Interprofessional Supervision in Health Professions Education: Narrative Synthesis of Current Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

- (1)

- Examined clinical supervision, educational supervision, or structured supervisory practices involving two or more health professions;

- (2)

- Were conducted within healthcare, clinical training, or health professions education settings;

- (3)

- Reported empirical findings from quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies, or were systematic, scoping, or rapid reviews with an explicit focus on supervision; and

- (4)

- Addressed supervision-related outcomes, processes, or implementation factors relevant to interprofessional practice, learning, or workforce development.

- (1)

- Focused solely on single-profession supervision without an interprofessional or cross-disciplinary component;

- (2)

- Examined mentoring, coaching, or informal support activities without an explicit supervisory function;

- (3)

- Were opinion pieces, editorials, commentaries, or conference abstracts without sufficient empirical detail; or

- (4)

- Were conducted outside healthcare or health professions education contexts.

2.3. Data Extraction

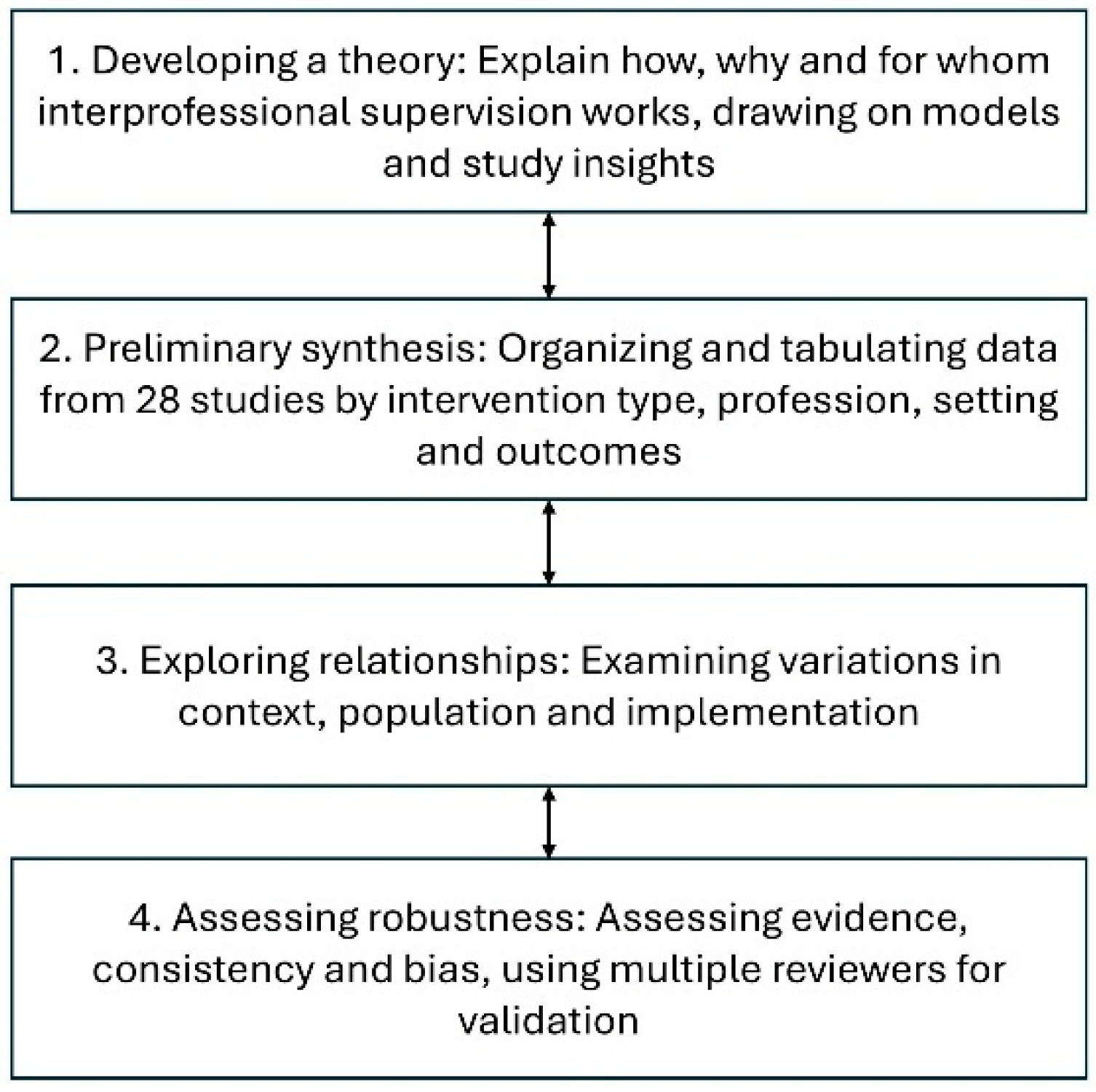

2.4. Synthesis and Assessment of Study Quality

3. Results

3.1. Interprofessional Supervision Models

3.2. Organizational and System-Level Impacts

3.3. Patient Outcomes and Quality of Care

3.4. Measurement Approaches

3.5. Implementation Factors

3.5.1. Organizational and System-Level Facilitators

3.5.2. Educational and Curricular Facilitators

3.5.3. Professional and Interprofessional Facilitators

3.5.4. Barriers to Implementation

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Evidence

4.2. Theoretical Implications

4.3. Methodological Considerations

4.4. Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DTT | Discrete Trial Teaching |

| IPE | Interprofessional Education |

| IPES | Interprofessional Education Perception Scale |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| QI | Quality Improvement |

