Producing Altered States of Consciousness, Reducing Substance Misuse: A Review of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, Transcendental Meditation and Hypnotherapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

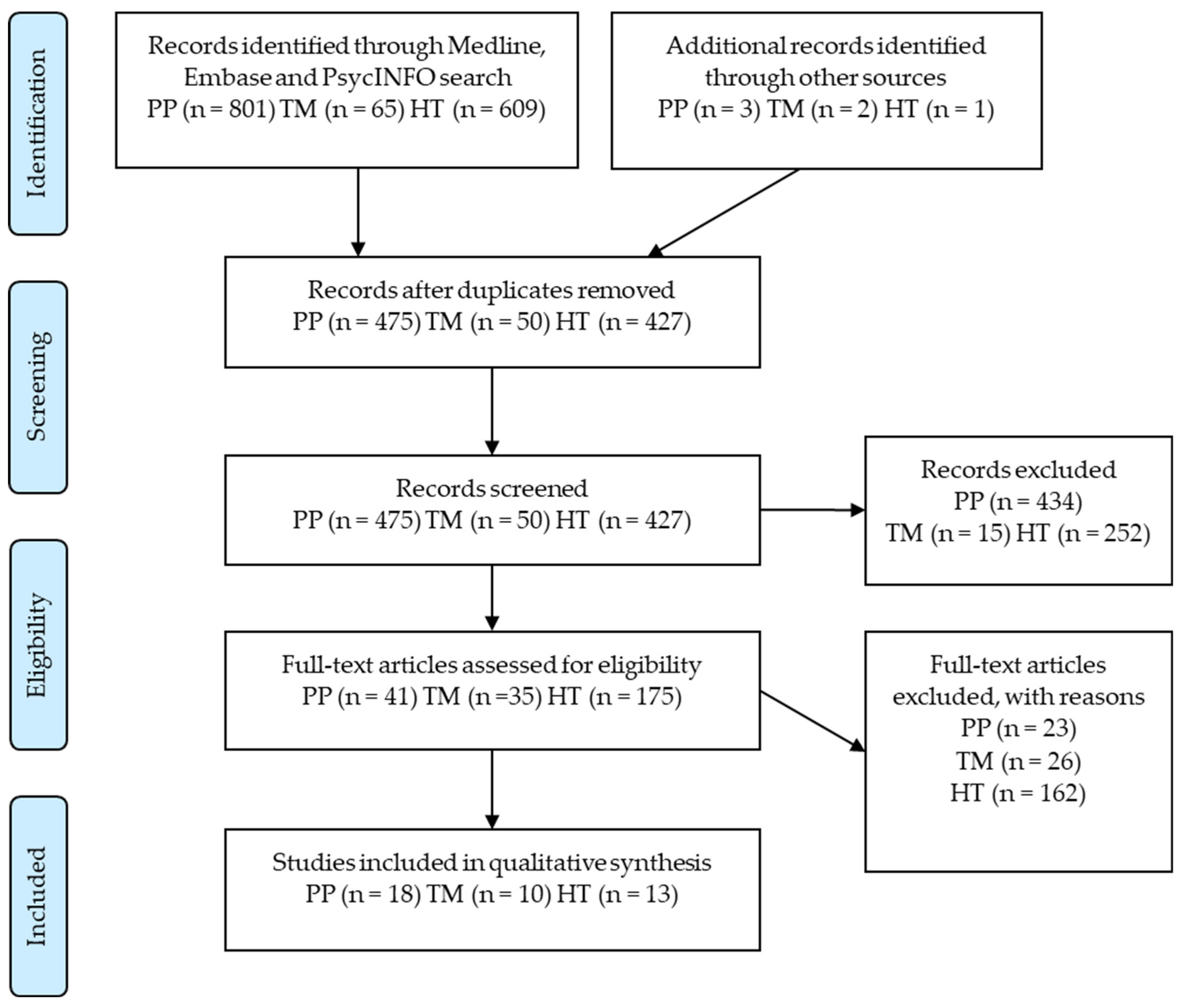

- Two authors (ADS, PP) scanned titles and abstracts of all articles in search results, independently applying eligibility criteria. Reference lists of included papers were scanned, and an additional six papers were found and manually added. A total of 41 articles that met the inclusion criteria were identified across the three treatment approaches.

- For each included trial, data were extracted independently by the authors. Substance use and abstinence results based on biochemical markers or self-reports were accepted. Quantitative and qualitative reports on biopsychosocial outcomes were extracted from results and discussion sections. Included studies, extracted data and study limitations were compared, and any discrepancies resolved through consensus decision making.

