Accessible Augmented Reality in Sheltered Workshops: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation for Users with Mental Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- How does the perceived usability of a state-of-the-art AR instruction system differ between users with and without mental disabilities in a workplace setting?

- RQ2

- What specific design requirements for AR instructional systems emerge from the feedback of key stakeholders, including both users with mental disabilities and their colleagues and support staff, to address this usability gap and better support cognitive and psychological needs?

2. Related Work

2.1. The Use of Digital Platforms by People with Mental Disabilities

2.2. The Use of AR by People with Cognitive Disabilities

3. Methods

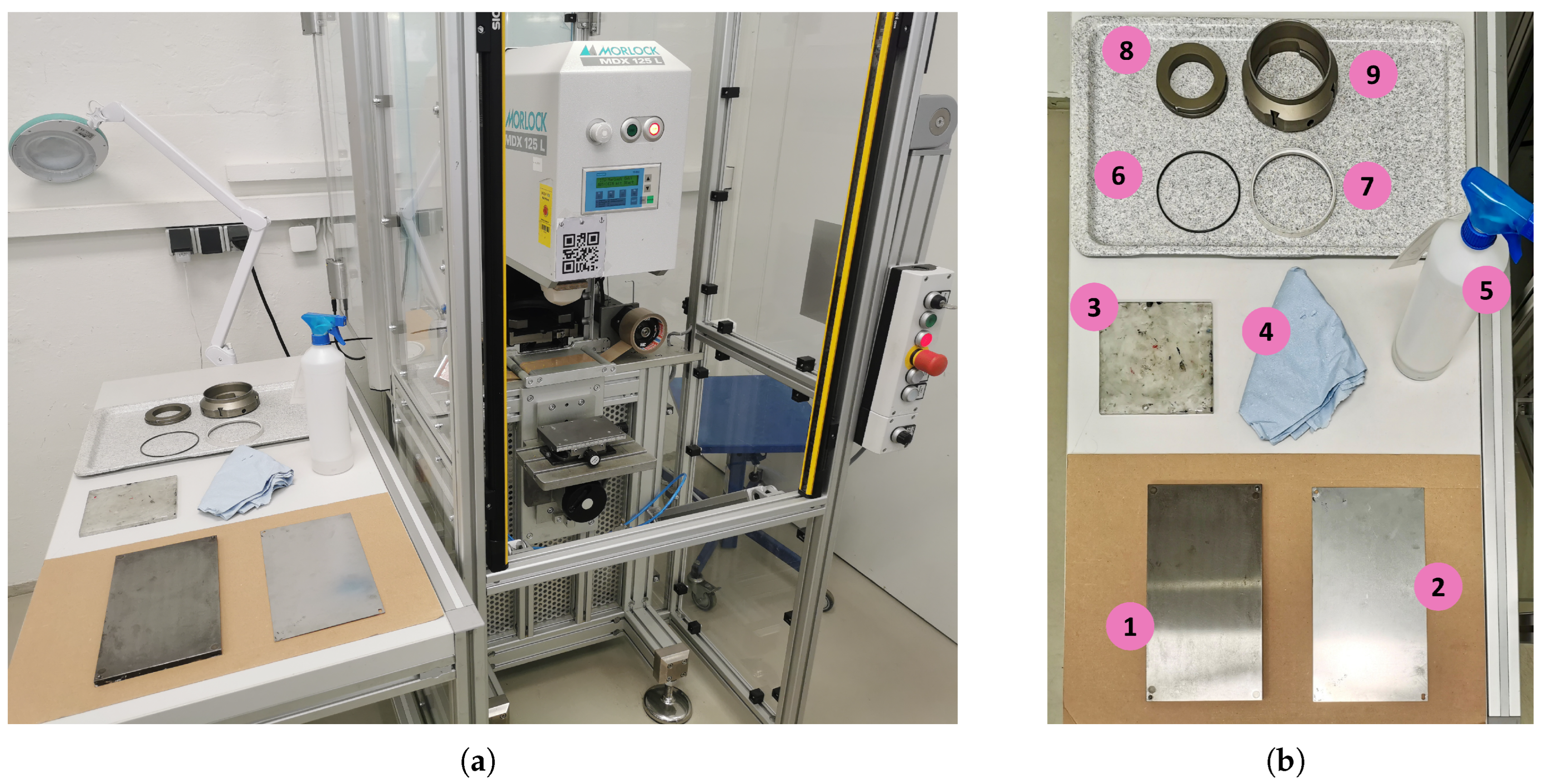