References

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Update; Interprofessional Education Collaborative: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, B. Training for the supervision alliance attitude, skills and intention. In Fundamentals Themes In Clinical Supervision; Cutcliffe, J.R., Butterworth, T., Proctor, B., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework; Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative: Vancouver, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonsson, S.; Lundgren, T.; Andersson, G. Clinical supervision in cognitive behavior therapy improves therapists’ competence: A single-case experimental pilot study. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2020, 49, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullington, J.; Cronqvist, A. Group supervision for healthcare professionals within primary care for patients with psychosomatic health problems: A pilot intervention study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Hull, S.Z. Effectiveness of educating health care professionals in managing chronic pain patients through a supervised student inter-professional pain clinic. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, Y.; Kriss, J.; Welsh, T.M.; Bailey, J.S. Teaching supervisory skills to behavior analysts and improving therapist-delivered discrete trial teaching. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2023, 43, 256–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolansky, M.A.; Edmiston, E.A.; Vehovec, A.; Harris, A.; Singh, M.K. An interprofessional postgraduate quality improvement curriculum: Results and lessons learned over a 5-year implementation. Med. Educ. Online 2024, 29, 2408842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducat, W.; Kumar, S. A systematic review of professional supervision experiences and effects for allied health practitioners working in non-metropolitan health care settings. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2015, 8, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.; McKinstry, C.; Perrin, B. Group clinical supervision for allied health professionals. Aust. J. Rural Health 2021, 29, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, M.J.; McKinstry, C.; Perrin, B. Effectiveness of allied health clinical supervision following the implementation of an organisational framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goode, S.; Cross, D.; Hodge, G. An evaluation of a quality improvement initiative examining benefits and enablers and challenges and barriers of implementing and embedding core clinical supervision in primary care. Pract. Nurs. 2024, 35, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, H.C.; Ziniel, S.; Touloumtzis, C.; Pitts, S.; Goncalves, A.; Emans, J.; Burke, P. Case-based teaching for interprofessional postgraduate trainees in adolescent health. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; Spurr, P.; Sidebotham, M.; Fenwick, J. Describing and evaluating a foundational education/training program preparing nurses, midwives and other helping professionals as supervisors of clinical supervision using the role development model. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 42, 102671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, C.; Yamamoto, M.; Dashiell-Earp, C.; Gunawardena, D.; Gupta, R.; Simon, W. Continuity clinic practice feedback curriculum for residents: A model for ambulatory education. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2019, 11, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.R.; Dadiz, R.; Baldwin, C.D.; Alpert-Gillis, L.; Jee, S.H. Integrated behavioral health education using simulated patients for pediatric residents engaged in a primary care community of practice. Fam. Syst. Health 2022, 40, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. Clinical supervision in the bush: Is it any different? Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Lizarondo, L.; Kumar, S.; Snowdon, D. Impact of clinical supervision of health professionals on organizational outcomes: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.; Tian, E.; Kumar, S.; Lizarondo, L. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on clinical supervision practices of healthcare workers and students in healthcare settings. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3531–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, R.H.; Eade, J.; Delmage, E. The experience of clinical supervision for nurses and healthcare assistants in a secure adolescent service: Affecting service improvement. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 25, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, S.; Guerin, S. Interprofessional supervision among allied health professionals: A systematic scoping review. J. Interprof. Care 2024, 38, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miselis, H.H.; Zawacki, S.; White, S.; Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L.; Mostow, C.; Furlong, J.; Mott, K.K.; Kumar, A.; Winter, M.R.; Berklein, F.; et al. Interprofessional education in the clinical learning environment: A mixed-methods evaluation of a longitudinal experience in the primary care setting. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, S.; Baron, A.; Ansari, A.; Deamant, C.; Nelson-Becker, H.; Fitchett, G.; Levine, S. Expanding the interdisciplinary palliative medicine workforce: A longitudinal education and mentoring program for practicing clinicians. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros Perez, E.; Jimenez, E.; Yang, N.; Rocuts, A. Evaluation of anesthesiology residents’ supervision skills: A tool to assess transition towards independent practice. Cureus 2019, 11, e4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, C.; Kehoe, A.; Farook, S.F.; Illing, J. Enablers and barriers to effective clinical supervision in the workplace: A rapid evidence review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowdon, D.A.; Leggat, S.G.; Taylor, N.F. Does clinical supervision of healthcare professionals improve effectiveness of care and patient experience? A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starks, H.; Coats, H.; Paganelli, T.; Mauksch, L.; Van Schaik, E.; Lindhorst, T.; Hurd, C.; Doorenbos, A. Pilot study of an interprofessional palliative care curriculum: Course content and participant-reported learning gains. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddarth, K.H.; Jones, R.R.; O’Malley, C.W.; Paje, D.; Yamazaki, K.; Zaas, A.K.; Meade, L.B. Implementation of milestones-based assessment for a safe and effective discharge. Am. J. Med. 2016, 129, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatla, S.K.; Howard, D.; Antunes Silvestre, A.; Burnes, S.; Husson, M.; Jarus, T. Implementing a collaborative coaching intervention for professionals providing care to children and their families: An exploratory study. J. Interprof. Care 2017, 31, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, M.T.; Halvorsen, A.J.; Leasure, E.L.; Wallace, J.A.; Huber, J.M.; Mathias, T.R.; Thomas, K.G. Enhancing team development in an internal medicine resident continuity clinic. Med. Educ. Online 2024, 29, 2430570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winn, A.S.; Marcus, C.H.; Williams, K.; Smith, G.C.; Gorbounova, I.; Sectish, T.C.; Landrigan, C.P. Development, implementation, and assessment of the Intensive Clinical Orientation for Residents (ICOR) curriculum: A pilot intervention to improve intern clinical preparedness. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gough, D. Weight of evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Res. Pap. Educ. 2007, 22, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Author, Year) | Country | Study Design | Participants | Supervision/Educational Model | Format & Duration | Primary Competency Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfonsson et al., 2020 [7] | Sweden | Quantitative (single-case experimental) | 6 CBT therapists | CTS-R–guided clinical supervision | Weekly individual sessions; 5–8 weeks | CBT competence, reflective practice |