3. Results

3.1. Psychedelic Assisted Psychotherapy

3.1.1. PP Outcomes

3.1.2. PP Limitations

3.2. Transcendental Meditation

3.2.1. TM Outcomes

3.2.2. TM Limitations

3.3. Hypnotherapy

3.3.1. HT Outcomes

3.3.2. HT Limitations

4. Discussion

4.1. Substance Misuse Treatment Efficacy

4.2. Biopsychosocial Benefits

4.3. Study Quality and Limitations

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Volkow, N.D.; Koob, G.F.; McLellan, A.T. Neurobiologic advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.A. Effectiveness of the Transcendental Meditation Program in Criminal Rehabilitation and Substance Abuse Recovery. J. Offender Rehabil. 2003, 36, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.E. Psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 2016, 68, 264–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthing, G.W. The Psychology of Consciousness; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tart, C. The ”High” dream: A new state of consciousness. In Altered States of Consciousness: A Book of Readings; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, A.M. Altered states of consciousness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1966, 15, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, G. Consciousness: The remembered present. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 929, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaitl, D.; Birbaumer, N.; Gruzelier, J.; Jamieson, G.A.; Kotchoubey, B.; Kübler, A.; Lehmann, D.; Miltner, W.H.R.; Ott, U.; Pütz, P.; et al. Psychobiology of Altered States of Consciousness. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 98–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovic, D.; Cosic, I. Sleep Onset Process as an Altered State of Consciousness. In States of Consciousness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzner, R. Addiction and transcendence as altered states of consciousness. J. Transpers. Psychol. 1994, 26, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tassi, P.; Muzet, A. Defining the states of consciousness. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2001, 25, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Romeu, A.; Richards, W.A. Current perspectives on psychedelic therapy: Use of serotonergic hallucinogens in clinical interventions. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonaro, T.M.; Bradstreet, M.P.; Barrett, F.S.; Maclean, K.A.; Jesse, R.; Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: Acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, B.E.; Singer, T. Phenomenological fingerprints of four meditations: Differential state changes in affect, mind-wandering, meta-cognition, and interoception before and after daily practice across 9 months of training. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, F.; Shear, J. Focused attention, open monitoring and automatic self-transcending: Categories to organize meditations from Vedic, Buddhist and Chinese traditions. Conscious. Cogn. 2010, 19, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, D. Creating Health: Beyond Prevention, toward Perfection; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH): Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, H.; Wallace, R.K. Decreased drug abuse with Transcendental Meditation: A study of 1862 subjects. In Proceedings of the Drug Abuse: Proceedings of the International Conference, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 9–13 November 1970; pp. 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzenhoffer, A.M. Scales, scales and more scales. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2002, 44, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendy, K. Placebo problems: Boundary work in the psychedelic science renaissance. In Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Cosimano, M.; Griffiths, R. Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 28, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2017, 43, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Forcehimes, A.A.; Pommy, J.A.; Wilcox, C.E.; Barbosa, P.C.R.; Strassman, R.J. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: A proof-of-concept study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 29, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakwar, E.; Levin, F.; Hart, C.L.; Basaraba, C.; Choi, J.; Pavlicova, M.; Edward; Nunes, V. A Single Ketamine Infusion Combined With Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Alcohol Use Disorder: A Randomized Midazolam-Controlled Pilot Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.E. A Treatment Program for Alcoholics in a Mental Hospital. Q. J. Stud. Alcohol 1962, 23, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.K.; Alper, K. Treatment of opioid use disorder with ibogaine: Detoxification and drug use outcomes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2018, 44, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupitsky, E.; Burakov, A.; Romanova, T.; Dunaevsky, I.; Strassman, R.; Grinenko, A. Ketamine psychotherapy for heroin addiction: Immediate effects and two-year follow-up. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2002, 23, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krupitsky, E.; Burakov, A.M.; Dunaevsky, I.V.; Romanova, T.N.; Slavina, T.Y.; Grinenko, A.Y. Single Versus Repeated Sessions of Ketamine-Assisted Psychotherapy for People with Heroin Dependence. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2007, 39, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noller, G.E.; Frampton, C.M.; Yazar-Klosinski, B. Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2018, 44, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C.; McCabe, O.L. Residential psychedelic (LSD) therapy for the narcotic addict: A controlled study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1973, 28, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakwar, E.; Levin, F.; Foltin, R.W.; Nunes, E.V.; Hart, C.L. The Effects of Subanesthetic Ketamine Infusions on Motivation to Quit and Cue-Induced Craving in Cocaine-Dependent Research Volunteers. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, G.; Lucas, P.; Capler, N.; Tupper, K.; Martin, G. Ayahuasca-Assisted Therapy for Addiction: Results from a Preliminary Observational Study in Canada. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2013, 6, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loizaga-Velder, A.; Verres, R. Therapeutic effects of ritual ayahuasca use in the treatment of substance dependence—Qualitative results. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2014, 46, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mash, D.C.; Duque, L.; Page, B.; Allen-Ferdinand, K. Ibogaine Detoxification Transitions Opioid and Cocaine Abusers between Dependence and Abstinence: Clinical Observations and Treatment Outcomes. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2014, 7, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, K.; Stajic, M.; Gill, J. Fatalities temporally associated with the ingestion of ibogaine. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, E.; Capler, R.; Thomas, G.; Lucas, P.; Tupper, K.W. Exploring ayahuasca-assisted therapy for addiction: A qualitative analysis of preliminary findings among an Indigenous community in Canada. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2019, 38, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorani, T.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Swift, T.C.; Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W. Psychedelic therapy for smoking cessation: Qualitative analysis of participant accounts. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Podrebarac, S.K.; Duane, J.H.; Amegadzie, S.S.; Malone, T.C.; Owens, L.T.; Ross, S.; Mennenga, S.E. Clinical Interpretations of Patient Experience in a Trial of Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy for Alcohol Use Disorder. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, R.J. Secondary Prevention of Drug Dependence through the Transcendental Meditation Program in Metropolitan Philadelphias. Int. J. Addict. 1977, 12, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, A. The Role of the Transcendental Meditiation Technique in Promoting Smoking Cessation. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 1994, 11, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.S.; Scarano, T. Transcendental Meditation in the Treatment of Post-Vietnam Adjustment. J. Couns. Dev. 1985, 64, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryczynski, J.; Schwartz, R.P.; Fishman, M.J.; Nordeck, C.D.; Grant, J.; Nidich, S.; Rothenberg, S.; O’Grady, K.E. Integration of Transcendental Meditation® (TM) into alcohol use disorder (AUD) treatment. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2018, 87, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuab, E.; Steiner, S.S.; Weingarten, E.; Walton, K.G. Effectiveness of broad spectrum approaches to relapse prevention in severe alcoholism: A long-term, randomized, controlled trial of transcendental meditiation, EMG biofeedback and electronic neurotherapy. Alcohol. Treat. Q. 1994, 11, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, V.A.; Monto, A.; Williams, J.J.; Rigg, J.L. Impact of Transcendental Meditation on Psychotropic Medication Use Among Active Duty Military Service Members With Anxiety and PTSD. Mil. Med. 2016, 181, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brautigam, E. Effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on drug abusers: A prospective study. Sci. Res. Transcend. Medit. Program Collect. Pap. 1977, 1, 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- Ballou, D. The transcendental meditation program at Stillwater Prison. Sci. Res. Transcend. Medit. Program Collect. Pap. 1977, 1, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Haaga, D.A.F.; Grosswald, S.; Gaylord-King, C.; Rainforth, M.; Tanner, M.; Travis, F.; Nidich, S.; Schneider, R.H. Effects of the Transcendental Meditation Program on Substance Use among University Students. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2011, 2011, 537101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidich, S.I.; Rainforth, M.V.; Haaga, D.A.F.; Hagelin, J.; Salerno, J.W.; Travis, F.; Tanner, M.; Gaylord-King, C.; Grosswald, S.; Schneider, R.H. A Randomized Controlled Trial on Effects of the Transcendental Meditation Program on Blood Pressure, Psychological Distress, and Coping in Young Adults. Am. J. Hypertens. 2009, 22, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahijevych, K.; Yerardl, R.; Nedilsky, N. Descriptive outcomes of the American Lung Association of Ohio hypnotherapy smoking cessation program. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2000, 48, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabasz, A.F.; Baer, L.; Sheehan, D.V.; Barabasz, M. A three-year follow-up of hypnosis and restricted environmental stimulation therapy for smoking. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1986, 34, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Spillmann, M.; Haug, S.; Schaub, M.P. Group hypnosis vs. relaxation for smoking cessation in adults: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hely, J.M.; Jamieson, G.A.; Dunstan, D. Smoking cessation: A combined cognitive behavioural therapy and hypnotherapy self-help treatment protocol. Aust. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2011, 39, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, G.; Beder, B.; Prible, C.R.; Pinney, J. Reducing smoking at the workplace: Implementing a smoking ban and hypnotherapy. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1995, 37, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, G.; Marcus, J.; Bates, J.; Hasan Rajab, M.; Cook, T. Intensive hypnotherapy for smoking cessation: A prospective study. Intl. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2006, 54, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabadi, M.; Taban, H.; Gholamrezaei, A. Hypnotherapy in the Treatment of Opium Addiction: A Pilot Study. Integr. Med. 2012, 11, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, F.M.; Zagarins, S.E.; Pischke, K.M.; Saiyed, S.; Bettencourt, A.M.; Beal, L.; Macys, D.; Aurora, S.; McCleary, N. Hypnotherapy is more effective than nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, G.; Stanley, R.; Burrows, G.; Horne, D. Treatment effectiveness of hypnosis and behaviour therapy in smoking cessation: A methodological refinement. Addict. Behav. 1986, 11, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganiello, A.J. A comparative study of hypnotherapy and psychotherapy in the treatment of methadone addicts. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 1984, 26, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, D.K. Comparison of hypnotherapy with systematic relaxation in the treatment of cigarette habituation. J. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 39, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekala, R.J.; Maurer, R.; Kumar, V.; Elliott, N.C.; Masten, E.; Moon, E.; Salinger, M. Self-hypnosis relapse prevention training with chronic drug/alcohol users: Effects on self-esteem, affect, and relapse. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2004, 46, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestopal, I.; Bramness, J.G. Effect of Hypnotherapy in Alcohol Use Disorder Compared with Motivational Interviewing: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Addict. Disord. Their Treat. 2019, 18, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, T.P.; Duncan, C.; Simon, J.A.; Solkowitz, S.; Huggins, J.; Lee, S.; Delucchi, K. Hypnosis for smoking cessation: A randomized trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008, 10, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, T.P.; Duncan, C.L.; Solkowitz, S.N.; Huggins, J.; Simon, J.A. Hypnosis for smoking relapse prevention: A randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2017, 60, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropley, M.; Ussher, M.; Charitou, E. Acute effects of a guided relaxation routine (body scan) on tobacco withdrawal symptoms and cravings in abstinent smokers. Addiction 2007, 102, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persinger, M.A.; Carrey, N.J.; Suess, L.A. TM and Cult Mania; Christopher Pub. House: North Quincy, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, S.J.; Myer, E.; Mackillop, J. The sysematic study of negative post-hypnotic effects: Research hypnosis, clinical hypnosis and stage hypnosis. Contemp. Hypn. Integr. Ther. 2000, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, G.F. Hypnosis and the relationship between trance, suggestion, expectancy and depth: Some semantic and conceptual issues. Am. J. Clin. Hypn. 2010, 53, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Bossis, A.; Guss, J.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Malone, T.; Cohen, B.; Mennenga, S.E.; Belser, A.; Kalliontzi, K.; Babb, J. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseman, L.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millière, R.; Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Roseman, L.; Trautwein, F.M.; Berkovich-Ohana, A. Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, J.; Chambers, R.; Liknaitzky, P. Combining Psychedelic and Mindfulness Interventions: Synergies to Inform Clinical Practice. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, T.; Schuyler, B.S.; Mumford, J.A.; Rosenkranz, M.A.; Lutz, A.; Davidson, R.J. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage 2018, 181, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekula, A. Assessing Altered States of Consciousness Seeking in Addiction with Prospective Adaptation of the Mystical Experiences Scale. Master’s Thesis, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK, 2020, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen, D.A.; Nordfjærn, T.; Geirdal, A.Ø. Change in psychosocial factors connected to coping after inpatient treatment for substance use disorder: A systematic review. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2019, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, D.; Smyth, R. Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Design | Participants and Tests | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| PP Single-dose 200 mcg LSD + 3 weeks inpatient psychosocial therapy Control treatment 3-week inpatient psychosocial therapy vs. 3-week inpatient psychotherapy 3 weeks total | n = 125 Chronic alcoholic patients of referring counselling centers Study group: 70 Control group: 55 Test (baseline, 6–18 m) Self-assessment | Main results 66% patients abstinent in experimental group vs. 41% in psychosocial group vs. 32% in psychotherapy only (p < 0.05) | - lack of diagnostic specificity - variable periods of follow-up - large numbers lost to follow-up - lack of clarity on how improvement/abstinence was measured - statistical significance poorly described |