3.1. Use Case

3.2. Participants

3.3. Apparatus

3.4. Procedure

3.5. Analysis

4. Results

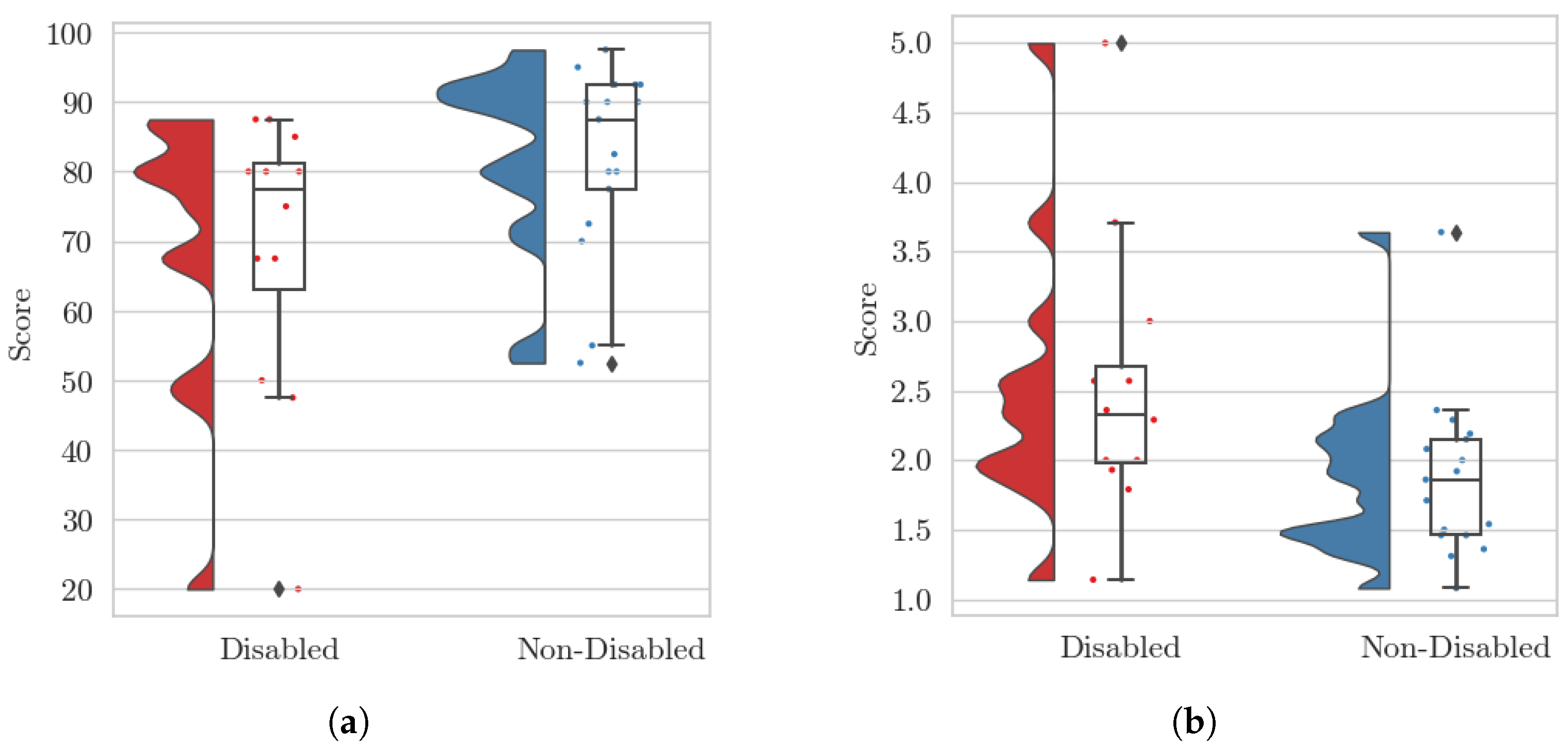

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. Interaction and Navigation

4.2.2. Visual Presentation

4.2.3. System Personalization

4.2.4. User Engagement

4.2.5. User Assistance

5. Discussion

5.1. Users with a Mental Disability Perceive Usability Less Favorably

5.2. Specific User Needs Considering Mental Disability

5.3. Importance of Existing Design Principles

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. In Proceedings of the Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies, Boston, MA, USA, 31 October–4 November 1994; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1995; Volume 2351, pp. 282–292. [Google Scholar]