| Bullington & Cronqvist, 2018 [8] | Sweden | Qualitative intervention pilot | 6 primary care professionals | Phenomenological supervision model | Monthly group supervision; 6 months | Clinical reasoning, reflective practice |

| Cao & Hull, 2021 [9] | Australia | Quasi-experimental (pre–post) | 6 interprofessional students | Supervised interprofessional pain clinic | Weekly team-based clinical sessions; 12 weeks | Interprofessional teamwork, pain management |

| Cruz et al., 2023 [10] | USA | Experimental (multiple baseline) | 3 BCBAs and supervisees | Performance-based supervision training | Individual coaching to mastery | Supervisory skills, feedback delivery |

| Dolansky et al., 2024 [11] | USA | Quasi-experimental (pre–post) | 74 postgraduate trainees | Longitudinal interprofessional QI curriculum | Weekly didactics + clinical projects; variable by profession | Quality improvement, systems thinking |

| Ducat & Kumar, 2015 [12] | Australia | Systematic review | Allied health practitioners | Professional supervision (varied models) | Individual/group; mixed modalities | Professional support, job satisfaction |

| Gardner et al., 2021 [13] | Australia | Mixed methods | 16 allied health staff | Group clinical supervision (critical reflection) | Monthly/bimonthly group sessions | Reflective practice, peer learning |

| Gardner et al., 2022 [14] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | 125 allied health staff | Organizational supervision framework | Mostly individual supervision; ongoing | Formative, normative, restorative supervision outcomes |

| Goode et al., 2024 [15] | UK | Quantitative observational | 30 primary care staff | Core Clinical Supervision (NHS framework) | Mixed 1:1 and group; 18 months | Professional confidence, wellbeing |

| Gooding et al., 2016 [16] | USA | Mixed methods | 7 postgraduate trainees | Case-based interprofessional curriculum | Weekly sessions; 6 months | Collaboration, adolescent healthcare |

| Harvey et al., 2020 [17] | Australia | Mixed methods | 226 supervisors | Role Development Model training | 8 days over 6–9 months | Supervisory competence, reflective capacity |

| Haynes et al., 2019 [18] | USA | Quasi-experimental | 144 residents | Practice feedback curriculum | Longitudinal; 1 year | Practice-based learning, self-assessment |

| Jones et al., 2022 [19] | USA | Mixed methods | 34 pediatric residents | Simulated patient–based curriculum | Workshops + simulations | Interprofessional communication |

| Martin, 2018 [20] | Australia | Mixed methods | Health professionals (unspecified) | Clinical supervision in rural settings | Flexible, context-driven | Supervision quality, workforce support |

| Martin et al., 2020 [21] | Australia | Review protocol | Qualified health professionals | One-to-one clinical supervision | Not applicable | Organizational outcomes |

| Martin et al., 2022 [22] | Australia | Rapid review | Healthcare workers and students | Adapted supervision during COVID-19 | Virtual/in-person/hybrid | Continuity of supervision |

