border feedstock security. Outside China, firms such as UC RUSAL, Rio Tinto, Norsk Hydro, Vedanta, and Alcoa operate across multiple continents, illustrating the sector’s global integration. These linkages demonstrate how the apparent geographic diversity in bauxite mining is offset by strong corporate concentration in refining and smelting, where energy access, ownership structure, and regional partnerships ultimately determine supply stability.

When mining and processing occur within the same region, material flows are shorter and more stable. However, the global system still depends heavily on a few high-capacity hubs in East Asia and the Middle East. Disruptions in energy policy, logistics, or raw material supply in these regions can quickly affect the aluminum value chain and global prices, even when mining remains steady. Aluminum’s global HHI of approximately 312 indicates a highly competitive market, reflecting the wide distribution of production among multiple multinational firms. China’s relatively low HHI of 625 suggests a competitive domestic market structure, even though it accounts for a dominant share of global output. In contrast, India (4258) and Russia (10,000) exhibit significantly higher concentration levels, implying that their national industries are controlled by a smaller number of large producers. Overall, while the global aluminum market appears diverse and competitive, domestic market structures in certain major producing countries remain highly concentrated.

5.2. Nickel

Nickel production is increasingly concentrated in Southeast Asia, reflecting a major shift in the global supply landscape. Although ore deposits exist worldwide, Indonesia now leads in both mining and refining, driven by rapid growth of laterite operations and high-pressure acid leach plants. Other producers, including the Philippines, Russia, Canada, Australia, and Brazil, contribute smaller but strategically important shares. The rise of Indonesia has reshaped global supply, linking upstream extraction to midstream processing through industrial parks developed with Chinese partners. The HHI calculations show that a few multinational corporations now dominate this system. Tsingshan Holding Group leads global output through joint ventures connecting Indonesian mines with refining and alloy plants in China. Huayou Cobalt and Jinchuan Group follow similar models, sourcing ore in Indonesia and Africa while refining in China. Russian production remains concentrated under Nornickel, while Vale operates across both Brazil and Indonesia. Multinational firms such as Glencore, BHP, and Eramet maintain diversified operations in Australia, Canada, Norway, and New Caledonia. Together, these patterns highlight the rise of a China–Indonesia production corridor that supplies most of the world’s primary nickel. This structure increases efficiency but also creates regional and corporate risks. Because mining, refining, and precursor processing are concentrated in a few countries and vertically integrated companies, disruptions such as policy changes in Indonesia, sanctions on Russia, or power shortages in East Asia could quickly constrain supply. Nickel supply chains are therefore globally interconnected but also structurally fragile, which has important implications for stainless steel production and electric vehicle battery manufacturing.

5.3. Lithium

The upstream segment of the lithium supply chain exhibits a level of geographic diversity that, at first glance, appears to offer some resilience. Raw lithium is extracted from two primary sources: hard-rock mines in Australia and brine deposits in countries like Chile and Argentina. This extraction is performed by a mix of multinational corporations headquartered in the U.S., Chile, Australia, and China.

However, the analysis of the mineral’s flow reveals a critical point of vulnerability in the midstream. The raw material, whether in the form of spodumene concentrate from Australian mines or brines from South America, is overwhelmingly transported to China for refining and processing into battery-grade chemicals such as lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide. This centralizes a crucial, energy- and capital-intensive stage of the supply chain in one location.

The integration of company-level processing data in

Table 5 clarifies this dependence, showing that while production is led by diversified miners such as Albemarle, SQM, and Pilbara Minerals, the majority of refining is consolidated among Chinese processors including Ganfeng Lithium, Tianqi Lithium, Sinomine Resource Group, and Sichuan Yahua. This firm-level visibility underscores that China’s dominance is not only geographic but also corporate, reflecting the concentration of refining expertise and infrastructure within a few key companies.

The implication of this structure is profound: while the mining operations themselves may be distributed across several countries, a disruption to China’s refining capacity, whether due to trade policies, economic shifts, or domestic energy constraints, would create a ripple effect that cripples the entire global battery manufacturing industry, regardless of the continued flow of raw ore from mines in other nations. This dependency grants China significant strategic leverage over the global market, allowing it to influence prices and supply for downstream industries, including electric vehicle and energy storage manufacturers in the U.S. and Europe, who are racing to build their own battery manufacturing ecosystems.

5.4. Cobalt

The cobalt supply chain is defined by its unique nature as a by-product and its extremely concentrated flow. Unlike lithium, cobalt is rarely mined on its own and is primarily extracted as a secondary product of industrial copper and nickel mining operations. This inherent characteristic links its supply and market dynamics to those of the primary metals. The flow of raw cobalt begins in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which, as the quantitative results showed, is responsible for the vast majority of global extraction. The major corporations that dominate the market, such as CMOC China and Glencore, operate extensive mining assets within the DRC. From the DRC, the flow of cobalt is directed into a highly precarious bimodal pipeline. The raw material is imported almost exclusively by China, which, in 2024, sourced nearly 3 billion USD worth of cobalt from the DRC, representing over 50% of its total cobalt imports. This material is then processed into refined products in Chinese facilities, which control an estimated 72% of the world’s refining capacity. The inclusion of company-level processing information in

Table 7 highlights how a small group of firms, primarily CMOC China, Glencore, Huayou, and Eurasian Resources Group, link extraction in the DRC to refining operations distributed across China and other major hubs. This addition provides clearer visibility into the corporate interdependencies underlying the DRC–China cobalt pipeline. The consequence of this structure is that the global cobalt supply chain is essentially a single, uninterrupted flow from the DRC to China. A disruption at either end of this pipeline, be it political instability, civil conflict, or a policy shift in the DRC, or an economic or regulatory change in China, would create a global crisis for cobalt-dependent industries, including those producing batteries for electric vehicles and portable electronics. This dual concentration introduces an elevated and multi-faceted level of risk that is unique to the cobalt supply chain.