- Daling, L.M.; Schlittmeier, S.J. Effects of augmented reality-, virtual reality-, and mixed reality–based training on objective performance measures and subjective evaluations in manual assembly tasks: A scoping review. Hum. Factors 2024, 66, 589–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffri, N.F.S.; Rambli, D.R.A. A review of augmented reality systems and their effects on mental workload and task performance. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oun, A.; Hagerdorn, N.; Scheideger, C.; Cheng, X. Mobile Devices or Head-Mounted Displays. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 21825–21839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barteit, S.; Lanfermann, L.; Bärnighausen, T.; Neuhann, F.; Beiersmann, C. Augmented, mixed, and virtual reality-based head-mounted devices for medical education: Systematic review. JMIR Serious Games 2021, 9, e29080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Chen, C.; Teng, Z.; Wang, L. Head-mounted display augmented reality in manufacturing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 83, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Dynamics 365 Guides. Available online: https://www.panasonic.com/jp/business/its/microsoft365/dynamics.html?ipao9700=g&ipao9701=p&ipao9702=microsoft%20dynamics%20365&ipao9703=c&ipao9704=751151782975&ipao9705=&ipao9721=kwd-300349431334&ipao9722=22202204593&ipao9723=172897835725&ipao9724=&ipao9725=9197398&ipao9726=&ipao9727=&ipao9728=&ipao9729=&ipao9730=&ipao9731=&ipao9732=8745681625135215578&ipao9733=&ipao9734=&ipao9735=&ipao9736=&ipao9737=&ipao9738=&ipao9739=&ipao9740=&ipao9741=&utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=google_d365_M&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22202204593&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIievrq4ywkQMVSgZ7Bx2XPQjrEAAYASAAEgL-EfD_BwE (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- PTC. Vuforia. Available online: https://frontline.io/ptc-vuforia-alternative/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=23275936050&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIh6aXyoywkQMV3NIWBR3WtQeXEAAYASAAEgL0-PD_BwE (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- WHO. Mental Disorders. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cavender, A.; Trewin, S.; Hanson, V. General writing guidelines for technology and people with disabilities. SIGACCESS Access. Comput. 2008, 92, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cobigo, V.; Lévesque, D.; Lachapelle, Y.; Mignerat, M. Towards a Functional Definition of Cognitive Disability. 2022; Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Guilera, G.; Pino, O.; Barrios, M.; Rojo, E.; Vieta, E.; Gómez-Benito, J. Towards an ICF Core Set for functioning assessment in severe mental disorders: Commonalities in bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia. Psicothema 2020, 32, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Microsoft. Accessibility—MRTK3. 2022. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/mixed-reality/mrtk-unity/mrtk3-accessibility/packages/accessibility/overview (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Apple. Accessibility. 2024. Available online: https://www.apple.com/accessibility/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Meta. Learn About Accessibility Features for Meta Quest. 2025. Available online: https://www.meta.com/help/quest/674999931400954/?srsltid=AfmBOorigJwgsjpoxGegNGCNJVpZsEq_6Pj_zV3ymretLvXfVQaAPZJX (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Li, Y.; Kim, K.; Erickson, A.; Norouzi, N.; Jules, J.; Bruder, G.; Welch, G.F. A Scoping Review of Assistance and Therapy with Head-Mounted Displays for People Who Are Visually Impaired. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2022, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.; Leite Junior, A.J.M.; Marçal, E.; Viana, W. AR in education for people who are deaf or hard of hearing. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 23, 1483–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzotto, F.; Matarazzo, V.; Messina, N.; Gelsomini, M.; Riva, C. Improving Museum Accessibility through Storytelling in Wearable Immersive VR. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd DigitalHERITAGE, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–30 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Besserer, D.; Sejunaite, K.; Schuler, A.; Riepe, M.; Rukzio, E. cARe: An AR support system for geriatric inpatients with mild cognitive impairment. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Pisa, Italy, 26–29 November 2019; MUM ’19. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbach, N.; Gulde, P.; Armstrong, A.R.; Hartig, L.; Abdelrazeq, A.; Schröder, S.; Neuse, J.; Grimmer, T.; Diehl-Schmid, J.; Hermsdörfer, J. An augmented reality approach for ADL support in Alzheimer’s disease. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltokorpi, J.; Hoedt, S.; Colman, T.; Rutten, K.; Aghezzaf, E.H.; Cottyn, J. Manual assembly learning, disability, and instructions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7903–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, M.; Luxenburger, A.; Knoch, S.; Alexandersson, J. PARTAS. In Proceedings of the 15th PETRA, Corfu, Greece, 29 June–1 July 2022; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, L.S.; Zanardi, I.; Mastrogiuseppe, M.; Span, S.; Landoni, M. “Is This Real?”. In Proceedings of the Universal Access in HCI, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023; pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kešelj, A.; Topolovac, I.; Kačić-Barišić, M.; Burum, M.; Car, Z. Design and Evaluation of an Accessible Mobile AR Application for Learning About Geometry. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th ConTel, Zagreb, Croatia, 30 June–2 July 2021; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeele, V.V.; Schraepen, B.; Huygelier, H.; Gillebert, C.; Gerling, K.; Van Ee, R. Immersive Virtual Reality for Older Adults: Empirically Grounded Design Guidelines. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2021, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisapour, M.; Cao, S.; Domenicucci, L.; Boger, J. Participatory Design of a Virtual Reality Exercise for People with Mild Cognitive Impairment. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweileh, W. Analysis and mapping of scientific literature on virtual and augmented reality technologies used in the context of mental health disorders (1980–2021). J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2023, 18, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, C.N.; Abbas, S.O.; Sever, E.; Özcan Morey, A.; Aslan Genc, H.; Mutluer, T. Use of augmented reality in mental health-related conditions: A systematic review. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231203649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCue, M.; Khatib, R.; Kabir, C.; Blair, C.; Fehnert, B.; King, J.; Spalding, A.; Zaki, L.; Chrones, L.; Roy, A.; et al. User-Centered Design of a Digitally Enabled Care Pathway in a Large Health System: Qualitative Interview Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e42768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, K.; Russell, J.K.; Ryan, B.; Brown, R.L.; Joynt, T.; Uhlmann, L.R.; Smith, G.E.; Donovan, C.; Hides, L.; Spence, S.H.; et al. Co-designing a digital mental health platform, “Momentum”, with young people aged 7–17: A qualitative study. Digit. Health 2023, 9, 20552076231216410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Kim, B.; Han, K. “I Don’t Know Why I Should Use This App”: Holistic Analysis on User Engagement Challenges in Mobile Mental Health. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 26 April–1 May 2025. CHI ’25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Gulliksen, J.; Lantz, A. Cognitive Accessibility for Mentally Disabled Persons. In Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction—INTERACT, Bamberg, Germany, 14–18 September 2015; Abascal, J., Barbosa, S., Fetter, M., Gross, T., Palanque, P., Winckler, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 418–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhataeva, Z.; Akhmetov, T.; Varol, H.A. Augmented Reality for Cognitive Impairments. In Springer Handbook of Augmented Reality; Nee, A.Y.C., Ong, S.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 765–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattgerste, J.; Renner, P.; Pfeiffer, T. Augmented reality action assistance and learning for cognitively impaired people: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, New York, NY, USA, 12–15 July 2019; PETRA ’19. pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, M.; Kosch, T.; Kettner, R.; Korn, O.; Schmidt, A. motionEAP: An Overview of 4 Years of Combining Industrial Assembly with Augmented Reality for Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Knowledge Technologies and Data-Driven Business, Graz, Austria, 18–19 October 2016; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Koushik, V.; Kane, S.K. Towards augmented reality coaching for daily routines. Int. J.-Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2022, 165, 102862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Dudley, J.J.; Garaj, V.; Kristensson, P.O. Inclusivity Requirements for Immersive Content Consumption. In Design for Sustainable Inclusion; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). XR Accessibility User Requirements. 2021. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/xaur/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Brooke, j. SUS: A ‘Quick and Dirty’ Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.R. Psychometric Evaluation of the Post-Study System Usability Questionnaire: The PSSUQ. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1992, 36, 1259–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, K.; Schäffer, J. SUS—An Improved German Translation. 2016. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160330062546/http://minds.coremedia.com/2013/09/18/sus-scale-an-improved-german-translation-questionnaire/#6 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rummel, B. System Usability Scale (Translated into German). 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272830038_System_Usability_Scale_Translated_into_German (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Rauer, M. Quantitative Usablility-Analysen mit der SUS. 2011. Available online: https://seibert.group/blog/2011/04/11/usablility-analysen-system-usability-scale-sus/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Putnam, C.; Puthenmadom, M.; Cuerdo, M.A.; Wang, W.; Paul, N. Adaptation of the System Usability Scale for User Testing with Children. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 25–30 April 2020; CHI EA ’20. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatsareas, P. Semi-structured interviews. In Research Methods in Language Attitudes; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzblatt, K.; Wendell, J.B.; Wood, S. Rapid Contextual Design: A How-To Guide to Key Techniques for User-Centered Design. Ubiquity 2005, 2005, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J.R. Quantifying the User Experience: Practical Statistics for User Research, 1st ed.; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Poggiali, D.; Whitaker, K.; Marshall, T.R.; van Langen, J.; Kievit, R.A. A multi-platform tool for robust data visualization. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, T. The 5S’s: Five Keys to a Total Quality Environment. 1991. Available online: https://www.amazon.com.au/5Ss-Five-Total-Quality-Environment/dp/9283311159 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Edwards, A.L. The relationship between the judged desirability of a trait and the probability that the trait will be endorsed. J. Appl. Psychol. 1953, 37, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P. Product design and apparent usability. The influence of novelty in product appearance. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, G.; Feng, Y.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Gafinowitz, N. Beyond novelty effect: A mixed-methods exploration into the motivation for long-term activity tracker use. JAMIA Open 2019, 2, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, M.; Thieme, A.; Marques, R.; Massiceti, D.; Cutrell, E.; Morrison, C. A Dynamic AI System for Extending the Capabilities of Blind People. In Proceedings of the CHI EA ’20: Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020. CHI EA ’20. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameswaran, V.; J. Fiannaca, A.; Kneisel, M.; Karlson, A.; Cutrell, E.; Ringel Morris, M. Understanding In-Situ Use of Commonly Available Navigation Technologies by People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 22nd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Athens, Greece, 26–28 October 2020. ASSETS ’20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Junuzovic, S.; Ofek, E.; Sinclair, M.; Porter, J.R.; Yoon, C.; Machanavajhala, S.; Ringel Morris, M. Towards Sound Accessibility in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Montréal, QC, Canada, 18–22 October 2021; ICMI ’21. pp. 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Junuzovic, S.; Ofek, E.; Sinclair, M.; Porter, J.; Yoon, C.; Machanavajhala, S.; Ringel Morris, M. A Taxonomy of Sounds in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Virtual, 28 June–2 July 2021; DIS ’21. pp. 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, R.L.; Junuzovic, S.; Mott, M. Nearmi: A Framework for Designing Point of Interest Techniques for VR Users with Limited Mobility. In Proceedings of the 23rd International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Virtual, 22–25 October 2021. ASSETS ’21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, J.; Junuzovic, S.; Devine, J.; Porter, J.; Mott, M. Understanding How People with Limited Mobility Use Multi-Modal Input. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022. CHI ’22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, R.; Santos, A.; Marques, B.; Ferreira, C.; Almeida, D.; Ramalho, P.; Batista, J.; Dias, P.; Santos, B.S. Pervasive Augmented Reality to support logistics operators in industrial scenarios: A shop floor user study on kit assembly. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 1631–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouot, M.; Le Bigot, N.; Bricard, E.; Bougrenet, J.L.d.; Nourrit, V. Augmented reality on industrial assembly line: Impact on effectiveness and mental workload. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 103, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, H.; Martinez, S.; Paelke, V.; Röcker, C. Head-Mounted Displays in Industrial AR-Applications: Ready for Prime Time? In HCI in Business, Government, and Organizations; Nah, F.F.H., Xiao, B.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Meixner, G. Gamified AR Training for an Assembly Task. In Proceedings of the 2019 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Leipzig, Germany, 1–4 September 2019; pp. 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, O.; Funk, M.; Schmidt, A. Towards a gamification of industrial production: A comparative study in sheltered work environments. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGCHI Symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems, Duisburg, Germany, 23–26 June 2015; EICS ’15. pp. 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.T.; Plakas, G.; Agalianos, K.; Aretoulaki, E.; Gayialis, S.P.; Andrianopoulos, A. Augmented Reality and Gamification to Increase Productivity and Job Satisfaction in the Warehouse of the Future. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.W.S.; Davenport, T.; Johnson, D.; Vella, K.; Hickie, I.B. Gamification in Apps and Technologies for Improving Mental Health and Well-Being: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e13717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Qian, X.; He, F.; Hu, X.; Huo, K.; Cao, Y.; Ramani, K. CAPturAR: An Augmented Reality Tool for Authoring Human-Involved Context-Aware Applications. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Misc and Technology, Virtual, 20–23 October 2020; UIST ’20. pp. 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Fang, W.; Gao, S.; Hong, J.; Chen, Y. Edge computing-driven scene-aware intelligent augmented reality assembly. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 7369–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blattgerste, J.; Renner, P.; Pfeiffer, T. Authorable augmented reality instructions for assistance and training in work environments. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Pisa, Italy, 27–29 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dünser, A.; Grasset, R.; Seichter, H.; Billinghurst, M. Applying HCI Principles to AR Systems Design. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop at the IEEE Virtual Reality 2007 Conference, Charlotte, NC, USA, 11 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wuttke, L.; Bühler, C.; Klug, A.K.; Söffgen, Y. Testing an AR Learning App for People with Learning Difficulties in Vocational Training in Home Economics. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuri, F.; Pizzigalli, A.; Sanna, A. A State Validation System for Augmented Reality Based Maintenance Procedures. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanta, M.H.; Sarode, A.; George, K. Error detection using augmented reality in the subtractive manufacturing process. In Proceedings of the 2020 10th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2020; pp. 0592–0597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanescu, A.; Mohr, P.; Thaler, F.; Kozinski, M.; Skreinig, L.R.; Schmalstieg, D.; Kalkofen, D. Error Management for Augmented Reality Assembly Instructions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S. Towards a Framework to Understand Mental and Cognitive Accessibility in a Digital Context. Ph.D. Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.; Li, X. Characterization and Optimization of Field of View in a Holographic Waveguide Display. IEEE Photonics J. 2017, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov-Vetter, D.; Luboschik, M.; Islam, A.T.; Gauger, P.; Staadt, O. The Effect of Spatial Reference on Visual Attention and Workload during Viewpoint Guidance in Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Symposium on Spatial User Interaction, Virtual, 30 October–1 November 2020; SUI ’20. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, A.; Trepkowski, C.; Eibich, T.D.; Maiero, J.; Kruijff, E.; Schöning, J. Comparing Non-Visual and Visual Guidance Methods for Narrow Field of View Augmented Reality Displays. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 3389–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.E.C.; Polvi, J.; Taketomi, T.; Yamamoto, G.; Sandor, C.; Kato, H. Toward Standard Usability Questionnaires for Handheld Augmented Reality. IEEE Comput. Graph. Appl. 2015, 35, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Clean print and base plate |