| McCarron et al., 2017 [23] | UK | Mixed methods | Nurses and HCAs | Organizational supervision interventions | Group and multidisciplinary supervision | Staff support, service improvement |

| McGuinness & Guerin, 2024 [24] | Ireland | Scoping review | Allied health professionals | Interprofessional supervision | Not applicable | Interprofessional supervision practices |

| Miselis et al., 2022 [25] | USA | Mixed methods | 35 trainees | Longitudinal interprofessional clinic | Weekly 4-h clinic | Team-based care competencies |

| O’Mahony et al., 2020 [26] | USA | Mixed methods | 26 clinicians | Interdisciplinary mentoring program | Hybrid; 2 years | Palliative care competencies |

| Riveros Perez et al., 2019 [27] | USA | Quasi-experimental | 37 residents | Supervision skills training | Lecture + simulation; single session | Supervisory competence |

| Rothwell et al., 2021 [28] | UK | Rapid evidence review | Mixed professions | Proctor’s supervision model | Individual/group; ongoing | Professional development, wellbeing |

| Snowdon et al., 2017 [29] | Australia | Systematic review | Healthcare professionals | Clinical supervision (varied models) | Individual/group | Clinical effectiveness, patient outcomes |

| Starks et al., 2017 [30] | USA | Mixed methods | 24 clinicians | Interprofessional palliative curriculum | 9 months; blended learning | Communication, team practice |

| Suddarth et al., 2016 [31] | USA | Quasi-experimental | 274 faculty | Milestones-based supervision tool | Workplace-based; ongoing | Assessment and feedback skills |

| Tatla et al., 2017 [32] | Canada | Mixed methods | 36 providers | Collaborative coaching intervention | 6 months | Coaching- and family-centered care |

| Wingo et al., 2024 [33] | USA | Mixed methods | 172 team members | TeamSTEPPS-based curriculum | Longitudinal outpatient blocks | Team development, patient safety |

| Winn et al., 2018 [34] | USA | Mixed methods | 48 interns | Intensive clinical orientation | 3.5-day program | Clinical preparedness |

| Study Identification | Quality Appraisal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Study Identification | Title | Relevance to Review Question | Methodological Quality | Clarity of Reporting | Risk of Bias | Justification |

| 1 | Alfonsson et al., 2020 [7] | Clinical supervision in cognitive behavior therapy improves therapists’ competence: A single-case experimental pilot study | High: demonstrates how structured supervision enhances specific therapeutic skills and therapist development, facilitating collaboration through competency growth | High clarity, appropriate methods for pilot single-case design; clear description of supervision protocol | High clarity, appropriate methods for pilot single-case design; clear description of supervision protocol | Low-moderate; randomization of baselines, blinded raters; small sample size limits generalizability | Clear rationale for standardization and focus on CTS-R competencies; aligns with gaps in supervision research |

| 2 | Bullington & Cronqvist, 2018 [8] | Group supervision for healthcare professionals within primary care for patients with psychosomatic health problems: A pilot intervention study | High: shows how clinical supervision supports interprofessional reflection, emotional processing, and shared care thinking, even when it does not lead to standardized strategies | Moderate to high: clear intervention description and analytic method, though small sample and no discipline-specific breakdown weakens generalizability | Moderate to high: clear intervention description and analytic method, though small sample and no discipline-specific breakdown weakens generalizability | Moderate: small, self-selecting sample; lack of diversity data; unclear fidelity to theoretical model; no triangulation of perspectives (e.g., patients, supervisors) | Well-grounded in challenges of treating psychosomatic cases in primary care; supervision is underutilized and this intervention fills a gap in reflective, low-cost interprofessional development |

| 3 | Cao & Hull, 2021 [9] | Effectiveness of Educating Health Care Professionals in Managing Chronic Pain Patients Through a Supervised Student Inter-professional Pain Clinic | Very high: demonstrates that supervised, structured IPE fosters team-based learning, improves communication and collaborative attitudes, and enhances student readiness for future interprofessional practice. | High: clear intervention design, validated tools, appropriate statistical tests (Wilcoxon, Kruskal–Wallis, RM ANOVA). Well-explained participant demographics and outcomes. | High: clear intervention design, validated tools, appropriate statistical tests (Wilcoxon, Kruskal–Wallis, RM ANOVA). Well-explained participant demographics and outcomes. | Moderate: No control group; possible selection bias (voluntary participation); limited generalizability beyond chronic pain and U.S. context | Strongly justified: addresses a known gap in pain education and interprofessional training. The real-world clinical setting adds relevance and feasibility. |