5.5. Copper

Copper usually follows a consistent path worldwide. Ore is mined in many countries across the Americas, Africa, and Oceania. Most ore is processed into concentrate at the mine site and then shipped long distances to large smelting and refining hubs, particularly in East Asia. There, it is converted into blister and subsequently cathode (very pure copper). From cathode, material flows into nearby fabrication plants that produce wire rod, strip, sheets, and cable for power, electronics, and industrial applications.

The main processing country data shows that much of the refining and smelting capacity is concentrated in China, Japan, and South Korea, where firms like Yunnan Copper, Mitsubishi Materials, and LS Corp. process significant volumes of globally mined concentrates. This reflects how copper flows remain globally distributed at the mining stage but increasingly converge toward East Asian processing hubs. The inclusion of partners such as Toyota Tsusho Corp. and Glencore PLC underscores copper’s transnational refining structure and the role of joint ventures in maintaining supply continuity across continents.

Traders often intervene at the concentrate stage to blend materials, match quality to smelter requirements, and manage logistics. The overall pattern is geographically distributed at the start (many countries mine copper) but increasingly concentrated at the smelting, refining, and fabrication stages. This creates dependence on a small number of processing hubs. Disruptions at these hubs—such as policy shifts, port delays, or energy shortages—can quickly affect copper supply and global prices.

When mining and processing occur within the same region, flows are shorter and more stable, though the global system still relies on the major hubs. As copper moves along the chain (concentrate → blister/cathode → finished products), its value and specialization increase, meaning disruptions later in the chain typically cause faster and larger impacts for end users.

5.6. Manganese

Manganese has a well-defined flow. Ore is mined in Southern Africa, Australia, India, and parts of Europe/Asia, then shipped primarily as lumps, fines, or concentrates to alloy plants and refineries. In the alloy route, manganese ore is transformed into ferromanganese (FeMn) and silicomanganese (SiMn), which are used directly in steelmaking to strengthen steel and control impurities. By-products from this process include steel slags and silicon-rich slags, which may be recycled into other processes.

In the refining route, ore (or intermediates) is processed into electrolytic manganese metal (EMM) or high-purity manganese sulfate (HPMSM), both of which are key inputs for battery materials. Some flows also connect to zinc- and aluminum-processing chains, where manganese is used for alloying or recovered from residues.

The processing data highlights how these firms maintain global integration through downstream operations in Spain, China, the United Kingdom, Mexico, and South Korea, where manganese ore is converted into alloys and refined products. Assmang’s joint operations in Malaysia and South32’s collaboration with Korea Zinc Co. Ltd. demonstrate the growing significance of Asian processing centers in transforming raw manganese into high-grade alloys and battery precursors. This spatial pattern shows that while mining remains anchored in Africa and Australia, value addition is increasingly concentrated in industrial hubs across Asia and Europe, reinforcing the asymmetric nature of the manganese supply chain. Downstream, the material divides into two main streams. One goes to steel mills and foundries consuming FeMn/SiMn to produce rebar, sheet, and cast products; these facilities are concentrated in East Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and Europe/North America. The other goes to battery-precursor plants (for NCM chemistries), where high-purity manganese chemicals are combined with nickel and cobalt salts to form cathode precursors.

Overall, manganese supply chains start broadly distributed at the mining stage but become more concentrated at alloy and chemical plants, which serve as hubs for either steel or battery materials. By-products (e.g., slags, silicon metal, residual metals) are sold into other industries or reprocessed to improve recovery.

6. Conclusions

This study quantified the upstream supply of six metals critical to lithium-ion battery technologies—lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, and aluminum—by systematically mapping production across both company and country levels. Using USGS data as a global baseline and reconciling it with company disclosures and Bloomberg outputs, we developed a harmonized dataset that assigns extraction volumes to specific corporations and geographies. The results reveal distinct asymmetries in supply structures: copper and aluminum production remain geographically diverse, while cobalt and manganese are highly concentrated. Nickel and lithium occupy an intermediate position, with expanding production in Indonesia and South America accompanied by increasing dependence on a few midstream processing hubs.

These findings show that supply vulnerabilities arise not only from the distribution of natural resources but also from corporate concentration and midstream bottlenecks. This implies that mining operations, even though they could be distributed across several countries, can be dominated by a few corporations. Even worse, these raw ore is increasingly processed by a few corporations in one region or even one country. Thus, a disruption to a country’s refining capacity, whether due to trade policies, economic shifts, or domestic energy constraints, would create a ripple effect that cripples the entire processing industry, regardless of the continued flow of raw ore from mines in other nations. This dependency could grant dominate corporations or nations significant strategic leverage over the global market, allowing them to influence prices and supply for downstream industries.

Policymakers and industry leaders can apply these insights to target diversification or market share capture where it will have the greatest impact. Upstream investment and partnerships in copper and aluminum can strengthen already diverse supply bases. For nickel and lithium, targeted incentives to expand refining and processing outside current hubs would reduce regional dependency. For cobalt and manganese, risk mitigation through recycling, substitution, or strategic stockpiling may be more effective than expanding primary extraction.

In summary, our work suggests a production and processing policy typology: (1) reinforcement for metals with existing diversity (copper, aluminum); (2) redistribution for those with expanding but concentrated supply and processing (nickel, lithium); and (3) substitution or recycling for highly concentrated materials (cobalt, manganese). This investigation provides a practical guide for prioritizing supply-chain interventions. By presenting a transparent, reproducible dataset anchored in 2024 production, this work establishes both a baseline for future monitoring and a foundation for designing targeted diversification strategies in support of a secure and sustainable energy and critical mineral supply chain.