| |||

| PP Single session of 300–450 mcg LSD + total of 24 h preparatory psychotherapy over 5 weeks + 1-week inpatient psychotherapy after Control treatment 4–6-week outpatient psychotherapy 4–6 weeks total | n = 74 Heroin-dependent, paroled, male, prisoners matched closely: age, race, religion, marital status, education, years of incarceration Study Group: 37 Control group: 37 Test (0, 12 m) Psychedelic experience questionnaire; Self-assessment of abstinence + Daily urine test Global adjustment rating scale (via interview with parole officer) | Main results Abstinence at 12 m: PAP 25%, control 5% (p < 0.05) Biopsychosocial outcomes 10/10 on global adjustment scale: PAP 32%, control 8% (p < 0.2) Other 12/13 patients with max global adjustment score reported achieving peak experience | - motivations for enrolling the study skewed by likely favorable parole eligibility - sociocultural differences between white therapists and predominantly black inmates/patients - global adjustment rating scale and “psychedelic experience questionnaire” not empirically validated; inconsistent dosing regimens |

| |||

| High dose PP: 2.0 mg/kg im Ketamine + single-session psychotherapy + existentially oriented psychotherapy pre/post Ketamine + inpatient stay Active Control: 0.2 mg/kg im Ketamine + single-session Ketamine psychotherapy + existentially oriented psychotherapy pre/post Ketamine + inpatient stay 3–5 days total | n = 70 Detoxified, heroin-dependent inpatients at a substance use treatment center, able to provide close affiliate for corroborating data, no significant psychological + craving differences Study Group: 35 Control Group: 35 Test (Baseline, Day 0, 3 m, 6 m, 9 m, 12 m, 18 m, 24 m) Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (ZDS); Spielberger Self-rating State-Trait Anxiety Scale of Anhedonia Syndrome (SAS); Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI); Locus of Control Scale (LCS); Color Test of Attitudes (CTA); Purpose-in-Life Test (PLT); Spirituality Changes Scale (SCS); Urine toxicology | Main results Abstinence rates: High-dose PAP 17%, active control 2% (p < 0.05) at 24 m Biopsychosocial outcomes

| - no true control group - abstinence verification procedure poorly described - high loss to follow-up by 24 m |

| |||

| Single dose PP: 2.0 mg/kg im Ketamine Multiple dose PP: 0 m, 1 m, 2 m: 2.0 mg/kg im Ketamine Other 5 h preparatory psychotherapy at 0 m +Pre-dose addiction counselling at 1 m, 2 m +1 h post-dose psychotherapy at 0 m, 1 m, 2 m | n = 53 Inpatients at a substance use treatment center, detoxified and abstinent >2 weeks, with heroin dependence for at least 1 year, no significant psychological + craving differences Single dose PP: 27 Multiple dose PP: 26 Test (Baseline, Day 0, monthly for 12 m) Physical exam; Urine toxicology; ZDS, SAS, PLT and VASC; telephone interview, self-report assessment via Timeline Follow-Back technique | Main results Abstinence rates at 12-month follow-up: multiple-dose PP 50% vs. single-dose PP 22% (p < 0.05) Biopsychosocial outcomes Significant improvements at 12-month f/u (p < 0.005) in depression; state and trait anxiety; cravings for heroin; understanding the meaning of life | - no placebo control group - no adequate blinding was feasible |

PP

Ritualistic setting overseen by indigenous shamans 4 days total | n = 12 Non-abstinent, non-treatment seeking, polysubstance using volunteers Test (Baseline, Day 1, Week 2, monthly on Month 1–6) Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS); Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale (PHLMS); Empowerment Scale (ES) Hope Scale (HS); McGill Quality of Life survey (MQL); 4-Week Substance; Use Scale (4WSUS); Semi-structured Qualitative Interview | Main results Substance use (average 4WSUS score 6 m f/u vs. baseline): Tobacco 18% reduction, alcohol 30% reduction, cocaine (p < 0.05) 60% reduction, hallucinogens 9.1% increase, opiates, cannabis and sedatives nil change. Biopsychosocial outcomes

| - small sample size - homogenous sample population - no control group - no standardization of dose - ritualistic context may have a confounding effect size - low rigor of statistical analysis - no record of any other concurrent treatments - some participants were repeat attendees |

| |||

| PP Ayahuasca brew, differing protocols | n = 14 Substance-dependent volunteers, mean age 42 years, 2 years post-Ayahuasca ceremony Test (>2 years post treatment) Unstructured interview | Main results (no statistical analysis)

Better understanding of the underlying causes of addiction; improvements in self-efficacy; transformation of consciousness to help overcome cravings; lowered psychological defense mechanisms | - small sample size - homogenous sample population - no control group - non-randomized, purposefully chosen sample - no standardization of original intervention - no statistical analysis of results |

| |||

| PP Randomized to:

Day 1–3: Inpatient achievement of abstinence 9 days total | n = 8 Non-abstinent, non-treatment seeking, cocaine-dependent volunteers Test (Baseline, Day 1, weekly on Week 1–4) University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA); Visual Analog Scale of Craving (VASC); psychiatrist interview of abstinence via Timeline Follow-Back technique; urine toxicology | Main results

Motivation to change (Day 1 Median URICA score): Low-dose Ketamine 3.6 vs. Lorazepam 0.15 (p = 0.012) | - small sample size - homogenous sample population - no placebo control group - short interval between 1st and 2nd dose is likely to confound 2nd dose results |

| PP 20–30 mg/70 kg Psilocybin at Week 5, Week 7 and optional at Week 13 + Week 1–4: Weekly CBT for smoking cessation + Week 5–15: Weekly supportive psychotherapy 15 weeks total | n = 15 Nicotine-dependent volunteers, >10 cigarettes per day, multiple unsuccessful quit attempts, seeking to quit Test (Weekly on week 0–15, 6 m): Breath Carbon Monoxide level Urine Cotinine level; self-report; States of Consciousness Questionnaire (SOCQ) | Main results Abstinence: 80% at 6 m, 67% at 12 m, 60% at >12 months (p < 0.05) Biopsychosocial outcomes

|

|

| PP 0.3 mg/kg Psilocybin at 4 weeks + 0.3–0.4 mg/kg at 8 weeks + 7 sessions of motivational interviewing + 3 preparatory sessions + 2 debriefing sessions post PP 12 weeks total | n = 10 Alcohol-dependent, concerned about their drinking, not currently in treatment, abstinent and not in withdrawal Test (Baseline, Weeks 0, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 24, 36) SCID for DSM IV Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI) Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale (AASE) Profile of Mood States (POMS) Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) procedure self-assessment of drinking Breath Alcohol Concentration (BAC) | Main results