| 4 | Cruz et al., 2023 [10] | Teaching Supervisory Skills to Behavior Analysts and Improving Therapist-Delivered Discrete Trial Teaching | Moderate: focuses on supervision skill-building within one discipline. While not interprofessional, it strongly supports structured supervision to enhance team performance and skill transmission. Could inform supervision models in multi-disciplinary contexts. | High: clear design (multiple baseline), strong operational definitions, replication across participants, fidelity monitoring | High: clear design (multiple baseline), strong operational definitions, replication across participants, fidelity monitoring | Low to moderate: small sample size, no control group; participants from one setting; strong internal validity | Well-justified given supervision is core to ABA practice. Builds on evidence-based methods for training and feedback delivery. |

| 5 | Dolansky et al., 2024 [11] | An interprofessional postgraduate quality improvement curriculum: results and lessons learned over a 5-year implementation | This study demonstrates how a longitudinal, coached, interprofessional QI curriculum can enhance teamwork, practical learning, and collaborative care delivery. Coaches, experiential learning, and alignment with institutional goals were key to success—providing a model for supervisory practices that foster interprofessional competence and cooperation. | Moderate: appropriate for real-world educational settings (quasi-experimental), but lacks control group and formal measurement of interprofessional collaboration. | High: the article follows SQUIRE-EDU guidelines, provides detailed descriptions of curriculum, participants, outcomes, and lessons learned. | High: well-supported by existing literature and professional competency frameworks. Clear rationale for targeting interprofessional QI training. | High: well-supported by existing literature and professional competency frameworks. Clear rationale for targeting interprofessional QI training. |

| 6 | Ducat & Kumar, 2015 [12] | A systematic review of professional supervision experiences and effects for allied health practitioners working in non-metropolitan health care settings | Relevant: identifies supervision as a mechanism to support allied health professionals in collaborative, resource-limited contexts; highlights challenges in defining and structuring supervision to optimize collaboration | Moderate to Low: included studies were methodologically weak (small samples, lack of validated measures, inconsistent definitions) | High: clearly reported aims, methods, and narrative synthesis. | Moderate: limited number of included studies (n = 5), self-reported data, variable supervision models, lack of robust outcome measures or control groups | High: authors provide a clear rationale for focusing on rural allied health, citing gaps in previous reviews and workforce challenges |

| 7 | Gardner et al., 2021 [13] | Group clinical supervision for allied health professionals | High: demonstrates how structured group supervision with trained facilitators fosters peer learning and interprofessional collaboration in rural settings; supports supervision as a catalyst for team-based support. | Moderate: small sample, no control group, some bias risk acknowledged | High: well-described methods, tools, outcomes. | Moderate: small group sizes, self-reporting, 42% non-response; lead author was a facilitator in one group | High: clearly grounded in known rural supervision barriers; aligned with workforce development goals |

| 8 | Gardner et al., 2022 [14] | Effectiveness of allied health clinical supervision following the implementation of an organisational framework | High: demonstrates how organizational supervision frameworks, when implemented with interprofessional training and clear structure, can improve clinical supervision and contribute to team dynamics and collaboration | Moderate: strong design (action research), but limited by lack of true pre-post or control group | High: transparent reporting, well-documented tables, clear rationale | Moderate: self-reported data, 50% response rate, some professions under-represented; lead author involvement may introduce bias | High: clearly justified with literature and policy gaps; builds on prior internal survey and aligns with rural health workforce needs |

| 9 | Goode et al., 2024 [15] | An evaluation of a quality improvement initiative examining benefits and enablers and challenges and barriers of implementing and embedding core clinical supervision in primary care | High: demonstrates how structured, reflective clinical supervision models can enhance collaboration, professional growth, and team function in multidisciplinary primary care settings | Moderate: survey-based with low response rate and no pre-post comparison | High: well-described aims, methods, and visuals | Moderate: self-selection bias; survey conducted by trainer; limited participant diversity; small sample size (n = 30) | High: clearly linked to NHS LEAP strategy and national policy on supervision and staff wellbeing; addresses known gaps in primary care supervision literature |

| 10 | Gooding et al., 2016 [16] | Case-based teaching for interprofessional postgraduate trainees in adolescent health | High: demonstrates how structured supervision (via interprofessional faculty-led case-based sessions) fosters interprofessional collaboration and role clarity | High: clear structure, validated tools, strong mixed methods design | High: clear structure, validated tools, strong mixed methods design | Moderate: small sample, single-site, self-selection bias, high baseline scores may limit measurable gains | Methods and tools are well-justified and aligned with study objectives; limitations transparently discussed (e.g., ceiling effects, context specificity) |

| 11 | Harvey et al., 2019 [17] | Describing and evaluating a foundational education/training program preparing nurses, midwives and other helping professionals as supervisors of clinical supervision using the Role Development Model | High: the program equips professionals across disciplines with reflective supervisory skills, building confidence and interprofessional insight, though direct IPC outcomes were not assessed. | High: clear methodology, detailed theoretical foundation, and rich qualitative data | High: clear methodology, detailed theoretical foundation, and rich qualitative data | Moderate: no control group, potential self-report bias, non-standardized tools | Strong—grounded in established theories and supervisory practice literature; addresses a clear training gap |