| 2 | Place print onto base plate |

| 3 | Place ceramic ring onto plastic plate |

| 4 | Insert sealing ring into ceramic ring |

| 5 | Place ink cup onto ceramic ring |

| 6 | Check cup and ring for even gap |

| 7 | Insert magnet into ink cup |

| 8 | Configure magnet to weakest level |

| 9 | Align print plate |

| 10 | Place ink cup onto print plate |

| 11 | Sway ink cup across print plate |

| 12 | Enable setup mode |

| 13 | Start up machine |

| 14 | Switch machine to manual mode |

| 15 | Bring forward print sled |

| 16 | Fold up cup holder |

| 17 | Insert print plate into machine |

| 18 | Fasten print plate |

| 19 | Fold down cup holder |

| 20 | Confirm operability by moving print sled |

| No. | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is your general impression of the system? |

| 2 | In terms of interacting with the system, what did you like, what didn’t you like? |

| 3 | In terms of presentation of content, what did you like, what didn’t you like? |

| 4 | Did you experience any problems during the machine setup task? |

| 5 | Did anything contribute particularly positively to your experience? |

| 6 | Did anything contribute particularly negatively to your experience? |

| 7 | Do you have suggestions for improving the system? |

| Measure | Dimension | D | ND | p | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUS | Overall | 68.96 (20.38) | 82.21 (13.28) | 0.025 * | 0.997 |

| PSSUQ | Overall | 2.43 (0.97) | 1.82 (0.16) | 0.043 * | 0.779 |

| System Usability (SU) | 2.50 (1.26) | 1.62 (0.49) | 0.014 * | 0.993 | |

| Information Quality (IMQ) | 2.62 (0.91) | 2.25 (0.98) | 0.325 | 0.393 | |

| Interface Quality (IFQ) | 1.99 (0.97) | 1.54 (0.55) | 0.180 | 0.595 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Knoben, V.; Stellmacher, M.; Blattgerste, J.; Hein, B.; Wurll, C. Accessible Augmented Reality in Sheltered Workshops: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation for Users with Mental Disabilities. Virtual Worlds 2026, 5, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds5010001

Knoben V, Stellmacher M, Blattgerste J, Hein B, Wurll C. Accessible Augmented Reality in Sheltered Workshops: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation for Users with Mental Disabilities. Virtual Worlds. 2026; 5(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds5010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnoben, Valentin, Malte Stellmacher, Jonas Blattgerste, Björn Hein, and Christian Wurll. 2026. "Accessible Augmented Reality in Sheltered Workshops: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation for Users with Mental Disabilities" Virtual Worlds 5, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds5010001

APA StyleKnoben, V., Stellmacher, M., Blattgerste, J., Hein, B., & Wurll, C. (2026). Accessible Augmented Reality in Sheltered Workshops: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation for Users with Mental Disabilities. Virtual Worlds, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/virtualworlds5010001