positive mood changes, positive attitudes about the self and life, altruistic social effects, and increased spirituality; maintained at up to 12 months. | - small sample size - no control group - no biological verification of reduced use/abstinence |

| |||

| PP Single-dose Ibogaine 10 mg/kg + inpatient stay 12 days total | n = 191 102 Opiate-dependent and 89 Cocaine-dependent active users self-referred for detoxification Test (Baseline, Days 0, 5, 30) Heroin (HCQ-29) and Cocaine (CCQ-45) Craving Questionnaires Beck Depression Inventory version II (BDI-II); Profile of Moods (POMS, 2nd edition); Symptom Checklist—90 scales (SCL-90) | Main results Significant improvements in urgency of use and ability to quit (p < 0.0001) at Day 30 Biopsychosocial outcomes

|

|

| |||

| PP Single-dose Ibogaine 25–55 mg/kg + inpatient stay Other Inpatient stay: Provider 1: >1 week (n = 1) Provider 2: <4 days (n = 13) Up to 1 week total | n = 14 Opiate-dependent volunteers seeking treatment, able to provide close affiliate for corroborating data, recruited from 2 different ibogaine treatment providers Test (Baseline, Day 0, 3 m, 6 m, 9 m, 12 m) Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale (SOWS); Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI-Lite); Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDIII); urine screens | Main results

Depression scores: >50% reduction (p = 0.013) at 1 m, 80% reduction (p = 0.004) at 12 m | - small sample size - selection bias from patient sample actively seeking Ibogaine treatment - inconsistency in matching of substance use reports and biological verifications - post-treatment protocols varied between 2 providers - inconsistent dosing regimens |

| |||

| PP Single dose of 1540 mg Ibogaine + inpatient treatment Other Stabilized for 3 days pre-dose on short acting opioid 3–6 days total | n = 30 Heavy and relatively selective users of opioids, actively seeking treatment, able to provide close affiliate for corroborating data, recruited from 2 different ibogaine treatment providers Test (Baseline, Day 0, 3 m, 6 m, 9 m, 12 m) Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI-Lite); Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) | Main results

Family/social issues: >80% reduction (p < 0.001) at 12 m | - small sample size - no control group - no biological verification of self-report metrics - recent long-acting opioid use confounding consistency of withdrawal profile |

| |||

| PP Ketamine 0.71 mg/kg as IV infusion Control Midazolam 0.025 mg/kg as IV infusion Other 6-session motivational interviewing 5 weeks total | n = 40 Non-abstinent, treatment seeking, alcohol-dependent volunteers Study Group: 17 Control Group: 23 Test (Baseline, Day 1, weekly on Week 1–5, 6 months) Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment; Alcohol Abstinence Self-Efficacy Scale; Perceived Stress Scale; Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; Barrett Impulsiveness Scale; psychiatrist interview of abstinence via Timeline Follow-Back technique; urine toxicology | Main results

No significant differences in craving, withdrawal, mindfulness, impulsivity, stress sensitivity, and self-efficacy | - small sample size - homogenous sample population - no placebo control group - high rates of dropout at 6 m f/u - 6 m f/u did not follow TLFB technique - results of psychological measures not clearly reported |

| Treatment | Participants and Tests | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| TM 4-day instruction + group f/u daily/6 weeks; weekly/3 m; bimonthly until 10 m + individual sessions available + drug dependence treatment Control drug-dependence treatment (unspecified) 10 months total | n = 66 drug-dependent inmates, meditation-naive; stopped intake of illegal drugs ≥ 15 days prior Study group: 30 interested in meditation Control group 1: 20 interested in meditation Control group 2: 16 uninterested in meditation Test (baseline, 10 m) Spielberger State/Trait Anxiety Inventory | Main results TM: 2 reduced all substances, 6 ceased all drugs; 6 reduced smoking, 2 ceased smoking Biopsychosocial outcomes

| - no control group data on substance use or activities - substance abuse: unreliable in prison due to fear of repercussions - no baseline data on substance use - TM is an adjunct to a drug-dependence treatment |

| |||

| TM 4-day instruction + group f/u 2 h weekly/1 m + counselling: 4 h biweekly Control 3-month counselling Other Therapist in both groups: psychiatrist or psychologist 6 months total | n = 20 Youth Study group: 10 Control group: 10 Each group: 6 hashish only and 4 hard drug users (LSD, opiates, amphetamines); 5 drug-related convictions Test (0, 3, 6 m) behavioral observation Leisure time: 0—no time, 3—much time | Main results (all p’s < 0.05)

f/u attendance: all TMs, 7/10 controls | - small, unrepresentative sample size - vague outcome measures |

| |||

| TM Personal TM instruction, applied at various times by various teachers Control no treatment | n = 417 members of Philadelphia World Plan Centre of the International Meditation Society Study group: 264 (194 active meditators/70 no longer meditating) Control group: 153 non-meditating friends of study group members Test (3 m before treatment, post treatment) Average weekly substance use | Main results Before treatment/post treatment

| - no description of intervention procedures - low return rate of questionnaires (22.3%) - retrospective study, limited variable control |

| |||

| TM 4-day instruction, 1.5 h/day + group f/u 1 h/weekly for 3 m Qualified instructor, staff instructed on method Control individual psychotherapy + group counselling weekly/3 m 3 months total | n = 18 male war veterans, all motivated, blind to treatment type Study group: 10 Control group: 8 Test (baseline, 3 m) PTSD Figley Scale, Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Figley post-Vietnam Adjustment scale (1—most severe, 4—no problem), stress copying: audio stimulus habituation via skin resistance (stimulus GSR) |

| - small, homogenous sample size - no info on previous treatment |

| |||

| TM Routine treatment + TM: 3 prep meetings + 1 individual session + 3 group sessions + 2 × 20 min TM meditation for 20 days; f/u 1/month Certified instructors Control 1 Electromyographic biofeedback, 1 h/day + 20 min/day self-practice for 20 days Control 2 Neurotherapy, 30 min for 15 days Control 3 3-month routine treatment: AA and alcoholism counselling 18 months total | n = 118 inpatients, long history of abuse; 1-week detoxification Study group: 35 (f/u 32) Control group 1: 24 (f/u 22) Control group 2: 28 (f/u 26) Control group 3: 31 (f/u 25) Test (baseline; 1–6 m; 7–12 m; 13–18 m) Social history Questionnaire, Beta Intelligence Tests, Profile of Mood States | Main results (group effects at all time points p < 0.05) % of days at baseline/1–6 m/7–12 m/13–18 m:

TM improved from baseline (p < 0.05) on tension–anxiety, depression–dejection, anger–hostility, vigor activity, fatigue–inertia, confusion–bewilderment. Other Adherence: TM—90.2%; Control 1—88.6%; Control 2—94.8% | - biopsychosocial measure report vague |

| |||

| TM 4-day instruction 1.5 h/day, voluntary f/u Controls None 4 days total | n = 324 volunteers; 20% tried professional methods to quit Study group: 110 Control group: 214 no significant differences on demographic, smoking measures, motivation, attempts to quit Test (baseline, 20–24 m) smoking and adherence |

| - mailed-out, self-report questionnaires - non-randomized - no report on the relationship between the desire to quit and outcome - no information on TM instruction procedure or instructor |

| TM 90 min intro + 10 min interview + 1 personal + 3 group instructions; f/u: individual 30 min/week in 1st month then once/month; voluntary weekly group meetings; teachers certified by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1970s), 6 m training, >35 y experience, recertified in 2005 Control none Other participants and assessors blind to study aim and conditions 3 months total | n = 207 students, all substances used; non-sig diff on demographics and substance use; matched on ADHD and gender Study group: 93 Control group: 114 Test (baseline, 3 m) substance use inventory, Profile of Mood States (total mood disturbance scale + tension/anxiety, depression/rejection, anger/hostility) constructive Thinking Inventory | Main results

TM adherence (once/day) 65% | - smoking and drug use already low at baseline - smoking and drug use banned in restricted university environment, drinking age 21 - motivation to decrease substance use not measured/unlikely - very low adherence - possible instructor effect - measurements of preceding week only, likely obscured information (e.g., weekend binge) |

| |||

| TM Prolonged exposure OR cognitive processing therapy + TM: 5 days, 6 × 2 h individual sessions + group meetings + voluntary f/u (1st month weekly, 2–6 m monthly) Certified teachers, Maharishi Foundation Controls Prolonged exposure OR cognitive processing therapy 6 months total | n = 74 active-duty military service members with PTSD or Anxiety Disorder; inpatients, completed traumatic brain injury therapy Study group: 37 Control group: 37 matched on age, sex, diagnosis and baseline medication use Test (baseline, 1, 2, 3, 6 m) Medication: prescription refill; total mg/week; changes in symptoms (distress, interpersonal functioning, social role) from baseline (<1 decrease, >1 increase) | Main results Psychotropic medication use:

Psychological symptom severity: at 1 m, TM—0.86, controls—1.25 (p < 0.05); at 2 m, no sig diff; at 3 m, TM—0.9, controls—1.05 (p < 0.05); at 6 m, no sig diff | - participation based on completion of TM training and self-report of regular TM practice (once per day, 5 days per week) for at least 3 months following the start of training - motivation bias - symptom severity measures vague - single value for all types/strengths of meds - retrospective study, limited variable control - possible non-compliance/misuse - to match controls, charts were reviewed over long timespan, possible treatment changes |

| |||

| TM Residential treatment + TM: 4 days of 1 h intro; 1 individual + 3 group sessions; voluntary f/u weekly/12 weeks at local centers or over the phone Certified instructors Control 3–4-week integrated substance use disorder residential treatment: medically managed withdrawal, structured activities, group and individual counselling, cognitive–behavioral counselling, 12-step approach, relapse prevention 3 months total | n = 50 AUD-diagnosed inpatients, newly admitted, those that completed medically assisted withdrawal, meditation-naive, prisoners and those with severe mental conditions excluded; non-sig diff on psychological + craving measures; TM cohort vs control: drinking (20.2 vs. 25) and heavy drinking (18.6 vs. 24) days/m at baseline Study group: 26 Control group: 24 Test (baseline, 3 m) Timeline follow-back questionnaires; alcohol consumption; Addiction Severity index Lite, Perceived Stress Scale, Alcohol Urge and Craving Experience; helpfulness of the TM scale: 0—not at all, 10—extremely | Main results

| - robust nature of facility program undermines between-group effects - inpatient study—difficult to generalize - non-randomized sample - TM adherence vs. outcomes unavailable (greater adherence to recommended TM practice was significantly correlated with better outcomes across a range of measures) |

| Treatment | Participants and Tests | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (4 × 50 min, weekly) Suggestions on misconceptions about the self in relation to smoking Control (4 × 50 min, weekly) (1) Systematic relaxation + suggestions on misconceptions about the self in relation to smoking (2) no treatment 4 weeks total | n = 70 >3 years of smoking, currently > 15 cigs/day, no predominant mental illness or current psychotherapy Study group: 22 Control group 1: 19 Control group 2: 29 Test (baseline, 4 m f/u) Smoking Cessation QA; Harvard Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility | Main results