| 12 | Haynes et al., 2019 [18] | Continuity clinic practice feedback curriculum for residents: A model for ambulatory education | Moderate: while focused on supervision of data feedback, the curriculum includes coaching, peer comparison, and teamwork, contributing to collaborative and reflective practice. However, interprofessional collaboration is not a direct focus. | High: comprehensive methods, detailed reporting of activities and outcomes | High: comprehensive methods, detailed reporting of activities and outcomes | Moderate: no control group; single-site study; surveys lacked validity evidence; low post-survey response rate | Curriculum grounded in PBLI and QI theory; EHR-linked data relevant and actionable; strong alignment with ACGME competencies |

| 13 | Jones et al., 2022 [19] | Integrated behavioral health education using simulated patients for pediatric residents engaged in a primary care community of practice | High: demonstrates clinical supervision in interprofessional learning leading to collaborative practice. | High: well-reported mixed-methods with thematic saturation and appropriate analysis. | High: well-reported mixed-methods with thematic saturation and appropriate analysis. | Moderate: no control group; self-reported outcomes | Appropriate justification of method and framework; supported by literature and qualitative rigor |

| 14 | Martin, 2018 [20] | Clinical supervision in the bush: Is it any different? | Moderate: although the study does not directly evaluate interprofessional collaboration, it highlights supervision characteristics and barriers relevant to implementing interprofessional models in rural settings. | Moderate: the abstract is clearly written with a basic description of methods and findings, but limited by the brevity of the conference format. | Moderate: Tthe abstract is clearly written with a basic description of methods and findings, but limited by the brevity of the conference format. | Moderate: lack of detailed participant data, sample size, and methodology limits robustness. | Yes: justified by the need for professional support and retention in rural/remote healthcare, where supervision resources are often lacking. |

| 15 | Martin et al., 2020 [21] | Impact of clinical supervision of health professionals on organizational outcomes: A mixed methods systematic review protocol | Moderate: while the review focuses on organizational outcomes rather than interprofessional collaboration per se, it provides important insights into how supervision infrastructure and support may indirectly enhance collaborative climates and workforce sustainability. | High: protocol is structured according to JBI methodology, includes clear inclusion criteria, defined outcomes, and robust mixed methods synthesis procedures. | High: protocol is structured according to JBI methodology, includes clear inclusion criteria, defined outcomes, and robust mixed methods synthesis procedures. | Low: strong protocol design; any risk will depend on the methodological quality of included studies. | Yes: CS is underutilized yet potentially impactful in healthcare organizations. The review addresses a critical knowledge gap related to systemic and workforce-level outcomes. |

| 16 | Martin et al., 2022 [22] | A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on clinical supervision practices of healthcare workers and students in healthcare settings | High: synthesizes evidence on clinical supervision disruptions during COVID-19 | Most studies cross-sectional; some with methodological flaws; all included for synthesis | Generally clear; includes tables and thematic synthesis | Moderate: self-report data, limited psychometric testing, supervisee-only perspectives | First rapid review examining COVID-19’s impact on supervision; timely and needed for policy response |

| 17 | McCarron et al., 2017 [23] | The experience of clinical supervision for nurses and healthcare assistants in a secure adolescent service: Affecting service improvement | Directly relevant: examines supervision implementation, experience, and improvement strategies in mental health | Service evaluation; no validated questionnaire; rigorous coding with some limitations (e.g., different coders) | Detailed reporting of procedures, findings, and statistical analysis | Moderate: low response rate, lack of validation, insider researchers, no respondent validation | Provides empirical evidence of how organizational interventions affect supervision outcomes, including for HCAs |

| 18 | McGuinness & Guerin, 2024 [24] | Interprofessional supervision among allied health professionals: A systematic scoping review | Strong methodological framework (JBI), comprehensive search strategy, and clear inclusion/exclusion criteria; limitations due to study heterogeneity Moderate—study quality varied; majority descriptive or exploratory; no quality appraisal conducted as per scoping review convention | Clear and transparent reporting of methods, charting, and findings using PRISMA-ScR | Addresses a literature gap by systematically mapping existing knowledge, definitions, outcomes, and implementation barriers of interprofessional supervision | ||

| 19 | Miselis et al., 2022 [25] | Interprofessional education in the clinical learning environment: A mixed-methods evaluation of a longitudinal experience in the primary care setting | High: demonstrates implementation and impact of structured supervision within interprofessional, practice-based learning | Strong design with validated instruments and mixed methods; self-selection bias and limited validation of RIPC acknowledged | Excellent: clear description of intervention, participants, instruments, and findings | Moderate: volunteer bias, small sample size for subgroups, unvalidated instrument (RIPC) | Demonstrates successful implementation and evaluation of interprofessional clinical supervision and training in real-world settings |

| 20 | O’Mahony bet al., 2020 [26] | Expanding the interdisciplinary palliative medicine workforce: a longitudinal education and mentoring program for practicing clinicians | High: describes a comprehensive interdisciplinary training and supervision model with practical implementation outcomes | Non-validated survey instruments; robust qualitative data; structured and detailed reporting | Very clear description of intervention, participant demographics, curriculum, and evaluation results | Moderate: self-reported data, small sample, lack of control group | Demonstrates structured, scalable interdisciplinary supervision and training with measurable outcomes and actionable insights |

| 21 | Riveros Perez et al., 2019 [27] | Evaluation of anesthesiology residents’ supervision skills: A tool to assess transition towards independent practice | Directly relevant: examines supervision training for residents transitioning to supervisory roles | Validated tools used (De Oliveira Filho supervision scale); single-site, small sample, no control group | Detailed tables and explanation of intervention, metrics, and statistical analysis | Moderate: no randomization or control group; self-reported outcomes | Addresses an important training gap in supervision skills; offers replicable intervention model |

| 22 | Rothwell et al., 2021 [28] | Enablers and barriers to effective clinical supervision in the workplace: A rapid evidence review | High: focused on supervision delivery method and contextual enablers/barriers in healthcare settings | Transparent methods, but lacks formal critical appraisal due to rapid review format. Search strategy and inclusion criteria well defined. | Clear and structured presentation of both quantitative and qualitative findings | Clear and structured presentation using narrative synthesis; themes well described. | Synthesizes cross-disciplinary evidence on supervision in real-world healthcare systems. Practical implications for supervision training and organizational implementation. “Papers were limited to Western only and the last 10 years for pragmatic reasons… a rapid review necessarily pays less attention to study design and sample sizes.” |

| 23 | Snowdon et al., 2017 [29] | Does clinical supervision of healthcare professionals improve effectiveness of care and patient experience? A systematic review | High: systematic synthesis of supervision outcomes across care dimensions | Assessed using MERSQI; mean score = 13.1; 16/17 studies scored ≥ 11 | Very clear structure following PRISMA; comprehensive data tables and methods | Moderate: many non-randomized studies and reliance on documentation | Non-randomized designs (14/17 studies); reliance on medical records; heterogeneity precluded meta-analysis |

| 24 | Starks et al., 2017 [30] | Pilot study of an interprofessional palliative care curriculum: Course content and participant-reported learning gains | High: examines interprofessional supervision, skill development, and application in real clinical settings | Well-structured; limited by reliance on self-reported outcomes; use of then-test improved retrospective baseline calibration | Very clear presentation of curriculum, methods, domains, and detailed skill-level changes | Moderate: no control group, all outcomes self-reported | Demonstrates impact of structured, longitudinal interprofessional training with replicable pedagogy |

| 25 | Suddarth et al., 2016 [31] | Implementation of milestones-based assessment for a safe and effective discharge | High: demonstrates structured supervision intervention and assessment across institutions | Moderate: faculty perceptions only; no patient or resident input; variable implementation across sites | Clear methods, tables, and defined outcomes; limited generalizability | Moderate: self-report data, limited scope of participants (faculty only) | Demonstrates scalable collaborative approach to improving supervision and assessment of discharge competence |

| 26 | Tatla et al., 2017 [32] | Implementing a collaborative coaching intervention for professionals providing care to children and their families: An exploratory study | High: focuses on interprofessional coaching and supervision for healthcare professionals in real-world settings | Moderate: participatory design with mixed methods; limited by self-report and lack of control group | Well-detailed intervention, clear results presentation, appropriate thematic analysis | Moderate: no control group, self-report bias, limited psychometric validation of coaching tool | Demonstrates promising interprofessional coaching model; suggests importance of team dynamics and organizational support |

| 27 | Wingo et al., 2024 [33] | Enhancing team development in an internal medicine resident continuity clinic | High: demonstrates impact of structured team-based supervision and education in real-world resident clinic setting | Robust design using validated tools (TDM, SAQ), though limited by some contamination and short intervention period | Very clear reporting of design, intervention, analysis, and limitations | Moderate: contamination risk, short duration, lack of patient-level change | First study evaluating ambulatory TeamSTEPPS in IM residency block schedule; relevant for educational innovation and supervision strategy |

| 28 | Winn et al., 2018 [34] | Development, implementation, and assessment of the Intensive Clinical Orientation for Residents (ICOR) curriculum: A pilot intervention to improve intern clinical preparedness | High: structured clinical supervision and orientation program directly linked to EPA performance and supervision quality | Moderate: small sample, subjective outcome measures, short-term evaluation, but well-structured and piloted intervention | Clear presentation of objectives, methods, and evaluation; well-aligned with adult learning theory | Moderate: no objective competency assessment, potential self-selection bias, unblinded evaluators | Provides a replicable and novel approach to hands-on, EPA-based intern orientation in real clinical settings |