Smoking reduction at 4 weeks and 4 m (p < 0.05): Ps in upper ⅔ on hypnotic susceptibility rating—14.5% greater in hypnotherapy vs. controls (1) | - no information on nature of hypnotic suggestion - no details on hypnotic induction procedure - no information about hypnotherapist - clinical measures used not reported - minimal statistical comparison with passive control group |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (30–60 min, 2 × week) psychotherapy + HT standard trance induction + hypnotic suggestion (desensitization of drug cue) + self-hypnosis training Control (30–60 min, 2 × week), psychotherapy, individual sessions 6 m total | n = 69 Inpatients; post 6 m methadone treatment, detoxification, no psychosis/impending incarceration Study group: 35 Control group: 34 Test (baseline, 1, 6, 9 12 m) Symptomatic complaints (severity on scale 1–3); urinary analysis; methadone med logs | Main results (all p’s < 0.05)

discomfort and withdrawal symptoms stronger for controls: trouble sleeping, no appetite, nervousness, anxiety, body aches | - no details about therapist - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - study selected only those subjects who demonstrated stability and abstinence from illicit drug use before induction into the study - no details on hypnotic induction procedure |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (4 × 60 min) induction to trance state; suggestions to emphasize negative aspects of smoking Control (4 × 60 min) (1) Focused cessation: rapid cessation technique (3 × 15 min/session) (2) Attention placebo: discussion of topics of concern to the subject (3) No treatment 4 weeks total | n = 60 avg 30 cigs/day, non-sig diff on demographics and smoking rates Study group: 15 Control group 1: 15 Control group 2: 15 Control group 3: 15 Test (post treatment; 3 and 6 m f/u) Smoking QA; serum thiocyanate level | Main results (all p’s > 0.05)

| - baseline smoking questionnaire not described - no information on hypnotherapist - assessment of abstinence rates poorly described - limited results of controls |

| |||

| Hypnosis (90 min) 3 hypnotic exercises + behavioral strategies + videotape for self-practice at home; group-based Other Smoking ban was introduced at the workplace Single treatment | n = 4367 (f/u 2642) Employees, 17% previously attended structured cessation program Test (baseline, 16 m) Cessation survey | Main results Abstinence: 15% Other 71% of all smoking employees attended at least 1 session; 80% reported quitting because of smoking ban | - no control condition - hypnosis combined with introduction of smoking ban at a workplace policy - no details on the hypnosis session - no info on the hypnotherapist |

| |||

| Hypnosis (60 min) hypnosis included relaxation (deep breathing, concentration on self-efficacy phrases and being in control of situations, 40 min) + audiotape (progressive muscle relaxation, breathing, self-hypnosis induction, repetitions of positive attitude phrases, 9 min) + info on smoking risks (20 min) hypnotherapist: clinician, >15 years of hypnosis experience Single treatment | n = 452 volunteers attending American Lung Association hypnosis session; 79% attempted to quit previously Test (5–15 m post instruction) over-the-phone smoking QA | Main results

| - no control condition - 17% had previous experience with hypnotherapy; 55% rated themselves as easily hypnotized - 59% simultaneously used other strategies (including 26% nicotine replacement therapy and 6.2% oral substitutes) - paid participation (USD 40) |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (4 × 50 min) intensive therapy + self-hypnosis training audiotape records + slow deep breathing with hypnotic suggestions: ego strengthening, relapse prevention, serenity enhancement, anger and anxiety reduction Control (4 × 50 min) (1) intensive therapy + stress management program; (2) intensive therapy + transtheoretical cognitive–behavioral program; (3) intensive therapy only intensive therapy: group + individual; 5 days/week, 6 h/day, 21–28 days total | n = 261 (f/u 141) Inpatients of substance abuse rehabilitation program Study group: 41 Control group 1 + 2: 36 Control group 3: 64 Test (baseline; 2 m) Addiction Severity Index (ASI); State Self-Esteem Scale (SSES); Relapse Prevention Assessment Inventory (RAPI); hypnotizability (PCI-HAP); States of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES); hypnotic susceptibility (predicted Harvard Group Scale, pHGS) | Main results Abstinence (p > 0.05): 87% total abstinence, 9% relapse to drugs or alcohol, 4% relapse to both Biopsychosocial outcomes (all p’s < 0.05)

| - 13% dropped out, further 46% lost to follow-up - results on other conditions are not reported - interventions were not compared (only total data for abstinence reported; different psychological measures used) - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - highly homogenous sample (gender) - no information about hypnotherapist |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (8 × 90 min) Counselling (30 min) + mental imagery (60 min) + 4 × 5–10 min supportive phone calls Eye-focus induction + cessation suggestions + posthypnotic visualization of cessation benefits Hypnotherapist: clinical psychologist or physician, 40 h HT training provided by the PI Control Self-help materials + 4 × 5–10 min supportive phone calls 8 weeks total | n = 20 >10 cigs/day, keen to quit, no other substance abuse, no NR Study group: 10 Control group: 10 Test (pre/post treatment, weeks 12, 26 f/u) Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND); expired carbon monoxide (CO); self-report of last 7 days smoking | Main results

| - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - highly homogenous sample (gender, race, education) - small sample |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (60–90 min) Intro+ imagination exercise + individualized induction based on eyeball set induction (30 ss) + progressive relaxation + depth suggestions (1–4 min) + instructions for smoking cessation (4 min) + self-hypnosis intro Groups 1 and 2—individual; Group 3—group-based; Group 4—individual + 1–3 90 min f/up sessions; Group 5—individual + 1–3 90 min restricted environmental stimulation therapy; Group 6—individual, without individualized induction process Hypnotherapist: Groups 1, 3, 4, 5—experienced clinician; Groups 2, 6—intern Control Intro session (experienced clinician) 1–3 sessions | n = 307 volunteers Study group 1: 83 Study group 2: 45 Study group 3: 66 Study group 4: 20 Study group 5: 30 Study group 6: 16 Control group: 47 Test (6–30 m post instruction) Tellegen Absorption Scale; Beck Depression Scale; Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale (SHCS) | Main results Abstinence: Group 1: 28%; Group 2: 13%; Group 3: 36%; Group 4: 30%; Group 5: 47%; Group 6: 4%; control: 6%. Other

| - very small control group - paid participation (USD 76 to USD 296) - voluntary group selection |

| |||

| Hypnosis Phenomenology of Consciousness Inventory—Hypnotic Assessment Procedure (PCI-HAP) + self-hypnosis instructions: audio record of cessation info + CBT exercises + hypnotic suggestion (relaxation, visualization, and anchoring instructions) + intervention diary Single treatment | n = 11 (f/u = 7) volunteers Test (baseline, 6 weeks) Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; PCI-HAP assessment; alveolar carbon monoxide (CO) levels; hypnotizability, hypnotic expectancy; MSPSS (social support); DASS: Depression, Anxiety and Stress | Main results 1 abstinence, 2 reduced smoking, 4 unchanged Other

| - no control condition - psychological measures provided only at baseline - no statistical analysis - no control group - 4/11 did not complete the study |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (5 × 45 min) Psychotherapy + HT + self-hypnosis (15 min/day) Progressive relaxation, eye fixation, deep breathing, counting down, imagery visualization + therapeutic suggestions (visualizing successful opium cessation, control over oneself, mental and physical health, opium’s harmful effects, dislike and nausea when smelling opium) Hypnotherapist: clinician experienced in addiction cessation Control (5 × 45 min) Psychotherapy, consultation with clinical psychologist 1 m total | n = 21 completed detoxification, non-sig diff between groups (baseline characteristics), no drugs other than opium for 1 m prior to admission, completed detox for opium, no history of mental retardation/active psychosis Study group: 10 Control group: 11 Test (baseline, 6 m) Urine test; general behavioral questions (asked participant + reliable person, e.g., family member) | Main results relapse rate (p > 0.05): 40% (4/10) hypnotherapy; 73% (8/11) controls Biopsychosocial outcomes withdrawal symptoms (nr of patients reporting symptoms before/after hypnotherapy): Restlessness: 10/8, Insomnia: 8/7; Bodily pain: 5/3; Autonomic disturbance: 6/2 | - no information about hypnotherapist - no group comparison on subjective reports - incomprehensive tests: no scale (yes/no questions on withdrawal symptoms) - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - small, homogenous sample (gender) |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (100 min) Psycho-Education (40 min) + guided imagery HT (40 min) with suggestion to disconnect pleasant experiences from smoking, self-image of non-smoker, dealing with temptation and withdrawal symptoms, evoke positive commitment to cessation, assume responsibility + debriefing (20 min) + CD for home use Hypnotherapist: male hypnosis and relaxation therapist Control (100 min) Psychoeducation (40 min) + relaxation (40 min) with suggestion (the same) + debriefing (20 min) All group-based Single session | n = 223 (f/u 186) >5 cigs/day, wanting to quit, not using NR or other substances, no psychotic symptoms Study group: 116 (f/u 99) Control group: 107 (f/u 87) Test (baseline, 2 weeks & 6 m f/u) Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND); Beck Depression Inventory-V (BDI-V); Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI); 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12); Salivary cotinine levels; smoking abstinence and self-efficacy; Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal scale (MNWS) | Main results

No intervention effect or group differences on self-efficacy or adverse effects | - little information about hypnotherapist - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - anxiety and depression scores on f/u measured but not reported - de-blinding post intervention led to disappointment in controls, potentially lowering motivation |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (90 min) Trance (repetitive statements and deep breathing) + relaxation + phone counselling (5 × 15 min) + tape for self-hypnosis + (1) behavioral counselling (30 min) and nicotine replacement NR (1 m) OR (2) behavioral counselling (30 min) Suggestions: visual imagery on health, building self-worth and urge control, negative affectivity toward nicotine, dissociating pleasant experiences from smoking Hypnotherapist: certified hypnotist and a tobacco treatment specialist Control (30 min) (1) behavioral counselling (30 min) + NR (1 m) + self-help materials; (2) no treatment Single session | n = 155 (f/u 99) Inpatients with a cardiac or pulmonary illness, exclusion: terminal illness, other substance abuse, psychiatric illness, HT or NR within last 5 years Study group 1: 38 (f/u 25) Study group 2: 41 (f/u 27) Control group 1: 39 (f/u 27) Control group 2: 37 (f/u 20) Test self-report; urinary cotinine levels | Main results (all p’s > 0.05)

Non-smokers at 12 and 26 weeks-higher smoking-related self-efficacy at baseline (p < 0.05) | - motivation may be influenced by current/recent smoking-related admission - hypnotic suggestions not standardized |

| |||

| Hypnotherapy (5 × 60 min, wkly) Standard treatment + Erickson’s (permissive) hypnosis Relaxation and breathing exercises + mental picture of peaceful places + visualization of mastery over a problem (patient-specific) Hypnotherapist: Erickson’s hypnosis training, 10 y experience Control (5 × 60 min, weekly) Standard treatment + Motivational interviewing Standard treatment: 5 h group therapy 5 days/week + family therapy session + group activities (trips, walks, movies) 6 weeks total | n = 31 inpatients diagnosed with AUD Study group: 16 (f/u 13) Control group: 15 (f/u 11) Test (baseline, 1 y) MINI psychiatric interview; Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT); Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) days of abstinence; Global Severity Index (GSI) for mental distress (from Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) | Main results (all p’s > 0.05)

GSI mental distress (p > 0.05): hypnotherapy −0.75, controls −0.46 Other intention to treat model: no group differences | - hypnotherapy not a standalone treatment - comprehensive standard treatment program applies to both groups |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sekula, A.D.; Puspanathan, P.; Downey, L.; Liknaitzky, P. Producing Altered States of Consciousness, Reducing Substance Misuse: A Review of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, Transcendental Meditation and Hypnotherapy. Psychoactives 2024, 3, 137-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychoactives3020010

Sekula AD, Puspanathan P, Downey L, Liknaitzky P. Producing Altered States of Consciousness, Reducing Substance Misuse: A Review of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, Transcendental Meditation and Hypnotherapy. Psychoactives. 2024; 3(2):137-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychoactives3020010

Chicago/Turabian StyleSekula, Agnieszka D., Prashanth Puspanathan, Luke Downey, and Paul Liknaitzky. 2024. "Producing Altered States of Consciousness, Reducing Substance Misuse: A Review of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, Transcendental Meditation and Hypnotherapy" Psychoactives 3, no. 2: 137-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychoactives3020010

APA StyleSekula, A. D., Puspanathan, P., Downey, L., & Liknaitzky, P. (2024). Producing Altered States of Consciousness, Reducing Substance Misuse: A Review of Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy, Transcendental Meditation and Hypnotherapy. Psychoactives, 3(2), 137-166. https://doi.org/10.3390/psychoactives3020010