| Model Type | Study/Example | Description | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Practice-Based Supervision Models | SSIPPC—Cao & Hull [9] | 12-week program at Mercy Pain Center with students from 6 professions; weekly clinics, didactics, communication & leadership training, role clarification, and supervised patient care. | ↑ Team skills; ↑ pain knowledge (RNPQ, KnowPain50); positive IPE attitudes; high patient satisfaction; PT students showed largest improvement; qualitative: valued side-by-side learning, expected future collaboration. |

| BU CHAMPs Clinic—Miselis et al. [25] | Weekly 4 h longitudinal sessions: didactics, huddles, patient care, debriefing, documentation; full continuum of interprofessional practice. | ↑ Interprofessional competencies (ICCAS); ↑ socialization & valuing (ISVS-21); ↑ role clarity; qualitative: patient-centered care, stronger team dynamics, safe learning environments; med students benefited most. | |

| Group Supervision Models | Phenomenological group model—Bullington & Cronqvist [8] | 6 professionals in Swedish primary care; monthly 75 min sessions × 6 months; lectures, case reflection, phenomenological application. | ↑ Understanding of psychosomatics; ↑ role identity, collaboration, confidence; ↓ isolation; relational gains > theoretical retention. |

| Critical reflection group—Gardner et al. [13] | Allied health professionals in Australia; Proctor & Inskipp typologies; 1–1.5 h monthly/bimonthly sessions with reflection and solution-focused facilitation. | 67% reported positive experiences; themes: safety, trust, peer support, efficient reflection; complemented 1:1 supervision; valuable in rural settings. | |

| Competency-Based Training Models | QI curriculum—Dolansky et al. [11] | 74 postgraduates across 5 professions; 5 years of structured didactics, QI projects, faculty mentorship. | ↑ QI knowledge (QIKAT-R, p < 0.001); 100% QI project completion; national presentations; greatest success when aligned with institutional priorities. |

| Milestones-based discharge assessment—Suddarth et al. [31] | Structured discharge observation & feedback during rounds; attendings oriented to assess competence. | ↑ Direct observation; ↑ quality feedback; ↑ faculty awareness & confidence. | |

| Skills Training Models | Supervision training protocol—Cruz et al. [10] | Behavior analysts trained in supervision skills (instruction, modeling, role-play, feedback, task analysis to mastery). | ↑ Supervisor behaviors; ↑ therapist trial teaching; gains maintained post-training; cascading supervision effects. |

| ICOR—Winn et al. [34] | 3.5-day program: inpatient tasks, workshops, feedback. | ↑ Preparedness (7.0 vs. 5.6, p = 0.0496); strong satisfaction; ↑ confidence; intensive training effective for practice readiness. | |

| Case-Based Learning Models | Interprofessional case-based curriculum—Gooding et al. [16] | 6 cases over 6 months; weekly 4 h sessions; interprofessional faculty facilitated; problem-solving, role modeling, reflection. | ↑ Clinical confidence; ↑ role clarity; ↑ communication; RIPLS/IEPS stable; deep exploration & modeling valued. |

| Mentorship & Coaching Models | Collaborative coaching—Tatla et al. [32] | Participatory action research with child/family care professionals. | ↑ Coaching skills; ↑ team cohesion & communication; limited quantitative change. |

| Palliative mentoring—O’Mahony et al. [26] | 2-year hybrid program (conferences, e-learning, observation, improvement projects). | ↑ Confidence in palliative skills; ↑ interdisciplinary collaboration; successful improvement projects. | |

| Clinical Knowledge & Skills Across Models | Multiple (Cao & Hull [9], Cruz et al. [10], Dolansky et al. [11]) | Knowledge and skills gains varied by model focus (chronic pain, QI, supervision). | SSIPPC: ↑ pain knowledge; QI: ↑ QI knowledge (QIKAT-R, p < 0.001); Skills training: ↑ supervisor behavior, ↑ therapist competence; evidence of domain-specific clinical skill improvements. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, C.; Lee, E.W.Y.; Yan, C.C.; Rajaratnam, V. Interprofessional Supervision in Health Professions Education: Narrative Synthesis of Current Evidence. Int. Med. Educ. 2026, 5, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010004

Dong C, Lee EWY, Yan CC, Rajaratnam V. Interprofessional Supervision in Health Professions Education: Narrative Synthesis of Current Evidence. International Medical Education. 2026; 5(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Chaoyan, Elizabeth Wen Yu Lee, Clement C. Yan, and Vaikunthan Rajaratnam. 2026. "Interprofessional Supervision in Health Professions Education: Narrative Synthesis of Current Evidence" International Medical Education 5, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010004

APA StyleDong, C., Lee, E. W. Y., Yan, C. C., & Rajaratnam, V. (2026). Interprofessional Supervision in Health Professions Education: Narrative Synthesis of Current Evidence. International Medical Education, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime5010004